Abstract

Background

This study was conducted to clarify the effect of the inhibiting action of inhibin on porcine granulosa cell proliferation and function, and to investigate the underlying intracellular regulatory molecular mechanisms.

Methods

Porcine granulosa cells were cultured in vitro, and were treated with an anti-inhibin alpha subunit antibody, with or without co-treatment of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in the culture medium.

Results

Treatment with anti-inhibin alpha subunit antibody led to a significant increase in estradiol (E2) secretion and cell proliferation. Anti-inhibin alpha subunit antibody worked synergistically with FSH at low concentrations (25 microg/mL) to stimulate E2 secretion, but attenuated FSH action at high concentrations (50 microg/mL). Immunoneutralization of inhibin bioactivity increased FOXL2, Smad3, and PKA phosphorylation, and mRNA expression of the transcription factors CEBP and c-FOS. The expression of genes encoding gonadotropin receptors, FSHR and LHR, and of those involved in steroidogenesis, as well as IGFs and IGFBPs, the cell cycle progression factors cyclinD1 and cyclinD2, and the anti-apoptosis and anti-atresia factors Bcl2, TIMP, and ADAMTS were upregulated following anti-inhibin alpha-subunit treatment. Treatment with anti-inhibin alpha subunit down regulated expression of the pro-apoptotic gene encoding caspase3. Although expression of the pro-angiogenesis genes FN1, FGF2, and VEGF was upregulated, expression of the angiogenesis-inhibiting factor THBS1 was downregulated following anti-inhibin alpha subunit treatment.

Conclusions

These results suggest that immunoneutralization of inhibin bioactivity, through augmentation of the activin and gonadotropin receptor signaling pathways and regulation of gene expression, permits the development of healthy and viable granulosa cells. These molecular mechanisms help to explain the enhanced ovarian follicular development observed following inhibin immunization in animal models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The hormone inhibin is a dimeric glycoprotein that is primarily secreted by the gonads and plays important roles in the regulation of reproductive activities in animals [1]. Inhibin inhibits the pituitary secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) through negative feedback regulation [2,3]. Furthermore, inhibin derived from dominant or large mature follicles is believed to inhibit the development of subordinate follicles through a paracrine effect, representing a mechanism of follicular selection. Through these central and local actions, inhibin is involved in follicular selection and determination of the ovulation rate [4]. In this regard, inhibin has been viewed as a negative regulator of ovarian follicle development [5]. This response has been exploited in inhibin-immunized animals in an attempt to neutralize the biological activities of inhibin and to stimulate ovarian follicular development. Such treatments have resulted in enhanced ovarian follicular development [6], ovulation rate [7], litter size, and embryo quantity and quality following superovulation [8-10]. The stimulation of follicular development by inhibin immunization is accompanied by enhanced secretion of estradiol (E2) [7,9,10], although its role in the elevation of pituitary FSH secretion remains unclear [11]. This suggests that immunoneutralization of inhibin bioactivity may directly stimulate follicular or granulosa cell function, apart from the stimulation induced by enhanced FSH secretion. This notion is supported by evidence of direct stimulation of E2 secretion by cultured bovine granulosa cells treated with an antibody against the inhibin α-subunit [12]. Apart from enhanced E2 secretion, the mechanism underlying the enhanced growth and development of ovarian follicles following inhibin immunization remains unknown. Therefore, this study was performed to evaluate the molecular regulation of granulosa cell function by investigating the proliferation of E2-secreting cells and the expression of key molecules involved following the treatment of cultured porcine granulosa cells with anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody.

Methods

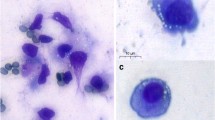

Granulosa cell culture

Ovaries of prepubertal gilts aged 165–180 days were obtained from a local slaughterhouse and transported to the laboratory in a vacuum thermos flask in sterile physiological saline at 30–37°C within 2 h of isolation. After ovaries were washed three times with sterile physiological saline at 37°C, follicular fluid and granulosa cells were aspirated from 40 medium-sized follicles, between 4 and 6 mm in diameter, that contained clear follicle fluid, by using a 10-mL syringe. The cells were then transferred to a 15-mL centrifuge tube, and 1 mL of 0.25% trypsin was added to digest cell lumps. Following incubation at 37°C for 3–5 min to disperse clumps of cells, 1 mL of 10% fetal calf serum-supplemented Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (DMEM/F12, without phenol red) was added to the tube to terminate trypsin digestion. The cells were then centrifuged at 800 g for 15 min to be precipitated and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Cell density was adjusted to 1 × 10(5) cells per well in a 96-well plate, in 200 μL of culture medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and cell survival rate was measured by the trypan blue exclusion test, which was 66 +/− 7%. The cells were incubated under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 h, and then washed with PBS to remove any unattached cells. Then, the culture medium was changed and replaced with new DMEM/F12 medium containing 2% FCS, 0.1 μM androstenedione, and a polyclonal anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody at a final concentration of 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, or 300 μg/mL. For the FSH treatment, different concentrations of FSH (0, 10, 20, or 50 ng/mL) were added to the medium, or combined with different doses of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody (0, 25, 50, or 100 μg/mL). The plates were incubated for a further 48 h under a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2 and 37°C. At the end of each incubation period, aliquots of the culture medium were collected for measuring E2 concentration. Each treatment combination was replicated in 3 culture wells in one experiment, and each experiment was repeated by 6 times.

For measurements of mRNA gene expression and phosphorylated protein levels, cells were plated at a density of 2 × 10(6) cells per well in a 6-well plate, in 2000 μL of culture medium (DMEM/F12 containing 10% FCS). Following the initial culture for 24 h and washing with PBS as described above, cells were further cultured for 48 h in the DMEM/F12 medium containing 2% FCS, 0.1 μM androstenedione, and an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody [6], at a final concentration of 0, 50, and 200 μg/mL, respectively. Then, the culture medium was carefully aspirated out, and 200 μL TRIzol (Invitrogen), for RNA extraction, or radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), for protein extraction, was added to each well. After digestion of the cells for 5 min, lysates were aspirated and stored frozen at −80°C until further analysis.

Measurement of E2 concentration

Concentrations of E2 in the culture medium were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Beijing North Institute of Biological Technology; Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The standard curve ranged from 40 to 1000 pg/mL for E2. Conditioned supernatants were diluted in FCS-free medium. Depending on the E2 concentration in the conditioned supernatants, samples were diluted 5, 40, 120, and 200 times, respectively, for treatment with each antibody concentration to ensure that the final value fell within the detection range of the standard curve. Each sample was assayed in duplicate, and the E2 concentration was calculated by multiplying the end value by the dilution factor. The assay sensitivity, range, and intra-assay coefficient of variation were 1 pg/mL, 1–1000 pg/mL, and <15%, respectively. All samples were used in a single assay.

Measurement of cell proliferation

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) is converted into yellow formazan after being reduced by succinate dehydrogenase, which is synthesized by the mitochondria of live cells. Therefore, the production of formazan is proportional to the number of live cells, which was used to represent granulosa cell proliferation in the present study. Following granulosa cell culture as described above for 24, 48, and 72 h, 10 μL of MTT solution containing 5 mg/mL thiazolyl blue MTT was added to each well of Cell Counting Kit 8 (Shanghai QCBio Science & Technologies CO., Ltd.; Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured for a further 3 h and the optical density (OD) of the yellow color was measured at 490 nm by using a Biotek EON microtiter plate reader. Each treatment was repeated by 2 duplicate wells, and then repeated by 6 independent experiments.

Western blotting

RIPA lysates from 2 culture wells of the same antibody treatment were combined and centrifuged for 15 min. The pellet was discarded and the protein concentration in the supernatant was measured by the BCA assay (Applygen Technologies, Inc.; Beijing, China). Thirty micrograms of protein-lysate from each sample was loaded and separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were then blocked using 5% (w/v) fat-free dry milk/Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at 4°C overnight, and then washed with TBS/0.05% Tween 20 three times for 20 min each. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibody against phosphorylated forms of Smad3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), PKA (Millipore), and FOXL2 (Bioss), or β-actin (13E5) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; Boston, MA) for 2 h at room temperature, and washed three times for 20 min each. The membranes were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) diluted 1:5000 in 5% (w/v) fat-free dry milk/TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times and signals were visualized using SuperSignal West-Pico kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA). The band intensity was normalized to that of β-actin. The final result was calculated as the mean of 4 independent cell cultures.

Measurements of gene expression levels

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed to quantify the mRNA expression levels of β-actin, cytochrome P450 aromatase (P450arom), cholesterol side-chain cleavage cytochrome P450 (P450scc), steroidogenic acute regulated protein (StAR), inhibin-α, inhibin-β, FSHR, LHR, fibroblast growth factor (FGF2), vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), IGFBPs, CyclinD1, CyclinD2, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (P27Kip), BCL, caspase3, A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases (TIMP), forkhead box L2 (FOXL2), CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (CEBP), and FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (FOS) in the cultured granulosa cells (Table 1). Total RNA was extracted from the TRIzol lysate, combined from 3 culture wells for each antibody treatment, and was reverse-transcribed using ReverTra Ace qPCR-RT Kit (Toyobo; Osaka, Japan) to generate template cDNA. PCRs were carried out in a 50-μL reaction volume containing SYBR Green I Master Mix (Toyobo) and 2.5 pmol relevant primers set as indicated in Table 1. An ABI PRISM_7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA) was used to detect the amplification products. Upon completion of the real-time qPCR, threshold cycle (Ct, defined as the cycle at which a statistically significant increase in the magnitude of the signal generated by PCR was first detected) values were calculated by sequence detection software SDS Version 1.2.2 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA). The levels of gene expression were expressed in the form of 2-△△Ct and normalized to expression levels of the β-actin internal housekeeping gene. Gene expression for each antibody treatment was calculated as the mean of 2 duplicate wells in a single culture, which each experiment was repeated by 6 times.

Statistical analysis

Differences between immunized and control groups, in terms of anti-inhibin α-subunit titer and concentrations of E2, were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in gene and protein expression in granulosa cells were analyzed by ANOVA. The means were compared using the least significant difference method. All values we expressed as mean +/− SEM. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software Version 8.01 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

E2 secretion

Treatment with anti-inhibin α-subunit antibodies increased E2 concentrations in conditioned supernatants from the granulosa cell culture in a dose-dependent manner. The highest E2 concentration was 7814.68 pg/mL following treatment with 200 μg/mL antibody. E2 concentration decreased further in the presence of a higher (300 μg/mL) antibody concentration (Figure 1). When both anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody and FSH were added to the culture medium, we observed an interaction between the two treatments. Without the antibody, FSH treatment led to a dose-dependent increase in E2 secretion, which plateaued at 3000 pg/mL at FSH concentrations of 20 ng/mL. The anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody appeared to attenuate the stimulatory effect induced by FSH, especially at the concentrations of 25 and 50 g/mL. But at 100 g/mL antibody concentration, inclusion of varying levels of FSH into the medium did not affect E2 concentrations, which were indifferent from that by anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment alone (Figure 2).

Estradiol concentration by cultured porcine granulosa cells in response to anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment at varying concentrations (0, 50, 100, 200, 300 μg/mL). Each value (plus SEM) represents the average of data from 6 independent culture experiments, each with 3 replicate wells. Means marked with different letters are significantly different (a-b, b-c, c-d, c-e, d-e: P < 0.01).

Estradiol concentration by cultured porcine granulosa cells in response to treatments of varying concentrations of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody (0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) and FSH (0, 10, 20, and 50 ng/mL). Each value (plus SEM) represents the average of data of 6 independent culture experiments, each with 3 replicate wells. Means marked with different letters are significantly different (a-b, b-c: P < 0.05; a-c, a-d, b-d, c-d: P < 0.01).

Cell proliferation

As an indirect measure of cellular proliferation, the results from the MTT assay revealed that treatment with an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody stimulated granulosa cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. After 24 h of culture, the antibody slightly, but not significantly, increased the formazan OD value. At 48 and 72 h, inclusion of the anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody significantly (P < 0.05) increased the formazan OD value, indicating an increased rate of cellular proliferation (Figure 3).

Proliferation (represented by the MTT OD value) of porcine granulosa cells following culture for varying times and in response to different concentrations (0, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment. Each value (plus SEM) represents data of 6 independent culture experiments, each with 3 duplicate wells. Means marked with different letters are significantly different (a-b, b-c: P < 0.05; a-c: P < 0.01).

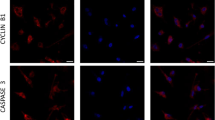

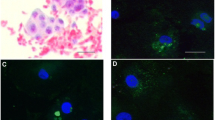

Protein phosphorylation

As shown in Figure 4, treatment of granulosa cells with an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody increased the levels of phosphorylated Smad3, PKA, and FOXL2 relative to the level of the housekeeping protein β-actin.

Expression levels of phosphorylated FOXL2, PKA, and Smad3 proteins in cultured porcine granulosa cells in response to varying concentrations (0, 50, and 200 μg/mL) of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment, normalized to β-actin expression. Each value (plus SEM) represents the average data of 4 independent culture experiments, each with 2 duplicate wells. Means marked with different letters are significantly different (a-b: P < 0.01).

Gene expression

Expression levels of the 26 genes assayed exhibited either up- or downregulation following anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment during granulosa cell culture (Figure 5). Expression of genes involved in the regulation of sex hormone secretion (FSHR, LHR, StAR, P450arom, and P450scc) was upregulated following anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment. The same was true for growth factors and related factors (IGF1, IGF2, VEGF, FGF2, IGFBP2, IGFBP5, IHNα, and IHNβ), cell proliferation- and cell cycle-regulating genes (FN1, cyclinD1, and cyclinD2), anti-apoptotic or anti-atresia genes (BCL2, TIMP, and ADAMTS), and genes involved in follicular development, as well as function-related transcription factors (FOXL2, FOS, CEBP). Downregulated genes included THBS1, the cell cycle regulatory factor p27 kip, and the gene encoding the apoptotic protein caspase-3.

mRNA expression levels of cultured porcine granulosa cells in response to varying concentrations (0, 50, and 200 μg/mL) of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment, normalized to β-actin expression. Each value (plus SEM) represents the average of data from 6 independent culture experiments, each with 3 duplicate wells. Means marked with different letters are significantly different (a-b: P < 0.05; a-c, a-d, b-c, c-d: P < 0.01).

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment on granulosa cell function to determine the mechanisms of enhanced ovarian follicular development observed following inhibin immunization. The results of this study showed that treating cultured porcine granulosa cells with an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody significantly augmented cell function in terms of E2 secretion and cell proliferation. These responses were due to significant changes in the expression patterns of genes coding for proteins associated with steroid hormone synthesis, transcription factors, and cell apoptosis, growth, and proliferation. These results suggest that treatment with an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody has widespread effects on gene expression in granulosa cells.

Inhibin is a negative regulator of ovarian follicular development, due to its inhibitory effect on pituitary gonadotropin FSH secretion [13]. Furthermore, inhibin antagonizes the stimulatory effect of activin on follicular development [5,14]. Inhibin precursors have been found to compete with FSH binding at its receptor, FSHR, which reduces FSHR signaling and subsequent FSH stimulation of granulosa cell function [15]. In animal models, immunization against inhibin has been shown to stimulate the secretion of pituitary FSH, ovarian activin, and E2, leading to enhanced follicular development and supra-normal ovulation [6,10,16-18]. Enhanced ovarian follicular function is illustrated by follicular growth and increased hormone secretion capacity. Both these activities are affected by pituitary FSH, growth factors secreted by granulosa cells, and transforming growth factor family members, including inhibin [4,19-21]. The effects of these factors are mediated by complex intracellular signal pathways that induce protein phosphorylation, leading to enhanced transcription and gene expression of key molecules in granulosa cells.

In numerous animal studies, immunization against inhibin or its α-subunit stimulated ovarian follicle development and enhanced E2 secretion, which was frequently accompanied by enhanced pituitary FSH secretion [10,22,23]. By utilizing an in vitro cell culture method, which excluded interference from pituitary-secreted FSH, we were able to elucidate the regulatory effects exerted solely by inhibin on granulosa cells. For example, immunoneutralization of inhibin by the addition of an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody into the cell culture medium led to a significant increase in E2 secretion in the present study. This result is consistent with the enhanced E2 secretion observed following the treatment of bovine granulosa cells with an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody, as well as its attenuation following treatment with inhibin A [12]. Furthermore, the present study showed that anti-inhibin α-subunit treatment led to a significant increase in E2 concentration in the culture medium, reaching 7814.68 pg/mL, which is similar to the level observed in the previous bovine study [12]. Although neither activin nor inhibin concentration was measured in the cell culture medium, it is expected that both would be synthesized and secreted by granulosa cells, as mRNA for both the inhibin-α and -β subunits was detected and upregulated by anti-inhibin α-subunit treatment. Thus, the effects of inhibin immunoneutralization should be realized by a reduction in the inhibin/activin ratio in the culture system, which should reduce the antagonizing effect induced by inhibin, and thereby enhance activin binding to the ACTRII receptor. The enhanced activin stimulation will promote E2 secretion by cultured granulosa cells. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that anti-inhibin α-subunit treatment increased Smad3 phosphorylation, an intracellular ACTR signal transduction molecule, in cultured porcine granulosa cells in the present study.

Furthermore, an interaction between the anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody and FSH was observed in the regulation of E2 secretion by granulosa cells. FSH stimulation of E2 secretion in cultured porcine granulosa cells was augmented by anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody treatment at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. When the concentration was increased (50 μg/mL), the effect of FSH was compromised, resulting in a reduction in E2 concentration to almost 80% of the maximal level. Although this result appears highly unlikely, it is nevertheless supported by previous findings showing that high (100 ng/mL) and low (3–30 ng/mL) concentrations of activin respectively prevented and enhanced FSH receptor [24] and aromatase activity [25] in cultured rat granulosa cells. Our results are also in line with the impaired development of cultured rat follicles when cells were co-stimulated with FSH and activin. The impaired FSH effect was considered to have been caused by inhibin production in the rat study [17]. Thus, under very high (100 μg/mL) concentration of anti-inhibin antibody, which readily neutralizes de novo secreted inhibin, E2 secretion was not impaired by the addition of different FSH concentrations. In the present study, we did not measure inhibin concentration in the culture medium, because the antibody could interfere with the results, making it difficult to determine the effect on E2 secretion by de novo secreted inhibin. Nevertheless, it also appears that the effect of FSH on E2 secretion is masked when a high concentration of anti-inhibin antibody is present. Animal experiments have consistently shown that enhanced ovarian follicular E2 secretion is regulated by both anti-inhibin α-subunit and FSH [10,22,23]; this same effect could be equivalent to that brought about by the intermediate, but not high, levels of antibody and FSH used in this study. Enhanced E2 secretion could also arise because of a higher number of granulosa cells. Previous findings showed no effect of inhibin treatment on the proliferation of cultured granulosa cells [26,27], which makes the role of inhibin in granulosa cell proliferation inconclusive [5]. Nevertheless, the use of an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody in the present study led to enhanced cell proliferation. This clearly suggests that inhibin may exert an inhibitory effect on granulosa cell proliferation. Such an effect could be mediated by antagonizing the effects of activin, which (alone or in combination with FSH) can exert profound promoting effects on the proliferation of cultured bovine and rat granulosa cells [21,27]. Thus, the use of an anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody in this study allowed us to overcome the disadvantage of using inhibin directly.

In this study, immunoneutralization of inhibin led to the activation of several transcription factors such as phosphorylated Smad3, PKA, and FOXL2 proteins, and mRNA expression of CEBP and c-FOS. Immunoneutralization of inhibin can increase the activin/inhibin ratio or create a state of activin ‘tone’ [5,21] in the cell culture medium. As a result, through ACTR signaling from de novo synthesized and secreted activin, the expression of phosphorylated Smad3 is elevated in cultured granulosa cells. Enhanced Smad3-mediated signaling can upregulate gene expression of FSHR and its signal pathway molecule PKA [28], and also potentiates the ovarian response to FSH stimulation [29]. Moreover, phosphorylation of PKA was enhanced in this study, although no FSH was added to the cell culture medium. Thus, enhancement of both the ACTR and FSHR signaling pathways should strengthen granulosa cell proliferation and function. Furthermore, phosphorylation of FOXL2, the earliest marker of ovarian differentiation and a key regulator of ovarian development and function [30-32], was upregulated by treatment with anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody, or increased activin ‘tone’. Thus, PKA through interaction with CEBP, together with Smad3, FOXL2, and c-FOS, modulate the expression of key genes involved in granulosa cell differentiation as well as steroidogenesis, such as StAR, P450scc, P450Cyp17, and Cyp19A1 [33-38]. For example, in the promoter region of the aromatase gene, Cyp19A1, there exist CRE-like, FOXL2, and Smad3 response elements in the proximal promoter, and c-fos AP family factor and CRE response elements in the distal promoter [34,35,39,40]. Furthermore, FOXL2 interacts with Smad3 and another transcription factor, CATA4, to regulate granulosa cell viability and apoptosis; in particular, FOXL2 inhibits cell cycle progression [41,42] and induces apoptosis, while the latter two factors suppress apoptosis [42]. PKA, via its downstream target CREB, stimulates granulosa cell proliferation [35]. It is clear that synergistic and complex regulation mediated by these transcription factors contribute to enhanced E2 secretion and cell proliferation following immunoneutralization of inhibin.

Under the regulation of these transcription factors, changes in granulosa cell functions are fulfilled by up- or downregulating the expression of relevant genes. Therefore, enhanced E2 synthesis induced by anti-inhibin α-subunit treatment was accompanied by upregulated expression of steroidogenic genes StAR, P450scc, and P450arom, as well as FSHR, LHR, IHNα, and IHNβ. Since the balance of cyclinD2 and p27 kip expression determines cell cycle progression, meiosis, and proliferation [43], the upregulation of the cell cycle progression factors cyclinD1 and cyclinD2, and the downregulation of the anti-proliferation gene p27 kip should favor cell division or proliferation, as represented by the higher MTT values of cells treated with an anti-inhibin α-subunit. Likewise, antibody treatment also upregulated the expression of IGF-I, IGF-II, and the genes encoding their binding proteins, IGFBP2 and IGFBP5. The expression of the former two genes also promotes granulosa cell proliferation and E2 secretion, while the latter two binding proteins play counter roles and could induce apoptosis of cells and follicle atresia [4,19]. Upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes (BCL2, TIMP, and ADAMTS) [44-46], and downregulation of pro-apoptotic genes (caspase-3) will further augment granulosa cell viability and cell density following treatment with anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody. This will function to further uphold E2 secretion. Some genes involved in vascularization or angiogenesis, namely, FGF2 and VEGF, were also upregulated, while THBS1 expression was downregulated by treatment with anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody. THBS1 inhibits VEGF expression in the ovary via the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 [47]. Moreover, fibronectin 1, which plays a vital role in extracellular matrix formation [48], was regulated in anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody-treated cells. These results indicate that anti-inhibin α-subunit antibody-treated granulosa cells also synthesize and secrete factors and substances that can promote follicular growth, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, while simultaneously resisting apoptosis or follicle atresia.

Conclusions

These results suggest that immunoneutralization of inhibin bioactivity, through the augmentation of activin and gonadotrophin receptor signaling pathways and regulation of gene expression, permits the development of healthy and viable granulosa cells. These molecular mechanisms help to explain the overstimulation of ovarian follicular development observed following inhibin immunization in animal models.

Abbreviations

- Cyp19A1:

-

Cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- P450arom:

-

P450 aromatase

- P450scc:

-

Cholesterol side-chain cleavage cytochrome P450

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- FSHR:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor

- LHR:

-

Luteinizing hormone receptor

- StAR:

-

Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial cell growth factor

- FGF2:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- THBS1:

-

Thrombospondin 1

- TIMP:

-

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases

- ADAMTS:

-

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs

- IGFs:

-

Insulin-like growth factors

- IGFBPs:

-

Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins

- BCL:

-

B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2

- p27kip :

-

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B

- FOS:

-

FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- FOXL2:

-

Forkhead box L2

- CEBP:

-

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

References

Rivier C, Vale W. Immunoneutralization of endogenous inhibin modifies hormone secretion and ovulation rate in the rat. Endocrinology. 1989;125:152–7.

Austin EJ, Mihm M, Evans AC, Knight PG, Ireland JL, Ireland JJ, et al. Alterations in intrafollicular regulatory factors and apoptosis during selection of follicles in the first follicular wave of the bovine estrous cycle. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:839–48.

Bleach EC, Glencross RG, Feist SA. Plasma inhibin A in heifers: relationship with follicle dynamics, gonadotropins, and steroids during the estrous cycle and after treatment with bovine follicular fluid. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:743–52.

Scaramuzzi RJ, Baird DT, Campbell BK, Driancourt MA, Dupont J, Fortune JE. Regulation of folliculogenesis and the determination of ovulation rate in ruminants. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011;23:444–67.

Knight PG, Glister C. Potential local regulatory functions of inhibins, activins and follistatin in the ovary. Reprod. 2001;121:503–12.

Li DR, Qin GS, Wei YM, Lu FH, Huang QS, Jiang HS, et al. Immunisation against inhibin enhances follicular development, oocyte maturation and superovulatory response in water buffaloes. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011;23:788–97.

Medan MS, Wang H, Watanabe G, Suzuki AK, Taya K. Immunization against endogenous inhibin increases normal oocyte/embryo production in adult mice. Endocrine. 2004;24:115–9.

Mei C, Li MY, Zhong SQ, Lei Y, Shi ZD. Enhancing embryo yield in superovulated holstein heifers by immunization against inhibin. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44:735–9.

Li C, Zhu YL, Xue JH, Zhang SL, Ma Z, Shi ZD. Immunization against inhibin enhances both embryo quantity and quality in Holstein heifers after superovulation and insemination with sex-sorted semen. Theriogenology. 2009;71:1011–7.

Liu YP, Mao XB, Wei YM, Yu JN, Li H, Chen RA, et al. Studies on enhancing embryo quantity and quality by immunization against inhibin in repeatedly superovulated Holstein heifers and the associated endocrine mechanisms. Anim Reprod Sci. 2013;142:10–8.

Drummond AE, Findlay JK, Ireland JJ. Animal models of inhibin action. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22:243–52.

Jimenez-Krassel F, Winn ME, Burns D, Ireland JL, Ireland JJ. Evidence for a negative intrafollicular role for inhibin in regulation of estradiol production by granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1876–86.

de Kretser DM, Hedger MP, Loveland KL, Phillips DJ. Inhibins, activins and follistatin in reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:529–41.

Ying SY, Becker A, Ling N, Ueno N, Guillemin R. Inhibin and beta type transforming growth factor (TGF beta) have opposite modulating effects on the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)-induced aromatase activity of cultured rat granulosa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;136:969–75.

Schneyer AL, Sluss PM, Whitcomb RW, Martin KA, Sprengel R, Crowley Jr WF. Precursors of alpha-inhibin modulate follicle-stimulating hormone receptor binding and biological activity. Endocrinology. 1991;129:1987–99.

Tohei A, Shi FX, Ozawa M, Ima K, Takahashi H, Shimohira I, et al. Dynamic changes in plasma concentrations of gonadotropins, inhibin, estradiol-17beta and progesterone in cows with ultrasound-guided follicular aspiration. J Vet Med Sci. 2001;63:45–50.

Cossigny DA, Findlay JK, Drummond AE. The effects of FSH and activin A on follicle development in vitro. Reprod. 2012;143:221–9.

Drummond AE, Dyson M, Le MT, Ethier JF, Findlay JK. Ovarian follicle populations of the rat express TGF-beta signalling pathways. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:53–7.

Monget P, Fabre S, Mulsant P, Lecerf F, Elsen JM, Mazerbourg S, et al. Regulation of ovarian folliculogenesis by IGF and BMP system in domestic animals. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2002;23:139–54.

Knight PG, Glister C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development. Reprod. 2006;132:191–206.

Knight PG, Satchell L, Glister C. Intra-ovarian roles of activins and inhibins. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;359:53–65.

Sasaki K, Medan MS, Watanabe G, Sharawy S, Taya K. Immunization of goats against inhibin increased follicular development and ovulation rate. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52:543–50.

Ishigame H, Medan MS, Watanabe G, Shi Z, Kishi H, Arai KY, et al. A new alternative method for superovulation using passive immunization against inhibin in adult rats. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:236–43.

Xiao S, Robertson DM, Findlay JK. Effects of activin and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-suppressing protein/follistatin on FSH receptors and differentiation of cultured rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1009–16.

Xiao S, Findlay JK, Robertson DM. The effect of bovine activin and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) suppressing protein/follistatin on FSH-induced differentiation of rat granulosa cells in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1990;69:1–8.

Rilianawati, Rahman NA, Huhtaniemi I. Hormonal regulation of proliferation of granulosa and Leydig cell lines derived from gonadal tumors of transgenic mice expressing the inhibin-alpha subunit promoter/simian virus 40 T-antigen fusion gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;149:9–17.

Miró F, Hillier SG. Modulation of granulosa cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and differentiation by activin. Endocrinology. 1996;137:464–8.

Li Y, Jin Y, Liu Y, Shen C, Dong J, Xu J. Smad2/3 regulates the diverse functions of rat granulosa cells relating to the FSHR/PKA signaling pathway. Reprod. 2013;146:169–79.

Gong X, McGee EA. Smad3 is required for normal follicular follicle-stimulating hormone responsiveness in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:730–8.

Uhlenhaut NH, Jakob S, Anlag K, Eisenberger T, Sekido R, Kress J. Somatic sex reprogramming of adult ovaries to testes by FOXL2 ablation. Cell. 2009;139:1130–42.

Schmidt D, Ovitt CE, Anlag K, Fehsenfeld S, Gredsted L, Treier AC. The murine winged-helix transcription factor Foxl2 is required for granulosa cell differentiation and ovary maintenance. Development. 2004;131:933–42.

Blount AL, Schmidt K, Justice NJ, Vale WW, Fischer WH, Bilezikjian LM. FoxL2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate follistatin gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7631–45.

Delidow BC, White BA, Peluso JJ. Gonadotropin induction of c-fos and c-myc expression and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1990;126:2302–6.

Delidow BC, Lynch JP, White BA, Peluso JJ. Regulation of proto-oncogene expression and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in granulosa cells of perifused immature rat ovaries. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:428–35.

Sharma SC, Richards JS. Regulation of AP1 (Jun/Fos) factor expression and activation in ovarian granulosa cell, Relation of JunD and Fra2 to terminal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33718–28.

Pannetier M, Fabre S, Batista F, Kocer A, Renault L, Jolivet G, et al. FOXL2 activates P450 aromatase gene transcription: towards a better characterization of the early steps of mammalian ovarian development. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36:399–413.

Fleming NI, Knower KC, Lazarus KA, Fuller PJ, Simpson ER, Clyne CD. Aromatase is a direct target of FOXL2: C134W in granulosa cell tumors via a single highly conserved binding site in the ovarian specific promoter. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14389.

Pisarska MD, Barlow G, Kuo FT. Minireview: roles of the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 in granulosa cell biology and pathology. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1199–208.

Sahmi F, Nicola ES, Zamberlam GO, Gonçalves PD, Vanselow J, Price CA. Factors regulating the bovine, caprine, rat and human ovarian aromatase promoters in a bovine granulosa cell model. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2014;200:10–7.

Liang B, Wei DL, Cheng YN, Yuan HJ, Lin J, Cui XZ, et al. Restraint stress impairs oocyte developmental potential in mice: role of CRH-induced apoptosis of ovarian cells. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:64.

Benayoun BA, Caburet S, Veitia RA. Forkhead transcription factors: key players in health and disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:224–32.

Anttonen M, Pihlajoki M, Andersson N, Georges A, L’hôte D, Vattulainen S, et al. FOXL2, GATA4, and Smad3 co-operatively modulate gene expression, cell viability and apoptosis in ovarian granulosa cell tumor cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85545.

Robker RL, Richards JS. Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: a coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:924–40.

Jiang JY, Cheung CK, Wang Y, Tsang BK. Regulation of cell death and cell survival gene expression during ovarian follicular development and atresia. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d222–37.

Shozu M, Minami N, Yokoyama H, Inoue M, Kurihara H, Matsushima K, et al. ADAMTS-1 is involved in normal follicular development, ovulatory process and organization of the medullary vascular network in the ovary. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:343–55.

Goldman S, Dirnfeld M, Abramovici H, Kraiem Z. Triiodothyronine and follicle-stimulating hormone, alone and additively together, stimulate production of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in cultured human luteinized granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1869–73.

Greenaway J, Lawler J, Moorehead R, Bornstein P, Lamarre J, Petrik J. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits VEGF levels in the ovary directly by binding and internalization via the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1). J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:807–18.

Dias FC, Khan MI, Sirard MA, Adams GP, Singh J. Differential gene expression of granulosa cells after ovarian superstimulation in beef cattle. Reproduction. 2013;146:181–91.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31402080), Fund for Independent Innovation of Agricultural Sciences in Jiangsu Province (CX(11)4074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LC and ZS designed the study. LC, HL, AS, and JY carried out the experimental work. ZC performed the data analysis and SY prepared the figures. LC, AT, and ZS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, L., Sun, A., Li, H. et al. Molecular mechanisms of enhancing porcine granulosa cell proliferation and function by treatment in vitro with anti-inhibin alpha subunit antibody. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 13, 26 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0022-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0022-3