Abstract

Background

Asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression have each been linked to exposure to the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center (WTC) terrorist attacks (9/11). We described the prevalence and patterns of these conditions and associated health-related quality of life (HRQOL) fifteen years after the attacks.

Methods

We studied 36,897 participants in the WTC Health Registry, a cohort of exposed rescue/recovery workers and community members, who completed baseline (2003–2004) and follow-up (2015–16) questionnaires. Lower respiratory symptoms (LRS; cough, dyspnea, or wheeze), gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) and self-reported clinician-diagnosed asthma and GERD history were obtained from surveys. PTSD was defined as a score > 44 on the PTSD checklist, and depression as a score > 10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). Poor HRQOL was defined as reporting limited usual daily activities for > 14 days during the month preceding the survey.

Results

In 2015–16, 47.8% of participants had ≥1 of the conditions studied. Among participants without pre-existing asthma, 15.4% reported asthma diagnosed after 9/11; of these, 76.5% had LRS at follow up. Among those without pre-9/11 GERD, 22.3% reported being diagnosed with GERD after 9/11; 72.2% had GERS at follow-up. The prevalence of PTSD was 14.2%, and of depression was 15.3%. HRQOL declined as the number of comorbidities increased, and was particularly low among participants with mental health conditions. Over one quarter of participants with PTSD or depression reported unmet need for mental health care in the preceding year.

Conclusions

Nearly half of participants reported having developed at least one of the physical or mental health conditions studied by 2015–2016; comorbidity among conditions was common. Poor HRQOL and unmet need for health were frequently reported, particularly among those with post-9/11 PTSD or depression. Comprehensive physical and mental health care are essential for survivors of complex environmental disasters, and continued efforts to connect 9/11-exposed persons to needed resources are critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On September 11, 2001, terrorists launched two hijacked commercial jet planes into the World Trade Center (WTC) complex in Manhattan. In addition to immediately claiming over 2700 lives [1], the destruction of the WTC towers and nearby structures exposed hundreds of thousands of survivors to massive quantities of dust and fumes from collapsing buildings, the combustion of jet fuel, and lingering fires [2, 3], and to extreme psychological trauma [4]. Exposures to environmental hazards and psychological stressors continued during the months of rescue and recovery work that followed.

These experiences have had an enduring effect on the health of many 9/11 survivors. Respiratory symptoms were first described among heavily exposed firefighters [5], and subsequently documented among other rescue/recovery workers and lower Manhattan area community members [6,7,8,9,10]. Several other chronic aerodigestive disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), have since been linked to 9/11-related exposures [10,11,12]. Respiratory conditions and GERD have persisted for many of those affected, necessitating long-term follow-up and, often, chronic medication use.

The events of 9/11 have also taken a significant toll on the psychological health of many who were exposed [4, 6]. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which was found to be common among survivors during the first few years following 9/11, has persisted for many years for a substantial portion of survivors [13, 14]. Depression, often accompanying PTSD, is also common in this population [15, 16].

Considerable overlap across multiple 9/11-related conditions complicates the medical treatment and course of these conditions [17,18,19,20,21]. Having more than one of these conditions is associated with poorer outcomes [17, 18]. The combined effect of multiple, concurrent 9/11-related conditions was associated with low quality of life and productivity more than a decade after 9/11 [22, 23].

Updated information on the prevalence and patterns of the most common 9/11-related conditions and on the relationship between these conditions and quality of life is needed to inform the provision of health care for persons who were directly exposed to 9/11. We assessed the prevalence of asthma, GERD, PTSD and depression in 2015–16 among members of the World Trade Center Health Registry (Registry), a cohort of 9/11-exposed workers and lower Manhattan area community members, and estimated the impact on the total population of directly exposed persons.

Methods

Data source and study sample

We used data from the Registry, a voluntary cohort of rescue/recovery workers and volunteers, lower Manhattan area community members, and passersby on 9/11 who were directly exposed to the 9/11 terrorist attacks or subsequent rescue and recovery efforts [6, 24]. The Registry invited potential participants identified from lower Manhattan area building and employer lists (list-identified applicants) or through a broad-based, multi-lingual media campaign (self-identified applicants) to be screened for eligibility. Between September 5, 2003 and November 20, 2004, a total of 71,431 persons who met the eligibility criteria completed an enrollment questionnaire (Wave 1; 95% telephone administered, 5% face-to-face) regarding sociodemographic information, 9/11-related exposures and experiences, and health status and history. Enrollees are invited to provide updated health and quality of life information through periodic surveys, the most recent of which, Wave 4, was conducted in 2015–2016 [25] (questionnaire available at https://www1.nyc.gov/site/911health/researchers/health-data-tools.page). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene institutional review boards approved the Wave 1 and Wave 4 protocols.

The current study included enrollees who completed both the Wave 1 enrollment and Wave 4 questionnaires, were ≥ 18 years of age on 9/11/2001; and remained active participants in the Registry as of November 15, 2016.

9/11-related exposures

We used self-reported data from the Wave 1 questionnaire to define 9/11-related exposures. We considered several exposures that have been associated with 9/11-related health conditions in previous studies. Participants who reported being directly exposed to the massive cloud of dust and debris that resulted from the collapse of the World Trade Center towers and nearby infrastructure on 9/11 were considered to have dust cloud exposure. 9/11-related injury was defined as the report of incurring a cut, abrasion, or puncture wound; sprain or strain; burn; broken or dislocated bone; or concussion or head injury due to the 9/11 attacks. Personally witnessing a traumatic event was defined as having seen ≥1 of the following: an airplane strike a WTC tower; a building collapse; people running from the area or falling from the towers; or someone being injured or killed.

Enrollees who performed any rescue/recovery work, including volunteers, were considered rescue/recovery workers. Other enrollees were hierarchically categorized as lower Manhattan area residents, area workers (including staff or adult students from area schools), or passersby; for certain analyses, this group was considered collectively as community enrollees. For rescue/recovery workers, duration of work, date of first arrival for work, and whether a participant worked on the WTC dust and debris pile were considered. The latter two factors were operationalized as a single variable: arrived on 9/11 and worked on pile, arrived 9/11 but worked elsewhere, arrived 9/12–17, or arrived 9/18 or later.

Health and quality of life outcomes

Asthma was defined as clinician-diagnosed asthma reported on the Wave 1 or Wave 4 questionnaire, and GERD as clinician-diagnosed GERD reported on the Wave 4 questionnaire (GERD was not queried at Wave 1). Probable PTSD at Wave 4, subsequently referred to as PTSD for simplicity, was defined as a score of ≥44 on the 17-item PTSD Checklist (PCL-17), which inquired specifically about symptoms that were related to 9/11. Depression at Wave 4 was defined as a score ≥ 10 on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire. Lower respiratory symptoms (LRS) were defined as wheezing, dyspnea, or cough reported on > 8 of the 30 days preceding the interview, or use of physician-prescribed inhaler for breathing problems during the preceding 30 days. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) at Wave 4 were defined as heartburn or acid reflux reported at least weekly during the preceding year.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed using the number of days of poor physical or mental health reported during the 30 days preceding Wave 4, and the number of days on which poor health limited a respondent’s usual activities during the same period (each dichotomized at ≥14 days). General health, satisfaction with life, and health care access and utilization were also assessed at Wave 4. Participants were asked whether they had needed mental health care or counseling during the preceding year; if so, they were further asked whether they had received the care or counseling they needed. Those who reported needing care, but not having received it, were considered to have unmet need for mental health care. Similar questions were asked for physical health care, and unmet need was likewise considered reporting having needed, but not received, medical care during the preceding year.

Statistical analysis

We assessed whether Wave 4 participants differed from those who enrolled at Wave 1 but did not complete Wave 4 in terms of baseline socio-demographic characteristics, 9/11-related exposures, or self-reported health status using chi-square tests. We calculated the lifetime prevalence of asthma and GERD in the complete study sample; the prevalence of post-9/11-diagnosed asthma and GERD among participants without a history of the relevant condition before 9/11; and the prevalence of disease-related symptoms at Wave 4 among participants with post-9/11-diagnosed asthma and GERD. We computed the prevalence of PTSD and depression at Wave 4 among participants without a pre-9/11 diagnosis of the respective condition. We used population estimates from the 2010 US Census (www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf) to calculate the age-adjusted prevalence of asthma, GERD, PTSD, and depression at Wave 4. For participants who reported a year of diagnosis on the Wave 4 questionnaire, we calculated the annualized rate of post-9/11 asthma and GERD diagnoses between 2002 and 2015. We calculated the prevalence of indicators of HRQOL, general health and satisfaction, and health care access and utilization among participants with each health condition, and according to the number of health conditions diagnosed or present at the time of Wave 4.

To estimate the prevalence of asthma, GERD, PTSD, and depression among the approximately 409,000 persons who are thought to have been eligible for Registry enrollment [26], we applied the prevalence of post-9/11-diagnosed asthma and GERD and the prevalence of PTSD and depression at Wave 4 to the estimated number of people exposed. We calculated lower bound, mid value and upper bound estimates separately for rescue/recovery workers and community enrollees, using previously-described methods [24, 26]. The lower bound was calculated assuming that, among list-identified enrollees, those with symptoms potentially related to 9/11 exposure enrolled at a rate 50% higher than those who were asymptomatic. Estimates were rounded to the nearest integer.

Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). For all analyses, 2-sided P values were considered significant when less than 0.05.

Results

Of 67,504 Registry enrollees invited to complete the Wave 4 questionnaire, 36,864 (55%) participated (49% on paper, 51% via Web). Compared to non-participants, a higher proportion of participants were white; were aged 45 or older on 9/11; had completed college or higher education; had an annual family income of $75,000 or above; were co-habiting at Registry enrollment; were self-identified as potentially eligible for the Registry; or had performed rescue/recovery work after 9/11 (Appendix). The proportion exposed to the dust cloud on 9/11 was similar in participants and non-participants (52.1% vs. 51.2%, P = 0.02). The proportion of participants and non-participants who had personally witnessed trauma on 9/11 was also very similar (69.5% vs. 69.7%, P = 0.63). There was no statistical difference between the prevalence of asthma or GERD in the two groups at Registry enrollment; however, the proportion with PTSD at enrollment was lower in Wave 4 participants (15%) than in non-participants (18%, P < 0.01).

From the 36,864 Wave 4 participants, we excluded those who withdrew from the Registry (n = 21) after completing Wave 4, had their questionnaire completed by a proxy (n = 42), or were less than 18 years of age on 9/11 or missing age data (n = 904), resulting in a sample of 35,897 for subsequent analyses.

The lifetime prevalence of asthma was 25.4% (Table 1). Among participants without pre-9/11 asthma (n = 31,951), 15.4% were diagnosed with asthma after 9/11. The prevalence of post-9/11 asthma was higher among participants who were self-identified than among participants who were identified from building or employer lists (17.1% vs. 10.4%); among rescue/recovery participants (18.1%) than among other groups of enrollees; and among participants who were exposed to the 9/11 dust cloud than among those who were not (17.6% vs. 13.1%). Among rescue/recovery workers, the prevalence of asthma was higher among those with longer compared to shorter duration of work, and higher among those who had initiated rescue/recovery work on or soon after 9/11 than in those who began participating in rescue-recovery work later.

Among participants who were diagnosed with asthma after 9/11, most (76.5%) had persistent lower respiratory symptoms or were taking prescription medications for asthma at the time of Wave 4. The proportion with persistent symptoms was higher among participants with dust cloud exposure than among those without (78.1 vs. 74.0%). Among rescue/recovery workers with post-9/11 asthma, the prevalence of persistent lower respiratory symptoms at Wave 4 increased with longer duration of rescue/recovery work and earlier date of arrival for work.

The lifetime prevalence of GERD was 25.5%. Among participants without a pre-9/11 GERD diagnosis, 22.3% were diagnosed with the condition after 9/11; of these, 72.7% reported frequent GERS at the time of Wave 4. The prevalence of post-9/11 GERD was higher among participants who were self-identified than among those who were list-identified (24.3% vs. 16.7%), and among rescue/recovery workers (28.3%) than among other Registry enrollees. The prevalence was also higher among those with dust cloud exposure than among those without (24.3% vs. 20.3%), and, like asthma, was increasingly prevalent with longer duration of rescue/recovery work and earlier date of arrival for work.

The prevalence of PTSD and depression is shown in Table 2. Among participants without a pre-9/11 diagnosis of PTSD, the prevalence of PTSD at Wave 4 was 14.3%. The prevalence was higher among those who were self-identified than among those identified from building or employer lists (15.4% vs. 11.4%, respectively), and among rescue/recovery workers (15.3%) and passersby (15.7%) than among area residents (11.9%) or workers (13.7%). The prevalence was also higher among those who experienced each type of 9/11-related exposure examined than among those who had not experienced the respective exposure (e.g., 16.3% among those who personally witnessed traumatic events vs. 10.1% among those who did not). Among rescue/recovery workers, the prevalence increased with longer duration of work and earlier arrival at the scene.

Similar patterns were found for depression. The overall prevalence at Wave 4 was 15.3%, and was higher in those who were self-identified than among those who were not (15.8% vs. 13.8%); in rescue/recovery workers (16.3%) and passersby (18.2%) than among area residents (14.2%) or workers (13.9%); and among those who had been exposed to the 9/11 dust cloud or witnessed traumatizing events than among those who had not (17.5% vs. 12.9, and 16.4% vs. 12.6%, respectively). There was a suggestion of an increase in the prevalence of depression with increasing duration of rescue/recovery work, but no clear pattern in the prevalence of depression according to the date of arrival for work.

We examined patterns of overlap in the prevalence of the four 9/11-related conditions studied among 30,958 participants with complete data on the presence or absence of each condition. Nearly half of these participants (48.8%) had developed at least one of these conditions by Wave 4. The most common patterns were asthma alone (10.9% of participants with complete data); GERD alone (10.8%); asthma and GERD (5.8%); PTSD and depression (4.2%); depression alone (3.0%); all four conditions (2.5%); and PTSD alone (2.0%; data not shown in tables).

It is estimated that approximately 409,000 persons were eligible for Registry participation [26]. Projection of the Wave 4 questionnaire to the complete simulated population of directly exposed persons yielded estimates of approximately 39,938 cases of asthma; 61,678 of GERD; 46,762 of PTSD; and 52,440 of depression occurring since 9/11 (Table 3). We estimated that 162,070 persons who were directly exposed to the 9/11 WTC attacks (approximately 38,000 rescue/recovery workers and 124,000 community members) had developed one or more of these four conditions by 2015–16.

Participants with each of the four conditions studied reported considerably poorer HRQOL during the 30 days preceding completion of the Wave 4 questionnaire compared to participants with none of these conditions (Table 4). This was particularly pronounced among participants with a mental health condition; 46.6% of those with PTSD and 47.1% of those with depression reported that their health had limited their usual activities during 14 or more of the 30 days preceding Wave 4 completion. Similar patterns were found in measures of general health and satisfaction with life; 47.4% of participants with PTSD and 50.8% of those with depression reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with life, while 64.9% of those with PTSD and 66.0% of those with depression reported fair or poor general health. A high proportion of participants with PTSD reported unmet need for physical (7.4%) or mental health care (25.3%) during the past year. Similarly, among participants with depression, 7.1% reported unmet need for mental health care, and 26% reported unmet need for mental health care.

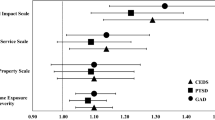

When HRQOL was examined according to the number of health conditions present at the time of Wave 4, the prevalence of each measure of poor HRQOL increased steadily with the number of conditions present (Fig. 1). There was a similar, though less pronounced, pattern when the prevalence of unmet need for health care was studied according to the number of conditions (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Although more than fifteen years have passed since the September 11, 2001 WTC terrorist attacks, their impact continues to unfold. Nearly half of enrollees in this large cohort of 9/11-exposed rescue/recovery workers and community members reported having developed one or more of the health conditions studied by 2015–16; extrapolation of these findings to the estimated complete population of directly-exposed survivors suggests that more than 162,000 persons are struggling with potentially 9/11-related mental or physical health symptoms today. Comorbidity among conditions was both common and closely tied to poor HRQOL in our study, implying that survivors of complex disasters are likely to require comprehensive, long-term medical follow-up and care. Participants with PTSD or depression reported the worst HRQOL and the highest levels of unmet need for mental health care, suggesting that increased efforts to reach this potentially vulnerable group are needed.

At 24.7%, the age-adjusted lifetime prevalence of asthma in our study was much higher than asthma prevalence estimates among adults reported in the 2015 National Health Interview Survey (12.7%) [27] and the 2014 New York City Community Health Survey (11.3%) [28], which measured self-reported clinician-diagnosed asthma using methods similar to the Registry’s. The age-adjusted point prevalence of PTSD in our sample, 13.1%, was also substantially higher than available population-based estimates, including the on-line 2011 National Stressful Events Survey (5.1% in past 6 months) [29] and the face-to-face 2001–2003 National Comorbidity Survey (6.1%) [30], although each of these measured PTSD differently than we did. Additionally, depression was more common in our sample (age-adjusted prevalence 14.5%) than in studies of the general population that used a similar version of the PHQ to define the condition (8.3%, 2013–14 New York City Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey [31]; 7.6%, 2009–2012 National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey [32]). We did not find population-based estimates for GERD that were measured comparably to ours. Our findings are broadly consistent with illness prevalence reports from other 9/11-exposed cohorts [10, 33, 34].

Each of the health conditions examined in this study was associated with poor HRQOL, but this association was particularly evident for the mental health conditions, with almost two thirds of participants with PTSD or depression reporting poor HRQOL during the month preceding completion of the questionnaire. HRQOL also declined steadily as the number of co-morbid conditions increased, consistent with previous studies [18, 22]. The close relationship between the mental health conditions studied and poor HRQOL may be due, largely, to the fact that PTSD and depression were usually present in combination with other comorbidities [22, 35]. Nonetheless, our results suggest that the toll associated with active PTSD and depression is substantial for society as well as for affected individuals, since both of these conditions were associated with frequent limitation of daily activities, and thus likely with a considerable decrease in productivity and other contributions.

Although health care for 9/11-related conditions is offered at no out-of-pocket cost to 9/11-exposed persons through the World Trade Center Health Program, many participants in this study reported unmet need for health care during the preceding year. The survey inquired about medical and mental health care in general, and did not specifically query whether the unmet need was for a condition that may be 9/11-related, so it is likely that some of the unmet needs reported were for other conditions. Nonetheless, the finding that 25% of patients with PTSD and 26% of those with depression reported a recent unmet need for mental health care is striking when compared to that of the general NYC population (13% [36]). These finding suggests that a more focused approach is needed to identify and address barriers that prevent enrollees with mental health symptoms from obtaining care. A previous study of such barriers in this cohort found that greater severity of mental health symptoms, a lack of health insurance, and lower levels of social support were associated with unmet need for mental health care [37]. Targeted outreach to individuals for whom these barriers are likely to exist, through programs such as the Registry’s Treatment Referral Program (which conducts personalized outreach to refer eligible enrollees to care through the WTC Health Program), is a crucial step toward improving access.

These results must be viewed in light of the fact that all data, including 9/11-related exposures and health outcomes, were self-reported, and that PTSD and depression were defined using screening instruments. Although we used tools such as the PCL-17 and PHQ that have been used extensively, including in multiple previous studies of 9/11-related health outcomes, estimates of the prevalence of conditions presented here are not a substitute for objectively collected clinical data. Instead, our results complement studies that include medically verified diagnoses by reflecting the ongoing needs of a larger and more diverse panel of 9/11 survivors than could be assessed otherwise. An additional consideration is that, while the Registry is the largest and most diverse cohort of 9/11-exposed persons in existence, it is a voluntary study that is estimated to have enrolled a minority of those exposed (17% [26]), and therefore may not be representative of the full spectrum of 9/11-exposed persons.

Approximately 55% of eligible Registry enrollees participated in the Wave 4 questionnaire, with enrollees who reported being white, highly educated, having a higher family income, or performing 9/11 rescue/recovery work more likely to participate in the Wave 4 suvey than their counterparts. Additionally, those who initially self-identified for screening for Registry eligibility were more likely to complete Wave 4 than were enrollees who were originally recruited through building or employer lists. Since symptoms and conditions were consistently more common among self-identified than list-identified enrollees in the current study, our results may tend to overestimate the prevalence of these conditions. On the other hand, because participants with PTSD at enrollment were less likely to remain active in the Registry than enrollees without PTSD, we may have underestimated the prevalence of PTSD among those affected. However, 9/11-related exposures were similar among Wave 4 participants and non-participants, suggesting that our findings on the relationships between such exposures and health end-points do not suffer from systematic bias due to differential attrition of this nature.

The current study addresses only the most common conditions that are associated with 9/11 exposure; we did not include other 9/11-related conditions, such as sarcoidosis, that are less common, yet potentially severe or even fatal, or various types of cancer which are being investigated as potentially associated with 9/11 exposure. Our description of comorbidities does not represent the complexity of the interrelationships among these conditions, an area of study which will be developed further in subsequent analyses. The full spectrum of the down-stream impacts of 9/11-related conditions, such as early retirement [23] or other measures of lost productivity, is also not examined here.

The persistently high prevalence of asthma, GERD, PTSD and depression 15 years after 9/11 and the association of these conditions with poor HRQOL provide strong support for the continuation of both medical care and health monitoring for 9/11-exposed persons. The poorer HRQOL outcomes and high levels of unmet mental health care need among those with mental health conditions in this population, despite the availability of care for 9/11-related mental health conditions through the WTC Health Program, are concerning. Outreach to inform exposed persons of available health resources, focusing on sub-groups with a particularly high prevalence of mental health conditions, is essential. Long-term monitoring of this cohort can inform preparation for and response to other complex disasters.

Abbreviations

- 9/11:

-

September 11, 2001 World Trade Center terrorist attacks

- GERD:

-

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GERS:

-

gastroesophageal reflux symptoms

- HRQOL:

-

health-related quality of life

- PTSD:

-

posttraumatic stress disorder

- WTC:

-

World Trade Center

References

CDC. Deaths in World Trade Center terrorist attacks—New York City, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Sep 11;51:1–5.

Landrigan PJ, Lioy PJ, Thurston G, Berkowitz G, Chen LC, Chillrud SN, et al. NIEHS World Trade Center Working Group. Health and environmental consequences of the World Trade Center disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:731–9.

Claudio L. Environmental aftermath. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:528–36.

Stellman JM, Smith RP, Katz CL, Sharma V, Charney DS, Herbert R, et al. Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in world trade center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: the psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1248–53.

Prezant DJ, Weiden M, Banauch GI, McGuinness G, Rom WN, Aldrich TK, Kelly KJ. Cough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center site. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:806–15.

Brackbill RM, Hadler JL, DiGrande L, Ekenga CC, Farfel MR, Friedman S, et al. Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center terrorist attack. JAMA. 2009;302:502–16.

Lin S, Jones R, Reibman J, Morse D, Hwang SA. Lower respiratory symptoms among residents living near the World Trade Center, two and four years after 9/11. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2010;16:44–52.

Reibman J, Lin S, Hwang SA, Gulati M, Bowers JA, Rogers L, et al. The World Trade Center residents’ respiratory health study: new-onset respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:406–11.

Wheeler K, McKelvey W, Thorpe L, Perrin M, Cone J, Kass D, et al. Asthma diagnosed after 11 September 2001 among rescue and recovery workers: findings from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1584–90.

Wisnivesky JP, Teitelbaum SL, Todd AC, Boffetta P, Crane M, Crowley L, et al. Persistence of multiple illnesses in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers: a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:888–97.

de la Hoz RE, Christie J, Teamer JA, Bienenfeld LA, Afilaka AA, Crane M, et al. Reflux symptoms and disorders and pulmonary disease in former World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers and volunteers. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:1351–4.

Li J, Brackbill RM, Stellman SD, Farfel MR, Miller-Archie SA, Friedman S, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and comorbid asthma and posttraumatic stress disorder following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on World Trade Center in New York City. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1933–41.

Maslow CB, Caramanica K, Welch AE, Stellman SD, Brackbill RM, Farfel MR. Trajectories of scores on a screening instrument for PTSD among World Trade Center rescue, recovery, and clean-up workers. J Trauma Stress. 2015 Jun;28:198–205.

Welch AE, Caramanica K, Maslow CB, Brackbill RM, Stellman SD, Farfel MR. Trajectories of PTSD among lower Manhattan residents and area workers following the 2001 World Trade Center disaster, 2003-2012. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Apr;29:158–66.

Caramanica K, Brackbill RM, Liao T, Stellman SD. Comorbidity of 9/11-related PTSD and depression in the World Trade Center Health Registry 10-11 years postdisaster. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27:680–8.

Bowler RM, Kornblith ES, Li J, Adams SW, Gocheva VV, Schwarzer R, Cone JE. Police officers who responded to 9/11: comorbidity of PTSD, depression, and anxiety 10-11 years later. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59:425–36.

Nair HP, Ekenga CC, Cone JE, Brackbill RM, Farfel MR, Stellman SD. Co-occurring lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5 to 6 years after the World Trade Center terrorist attack. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1964–73.

Friedman SM, Farfel MR, Maslow C, Jordan HT, Li J, Alper H, et al. Comorbid persistent lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5–6 years post-9/11 in responders enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:1251–61.

Luft BJ, Schechter C, Kotov R, Broihier J, Reissman D, Guerrera K, et al. Exposure, probable PTSD and lower respiratory illness among World Trade Center rescue, recovery and clean-up workers. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1069–79.

Kotov R, Bromet EJ, Schechter C, Broihier J, Feder A, Friedman-Jimenez G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the risk of respiratory problems in World Trade Center responders: longitudinal test of a pathway. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:438–48.

Niles JK, Webber MP, Gustave J, Cohen HW, Zeig-Owens R, Kelly KJ, et al. Comorbid trends in World Trade Center cough syndrome and probable posttraumatic stress disorder in firefighters. Chest. 2011;140:1146–54.

Li J, Zweig KC, Brackbill RM, Farfel MR, Cone JE. Comorbidity amplifies the effects of post-9/11 posttraumatic stress disorder trajectories on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:651–60.

Yu S, Brackbill RM, Locke S, Stellman SD, Gargano LM. Impact of 9/11-related chronic conditions and PTSD comorbidity on early retirement and job loss among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59:731–41.

Farfel M, DiGrande L, Brackbill R, Prann A, Cone J, Friedman S, et al. An overview of 9/11 experiences and respiratory and mental health conditions among World Trade Center Health Registry enrollees. J Urban Health. 2008;85:880–909.

Yu S, Alper HE, Nguyen AM, Brackbill RM, Turner L, Walker DJ, et al. The effectiveness of a monetary incentive offer on survey response rates and response completeness in a longitudinal study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:77.

Murphy J, Brackbill RM, Thalji L, Dolan M, Pulliam P, Walker DJ. Measuring and maximizing coverage in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Stat Med. 2007;26:1688–701.

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Technical notes for summary health statistics tables: National Health Interview Survey. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/SHS/tables.htm. Accessed 3 July 2018.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Survey 2014: public use dataset accessed 2 Oct 2017.

Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:537–47.

Rao AS, Scher AI, Vieira RVA, Merikangas KR, Metti AL, Peterlin BL. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on the burden of migrane: results from the National Comorbidity Survey-replication. Headache. 2015;55:1323–41.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New York City Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-14: public use dataset accessed 2 Oct 2017.

Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009-2012. NCHS data brief, no 172. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2014.

Bromet EJ, Hobbs MJ, Clouston SA, Gonzalez A, Kotov R, Luft BJ. DSM-IV post-traumatic stress disorder among World Trade Center responders 11–13 years after the disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11). Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:771–83.

Yip J, Zeig-Owens R, Webber MP, Kablanian A, Hall CB, Vossbrinck M, et al. World Trade Center-related physical and mental health burden among New York City Fire Department emergency medical service workers. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:13–20.

McLeay SC, Harvey WM, Romaniuk MN, Crawford DH, Colquhoun DM, Young RM, et al. Physical comorbidities of post-traumatic stress disorder in Australian Vietnam War veterans. Med J Aust. 2017;206:251–7.

Tuskeviciute R, Hoenig J, Norman C. Depression among New York City Adults. NYC Vital Signs. 2018;17:1–4.

Ghuman SJ, Brackbill RM, Stellman SD, Farfel MR, Cone JE. Unmet mental health care need 10-11 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks: 2011-2012 results from the World Trade Center Health Registry. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:491.

Acknowledgements

Previously presented as an abstract: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists June 2017, Boise, Idaho.

Funding

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Numbers 2 U50/OH009739 and 5 U50/OH009739 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); U50/ATU272750 from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), CDC, which included support from the National Center for Environmental Health, CDC; and by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH, CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Availability of data and materials

de-identified data from all Registry surveys are available at https://www1.nyc.gov/site/911health/researchers/health-data-tools.page

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ conceived of the manuscript and the analytic approach and wrote the manuscript, with input from SO, JL, CS, RB, JC, and MF. SO conducted the statistical analyses. CG provided editorial and subject matter expertise. HM assisted with visual presentation of the data. JL assisted with finalization of the manuscript and references.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene institutional review boards approved the Wave 1 and Wave 4 protocols. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each Registry participant at enrollment.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jordan, H.T., Osahan, S., Li, J. et al. Persistent mental and physical health impact of exposure to the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Environ Health 18, 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0449-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0449-7