Abstract

Background

The population structure and the correlation between antimicrobial resistance (AMR) phenotypes and genotypes in Aeromonas species isolated from patients with gastroenteritis are not well understood. The aims of the study were to: (1) investigate the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Aeromonas species isolated from patients with gastroenteritis; (2) explore the relationship between AMR genes and resistance phenotypes; and (3) describe the population structure of these isolates and provide evidence of transmission events among them.

Methods

This microbiological survey was performed at the Microbiology Laboratory of the Emek Medical Center in Afula, Israel. Cultivation of Aeromonas was attempted from stool samples that tested positive by PCR. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed using the Sensititre GN3F microdilution panel. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) was done using the Illumina NextSeq500/550 system. Phylogenetic studies involved multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and core genome (cg) MLST. Resistance mechanisms were identified using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database and compared with the AST results.

Results

The study included 67 patient-unique isolates. The species that were identified included A. caviae (n = 58), A. dhakensis (n = 3), A. media (n = 2), A. veronii (n = 2) and A. hydrophila (n = 2). Isolates were almost uniformly susceptible to amikacin, gentamicin, aztreonam, cefepime, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin and meropenem. All isolates with the exception of 1–2 isolates were resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin and ampicillin-sulbactam which was compatible with the presence of the blaOXA genes. Variable resistance rates were observed to cefuroxime, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, piperacillin-tazobactam that were not correlated with the presence of other β-lactamase genes. Resistance to tetracycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole correlated with the presence of tetA and sul1, respectively. The population structure of A. caviae was highly diverse with the minority of the isolates (16/57) clustering into six defined sequence types. A cgMLST-based distance of four genes was found in one pair of isolates, suggesting common source transmission.

Conclusions

A. caviae is the dominant species related to gastroenteritis and is characterized by a diverse population structure, with almost no evidence for common-source transmission. Resistance rates to most antimicrobial agents were low and partially matched with the presence of resistance genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aeromonas species are capable of causing a variety of different infections, including gastro-intestinal and extraintestinal infections [1]. Defining the precise role of Aeromonas species in causing gastroenteritis (GE) proves challenging, particularly outside of isolated outbreaks. This challenge arises from the variability in clinical symptoms, the absence of a specific clinical profile, the presence of Aeromonas in asymptomatic individuals [2] and by the frequent isolation of other potential pathogens in the same stool sample [3]. Consequently, Aeromonas species are not consistently included in routine stool sample testing [4] and the available data on these infections remain relatively limited.

A previous study reported the rate of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Aeromonas isolated from stool samples but did not conduct an analysis of resistance mechanisms [4]. A recent study of Aeromonas isolated mainly from hepato-biliary infections did not find a correlation between AMR phenotype and resistance genes [5]. Furthermore, as Aeromonas gastroenteritis is a food-borne infection, understanding the population structure of these infections could aid in deciphering transmission dynamics within the community.

Our laboratory, serving both the hospital and the surrounding community, commenced testing for Aeromonas gastroenteritis in December 2021, providing us with an opportunity to address these questions. Thus, the study aimed to: (1) investigate the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Aeromonas species isolated from patients with gastroenteritis; (2) explore the relationship between AMR genes and resistance phenotypes; and (3) describe the population structure of these isolates and provide evidence of transmission events among them.

Methods

Setup and population

This microbiological survey study was performed at the Microbiology Laboratory of the Emek Medical Center (EMC) in Afula, Israel. The EMC laboratory serves as the regional laboratory for a population of about 0.5 million of Clalit Health Services members, living predominantly in rural settlements and small urban centers.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were performed at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Microbiology laboratory.

Study design

The study was part of a prospective survey of bacterial gastroenteritis conducted between December 2021 until October 2022 [6]. All stool samples submitted to the EMC laboratory underwent PCR testing for Aeromonas according to the routine laboratory protocol. Samples that tested positive for Aeromonas by PCR were then cultured (details below), and one Aeromonas isolate per patient was included in the study.

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the EMC.

Identification and cultivation of Aeromonas from stool samples

Stool samples were transported from the community clinics and were tested daily except on weekends, where part of each sample was suspended in ASL buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and refrigerated at 4 °C until tested by PCR only (culturing was done from the original sample tube). Multiplex PCR for Aeromonas and other bacterial pathogens was performed as previously described [7]. Stool samples that were positive by PCR for Aeromonas were inoculated into alkaline peptone water 0.5 M NaCl with Cephalothin (10 mg/l) and incubated overnight [8] followed by sub-culturing onto SS agar plates (Hylabs, Rehovot, Israel). Presumptive Aeromonas colonies were identified by MALDI Biotyper Sirius system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) using the MBT IVD Library Revision software. Definite determination of species was based on whole genome sequencing as described below.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST)

AST were performed at the EMC laboratory using the Sensititre GN3F microdilution panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. AST included amikacin, ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, aztreonam, cefazolin, cefepime, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, tetracycline, tobramycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT). AST breakpoints were interpreted (when available) in accordance with the CLSI recommendations for Aeromonas species [9] or if absent (including ampicillin-sulbactam, aztreonam, cefazolin, cefepime, cefoxitin, cefuroxime and tobramycin), in accordance with the recommendations to Enterobacterales [10].

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analyses

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) was done using the Illumina NextSeq500/550 system. Libraries were prepared using Illumina DNA Prep (Illumina,20,060,059). The IDT for Illumina DNA/RNA UD Indexes (Illumina, 20,027,213) were used to tagment the DNA libraries for sequencing. After sequencing of each library, FASTQ files were imported into CLC Genomics Workbench version 23.0.5(Qiagen, Denmark). Following sequencing, the reads underwent quality trimming and contigs were assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench version 23 (Qiagen, Denmark), with the following sequences applied as a template: A. caviae NZ_AP022254, A. hydrophila CP000426, A. media CP118939, A. dhakensis CP000462 and A. veronii NZ_LKKE01000001-NZ_LKKD01000048. Identification of resistance mechanisms was conducted through a combined approach, which involved (i) annotating and identifying known acquired antibiotic-resistant genes using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [11], with a cutoffs of 60% identity and 80% coverage; (ii) detection of nonsynonymous mutations of selected genes and examining their correlation with resistance traits using a multi-sequence alignment approach by AliView version 1.27. Identification of protein domain sites was done using the InterProScan software [12], in comparison with A. caviae WP_063864115. Species designation was based on the reported average nucleotide identity. This method involved comparing the genome sequence of the tested isolates with those of reference type strains accessible in the GenBank database [13].

Core genome (cg) multi locus sequence typing (MLST) scheme and phylogenetic analyses

We employed the chewBBACA [14] to develop two distinct whole-genome (wg) sequencing schemas, later refined into core genome (cg) schemas. The first schema encompassed 67 isolates representing five different Aeromonas species, and the second was exclusively tailored to the 58 isolates of A. caviae. Prodigal [15] (version 2.6.3) facilitated the identification of Coding DNA Sequences (CDS) for both schemas, while BLAST+ [16] (version 2.9.0) was used for conducting allelic comparisons. The initial phase involved constructing a wgMLST schema that included all CDS from the isolates, followed by the removal of paralogous alleles to establish the cgMLST schema. During the “CreateSchema” phase, each genome was annotated for pairwise comparisons, leading to an extensive all-against-all BLASTP search. The resulting BLAST score ratio (BSR) was calculated, with genes encoding identical or nearly identical proteins (BSR exceeding 0.6 by default) consolidated into a single database, representing alleles of the same locus.

For the A. caviae-specific schema, a cross-reference with the sequence types from PubMLST was also performed to enhance the contextual understanding of the isolates. The allelic profiles derived from the chewBBACA cgMLST schemas of both groups were then subjected to phylogenetic analysis using GrapeTree software (version 1.5.0). Neighbor Joining (NJ) and Minimum Spanning Trees were constructed for each schema, with the trees generated from the allelic profiles being visualized in iTOL [17]. This comprehensive approach allowed for a detailed exploration of the genetic relationships within and between the diverse Aeromonas spp., with a specific focus on the A. caviae isolates. Two isolates derived from two separate samples of the same patient were included in the analysis. As these two isolates were assumed to be directly related, they were included in order to provide an epidemiological control for the phylogenetic schema, i.e., the number of gene-differences that can be expected to reflect direct epidemiological linkage.

Data availability

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited in NCBI under BioProject accession number PRJNA1040111. In addition, all 58 A. caviae isolates were deposited in PubMLST under ID BIGSdb_20231207071129_2157505_94891.

Statistical analysis

MIC50 and MIC90 were calculated using RStudio software, version 4.1.2. Graphs were drawn using the ggplot2 package in R.

Results

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Aeromonas species

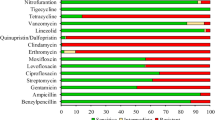

During the study period, Aeromonas species were isolated from 67 patient-unique stool samples and underwent WGS. The distribution of species was as follows: A. caviae (n = 58), A. dhakensis (n = 3), A. madia (n = 2), A. veronii (n = 2) and A. hydrophila (n = 2). Compared with WGS, MALDI-ToF correctly identified 52 of the 67 isolates (77.6%) with all A. dhakensis isolates misidentified as A. hydrophila. A second A. caviae isolate from an additional sample from the same patient was employed as a control for the phylogenetic analysis (see below). The results of the AST of the 58 A. caviae isolates are presented in Fig. 1 and table S1. A. caviae isolates were uniformly susceptible to amikacin, gentamicin, aztreonam and cefepime. Also, with the exception of 1–2 isolates, all were susceptible to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin and meropenem. In contrast, all isolates with the exception of 1–2 isolates were resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin and ampicillin-sulbactam. A more variable distribution of the MIC values was observed with the β-lactam antimicrobials cefuroxime, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone and piperacillin-tazobactam and with tetracycline and SXT.

The MIC distributions of 12 antimicrobials for 58 A. caviae isolates. The red, orange and green dots indicate the resistant, intermediate and susceptible breakpoints, respectively. Black dots were used if no breakpoints were available. MIC50 and MIC90 values are indicated by black dotted and black dashed lines, respectively. Dot/dash lines indicate identical MIC50 and MIC90 values

Similar patterns of antimicrobials susceptibility profiles were observed with the non-caviae Aeromonas species (table S1).

Genotypic analysis of antimicrobial resistance in Aeromonas species

Tetracycline and SXT: The phenotypic-molecular correlations for tetracycline and SXT resistance are presented in Fig. 2a. Resistance to tetracycline was related with the presence of the tet(A) gene, whereas SXT resistance was related to the presence of the sul1 gene. Two susceptible isolate also possessed the sul1 gene but had a relatively elevated MIC compared with the other susceptible isolates (2/38 vs. ≤0.5/9.5, respectively).

β-lactam antimicrobials: The phenotypic-molecular correlations for cefuroxime, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime and piperacillin-tazobactam resistance are presented in Fig. 2b. All A. caviae isolates harbored at least one blaOXA and blaMOX types genes, with the most common alleles being blaOXA−504, blaMOX−12 and blaMOX−13. Six isolates also harbored a second blaOXA gene allele. No correlation was observed between the allele type or the presence of more than one blaOXA gene allele and the presence of resistance to the β-lactam antimicrobials tested. Other blaOXA alleles alone or in addition to the blaOXA−504 gene were present in a 11-isolate phylogenetic cluster.

As mentioned above, almost all isolates were resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin and ampicillin-sulbactam which was compatible with the presence of the blaOXA genes. The single A. caviae isolate that was susceptible to all of these agents harbored both blaOXA−504 and blaMOX−13. Comparative analysis of the blaOXA−504 gene protein sequence identified a S53Y substitution at the enzyme active site.

In species other than A. caviae, all isolates harbored one blaOXA gene of different alleles than A. caviae but only two isolates harbored blaMOX−9. Other β-lactamase that were detected included blacphA, blaceps and blaAQU. As with A. caviae, the presence of the blaOXA gene correlated with the resistance to ampicillin, cefazolin and ampicillin-sulbactam but no correlation was found with the resistance phenotypes to the other β-lactam antimicrobials.

Phylogenetic analysis of Aeromonas caviae isolates

The cgMLST-based phylogenetic analysis of A. caviae isolates is presented in Fig. 3 and S1. The population structure was highly diverse with the minority of the isolates (16/57) clustering into six defined sequence types (ST) (Fig. 3 and S2). Isolates 95,875 and 84,764 were obtained from the same patient and were included in the analysis as control. Both of them were identified as ST-2438 with only 7-gene difference in cgMLST analysis (figure S1). The numbers of cgMLST gene difference between isolates within the same ST were higher in most ST clusters with the exception of two ST-2429 isolates (from two patients), were the cgMLST gene difference was 4 genes.

Discussion

Our study of the molecular features of gastroenteritis-related Aeromonas species was initiated following the transition from culture to PCR-based diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis [6]. Prior to this transition, Aeromonas was not routinely tested in stool cultures in our laboratory (or anywhere in Israel) and thus the species distribution in our community was unknown. The predominant species in our study was A. caviae (58/67), with four other species accounting for the rest of the isolates. A. caviae was also reported as the predominant species (69%) in a previous study of Aeromonas gastroenteritis North-Western Israel [4], followed by A. veronii in 29%. Globally, four species account for most cases of gastroenteritis: A. hydrophila, A. caviae, A. veronii biovar.sobria, and A. trota; A. caviae were the predominant species in most of the reviewed studies [2] We also identified three cases of A. dhakensis, a species that is rarely isolated from stool culture and is typically found in tropical areas [18].

AST results for the dominant species (A. caviae) showed relatively low variability, with the vast majority of isolates being either susceptible (e.g., ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin) or resistant to the tested antimicrobial drugs (e.g., ampicillin, cefazolin). More variability was found in several antimicrobial drugs, such as cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, tetracycline and SXT. Several previous studies [4, 5, 19] have demonstrated similar variability in susceptibility profiles, while others [19] have indicated nearly complete susceptibility. As we move into the current era, the diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis is increasingly shifting towards PCR rather than culture-based detection [6]. Consequently, Aeromonas gastroenteritis is also expected to be diagnosed more frequently through PCR in the future. Regretfully, AST reports are less likely to be available for the clinician [20] and the selection of antimicrobial treatment might be guided mostly based on pre-existing data. The cumulative data from our study and previous study suggests that among the oral agents, fluoroquinolones are probably the most appropriate choice [1].

Our study was aimed to explore the molecular mechanism beyond AMR in Aeromonas gastroenteritis-related isolates. Here, our goal was only partially achieved as we were able to provide an explanation for the uncommon resistance phenotypes to SXT and tetracycline (sul1 and tetA/E, respectively) as previously described [21, 22]. The picture regarding the β-lactam antimicrobials was more complex. All isolates harbored a blaOXA type genes, all A. caviae harbored a blaMOX type genes, while non-caviae Aeromonas species harbored additional types of β-lactamase. These genetic profiles matched with the resistance to ampicillin, cefazolin and ampicillin-sulbactam, as reported by some but not all studies [23]. However, we could not find an explanation for the few cases of ampicillin or cefazolin susceptibility with the exception of one case with a S53Y substitution in the blaOXA−504 gene protein sequence which could have possibly altered the activity of this enzyme. The S53Y substitution in the blaOXA−504 gene protein has never been reported before, thus necessitating validation of its biochemical effect in-vitro. We also could not identify a correlation between the genomic features and the resistance to 2nd - or 3rd -generation cephalosporin phenotypes. This lack of correlation was also reported by a previous study [5] and is likely the result of de-repression of the class C β-lactamase expression [24]. Thus, genomic studies are probably limited in their ability to decipher β-lactamase resistance in Aeromonas species which requires also a gene expression analysis.

Using the standard MLST schema as reference, we found that the majority of isolates did not cluster into specific ST. This is similar to the results of Aeromonas species isolates from various clinical sites [5]. In a study of A. veronii isolated from patients with gastroenteritis the isolates were defined as “closely related” [25]; However, given the differences in WGS methodology and the absence of MLST as a reference, evaluating this description in comparison with our results is challenging. Furthermore, through the use of cgMLST, we were able to illustrate that apart from one pair of isolates, the differences between isolates, even within the same ST, were considerable. This finding suggests that direct or common-source transmission is unlikely.

In addition to the previously mentioned limitations concerning the correlations between AMR phenotypes and genotypes, our study’s ability to comprehensively represent the bacterial population of Aeromonas gastroenteritis-related isolates may have been constrained. This limitation stemmed from culturing being performed only following a positive PCR result, and it was not always successful (merely 68 out of 283 PCR-positive cases, 24%). Additional possible cause for the low rate of culture positivity might have been less than optimal choice of the selective/enrichment media. A low rate of culture positivity versus PCR (0.34 versus 2.9, 8.5%) was also noted in a before-after study of the same PCR kit [7]. Consequently, we were unable to include all cases within the defined period, potentially hindering the identification of putative transmission chains. Despite these limitations, our study offers additional insights into the prevalence and mechanisms of AMR, as well as novel data regarding the population structure of Aeromonas gastroenteritis-related isolates.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: The NGS datasets generated during the current study are available under BioProject accession number PRJNA1040111. In addition, all 58 A. caviae isolates were deposited in PubMLST under ID BIGSdb_20231207071129_2157505_94891.

References

Parker JL, Shaw JG. Aeromonas spp. clinical microbiology and disease. J Infect. 2011:109–18.

Von Graevenitz A. The role of Aeromonas in diarrhea: a review. Infection. 2007;35:59–64.

Grave I, Rudzate A, Nagle A, Miklasevics E, Gardovska D. Prevalence of Aeromonas Spp. Infection in Pediatric patients hospitalized with gastroenteritis in Latvia between 2020 and 2021. Children. 2022;9.

Senderovich Y, Ken-Dror S, Vainblat I, Blau D, Izhaki I, Halpern M. A molecular study on the prevalence and virulence potential of Aeromonas spp. recovered from patients suffering from diarrhea in Israel. PLoS ONE. 2012;7.

Sakurai A, Suzuki M, Ohkushi D, Harada S, Hosokawa N, Ishikawa K et al. Clinical features, genome epidemiology, and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Aeromonas Spp. Causing human infections: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10.

Sagas D, Adler A, Kasher C, Khamaysi K, Strauss M, Chazan B. The effect of the transition to molecular diagnosis on the epidemiology and the clinical characteristics of bacterial gastroenteritis in Northern Israel. Infect Dis. 2024;56:157–63. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2023.2282713

Zimmermann S, Horner S, Altwegg M, Dalpke AH. Workflow optimization for syndromic diarrhea diagnosis using the molecular Seegene Allplex™ GI-Bacteria(I) assay. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:1245–50.

Sachan N, Agarwal RK. Selective enrichment broth for the isolation of Aeromonas sp. from chicken meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;60:65–74.

Working group on fastidious organism. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk diffusion for infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria. M45, 3rd edition. Wayne, Philadelphia: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

CLSI. M100 performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI. 2021:18–260.

Alcock BP, Raphenya AR, Lau TTY, Tsang KK, Bouchard M, Edalatmand A et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019.

Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–20.

Ciufo S, Kannan S, Sharma S, Badretdin A, Clark K, Turner S, et al. Using average nucleotide identity to improve taxonomic assignments in prokaryotic genomes at the NCBI. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:2386–92.

Silva M, Machado MP, Silva DN, Rossi M, Moran-Gilad J, Santos S et al. chewBBACA: a complete suite for gene-by-gene schema creation and strain identification. Microb Genom. 2018;4.

Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421.

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–6.

Chen PL, Lamy B, Ko WC. Aeromonas dhakensis, an increasingly recognized human pathogen. Front Microbiol. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2016.

Chen PL, Tsai PJ, Chen CS, Lu YC, Chen HM, Lee NY, et al. Aeromonas stool isolates from individuals with or without diarrhea in southern Taiwan: predominance of Aeromonas veronii. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015;48:618–24.

States U, Iwamoto M, Huang JY, Cronquist AB, Medus C, Hurd S, et al. Bacterial enteric infections detected by culture-independent diagnostic tests. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:252–7.

Eid HM, El-Mahallawy HS, Shalaby AM, Elsheshtawy HM, Shetewy MM, Eidaroos NH. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila complex isolated from wild Mugil cephalus (striped mullet) and Mediterranean seawater. Vet World. 2022;15:55–64.

Fauzi NNFNM, Hamdan RH, Mohamed M, Ismail A, Zin AAM, Mohamad NFA. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility, and presence of drug resistance genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from freshwater fish in Kelantan and Terengganu states, Malaysia. Vet World. 2021;14:2064–72.

Chen P-L, Ko W-C, Wu C-J. Complexity of β-lactamases among clinical Aeromonas isolates and its clinical implications. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012 [cited 2013 Feb 6];45:398–403. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23031536

Walsh T. Distribution and expression of beta-lactamase genes among Aeromonas spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:171–8.

Liu F, Yuwono C, Tay ACY, Wehrhahn MC, Riordan SM, Zhang L. Analysis of global Aeromonas veronii genomes provides novel information on source of infection and virulence in human gastrointestinal diseases. BMC Genomics. 2022;23.

Acknowledgements

Nothing to declare.

Funding

Nothing to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS- data acquisition and interpretation; YH- data acquisition and interpretation, manuscript drafting; KL- data acquisition and interpretation; MS- data acquisition; MS- data acquisition and interpretation; BC-conception, study design and manuscript drafting; AA- conception and study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Emek Medical Center (0176-20-EMC).

Consent for participation and publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sagas, D., Hershko, Y., Levitskyi, K. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of antimicrobial resistance and population structure of gastroenteritis-related Aeromonas isolates. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 23, 45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00706-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00706-2