Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are among the most common causes of death worldwide, including in Iran. Considering the adverse effects of CVDs on physical and psychosocial health; this study aims to investigate the association between experience of CVDs and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adult participants of the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS).

Methods

The participants of this cross-sectional study were 7009 adults (≥ 20 years) who participated in the TLGS during 2014–2017. Demographic information and HRQoL data was collected through validated questionnaires by trained interviewers. HRQoL was assessed by the Iranian version of the SF-12 questionnaire. Data was analyzed using the SPSS software.

Results

The mean age of participants was 46.8 ± 14.6 years and 46.1% of them were men. A total of 9.0% of men and 4.4% of women had CVDs. In men, the mean physical HRQoL summary score was significantly lower in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs (46.6 ± 0.8 vs. 48.5 ± 0.7, p > 0.001). In women, the mean mental HRQoL summary scores was significantly lower in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs (42.8 ± 1.0 vs. 45.2 ± 0.5, p = 0.009). In adjusted models, men with CVDs were more likely to report poor physical HRQoL compared to men without CVDs (OR(95%CI): 1.93(1.32–2.84), p = 0.001); whereas for women, the chance of reporting poor mental HRQoL was 68% higher in those with CVDs than those without CVDs (OR(95%CI): 1.68(1.11–2.54), p = 0.015).

Conclusion

The findings of the current study indicate poorer HRQoL in those who experienced CVDs compared to their healthy counterparts with a sex specific pattern. While for men, CVDs were associated with more significant impairment in the physical dimension of HRQoL, women experienced a similar impairment in the mental dimension of HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are among the most common causes of deteriorating health and death worldwide. In 2015, a total of 17.9 million deaths and 347.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in the world were owing to CVDs [1, 2]. It is estimated that by 2030, about 30.5% (more than 23 million) of all global deaths will be due to CVDs [3]. While there is a declining trend in the mortality rates of CVDs in high-income countries, about half of global CVD mortality occurred in low and middle-income countries, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean countries [2]. Similarly, in Iran, the most common causes of death have shifted from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in recent decades [4]. Based on existing evidence, Iran was found to have some of the highest prevalence of CVDs [5]. In addition to the high prevalence of CVDs and their economic burden on families and the healthcare system [6], their related outcomes such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) and coronary artery disease (CAD) can lead to fatal and non-fatal complications. Although therapeutic advances have contributed to a reduction in the mortality rate of cardiovascular outcomes, many patients of CVDs still experience other complications throughout their lives, such as stress, anxiety, fatigue and pain, sleep disturbances, shortness of breath and dyspnea [7]. In more serious cases, complications can include heart failure, the possibility of recurrent MI and sudden death [8,9,10,11,12,13]. These complications have important consequences on individuals’ mental and physical health, namely, their health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

HRQoL is a multidimensional concept that involves subjective evaluations of physical, mental, and social domains of one’s health [14]. Improving HRQoL is the ultimate goal of all health-related interventions [15]. In recent decades, the increasing proportion of individuals suffering from NCDs has been accompanied by greater interest in evaluating and improving the quality of life in individuals with these conditions [16]. In this regard, many studies found negative associations between cardiovascular outcomes and physical and mental dimensions of HRQoL [9, 17, 18]. Several factors influenced the amount of impairment such as individual’s age, employment, depression and anxiety, the duration of the disease, severity of angina, inadequate social support, complications of therapies and the experience of serious consequences such as heart failure [19,20,21,22].

Although the association between CVDs and HRQoL has been well documented in previous studies around the world [9, 17,18,19,20, 22,23,24,25], most of these studies did not explicitly consider sex differences [9, 17,18,19,20, 22] with only three studies conducting sex-specific analyses [23,24,25]. The association between CVDs and HRQoL has also been investigated in previous studies conducted in Tehran [26,27,28] and other cities of Iran [29,30,31,32,33]. However, most of the previous studies have only focused on a specific population of people with CVDs such as those who experienced either heart failure, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease or had undergone a coronary artery bypass graft [9, 13, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 34]. There is a lack of sex-specific evidence comparing HRQoL in a general population of adults with and without CVDs incidence. Furthermore, the studies previously conducted in Tehran had small sample sizes, and only one study addressed sex differences [26]. Due to limited evidence exploring this association in an Iranian population, the current study has two aims: first, to investigate the association between CVDs and the HRQoL in a large sample of Tehranian adults who participated in a cohort of the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS); and second, to explore any sex-specific differences in the association between CVDs and HRQoL. We hypothesized that participants with CVDs will demonstrate a poorer HRQoL compared to their healthy counterparts, which would follow a sex specific pattern.

Methods

Study design and participants

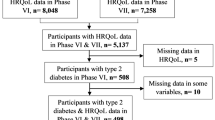

This cross sectional study was conducted within the framework of the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS), which is a community-based study that begun in 1999 and continued for 20 years. The main objectives of the TLGS were to identify risk factors of non-communicable diseases and factors associated with preventing them. A total of 15,005 individuals aged ≥ 3 years who were residence of district No.13 of Tehran, were selected and participated in the TLGS. Further details regarding rational and design of the TLGS have been published previously [35, 36]. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences (RIES) of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and all participants provided written informed consent. For the current analysis, data from all adults (≥ 20 years) who had participated in the 6th phase of the TLGS (2014–2017) and had complete information on HRQoL and CVDs incident were considered. Of 7939 individuals aged ≥ 20 years with complete HRQoL data who participated in the 6th phase of the TLGS, 930 participants were excluded due to having missing information on confounding variables; finally, data from 7009 eligible participants was analyzed. According to the results of a similar previous study [23], the minimum required sample size to compare the physical and mental HRQoL scores between the two groups of participants with and without CVDs estimated to be 907 people. Considering estimated sample size, the 7009 eligible particpants of the current study is sufficient.

Measurements and instruments

Participants' weights were measured and recorded with minimal clothing, without shoes, using a digital scale with an accuracy of 0.1 kg. Height measurement was performed by a tape in a standing position, without shoes and while the shoulders were in a normal position. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using related formula as participant’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Using BMI, participants were stratified into three weight status: (1) Normal weight: BMI < 25 kg/m2, (2) Overweight: BMI of 25 to < 30 kg/m2, and (3) Obese: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Data on demographic information, physical activity, and HRQoL were collected using valid questionnaires and through interviews. Demographic information included age, sex (male/female), marital status (Single/Divorced/Widowed/Married), level of education (Primary was defined as having education less than high school diploma/Secondary was defined as earning high school diploma/Higher was defined as earning any academic degree), and employment status (Unemployed/Student/Housewife/Unemployed, but had other sources of income/Employed) of participants. Physical activity was evaluated by the Persian version of the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ). Based on the available evidence, the Persian version of MAQ has acceptable validity and reliability [37]. In this questionnaire, physical activity was assessed through the number of times and the duration of time that the individual partakes in physical activity in a typical week. Level of physical activity was calculated using metabolic equivalents (MET) minutes/week, and the level of participants’ physical activity was grouped into either low (MET < 600 min/week), moderate (600 ≤ MET < 3000 min/week) or high activity (MET ≥ 3000 min/week) [38].

HRQoL was assessed by the SF-12 questionnaire. The questionnaire assesses health status using eight subscales including physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role emotional, and mental health. The range of scores for each scale is from zero to 100, with zero indicating the worst and 100 indicating the best position on each subscale. The psychometric characteristics of this questionnaire have been studied in the Iranian adult population with favorable validity and reliability [39].

Hypertension (HTN) was defined as SBP and/or DBP more than 140 and 90 mm/Hg, respectively, based on joint national committee criteria [40]; Type 2 diabetes was defined as fasting blood sugar FBS ≥ 126 mg/dl or 2-h post-load glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl or taking medication for diagnosed diabetes [41]; chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as structural or functional kidney damage or GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 present for more than three months according to the Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines [42]. History of cancer includes those with any report of cancer during their life.

In the current study, CVD was defined as any measures of CHD events in recent 18 years plus stroke or cerebrovascular events. CHD events are defined as cases of (1) definite myocardial infarction diagnosed by ECG and biomarkers, (2) probable myocardial infarction (positive ECG findings plus cardiac symptoms or signs but biomarkers showing negative or equivocal results), (3) unstable angina pectoris (new cardiac symptoms or changing symptom patterns and positive ECG findings with normal biomarkers), (4) angiographic‐proven CHD, and (5) CHD death; these are comparable with ICD 10 ruric I20-I25. Stroke was defined as a new neurological deficit that lasts more than 24 h (ICD 10 rubric I60-I69). Details of the definitions and analysis of CVD outcome data have been described before [43].

Statistical analysis

The distribution of continues variables was checked graphically. For all variables, the distribution diagram was drawn and compared with the normal distribution diagram. Normal continuous variables were expressed as mean ± sd, while medians (Q1–Q3) were reported for skewed variables. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Distribution of variables among groups was compared using independent samples T-test, Mann–Whitney and Chi-square test as appropriate. The HRQoL scores were compared between study participants with and without CVDs using analysis of covariance, for men and women separately. For assessing the association between HRQoL and CVDs status (absent vs. present), unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses were used. Poor HRQoL was defined as the first tertile of physical component summary (PCS) or mental component summary (MCS). The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, separately for men and women. All variables which were significantly different between the study participants with and without CVDs were adjusted. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 22 software for Windows (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The mean age of participants was 46.8 ± 14.6 years and 46.1% of them were men. A total of 457 (6.5%) of participants had CVDs. Descriptive statistics of study participants are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in the distribution of marital status, level of education, job status, levels of physical activity and smoking status between men and women. Lower percentage of women (27.6%) had low levels of physical activity compared to men (37.5%); however, higher percentages of men (23.9%) had high levels of physical activity compared to women (12.2%). In terms of smoking, a significantly higher percentage of men were smokers compared to women (42.1% vs. 5.4%, respectively). In terms of cardiovascular risk factors, women had significantly higher mean body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol, and high-density lipoproteins (HDL) compared to men (p < 0.001). On the other hand, men had significantly higher fasting blood sugar, triglycerides, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure than women. The distribution of weight status in men and women was also significantly different, with a higher prevalence of overweight in men and higher prevalence of obesity in women. Hypertension and CVDs were significantly higher in men than in women, while chronic kidney diseases were significantly higher in women than men.

Table 2 shows the mean scores of HRQoL in men and women. In all subscales, men had significantly higher scores compared to women. Similarly, men had significantly higher physical and mental summary scores compared to women.

Descriptive statistics of participants based on incident of CVDs are presented in Table 3. As it is indicated, except for smoking and BMI in men and history of cancer in women, all other variables were significantly different in those with and without CVDs outcomes. Therefore, these variables were adjusted in all analyses in Table 4 and in all regression models.

Comparison of HRQoL scores between groups of participants with and without CVDs are indicated in Table 4. All subscale scores of HRQoL were significantly lower in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs, except for bodily pain, social function and mental health subscales in men and physical function and bodily pain subscales in women. The PCS in men and MCS in women were significantly lower in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs.

Table 5 reports adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of poor physical and mental HRQoL for men and women with and without CVDs. In men, the chances of reporting poor physical HRQoL were significantly higher in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs in both unadjusted (OR (95%CI): 4.27 (3.02–6.04), p < 0.001) and adjusted models (OR (95%CI):1.93 (1.32–2.84), p = 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the chances of reporting poor mental HRQoL in men based on CVDs incidence, in both unadjusted (OR (95%CI): 0.76 (0.57-1.02), p=0.068) and adjusted models (OR (95%CI): 1.21 (0.87-1.68), p=0.270). On the other hand, in unadjusted models in women, the chances of reporting poor HRQoL were significantly higher in those with CVDs compared to those without CVDs in both physical (OR (95%CI): 3.54 (2.31–5.44), p < 0.001) and mental (OR (95%CI): 1.49(1.01–2.20), p = 0.043) aspects of HRQoL; however, after adjusting for confounding variables, only the chance of reporting poor mental HRQoL was significantly higher in women with CVDs compared to those without CVDs (OR (95%CI): 1.68 (1.11–2.54), p = 0.015).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the association between CVDs and HRQoL in Tehranian men and women who participated in the TLGS. The findings indicate that HRQoL scores were significantly lower in participants with CVDs incident compared to those without CVDs. In addition, a sex-specific pattern was observed for the association between CVDs and HRQoL. While the impairment of HRQoL scores was observed in mental dimensions of HRQoL in women; in men, this impairment was more pronounced in physical dimension of HRQoL.

According to the findings of the current study, HRQoL scores were significantly lower in those with history of CVDs compared to those without history of CVDs. Consistent with our findings, several studies in different countries reported impairments in HRQoL in patients who experienced CVD outcomes compared to their healthy counterparts [9, 12, 23, 25, 44, 45]. Similarly, findings of a study conducted in Tehran, Iran, indicated HRQoL scores in all physical and mental subscales were significantly lower in men and women who suffered from MI compared to healthy individuals, with physical subscales more impaired than mental ones [46]. Experiencing CVDs is often accompanied with several health consequences such as limitations in physical function, physical disabilities, decreased social interactions, psychological distress such as anxiety and stress, decreased vitality, early retirement due to inability to work, pain and fatigue, shortness of breath, and sleep disturbances; all of which can negatively impact various aspects of HRQoL [13, 47,48,49].

In the current study, a sex specific pattern was observed in the association between CVDs and HRQoL. In terms of HRQoL subscale scores, impairment of HRQoL in men with CVDs was more prominent in physical subscales; while in women with CVDs, lower HRQoL scores were observed in all mental subscales and to less extent in physical subscales compared to their counterparts without CVDs. There were greater impairments in HRQoL in women compared to men. One possibility for this sex difference may be due to lower compatibility with disease and slower recovery from illnesses in women in comparison to men, ultimately leading to more impairments in HRQoL [50, 51]. Another explanation for lower HRQoL scores could be related to factors such as age, psychosocial characteristics, and baseline health-related quality of life scores which have been found to be important predictors of HRQoL in CVD survivors [22]. Existing evidence indicate that women develop CVDs in older age due to the cardioprotective effect of estrogen in their reproductive stage of life; moreover, they suffer from depression more often than men, and had lower HRQoL scores compared to their male counterparts [52, 53]. Furthermore, another study found that social support is a significant determinant of HRQoL in female cardiac patients specifically in the mental dimension of HRQoL [54]. In the TLGS general population, perceived social support from family was significantly lower in women compared to men [55]. If social support is a significant determinant of HRQoL, it makes sense that women in this study experienced lower HRQoL than men, who perceived greater social support from family in their lives. A male dominant society as well as more exposure to support services in terms of social and physical activities may provide another explanation for less impairment of mental HRQoL in men compared to women [56].

Furthermore, in the current study, the chances of reporting poor physical HRQoL in men and poor mental HRQoL in women were significantly higher in those with CVDs compared to their counterparts. Related existing evidence has indicated that mood disorders, psychosomatic and psychological symptoms have been reported more in women with cardiovascular outcomes [57] compared to men, which may exacerbate the mental dimension of HRQoL in women. Despite the higher prevalence of myocardial infarction in men, women appear to have a similar or slightly higher prevalence of stable angina [58]. Studies have shown that women are more likely to have non-obstructive coronary artery disease, whereas men have more obstructive coronary artery disease and multivessel involvement in angiographic studies than women in the population referred with acute coronary syndrome [59, 60]. These findings justify the reduction of invasive therapeutic interventions in women and the lower risk of developing refractory angina and rehospitalization for unstable angina and ultimately improving their prognosis [53, 61]. On the other hand, following the higher prevalence of MI in men, they are more likely to have HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction). But regardless of its type either HFpEF (Heart failaure with preserved ejection fraction) or HFrEF (Heart failaure with reduced ejection fraction), women showed to have a better therapeutic response, maybe because compensatory responses at the cellular or molecular level appear to be more effective in women than in men [59, 62] which may contribute to the lower score of physical HRQoL in men. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is strongly associated with CVDs, which is more prevalent in men compared to women [63, 64]. Considering the impairment of the PCS in the presence of comorbidities [65]; the COPD may be another factor that contributed to the experiencing less physical function and more physical limitations in male participants of the current study with CVDs compared to their female counterparts.

Of the strengths of this study is using precise detections of CVD outcomes which allows for more accurate findings and interpretations. In addition, the use of the SF-12 questionnaire, one of the most common and popular tools for assessing HRQoL in general populations, make the findings of this study more directly comparable to those of other countries that use the same questionnaire. This study also has limitations related to its generalizability and design. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes causal inferences in the relationship between CVDs and HRQoL. Second, the participants of this study were all residents of Tehran, a large urban city; hence, the findings cannot be generalized to broader rural or sub-urban communities in Iran. In addition, in the current study, because the estimated effect sizes of the group-based comparisons were small, the significant differences observed in HRQoL scores between those with and without CVD outcomes may be due to the large sample size and should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, data of income was not collected in the current study. Since, income may influence the HRQoL of particpants; therefore, in future studies, it is recommended to collect participants’ income and include it in future analysis. Lastly, the SF-12 assesses general health status and may not be as responsive as a disease-specific instrument for CVDs. However, as a generic measurement, it allows for comparisons of HRQoL impairments across a range of clinical conditions, and healthy individuals. Considering coincidence of CVDs with other diseases, i.e., diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney diseases; we have just adjusted effects of these conditions in our analysis. However, it would be valuable to make comparisons between CVDs and mentioned conditions in future studies.

Conclusions

Findings of the current study indicate a significant association between CVDs and HRQoL with a sex specific pattern. In men, CVDs are associated with an impairment in the physical dimension of HRQoL, while in women, of the association was evident for mental dimensions of HRQoL. These findings can help to better plan and design interventions and the distribution of health care resources to improve HRQoL in people with CVDs incidence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kassebaum NJ, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown J, Carter A, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1603–58.

Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25.

World H, Organization. About cardiovascular diseases [cited 2020 30 Aug.]. Available from: https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/about_cvd/en/.

Danaei G, Farzadfar F, Kelishadi R, Rashidian A, Rouhani OM, Ahmadnia S, et al. Iran in transition. The Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1984–2005.

Talaei M, Sarrafzadegan N, Sadeghi M, Oveisgharan S, Marshall T, Thomas GN, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular diseases in an Iranian population: the Isfahan Cohort Study. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(3):138–44.

Mensah GA, Brown DW. An overview of cardiovascular disease burden in the United States. Health Aff (Proj Hope). 2007;26(1):38–48.

Jabir NR, Nasir Siddiqui A, Kandy Firoz C, Md Ashraf G, Kashif Zaidi S, Shahnawaz Khan M, et al. Current updates on therapeutic advances in the management of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(5):566–71.

Guidry UC, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Murabito JM, Levy D. Temporal trends in event rates after Q-wave myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;100(20):2054–9.

Brown N, Melville M, Gray D, Young T, Munro J, Skene AM, et al. Quality of life four years after acute myocardial infarction: short form 36 scores compared with a normal population. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 1999;81(4):352–8.

Solomon SD, Zelenkofske S, McMurray JJ, Finn PV, Velazquez E, Ertl G, et al. Sudden death in patients with myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, or both. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(25):2581–8.

Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, Plomondon ME, Sales AE, Grunwald GK, Every NR, et al. History of depression, angina, and quality of life after acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2003;145(3):493–9.

Mommersteeg PM, Arts L, Zijlstra W, Widdershoven JW, Aarnoudse W, Denollet J. Impaired health status, psychological distress, and personality in women and men with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: sex and gender differences: the TWIST (Tweesteden Mild Stenosis) study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(2):e003387.

Rodriguez KL, Appelt CJ, Switzer GE, Sonel AF, Arnold RM. “They diagnosed bad heart”: a qualitative exploration of patients’ knowledge about and experiences with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37(4):257–65.

Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–9.

Tengland P-A. The goals of health work: quality of life, health and welfare. Med Health Care Philos. 2006;9(2):155–67.

Megari K. Quality of life in chronic disease patients. Health Psychol Res. 2013;1(3):e27.

Crichton SL, Bray BD, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Patient outcomes up to 15 years after stroke: survival, disability, quality of life, cognition and mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1091–8.

Lewis EF, Li Y, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Weinfurt KP, Velazquez EJ, et al. Impact of cardiovascular events on change in quality of life and utilities in patients after myocardial infarction: a VALIANT study (valsartan in acute myocardial infarction). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(2):159–65.

Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, Plomondon ME, O’Brien MM, Spertus JA, Every NR, et al. Predictors of quality of life following acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(7):781–4.

Hawkes AL, Patrao TA, Ware R, Atherton JJ, Taylor CB, Oldenburg BF. Predictors of physical and mental health-related quality of life outcomes among myocardial infarction patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13(1):69.

Bengtsson MH, Hans Wedel I. Age and angina as predictors of quality of life after myocardial infarction. A prospective comparative study. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2001;35(4):252–8.

Beck CA, Joseph L, Belisle P, Pilote L. Predictors of quality of life 6 months and 1 year after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2001;142(2):271–9.

Xie J, Wu EQ, Zheng Z-J, Sullivan PW, Zhan L, Labarthe DR. Patient-reported health status in coronary heart disease in the United States: age, sex, racial, and ethnic differences. Circulation. 2008;118(5):491–7.

Brink E, Grankvist G, Karlson BW, Hallberg LR-M. Health-related quality of life in women and men one year after acute myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):749–57.

Pettersen KI, Reikvam A, Rollag A, Stavem K. Understanding sex differences in health-related quality of life following myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130(3):449–56.

Hatmi ZN, Shaterian M, Kazemi MA. Quality of life in patients hospitalized with heart failure: a novel two questionnaire study. Acta Med Iran. 2007;45(6):493–500.

Taghipour H, Naseri M, Safiarian R, Dadjoo Y, Pishgoo B, Mohebbi H, et al. Quality of life one year after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(3):171.

Rahnavard Z, Zolfaghari M, Kazemnejad A, Hatamipour K. An investigation of quality of life and factors affecting it in the patients with congestive heart failure. HAYAT. 2006;12(1):77–86.

Azami-Aghdash S, Gharaee H, Aghaei MH, Derakhshani N. Cardiovascular diseases patient’s quality of life in Tabriz-Iran: 2018. J Community Health Res. 2019;8(4):245–52.

Abedi HA, Yasaman-Alipour M, Abdeyazdan GH. Quality of life in heart failure patients referred to the Kerman outpatient centers, 2010. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2011;13(5):55–63.

Taghadosi M, Gilasi H. The general and specific quality of life in patients with Ischemia in Kashan. IJNR. 2008;3(9 & 8–9):39–46.

MontazerGhaem S, Asar O, Safaei N. Assessing patientś quality of life after open hart surgery in Bandar Abbass, Iran. Horm Med J. 2012;15(4):254–9.

Hasanpour A, Hasanpour M, Foruzandeh N, Ganji F, Asadi Noghani AA, Bakhsha F, et al. A survey on quality of life in patients with myocardial infarction, referred to Shahrekord Hagar hospital in 2005. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2007;9(3):78–84.

Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, O’Brien M, McCarthy M Jr, MaWhinney S, Shroyer ALW, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(6):2026–32.

Azizi F, Ghanbarian A, Momenan AA, Hadaegh F, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, et al. Prevention of non-communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran lipid and glucose study phase II. Trials. 2009;10(1):5.

Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H, Mirmiran P, Hajipour R, Madjid M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study (phase 1). Sozial- und Präventivmedizin. 2002;47(6):408–26.

Momenan AA, Delshad M, Sarbazi N, Rezaei GN, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Reliability and validity of the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ) in an Iranian urban adult population. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(5):279–82.

Lear SA, Hu W, Rangarajan S, Gasevic D, Leong D, Iqbal R, et al. The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: the PURE study. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2643–54.

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Asadi-Lari M, Omidvari S, Tavousi M. The 12-item medical outcomes study short form health survey version 2.0 (SF-12v2): a population-based validation study from Tehran, Iran. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):12.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–52.

Association AD. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Supplement 1):S81–90.

Levey A, Coresh J. Part 4. Definition and classification of stages of chronic kideny disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S46–75.

Hadaegh F, Harati H, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Association of total cholesterol versus other serum lipid parameters with the short-term prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(4):571–7.

Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Li C, McGuire LC, Strine TW, Okoro CA, et al. Gender differences in coronary heart disease and health-related quality of life: findings from 10 states from the 2004 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Womens Health. 2008;17(5):757–68.

De Smedt D, Clays E, Annemans L, Pardaens S, Kotseva K, De Bacquer D. Self-reported health status in coronary heart disease patients: a comparison with the general population. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(2):117–25.

Beyranvand M-R, Lorvand A, Parsa SA, Motamedi M-R, Kolahi A-A. The quality of life after first acute myocardial infarction. Pajoohande. 2011;15(6):264–72.

Stull D, Starling R, Haas G, Young J. Becoming a patient with heart failure. Heart & Lung J Crit Care. 1999;28:284–92.

Lane D, Carroll D, Ring C, Beevers DG, Lip GY. The prevalence and persistence of depression and anxiety following myocardial infarction. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7(1):11–21.

Afilalo J, Karunananthan S, Eisenberg MJ, Alexander KP, Bergman H. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(11):1616–21.

Young RF, Kahana E. Gender, recovery from late life heart attack and medical care. Women Health. 1993;20(1):11–31.

Dueñas M, Ramirez C, Arana R, Failde I. Gender differences and determinants of health related quality of life in coronary patients: a follow-up study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11(1):24.

Prata J, Martins AQ, Ramos S, Rocha-Gonçalves F, Coelho R. Gender differences in quality of life perception and cardiovascular risk in a community sample. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Edit). 2016;35(3):153–60.

Walli-Attaei M, Joseph P, Rosengren A, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Lear SA, et al. Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;396(10244):97–109.

Emery CF, Frid DJ, Engebretson TO, Alonzo AA, Fish A, Ferketich AK, et al. Gender differences in quality of life among cardiac patients. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):190–7.

Jalali-Farahani S, Amiri P, Karimi M, Vahedi-Notash G, Amirshekari G, Azizi F. Perceived social support and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in Tehranian adults: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):90.

Bahall M, Legall G, Khan K. Quality of life among patients with cardiac disease: the impact of comorbid depression. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):1–10.

Wiklund I, Herlitz J, Johansson S, Bengtson A, Karlson B, Persson N. Subjective symptoms and well-being differ in women and men after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1993;14(10):1315–9.

Hemingway H, Langenberg C, Damant J, Frost C, Pyörälä K, Barrett-Connor E. Prevalence of angina in women versus men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international variations across 31 countries Circulation. 2008;117(12):1526–36.

Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, Roe M, Granger CB, Armstrong PW, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302(8):874–82.

Hansen KW, Sørensen R, Madsen M, Madsen J, Jensen J, Von Kappelgaard L, et al. Developments in the invasive diagnostic–therapeutic cascade of women and men with acute coronary syndromes from 2005 to 2011: a nationwide cohort study. BMJ open. 2015;5(6):e007785.

Anand SS, Xie CC, Mehta S, Franzosi MG, Joyner C, Chrolavicius S, et al. Differences in the management and prognosis of women and men who suffer from acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(10):1845–51.

EUGenMed CCS Group, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S, Prescott E, Franconi F, et al. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):24–34.

Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Bettoncelli G, Cricelli C, Romeo F, Matera MG, et al. Cardiovascular disease in asthma and COPD: a population-based retrospective cross-sectional study. Respir Med. 2012;106(2):249–56.

Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, Josephson R, Hughes J, Gunstad J. COPD is associated with cognitive dysfunction and poor physical fitness in heart failure. Heart Lung. 2015;44(1):21–6.

Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Ntetu AL, Maltais D. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):1–12.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to all participants who made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PA and SJF designed the study. LCh participated in acquisition of data and carried out the statistical analysis. PA and SJF contributed to interpretation of data. SJF, HF and KT drafted the manuscript. PA, DKh and FA supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences (RIES), Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jalali-Farahani, S., Amiri, P., Fakhredin, H. et al. Health-related quality of life in men and women who experienced cardiovascular diseases: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19, 225 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01861-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01861-2