Abstract

Background

Receptive injection equipment sharing (i.e., injecting with syringes, cookers, rinse water previously used by another person) plays a central role in the transmission of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, viral hepatitis) among people who inject drugs. Better understanding these behaviors in the context of COVID-19 may afford insights about potential intervention opportunities in future health crises.

Objective

This study examines factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing among people who inject drugs in the context of COVID-19.

Methods

From August 2020 to January 2021, people who inject drugs were recruited from 22 substance use disorder treatment programs and harm reduction service providers in nine states and the District of Columbia to complete a survey that ascertained how the COVID-19 pandemic affected substance use behaviors. We used logistic regression to identify factors associated with people who inject drugs having recently engaged in receptive injection equipment sharing.

Results

One in four people who inject drugs in our sample reported having engaged in receptive injection equipment sharing in the past month. Factors associated with greater odds of receptive injection equipment sharing included: having a high school education or equivalent (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.14, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.24, 3.69), experiencing hunger at least weekly (aOR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.01, 3.56), and number of drugs injected (aOR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.02, 1.30). Older age (aOR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.94, 1.00) and living in a non-metropolitan area (aOR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.18, 1.02) were marginally associated with decreased odds of receptive injection equipment sharing.

Conclusions

Receptive injection equipment sharing was relatively common among our sample during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings contribute to existing literature that examines receptive injection equipment sharing by demonstrating that this behavior was associated with factors identified in similar research that occurred before COVID. Eliminating high-risk injection practices among people who inject drugs requires investments in low-threshold and evidence-based services that ensure persons have access to sterile injection equipment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High-risk injection practices, such as receptive injection equipment sharing (i.e., injecting with syringes, cookers, rinse water that were previously used by another person), play a central role in the transmission of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, viral hepatitis) among people who inject drugs (PWID) [1,2,3,4]. In the United States (US), there are an estimated 750,000 people who injected drugs in the past year [5]. Studies have found that the prevalence of receptive injection equipment sharing among PWID varies across the United States and has been associated with infectious disease outbreaks [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. For example, a study conducted in Baltimore City (Maryland) found that 16% of PWID reported having engaged in receptive syringe sharing in the past month [7]. Another study conducted among PWID in a rural county in West Virginia found that 43% reported engaging in receptive syringe sharing in the past 6 months [9]. Similarly, a study conducted in Kentucky found that 30.2% of a sample of PWID living with viral hepatitis reported having recently engaged in receptive syringe sharing [4]. These and other findings underscore the continued need for comprehensive interventions that increase access to sterile injection equipment.

Several decades of research have been conducted to better understand unsafe injection practices among PWID. For example, prior studies have identified that these behaviors are driven by the intersections of individual- and structural-level factors, substance use, social context, and policy [7, 9, 13, 16]. Inadequate access to sterile injection equipment has also been associated with syringe sharing [20,21,22]. Mitigating the consequences of high-risk injection practices (e.g., infectious disease acquisition) may be achieved through the implementation of interventions that aim to increase access to sterile injection equipment, including syringe services programs (SSPs) [23,24,25,26]. However, many communities lack SSPs due to restrictive policies, community-level opposition, and inaccurate fears that they may increase substance use, crime, or syringe litter [20, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Stigma and discrimination against people who use drugs also negatively affect the implementation and utilization of SSPs and other evidence-based response strategies, such as medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).

The COVID-19 pandemic had far-reaching effects on public health, including among PWID. In some instances, SSPs closed or modified their operations to reduce COVID-19 transmission risks [36,37,38,39,40]. Some SSPs also had inadequate staffing during the pandemic which led to decreased service availability, such as onsite HIV and hepatitis testing [36]. Further, pandemic lockdowns also resulted in reductions in syringe distribution and infectious disease testing [41]. Mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness) worsened among people who use drugs during the pandemic [37, 42, 43]. In terms of substance use disorder treatment, a 2022 study found that there were substantial reductions in in-person services, but policy changes that provided flexibilities in treatment delivery (e.g., increased take-home medications, counseling by video/phone, and fewer urine drug screens) were well-received among people with histories of substance use [44]. Other COVID-19 era research has found that PWID struggled to get appointments with HIV counselors and physicians and that access to preexposure prophylaxis diminished during the pandemic [45, 46].

Although existing research demonstrates several ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic affected PWID, limited research has been conducted to understand its impact on high-risk injection practices. One study found that syringe reuse was more common during the pandemic [43], but this was limited to a sample of PWID in New York City and may not be generalizable to other settings. Given that receptive injection equipment sharing is strongly associated with infectious disease transmission among PWID, better understanding this behavior in the context of COVID-19 may afford key insights about potential intervention opportunities in the ongoing pandemic and in ensuring sustainable access to sterile supplies in the future. This study utilizes data from a multistate survey conducted in late 2020 and early 2021 to examine factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing among PWID.

Methods

Study context

From August 2020 to January 2021, study participants were recruited from 22 substance use disorder treatment programs and harm reduction service providers in nine states (Maine, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia. Most participating drug treatment programs and harm reduction providers were engaged in the Bloomberg Opioid Initiative (a campaign supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies that aims to reduce overdose rates). Staff at collaborating organizations distributed study recruitment cards to clients. Each card featured the study logo, the study phone number, and a unique study identifier (to reduce duplicate and non-client participation). Persons who were interested in participating in the study contacted the data collection team via phone and were subsequently able to ask questions and be screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, a current client of a collaborating organization, able to provide informed consent, and able to provide an unused unique study identifier. Participants received $40 compensation via a pre-paid gift card or Venmo payment. Overall, 587 responses were collected. Given our interest in receptive injection equipment sharing among PWID, we restricted the analytic sample to participants who had injected drugs in the past month (n = 266). We further removed a transgender participant to ensure their anonymity was protected. This research was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Receptive injection equipment sharing in the past month

Participants answered two questions about their receptive injection equipment sharing behaviors in the past month. Participants indicated if they had used a syringe or needle after someone else had used it and if they had used other injection equipment, like cookers or rinse water, after someone else. These two indicators had a high degree of overlap (85% of persons who shared syringes also shared other equipment); as a result, we created a binary indicator for receptive sharing of any injection equipment in the past month.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Participants reported their age (in years), gender (man/woman), relationship status (single/in a relationship or married), sexual orientation (heterosexual or straight/sexual minority), education level (less than high school, high school diploma or equivalent, or some college or more), and employment status (full time, part time, not working). Participants reported their race and ethnicity, which we dichotomized to non-Hispanic White and Racial/Ethnic Minority (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Multiracial/Multiethnic) due to sample size constraints. Participants further reported if they were currently homeless (yes/no), if they experienced hunger (defined as going to bed hungry due to lack of food) at least once a week since the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), if they had ever tested positive for HIV (yes/no), and if they traded sex for drugs or money since the pandemic started (yes/no). Based on the county participants reported living in, we created an urbanicity measure using the National Center for Health Statistics Rural Classification Scheme (codes range from 1– large central metro to 6 – non-core). We created a three-category measure of urbanicity: large metropolitan (codes 1 and 2), small metropolitan (codes 3 and 4), and non-metropolitan (codes 5 and 6).

Injection drug use in the past month

We created binary indicators of whether participants reported having injected each of the following drugs/combinations of drugs in the past month: cocaine, heroin, fentanyl, heroin and fentanyl simultaneously, speedball (cocaine and heroin simultaneously), methamphetamine, methamphetamine and heroin simultaneously, prescription opioids, tranquilizers, and buprenorphine (e.g., Suboxone). We also created a variable that reflected the total number of drugs/combinations of drugs injected in the past month.

COVID-related drug use behavior changes

We included four measures of drug use-related behavior changes during COVID-19. First, we asked participants to indicate how often they injected drugs per day during COVID-19 relative to the pre-COVID era (less frequently, the same, more frequently). Participants indicated how often they used drugs with others during COVID-19 relative to before the pandemic (less frequently, the same, more frequently). Participants further indicated if they used mostly in private locations during COVID-19 (yes/no) and if they had avoided accessing syringe services programs due to COVID-19 fears (yes/no).

Service utilization

We included three binary measures of drug treatment engagement. First, we created an indicator for any past-month drug treatment. We then created two indicators for the type of treatment received: any MOUD (buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone) and any non-MOUD treatment. The treatment types were not mutually exclusive. We also asked participants whether they had acquired sterile syringes from a syringe services program in the past month (yes/no).

Analysis

We first estimated the prevalence of past month receptive injection equipment sharing in our sample. We used Chi Square and t-tests, as appropriate, to assess bivariate relationships between variables and receptive injection equipment sharing. We used logistic regression to identify factors associated with PWID having recently engaged in receptive injection equipment sharing. We considered all correlates of receptive injection equipment sharing at the p < 0.2 level for inclusion in multivariable logistic regression analyses. We elected to utilize the number of drugs injected instead of individual drug measures to achieve a more parsimonious model. We further excluded two variables (homelessness and MOUD treatment) from the multivariable model due to collinearity with other included variables (hunger and any drug treatment, respectively). In the multivariable logistic regression model, standard errors were clustered by the provider participants were recruited from to account for study design. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

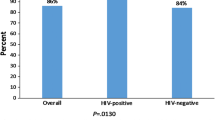

The average age of the sample was 39 years old (SD: 10.5). Half (50.2%) the participants were women and 62.9% identified as non-Hispanic White (Table 1). Fourteen percent identified as a sexual minority. Few (4.9%) reported having HIV. Over half (56.8%) of participants were in a relationship. Having a high school education was the most common education level (45.7%); the prevalence of having less than a high school education (27.2%) or some college or more (27.2%) were similar. Most (85.3%) participants were not working. About one-quarter (27.7%) of participants were homeless and one-third (34.3%) reported weekly hunger. Urbanicity level varied (39.0% large metropolitan, 37.5% small metropolitan, 23.5% non-metropolitan). Approximately eleven percent (10.6%) reported engaging in transactional sex. On average, participants reported injecting three drugs in the past month. Most (85.6%) had accessed an SSP in the past month. One-third (32.1%) of participants reported more frequent drug injection during COVID-19. Just under half (46.0%) had received drug treatment in the past month. One in four participants reported having engaged in receptive injection equipment sharing in the past month.

At the bivariate level (Table 1), participants who reported receptive injection equipment sharing were significantly younger than persons who did not (p = 0.04). Participants who identified as sexual minorities (p = 0.03), as non-Hispanic White (p = 0.004), experienced hunger at least weekly (p = 0.04), and who engaged in transactional sex (p = 0.02) were significantly more likely than their counterparts to report receptive injection equipment sharing. Participants with a high school education were more likely to report receptive injection equipment sharing than participants with other education levels (p = 0.01). Use of speedball (p = 0.03), methamphetamine (p = 0.003), and methamphetamine and heroin (p = 0.005) were all significantly associated with receptive injection equipment sharing. Participants who reported receptive injection equipment sharing, on average, used significantly more drugs than persons who did not (p = 0.006). Individuals who reported increased injection frequency during COVID-19 were significantly more likely to report receptive injection equipment sharing than persons who reported the same or less frequent injection (p = 0.02).

In the multivariable model (Table 2), having a high school education or equivalent was associated with greater odds of receptive injection equipment sharing compared to having less than a high school education (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.14, 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI] 1.24, 3.69). Experiencing weekly hunger (aOR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.01, 3.56) and number of drugs injected (aOR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.02, 1.30) were also associated with greater odds of receptive injection equipment sharing. Older age (aOR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.94, 1.00) and living in a non-metropolitan area (aOR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.18, 1.02) were marginally associated with decreased odds of receptive injection equipment sharing.

Discussion

Using data from a geographically diverse sample of PWID during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that approximately one in four participants reported having recently engaged in receptive injection equipment sharing. Factors associated with greater odds of recent receptive injection equipment sharing included experiencing hunger, number of drugs injected, and having a high school diploma. Our findings contribute to existing literature that examines receptive injection equipment sharing by demonstrating that this behavior was associated with factors identified in similar research that occurred before COVID-19 [7, 9, 47, 48]. Eliminating infectious disease transmission among PWID will require novel, low-threshold interventions (e.g., peer-led SSPs, harm reduction vending machines, no-cost access to mail-order harm reduction supplies) that ensure PWID have access to sterile injection equipment during times of co-occurring crises.

We found that 34% of our sample reported experiencing weekly hunger and that hunger was associated with greater odds of receptive injection equipment sharing. These findings parallel similar research conducted among PWID before the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, food insecurity has been associated with PWID engaging in high-risk behaviors (e.g., syringe sharing, condomless sex) for HIV/STI acquisition in prior research [9, 47,48,49]. For PWID with insufficient food access, obtaining food may compete with persons’ engagement in health-promoting behaviors, such as always using sterile injection equipment. It is also plausible that hunger is a proxy for a mosaic of structural vulnerabilities (e.g., homelessness, unemployment) and having less agency to engage in risk minimizing behaviors. Among PWID living with HIV, research has also shown that inadequate food access increases severity of infectious diseases [50, 51]. Communities should work to guarantee no person struggles with hunger. Strategies to mitigate hunger among PWID, and communities more broadly, should be holistic in nature given the overlapping nature of hunger with other structural vulnerabilities, including homelessness. Comprehensively addressing structural vulnerabilities among PWID may carry significant public health benefits via supporting reductions in high-risk injection behaviors. Future work should be conducted to identify exemplar models of care that integrate the provision of harm reduction services and food access. Notably, there are examples of service providers that integrate food provision and harm reduction [52,53,54].

Similar to research conducted before COVID-19, we found that the number of drugs PWID injected was positively associated with receptive injection equipment sharing [9]. This finding may be partially explained by associated needs for sterile injection equipment, i.e., persons who inject more types of drugs may require larger volumes of sterile injection equipment, including syringes. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic reduced access to SSPs, it is also plausible that PWID may have had challenges ensuring they had a sterile syringe and other supplies for each injection [55]. Further, many communities lack SSP access, potentially exacerbating risks for receptive injection equipment sharing [26]. Future work should be conducted to develop innovative strategies that afford PWID reliable and low threshold access to sterile injection equipment. Exemplar strategies to increase access to sterile injection equipment may include public health vending machines, mail order injection supplies, and distributing supplies at retail venues (e.g., pharmacies). Peer-based SSPs may also be particularly effective at reaching vulnerable PWID [56, 57].

We found that living in a non-metropolitan area was marginally associated with decreased odds of recent injection equipment sharing. This finding warrants additional study given that many injection drug use-associated HIV outbreaks in rural communities have occurred in recent years [17,18,19, 58]. Further, analyses that examined risks for injection drug use-associated HIV outbreaks identified many rural counties throughout the United States as vulnerable [59]. Though methodological differences limit comparability across studies (e.g., we recruited PWID who accessed services at drug treatment and harm reduction programs, which may be of limited availability in non-urban areas), receptive injection equipment sharing has been shown to be a relatively common phenomenon among rural PWID [3, 13, 15, 60, 61]. Our finding that non-metropolitan residence was associated with decreased odds of recent injection equipment sharing may also reflect both the considerable heterogeneity in where we recruited participants as well as how we operationalized urbanicity. Nevertheless, future studies should be conducted to more comprehensively understand factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing among rural PWID and if these relationships are affected by the degree to which persons access drug treatment and harm reduction services.

It is important to interpret the findings of this study relative to its limitations. Our outcome focused on PWID engaging in receptive injection equipment sharing in the past month. As such, we are only able to glean a snapshot of receptive injection equipment sharing among our participants rather than more comprehensive examinations of this behavior and how it may vary by context over time. Additionally, there is considerable variation in how high-risk injection practices are measured in the literature, limiting our ability to make direct comparisons. Due to sample size limitations, we trichotomized our measure of urbanicity. More robust sample sizes may afford nuanced analyses across the urban–rural continuum. In addition, we found that education was significantly associated with receptive injection equipment sharing; however, this finding should be interpreted with caution given both sample size constraints and our sampling strategy. Future lines of scientific inquiry should explore the role of educational attainment and engagement in high-risk injection practices. Efforts should also be undertaken to ensure PWID receive evidence-based education about the risks of sharing injection equipment. Another potential limitation relates to sampling bias given that we recruited persons from substance use disorder and harm reduction service providers in nine states and the District of Columbia. Our findings should not be considered representative of PWID across the US, nor reflective of the experiences of PWID who do not access substance use disorder treatment facilities or harm reduction services. Though our study is not without limitations, it contributes to the public health literature by examining factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing among a sample of geographically diverse PWID during the early months of a global pandemic.

In conclusion, we found that a quarter of PWID who were connected to drug treatment and harm reduction service providers reported receptive injection equipment sharing during the early months of the global COVID-19 pandemic, and that these behaviors varied according to education level, hunger, urbanicity and number of drugs injected. We also found that PWID residing in non-metropolitan communities had marginally decreased odds of receptive injection equipment sharing. Factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing in our study had both similarities and differences to prior research. The COVID-19 pandemic affected risks for infectious disease acquisition among PWID throughout the world, and our results shed light on the high-risk injection practices among PWID that contributed to enduring infectious disease risks during the pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

Deidentified data that supported the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SSP:

-

Syringe services programs

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

References

Prevention CfDCa. HIV and substance use. 2021.

Ball LJ, Puka K, Speechley M, Wong R, Hallam B, Wiener JC, et al. Sharing of injection drug preparation equipment is associated with HIV infection: a cross-sectional study. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4):e99–103.

Zibbell JE, Hart-Malloy R, Barry J, Fan L, Flanigan C. Risk factors for HCV infection among young adults in rural New York who inject prescription opioid analgesics. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2226–32.

Havens JR, Lofwall MR, Frost SD, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG, Crosby RA. Individual and network factors associated with prevalent hepatitis C infection among rural Appalachian injection drug users. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):e44-52.

Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, Holtzman D, Wejnert C, Mitsch A, et al. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the United States by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97596.

Beletsky L, Heller D, Jenness SM, Neaigus A, Gelpi-Acosta C, Hagan H. Syringe access, syringe sharing, and police encounters among people who inject drugs in New York City: a community-level perspective. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):105–11.

Hunter K, Park JN, Allen ST, Chaulk P, Frost T, Weir BW, et al. Safe and unsafe spaces: non-fatal overdose, arrest, and receptive syringe sharing among people who inject drugs in public and semi-public spaces in Baltimore City. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:25–31.

Neaigus A, Reilly KH, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C. Dual HIV risk: receptive syringe sharing and unprotected sex among HIV-negative injection drug users in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2501–9.

White RH, O’Rourke A, Kilkenny ME, Schneider KE, Weir BW, Grieb SM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of receptive syringe-sharing among people who inject drugs in rural Appalachia. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2021;116(2):328–36.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1192–207.

Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Lozada RM, Ramos R, Cruz MF, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Syringe possession arrests are associated with receptive syringe sharing in two Mexico-US border cities. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2008;103(1):101–8.

Muñoz F, Burgos JL, Cuevas-Mota J, Teshale E, Garfein RS. Individual and socio-environmental factors associated with unsafe injection practices among young adult injection drug users in San Diego. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):199–210.

Grau LE, Zhan W, Heimer R. Prevention knowledge, risk behaviours and seroprevalence among nonurban injectors of southwest Connecticut. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35(5):628–36.

Heimer R, Barbour R, Palacios WR, Nichols LG, Grau LE. Associations between injection risk and community disadvantage among suburban injection drug users in southwestern Connecticut, USA. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):452–63.

Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(1):98–102.

Havens JR, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG. Injection risk behaviors among rural drug users: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):638–45.

Atkins A, McClung RP, Kilkenny M, Bernstein K, Willenburg K, Edwards A, et al. Notes from the field: outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among persons who inject drugs—Cabell County, West Virginia, 2018–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(16):499–500.

Conrad C, Bradley HM, Broz D, Buddha S, Chapman EL, Galang RR, et al. Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone-Indiana, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(16):443–4.

Hershow RB, Wilson S, Bonacci RA, Deutsch-Feldman M, Russell OO, Young S, et al. Notes from the field: HIV outbreak during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons who inject drugs—Kanawha County, West Virginia, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(2):66–8.

Allen ST, Grieb SM, O’Rourke A, Yoder R, Planchet E, White RH, et al. Understanding the public health consequences of suspending a rural syringe services program: a qualitative study of the experiences of people who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):33.

Allen ST, White RH, O’Rourke A, Schneider KE, Weir BW, Lucas GM, et al. Syringe coverage among people who inject drugs in West Virginia, USA. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(10):3377–85.

Bluthenthal RN, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Higher syringe coverage is associated with lower odds of HIV risk and does not increase unsafe syringe disposal among syringe exchange program clients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2–3):214–22.

Ruiz MS, O’Rourke A, Allen ST. Impact evaluation of a policy intervention for HIV prevention in Washington, DC. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):22–8.

Ruiz MS, O’Rourke A, Allen ST, Holtgrave DR, Metzger D, Benitez J, et al. Using interrupted time series analysis to measure the impact of legalized syringe exchange on HIV diagnoses in Baltimore and Philadelphia. J Acquir immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2019;82(Suppl 2):S148–54.

Jones CM. Syringe services programs: an examination of legal, policy, and funding barriers in the midst of the evolving opioid crisis in the U.S. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:22–32.

Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D. Syringe service programs for persons who inject drugs in urban, suburban, and rural areas—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(48):1337–41.

Allen ST, Grieb S, Glick JL, White RH, Puryear T, Smith KC, Weir BW, Sherman SG. Applications of research evidence during processes to acquire approvals for syringe services program implementation in rural counties in Kentucky. Ann Med. 2022;54:404–12.

Broadhead RS, van Hulst Y, Heckathorn DD. The impact of a needle exchange’s closure. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC: 1974). 1999;114(5):439–47.

Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Junge B, Rathouz PJ, Galai N, et al. Discarded needles do not increase soon after the opening of a needle exchange program. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(8):730–7.

Doherty MC, Junge B, Rathouz P, Garfein RS, Riley E, Vlahov D. The effect of a needle exchange program on numbers of discarded needles: a 2-year follow-up. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):936–9.

Galea S, Ahern J, Fuller C, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Needle exchange programs and experience of violence in an inner city neighborhood. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2001;28(3):282–8.

Marx MA, Crape B, Brookmeyer RS, Junge B, Latkin C, Vlahov D, et al. Trends in crime and the introduction of a needle exchange program. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1933–6.

Oliver KJ, Friedman SR, Maynard H, Magnuson L, Des Jarlais DC. Impact of a needle exchange program on potentially infectious syringes in public places. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5(5):534–5.

Sherman SG, Purchase D. Point defiance: a case study of the United States’ first public needle exchange in Tacoma, Washington. Int J Drug Policy. 2001;12(1):45–57.

CDC. Syringe services programs (SSPs): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/index.html. Updated 23 May 2019.

Bartholomew TS, Nakamura N, Metsch LR, Tookes HE. Syringe services program (SSP) operational changes during the COVID-19 global outbreak. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102821.

Bolinski RS, Walters S, Salisbury-Afshar E, Ouellet LJ, Jenkins WD, Almirol E, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug use behaviors, fentanyl exposure, and harm reduction service support among people who use drugs in rural settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2230.

Frost MC, Sweek EW, Austin EJ, Corcorran MA, Juarez AM, Frank ND, et al. Program adaptations to provide harm reduction services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of syringe services programs in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(1):57–68.

Glick SN, Prohaska SM, LaKosky PA, Juarez AM, Corcorran MA, Des Jarlais DC. The impact of COVID-19 on syringe services programs in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(9):2466–8.

Whitfield M, Reed H, Webster J, Hope V. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on needle and syringe programme provision and coverage in England. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102851.

Trayner KMA, McAuley A, Palmateer NE, Yeung A, Goldberg DJ, Glancy M, et al. Examining the impact of the first wave of COVID-19 and associated control measures on interventions to prevent blood-borne viruses among people who inject drugs in Scotland: an interrupted time series study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;232:109263.

Nguyen TT, Hoang GT, Nguyen DQ, Nguyen AH, Luong NA, Laureillard D, et al. How has the COVID-19 epidemic affected the risk behaviors of people who inject drugs in a city with high harm reduction service coverage in Vietnam? A qualitative investigation. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):6.

Aponte-Melendez Y, Mateu-Gelabert P, Fong C, Eckhardt B, Kapadia S, Marks K. The impact of COVID-19 on people who inject drugs in New York City: increased risk and decreased access to services. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):118.

Saloner B, Krawczyk N, Solomon K, Allen ST, Morris M, Haney K, et al. Experiences with substance use disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a multistate survey. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;101:103537.

Mistler CB, Curley CM, Rosen AO, El-Krab R, Wickersham JA, Copenhaver MM, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on access to HIV prevention services among opioid-dependent individuals. J Community Health. 2021;46(5):960–6.

Gleason E, Nolan NS, Marks LR, Habrock T, Liang SY, Durkin MJ. Barriers to care experienced by patients who inject drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. J Addict Med. 2021;16:e133–6.

Rouhani S, Allen ST, Whaley S, White RH, O’Rourke A, Schneider KE, et al. Food access among people who inject drugs in West Virginia. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):90.

Strike C, Rudzinski K, Patterson J, Millson M. Frequent food insecurity among injection drug users: correlates and concerns. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1058.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Milloy MJ, Anema A, Zhang R, Montaner JS, et al. Severe food insecurity is associated with elevated unprotected sex among HIV-seropositive injection drug users independent of HAART use. AIDS (Lond, Engl). 2011;25(16):2037–42.

The LH. The syndemic threat of food insecurity and HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2):e75.

Anema A, Chan K, Chen Y, Weiser S, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Relationship between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-positive injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61277.

BOOM!Health. Available at: https://www.boomhealth.org/. Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

St. Ann's Corner of Harm Reduction. https://www.sachr.org/. Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

Feed Louisville. https://www.feedlouisville.org/. Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

Harris SJ, Meyer A, Whaley S, Shah H, Bhagwat A, Allen ST, Krawczyk N, Solomon K, Sherman S, Saloner B. In their own words: experiences of people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2022.

Hayashi K, Wood E, Wiebe L, Qi J, Kerr T. An external evaluation of a peer-run outreach-based syringe exchange in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(5):418–21.

Wood E, Kerr T, Spittal PM, Small W, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. An external evaluation of a peer-run “unsanctioned” syringe exchange program. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2003;80(3):455–64.

Bradley H, Hogan V, Agnew-Brune C, Armstrong J, Broussard D, Buchacz K, et al. Increased HIV diagnoses in West Virginia counties highly vulnerable to rapid HIV dissemination through injection drug use: a cautionary tale. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;34:12–7.

Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):323–31.

Paquette CE, Pollini RA. Injection drug use, HIV/HCV, and related services in nonurban areas of the United States: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:239–50.

Young AM, Jonas AB, Mullins UL, Halgin DS, Havens JR. Network structure and the risk for HIV transmission among rural drug users. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2341–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of colleagues at Vital Strategies and Pew Charitable Trusts, the study advisory board, and programs that helped distribute client cards. Most importantly, we are grateful to our study participants.

Funding

The study was supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies. STA is also supported by the National Institutes of Health (K01DA046234). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, or in analysis and interpretation of the results, and this paper does not necessarily reflect views or opinions of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

STA, MM, SJH, BS, and SGS were involved in the conception of the study. STA and KES were involved in the analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the findings. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agree to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, S.T., Schneider, K.E., Morris, M. et al. Factors associated with receptive injection equipment sharing among people who inject drugs: findings from a multistate study at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J 20, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00746-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00746-5