Abstract

Background

Exposure to noxious particles, including cigarette smoke and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and promotes inflammation and cell death in the lungs. We investigated the combined effects of cigarette smoking and PM2.5 exposure in patients with COPD, mice, and human bronchial epithelial cells.

Methods

The relationship between PM2.5 exposure and clinical parameters was investigated in patients with COPD based on smoking status. Alveolar destruction, inflammatory cell infiltration, and pro-inflammatory cytokines were monitored in the smoking-exposed emphysema mouse model. To investigate the mechanisms, cell viability and death and pyroptosis-related changes in BEAS-2B cells were assessed following the exposure to cigarette smoke extract (CSE) and PM2.5.

Results

High levels of ambient PM2.5 were more strongly associated with high Saint George’s respiratory questionnaire specific for COPD (SGRQ-C) scores in currently smoking patients with COPD. Combined exposure to cigarette smoke and PM2.5 increased mean linear intercept and TUNEL-positive cells in lung tissue, which was associated with increased inflammatory cell infiltration and inflammatory cytokine release in mice. Exposure to a combination of CSE and PM2.5 reduced cell viability and upregulated NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18 transcription in BEAS-2B cells. NLRP3 silencing with siRNA reduced pyroptosis and restored cell viability.

Conclusions

PM2.5 aggravates smoking-induced airway inflammation and cell death via pyroptosis. Clinically, PM2.5 deteriorates quality of life and may worsen prognosis in currently smoking patients with COPD.

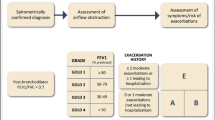

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic respiratory disease usually caused by prolonged exposure to noxious gases or particles [1]. Although cigarette smoking is an important risk factor in COPD, many patients with COPD are never-smokers [2,3,4]. Occupational exposure and biomass fuels are well-known risk factors in never-smoker COPD [5, 6]. Recent studies have linked particulate matter of diameter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5) to decreased lung function, airway inflammation, and emphysematous changes in the lungs, leading to the development of COPD and increased mortality [7,8,9,10].

Both PM2.5 and smoking have been reported to promote inflammation and cell death in the lungs [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Particularly, PM2.5 is known to induce various types of cell deaths, including autophagy, necrosis, apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis [17]. Recently, pyroptosis has been identified as a crucial process in lung injury. Pyroptosis is an inflammatory type of programmed cell death mediated by caspase-1 and activated by the inflammasome [18, 19]. The inflammasome is an intracellular multi-protein component composed primarily of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family and the pyrin and hematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear domain protein family [20]. NLR protein-3 (NLRP3) is an important member of NLR family that recognizes and is activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns or damage-associated molecular patterns [21, 22].

Recent reports have linked PM2.5 or smoking-induced pyroptosis to the development of COPD. In an in vitro COPD model exposed to cigarette smoke extract (CSE), NLRP3 activity was upregulated and augmented upon COPD exacerbation [23]. CSE induced pyroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells via the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway [24]. PM2.5 induced lung inflammation and pyroptosis in mice via the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway [25,26,27] and exacerbated cigarette smoke-induced changes in COPD animal model [28, 29]. However, the mechanism underlying the inflammation and cell death in the lungs of patients with COPD remains unclear. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of combined exposure to cigarette smoking and PM2.5 in real-world patients with COPD, smoking-exposed in vivo mouse model, and human cellular in vitro model.

Methods

Ambient PM2.5 concentration and clinical parameters in patients with COPD

We conducted a prospective cohort study at four referral hospitals in South Korea between 2019 and 2020, to assess the association between ambient PM2.5 concentrations and clinical parameters in patients with COPD over 1-year period. The detailed protocols [30, 31] and preliminary results [32] have been previously published. The study was individually approved by the Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided written informed consent.

Here, we performed a post-hoc analysis on correlations between PM2.5 exposure level and clinical parameters according to patients’ smoking status. The PM2.5 exposure level was measured using the actual exposure concentration of PM2.5. Clinical parameters included the Saint George’s respiratory questionnaire specific for COPD (SGRQ-C) and the number of acute exacerbations.

Animal model

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Asan Medical Center (approval number 2020-12-342). Female C57BL/6 mice (n = 22), 7 weeks old, weighing 18–19 g, were obtained from Orient Bio (Seongnam, Republic of Korea). Mice were randomly classified into four groups: control, smoking exposure, PM2.5 exposure, and smoking and PM2.5 combination exposure. The PM2.5 exposure group was exposed to 50 µg of PM2.5 per mouse (50 µg of PM2.5 in 30 µl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) by intratracheal instillation every 3 days for 4 weeks (10 times in total) [33]. The PM2.5 exposure dose was based on preliminary experiments (Fig. S1). The control group was administered 30 µl of PBS per mouse by intratracheal instillation every 3 days for 4 weeks (10 times in total). The smoking exposure group was exposed to cigarette smoke for 5 weeks (5 days/week) using 12 commercial cigarettes per day (4 cigarettes/session, 3 sessions/day, 8.0 mg tar/cigarette, and 0.70 mg nicotine/cigarette, Camel, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) via a whole-body apparatus according to a previously described protocol [34,35,36,37,38,39]. The control group inhaled only clean-room air (filtered air). In the real-world, people are exposed to PM, and to cigarette smoke superimposed to PM when smoking. Thus, experimental mice were exposed to PM2.5 prior to cigarette smoke. All mice were anesthetized by inhaled isoflurane and euthanized 6 weeks after the abovementioned treatment, and lung tissues and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were collected for further experiments.

Preparation of PM2.5 and CSE

PM2.5 was obtained by separating PM10 certified reference material (i.e., ERM-CZ100) using a modified sedimentation method [40]. First, 500 mg of ERM-CZ100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dispersed in 100 mL of 99.9% anhydrous ethanol (Samchun Chemicals, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and sonicated (DH.WUC. A03H, Daihan Scientific, Daegu, Republic of Korea) for 15 min. The sonicated PM10 solution was sedimented at room temperature for 30 min. To separate PM2.5 and solvent, 50 mL of the supernatant was centrifuged at 3220 x g for 5 min (Centrifuge 5810, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). After removing the supernatant, the PM2.5 was collected in a glass vial and dried at 80 °C in a vacuum oven to remove residual ethanol.

CSE was prepared as described previously [41]. Briefly, the smoke from 4 cigarettes (Camel, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) was drawn into a glass syringe containing 50 ml serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (Welgene, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea). The preparation was deemed 100% CSE. A 3% working solution was prepared by diluting the stock with culture medium and the remaining stock was stored at -80 ℃.

Analysis of inflammatory cells in BALF

The trachea was catheterized and perfused with 2 ml PBS. The liquid and cellular fractions of BALF were separated by centrifugation at 439 x g (2200 rpm) for 10 min at 4 ℃ (Combi R515 centrifuge, Hanil Science, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The cell pellet was suspended in PBS, seeded onto a slide, and stained with Diff-Quick (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). The number of inflammatory cells in BALF on each slide was counted under a light microscope.

Histological analysis

After ligating the right main bronchus, the left lung was inflated at a constant pressure of 15 cm H2O with 0.5% low melting-point agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The left lung tissue was sectioned and fixed in 10% formalin for further histological examination. Section (5 μm) of paraffin-embedded lung tissue were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Emphysematous changes were assessed by measuring the mean linear intercept (MLI) [42], which is a measurement of the mean interalveolar septal wall distance determined by the number of interruptions in 1 mm alveolar wall lines. Four lines were drawn in each field, and each mouse was examined in at least five random fields.

TUNEL assay

End labeling of exposed 3′-OH ends of DNA fragments in paraffin-embedded lung tissue was performed using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) DeadEnd Colorimetric kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Cell nuclei were counterstained with Methyl Green (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Slides were mounted with mounting medium (HIGHDEF IHC fluoromount, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and examined under a light microscope at 400X magnification. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was assessed in 10 random fields per mouse. Among the total nuclei, the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was counted for each image, and a mean was calculated for each mouse.

Cell culture and treatment

Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B, #CRL-9609) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Welgene) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Confluent cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin and 0.05% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 min, and aliquots were subcultured. BEAS-2B cells were treated with concentrations of 20 µg/ml and 3% for PM2.5 and CSE, respectively, for 24 h to assess the effects of the caspase-1 inhibitor VX765 (20 µM; S2228, Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) and the siRNA (40 nM; si-NLRP3, 5′-CAUCAUUCCCGCUAUCUUUTT − 3′ and 60 nM; si-Caspase-1, 5′-GAG GAA AUU UUC CGC AAG G -3′,Bioneer, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). BEAS-2B cells were transfected with si-NLRP3 or si-Caspase-1 using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Transfection efficiency was determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot. The working concentrations of PM2.5 and CSE solutions were based on preliminary experiments (Fig. S2). Beas-2B cells were exposed to various concentrations of PM2.5 (5, 25, and 100 µg/ml) and CSE (0.5, 1, 3, and 5%) solutions. Subsequently, the cells were treated with combined PM2.5 and CSE solutions, including 3% CSE, 3% CSE + PM2.5 10 µg/ml, 3% CSE + PM2.5 20 µg/ml, 5% CSE, 5% CSE + PM2.5 20 µg/ml, PM2.5 10 µg/ml, and PM2.5 20 µg/ml. Notably, cells treated with 3% CSE + PM2.5 20 µg/ml exhibited marked cytotoxicity compared with those treated with 3% CSE alone, thus establishing it as the selected working concentration.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. BEAS-2B cells were seeded in a 96-well culture plate at a density of 5 × 103/well and then treated with PM2.5 and CSE for 24 h. 20 µl of MTT (at a concentration of 5 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the cells were incubated for 2 h in a humidified incubator. 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added after discarding the supernatant to dissolve the formazan, and the optical density at 570 nm (OD570nm) was measured. The viability of the untreated cells (control) was defined as 100%, and the cell viability of all other groups was calculated separately from that of the control group.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay and cytokine measurement

An LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (EZ-CYTOX, DoGenBio, Seoul, Republic of Korea) was used to examine the LDH release level, and the optical density of samples was measured at 490 nm. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in BALF and IL-6 and IL-8 levels in cell supernatant were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Western blot analysis

BEAS-2B cells were treated under different conditions. The total protein was extracted from the cells using RIPA buffer (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (1 µg/ml Aprotinin, 1 µg/ml Leupeptin, 200 µM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM Na3VO4). Then, the total protein was separated and transferred to membranes. The membranes were incubated with 5% non-fat milk and specific antibodies against NLRP3 (1:1000; ab263899, Abcam), caspase-1 (1:1000; ab207802, Abcam), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:1000; 2118, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Finally, the proteins were visualized using ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) or X-ray film in a darkroom.

qRT-PCR

Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to extract total RNA from lung tissue and BEAS-2B cells. Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA. The amount of mRNA was quantified using Advanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix kit and the CFX Connect real-time PCR system (Biorad, Hercules, California, USA). All experiments were performed in duplicate. The following primers were used in lung tissues: tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, IL-33, IFN-γ, and 18 S. The following primers were used in BEAS-2B cells: IL-6, IL-8, NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, IL-18, caspase-3, caspase-7, HMGB1, caspase-8, RIPK3, and GAPDH. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table. 1. The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to 18 S or GAPDH as an endogenous control gene. The relative changes were calculated using the Eq. 2−ΔΔCt.

Statistical analysis

Clinical data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). The relationships between PM2.5 concentration level and clinical parameters were evaluated using linear regression in R Statistical Software (version 4.0.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For all variables, the experimental results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, and Student’s t-test for two groups using GraphPad Prism software (Version 5.01, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was accepted for p-value < 0.05.

Results

Ambient PM2.5 deteriorated quality of life (QOL) in currently smoking patients with COPD

We evaluated the relationship between PM2.5 exposure levels and clinical parameters to determine the effects of cigarette smoking and PM2.5 exposure in patients with COPD. A total of 105 patients were included in the study with 23 (21.9%) of them being current smokers. Their mean age was 68.2 ± 7.2 years, and 97 (92.4%) were male. The mean post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s was 1.6 ± 0.6 L, representing 53.9 ± 16.5% of the predicted value. Mean baseline SGRQ-C score was 37.5 ± 21.8, and 41 patients (39.0%) had a history of acute exacerbation. The mean outdoor and indoor PM2.5 concentration were 17.2 ± 5.0 µg/m3 and 16.2 ± 8.4 µg/m3, respectively (Table 1).

The SGRQ-C score significantly correlated with the PM2.5 exposure level in the days preceding the assessment in currently smoking patients. However, there was no correlation between SGRQ-C score and PM2.5 exposure level in non-smoking patients (Fig. 1A). Regardless of smoking status, there was no significant correlation between the number of acute exacerbations and the PM2.5 exposure level (Fig. 1B), although a slightly higher correlation was noted in current smokers. These results suggest that exposure to ambient PM2.5 deteriorates QOL and may worsen prognosis in currently smoking patients with COPD. To investigate the underlying mechanisms, we performed subsequent in vivo and in vitro experiments.

Correlation between clinical outcomes and actual PM2.5 exposure levels in the days preceding the evaluation. (A) SGRQ-C scores. (B) Number of acute exacerbations. The significance is determined by linear regression. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. SGRQ-C, Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD

Smoking and PM2.5 exposure induced lung injury and increased inflammation in vivo

To investigate the histological changes induced by cigarette smoking and PM2.5 separately or together, experimental mice were classified into four groups: control, smoking, PM2.5, and smoking and PM2.5 combination (Fig. 2A). H&E-stained lung tissue slides from each group revealed that combined exposure to cigarette smoke and PM2.5 resulted in greater peribronchial infiltration of inflammatory cells and greater alveolar destruction compared with those observed in separate exposure to cigarette smoke or PM2.5 (Fig. 2B). The lymphocytes and neutrophils infiltration was reduced in the BALF of PM2.5 exposed mice compared with that of the smoking exposed mice; however, the combined exposure to smoking and PM2.5 resulted in greater infiltration of these cells (Fig. 2C).

Smoking and PM2.5 triggered lung injury and increased inflammation. (A) Timeline of COPD model and PM2.5 treatment. (B) Representative H&E stained lung tissue from mice in control, smoking, PM2.5, and smoking with PM2.5 groups (100X original magnification, scale bar = 500 μm). The upper images show peribronchial inflammatory cell infiltration. The lower images show alveolar destruction. The MLI of lung tissue samples from each group (n = 4 control mice, n = 4 SM mice, n = 5 PM mice, and n = 8 SMPM mice). (C) Total number of cells in the BALF infiltrating the airways. Differential cell numbers of BALF in each group (n = 4 control mice, n = 4 SM mice, n = 6 PM mice, and n = 4 SMPM mice). (D) Levels of cytokines IL-6 and IFN-γ in BALF determined by ELISA (n = 4 control mice, n = 4 SM mice, n = 4 PM mice, and n = 5 SMPM mice). (E) The relative mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, IL-33, and IFN-γ in lung tissues (n = 4 control mice, n = 4 SM mice, n = 6 PM mice, and n = 5 SMPM mice). (F) Representative TUNEL images of lung tissue of mice and TUNEL score (%) of each group (n = 4 control mice, n = 4 SM mice, n = 5 PM mice, and n = 6 SMPM mice, 400X original magnification, scale bar = 100 μm). (G) NLRP3 expression levels in lung tissue of mice (n = 3 control mice, n = 3 SM mice, n = 4 PM mice, and n = 4 SMPM mice. The data are represented as mean ± SD. The significance is determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin; MLI, Mean linear intercept; SD, standard deviation; CTL, control; SM, smoking; PM, PM2.5; SMPM, smoking and PM2.5

The levels of cytokines, such as IL-6 and IFN-γ, were significantly increased in the BALF of mice exposed to a combination of smoking and PM2.5 compared with those of the control (Fig. 2D) [43, 44]. Moreover, the mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-18, and IL-33, was significantly increased in the smoking and PM2.5 combination group compared with those in the control group (Fig. 2E).

Next, we determined whether the combination of cigarette smoke and PM2.5 would affect cell death response compared with exposure to cigarette smoke or PM2.5 separately. Cell apoptosis was most prominent in the smoking and PM2.5 combination group (Fig. 2F). To evaluate other types of cell death, such as pyroptosis, we assessed NLRP3 expression levels using western blotting. NLRP3 expression was significantly upregulated in the smoking group compared with that in the control, but not upregulated in the PM2.5 group; moreover, it peaked in the smoking and PM2.5 combination group (Fig. 2G).

PM2.5 aggravated CSE-induced inflammation in BEAS-2B cells

BEAS-2B cell viability was assessed to determine whether CSE and PM2.5 induce inflammatory reaction and cell death in cell lines. The MTT assay showed that CSE or PM2.5 alone inhibited the proliferation of BEAS-2B cells compared with that in control (Fig. 3A). Next, we determined whether the decreased cell viability was related to inflammasome-induced pyroptosis. In a subsequent experiment, pyroptotic cell death was evaluated by measuring LDH release [45]. The combination of CSE and PM2.5 significantly increased LDH release compared with that in the CSE or PM2.5 group (Fig. 3B).

PM2.5 aggravated cigarette smoke extract-induced inflammation in BEAS-2B cells. (A) PM2.5 and cigarette smoke extract decreased cell viability. (B) PM2.5 and cigarette smoke extract increased LDH release. (C) PM2.5 and cigarette smoke extract enhanced the release of IL-6 and IL-8 in the cell supernatant. (D) Relative mRNA expression level of IL-6 and IL-8. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). The significance is determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. CTL, control; CSE, cigarette smoke extract; PM, PM2.5; CSE + PM, cigarette smoke extract and PM2.5

The IL-6 and IL-8 levels in the cell culture supernatants were then assessed by ELISA. CSE or PM2.5 alone upregulated inflammation in BEAS-2B cells, whereas the combination of CSE and PM2.5 significantly increased both cytokine levels compared with that in CSE or PM2.5 alone (Fig. 3C). To confirm our findings, we measured the transcriptional levels of these cytokines at different exposure levels using qRT-PCR, and the results were consistent with those assessed by ELISA (Fig. 3D).

PM2.5 and CSE exposure upregulated pyroptosis-related genes expression

BEAS-2B cells were exposed to CSE and PM2.5 for 24 h to elucidate the mechanism underlying their inducibility to inflammation and cell death. The transcriptional levels of pyroptosis-related genes, such as NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18, were significantly upregulated in the CSE group compared with those in the control, but they were not upregulated in the PM2.5 group; moreover, the expression of pyroptosis-related genes peaked in the CSE and PM2.5 combination group (Fig. 4A-D).

Exposure to PM2.5 and cigarette smoke extract upregulated expression of pyroptosis-related genes in BEAS-2B cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression level of NLRP3. (B) Relative mRNA expression level of Caspase-1. (C) Relative mRNA expression level of IL-1β. (D) Relative mRNA expression level of IL-18. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). The significance is determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

We determined whether CSE and PM2.5 were also associated with apoptosis- or necrosis-related gene expression. When we compared the mRNA expression levels of the apoptosis-related genes such as caspase-3 and caspase-7, we found that caspase-3 expression was elevated in the CSE and CSE and PM2.5 combination groups compared with that in the control, whereas no difference in the expression of caspase-7 was observed (Fig. S3A). When comparing the mRNA expression levels of necrosis-related genes, such as HMGB1, caspase-8, and RIPK3, no significant difference between groups was observed (Fig. S3B).

These results demonstrated that exposure to the combination of CSE and PM2.5 could decrease BEAS-2B cell viability while increasing inflammation by inducing pyroptosis. Therefore, subsequent studies were conducted to determine how the combination of CSE and PM2.5 induces pyroptosis.

PM2.5 and CSE induce pyroptosis via the NLRP3 inflammasome

We evaluated the interaction between NLRP3 and caspase-1 to determine the role of NLRP3 in the activation of caspase-1 by CSE and PM2.5 exposure. After treating BEAS-2B cells with CSE and PM2.5, western blotting was performed to assess the protein expression level of NLRP3. Exposure to the combination of CSE and PM2.5 increased NLRP3 expression (Fig. 5A).

NLRP3 is necessary for CSE and PM2.5 induced pyroptosis. (A) NLRP3 expression levels in BEAS-2B cells after treatment with CSE and PM2.5. (B) Transfection with siNLRP3 decreased the protein and mRNA levels of NLRP3. (C) Transfection with siNLRP3 decreased the protein and mRNA levels of activated caspase-1. (D) Inhibition of caspase-1 decreased mRNA levels of IL-1β and IL-18. (E) Silencing of NLRP3 significantly increased cell viability. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 2 B and C, n = 3 D, n = 4 E) from three independent experiments. The significance is determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. As for (E), the significance is displayed only between siNC and siNLRP3 for each group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. NC, negative control

BEAS-2B cells were transfected with siNLRP3 to confirm the role of NLRP3 in the combined exposure to CSE and PM2.5. Compared with transfection with the siRNA negative control (siNC), transfection with siNLRP3 reduced NLRP3 protein and mRNA expression, both with and without CSE and PM2.5 combination. NLRP3 protein and mRNA levels were significantly lower in the combination of CSE and PM2.5 than in the control group (Fig. 5B). Moreover, transfection with siNLRP3 decreased the relative protein and mRNA expression levels of activated caspase-1 (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, inhibition of caspase-1 decreased the release of IL-1β and IL-18 (Fig. 5D), and cell viability was also restored by siNLRP3 (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrate that exposure to CSE and PM2.5 induces pyroptosis via NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway.

Discussion

In our study, high levels of ambient PM2.5 were associated with higher SGRQ-C scores in currently smoking patients with COPD. Combined exposure to cigarette smoke and PM2.5 was associated with increased inflammatory cell infiltration and inflammatory cytokine release in mouse lung. Exposure to a combination of CSE and PM2.5 reduced cell viability and upregulated pyroptosis-related gene transcription in BEAS-2B cells. NLRP3 silencing with siRNA reduced pyroptosis and restored cell viability. Therefore, PM2.5 aggravates smoking-induced airway inflammation and cell death via pyroptosis.

Cigarette smoke-induced airway epithelial damage is reported to induce airway remodeling, resulting in COPD [46, 47]. The epithelial changes in COPD are varied, including Goblet cell metaplasia, squamous metaplasia, and basal membrane thickening [48,49,50]. Previous studies demonstrated cigarette smoke-induced damage on bronchial or tracheal epithelial cells, including impaired epithelial barrier function, cilia toxicity, and mucus hypersecretion [51,52,53,54]. Recently, cigarette smoking-induced changes in human circulating cells were reported, including increased circulating leukocytes and neutrophils, upregulated myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and activated natural killer cells [55,56,57].

There is growing evidence that PM2.5 exposure is associated with the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells in lung. Exposure to PM2.5 significantly increased inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages, as well as inflammatory cytokines in BALF [14, 15, 27]. Moreover, exposure to PM2.5 was associated with alveolar destruction, septal thickening, emphysematous changes, airway remodeling, and inflammatory cell infiltration [27, 28]. Exposure to PM2.5 and cigarette smoke has been reported to aggravate inflammation and structural changes in the lungs [28, 29]. In our experiment, there was a significant increase in inflammatory cells and cytokines in the BALF supernatant, as well as an increase in MLI and TUNEL-positive cells and marked emphysematous changes in the lung tissue of mice exposed to both PM2.5 and cigarette smoke. These findings suggest that PM2.5 exposure could aggravate cigarette smoking-induced airway inflammation and structural destruction in the lungs of patients with COPD. Moreover, PM exposure is also associated with altered immune cell phenotype [58, 59] and immunosuppressive lung microenvironment, which is highly populated by tolerogenic dendritic cells, macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [60]. Further studies are needed on PM-induced non-inflammatory lung injury.

Previously, the Wnt5a–ERK pathway was proposed as a mechanism whereby PM2.5 could aggravate smoking-induced airway inflammation [29]. Meanwhile, our data revealed that the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β and IL-18 were elevated in the lung tissue of mice; thus, we could infer that pyroptosis may contribute to inflammation and lung injury caused by PM2.5 and cigarette smoking [24, 25, 27]. Pyroptosis is a kind of programmed cell death induced by inflammasomes [18, 19]. Among the inflammasomes, NLRP3 is known to be critical in recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns or damage-associated molecular patterns [21, 22]. Activated NLRP3 inflammasome triggers cleavage of pro-caspase-1, resulting in cleaved caspase-1. Thereafter, activated caspase-1 increases IL-1β and IL-18 and cleaves gasdermin D, leading to pyroptosis [24, 25, 61, 62]. Our findings supported the role of pyroptosis by demonstrating that the exposure to both PM2.5 and CSE decreased cell viability while upregulating transcription of NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18 in BEAS-2B cells. Moreover, siRNA-mediated NLRP3 gene silencing decreased both NLRP3 and caspase-1 levels while restoring cell viability. These findings suggest that both PM2.5 and CSE induce pyroptosis via the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway. Furthermore, inactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome could be a novel therapeutic target in COPD [24, 27, 63].

In our experiments, inflammatory and pyroptotic markers in in vivo and in vitro experiments were increased with cigarette smoke exposure, but not with PM2.5 alone. These markers were increased further with combined cigarette smoke and PM2.5 exposure. Therefore, our experiments suggest that cigarette smoke, compared with PM2.5, has a major impact on airway inflammation and pyroptotic cell death, and PM2.5 exposure could potentiate cigarette smoking-induced inflammatory reaction. This effects of combined exposure with smoking and PM2.5 also showed similar trends for the development of COPD clinically [64].

Higher ambient PM2.5 concentrations have recently been linked to an increased prevalence of COPD, lung function decline, and mortality [7,8,9,10]. PM2.5 and current cigarette smoking status have been suggested to have an additive effect on the risk of COPD [64]. Moreover, ambient PM2.5 exposure has been linked to severe respiratory symptoms and a decline in lung function, resulting in deteriorated QOL in patients with COPD [65, 66]. Previously, it was reported that biomass smoke exposure was associated with the airway-predominant phenotype of COPD, resulting in more air trapping, severe respiratory symptoms, and deteriorated QOL compared with smoking-related COPD of emphysema-predominant phenotype [67]. Exposure to PM2.5 was associated with systemic inflammation in patients with COPD [68], and systemic inflammation in COPD was associated with poor QOL [69, 70]. In pyroptosis, the plasma-membrane rapidly ruptures and proinflammatory intracellular contents are released, resulting in pathological inflammation [19]. Moreover, patients with stable COPD had significantly higher plasma IL-1β levels and upregulated expression of the IL1B, NLRP3, and CASP1 genes compared with that in healthy controls [71]. In our investigation, high ambient PM2.5 concentrations were linked to high SGRQ-C scores in currently smoking patients with COPD. Moreover, high SGRQ-C scores were associated with rapid lung function decline and frequent exacerbation [72,73,74]. We can conclude from this study that PM2.5 exposure aggravates smoking-induced airway inflammation and deteriorates QOL of patients with COPD, with local or systemic pyroptosis-mediated inflammation playing an important role. Furthermore, PM2.5 exposure may induce lung function decline and exacerbation in currently smoking patients with COPD.

There are some limitations in our study. First, PM2.5 exposure alone did not alter the total number or the differential proportions of cells in the BALF, nor did it induce peribronchial inflammatory cell infiltration. Second, a 1-week time interval between the last exposure to PM2.5 and euthanasia of the mice may allow clearance of PM2.5 by macrophages. Third, the synergistic effect of PM2.5 and cigarette smoke exposure was prominent in the protein composition of BALF, whereas this synergy was relatively less evident in qPCR levels of lung homogenate. Since both PM2.5 and cigarette smoke were delivered intratracheally, their impact on the alveolar space appears to be more pronounced. Additionally, the alterations observed in protein levels holds greater significance compared with those observed in mRNA. Fourth, although exposure to smoking and PM2.5 caused lung injury and cell death in our experiments, other cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis, might be involved. Meanwhile, our results demonstrate a significant upregulation of pyroptosis-related genes and proteins, as well as restored cell viability with caspase-1 inhibition and NLRP3 silencing. Fifth, in clinical data, a larger sample size and longer study duration might show a more consistent difference in associations between current and ex-smokers. However, the correlation between SGRQ-C score and PM2.5 concentration in current smokers implies that the combined exposure to smoking and PM2.5 has an additive aggravating effect, and pyroptosis-induced systematic inflammation may be involved.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the combined exposure to PM2.5 and cigarette smoking aggravates smoking-induced airway inflammation and cell death with pyroptosis being one of the dominant mechanisms. In patients with COPD, PM2.5 aggravates the QOL caused by concurrent smoking and may deteriorate lung function and induce exacerbation. COPD is a preventable disease caused by exposure to noxious particles with various synergistic effects. Identifying these addictive effects will contribute to our understanding of the pathogenesis of COPD and the development of effective treatment options.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CSE:

-

Cigarette smoke extract

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GADPH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- IFN:

-

Interferon, IL: Interleukin

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MLI:

-

Mean linear intercept

- MTT:

-

3-[4,5-imethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NLR:

-

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor

- NLRP3:

-

NLR protein-3

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PM2.5 :

-

Particulate matter of diameter ≤ 2.5 μm

- PMSF:

-

Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SGRQ-C:

-

Saint George’s respiratory questionnaire specific for COPD

- TUNEL:

-

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

References

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Chen R, Decramer M, Fabbri LM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–82.

Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gudmundsson G, Welte T, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Studnicka M, Bateman E, Anto JM, Burney P, et al. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based burden of obstructive lung disease study. Chest. 2011;139:752–63.

Tan WC, Sin DD, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Chapman KR, Cowie R, FitzGerald JM, Marciniuk DD, Maltais F, Buist AS, et al. Characteristics of COPD in never-smokers and ever-smokers in the general population: results from the CanCOLD study. Thorax. 2015;70:822–9.

Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–43.

Paulin LM, Diette GB, Blanc PD, Putcha N, Eisner MD, Kanner RE, Belli AJ, Christenson S, Tashkin DP, Han M, et al. Occupational exposures are associated with worse morbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:557–65.

Gan WQ, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C, Sadatsafavi M, Brauer M. Associations of ambient air pollution with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalization and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:721–7.

Liu S, Zhou Y, Liu S, Chen X, Zou W, Zhao D, Li X, Pu J, Huang L, Chen J, et al. Association between exposure to ambient particulate matter and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a cross-sectional study in China. Thorax. 2017;72:788–95.

Lamichhane DK, Leem JH, Kim HC. Associations between Ambient Particulate Matter and Nitrogen Dioxide and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary diseases in adults and effect modification by demographic and lifestyle factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15.

Dai L, Zanobetti A, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD. Associations of fine particulate matter species with mortality in the United States: a multicity time-series analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:837–42.

Doiron D, de Hoogh K, Probst-Hensch N, Fortier I, Cai Y, De Matteis S, Hansell AL. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur Respir J 2019, 54.

Xue H, Li MX. MicroRNA-150 protects against cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation and airway epithelial cell apoptosis through repressing p53: MicroRNA-150 in CS-induced lung inflammation. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2018;37:920–8.

Pan X, Xu K, Li Y, Wang X, Peng X, Li M, Li Y. Interleukin-35 expression protects against cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:727–32.

Li C, Chen J, Yuan W, Zhang W, Chen H, Tan H. Preventive effect of ursolic acid derivative on particulate matter 2.5-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease involves suppression of lung inflammation. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:632–40.

Ogino K, Nagaoka K, Okuda T, Oka A, Kubo M, Eguchi E, Fujikura Y. PM2.5-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in NC/Nga mice. Environ Toxicol. 2017;32:1047–54.

Zheng R, Tao L, Jian H, Chang Y, Cheng Y, Feng Y, Zhang H. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and lung fibrosis caused by airborne fine particulate matter. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;163:612–9.

Vij N, Chandramani-Shivalingappa P, Van Westphal C, Hole R, Bodas M. Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy impairment accelerates lung aging, COPD-emphysema exacerbations and pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;314:C73–87.

Wang Y, Zhong Y, Liao J, Wang G. PM2.5-related cell death patterns. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:1024–9.

Miao EA, Rajan JV, Aderem A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptotic cell death. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:206–14.

Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:99–109.

Rathinam VA, Fitzgerald KA. Inflammasome complexes: emerging mechanisms and Effector functions. Cell. 2016;165:792–800.

Barbe F, Douglas T, Saleh M. Advances in nod-like receptors (NLR) biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:681–97.

Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:397–411.

Nachmias N, Langier S, Brzezinski RY, Siterman M, Stark M, Etkin S, Avriel A, Schwarz Y, Shenhar-Tsarfaty S, Bar-Shai A. NLRP3 inflammasome activity is upregulated in an in-vitro model of COPD exacerbation. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0214622.

Zhang MY, Jiang YX, Yang YC, Liu JY, Huo C, Ji XL, Qu YQ. Cigarette smoke extract induces pyroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells through the ROS/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway. Life Sci. 2021;269:119090.

Xiong R, Jiang W, Li N, Liu B, He R, Wang B, Geng Q. PM2.5-induced lung injury is attenuated in macrophage-specific NLRP3 deficient mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;221:112433.

Li J, An Z, Song J, Du J, Zhang L, Jiang J, Ma Y, Wang C, Zhang J, Wu W. Fine particulate matter-induced lung in fl ammation is mediated by pyroptosis in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;219:112351.

Jia H, Liu Y, Guo D, He W, Zhao L, Xia S. PM2.5-induced pulmonary inflammation via activating of the NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway. Environ Toxicol. 2021;36:298–307.

Zhao J, Li M, Wang Z, Chen J, Zhao J, Xu Y, Wei X, Wang J, Xie J. Role of PM2.5 in the development and progression of COPD and its mechanisms. Respir Res. 2019;20:120.

Wang Z, Zhao J, Wang T, Du X, Xie J. Fine-particulate matter aggravates cigarette smoke extract-induced airway inflammation via Wnt5a-ERK pathway in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:979–94.

Park S, Ra SW, Kang SY, Kim HC, Lee SW. Effect of particulate matter exposure on patients with COPD and risk reduction through behavioural interventions: the protocol of a prospective panel study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e039394.

Kim H, Na G, Park S, Ra SW, Kang SY, Kim HC, Kim HC, Lee SW. The impact of life behavior and environment on particulate matter in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ Res. 2021;198:111265.

Huh J-Y, Kim H, Na G, Park S, Ra SW, Kang S-Y, Kim HC, Kim H-C, Lee SW. Effects of outdoors and indoors particulate matter 2.5 on COPD: Multicenter prospective observational study. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:PA1788.

Sun B, Shi Y, Li Y, Jiang J, Liang S, Duan J, Sun Z. Short-term PM(2.5) exposure induces sustained pulmonary fibrosis development during post-exposure period in rats. J Hazard Mater. 2020;385:121566.

Kim KH, Park TS, Kim YS, Lee JS, Oh YM, Lee SD, Lee SW. Resolvin D1 prevents smoking-induced emphysema and promotes lung tissue regeneration. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1119–28.

Huh JW, Kim SY, Lee JH, Lee JS, Van Ta Q, Kim M, Oh YM, Lee YS, Lee SD. Bone marrow cells repair cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L255–266.

Lee SH, Kim J, Kim NH, Kim OH, Shon CH, Kim SJ, Jang Y, Yun S, Lim SE, Jung SY, et al. Gut microbiota composition and metabolite profiling in smokers: a comparative study between emphysema and asymptomatic individuals with therapeutic implications. Thorax. 2023;78:1080–9.

Jang YO, Kim OH, Kim SJ, Lee SH, Yun S, Lim SE, Yoo HJ, Shin Y, Lee SW. High-fiber diets attenuate emphysema development via modulation of gut microbiota and metabolism. Sci Rep. 2021;11:7008.

Jang YO, Lee SH, Choi JJ, Kim DH, Choi JM, Kang MJ, Oh YM, Park YJ, Shin Y, Lee SW. Fecal microbial transplantation and a high fiber diet attenuates emphysema development by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1128–39.

Kang MJ, Lee CG, Lee JY, Dela Cruz CS, Chen ZJ, Enelow R, Elias JA. Cigarette smoke selectively enhances viral PAMP- and virus-induced pulmonary innate immune and remodeling responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2771–84.

Charoud-Got J, Emma G, Seghers J, Tumba-Tshilumba MF, Santoro A, Held A, Snell J, Emteborg H. Preparation of a PM2.5-like reference material in sufficient quantities for accurate monitoring of anions and cations in fine atmospheric dust. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409:7121–31.

Richter A, O’Donnell RA, Powell RM, Sanders MW, Holgate ST, Djukanovic R, Davies DE. Autocrine ligands for the epidermal growth factor receptor mediate interleukin-8 release from bronchial epithelial cells in response to cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:85–90.

Knudsen L, Weibel ER, Gundersen HJ, Weinstein FV, Ochs M. Assessment of air space size characteristics by intercept (chord) measurement: an accurate and efficient stereological approach. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010;108:412–21.

Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:631–8.

Rincon M, Irvin CG. Role of IL-6 in asthma and other inflammatory pulmonary diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1281–90.

Wu X, Zhang H, Qi W, Zhang Y, Li J, Li Z, Lin Y, Bai X, Liu X, Chen X, et al. Nicotine promotes atherosclerosis via ROS-NLRP3-mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:171.

Puchelle E, Zahm JM, Tournier JM, Coraux C. Airway epithelial repair, regeneration, and remodeling after injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:726–33.

Perotin JM, Adam D, Vella-Boucaud J, Delepine G, Sandu S, Jonvel AC, Prevost A, Berthiot G, Pison C, Lebargy F, et al. Delay of airway epithelial wound repair in COPD is associated with airflow obstruction severity. Respir Res. 2014;15:151.

Saetta M, Turato G, Baraldo S, Zanin A, Braccioni F, Mapp CE, Maestrelli P, Cavallesco G, Papi A, Fabbri LM. Goblet cell hyperplasia and epithelial inflammation in peripheral airways of smokers with both symptoms of chronic bronchitis and chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1016–21.

Polosukhin VV, Richmond BW, Du RH, Cates JM, Wu P, Nian H, Massion PP, Ware LB, Lee JW, Kononov AV, et al. Secretory IgA Deficiency in Individual Small Airways is Associated with persistent inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1010–21.

Gohy ST, Hupin C, Fregimilicka C, Detry BR, Bouzin C, Gaide Chevronay H, Lecocq M, Weynand B, Ladjemi MZ, Pierreux CE, et al. Imprinting of the COPD airway epithelium for dedifferentiation and mesenchymal transition. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1258–72.

Heijink IH, Brandenburg SM, Postma DS, van Oosterhout AJ. Cigarette smoke impairs airway epithelial barrier function and cell-cell contact recovery. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:419–28.

Tatsuta M, Kan OK, Ishii Y, Yamamoto N, Ogawa T, Fukuyama S, Ogawa A, Fujita A, Nakanishi Y, Matsumoto K. Effects of cigarette smoke on barrier function and tight junction proteins in the bronchial epithelium: protective role of cathelicidin LL-37. Respir Res. 2019;20:251.

Aufderheide M, Scheffler S, Ito S, Ishikawa S, Emura M. Ciliatoxicity in human primary bronchiolar epithelial cells after repeated exposure at the air-liquid interface with native mainstream smoke of K3R4F cigarettes with and without charcoal filter. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2015;67:407–11.

Yu Q, Chen X, Fang X, Chen Q, Hu C. Caveolin-1 aggravates cigarette smoke extract-induced MUC5AC secretion in human airway epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:1435–42.

Andreoli C, Bassi A, Gregg EO, Nunziata A, Puntoni R, Corsini E. Effects of cigarette smoking on circulating leukocytes and plasma cytokines in monozygotic twins. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:57–64.

Scrimini S, Pons J, Agusti A, Soriano JB, Cosio BG, Torrecilla JA, Nunez B, Cordova R, Iglesias A, Jahn A, et al. Differential effects of smoking and COPD upon circulating myeloid derived suppressor cells. Respir Med. 2013;107:1895–903.

Wang J, Urbanowicz RA, Tighe PJ, Todd I, Corne JM, Fairclough LC. Differential activation of killer cells in the circulation and the lung: a study of current smoking status and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58556.

De Falco G, Terlizzi M, Sirignano M, Commodo M, D’Anna A, Aquino RP, Pinto A, Sorrentino R. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from smokers release higher levels of IL-1-like cytokines after exposure to combustion-generated ultrafine particles. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43016.

De Falco G, Colarusso C, Terlizzi M, Popolo A, Pecoraro M, Commodo M, Minutolo P, Sirignano M, D’Anna A, Aquino RP, et al. Chronic obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Derived circulating cells release IL-18 and IL-33 under Ultrafine Particulate Matter exposure in a Caspase-1/8-Independent manner. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1415.

Colarusso C, De Falco G, Terlizzi M, Roviezzo F, Cerqua I, Sirignano M, Cirino G, Aquino RP, Pinto A, D’Anna A, Sorrentino R. The inhibition of Caspase-1- does not revert particulate matter (PM)-Induced Lung Immunesuppression in mice. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1329.

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660–5.

Liu J, Fan G, Tao N, Sun T. Role of Pyroptosis in respiratory diseases and its therapeutic potential. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:2033–50.

Wang L, Chen Q, Yu Q, Xiao J, Zhao H. TREM-1 aggravates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease development via activation NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Inflamm Res. 2021;70:971–80.

Su J, Ye Q, Zhang D, Zhou J, Tao R, Ding Z, Lu G, Liu J, Xu F. Joint association of cigarette smoking and PM2.5 with COPD among urban and rural adults in regional China. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21:87.

Nakao M, Ishihara Y, Kim CH, Hyun IG. The impact of Air Pollution, including Asian sand dust, on respiratory symptoms and health-related quality of life in outpatients with chronic respiratory disease in Korea: a panel study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2018;51:130–9.

Cortez-Lugo M, Ramirez-Aguilar M, Perez-Padilla R, Sansores-Martinez R, Ramirez-Venegas A, Barraza-Villarreal A. Effect of personal exposure to PM2.5 on Respiratory Health in a Mexican panel of patients with COPD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:10635–47.

Camp PG, Ramirez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, Alva LF, McDougall JE, Sin DD, Pare PD, Muller NL, Silva CI, Rojas CE, Coxson HO. COPD phenotypes in biomass smoke- versus tobacco smoke-exposed Mexican women. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:725–34.

Chen X, Que C, Yao Y, Han Y, Zhang H, Li X, Lu X, Chen W, Hu X, Wu Y, et al. Susceptibility of individuals with lung dysfunction to systemic inflammation associated with ambient fine particle exposure: a panel study in Beijing. Sci Total Environ. 2021;788:147760.

Garrod R, Marshall J, Barley E, Fredericks S, Hagan G. The relationship between inflammatory markers and disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:236–40.

Agusti A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, MacNee W, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, Vestbo J, Lomas DA, Calverley PM, Wouters E, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37483.

Markelic I, Hlapcic I, Ceri A, Radic Antolic M, Samarzija M, Popovic-Grle S, Vukic Dugac A, Rumora L. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7544.

Rehman AU, Shah S, Abbas G, Harun SN, Shakeel S, Hussain R, Hassali MAA, Rasool MF. Assessment of risk factors responsible for rapid deterioration of lung function over a period of one year in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13578.

Kim JK, Lee SH, Lee BH, Lee CY, Kim do J, Min KH, Kim SK, Yoo KH, Jung KS, Hwang YI. Factors associated with exacerbation in mild- to-moderate COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1327–33.

Mackay AJ, Kostikas K, Roche N, Frent SM, Olsson P, Pfister P, Gupta P, Patalano F, Banerji D, Wedzicha JA. Impact of baseline symptoms and health status on COPD exacerbations in the FLAME study. Respir Res. 2020;21:93.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sun-Hee Heo (Asan Medical Center), Shinhee Park (Gangneung Asan Hospital), Seung Won Ra (Ulsan University Hospital), and Sung-Yoon Kang (Gachon University Gil Medical Center) for their help with data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the research of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [No. 2019ER671100 and 01, and 2021ER120900], the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) Research Initiative Program (YJP & SJL), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2023R1A2C2006688 and RS-2023-00222687, SWL), the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022M3A9G8017220), Republic of Korea, and Medical Research Promotion Program through the Gangneung Asan Hospital funded by the Asan Foundation (2023II0003). The funder did not have any role in the design of the study and did not have any role in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC, SYP, and SWL conceived and designed the study. SYP, J-YH, NHK, CHS, EYO, Y-JP, S-JL, and H-CK performed experiments and collected the data. CC, SYP, J-YH, and SWL analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript. All authors accept responsibility for the accuracy of the content of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Asan Medical Center (approval number 2020-12-342). The previous clinical study was individually approved by the Institutional Review Boards as follows: Asan Medical Center (2019 − 0479), Gangneung Asan Hospital (2019-06-049), Ulsan University Hospital (2019-07-049), and Gachon University Gil Medical Center (GBirb2019-290). All participants were given detailed information about the study and provided written informed consent. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Registration No. NCT04020237). The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the ARRIVE guidelines, and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, C., Park, S.Y., Huh, JY. et al. Fine particulate matter aggravates smoking induced lung injury via NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway in COPD. J Inflamm 21, 13 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-024-00384-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-024-00384-z