Abstract

Background

Health facilities’ availability of malaria diagnostic tests and anti-malarial drugs (AMDs), and the correctness of treatment are critical for the appropriate case management, and malaria surveillance programs. It is also reliable evidence for malaria elimination certification in low-transmission settings. This meta-analysis aimed to estimate summary proportions for the availability of malaria diagnostic tests, AMDs, and the correctness of treatment.

Methods

The Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, Embase, and Malaria Journal were systematically searched up to 30th January 2023. The study searched any records reporting the availability of diagnostic tests and AMDs and the correctness of malaria treatment. Eligibility and risk of bias assessment of studies were conducted independently in a blinded way by two reviewers. For the pooling of studies, meta-analysis using random effects model were carried out to estimate summary proportions of the availability of diagnostic tests, AMDs, and correctness of malaria treatment.

Results

A total of 18 studies, incorporating 7,429 health facilities, 9,745 health workers, 41,856 febrile patients, and 15,398 malaria patients, and no study in low malaria transmission areas, were identified. The pooled proportion of the availability of malaria diagnostic tests, and the first-line AMDs in health facilities was 76% (95% CI 67–84); and 83% (95% CI 79–87), respectively. A pooled meta-analysis using random effects indicates the overall proportion of the correctness of malaria treatment 62% (95% CI 54–69). The appropriate malaria treatment was improved over time from 2009 to 2023. In the sub-group analysis, the correctness of treatment proportion was 53% (95% CI 50–63) for non-physicians health workers and 69% (95% CI 55–84) for physicians.

Conclusion

Findings of this review indicated that the correctness of malaria treatment and the availability of AMDs and diagnostic tests need improving to progress the malaria elimination stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide malaria case incidence has decreased by 27% from 2000 to 2015, and from 2015 to 2019 it reduced by less than 2%. Since 2015, it shows a slowing rate of decrease [1]. Recent noteworthy developments have been performed towards malaria elimination worldwide. However, malaria remains a major public health concern in several tropical areas, particularly in countries with a weak health system [2, 3].

The World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted the appropriate and prompt treatment of malaria cases with first-line anti-malarial drugs (AMDs) in the first 24 h after diagnosis, and malaria guidelines include the indicator “percentage of patients with suspected malaria who received a parasitological test” [4]. It needs the availability of malaria diagnostic tests and AMDs in health facilities to prevent fatal outcomes and prevention of re-establishment of malaria in low transmission areas [5]. However, malaria case management remains a significant shortcoming in various settings [6, 7].

Meta-analysis and empirical studies indicated that decreasing healthcare systems readiness and health service providers’ practice in the appropriate malaria case management, unavailability of Rapid diagnostic test (RDT), AMDs, and shortage in early case detection with appropriate malaria diagnostic tests are major concerns to obtain malaria elimination certification and prevention of re-introduction, especially in countries where malaria transmission is low or interrupted [1, 7, 8].

Furthermore, it seems that COVID-19 pandemic imposed great challenges for malaria elimination and surveillance programmes due to the disruption in early case detection and appropriate case management of febrile and suspected malaria cases both in high and low transmission areas and potential re-introduction regions [9,10,11].

Therefore, evaluating health facilities’ availability for AMDs and diagnostic tests and healthcare providers’ practice in the appropriate malaria treatment is critical for early case detection, malaria surveillance systems, and elimination programmes [12, 13]. This meta-analysis aimed to estimate summary proportions for the availability of malaria diagnostic tests and AMDs, and the correctness of malaria treatment.

Methods

Search strategy

The Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, Embase, and Malaria Journal were systematically searched up to 30th January 2023. Grey literature was searched from Open grey, WHO and CDC reports, congress papers, and records. The study searched any records reporting the availability of diagnostic tests and AMDs, and the correctness of treatment of malaria using text words, synonyms, and medical subject headings (MeSH terms).

The initial search included malaria and/or fever or febrile. Then the study search used the relevant MeSH terms and text words related to malaria and febrile diseases in conjunction with(((((((((((((((malaria{Title/Abstract}) OR (fever{Title/Abstract})) OR (febrile{Title/Abstract})) AND (treatment{Title/Abstract})) ) OR (case management)) OR (test)) OR (diagnosis)) OR (rapid diagnostic)) OR (antimalarial)) OR (anti-malarial)) AND (health worker)) OR (healthcare)) OR (provider)) OR (performance)) OR (practice) AND ((exclude preprints{Filter} AND (humans{Filter}) AND (English{Filter})). The study used a relevant search strategy based on each database search option. The reference lists of the retrieved studies, related reviews and international reports, such as WHO were also searched.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were any cross-sectional or descriptive records/articles reporting the availability of malaria diagnostic tests (RDT test and/or microscopic) and/or AMDs in the health facilities for malaria cases and/or febrile patients, and also assessed health workers’ correctness of treatment at all age groups. The correctness of malaria treatment was defined as prescribing the appropriate and recommended dosage of the first-line AMDs for malaria parasite-positive cases; not only prescribing any anti-malarial drugs; particularly artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) [14]. Exclusion criteria were editorials, letters, reviews, conference abstracts, and commentaries. We also excluded Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) and qualitative studies, and studies carried out for active case finding and/or screening and assessed the effects of any specific intervention on malaria case management.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the availability of malaria diagnostic tests (RDT test and/or microscopic) and AMDs; and the second outcome was health workers’ correctness of treatment with the first-line AMDs for malaria parasite-positive cases.

Data selection and extraction

Two reviewers (HA, EDE) assessed the eligibility of records independently in a blinded method. The title and abstract were screened at first, and the two reviewers screened and selected relevant full-text articles. Data were extracted based on the pre-specified criteria into an Excel sheet and then transferred to statistical analysis software. The extracted data was the year, authors, country, study design, sample size, number of health facilities in each study, malaria patients, febrile patients, and health worker type and number.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

The quality and the risk of bias were evaluated using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [15]. This instrument considered the following parameters including adequate sample size, sampling method and plan (using unbiased and random sampling methods), using appropriate data collection methods, sample representativeness, inclusion/exclusion criteria, adequacy of response rate, and correct and appropriate statistical analysis.

The final scoring system included 11 criteria for rating different risk of bias elements for each eligible article out of 12 scores. Scale weights (unbiased sampling and data collection method had the highest weights) were recommended by authors for each parameter of the scoring system, as proposed in other meta-analyses. Table 1 categorized the studies into three levels of risk of bias including low risk (9–12 points), moderate risk (5–8 points), and high risk (< 5 points) of risk of bias evolution.

Statistical analysis

STATA version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was carried out for data analysis. The summary proportions with a 95% Confidence interval (CI) were calculated for the availability of malaria diagnostic tests, anti-malarial drugs, and the correctness of malaria treatment. Pooled proportions of the availability of malaria diagnostic tests, AMDs, and the correctness of treatment were calculated using the Der Simonian and Laird method via the random effects model15. Cochran’s Q test and I2 were performed for heterogeneity between studies assessing. Sub-group meta-analysis by health worker type was used for the summary proportion of the correctness of malaria treatment. Trend of the correctness of malaria treatment was estimated by considering standard error in each study over the years [1, 16].

Results

Study selection and characteristics

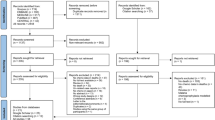

A total of 21,284 records were retrieved in the review. Of those 10, 372 records were removed due to duplication. Of which, 12,582 were excluded due to irrelevant titles, abstracts, and texts. In this step, 74 articles were considered for the full-text review. Of which, 53 articles were removed due to not original research, ineligible information, and ineligible outcome. Of which, 3 original studies were excluded due to the high risk of bias assessment. Finally, 18 articles were involved in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Of 18 articles, the correctness of malaria treatment was reported in 16 articles, the availability of anti-malarial drugs in 12 studies, and the availability of malaria diagnostic tests (RDT or/or microscopic) in 10 studies.

Table 1 shows that the characteristics of the studies included. All studies included were cross-sectional designs and published between 2009 and 2023 and the majority of studies had been conducted in Africa. It is notable that there were no eligible studies found from low transmission areas or countries in the elimination phase. Although some of the studies included were not reported absolute numbers of the study characteristics, however, a total of 7,429 health facilities (HFs), 9,745 health workers, 41, 856 febrile patients, and 15,398 confirmed malaria patients have participated in the study (Table 1).

Meta-analysis

For the pooling of studies, a meta-analysis using random effects model for 10 studies indicated the summary proportion of the availability of malaria diagnostic tests (RDTs and/or microscopic) in health facilities, 76% (95% CI 67–84%); I2 = 83.6% (Fig. 2). Likewise, the pooled proportion of the availability of the first-line AMDs in health facilities using random effects for 12 studies was 83% (95% CI 79–87%); I2 = 51% (Fig. 3).

Figure 4 shows the meta-analysis proportion of the correctness of malaria treatment with the first-line AMDs. The correctness of malaria treatment varied from 43% in Abiodun et al. [17] and Plucinski et al. [18] studies to 92% in Namuyinga et al. [19] study. A pooled meta-analysis of 16 studies using random effects indicates overall summary correctness of malaria treatment proportion 62% (95% CI 54–69%); I2 = 97%.

Overall, the appropriate malaria treatment was improved over time from 2009 to 2023 (Fig. 5). Concerning subgroup meta-analysis proportion of correctness of malaria treatment by health worker type, the pooled meta-analysis using random effects was 53% (95% CI 50–63%; 10 studies) for non-physicians healthcare providers and 69% (95% CI 55–84%; 6 studies) for physicians (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Given that malaria testing, the appropriate treatment of confirmed malaria cases with the first-line AMDs, and the availability of malaria diagnostic tests for early case detection are the major components of appropriate malaria case management [8, 14]; this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed to estimate the pooled proportion of appropriate malaria treatment, availability of AMDs and malaria diagnostic tests in health facilities. The current study findings revealed that no study was conducted in low malaria transmission areas and countries in the elimination phase and all studies included have been conducted in malaria transmission settings.

However, evidence indicated that in low-transmission countries the health system vigilance and health workers’ readiness including awareness and practice in the correct management of suspected malaria was decreased due to the long absence of malaria cases [1]. The prevention of the re-introduction of malaria and malaria elimination programmes are susceptible to serious challenges [7]. Previous findings indicated that to achieve malaria elimination criteria, the malaria surveillance system should be able to detect, manage and report any new malaria cases to the health system; and the malaria surveillance system should be included effective vigilance, which in combination with other components could prevent the re-introduction of malaria transmission [8].

This review found the overall proportion of the correctness of malaria treatment, the availability of AMDs, and malaria diagnostic tests was 62%, 83%, and 76%, respectively. In accordance with the current study, the appropriate malaria treatment was 60% in a study by Azizi et al. [1]. 59% in a study by Cohen et al. [20], and 56% in a study by Zurovac et al. [21]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, health workers’ compliance with RDT results was 83%, and work experience, patient expectations, health worker type, and perceived effectiveness of the test were related factors [22]. In a meta-analysis study, Kattenberg et al. recommended that RDTs and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) had good performance characteristics to serve as alternatives for the diagnosis of malaria in pregnancy [23]. In a systematic review conducted by Visser et al., the RDT uptake varied widely from 8 to 100%, and the provision of ACT for patients testing positive varied from 30 to 99% [24]. A review study in sub-Saharan Africa found malaria RDTs are generally used well, though compliance with test results is variable [25].

Therefore, this review suggests evaluating health system vigilance and healthcare providers’ readiness in the correct management of suspected malaria in low transmission settings in addition to high transmission settings, and it is a significant component to obtaining malaria elimination certification criteria.

The correctness of malaria treatment with the first-line AMDs in the particular ACT is a major component of the appropriate malaria case management for malaria surveillance systems [26]. Treatment of malaria patients with first-line AMDs and ACT is very important to prevent the development of severe and fatal outcomes [27]. Evidence showed that the case fatality rate of untreated severe malaria has been estimated 13–21% [28]. The WHO places special emphasis on treating all malaria cases with first-line AMDs in the first 24 h after diagnosis [13]. Therefore, the correctness and appropriate malaria treatment depend on the availability of AMDs and diagnostic tests in health facilities and also it needs healthcare providers’ practice in case management and health systems vigilance [29, 30]. Although, early case detection and malaria cases treatment with ACT have been suggested by the WHO in 2006 [31], stocking and availability of ACT and malaria diagnostic tests were incomplete in some included studies.

In the poor availability of RDT, the introduction of the quality assurance system for malaria microscopy, prioritization of microscopy for febrile inpatient management, and increased health facilities availability of malaria RDTs focusing on outpatient malaria screening should be the programmatic and organizational priorities targeting improved diagnostic services in the various settings [17].

This review provided reliable evidence for appraising health system vigilance and healthcare provider practice as also the weakness and strengths of malaria surveillance programmes. Malaria testing and early case detection from suspected febrile cases can increase timely treatment and prevent lethal outcomes, especially in high transmission settings [2, 32]. In low malaria transmission settings, it could timely early case detection of imported cases and provide reliable evidence to measure the prevention of re-establishment of malaria transmission and also WHO elimination criteria [7, 8].

Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate the pooled proportion estimate of the availability of malaria diagnostic tests and AMDs in health facilities, and the correctness of malaria treatment by health workers. However, the present study had limitations. The main concern was between-studies heterogeneity due to including studies (with cross-sectional design) from different countries with different malaria surveillance systems and transmission levels may lead to information and reporting bias for estimating the pooled prevalence estimates. However, no study was found from countries with low transmission and/or clear areas in the elimination phase, and all the studies included were conducted in low malaria transmission settings (homogeneous). Moreover, the study used/involved health worker type, and the appropriateness of the study methods, sampling, and conducting (risk of bias) in the sub-group meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Findings of this review indicated that the correctness of malaria treatment and the availability of anti-malarial drugs and diagnostic tests need improving to progress the malaria elimination stage.

Recommendations

Establishments of an effective supply chain for malaria diagnostic tests and AMDs, quality-assured diagnostics, ongoing support for healthcare providers to deliver care conferring to the guidelines, and close monitoring of health systems readiness and practices will ultimately determine the attainment of the policy translation continue the importance of practice and quality of appropriate malaria case-management are required.

In low transmission areas and countries in the elimination phase, investigations and in-service training programs are needed to evaluate health systems and healthcare providers’ readiness and practice in the appropriate case management of suspected malaria and prevention of malaria re-establishment.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- AMDs:

-

Anti-malarial drugs

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CHWs:

-

Community health workers

- HFs:

-

Health facilities

- HWs:

-

Health workers

- RDTs:

-

Rapid diagnostic tests

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Azizi H, Majdzadeh R, Ahmadi A, Esmaeili ED, Naghili B, Mansournia MA. Health workers readiness and practice in malaria case detection and appropriate treatment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Malar J. 2021;20:420.

Landier J, Parker DM, Thu AM, Carrara VI, Lwin KM, Bonnington CA, et al. The role of early detection and treatment in malaria elimination. Malar J. 2016;15:363.

White N, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien T, Faiz M, Mokuolu O, Dondorp A. Malaria. Lancet. 2014;383:723–35.

WHO. A framework for malaria elimination. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Rao VB, Schellenberg D, Ghani AC. The potential impact of improving appropriate treatment for fever on malaria and non-malarial febrile illness management in under-5s: a decision-tree modelling approach. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69654.

Nkumama IN, O’Meara WP, Osier FH. Changes in malaria epidemiology in Africa and new challenges for elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:128–40.

Azizi H, Davtalab-Esmaeili E, Farahbakhsh M, Zeinolabedini M, Mirzaei Y, Mirzapour M. Malaria situation in a clear area of Iran: an approach for the better understanding of the health service providers’ readiness and challenges for malaria elimination in clear areas. Malar J. 2020;9:114.

Azizi H, Majdzadeh R, Ahmadi A, Raeisi A, Nazemipour M, Mansournia MA, et al. Development and validation of an online tool for assessment of health care providers’ management of suspected malaria in an area, where transmission has been interrupted. Malar J. 2022;21:304.

Azizi H, Esmaeili ED. Is COVID-19 posed great challenges for malaria control and elimination? Iran J Parasitol. 2021;16:346–7.

Hogan AB, Jewell BL, Sherrard-Smith E, Vesga JF, Watson OJ, Whittaker C, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1132–41.

Rogerson SJ, Beeson JG, Laman M, Poespoprodjo JR, William T, Simpson JA, et al. Identifying and combating the impacts of COVID-19 on malaria. BMC Med. 2020;18:239.

Chipukuma HM, Zulu JM, Jacobs C, Chongwe G, Chola M, Halwiindi H, et al. Towards a framework for analyzing determinants of performance of community health workers in malaria prevention and control: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:22.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Reyburn H. New WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. BMJ. 2020;340:c2637.

Esmaeili ED, Azizi H, Sarbazi E, Khodamoradi F. The global case fatality rate due to COVID-19 in hospitalized elderly patients by sex, year, gross domestic product, and continent: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. New Microbes new Infect. 2023;51:101079.

Esmaeili ED, Fakhari A, Naghili B, Khodamoradi F, Azizi H. Case fatality and mortality rates, socio-demographic profile, and clinical features of COVID‐19 in the elderly population: a population‐based registry study in Iran. J Med Virol. 2022;94:2126–32.

Ojo AA, Maxwell K, Oresanya O, Adaji J, Hamade P, Tibenderana JK, et al. Health systems readiness and quality of inpatient malaria case-management in Kano State, Nigeria. Malar J. 2020;19:384.

Plucinski MM, Ferreira M, Ferreira CM, Burns J, Gaparayi P, João L, et al. Evaluating malaria case management at public health facilities in two provinces in Angola. Malar J. 2017;16:186.

Namuyinga RJ, Mwandama D, Moyo D, Gumbo A, Troell P, Kobayashi M, et al. Health worker adherence to malaria treatment guidelines at outpatient health facilities in southern Malawi following implementation of universal access to diagnostic testing. Malar J. 2017;16:40.

Cohen JL, Leslie HH, Saran I, Fink G. Quality of clinical management of children diagnosed with malaria: a cross-sectional assessment in 9 sub-saharan african countries between 2007–2018. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003254.

Zurovac D, Machini B, Kiptui R, Memusi D, Amboko B, Kigen S, et al. Monitoring health systems readiness and inpatient malaria case-management at kenyan county hospitals. Malar J. 2018;17:213.

Kabaghe AN, Visser BJ, Spijker R, Phiri KS, Grobusch MP, Van Vugt M. Health workers’ compliance to rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) to guide malaria treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J. 2016;15:163.

Kattenberg JH, Ochodo EA, Boer KR, Schallig HD, Mens PF, Leeflang MM. Systematic review and meta-analysis: rapid diagnostic tests versus placental histology, microscopy and PCR for malaria in pregnant women. Malar J. 2011;10:321.

Visser T, Bruxvoort K, Maloney K, Leslie T, Barat LM, Allan R, et al. Introducing malaria rapid diagnostic tests in private medicine retail outlets: a systematic literature review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0173093.

Boyce MR, O’Meara WP. Use of malaria RDTs in various health contexts across sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:470.

WHO. Compendium of WHO malaria guidance: prevention, diagnosis, treatment, surveillance and elimination. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Whitty CJ, Chandler C, Ansah E, Leslie T, Staedke SG. Deployment of ACT antimalarials for treatment of malaria: challenges and opportunities. Malar J. 2008;7(Suppl 1):7.

Sinclair D, Zani B, Donegan S, Olliaro P, Garner P. Artemisinin-based combination therapy for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD007483.

WHO. Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance: results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 6 (2014–2015). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Mubi M, Janson A, Warsame M, Mårtensson A, Källander K, Petzold MG, et al. Malaria rapid testing by community health workers is effective and safe for targeting malaria treatment: randomised cross-over trial in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19753.

Thwing J, Eisele TP, Steketee RW. Protective efficacy of malaria case management for preventing malaria mortality in children: a systematic review for the lives Saved Tool. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):14.

Schapira A, Kondrashin A. Prevention of re-establishment of malaria. Malar J. 2021;20:243.

Signorell A, Awor P, Okitawutshu J, Tshefu A, Omoluabi E, Hetzel MW, et al. Health worker compliance with severe malaria treatment guidelines in the context of implementing pre-referral rectal artesunate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and Uganda: an operational study. PLoS Med. 2023;20:e1004189.

Mohamoud AM, Yousif MEA, Saeed OK. Factors affecting adherence to National malaria treatment guidelines in the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of malaria in pregnancy among healthcare workers in public health facilities in Jowhar District, Somalia. Health. 2022;14:1114–29.

Otambo WO, Olumeh JO, Ochwedo KO, Magomere EO, Debrah I, Ouma C, et al. Health care provider practices in diagnosis and treatment of malaria in rural communities in Kisumu County, Kenya. Malar J. 2022;21:129.

Kibira D, Ssebagereka A, van den Ham HA, Opigo J, Katamba H, Seru M, et al. Trends in access to anti-malarial treatment in the formal private sector in Uganda: an assessment of availability and affordability of first‐line anti‐malarials and diagnostics between 2007 and 2018. Malar J. 2021;20:142.

Garg S, Gurung P, Dewangan M, Nanda P. Coverage of community case management for malaria through CHWs: a quantitative assessment using primary household surveys of high-burden areas in Chhattisgarh state of India. Malar J. 2020;19:213.

Aguemon B, Damien BG, Hinson AV, Padonou G, Agbessinou AFB, Ouendo EM, et al. Malaria case-management in urban area: various challenges in public and private health facilities in Benin, West Africa. Open Public Health J. 2018;11:54–61.

Gallay J, Mosha D, Lutahakana E, Mazuguni F, Zuakulu M, Decosterd LA, et al. Appropriateness of malaria diagnosis and treatment for fever episodes according to patient history and anti-malarial blood measurement: a cross-sectional survey from Tanzania. Malar J. 2018;7:209.

Pulford J, Smith I, Mueller I, Siba PM, Hetzel MW. Health worker compliance with a ‘test and treat’malaria case management protocol in Papua New Guinea. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0158780.

Bamiselu OF, Ajayi I, Fawole O, Dairo D, Ajumobi O, Oladimeji A, et al. Adherence to malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines among healthcare workers in Ogun State, Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:828.

Zurovac D, Guintran J-O, Donald W, Naket E, Malinga J, Taleo G. Health systems readiness and management of febrile outpatients under low malaria transmission in Vanuatu. Malar J. 2015;14:489.

Landman KZ, Jean SE, Existe A, Akom EE, Chang MA, Lemoine JF, et al. Evaluation of case management of uncomplicated malaria in Haiti: a national health facility survey, 2012. Malar J. 2015;14:394.

Steinhardt LC, Chinkhumba J, Wolkon A, Luka M, Luhanga M, Sande J, et al. Quality of malaria case management in Malawi: results from a nationally representative health facility survey. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89050.

Rowe AK, de León GFP, Mihigo J, Santelli ACF, Miller NP, Van-Dúnem P. Quality of malaria case management at outpatient health facilities in Angola. Malar J. 2009;8:275.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Research Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

The present study was financially supported, reviewed and supervised by Research Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine to number 63609, at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This review study has been designed by HA. All authors conceived, searched, extracted the relevant records, and synthesized the data that led to the manuscript or played an important role in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data or both. All authors contributed in the manuscript development and/or made substantive suggestions for revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences to number: IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1399.049. No primary data were collected for this review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Azizi, H., Davtalab Esmaeili, E. & Abbasi, F. Availability of malaria diagnostic tests, anti-malarial drugs, and the correctness of treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J 22, 127 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04555-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04555-w