Abstract

Background

Injection drug use and needle sharing remains a public health concern due to the associated risk of HIV, HCV and skin and soft tissue infections. Studies have shown gendered differences in the risk environment of injection drug use, but data are currently limited to smaller urban cohorts.

Methods

To assess the relationship between gender and needle sharing, we analyzed publicly available data from the 2010–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) datasets. Chi-square tests were conducted for descriptive analyses and multivariable logistic regression models were built adjusting for survey year, age, HIV status, and needle source.

Results

Among the entire sample, 19.8% reported receptive needle sharing, 18.8% reported distributive sharing of their last needle, and 37.0% reported reuse of their own needle during last injection. In comparison with men, women had 34% increased odds (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.11–1.55) of receptive needle sharing and 67% increased odds (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.41–1.98) of distributive needle sharing. Reuse of one's own needle did not differ by gender.

Conclusions

In this nationally representative sample, we found that women are more likely in comparison with men to share needles both through receptive and distributive means. Expansion of interventions, including syringe service programs, to increase access to sterile injection equipment is of great importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rates of infections and related hospitalizations are rising among people who inject drugs (PWID) in large part driven by the opioid epidemic [1, 2] and the sharing of non-sterile injecting equipment. In particular, sharing of equipment increases the risk for HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) [3,4,5]. An analysis of county-level vulnerability identified over 200 counties across 26 states at high risk for an outbreak of HIV or HCV due to shared injection equipment [6]. The rapid outbreaks of HIV among networks of PWID in Indiana and Massachusetts further underscore this risk and the need for expansion of targeted harm reduction programs [5, 7].

Prior work has identified the impact of gender on needle and works sharing [8, 9]. Women are more likely to initiate injection drug use in the context of a relationship [10, 11], share needles the first time they ever inject [12, 13], and receive “assisted injection,” a practice that involves one individual injecting another [14, 15], The sexual and power dynamics of injection partner dyads and networks also has been shown to increase the risk environment of women who inject drugs [16]. Prior work by our research team found an increased rate of skin and soft tissue infections among women who engaged in sex work, but not men [17].

However, research on sharing injection equipment, to date, has been limited to smaller urban cohorts and precedes the current era of ubiquitous synthetics drugs. With the rise of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids alongside the shifting geo-demographic patterns of injection drug use, the gendered patterns of works sharing may have shifted. An updated and national assessment of the influence of gender on works sharing is warranted to help guide harm reduction programs and advocacy efforts. In this paper, we investigate if there is an association between gender and needle sharing in a national dataset from 2010 to 2019.

Materials and methods

We analyzed ten years of data from the 2010–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) publicly available datasets, which included responses from a total of 564,177 participants across those ten years. Only participants who reported any injection drug use (IDU) were included in our analysis sample.

Our primary outcome of interest was the report (yes/no) that the last needle used had been previously used by another individual (“receptive needle sharing”). Our secondary outcome of interest was report (yes/no) of giving the last needle they had used to someone else following injection (“distributive needle sharing”). The primary indicator of interest was gender, recorded by NSDUH interviewers as women or men. Since the creation of the original NSDUH survey, there has increased attention to the importance of asking about gender and sex in ways that are respectful and inclusive. Recent analyses of NSDUH reported on gender [18], as such we framed our analysis of the survey item as gender. Other indicators of interest in our analysis included age, race, ethnicity, self-reported HIV status, source of last needle, and survey year. Descriptive analyses with chi-square tests were conducted to examine differences by gender. Multivariable logistic regression models were then built to further examine the relationship between gender and (1) distributive needle sharing and (2) receptive needle sharing. Multivariable models were adjusted for year, race/ethnicity, age, HIV status, and needle source. These variables were chosen a priori guided by prior studies [8, 9, 19, 20]. The NSDUH uses a stratified cluster design to select a representative sample of non-institutionalized people living in the USA. To account for the complex cluster design, all analyses were weighted using the survey package in R (v.4.0.0) and the variance estimation variables and final analysis weights provided in each NSDUH dataset.

Results

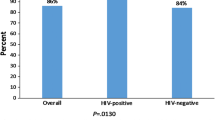

There were 7678 survey respondents who reported IDU (1.4% of NSDUH 2010–2019 responses). Most of the sample (79.5%) identified as non-Hispanic White, 42.2% were 50 years of age or older and most (98.5%) were HIV negative (Table 1). Half of participants reported obtaining the needle for their most recent IDU from a pharmacy (51.3%), and 5.4% reported obtaining the needle from a syringe service program (SSP). Nearly one in five respondents (19.8%) reported receptive needle sharing, and 18.7% reported distributive needle sharing. Two thirds (66%) of those who received a needle from another individual reported distributing the same needle following injection. About a third of all survey participants (37.0%) reported reuse of their own needle during last injection.

Women were more likely to both report receptive (p = 0.026) and distributive needle sharing (p < 0.001) in bivariate analyses. Reuse of one’s own needle did not differ by gender. In multivariable modeling, women were significantly more likely to report receptive and distributive needle sharing, adjusted for age, needle source, HIV status, race and ethnicity, and year of survey (Table 2). In comparison with men, women had 34% increased odds (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.12–1.59) of receptive needle sharing and 67% increased odds (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.41–1.98) of distributive needle sharing.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of PWID, we found that women were significantly more likely to report sharing of needles than men, both through receptive and distributive patterns. This finding may provide an explanation for the higher incidence of SSTIs that have been reported among women who inject drugs [17]. While the gender and characteristics of the needle sharing partner(s) are not reported in NSDUH, our results are suggestive that women who inject drugs may be at higher risk of bloodborne disease as a result of needle sharing practices.

Previous research has emphasized the role that social and environmental factors play in shaping injection behaviors for women. For instance, gendered violence and complex power dynamics has been shown to influence needle sharing practices, such that women are more likely to “go second on the needle” due to differential sexual, physical and environmental influences [16, 21, 22]. While gendered violence very likely contributes to our findings, our data also suggest a nuanced picture of injection practices among women. Women may be more likely to inject socially and provide needles to others. A majority of those in our sample who received a needle subsequently distributed or returned a needle, indicating individuals are injecting in pairs and/or larger networks. Social support and injecting with others present are protective factors against physical violence as well as fatal overdose, particularly with the rise of more potent synthetic drugs. Accordingly, interventions for risk reduction should balance the protective effects of injecting in groups with strategies to reduce needle sharing.

A secondary finding of our work is the substantial need for expanded harm reduction programs nationally, given the reported low frequency of obtaining a needle from an SSP (5.4%). Evidence-based harm reduction interventions are central to reducing needle sharing, decreasing transmission of HIV and HCV, and preventing unintentional overdose. Not only are SSPs able to provide sterile equipment, but these programs offer non-judgmental, free, and accessible testing and care services to PWID who may not contact other medical services. Secondary needle exchange programs from SSPs that provide individuals with sterile injection equipment for both the individual and their peer network may be a particularly effective strategy given our findings of sharing of injection equipment. Efforts to address barriers to accessing harm reduction programs will be critical to ensure that there are sites which are safe and accessible for all who need sterile injection equipment, including the expansion of safe consumption sites (or ‘overdose prevention sites’) [23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, an increased emphasis on addressing the specific needs of women who inject drugs will be crucial. Previous work has suggested the importance of integrated mental health services with harm reduction, as well as interventions that provided empowerment training to address gender-based violence [16, 27].

Our analysis is limited in that we can only assess behavior surrounding a participant’s last needle used which provides a limited snapshot into injection practices. Characteristics (e.g., gender, age, relationship with survey participant) of who the needle was shared with are not known. Additionally, given the NSDUH survey design, we were unable to assess sharing behaviors of nonbinary people, who may have distinct patterns of equipment sharing due to differing power dynamics and exposure to violence [28, 29]. Future research and expanded survey designs are crucial to better understand injection practices of all individuals. Another limitation of this dataset is that the NSDUH does not include those who are incarcerated and relies on people with an address or who are living in a shelter, which may not capture those who are street homeless and using substances. While the NSDUH has been shown to better represent PWID than other national surveys, our sample may have underestimated the prevalence of PWID given selection bias, as well as the stigma of reporting IDU behaviors [30]. This being said, in our analysis, we estimated the prevalence of PWID to be 1.4% of all surveyed participants in line with the most recent estimates of national PWID prevalence of 1.46% reported by Bradley and colleagues [31].

Conclusions

Harm reduction strategies aimed at reducing high-risk injections and IDU-related infection prevention programs should focus efforts to include gender-specific components that address the needs of women who inject drugs. These findings are particularly important in the context of the continued opioid epidemic and rising use of synthetic drugs, including fentanyl.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed for the current study are publicly available and published by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IDU:

-

Injection drug use

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

- NSDUH:

-

National Survey on Drug Use and Health

- SSP:

-

Syringe service program

- SSTIs:

-

Skin and soft tissue infections

References

Capizzi J, Leahy J, Wheelock H, Garcia J, Strnad L, Sikka M, et al. Population-based trends in hospitalizations due to injection drug use-related serious bacterial infections, Oregon, 2008 to 2018. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11): e0242165.

Kadri AN, Wilner B, Hernandez AV, Nakhoul G, Chahine J, Griffin B, et al. Geographic trends, patient characteristics, and outcomes of infective endocarditis associated with drug abuse in the United States From 2002 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19): e012969.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1192–207.

Levitt A, Mermin J, Jones CM, See I, Butler JC. Infectious diseases and injection drug use: public health burden and response. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Supplement_5):S213-7.

Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):229–39.

Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):323–31.

Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, Cranston K, Panneer N, Fukuda HD, et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(1):37–44.

Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. Gender differences in social network influence among injection drug users: perceived norms and needle sharing. J Urban Health Bull NY Acad Med. 2007;84(5):691–703.

Unger JB, Kipke MD, De Rosa CJ, Hyde J, Ritt-Olson A, Montgomery S. Needle-sharing among young IV drug users and their social network members: The influence of the injection partner’s characteristics on HIV risk behavior. Addict Behav. 2006;31(9):1607–18.

Barnhart KJ, Dodge B, Sayegh MA, Herbenick D, Reece M. Shared injection experiences: interpersonal involvement in injection drug practices among women. Subst Abuse. 2021;66:1–7.

Tuchman E. Women’s injection drug practices in their own words: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12(1):6.

Frajzyngier V, Neaigus A, Gyarmathy VA, Miller M, Friedman SR. Gender differences in injection risk behaviors at the first injection episode. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2–3):145–52.

Simmons J, Rajan S, McMahon JM. Retrospective accounts of injection initiation in intimate partnerships. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23(4):303–11.

Brothers S, Kral AH, Wenger L, Simpson K, Bluthenthal RN. Assisted injection provider practices and motivations in Los Angeles and San Francisco California 2016-18. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;66:103052.

McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, Kerr T. “People knew they could come here to get help”: an ethnographic study of assisted injection practices at a peer-run ‘unsanctioned’ supervised drug consumption room in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):473–85.

El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA. Women who use or inject drugs: an action agenda for women-specific, multilevel, and combination HIV prevention and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S182–90.

Wurcel AG, Burke D, Skeer M, Landy D, Heimer R, Wong JB, et al. Sex work, injection drug use, and abscesses: associations in women, but not men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:293–7.

Budenz A, Grana R. Cigarette brand use and sexual orientation: intersections with gender and race or ethnicity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E94.

Ball LJ, Puka K, Speechley M, Wong R, Hallam B, Wiener JC, et al. Sharing of injection drug preparation equipment is associated with HIV infection: a cross-sectional study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4): e99.

Golub ET, Strathdee SA, Bailey SL, Hagan H, Latka MH, Hudson SM, et al. Distributive syringe sharing among young adult injection drug users in five U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(Suppl 1):S30-38.

Harvey E, Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Ofner M, Archibald CP, Eades G, et al. A qualitative investigation into an HIV outbreak among injection drug users in Vancouver. Brit Columbia AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):313–21.

Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) [Internet]. Atlanta; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/index.html.

Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG, El-Bassel N. Structural interventions for HIV prevention among women who use drugs: a global perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2015(69 Suppl 2):S140-145.

Springer SA, Larney S, Alam-mehrjerdi Z, Altice FL, Metzger D, Shoptaw S. Drug treatment as HIV prevention among women and girls who inject drugs from a global perspective: progress, gaps, and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Supplement 2):S155–61.

Levengood TW, Yoon GH, Davoust MJ, Ogden SN, Marshall BDL, Cahill SR, et al. Supervised injection facilities as harm reduction: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5):738–49.

Gilbert L, Raj A, Hien D, Stockman J, Terlikbayeva A, Wyatt G. Targeting the SAVA (Substance Abuse, Violence, and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: a global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2015(69 Suppl 2):S118-127.

Aparicio-García ME, Díaz-Ramiro EM, Rubio-Valdehita S, López-Núñez MI, García-Nieto I. Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):66.

Scandurra C, Mezza F, Maldonato NM, Bottone M, Bochicchio V, Valerio P, et al. Health of non-binary and genderqueer people: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01453.

Bradley H, Rosenthal EM, Barranco MA, Udo T, Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES. Use of population-based surveys for estimating the population size of persons who inject drugs in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 5):S218–29.

Bradley H, Hall E, Asher A, Furukawa N, Jones CM, Shealey J, et al. Estimated number of people who inject drugs in the United States. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2022;ciac543.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality [K08HS026008-0,Wurcel]. The funding source had no role in the development, analysis, or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AGW and JZ conceived the idea of analysis. AGW, JZ, and KMR designed the analysis with input from RG and MM. JZ and KMR performed the analysis with assistance from RG. JZ, KMR, MM wrote the manuscript with edits and input from AGW and RR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rich, K.M., Zubiago, J., Murphy, M. et al. The association of gender with receptive and distributive needle sharing among individuals who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J 19, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00689-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00689-3