Abstract

The global malaria burden sometimes obscures that the genus Plasmodium comprises diverse clades with lineages that independently gave origin to the extant human parasites. Indeed, the differences between the human malaria parasites were highlighted in the classical taxonomy by dividing them into two subgenera, the subgenus Plasmodium, which included all the human parasites but Plasmodium falciparum that was placed in its separate subgenus, Laverania. Here, the evolution of Plasmodium in primates will be discussed in terms of their species diversity and some of their distinct phenotypes, putative molecular adaptations, and host–parasite biocenosis. Thus, in addition to a current phylogeny using genome-level data, some specific molecular features will be discussed as examples of how these parasites have diverged. The two subgenera of malaria parasites found in primates, Plasmodium and Laverania, reflect extant monophyletic groups that originated in Africa. However, the subgenus Plasmodium involves species in Southeast Asia that were likely the result of adaptive radiation. Such events led to the Plasmodium vivax lineage. Although the Laverania species, including P. falciparum, has been considered to share “avian characteristics,” molecular traits that were likely in the common ancestor of primate and avian parasites are sometimes kept in the Plasmodium subgenus while being lost in Laverania. Assessing how molecular traits in the primate malaria clades originated is a fundamental science problem that will likely provide new targets for interventions. However, given that the genus Plasmodium is paraphyletic (some descendant groups are in other genera), understanding the evolution of malaria parasites will benefit from studying “non-Plasmodium” Haemosporida.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plasmodium species infecting humans are part of different evolutionary lineages or clades; those lineages independently gave rise to human parasites that shared recent common ancestors with other species in nonhuman primates [1, 2]. Not surprisingly, the five parasites that primarily cause malaria in humans show biological differences in almost any stage of their life cycles [3, 4].

For example, a critical process in how Plasmodium species infect humans is the invasion of red blood cells. While Plasmodium falciparum does not show tropism toward a specific red blood cell age, Plasmodium vivax and the two species under Plasmodium ovale sensu lato (s.l.) (P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri) invade young red blood cells or reticulocytes. In contrast, Plasmodium malariae has been proposed to invade old red blood cells [3, 5,6,7]. There are also differences in the time of gametocyte production and their lifespan, which are fundamental fitness components [8, 9]. Plasmodium falciparum undergoes five stages of development in 9–12 days, the longest maturation time, and remains infectious for several days compared with other malaria parasites. On the other hand, Plasmodium vivax and the P. ovale s.l. develop dormant stages or hypnozoites that cause relapse after the primary infection; such stages are not found in P. falciparum or P. malariae [3, 10]. Another example is that P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes can adhere to the endothelium of capillaries and venules [11, 12]. This process known as sequestration is linked to severe clinical presentations that are infrequent in non-falciparum malaria [13, 14]. The traits listed above are a few out of many differences among the Plasmodium causing malaria in humans.

In addition to Plasmodium infecting humans as their primary host, there are zoonotic malaria parasites from nonhuman primates. The most recognizable is Plasmodium knowlesi from macaques in Southeast Asia [15,16,17]. However, evidence incriminates other nonhuman primate malaria species as zoonoses in that region, even causing asymptomatic infections [17,18,19]. Furthermore, anthropozoonotic malaria parasite cycles involving South American nonhuman primates have been reported [20,21,22].

The parasite species that can infect humans vary in their geographic distributions and ecological contexts. There could be a predominant species in a region or all of them [1, 23, 24]. In contrast, zoonotic and anthropozoonotic cycles have restricted geographic distributions limited by biogeographical factors involving the presence of nonhuman primates and suitable vectors [1, 20, 22]. Thus, the local Plasmodium species pool in primates (human and nonhuman) complicates malaria epidemiology to the extent of hampering elimination efforts [15,16,17, 20,21,22].

Although zoonotic species have been the focus of attention, there are at least 39 known Plasmodium in nonhuman primates worldwide; that number includes described species or detected lineages (Table 1). Several of these parasites were not a particular focus of research inquiry until recently. It can be speculated that such limited attention was due to difficulties working in nonhuman primates. Also, there was a reasonable focus on workable animal models to understand malaria biology and explore treatments or vaccines. Regardless of the factors that hindered their study, extraordinary progress has been made in the last two decades.

This review focuses on the evolution of Plasmodium in primates. Studying how distinct phenotypes, molecular adaptations, and host–parasite biocenosis emerged during the evolutionary history of Plasmodium in primates may lead to new intervention targets and a better understanding of host-parasite interactions. Indeed, there is much to be gained from comparative approaches that include nonhuman primate malaria parasites. For example, antigenic variation was first discovered in P. knowlesi [26, 27], a convergent trait found in P. falciparum later [14, 28, 29].

Here, Plasmodium diversity in primates will be considered at different levels. First, an overview of the primate malarias species diversity will be provided by following a phylogeny. Then a discussion on what is known about their host specificity will be followed by examples of how comparative genomics allow detecting putative molecular adaptations or functional differences. Finally, a discussion of the timeframes estimated for these parasites’ divergence will be provided.

Plasmodium in primates: an overview

Plasmodium species in nonhuman primates were first found in orang-utans and macaques imported to Europe between 1905 and 1907 [3, 4, 30]. A decade later, malaria parasites in African Apes were found by Eduard Reichenow [31, 32]. Unlike those parasites from Southeast Asia, the early findings in gorillas and chimpanzees were considered infections of the species found in humans [3, 33,34,35]. However, it was soon established that those were distinct species [33, 34].

As nonhuman primate malarias were discovered, parallels were established with those found in humans [4]. This search for similarities between nonhuman primate parasites and human parasites (phenetic approach) is evidenced in the book “The primate malarias,” organized by “malaria’s types” rather than by the parasites’ inferred evolutionary relationships or proposed taxonomy [3]. Nowadays, it has been demonstrated that these phenotypes are convergent traits among Plasmodium species [36,37,38,39,40], so they do not inform about the parasites’ evolutionary history. A notorious example P. malariae and Plasmodium inui, the latest species found in macaques (Table 1); they both have a 72-h periodicity (or quartan malaria) but were not considered “closely related” or sister taxa [4, 36, 37]. Nevertheless, such comparisons between human and nonhuman primate parasites were pragmatic in establishing putative models and understanding their potential disease risk to humans, acknowledging the lack of a robust evolutionary framework [3, 4].

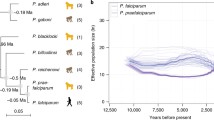

Here, Plasmodium species in primates will be discussed following their evolutionary history. The Bayesian phylogeny in Fig. 1 was estimated based on the mitochondrial (mtDNA) genome because it includes several known taxa in each clade. Although a single locus, the mtDNA genome has approximately the same AT content across Plasmodium species. Also, it is not saturated at the time scale of the events described in this phylogeny [39, 41]. Thus, these characteristics reduce the risk of model misspecification that could affect phylogenetic analyses. Importantly, the mtDNA phylogeny is concordant with the nuclear genes [38, 39], as will be discussed later.

Phylogenetic tree of Plasmodium spp. based on complete mitochondrial genomes. Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood methods yielded identical topologies; only the Bayesian tree obtained using MrBayes v3.1.2 is shown. The alignment included approximately 5800 bp of the parasites’ mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA). The values above branches are posterior probabilities. The phylogeny branches leading to human malaria parasites are colored in red

Perhaps a faulty generalization, there are three notable species radiations of Plasmodium in primates that are known of yet. One occurred in great African apes comprising the lineages that gave origin to P. falciparum, the species causing the most severe form of malaria in humans. Such clade will be referred to as Laverania as it is a monophyletic group that coincides with the subgenus proposed in the classical malaria taxonomy (Table 1, Fig. 1) [4]. Laverania includes at least seven species found in African hominids other than humans (Table 1) [2, 42,43,44]. Plasmodium falciparum and related parasites have several unique genes and gene families that set it apart from the other Plasmodium in primates, which will be revised later.

Another important clade consists of parasites found in Africa and Southeast Asia (Table 1). This monophyletic group contains Plasmodium species found in Catharine’s primates in a complex evolutionary history involving the origin of P. vivax [39, 40, 45,46,47]. For lack of a better term, these parasites will be referred to as the “vivax clade” to link them with the origin of P. vivax (Fig. 1). Among those species are parasites found in orang-utans, gibbons, macaques, and langurs. It also includes lineages found in African apes that will be generically called Plasmodium vivax-like [47, 48]. Whether one of these “vivax-like” is the African ape parasite, Plasmodium schwetzi [3, 4], cannot be determined because there is no molecular data associated with that species.

Southeast Asia species belonging to the vivax-clade are part of rapid radiation involving multiple sympatric hosts in an area that has undergone complex biogeographic processes that includes the origin of P. vivax [40, 45, 48]. A unique characteristic of this monophyletic group is that it has species with different life-history traits. In particular, there is a quartan parasite (72 h in P. inui a convergent trait with P. malariae), a quotidian (24 h cycle for P. knowlesi, unique in primates but found in avian and rodent malarias), and tertian malarias (48 h cycle common in all the other primate Plasmodium) [3]. The species differ in their tropisms toward types of red blood cells. Plasmodium cynomolgi and Plasmodium coatneyi invade reticulocytes, whereas P. knowlesi erythrocytes of all ages [3, 26]. Plasmodium knowlesi has the SICAvar gene family associated with antigenic variation, an analog (convergent trait) to the var gene family in Laverania [49]. On the other hand, P. cynomolgi, Plasmodium simiovale, and Plasmodium fieldi relapse like P. vivax; whereas P. knowlesi, P. coatneyi, and Plasmodium fragile, do not [10].

It can be hypothesized that such phenotypic diversity may allow the coexistence of multiple parasite species by reducing competition [45]. Indeed, coinfections are relatively common in macaques (individuals with more than one species of Plasmodium), and these species are all transmitted by the same vectors in each region [45, 50,51,52,53,54,55]. In that regard, it is similar to humans, where malaria parasites coinfections are relatively common but, in the human case, by species with different evolutionary histories rather than species from the same monophyletic group. Thus, considering that these rapid speciation events were linked to divergent phenotypes, it suggests adaptive radiation [45]. It is worth noting that there is no molecular information available from three species of Plasmodium described in gibbons, Plasmodium eylesi, Plasmodium jefferyi, and Plasmodium youngi [3]. It is assumed that these parasites are part of the same vivax-clade in Southeast Asia, but data from those species could change this perspective.

There are two parasites described in orang-utans that are likely part of the Plasmodium species’ radiation in southeast Asia, Plasmodium pitheci and Plasmodium silvaticum [30, 56]. They are tertian malarias like P. vivax. Although no molecular information is linked to these two species, three Plasmodium lineages from orang-utans have been reported using mtDNA (Fig. 1) and other nuclear loci. Whether those three molecular lineages include the two described species requires additional information. Nevertheless, based on the molecular evidence, the orang-utan parasites with molecular evidence are part of a clade with P. inui (Fig. 1), a quartan parasite commonly found in macaques, together with Plasmodium hylobati, a tertian parasite from gibbons [45, 46]. There are malaria parasites in African monkeys that are also part of the “vivax-clade” (Table 1). In particular, Plasmodium gonderi and another lineage that could be Plasmodium petersi (Fig. 1), but the latest has not been confirmed [57]. Plasmodium gonderi is a tertian parasite with tropism toward reticulocytes, like others in the “vivax-clade.”

Not considered part of the “vivax” or Laverania clades, there are two lineages involving sisters’ taxa of the human parasites P. malariae and P. ovale s.l. [2, 42, 58], the latest harbours two separated cryptic species, P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri [58, 59]. However, it is worth mentioning that the two P. ovale s.l. species, P. malariae, and the vivax-clade are part of a monophyletic group corresponding with the subgenus Plasmodium [25, 38, 39] (Fig. 1).

Finally, the third radiation of malaria parasites is a less-known clade of Plasmodium in lemurs that includes several putative species [25, 60]. Unfortunately, the eight described morphospecies are controversial and lack molecular data (Table 1) [25, 60]. How these parasites in lemurs radiated, their diversity, and their relationship with the continental nonhuman primate malarias are neglected issues in the research agenda on the evolution of Plasmodium. Although initially included in the subgenera Vinckeia with the rodent malarias [4], these lemur parasites may share a common ancestor with the non-Laverania primate malarias based on mtDNA (Fig. 1) [25]. If confirmed, the lemur malaria clade will also be part of a broader monophyletic group comprised of all non-Laverania primate malarias.

Plasmodium in primates: host specificity

As in other parasites, there is compelling evidence indicating host switches among primate malaria parasites through their evolutionary history [40, 42, 45, 61,62,63,64]. Host switches have fueled questions regarding where nonhuman parasites change disease risk to humans. This concern is not new [3, 65]. However, its importance was evidenced by discovering naturally infected humans with P. knowlesi in high prevalence [15]. A different problem is discussing how host specificity, or lack of it, may have driven the diversity of primate malaria parasites. Indeed, studying parasite speciation or the parasites' actual host range is different from assessing the prevalence of zoonotic infections. For example, a parasite can fail in colonizing humans because there is no human-to-human transmission. However, it could still be relevant because of its impact on disease as a zoonosis.

Classic parasite speciation models are a gradient between two processes, codivergence and host switches [66,67,68]. Codivergence involves that parasites are shared by descent while their hosts diverge because of determined biological traits [66, 69]. On the other hand, host switches imply that new malaria parasites host biocenoses change due to their ecological contexts, leading to the subsequent specialization to a new host [45, 70, 71]. In the latter scenario, geographical proximity across their hosts’ evolutionary histories is crucial to allow for opportunities for parasite transfers [45, 67, 70, 72]. This second scenario gains support wherever there are no phylogenetic concordances between host and parasite species. Considering such a framework, Plasmodium in primates involves a series of biogeographic processes where the hosts’ demographic histories limit the possibility of host-switches regionally. At the same time, there is some level of host specificity comprising specific clades of primates.

There is not a clade of gorilla versus a clade of chimpanzee parasites; thus, in that regard, cospeciation did not occur. However, there are pairs of parasites between chimpanzee and gorilla lineages in the Laverania clade that could indicate cospeciation. In particular, Plasmodium gaboni (chimpanzee) and Plasmodium adleri (gorilla) are sister taxa, and then P. reichenowi (chimpanzee) and Plasmodium praefalciparum (gorilla) are also sister taxa [73]. Unfortunately, the genomic data is still incomplete due to the absence of the bonobo parasite Plasmodium lomamiensis. However, the bonobo parasite seems to be a sister taxon of P. reichenowi found in chimpanzees [2, 43]. The divergence of bonobo and chimpanzee parasites may suggest cospeciation. Disentangling such paleobiogeographic scenarios requires additional information.

Interestingly, there is a vivax-like parasite in African apes, but no evidence indicates it can infect humans [48]. Thus, it seems that colonizing nonhuman African apes has led to new and divergent vivax-like lineages [48]. So, in this case, a host switch likely originated two different species of P. vivax-like parasites [48]. An interesting case is Plasmodium simium, as it seems to be differentiating from P. vivax populations [21]. Whether this is a case of early speciation remains to be elucidated since P. simium infects humans [20], which may facilitate introgression.

The situation is far more complex in Southeast Asia within the species in the vivax-clade. The parasites commonly referred to as “macaque malarias” [50] vary in their host specificity (Table 1). Although humans are infected, humans seem to be paratenic hosts since human-to-human transmission has not been documented [74, 75]. There is no evidence of host-switches between “macaque” and orang-utans parasites, regardless of their hosts’ overlapping distributions [45, 54, 76]. This observation is significant considering that all the species incriminated as vectors of nonhuman primate Plasmodium belong to the Anopheles (Leucosphyrus) group, and they feed on macaques and orang-utans [56, 75]. There is a lack of sampling effort in other primates, so it is premature to disregard those species as potential hosts for the so-called macaque malarias.

Nevertheless, the limited host range observed in some species (e.g., orang-utan malaria parasites) suggests patterns of concordance between parasites and particular clades of primates. Out of Southeast Asia, for example, the tertian Laverania parasites radiated and are transmitted within Homininae (Homo, Pan, Gorilla). Host specialization in malaria parasites can be selected for in some circumstances, as the data in humans and other apes suggest. For example, it can be hypothesized that following the human expansion, molecular adaptations associated with the erythrocyte invasion in P. falciparum, such as PfEBA165 and PfRH5, were selected for narrowing its host range to humans [77, 78]. Furthermore, there is no evidence of nonhuman great apes parasites infecting humans, even in close contact with infected individuals [73, 79, 80]. Likewise, the tertian species in Asian apes seem to be host-specific (Pongo, Hylobates), whereas P. ovale s.l. species are restricted to African apes (Homininae) [59, 81]. All these patterns indicate that the host ranges of primate malaria parasites likely underwent historical changes due to each host species’ demographic history, driving their population densities and spatial distributions [45]. Thus, in some contexts, specialist Plasmodium parasites may have been selected for when their hosts' populations were expanding, as seems to be the case of P. falciparum, P. vivax, and other parasites.

The case of P. malariae/Plasmodium brasilianum species deserves particular attention. This parasite shows host restriction in Africa by infecting African apes (Homininae), coinciding with the geographic region where P. malariae very likely originated [2, 42, 81]. Furthermore, there is no evidence that apes in Asia or other nonhuman primates acquire P. malariae locally. Thus, this parasite has a limited host range in the old world among Homininae. The implication is that P. malariae became a generalist (P. brasilianum) after its introduction in the New World by infecting multiple nonhuman primate species across many genera in all families of local primates.

Disease ecology’s available theory predicts the traits that introduced parasites may have to establish in a new locality. First, such parasites are generalists; second, they likely have low virulence in the natural host and should be prevalent enough to be present in the host population that introduced them into the new environment. Third, there should be suitable competent vectors in the new area. Overall, these dynamics are affected by the endemic parasite assemblage [82, 83]. Thus, it can be hypothesized that P. malariae became generalist in the New World facilitated by vectors with a broad host range, low virulence in the natural host (humans), and no endemic parasite that could compete with them.

It is worth noting that spillovers from humans to nonhuman primates are being documented in Asia and Africa. Plasmodium falciparum has been found in gorillas and chimpanzees in captivity or semi-captivity settings [73, 84, 85]. In one of those studies, the parasites were positive for chloroquine resistance mutations [85]. Likewise, there are reports of P. malariae in chimpanzees [42, 86]. The two P. ovale sub-species circulate in chimpanzees from Cameroon, low land gorillas from the Central African Republic, and bonobos [43, 64, 84, 87]. Whether this could lead to anthroponotic cycles (reverse zoonosis) is premature to say.

Estimating the phylogeny of Plasmodium in primates: from single gene trees to phylogenomics

Molecular phylogenetic analysis in malarial parasites started in the early 1990s. Like in other eukaryotic protozoa, the original locus of choice was the 18s SSU rRNA, and those studies inquired about the origins of human malarias [88,89,90,91]. Although the 18s SSU rRNA is still widely used in diagnostics, its use in phylogenetic studies has diminished within Haemosporida. In particular, the occurrence of non-concerted evolution among stage-specific expressed paralogs makes interpreting gene trees in terms of species trees challenging [92, 93].

Other early phylogenetic studies used the gene encoding the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) [94]. The CSP is an antigen expressed on the surface of the sporozoite, the infective stage inoculated by the vector into the vertebrate host. It has been a target of pre-erythrocytic vaccines because of its critical functions in the first steps of the parasite infection. However, it is under selective pressure for accumulating polymorphism with a tandem repeat motif (low complexity region) that does not allow its full-length alignment [94]. Such characteristics are not suitable for inferring species trees. Still, it has been appropriately used in some contexts considering the extensive database of sequences available [15].

Finally, the parasite’s mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) was used in a haemosporidian phylogeny [36] to overcome the shortcomings of the two first loci. Overall, it corroborated early observations. A commonality in such early studies (csp, cytb, and 18S SSU rRNA) was that they aimed to infer the evolutionary history of known taxa. Perhaps their more significant conclusion was that the human malarias emerged independently. Nowadays, phylogenomic analyses can take advantage of the genomic data available.

A common problem when inferring the species tree from genome-level data is gene tree conflicts because of incomplete lineage sorting, differences in selection constraints, changes in the model of nucleotide substitution across loci, among other factors. As a result, there are multiple approaches to dealing with species trees versus gene trees. It is worth mentioning that the taxa limit phylogenomic analyses with the lower quality genome (e.g., shorter sequences or less genome coverage). It can only use single-copy genes and with clear orthologs across the species under consideration.

Figure 2 shows a consensus phylogeny that incorporates 1028 single-copy genes; orthologous groups were inferred de novo by using OrthoFinder [95] on all available Plasmodium genomes from mammals and Hepatocystis [81, 96,97,98,99]. Two Plasmodium species from birds with genomic data, Plasmodium gallinaceum and Plasmodium relictum, were used to estimate the root of the primate-rodent malarias [100]. The species tree was inferred under the multi-species coalescent model implemented in ASTRAL III [101]; this method finds the species tree that agrees with the largest quartet trees from a set of gene trees. The gene trees were estimated using IQTREE [102] under the best substitution model that fit each gene alignment. It is worth mentioning that an identical topology was obtained by concatenating genes. Overall, the phylogeny recovers the major clades made evident by early studies and is consistent with the mtDNA phylogeny presented in Fig. 1, with a few differences that will be discussed below.

Phylogenomic analyses of the primate malarias using the available genomes. Consensus phylogeny on 1028 single-copy orthologous genes under the multi-species coalescent model implemented in ASTRAL III. Plasmodium gallinaceum and Plasmodium relictum were used as an outgroup to estimate the root of the primate malarias

As expected, the Laverania subgenus relationships presented here (Fig. 2) are congruent with those previously reported [2, 97, 98]. It is a monophyletic group separated from the other Plasmodium found in mammals. Plasmodium vivax-P. vivax-like lineage (vivax lineage for short) is within the radiation of the parasites referred to as the Africa-Asian radiation, as previously proposed for P. vivax [38,39,40, 45, 48, 61, 98]. The primary difference is that the vivax lineage shares a more common ancestor with P. inui rather than P. cynomolgi [38,39,40, 46, 103].

Plasmodium cynomolgi, among the parasites found in Southeast Asia, has been widely accepted as the species that shared the most recent common ancestor with the vivax lineages [3, 39, 40, 91, 99]. This notion is supported by biological traits and early phylogenetic analyses using single-gene approaches (Fig. 1). Thus, the P. inui–P. vivax lineage relationship could result from limited sampling in terms of species with available genomes, particularly considering the fast cladogenesis of these species. Indeed, there is no genomic data from many species of parasites from gibbons or orang-utan. Those Asian ape parasites species share a common ancestor with P. inui based on the mitochondria genome data [45, 46]. Finally, it must be noted that preliminary data indicates great diversity within P. cynomolgi and P. inui [3, 45, 46]. Sampling across divergent “strains” would likely improve phylogenetic inferences about the relationship between the P. vivax lineage and parasites found in macaques.

The position of P. gonderi is also worth noticing. The phylogeny using genomic data (Fig. 2) concord with the mitochondrial phylogeny (Fig. 1) and several other studies [36, 38, 40, 62], but differs from other phylogenomic studies where the vivax lineage appears as a sister clade to the other macaque parasites [2]. Although the relative position of Hepatocystis is consistent with previous studies [36, 38, 98], its inclusion may have changed the relative position of P. gonderi in this analysis when compared to others [2]. This observation highlights the issue that the sampled taxa, not only loci, should be considered when comparing incongruences between phylogenetic studies. Finally, it is worth noting that there is at least one Plasmodium species found in mandrills that shares a common ancestor with P. gonderi (Fig. 1). No genomic data is available from that parasite.

Based on the phylogenies presented in Figs. 1 and 2, it is reasonable to state that the phylogenies support an origin of P. vivax as part of the parasite radiation in Asia [40, 62]. Such observation will be consistent with an early introduction of the vivax-lineage from Southeast Asia into Africa, giving origin to the two species known in African apes, P. vivax in humans and P. vivax-like in chimpanzees [48]. Interestingly, in the phylogeny based on genome data presented here (Fig. 2), the subgenus Plasmodium is a monophyletic group, differing from the phylogenies estimated by others [2, 98]. The phylogeny also is consistent with P. malariae originating in Africa, as indicated by the presence of P. malariae-like [42, 81]. This parasite could be called Plasmodium rhodaini, if it ever re-described, to honor the old species name. A less explored clade is one where P. ovale and P. malariae share a common ancestor with all other primate malarias, including the poorly sampled parasites in lemurs [25]. Unfortunately, the genomic data is incomplete in terms of taxa.

A few taxonomic notes

Whereas an issue discussed in taxonomy, delimiting parasite species has repercussions in health and policy [4, 104], e.g., differential diagnostics. The goal of a taxonomy is to integrate information and make biological predictions about the organisms considered part of particular taxa. Thus, discovering species and having them on record are aspects of critical importance [4].

Plasmodium species are described using life histories and morphological traits on the parasite blood stages observed in Giemsa-stained films in a light microscope. Unfortunately, even unrelated species can look alike, as evidenced by P. knowlesi in humans that can be confused with P. falciparum or P. malariae [105]. Nevertheless, there were enough traits to set species apart in parasites from Southeast Asia [3], those were reproduced in molecular studies. In contrast, all initial reports of parasites in African apes found them indistinguishable from Plasmodium in humans.

Thus, the host was used for species delimitation and identification in several cases [35]. Experimental infections were used wherever possible [3], but such a practice cannot be scaled up, and nowadays is ethically and scientifically questionable for taxonomic porpoises. However, after the parasite’s mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) was used in a haemosporidian phylogeny [36], molecular lineages started to be used as a proxy to discovering and delimiting species [42,43,44, 47, 106]. Decades after the original observation of Plasmodium in African apes, such mitochondrial loci allowed the discovery of distinct molecular lineages circulating among African apes that were independently reported and reproducible [2, 42,43,44, 47]. Such data indicated active transmission. Still, the argument was made against recognizing those Plasmodium species because there was a lack of certainty about their hosts. The sexual stages required to infect the mosquito vector were not documented in the African apes [107]. Perhaps an extreme case, Plasmodium species in African Apes have generated an unusual situation where taxa with complete genomes may not have been “formally described.” Thus, primate malaria parasites highlight the problems describing and delimiting Plasmodium species.

Although using molecular data in the absence of morphology remains a contentious issue [85, 107], primate malarias have shown that single-gene criteria can first approximate species, particularly if multiple detections indicate active transmission and the data is of good quality.

Early molecular phylogenetic studies showed that the genus Plasmodium is not a monophyletic [36], an observation that has been confirmed ever since [25, 38, 39, 45, 108, 109]. Comparisons across phylogenetic analyses are not simply because of differences in taxon sampling and the loci used. Nevertheless, all molecular phylogenies show that Plasmodium is not monophyletic [25, 36, 38, 39, 45, 108, 109]. Indeed, the Plasmodium clade includes other genera found in mammals, such as Polychromophilus (Chiropteran), Nycteria (Chiropteran), and Hepatocystis (Chiroptera and Primates). It is worth noticing that, historically, the adoption of the genus Plasmodium was pragmatic [3, 4].

A critical early observation was that P. falciparum and P. reichenowi shared several features with avian parasite species, setting them apart from the other species infecting humans [3, 110,111,112]. Such discrepancies led to several proposed genera [3]. After an exhaustive review of the evidence, it was recommended that all human malaria parasites belong to the genus Plasmodium. The type species was settled in P. malariae. A separate subgenus, Laverania, was kept for the human parasite P. falciparum and P. reichenowi to set them apart from other primate malaria parasites that were classified under the subgenus, Plasmodium. Since taxonomy should integrate data into taxa, the generalization made 70 years ago was that the species that can produce malaria in humans belong to the genus Plasmodium (Opinion 283, IZCN cited in [3]). This recommendation was held even when many life-history traits that make a parasite a “Plasmodium” are not unique to the genus.

The elephant in the room is whether to revise Plasmodium and other Haemosporida genera based on molecular evidence. Unfortunately, given the practical importance of the current taxonomy, the problem is unlikely to be addressed soon. It is worth noticing that the two subgenera, Plasmodium and Laverania, seem to reflect those species’ biology. Furthermore, if additional evidence support that lemur parasites share a common ancestor with the non-Laverania primate malarias, this will lead to a monophyletic group of non-Laverania primate parasites that perhaps can be placed in the subgenus Plasmodium. Indeed, there was a rationale behind the subgenera while using the genus Plasmodium as an umbrella [4].

Laverania and Plasmodium subgenus

Differences between these two clades of parasites fueled hypotheses about their distinct evolutionary histories. One that received attention was a “recent” origin of P. falciparum due to a host switch from an avian host, a hypothesis rooted in some particular interpretation of data, well before any formal phylogenetic analyses. It was argued that it explained the high virulence of P. falciparum compared to other human malarias [4, 56]. It lacked a precise timeframe of what was meant by “recent,” the term translated as “newer than the other human malaria parasites,” and the discussion seldom considered P. reichenowi.

However, virulence was not the more critical evidence. Avian malaria parasite species share morphological features with P. falciparum and P. reichenowi, such as falciform gametocytes [111, 112], placing them apart from P. vivax and P. malariae. Such resemblance drove the research agenda in avian malarias as they were noticed by Laveran (cited by [110]), leading to important discoveries such as mosquitoes as malaria vectors by Ross in 1898 using the avian parasite P. relictum as a model. Also, host switches were deemed common in avian malarias since morphologically indistinguishable species were found in hosts across avian families [4, 110], as modern studies have confirmed. Furthermore, some avian parasites were able to infect human erythrocytes experimentally [113]. Finally, early molecular evidence indicated that P. falciparum has similar A-T content in their genomes than avian and rodent malarias [114]. Thus, given the limited number of species with molecular data and the lack of a suitable outgroup, the tree topology of early phylogenetic studies was interpreted in such a context [88].

Although a spillover avian-origin for P. falciparum has been clearly rejected [2, 42,43,44, 61, 63, 89,90,91, 94, 97], the data separating Laverania from the Plasmodium subgenus remains. Indeed, as will be shown later, molecular traits are kept or lost in either one of these two subgenera compared to the common ancestor shared with avian parasites.

It is worth noticing that genome architecture features separate the subgenera Laverania and Plasmodium, including A + T content, patterns of codon usage, and the distribution of low-complexity regions [115,116,117]. Furthermore, among the best-known molecular adaptations separating Laverania from Plasmodium are gene families involved in antigenic variation [14, 49], such as the var gene family. Even gene families believed initially to be found across Plasmodium [49], such as Plasmodium-interspersed repeat proteins (pir), do not have clear orthologs between the two clades of primate malarias [118]. However, here, the discussion will be limited to specific genes and loci without attempting an exhaustive review.

Recently, the PfRH5-PfCyRPA-PfRipr (RCR) complex has been discovered in P. falciparum; it is essential in the invasion of the red blood cell and a target for the next generation of anti-falciparum vaccines [119, 120]. The PfRH5-PfCyRPA-PfRipr (RCR) complex is a protein trimer formed on the surface of the P. falciparum merozoite that binds to the host receptor basigin in the erythrocyte. The cell biology aspects of the complex have been revised elsewhere [119,120,121]. Here, what matters is that orthologs of PfRH5 are found only in Laverania, but orthologs of PfCyRPA and PfRipr are present in all primate malarias [121]. Figure 3 shows Bayesian phylogenetic analyses of the three genes encoding the proteins of the complex.

Evolution of the genes encoding the proteins in the RCR complex. Bayesian phylogenies for the proteins in the RCR complex were obtained using MrBayes v3.1.2. The two clades compared to assess differences in the strength of natural selection are indicated with different colors. In blue was the tested group corresponding with those closely related to P. vivax; the Laverania used as references are highlighted in green

The PfRipr and PfCyRPA orthologs are essential in P. knowlesi, but they do not form a complex with each other [121]. Thus, the limited experimental evidence indicates that cyrpa and ripr orthologs have different functions in the two subgenera of primate malaria parasites. A simple and perhaps crude test of such functional differences can be exploring whether Laverania and the Asian species of the vivax-clade, where P. knowlesi and P. vivax are, have different selective regimens. In particular, by using phylogenetic-codon-based tests such as RELAX [122], changes in the selective regimens may indicate differences in function between the two clades. Using the vivax-clade as a test against the Laverania as a reference, this approach found evidence consistent with changes in how natural selection operates between the two groups. In particular, the vivax-clade shows relaxation for cyrpa gene when compared to P. falciparum (k = 0.62, p = 0.01). Relaxation in the strength of selection indicates a reduction in the intensity of natural selection in the test clade when compared against the reference, which may indicate a change in function. Ripr orthologs, on the other hand, show intensification in P. vivax when compared to P. falciparum (k = 14.81, p < 0.001). Notice that the reciprocal tests, Laverania as clade being tested and the vivax-clade as a reference, lead to the same results with different signs, so it is not worth commenting on them.

There are other examples among the proteins involved in the invasion of the red blood cell by merozoites, particularly the GPI-anchored proteins, that are known to be essential. Several genes have studied the issues regarding how natural selection may operate [85, 103, 123,124,125]. Here, the genes encoding the merozoite surface proteins 1 (msp1) and 2 (msp2) will be discussed as they have been the focus of studies for decades.

The gene encoding msp1 has a paralog in P. vivax (Pvmsp1p) that is highly conserved worldwide among populations of these parasites. The primary structure of Pvmsp1p protein contains a putative GPI anchor attachment signal and double epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains at the C terminus. This paralog is found in all the parasites in the subgenus Plasmodium and the two avian parasites included as outgroup (Fig. 4), but it was lost in the Laverania subgenus. Evidence indicates that this paralog may be part of a Duffy-independent pathway in P. vivax [126], so it may be an important mechanism to invade the red blood cell, as the conservation in multiple species indicates. In contrast, the gene encoding msp1 is found in all Plasmodium species [103, 123, 124]. The msp1 in P. falciparum is part of protein complexes with overlapping functions while interacting with human erythrocytes [127]. However, proteins that are part of those complexes in P. falciparum, such as Pfmsp6 and Pfmsp3, only have orthologous in Laverania. It is worth notice what is called “msp3” in the vivax-clade are not orthologous with the genes with the same name in Laverania [128]. Thus, the lack of orthologous proteins that form such complexes is indicative of the differences between the two subgenera, even around essential functional proteins.

Evolution of the gene encoding the merozoite surface protein 2. A synteny map of the msp2 region is depicted. A msp2 ortholog is found in the avian parasites’ genomes. A Bayesian phylogeny obtained using MrBayes v3.1.2 on orthologous genes is provided. The branches with the two allelic forms in P. falciparum are colored in red

The merozoite surface protein 2 (msp2) is an abundant GPI-anchored protein of P. falciparum that is expressed in the merozoite [123]. The msp2 is an intrinsically disordered protein due to its variable central region. Indeed, the msp2 polymorphism is still being used to characterize P. falciparum populations in molecular epidemiologic investigations [129]. Nevertheless, the N-terminal and C-terminal regions are highly conserved. All msp2 alleles belong to either one of two allelic families, 3D7 and FC27, distinguished by their central variable regions [85]. These two allelic forms appear separated in the msp2 Bayesian phylogeny depicted in Fig. 5. The gene encoding msp2 is considered a Laverania specific gene since orthologs have not been found in other primate malarias [85]. Figure 5 shows the synteny of the orthologous genes encoding msp2; as expected, when only studying the Plasmodium in mammals, this gene can only be found in the Laverania clade. However, an ortholog encoding msp2 is observed in the avian genomes. The implications are that, unlike the case of the msp1 paralog, the Laverania clade kept msp2 but that it was lost in the other Plasmodium infecting mammals.

Evolution of the genes encoding the merozoite surface protein 1 and its paralog. A synteny map of the msp1 region is depicted. Notice that an ortholog of the msp1 paralog originally described in P. vivax is found in the genomes of avian parasites. A Bayesian phylogeny on orthologous genes obtained using MrBayes v3.1.2 is provided. The branches with the two msp1 allelic forms in P. falciparum are colored in red. All the lineages leading to extant human malarias are indicated in red

The differences between the subgenera are not limited to blood stages. Recently, differences between the two subgenera have been made evident in the genes encoding chitinases. These genes are critical in releasing the ookinete in the vector, and this is perhaps the first documented difference in such a stage of the parasite life cycle [130]. There are differences in the chitinases between the vivax-clade and the Laverania. Species having two forms of chitinase seem to be an ancestral trait shared with the avian parasites. One form is preserved in Laverania, while the other is in Plasmodium subgenus and rodent malarias. However, Plasmodium ovale s.l. (both species) keeps the two forms of chitinases like in the avian malarias. Furthermore, P. malariae has one functional chitinase and a pseudogene [130]. Overall, this pattern indicates that losing one of the chitinases in P. vivax and related species is a relatively recent event in the evolution of the clade that includes all non-Laverania parasites [130].

Molecular clock: timing the origin of the primate malaria clades

Considering the differences between the two Plasmodium clades in primates, when did they diverge? Numerous studies on time inferences have focused on P. vivax and P. falciparum [40, 97, 131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138]. An average mutation rate is usually estimated or assumed [97, 132, 134,135,136,137]. Such mutation rates are then used to infer the demographic histories of P. vivax or P. falciparum but do not address the genus’ origin. Importantly, those studies show a broad range of possible scenarios, most of which pointed to an expansion of those parasites following the human populations.

Perhaps a study that defers from the others used a tip-dating-based approach on an ancient genome of P. vivax [138], a commonly used method in viruses. An assumption is that the time of collection informs about the mutation rate, so population structures before the sampling of the sequences are not supposed to introduce a bias. In this case, an isolate collected in Europe between 1942 and 1944 informs about the divergence concerning those in the Americas. The authors found a significant correlation between time of collection and divergence between isolates; however, it seems explained basically by two points, the ancient DNA isolate and the samples from North Korea. Only a few of the available isolates from the Americas were considered, and the possibility that the isolate collected in Europe was an introduction of P. vivax lineage from the Americas into Europe was not discussed. Regardless of this, it is an approach that seems interesting to explore and discuss further because it is the only one that may place P. vivax populations expanding in historical times [48, 132, 134, 135].

In contrast to the studies discussed above, there are few studies on the origin and radiation of the primate malaria parasites. Like when inferring demographic histories, various assumptions and data lead to different predictions. The first set of assumptions is calibrating the clock via time constraints (calibration points or time references). Primary calibration constraints, or direct evidence of a given event used as a reference, are independently provided from fossil data and known biogeographic events in the extant taxa [139]. There is almost no evidence of malarial parasites in the available fossil record, so host data is often used to inform the models [25, 131]. Those are secondary calibrations as they provide indirect evidence involving additional assumptions. By their very nature, those are problematic, but there seems no way of avoiding them. Thus, calibration constraints should be carefully described to be tested by others [25, 140], understanding that such analyses simply make some scenarios more parsimonious than others.

The second set of assumptions involves how to model the rate of evolution, constant or heterogeneous. It has been long known that a constant rate of evolution model (strict molecular clock) is rejected when including more distant species [139, 141]. Nevertheless, variations of a single rate of evolution or some form of constant rate have been widely used in Plasmodium.

Perhaps the first modern molecular timing analyses were carried out assuming a strict clock model on the mitochondrial genome. The assumption of constant rate was statistically rejected [142]. As an ad hoc approach, a rate was estimated on a subset of species where the strict clock was not rejected. Then the rate was extrapolated on the other species [142]. The origin of the genus was estimated to be 22.2–41.6 Ma (million years ago), and the time to the common ancestor between Plasmodium in primates and rodents was estimated to be 18.3–34.7 Ma. The origin of the Catarrhini primate malarias was estimated to be 25.7 Ma [23.1–28.3] under one of the scenarios. This estimate overlaps with fossils that place such events between 24 and 34 Ma [143]. The time estimates were younger than their hosts for all the other clades, which could be interpreted as host-switches. However, in addition to the assumption of constant rate, the sampling of taxa could have also been a factor since most species were primate malaria parasites.

A modality of a constant rate of evolution estimated the time of origins of a few Plasmodium species by using genomic level data of coding protein genes [144]. In contrast to the previous study [142], this approach estimated substantially older times for the origin of Plasmodium in primates and rodents. The method proposed calculated relative times against a reference divergence between a pair of species. Plasmodium vivax and P. knowlesi were used as a reference in the original study, but changing the pair of species used was not explored. Nevertheless, the method assumes a constant rate of evolution for each ortholog group of single-copy protein genes across species, not a single rate for all proteins. Under these assumptions, the split between the human parasite P. falciparum and the rodent parasite Plasmodium yoelii was 6.1 times older than the split of the chimpanzee parasite P. reichenowi from the human parasite P. falciparum [144]. Thus, estimates depend on how to convert such relative times.

Although having a single and constant mutation rate seems desirable, it is not a robust approach [139, 141, 145]. Furthermore, if such rates are estimated using ad hoc methods, the analyses are difficult to replicate. Thus, mainstream molecular dating approaches are desirable because different scenarios, methods, and assumptions can be compared.

Overall, given the data, Bayesian methods incorporate prior knowledge to estimate a posterior distribution in times and a phylogeny [141]. Priors include the values used as calibrations and modeling the rate heterogeneity and substitution models. Multiple calibrations do not imply that they all have the same effect [146], so it is important to explore different scenarios. Bayesian methods also model rate heterogeneity; the two basic models assume autocorrelation or independence. In the autocorrelation model, evolutionary rates are correlated by descent because of similarities between ancestral and descendent species [139, 141]. The independent rate variation model, on the other hand, assumes that rates vary throughout the tree following a probability distribution but are not affected by ancestry [139, 141]. Those models of evolutionary rate variation could affect estimates in particular data sets and should be compared whenever possible.

It is also noted that adding species without calibration likely increases the variance in time estimates because they may add heterogeneity in the rates [139, 141]. On the other hand, more loci may be beneficial if they have congruent phylogenetic signals, are not saturated, share patterns of rate variation across lineages, and do not require different substitution models (e.g., similar GC content). The latest is challenging to accomplish in Plasmodium genus because of the differences in GC content [115], but the mitochondria and apicoplast genomes offer an alternative [39, 147]. Of the two, the mitochondria have been widely used in such molecular clock studies.

A first attempt to explore alternative scenarios (more than a single evolutionary rate) used two different calibrations within primates [25]. This study also compared two Bayesian methods, one that assumed autocorrelation and the other independent rates. The estimates with the autocorrelation model yielded slightly older times than the independent rate models. However, given the phylogeny's limited species sampling, the credibility intervals of the estimated times between the two methods overlapped. The study found that there was some overlap with the estimates of Hayakawa et al. [142]. The novelty of this study was that it used scenarios that could explain the origin of the parasite in lemurs to validate the time estimates obtained by using separated calibrations [25]. These scenarios were further investigated, considering different calibrations and assumptions in rodent malarias [148], producing similar results.

An expanded phylogeny incorporating 102 mitochondrial genomes was constructed, including data from avian species parasites of the genera Leucocytozoon, Haemoproteus, and Plasmodium [39, 149]. It was found that different models of evolutionary rate variation across lineages, independent or autocorrelated, affect time estimates, particularly in avian clades [39]. Overall, the study estimated that the time of origin of Plasmodium in primates and rodents was approximately 45 Ma. Unlike early studies, the P. reichenowi and P. falciparum split were not included as calibration, but it is estimated around 6 Ma (4–8.4 Ma), coinciding with the Homo-Pan common ancestor. These time estimates remind consistent even when introducing a genus sharing a recent common ancestor with Plasmodium as is Haemocystidium in reptiles [149].

A limitation in all mitochondrial studies is the lack of important gorilla lineages. The sequences available from this organelle from several ape malarias are too short, so their inclusion increases the uncertainty in time estimates [25]. The additional problem is that the mitochondrial genome, as described earlier, undergoes different selective regimes correlated with the families of vector species [39]. This concern is mitigated because all mammalian malarias are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, and all calibrations used are within primate malarias. Still, it is important to include other loci as they become available.

Although these studies used secondary calibrations [25, 39, 149], it was found that the calibration points were internally consistent. That is, removing one calibration does not lead to incongruent time estimates. The times’ estimates seem to be consistent even when including a calibration out of the primate-rodent malaria clade, as is the origin of the Plasmodium found in ungulates [39, 149]. Therefore, given the data, these time priors provide a plausible framework for the timing primate malarias. Nevertheless, the best way to move the field forward is to seek additional calibration constraints, increase the number of loci and improve the sampling of taxa.

What has been learned about the time of the radiation of primate malarias? It seems that the two clades of primate malaria parasites, those under the subgenera Plasmodium and Laverania, diverged early on, with the origin of Catarrhini primates [143]. Considering the evolutionary histories of their extant hosts, the origins of these two clades likely took place in Africa. How this relates to the other none-Plasmodium genera that evolved intertwined with these two primate clades is an issue that needs to be investigated.

Conclusions

Although a challenge for control and elimination, the biodiversity of malarial parasites in primates makes this a unique model for those interested in the evolutionary biology of parasites and the use of comparative approaches. Indeed, to those interested in particular molecular adaptations or understanding metabolic pathways, comparing distinct Plasmodium species that still have common (and sometimes analogous) traits allows placing discoveries in a general evolutionary context.

The evidence indicates that host-switches are common; however, there seems to be some level of host-specificity that, together with biogeographical processes, can explain the observed diversity of primate malarias. The two clades that include primate malarias diverged early in the evolution of their hosts. Such early divergence translates into traits comprising everything from single genes to gene families. Even when using subgenera is not practical in several contexts, they remind us of the differences between the primate malaria clades in a taxonomical framework that is unlikely to be changed soon.

The molecular evidence supports an African origin for the two clades of primate malaria parasites with a species radiation in Southeast Asia from lineages that originated in Africa, likely following their hosts’ populations expansions. Such cladogenesis is consistent with adaptive radiation as several phenotypes emerged de novo.

Timing the evolution of primate malarias requires additional data; however, the available estimates offer a framework consistent with the phylogeny and biogeography of these parasites’ hosts. Although consistency does not make these times estimates correct, it is a hypothesis to be tested as more species and data are included.

A pending matter in primate malaria biodiversity is characterizing those parasites found in lemurs and gibbons. Understanding how the molecular adaptations found in the primate malaria clades originated is of critical importance. Answering such questions will require scaling up comparative genomic studies to include more malaria parasite species from nonhuman primates and other Haemosporida genera that share a common history with what is known as the genus Plasmodium s.l. In conclusion, paraphrasing Dr. William (“Bill”) Collins, an authority in primate malaria parasites and one of the authors of the primate malarias book [3], “we learn from all the parasites.”

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 18s SSU rRNA:

-

Structural RNA for the small subunit of ribosomes

- CSP:

-

Circumsporozoite protein

- cytb :

-

Mitochondrial cytochrome b gene

- IZCN:

-

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

- Ma:

-

Million years ago

- msp1 :

-

Merozoite surface protein 1

- msp2 :

-

Merozoite surface protein 2

- msp3 :

-

Merozoite surface protein 3

- PfRH5:

-

Reticulocyte Binding Protein Homologue 5 in P. falciparum

- PfCyRPA:

-

Cystine-Rich Protective Antigen in P. falciparum

- PfRipr:

-

Merozoite Rh5 interacting protein in P. falciparum

- Pfmsp6 :

-

Merozoite surface protein 6 in P. falciparum

- s.l.:

-

Sensu lato

References

Escalante AA, Pacheco MA. Malaria molecular epidemiology: an evolutionary genetics perspective. Microbiol Spectr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.AME-0010-2019.

Sharp PM, Plenderleith LJ, Hahn BH. Ape origins of human malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2020;74:39–63.

Coatney GR, Collins WE, Warren M, Contacos PG. The primate malarias. 1st ed. Bethesda: US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 1971.

Garnham PCC. Malaria parasites and other Haemosporidia. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1966.

Neveu G, Lavazec C. Erythroid cells and malaria parasites: it’s a match! Curr Opin Hematol. 2021;28:158–63.

Gruszczyk J, Kanjee U, Chan LJ, Menant S, Malleret B, Lim NTY, et al. Transferrin receptor 1 is a reticulocyte-specific receptor for Plasmodium vivax. Science. 2018;359:48–55.

Hang JW, Tukijan F, Lee EQH, Abdeen SR, Aniweh Y, Malleret B. Zoonotic malaria: non-Laverania Plasmodium biology and invasion mechanisms. Pathogens. 2021;10:889.

Sinden RE. Sexual development of malarial parasites. Adv Parasitol. 1983;22:153–216.

Bousema T, Drakeley C. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:377–410.

Cogswell F. The hypnozoite and relapse in primate malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:26–35.

Bernabeu M, Danziger SA, Avril M, Vaz M, Babar PH, Brazier AJ, et al. Severe adult malaria is associated with specific PfEMP1 adhesion types and high parasite biomass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3270–9.

Brazier AJ, Avril M, Bernabeu M, Benjamin M, Smith JD. Pathogenicity determinants of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum have ancient origins. mSphere. 2017;2:e00348-16.

Turner L, Lavstsen T, Berger SS, Wang CW, Petersen JEV, Avril M, et al. Severe malaria is associated with parasite binding to endothelial protein C receptor. Nature. 2013;498:502–5.

Moxon CA, Gibbins MP, McGuinness D, Milner DA, Marti M. New insights into malaria pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2020;15:315–43.

Singh B, Sung LK, Matusop A, Radhakrishnan A, Shamsul SS, Cox-Singh J, et al. A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infections in human beings. Lancet. 2004;363:1017–24.

Yusof R, Ahmed MA, Jelip J, Ngian HU, Mustakim S, Hussin HM, et al. Phylogeographic evidence for 2 genetically distinct zoonotic Plasmodium knowlesi parasites, Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1371–80.

Imwong M, Madmanee W, Suwannasin K, Kunasol C, Peto TJ, Tripura R, et al. Asymptomatic natural human infections with the simian malaria parasites Plasmodium cynomolgi and Plasmodium knowlesi. J Infect Dis. 2019;219:695–702.

Raja TN, Hu TH, Kadir KA, Mohamad DSA, Rosli N, Wong LL, et al. Naturally acquired human Plasmodium cynomolgi and P. knowlesi infections, Malaysian Borneo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1801–9.

Kotepui M, Masangkay FR, Kotepui KU, Milanez GDJ. Preliminary review on the prevalence, proportion, geographical distribution, and characteristics of naturally acquired Plasmodium cynomolgi infection in mosquitoes, macaques, and humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:259.

Brasil P, Zalis MG, de Pina-Costa A, Siqueira AM, Júnior CB, Silva S, et al. Outbreak of human malaria caused by Plasmodium simium in the Atlantic Forest in Rio de Janeiro: a molecular epidemiological investigation. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1038–46.

de Oliveira TC, Rodrigues PT, Early AM, Duarte AMRC, Buery JC, Bueno MG, et al. Plasmodium simium: population genomics reveals the origin of a reverse zoonosis. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:1950–61.

Lalremruata A, Magris M, Vivas-Martínez S, Koehler M, Esen M, Kempaiah P, et al. Natural infection of Plasmodium brasilianum in humans: man and monkey share quartan malaria parasites in the Venezuelan Amazon. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1186–92.

Price RN, Commons RJ, Battle KE, Thriemer K, Mendis K. Plasmodium vivax in the era of the shrinking P. falciparum map. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:560–70.

Guerra CA, Snow RW, Hay SI. Mapping the global extent of malaria in 2005. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:353–8.

Pacheco MA, Battistuzzi FU, Junge RE, Cornejo OE, Williams CV, Landau I, et al. Timing the origin of human malarias: the lemur puzzle. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:299.

Miller LH, Chien S. Density distribution of red cells infected by Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium coatneyi. Exp Parasitol. 1971;29:451–6.

Brown KN, Brown IN. Immunity to malaria: antigenic variation in chronic infections of Plasmodium knowlesi. Nature. 1965;208:1286–8.

Hommel M, David PH, Oligino LD, David JR. Expression of strain-specific surface antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Parasite Immunol. 1982;4:409–19.

Hommel M, David PH, Oligino LD. Surface alterations of erythrocytes in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Antigenic variation, antigenic diversity, and the role of the spleen. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1137–48.

Garnham PCC, Rajapaksa N, Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R. Malaria parasites of the orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus). Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1972;66:287–94.

Reichenow E. Parásitos de la sangre y del intestino de los monos antropomorfos africanos. Bol Real Soc Espan Hist Nat Secc Biol. 1917;17:312–32.

Blacklock B. Plasmodium reichenowi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1926;20:145–145.

Bray RS. Studies on malaria in chimpanzees. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:20–4.

Blacklock B, Adler S. A parasite resembling Plasmodium falciparum in a chimpanzee. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1922;16:99–106.

Christophers R. Malaria from a zoological point of view. Proc R Soc Med. 1934;27:991–1000.

Escalante AA, Freeland DE, Collins WE, Lal AA. The evolution of primate malaria parasites based on the gene encoding cytochrome b from the linear mitochondrial genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8124–9.

Kissinger JC, Collins WE, Li J, McCutchan TF. Plasmodium inui is not closely related to other quartan Plasmodium species. J Parasitol. 1998;84:278–82.

Galen SC, Borner J, Martinsen ES, Schaer J, Austin CC, West CJ, et al. The polyphyly of Plasmodium: comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of the malaria parasites (Order Haemosporida) reveal widespread taxonomic conflict. R Soc Open Sci. 2018;5:171780.

Pacheco MA, Matta NE, Valkiünas G, Parker PG, Mello B, Stanley CE, et al. Mode and rate of evolution of haemosporidian mitochondrial genomes: timing the radiation of avian parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:383–403.

Escalante AA, Cornejo EC, Freeland DE, Poe AC, Durrego E, Collins WE, et al. A monkey’s tale: the origin of Plasmodium vivax as a human malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1980–5.

Pacheco MA, Cepeda AS, Bernotienė R, Lotta IA, Matta NE, Valkiūnas G, et al. Primers targeting mitochondrial genes of avian haemosporidians: PCR detection and differential DNA amplification of parasites belonging to different genera. Int J Parasitol. 2018;48:657–70.

Krief S, Escalante AA, Pacheco MA, Mugisha L, André C, Halbwax M, et al. On the diversity of malaria parasites in African apes and the origin of Plasmodium falciparum from bonobos. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000765.

Liu W, Sherrill-Mix S, Learn GH, Scully EJ, Li Y, Avitto AN, et al. Wild bonobos host geographically restricted malaria parasites including a putative new Laverania species. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1635.

Ollomo B, Durand P, Prugnolle F, Douzery E, Arnathau C, Nkoghe D, et al. A new malaria agent in African hominids. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000446.

Muehlenbein MP, Pacheco MA, Taylor JE, Prall SP, Ambu L, Nathan S, et al. Accelerated diversification of nonhuman primate malarias in Southeast Asia: adaptive radiation or geographic speciation? Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:422–39.

Pacheco MA, Reid MJCC, Schillaci MA, Lowenberger CA, Galdikas BMFF, Jones-Engel L, et al. The origin of malarial parasites in orangutans. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34990.

Liu W, Li Y, Shaw KS, Learn GH, Plenderleith LJ, Malenke JA, et al. African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3346.

Daron J, Boissière A, Boundenga L, Ngoubangoye B, Houze S, Arnathau C, et al. population genomic evidence of Plasmodium vivax Southeast Asian origin. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabc3713.

Frech C, Chen N. Variant surface antigens of malaria parasites: functional and evolutionary insights from comparative gene family classification and analysis. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:427.

Fooden J. Malaria in macaques. Int J Primatol. 1994;15:573–96.

Gamalo LE, Dimalibot J, Kadir KA, Singh B, Paller VG. Plasmodium knowlesi and other malaria parasites in long-tailed macaques from the Philippines. Malar J. 2019;18:147.

Li MI, Mailepessov D, Vythilingam I, Lee V, Lam P, Ng LC, et al. Prevalence of simian malaria parasites in macaques of Singapore. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009110.

Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S, Thongaree S, Seethamchai S, Grynberg P, Hughes AL. Ecology of malaria parasites infecting Southeast Asian macaques: evidence from cytochrome b sequences. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:3466–76.

Amir A, Shahari S, Liew JWK, de Silva JR, Khan MB, Lai MY, et al. Natural Plasmodium infection in wild macaques of three states in peninsular Malaysia. Acta Trop. 2020;211:105596.

Akter R, Vythilingam I, Khaw LT, Qvist R, Lim YAL, Sitam FT, et al. Simian malaria in wild macaques: first report from Hulu Selangor district, Selangor, Malaysia. Malar J. 2015;14:386.

Peters W. Malaria of the orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) in Borneo. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1976;275:439–82.

Poirriez J, Dei-Cas E, Dujardin L, Landau I. The blood-stages of Plasmodium georgesi, P. gonderi and P. petersi: course of untreated infection in their natural hosts and additional morphological distinctive features. Parasitology. 1995;111:547–54.

Sutherland CJ. Persistent parasitism: the adaptive biology of malariae and ovale malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:808–19.

Oguike MC, Betson M, Burke M, Nolder D, Stothard JR, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri circulate simultaneously in African communities. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:677–83.

Landau I, Lepers JP, Rabetafika L, Baccam D, Peters W, Coulanges P. Plasmodia of lemurs in Madagascar. Ann Parasitol Hum Com. 1989;64:171–84.

Prugnolle F, Durand P, Neel C, Ollomo B, Ayala FJ, Arnathau C, et al. African great apes are natural hosts of multiple related malaria species, including Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1458–63.

Prugnolle F, Rougeron V, Becquart P, Berry A, Makanga B, Rahola N, et al. Diversity, host switching and evolution of Plasmodium vivax infecting african great apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8123–8.

Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, et al. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature. 2010;467:420–5.

Duval L, Nerrienet E, Rousset D, Sadeuh Mba SA, Houze S, Fourment M, et al. Chimpanzee malaria parasites related to Plasmodium ovale in Africa. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5520.

Coatney GR. The simian malarias: zoonoses, anthroponoses, or both? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1971;20:795–803.

Huyse T, Poulin R, Théron A. Speciation in parasites: a population genetics approach. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:469–75.

Wood CL, Johnson PTJ. How does space influence the relationship between host and parasite diversity? J Parasitol. 2016;102:485–94.

Johnson KP, Adams RJ, Page RDM, Clayton DH. When do parasites fail to speciate in response to host speciation? Syst Biol. 2003;52:37–47.

Poulin R, Mouillot D. Parasite specialization from a phylogenetic perspective: a new index of host specificity. Parasitology. 2003;126:473–80.

Araujo SBL, Braga MP, Brooks DR, Agosta SJ, Hoberg EP, Von Hartenthal FW, et al. Undestanding host-switching by ecological fitting. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139225.

Aleta A, De Arruda GF, Moreno Y, Jones M, O’Brien M, Mecum B, et al. Data-driven contact structures: from homogeneous mixing to multilayer networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020;16:e1008035.

Glenn TC, Pierson TW, Bayona-Vásquez NJ, Kieran TJ, Hoffberg SL, Thomas JC, et al. Adapterama II: Universal amplicon sequencing on Illumina platforms (TaggiMatrix). PeerJ. 2019;7:e7786.

Ngoubangoye B, Boundenga L, Arnathau C, Mombo IM, Durand P, Tsoumbou TA, et al. The host specificity of ape malaria parasites can be broken in confined environments. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46:737–44.

Phang WK, Hamid MHA, Jelip J, Mudin RN, Chuang TW, Lau YL, et al. Spatial and temporal analysis of Plasmodium knowlesi infection in peninsular Malaysia, 2011 to 2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9271.

Vythilingam I, Noorazian YM, Huat TC, Jiram AI, Yusri YM, Azahari AH, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi in humans, macaques and mosquitoes in peninsular Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:26.

Zhang X, Kadir KA, Quintanilla-Zariñan LF, Villano J, Houghton P, Du H, et al. Distribution and prevalence of malaria parasites among long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in regional populations across Southeast Asia. Malar J. 2016;15:450.

Proto WR, Siegel SV, Dankwa S, Liu W, Kemp A, Marsden S, et al. Adaptation of Plasmodium falciparum to humans involved the loss of an ape-specific erythrocyte invasion ligand. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4512.

Galaway F, Yu R, Constantinou A, Prugnolle F, Wright GJ. Resurrection of the ancestral RH5 invasion ligand provides a molecular explanation for the origin of P. falciparum malaria in humans. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000490.

Boundenga L, Ollomo B, Rougeron V, Mouele LY, Mve-Ondo B, Delicat-Loembet LM, et al. Diversity of malaria parasites in great apes in Gabon. Malar J. 2015;14:111.

Sundararaman SA, Liu W, Keele BF, Learn GH, Bittinger K, Mouacha F, et al. Plasmodium falciparum-like parasites infecting wild apes in southern Cameroon do not represent a recurrent source of human malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7020–5.

Rutledge GG, Böhme U, Sanders M, Reid AJ, Cotton JA, Maiga-Ascofare O, et al. Plasmodium malariae and P. ovale genomes provide insights into malaria parasite evolution. Nature. 2017;542:101–4.

Ewen JG, Bensch S, Blackburn TM, Bonneaud C, Brown R, Cassey P, et al. Establishment of exotic parasites: the origins and characteristics of an avian malaria community in an isolated island avifauna. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:1112–9.

Woolhouse MEJ, Taylor LH, Haydon DT. Population biology of multihost pathogens. Science. 2001;292:1109–12.

Duval L, Fourment M, Nerrienet E, Rousset D, Sadeuh SA, Goodman SM, et al. African apes as reservoirs of Plasmodium falciparum and the origin and diversification of the Laverania subgenus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10561–6.

Pacheco MA, Cranfield M, Cameron K, Escalante AA. Malarial parasite diversity in chimpanzees: The value of comparative approaches to ascertain the evolution of Plasmodium falciparum antigens. Malar J. 2013;12:328.

Kaiser M, Löwa A, Ulrich M, Ellerbrok H, Goffe AS, Blasse A, et al. Wild chimpanzees infected with 5 Plasmodium species. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1956–9.

Mapua MI, Fuehrer H, Petrželková KJ, Todd A, Noedl H, Qablan MA, et al. Plasmodium ovale wallikeri in Western Lowland gorillas and humans, Central African Republic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1581–3.

Waters AP, Higgins DG, McCutchan TF. Plasmodium falciparum appears to have arisen as a result of lateral transfer between avian and human hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3140–4.

Escalante AA, Ayala FJ. Phylogeny of the malarial genus Plasmodium, derived from rRNA gene sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11373–7.

Escalante AA, Ayala FJ. Evolutionary origin of Plasmodium and other Apicomplexa based on rRNA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5793–7.

Qari SH, Shi YP, Pieniazek NJ, Collins WE, Lal AA. Phylogenetic relationship among the malaria parasites based on small subunit rRNA gene sequences: monophyletic nature of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;6:157–65.

Nishimoto Y, Arisue N, Kawai S, Escalante AA, Horii T, Tanabe K, et al. Evolution and phylogeny of the heterogeneous cytosolic SSU rRNA genes in the genus Plasmodium. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;47:45–53.

Gunderson JH, Sogin ML, Wollett G, Hollingdale M, de la Cruz VF, Waters AP, et al. Structurally distinct, stage-specific ribosomes occur in Plasmodium. Science. 1987;238:933–7.

Escalante AA, Barrio E, Ayala FJ. Evolutionary origin of human and primate malarias: evidence from the circumsporozoite protein gene. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:616–26.

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:238.

Gilabert A, Otto TD, Rutledge GG, Franzon B, Ollomo B, Arnathau C, et al. Plasmodium vivax-like genome sequences shed new insights into Plasmodium vivax biology and evolution. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2006035.

Otto TD, Gilabert A, Crellen T, Böhme U, Arnathau C, Sanders M, et al. Genomes of all known members of a Plasmodium subgenus reveal paths to virulent human malaria. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:687–97.

Aunin E, Böhme U, Sanderson T, Simons ND, Goldberg TL, Ting N, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for descent from Plasmodium and loss of blood schizogony in Hepatocystis parasites from naturally infected red colobus monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008717.

Tachibana SI, Sullivan SA, Kawai S, Nakamura S, Kim HR, Goto N, et al. Plasmodium cynomolgi genome sequences provide insight into Plasmodium vivax and the monkey malaria clade. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1051–5.

Böhme U, Otto TD, Cotton JA, Steinbiss S, Sanders M, Oyola SO, et al. Complete avian malaria parasite genomes reveal features associated with lineage-specific evolution in birds and mammals. Genome Res. 2018;28:547–60.

Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S. ASTRAL-III: Polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinform. 2018;19 Suppl 6:153.

Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, Von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–4.

Pacheco MA, Poe AC, Collins WE, Lal AA, Tanabe K, Kariuki SK, et al. A comparative study of the genetic diversity of the 42kDa fragment of the merozoite surface protein 1 in Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:180–7.

Stentiford GD, Feist SW, Stone DM, Peeler EJ, Bass D. Policy, phylogeny, and the parasite. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:274–81.

Lee KS, Cox-Singh J, Singh B. Morphological features and differential counts of Plasmodium knowlesi parasites in naturally acquired human infections. Malar J. 2009;8:73.

Pacheco MA, Escalante AA. Cophylogenetic patterns and speciation in avian haemosporidians. In: Santiago-Alarcon D, Marzal A, editors. Avian malaria and related parasites in the tropics: ecology, evolution and systematics. Springer Nature: Switzerland AG; 2020. p. 401–27.

Valkiunas G, Ashford RW, Bensch S, Killick-Kendrick R, Perkins S. A cautionary note concerning Plasmodium in apes. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:231–2.

Lutz HL, Patterson BD, Kerbis Peterhans JC, Stanley WT, Webala PW, Gnoske TP, et al. Diverse sampling of East African haemosporidians reveals chiropteran origin of malaria parasites in primates and rodents. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;99:7–15.

Borner J, Pick C, Thiede J, Kolawole OM, Kingsley MT, Schulze J, et al. Phylogeny of haemosporidian blood parasites revealed by a multi-gene approach. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;94:221–31.

Hewitt R. Bird malaria. Am. J. Hyg. Monogr. Ser. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press; 1940.