Abstract

Background

In malaria-endemic areas, human populations are frequently exposed to immunomodulatory salivary components injected during mosquito blood feeding. The consequences on pathogen-specific immune responses are not well known. This study evaluated and compared the humoral responses specific to merozoite stage vaccine candidates of Plasmodium falciparum, in children differentially exposed to Anopheles bites in a natural setting.

Methods

The cross-sectional study was carried out in Bouaké (Côte d’Ivoire) where entomological data and blood samples from children (0–14 years) were collected in two sites with similar malaria prevalence. Antibody (IgG, IgG1, IgG3) responses to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 were evaluated by ELISA. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to assess the relationship between the immune responses to P. falciparum antigens and exposure to Anopheles bites in the total cohort and in each site, separately. The individual level of exposure to Anopheles bites was evaluated by quantifying specific IgG response to the Anopheles gSG6-P1 salivary peptide, which represents a proxy of Anopheles exposure.

Results

The anti-Plasmodium humoral responses were different according to the level of exposure of children, with those highly exposed to Anopheles presenting significantly lower antibody responses to PfMSP1 in total population (IgG and IgG3) and in Petessou village (IgG, IgG1, IgG3). No significant difference was seen for PfAMA1 antigen between children differently exposed to Anopheles. In Dar-es-Salam, a neighbourhood where a high Culex density was reported, children presented very low antibody levels specific to both antigens, and no difference according to the exposure to Anopheles bites was found.

Conclusion

These findings may suggest that immunomodulatory components of Anopheles saliva, in addition to other factors, may participate to the modulation of the humoral response specific to Plasmodium merozoite stage antigens. This epidemiological observation may form a starting point for additional work to decipher the role of mosquito saliva on the modulation of the anti-Plasmodium acquired immunity and clinical protection in combining both field and ex vivo immunological studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the progress achieved in controlling malaria, it remains a major health problem contributing to morbidity and mortality especially in children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa. Substantial reductions in the global burden of malaria were noted during the past two decades but progress has stagnated. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 219 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide, an increase of 2 million from the previous year [1]. Malaria elimination efforts are threatened by the emergence of the resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to anti-malarial drugs [2], by increasing and widespread mosquito vector resistance to insecticides [3], and by the lack of an effective vaccine conferring strong protective immunity to infection [4].

In malaria-endemic areas, human populations develop natural immunity against P. falciparum that can lead to premunition. This acquired protective immunity takes years to develop after repeated exposure to Plasmodium parasite, is relatively short-lived, and is partially effective. It can efficiently control malaria parasite infection leading to a decline in clinical malaria since low parasitaemia mostly persists in the presence of circulating antibodies (Abs). Protective immunity is largely mediated by specific Abs, including immunoglobulin G (IgG) and cytophilic sub-classes (IgG1 and IgG3) [5], that mostly target the P. falciparum blood-stage antigens (Ags), such as apical membrane antigen 1 (PfAMA1) [6], merozoite surface protein 1 and 3 (PfMSP1, PfMSP3) [7, 8], and glutamate-rich protein (PfGLURP) [9, 10].

Malaria vaccines currently under development aim to prime such protective responses, particularly in young children and infants. To date, varying formulations of PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 account for the majority of the vaccines that have reached the clinic [11], except the pre-erythrocytic vaccine RTS,S/AS01, based on circumsporozoite protein (CSP) from the sporozoite stage. RTS,S is the most promising malaria vaccine, reaching phase 3 in a clinical trial and approved for use by European regulators in 2015 (Mosquirix™). Modest but significant heterogeneity between individuals regarding the efficacy of infection-blocking vaccine was seen across sites, ranging from 40 to 77% [12].

Immune responses are complex traits and vaccine development requires extensive knowledge of the processes and of the determinants that modulate immune responses in human populations. The effect of age, genetic factors, pathogen co-infection, and nutritional status have been more intensively explored and are recognized to influence anti-Plasmodium Ab responses and to have some association with malaria clinical protection [13,14,15].

Environmental factors as chemical, biological and physical factors may also influence immunity activity [16] and vaccine responses [17]. Environmental exposure can drive epigenetic modification which allows for adaptative immune-T cell activation [18] and memory responses [19] as well as exposure to immuno-toxic or -modulatory activities that can altered immune functions. Interestingly, few studies showed that Ab responses to certain specific vaccines (pneumococcal, rabies, and typhoid vaccines) may be influenced by month of vaccine administration [20] suggesting that seasonally variable environmental Ags may have a co-stimulatory effect on immune responses. Changing temperature, diurnal exposure to sunlight, food availability, and exposure to infectious agents may be part of the different season environmental factors that may act on the immune system. In malaria-endemic areas, human populations are repeatedly exposed to salivary components of blood-feeding mosquitoes that possess a variety of pharmacologically active biomolecules with anti-haemostatic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties to counter the host defense responses activated during a blood meal [21]. There is now evidence that co-injected saliva has immunomodulatory properties, and studies support a role for mosquito saliva in enhancing pathogen transmission via the modulation of Th1/Th2 immune responses [22, 23].

Experimental studies across a wide range of arthropods and their associated pathogens indicated that, generally, insect saliva enhances infection by orientating the immune response of the vertebrate toward a Th2 profile, whereas prior repeated exposure to uninfected bites leads to the development of a Th1 response with a decrease in infection severity [24, 25]. A more recent study in humanized mice suggests that a mixture of Th1 and Th2 responses are upregulated by mosquito saliva and can last for several days in the skin and bone marrow [26]. Most of studies have been performed in murine models and it is obvious that the investigation of this question in human populations from endemic settings is much more complicated. Relatively few studies have investigated the effects of mosquito saliva on human cells ex vivo [27] and on cytokine production from human cells following stimulation with mosquito saliva [28,29,30]. Altogether, it suggests that human immune response to mosquito saliva is significant and complex: mosquito saliva alters the frequencies of several immune cell populations and cytokine production, in multiple tissues, at several times after blood feeding [26].

The immune microenvironment initiated by arthropod salivary components in the vertebrate host may have consequences for the development of specific immune response against pathogens. So far, few studies have investigated specifically this assumption. Two independent experimental studies suggested that mice exposed either to Anopheles or to tick feeding showed a down-regulated Ag-specific immune response compared to naïve mice (model Ag = ovalbumin and BSA, respectively) [31, 32]. Studies extending this approach from murine to natural infection in humans living in malaria-endemic settings are challenging but required. Previous studies showed that acquired anti-Plasmodium IgG responses in children differed in two geographic areas where the level of exposure to Anopheles vectors was markedly different [33]. Sarr et al. showed a modulation of the balance of cytophilic Ab responses to parasite Ags according to the level of exposure of children to Anopheles bites. High exposure to Anopheles bites seemed to down-regulate the protective IgG1 Ab responses to whole Plasmodium extracts and to CSP Ag, whereas specific IgG3 responses were similar for the two Plasmodium Ags in villages exposed to either low or high levels of Anopheles bites [34].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate and compare the immunological profiles of IgG, IgG1, and IgG3 responses specific to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 vaccine candidates, in children differentially exposed to Anopheles bites in a natural setting. Interestingly, the intensity of Anopheles exposure was assessed at an individual level by evaluating the IgG level specific to the Anopheles gambiae gSG6-P1 salivary peptide. For the last decade, new immune-epidemiological tools have been developed that aimed at evaluating the level of exposure to mosquito bites at population and individual level [35]. These innovative tools are based on the measure of human antibody responses to salivary proteins of arthropod vector injected during the bite. As far as the Anopheles genus is concerned, the IgG response to the gSG6-P1 peptide (An. gambiae Salivary Gland Protein-6 peptide 1) of An. gambiae saliva has been identified and validated as a pertinent biomarker of Anopheles bites [36,37,38]. It represents a proxy of human exposure to Anopheles bites and is a reliable tool for assessing spatial and temporal heterogeneity of exposure at the individual level [35]. The gSG6-P1 salivary peptide is specific to the Anopheles genus, antigenic, easy to synthesize and highly conserved between Anopheles mosquitoes.

Methods

Ethics statement

The present study followed the ethical principles according to the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health of Côte d’Ivoire (June 2014; No. 41/MSLS/CNER-dkn). Site leaders provided prior permission to survey on each site and informed consent was obtained from all parents or guardians of children.

Study sites and population

The study was conducted in Bouaké (7° 69 N, 5° 03 W) located in the centre of Côte d’Ivoire. The study area, study design, and local malaria epidemiology have been previously described in detail [39]. Briefly, the climate is tropical humid with two seasons: the dry season runs from November through March, and the rainy season occurs from April to October. The rainy season is marked by two maximum rainfalls, one in June and one in September, with an average annual rainfall of between 1000 and 1600 mm. In this area, malaria transmission is intense with P. falciparum the major parasite species [40] and An. gambiaesensu lato (s.l.). the major vector [41].

The initial cohort consisted of 212 children aged from 6 months to 14 years from two sites (a sub-set of a cohort of 508 children from 5 sites [39]) and enrolled in a cross-sectional study which was carried out during the rainy season (August 2014). Households and children were randomly selected and sociological, geographical, entomological, and clinical data were collected. Children’s axillary temperature was measured, and thick films and blood smears were performed for all participants to determine parasite density and Plasmodium species. Thick blood smears were fixed and stained with 10% Giemsa and read at double blind by certified microscopists. Asexual parasite densities were counted against 200 microscope fields white blood cells assuming 8000 white blood cells per microlitre. A blood smear was considered negative if no parasites were observed. For quality control, 10% of slides were re-read by blind expert reader.

The present study was carried out on a sub-sample of the initial cohort and consisted of 95 uninfected children aged from 6 months to 14 years from two sites, Dar-es-Salam (a neighbourhood of Bouaké city) and Petessou (a village near Bouaké). Only 76 children were included in the final analysis, after having defined the groups of exposure to Anopheles (see below).

For immunological assays, blood samples were collected at the fingertips in microtainer tubes (microvette 500 serum-Gel Starstedt, Marnay, France) and sera were obtained after centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Sera were fractionated into aliquots and then frozen at − 20 °C until used.

Mosquito collection

Adult mosquitoes were collected in June and September 2014, as described [39]. In each of the two sites, six catching points, three indoor and three outdoor were used to collect mosquitoes by landing catches on adult volunteers for two consecutive nights (from 18.00. to 06.00). Adult mosquito catchers gave prior informed consent and received yellow fever vaccination and anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis as recommended by the National Malaria Control Programme. Adult mosquitoes were collected, counted and their species were morphologically classified at the laboratory. The human biting rate (HBR) of each mosquito species was calculated as the average number of mosquitoes collected per person per night.

Measurement of human IgG antibody level for gSG6-P1 salivary antigen

Human IgG level against the gSG6-P1 salivary antigen of An. gambiae was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp micro-assay plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with gSG6-P1 salivary antigen (GPS 1216, Genepep, Saint Jean de Védas, France) at a concentration of 20 μg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using 100 µl/well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h 30. Plates were blocked for 1 h with 200 μL of protein-free blocking buffer, pH7.4 (Thermo scientific, Rockford, USA). The plates were then washed and sera were incubated in duplicate wells at 4 °C overnight at 1/320 dilution in PBS containing 1% of Tween 20 (1%-PBST). Mouse biotinylated Ab to human IgG (BD Pharmingen, San Diego CA, USA) was incubated at a 1/4000 dilution in 1%-PBST (1 h 30 at 37 °C) and Extravidine biotine peroxydase (Amersham, les Ulis, France) was then added (1/20,000; 1 h at 37 °C). Colorimetric development was carried out using ABTS (2.2′-azino-bis (3 ethylbenzthiazoline 6-sulfonic acid) diammonium; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in citrate buffer (Sigma, pH4, containing 0.003% H2O2) and the optical density (OD) was read 2 h later at 405 nm.

Individual results were expressed as the ΔOD value: ΔOD = ODx-ODn, where ODx represents the mean of individual optical density (OD) value in both wells with gSG6-P1 antigen and ODn the individual OD value for each serum without gSG6-P1 antigen.

Children were separated into 2 groups of exposure according to their IgG level to the gSG6-P1 peptide. The mean value of the total population (ΔODgSG6-P1 mean = 1.25) was determined as the threshold, and individuals (n = 17) presenting ΔODgSG6-P1 mean ± 0.1 (1.15 < ODgSG6-P1 < 1.35) have been withdrawn to clearly define 2 groups of individuals differently exposed to Anopheles. This results in a ‘low exposure group’ grouping individuals with ΔODgSG6-P1 < 1.15 and a ‘high exposure group’ with individuals with ΔODgSG6-P1 > 1.35, from either Petessou or Dar-es-Salam site.

Measurement of human IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 antibodies for PfAMA1 and PfMSP1

IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 level to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 (PfMSP1p19) recombinant proteins were measured by indirect ELISA as previously described [9]. Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp micro-assay plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 recombinant proteins at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml in coating buffer (PBS with red phenol 0.001%) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The plates were blocked with skimmed milk buffer (5% milk powder in PBS 0.1% Tween 20 (0.1%-PBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Individual sera were diluted in buffer (1% milk powder in 0.1%-PBST) and added in at a final dilution (1/750 for IgG, 1/200 IgG1 and 1/50 for IgG3) for PfMSP1 and (1/7500 for IgG, 1/3000 IgG1 and 1/100 for IgG3) for PfAMA1. Optimal dilutions were determined after several preliminary experiments. Plates were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 100 µl/well of HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Frederick, USA), IgG1 and IgG3 (Binding Site, Birmingham, UK) diluted respectively for PfMSP1 (1/7500; 1/2000 and 1/1000) and for PfAMA1 (1/5000; 1/2000 and 1/1000) in skimmed milk buffer (1% milk powder in 0.1%-PBST). TMB (Eco Tek, Kuldysen 10, Denmark) was used as a substrate and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2 M H2SO4 (100 µL/well). The OD was read after 30 min at 450 nm. Individual results (ΔOD) were expressed as above: ΔOD = ODx-ODn, where ODx represents the mean of individual OD value in both wells with P. falciparum antigen and ODn the individual OD value for each serum without antigen.

Data management and statistical analysis

Chi2 test was used to compare Plasmodium prevalence and HBR between the two studied sites. As antibody levels were not normally distributed, nonparametric tests were used for analyses. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparison of Ab levels between two independent groups. Linear regression was performed to compare Ab levels according to age of participants. Generalized linear model (GLM) was used to assess the relationship between the Ab titres specific to P. falciparum antigens and covariate factors (age, site and group of exposure). All statistical analysis was done using Prism version 5.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and R software (Version 3.3.3; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). All differences were considered as significant at p value< 0.05.

Results

Study population characteristics, parasitological and entomological data

Population demographic (gender ratio and mean age), parasitological (prevalence and geometric mean of P. falciparum density), and entomological data are presented for the initial and the study cohorts, according to the two study sites, in Table 1. In the initial cohort (n = 212), no significant difference was observed in P. falciparum prevalence (56.6 and 54%, respectively, χ2 = 0.057, df = 1, p = 0.811) and in parasite density in infected children (geometric mean (log 10) 3.5 parasites/µl and 4.6 parasites/µl, respectively, p = 0.079) between Petessou and Dar-es-Salam sites.

Table 1 presents the entomological data collected in each study site. The HBR of An. gambiae was significantly higher in Petessou than in Dar-es-Salam, with 78 bites per human per night (BHN) and 2 BHN reported, respectively. In Petessou, other Anopheles species were captured in much lower proportion: Anopheles pharoensis (1.8 BHN), Anopheles funestus (0.3 BHN) and Anopheles welcomei (0.17 BHN). The HBR of other major nocturnal mosquitoes (Culex spp.) was much higher in Dar-es-Salam than in Petessou, with 81 BHN reported in Dar-es-Salam whereas almost no Culex was collected in Petessou.

In this study, only the non-infected children residing in the two sites (n = 43 from Dar-es-Salam and n = 52 from Petessou) were selected. The gender ratio (p = 0.98) and mean age (p = 0.35) of the sub-set of children were not significantly different between the two study sites (Table 1).

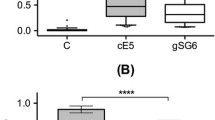

The specific IgG level to the gSG6-P1 salivary peptide representing a proxy of the intensity of exposure to Anopheles bites was also assessed in uninfected children residing in both sites. Children presented a wide range in ∆ODgSG6-P1 from 0 to 2.57 (Fig. 1). The median level of IgG response to the gSG6-P1 peptide was similar in children from Dar-es-Salam and Petessou (p = 0.129). Children were then separated into low or high exposure group according to their individual ∆ODgSG6-P1 value. Children from the low exposure group (∆ODgSG6-P1 < 1.15) had a similar IgG median level in Dar-es-Salam and in Petessou sites (p = 0.071), which indicated a similar level of exposure to Anopheles bites for the children from the low exposure group from each site. On the contrary, children from the high exposure group (∆ODgSG6-P1 > 1.35) from Dar-es-Salam had a significantly higher IgG median value than children from Petessou (p = 0.001), indicating that children from the high exposure group from Dar-es-Salam were higher exposed to Anopheles than did children from Petessou.

IgG response to An. gambiae gSG6-P1 salivary peptide in all uninfected children. Dot plots show the individual specific IgG level to gSG6-P1. Bar indicates the mean value, the grey dot line indicates the cut-off value of seropositivity and the blue dot lines represent the ΔODgSG6-P1 mean ± 0.1 that allow to define the two groups of exposure to Anopheles bites. Individuals with ΔODgSG6-P1 < 1.15 were considered as low exposed and individuals with ΔODgSG6-P1 > 1.35 were considered as high exposed to Anopheles bites

Univariate analysis of specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 levels and potential covariate factors

Total IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 responses of the participants to two merozoite (PfAMA1 and PfMSP1) P. falciparum stage antigens were evaluated. Univariate analysis was used to investigate the relation between specific anti-Plasmodium Ab responses and demographic factors (age, gender) and environmental factors (village and level of exposure to Anopheles bites) in the total cohort and in each study site, separately. The results presented in Table 2 showed that the level of the different Ab responses was not significantly (p > 0.05) influenced by age or gender.

The comparison of the Ab responses between groups of exposure indicated that a higher exposure to Anopheles mosquitoes was associated with a lower Ab levels to PfMSP1 antigen in the total population and in Petessou, but not in Dar-es-Salam. Indeed, children from the high exposure group had significantly lower IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 responses specific to PfMSP1 compared to children from the low exposure group in total population (p = 0.016, p = 0.034 and p = 0.04, respectively) and in Petessou (p = 0.001, p = 0.002 and p = 0.03, respectively). In contrast, difference in Anopheles exposure was not associated with a statistically significant effect on the levels of Ab responses to PfAMA1 antigen in the total population as well as in each site.

The comparison of Ab responses between site showed children from Dar-es-Salam presented significant lower Ab levels to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 P. falciparum Ags compared to children from Petessou (all p < 0.0001). In Dar-es-Salam, the median values of Ab responses specific to both Ags were very low.

Multivariate analysis of specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 responses in total population and in each study site

A multivariate analysis was used to further assess the relationship between the immune responses to P. falciparum merozoite stage antigens and exposure to mosquito bites. Age, level of exposure (group of exposure) and site were used as predictor variables (Table 3). In a general pattern, children from Dar-es-Salam presented significantly lower Ab responses to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 than children from Petessou (all p < 0.01) and no association was found between Ab responses to P. falciparum antigens and age. In the total population, a negative association was observed between the level of exposure and the anti-PfMSP1 Ab titres. Indeed children from the high exposure group presented a significant lower anti-PfMSP1 IgG (− 0.443, p = 0.043) and IgG3 (− 0.422, p = 0.033) titres whereas no association was found between Ab responses to PfAMA1 and groups of exposure. The same trend was observed only for children from Petessou, when the analysis was restricted to site. A higher exposure to Anopheles mosquitoes was associated with a trend toward decreased of the IgG (− 1.02, p = 0.003), IgG1 (− 1.09, p = 0.006) and IgG3 (− 0.653, p = 0.047) responses to PfMSP1 antigen only.

Discussion

Evidence now suggested that arthropod vectors on top of transmitting pathogens may also have roles in facilitating transmission and influencing disease evolution [25]; for instance the immuno modulatory properties of the co-injected saliva acts both on innate and adaptative immune responses of the vertebrate host [42]. Host immune responses to arthropod saliva are varied and complex, and depend both on the host and vector species [43]. The present study aimed to investigate the relationships between specific Ab responses to merozoite stage antigens (PfMSP1 and PfAMA1) in children differently exposed to Anopheles bites in two study sites in Côte d’Ivoire. Results showed that children higher exposed to Anopheles bites presented lower IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 responses to PfMSP1 in Petessou. No association between the level of exposure and Ab responses to PfAMA1 antigen was observed.

Exposure to Anopheles bites was investigated via two complementary methods: at the site scale with entomological indicators (human landing catches (HLC)) and at the individual level by using a serological biomarker of exposure based on the quantification of the IgG response specific to the An. gambiae gSG6-P1 salivary peptide. The two approaches did not give the same level of information about the exposure to Anopheles bites. HLC method indicates the mean number of bites that an individual may receive per night. Thus, it appreciates as an approximate proxy the level of exposure for each Culicidae species at site scale but does not take into account the inter-individual heterogeneity of exposure in natural setting. Indeed, environmental factors generating hot-spots of exposure (proximity to breeding sites for example), attraction an individual exerts on mosquitoes and the use of personal protection against mosquito bites (such as nets and coils) suggest that exposure to Anopheles bites can be highly variable from house to house and also between people living in the same house. Only the serological approach reflects the human–Anopheles contact and integrates the individual risk factors of being bitten. It provides for each participant a proxy of the individual level of exposure to Anopheles bites and thus, is more appropriate for reflecting the inter-individual heterogeneity of exposure in natural setting. Numerous studies have evidenced the Anopheles gSG6-P1 salivary peptide represents a reliable and complementary tool to entomological methods for assessing spatial and temporal heterogeneity of exposure to Anopheles bites at the individual level [35].

On the basis of comparison of HBR, children from Petessou had significantly higher exposure to Anopheles bites than did children from Dar-es-Salam, whereas the comparison of anti-gSG6-P1 IgG level (ΔODgSG6-P1 median and range) suggested that exposure to Anopheles bites was similar between the two sites. In Dar-es-Salam, the low number of Anopheles female caught during the entomological surveys may be explained by a low availability of breeding sites for Anopheles in urban setting. Anopheles classically like small, open, sunlit, fresh stagnant water suggesting a mosaic of isolated pockets of Anopheles breeding sites in the urban context that may result of local hot spots of Anopheles exposure that could not have been identified. As mentioned above, the use of vector control strategies and/or sociological factors specific to the urban context may also explain the discrepancies observed between the two approaches [39]. Parasitological data indicated that Plasmodium prevalence and density (the gold standard to measure the transmission of malaria) were similar between the two sites, thereby suggesting that children were exposed similarly to malaria transmission.

According to their individual anti-gSG6-P1 IgG level, children were separated into two exposure groups: low and high group of exposure to Anopheles bites. In the present study, when applying the cut-off of positivity (ΔODgSG6-P1 = 0.204) [44, 45], one individual from Petessou and two from Dar-es-Salam were seronegative indicating that all but three individuals can be considered exposed to Anopheles. In addition, the wide range of ΔODgSG6-P1 values in either Petessou and Dar-es-Salam, suggested that participants with higher ΔODgSG6-P1 values were bitten more in comparison to those with lower ΔODgSG6-P1 values and thereby applying a threshold (mean ΔODgSG6-P1 ± 0.1) would stratified the population in two groups with different level of exposure to Anopheles bites.

IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 levels to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 merozoite stage antigens were compared according to demographic factors and between groups of exposure. No statistically significant effect of age (univariate and multivariate analysis) or gender (univariate analysis) on the level of Abs specific to PfAMA1 and PfMSP1 was noted. According to univariate and multivariate analysis, specific Ab titres to PfMSP1 differed significantly between groups of exposure in total population (IgG and IgG3) and in Petessou village (IgG, IgG1 and IgG3). A higher exposure to Anopheles bites was associated with a significant trend toward lower IgG, IgG1 and IgG3 responses specific to PfMSP1. A higher Ab titres could be expected in children higher exposed to Anopheles bites and, therefore, to malaria transmission. Nevertheless, the epidemiological observation in the present study is consistent with studies that reported a down-regulated immune response to specific Ag in mice exposed to arthropod saliva compared to naïve mice [31, 32]. Exposure to biting mosquitoes may lead to a modification of the host’s immune cells and of the balance between Th1 and Th2 cytokine production [26]. Several experimental murine studies showed that Th2 cytokines as IL-4, the inhibitory cytokine IL-10 and the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF, were up-regulated after uninfected Aedes, Culex or Anopheles mosquito bites [31, 46, 47]. The secretion of the immunosuppressive IL-10 cytokine could increase the proliferation of T regulatory cells and down-regulate specific Ab immune response because it inhibits Ag presentation, IFN-γ expression, and macrophage activation. IL-10 has also been involved in the balance of cytophilic Ab responses [48]. Thus, it is conceivable that the potential decrease of Ab levels in children higher exposed may be associated with a lower IL-10 production. This hypothesis could be assessed by analysing the ex vivo cytokine production of immune cells from individuals differently exposed to Anopheles bites.

Only a few epidemiological studies have previously reported an association between exposure to Anopheles immunomodulatory saliva and acquisition of natural immunity to Plasmodium in natural settings. Sarr et al. reported that children with higher exposure to Anopheles bites presented a down-regulated IgG1 response to whole Plasmodium extract and to CSP Ag compared to children lower exposed, whereas no effect was observed for the IgG3 isotype response [34]. Dechavanne et al. reported that an environmental variable (quantitative index related to the spatiotemporal risk of exposure to Anopheles mosquitoes) was significantly associated with high anti-Plasmodium Ab levels in infants (6–18 month old infants) [13]. A recent study in malaria elimination context also showed a positive association between Anopheles exposure and IgG responses to PfCSP and PfMSP1 Ags [49]. Differences observed between studies might be attributed to the different context of exposure to Anopheles bites. Indeed, the history and intensity of exposure to mosquito bites may have different effect on immune system, as mentioned in experimental studies that reported a immunostimulatory effect with low concentrations of saliva whereas high concentrations were immunosuppressive [50]. Human studies in different malaria context are therefore needed even if challenging, due to numerous co-factors from the parasite, the human-host or environment that may modulate human immune system. The present study was carried out in uninfected children in order to minimize the antigenic boost of recent infection, thus the time since previous P. falciparum infection and rates of antibody decay may also participate in the differences observed between individuals from different groups of exposure. This represents a limit to the present study in addition to the small sample size. Malaria prevalence was near 50% in Petessou, thus it could be expected that individuals were regularly infected by Plasmodium parasites and that their last infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was recent. Other factors such as genetic background, co-infections, or nutritional status may also explain some of the differences in the immunological profiles observed between the two exposure groups.

No association between groups of exposure to Anopheles bites and humoral responses (IgG, IgG1 and IgG3) to PfAMA1 merozoite stage Ag was showed. This difference of effect according to Plasmodium Ags may be due to different intrinsic characteristics to merozoite Ags.

Children from Dar-es-Salam presented low level of anti-Plasmodium Abs. Parasitological data indicated that both sites had a similar intensity of malaria transmission with around 50% of malaria prevalence in the initial population. This suggests that factors other than parasite exposure alone may modulate anti-Plasmodium humoral responses. For example, the effect of human genetic factors cannot be excluded since the study children did not belong to the same ethnic group [51, 52]. The population from Dar-es-Salam is mostly composed of Dioula and Manding, whereas autochthonous Baoulé live in the rural village of Petessou. Mosquito saliva is known to contain close to 100 secretory proteins, and comparative analyses indicated that Culex and Aedes saliva have specific salivary proteins not found in Anopheles saliva [53, 54]. The exposure to other mosquito salivary components with immunomodulatory properties may also participate in the modulation of the anti-Plasmodium immune responses. The presence of anthropophilic Culex species was reported only in Dar-es-Salam site by entomological data. Exposure to immunomodulatory components of Culex saliva may also contribute, in addition to other factors, to the down-regulation of the immune responses observed in children from Dar-es-Salam. The availability of a serological biomarker of exposure assessing specifically the exposure to Culex spp. bites at the individual level would be valuable in multivariate analysis to strengthen the hypothesis.

Further studies are needed in order to better characterize the effects of mosquito saliva on human immune system, for example by analysing ex vivo cytokine production after stimulation of peripheral blood of mononuclear cells from individuals differentially exposed to mosquito bites. More evidence on its immunomodulatory effects on naturally acquired immunity to Plasmodium has to be provided with field studies in different epidemiological context.

Immune responses are complex traits and little is known about the environmental factors modulating acquired immunity to Plasmodium and premunition despite its essential role in the clinical outcome of malaria infections and in the development of vaccine immunity. Salivary modulators of the immune system could be prime targets for the development of transmission-blocking vaccines. Indeed, taking advantage of the modulation induced by saliva (e.g., neutralization of the immune suppression) would help the host’s immune system to respond to pathogens. Interestingly, over the past few years, combining pathogen and salivary Ags in a single vaccine is seen as a valuable option [55]. Elucidating the mechanism may also lead to the discovery of new immunosuppressive molecules of therapeutic interest. These findings may also have an important impact on the evaluation of vaccine efficacy. Inter-individual variability in humoral immune responses to a specific P. falciparum antigen has been reported in different studies evaluating the immunogenicity of vaccine candidates [56, 57]. The exposure to immunomodulatory insect salivary proteins during or after the immunization period could modulate the acquisition as well the durability of Ab responses to vaccine Ag, as noted for rabies or typhoid vaccines [20]. It could also have consequences on the immunological profiles induced in terms of intensity and/or isotype distribution, and thus on the efficacy of the protective immunity. In this framework, it is clear that a better understanding of the modulation of protective and anti-vaccine immune responses by epidemiological and environmental factors is of public health relevance and would be valuable for malaria vaccine development.

Conclusion

The main results of the present study show children differently exposed to Anopheles bites presented different levels of Ab responses to PfMSP1 antigen. These findings may suggest that immunomodulatory components of Anopheles saliva, in addition to other factors, may participate to the modulation of the humoral response specific to Plasmodium merozoite stage antigens. This epidemiological observation may form a starting point for additional works to better evidence and characterize the effects of mosquito saliva on the human immune system and on the anti-Plasmodium acquired immunity in combining both field and ex vivo immunological studies.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the last author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- gSG6-P1:

-

An. gambiae Salivary Gland Protein-6 peptide 1

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ΔOD:

-

Delta optical density

- PfAMA1:

-

Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1

- PfMSP1:

-

Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1

- HBR:

-

Human biting rate

- BHN:

-

Bites per human per night

References

WHO. World malaria report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Lu F, Culleton R, Cao J. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:306.

Ranson H, Lissenden N. Insecticide resistance in African Anopheles mosquitoes: a worsening situation that needs urgent action to maintain malaria control. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:187–96.

Crompton PD, Pierce SK, Miller LH. Advances and challenges in malaria vaccine development. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4168–78.

Marsh K, Kinyanjui S. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:51–60.

Nebie I, Diarra A, Ouedraogo A, Soulama I, Bougouma EC, Tiono AB, et al. Humoral responses to Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage antigens and association with incidence of clinical malaria in children living in an area of seasonal malaria transmission in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Infect Immun. 2008;76:759–66.

Wang Q, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Li X, Zhu M, Li P, et al. Naturally acquired antibody responses to Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1) C-terminal 19 kDa domains in an area of unstable malaria transmission in southeast Asia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151900.

Kana IH, Garcia-Senosiain A, Singh SK, Tiendrebeogo RW, Chourasia BK, Malhotra P, et al. Cytophilic antibodies against key Plasmodium falciparum blood stage antigens contribute to protection against clinical malaria in a high transmission region of eastern India. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:956–65.

Courtin D, Oesterholt M, Huismans H, Kusi K, Milet J, Badaut C, et al. The quantity and quality of African children’s IgG responses to merozoite surface antigens reflect protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7590.

Dodoo D, Theisen M, Kurtzhals JA, Akanmori BD, Koram KA, Jepsen S, et al. Naturally acquired antibodies to the glutamate-rich protein are associated with protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1202–5.

Miura K. Progress and prospects for blood-stage malaria vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15:765–81.

The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership. Efficacy and safety of the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine during 18 months after vaccination: a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in children and young infants at 11 african sites. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001685.

Dechavanne C, Sadissou I, Bouraima A, Ahouangninou C, Amoussa R, Milet J, et al. Acquisition of natural humoral immunity to P. falciparum in early life in Benin: impact of clinical, environmental and host factors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33961.

Goncalves RM, Lima NF, Ferreira MU. Parasite virulence, co-infections and cytokine balance in malaria. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:173–8.

Fillol F, Sarr JB, Boulanger D, Cisse B, Sokhna C, Riveau G, et al. Impact of child malnutrition on the specific anti-Plasmodium falciparum antibody response. Malar J. 2009;8:116.

MacGillivray DM, Kollmann TR. The role of environmental factors in modulating immune responses in early life. Front Immunol. 2014;5:434.

Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00084.

Bruniquel D, Schwartz RH. Selective, stable demethylation of the interleukin-2 gene enhances transcription by an active process. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:235–40.

Northrop JK, Thomas RM, Wells AD, Shen H. Epigenetic remodeling of the IL-2 and IFN-gamma loci in memory CD8 T cells is influenced by CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:1062–9.

Moore SE, Collinson AC, Fulford AJ, Jalil F, Siegrist CA, Goldblatt D, et al. Effect of month of vaccine administration on antibody responses in The Gambia and Pakistan. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1529–41.

Ribeiro JM. Role of saliva in blood-feeding by arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 1987;32:463–78.

Schneider BS, Mathieu C, Peronet R, Mécheri S. Anopheles stephensi saliva enhances progression of cerebral malaria in a murine model. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:423–32.

Styer LM, Lim P-Y, Louie KL, Albright RG, Kramer LD, Bernard KA. Mosquito saliva causes enhancement of West Nile virus infection in mice. J Virol. 2011;85:1517–27.

Schneider BS, Soong L, Zeidner NS, Higgs S. Aedes aegypti salivary gland extracts modulate anti-viral and TH1/TH2 cytokine responses to Sindbis virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2004;17:565–73.

Schneider BS, Higgs S. The enhancement of arbovirus transmission and disease by mosquito saliva is associated with modulation of the host immune response. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:400–8.

Vogt MB, Lahon A, Arya RP, Kneubehl AR, Spencer Clinton JL, Paust S, et al. Mosquito saliva alone has profound effects on the human immune system. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006439.

Liu S, Kelvin DJ, Leon AJ, Jin L, Farooqui A. Induction of Fas mediated caspase-8 independent apoptosis in immune cells by Armigeres subalbatus saliva. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41145.

Rogers KA, Titus RG. Immunomodulatory effects of Maxadilan and Phlebotomus papatasi sand fly salivary gland lysates on human primary in vitro immune responses. Parasite Immunol. 2003;25:127–34.

Koga C, Sugita K, Kabashima K, Matsuoka H, Nakamura M, Tokura Y. High responses of peripheral lymphocytes to mosquito salivary gland extracts in patients with Wells syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:160–1.

Tokura Y, Matsuoka H, Koga C, Asada H, Seo N, Ishihara S, et al. Enhanced T-cell response to mosquito extracts by NK cells in hypersensitivity to mosquito bites associated with EBV infection and NK cell lymphocytosis. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:519–26.

Depinay N, Hacini F, Beghdadi W, Peronet R, Mécheri S. Mast cell-dependent down-regulation of antigen-specific immune responses by mosquito bites. J Immunol. 2006;176:4141–6.

Menten-Dedoyart C, Couvreur B, Thellin O, Drion PV, Herry M, Jolois O, et al. Influence of the Ixodes ricinus tick blood-feeding on the antigen-specific antibody response in vivo. Vaccine. 2008;26:6956–64.

Sarr JB, Remoue F, Samb B, Dia I, Guindo S, Sow C, et al. Evaluation of antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum in children according to exposure of Anopheles gambiae s.l. or Anopheles funestus vectors. Malar J. 2007;6:117.

Sarr JB, Samb B, Sagna AB, Fortin S, Doucoure S, Sow C, et al. Differential acquisition of human antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum according to intensity of exposure to Anopheles bites. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:460–7.

Sagna A, Poinsignon A, Remoue F. Epidemiological applications of assessing mosquito exposure in a malaria-endemic area. In: Sagna A, editor. Arthropod vector: controller of disease transmission, vol. 2. New York: Elsevier; 2017. p. 209–29.

Poinsignon A, Cornelie S, Mestres-Simon M, Lanfrancotti A, Rossignol M, Boulanger D, et al. Novel peptide marker corresponding to salivary protein gSG6 potentially identifies exposure to Anopheles bites. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2472.

Traoré DF, Sagna AB, Adja AM, Zoh DD, Adou KA, Lingué KN, et al. Exploring the heterogeneity of human exposure to malaria vectors in an urban setting, Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire, using an immuno-epidemiological biomarker. Malar J. 2019;18:68.

Ya-Umphan P, Cerqueira D, Parker DM, Cottrell G, Poinsignon A, Remoue F, et al. Use of an Anopheles salivary biomarker to assess malaria transmission risk along the Thailand-Myanmar border. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:396–404.

Traoré DF, Sagna AB, Adja AM, Zoh DD, Lingué KN, Coulibaly I, et al. Evaluation of malaria urban risk using an immuno-epidemiological biomarker of human exposure to Anopheles bites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1353–9.

Toure OA, Landry TNG, Assi SB, Kone AA, Gbessi EA, Ako BA, et al. Malaria parasite clearance from patients following artemisinin-based combination therapy in Côte d’Ivoire. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:2031–8.

Koffi AA, Ahoua Alou LP, Adja MA, Chandre F, Pennetier C. Insecticide resistance status of Anopheles gambiae s.s. population from M’Bé: a WHOPES-labelled experimental hut station, 10 years after the political crisis in Côte d’Ivoire. Malar J. 2013;12:151.

Fontaine A, Diouf I, Bakkali N, Misse D, Pages F, Fusai T, et al. Implication of haematophagous arthropod salivary proteins in host-vector interactions. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:187.

Wanasen N, Nussenzveig RH, Champagne DE, Soong L, Higgs S. Differential modulation of murine host immune response by salivary gland extracts from the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:191–9.

Drame PM, Machault V, Diallo A, Cornélie S, Poinsignon A, Lalou R, et al. IgG responses to the gSG6-P1 salivary peptide for evaluating human exposure to Anopheles bites in urban areas of Dakar region, Sénégal. Malar J. 2012;11:72.

Drame PM, Poinsignon A, Besnard P, Cornelie S, Le Mire J, Toto JC, et al. Human antibody responses to the Anopheles salivary gSG6-P1 peptide: a novel tool for evaluating the efficacy of ITNs in malaria vector control. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15596.

Cox J, Mota J, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Diamond MS, Rico-Hesse R. Mosquito bite delivery of dengue virus enhances immunogenicity and pathogenesis in humanized mice. J Virol. 2012;86:7637–49.

Zeidner NS, Higgs S, Happ CM, Beaty BJ, Miller BR. Mosquito feeding modulates Th1 and Th2 cytokines in flavivirus susceptible mice: an effect mimicked by injection of sialokinins, but not demonstrated in flavivirus resistant mice. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21:35–44.

Norsworthy NB, Sun J, Elnaiem D, Lanzaro G, Soong L. Sand fly saliva enhances Leishmania amazonensis infection by modulating interleukin-10 production. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1240–7.

Ya-Umphan P, Cerqueira D, Cottrell G, Parker DM, Fowkes FJI, Nosten F, et al. Anopheles salivary biomarker as a proxy for estimating Plasmodium falciparum malaria exposure on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:350–6.

Mejri N, Rutti B, Brossard M. Immunosuppressive effects of Ixodes ricinus tick saliva or salivary gland extracts on innate and acquired immune response of BALB/c mice. Parasitol Res. 2002;88:192–7.

Arama C, Maiga B, Dolo A, Kouriba B, Traoré B, Crompton PD, et al. Ethnic differences in susceptibility to malaria: what have we learned from immuno-epidemiological studies in West Africa? Acta Trop. 2015;146:152–6.

Farouk SE, Dolo A, Bereczky S, Kouriba B, Maiga B, Färnert A, et al. Different antibody- and cytokine-mediated responses to Plasmodium falciparum parasite in two sympatric ethnic tribes living in Mali. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:110–7.

Ribeiro JMC, Charlab R, Pham VM, Garfield M, Valenzuela JG. An insight into the salivary transcriptome and proteome of the adult female mosquito Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:543–63.

Calvo E, Sanchez-Vargas I, Favreau AJ, Barbian KD, Pham VM, Olson KE, et al. An insight into the sialotranscriptome of the West Nile mosquito vector, Culex tarsalis. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:51.

Zahedifard F, Gholami E, Taheri T, Taslimi Y, Doustdari F, Seyed N, et al. Enhanced protective efficacy of nonpathogenic recombinant Leishmania tarentolae expressing cysteine proteinases combined with a sand fly salivary antigen. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2751.

Mamo H, Esen M, Ajua A, Theisen M, Mordmuller B, Petros B. Humoral immune response to Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidate GMZ2 and its components in populations naturally exposed to seasonal malaria in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013;12:51.

Perraut R, Guillotte M, Drame I, Diouf B, Molez J-F, Tall A, et al. Evaluation of anti-Plasmodium falciparum antibodies in Senegalese adults using different types of crude extracts from various strains of parasite. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:31–5.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the populations of Bouaké’s health neighbourhood (Dar-es-Salam and Petessou) sites, especially householders and guardians of children for their kind support and collaboration. We kindly thank S. Longagre (Vaximax, France) for providing the PfMSP1p19 recombinant protein and E.J. Remarque (Biomedical Primate Research Centre, Rijswijk, The Netherlands) for the PfAMA1 recombinant protein. We would also like to especially thank Isabella Athanassiou (Bonn, Germany) for language editing.

Funding

This research was integrated into the EVAPALCI multidisciplinary study funded by the IRD (Jeune Equipe Associée à l’IRD, French National Institute for Research for Sustainable Development; Département des Programmes de Recherche et de la Formation au Sud; convention of February 18, 2013). K.G. Aka and A. B. Sagna were supported by a PhD and a postdoctoral fellowships provided by Méditerannée Infection Foundation, respectively. D.F. Traoré and D.D. Zoh were supported by fellowships from the IRD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP, FR, AMA, and SBA conceived the study. KGA, DFT, ABS, DDZ, and BNT collected data in field surveys; KGA, DFT, and ABS carried out the immunological assessments; and KGA analysed the data. KGA drafted the first manuscript. AP participated in preparing and writing the manuscript and revised the manuscript. AP, FR, ABS, and AMA provided guidance on revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study followed the ethical principles recommended by the Edinburgh revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Côte d’Ivoire Ministry of Health (June 2014; No. 41/MSLS/CNER-dkn). Written informed consent of all parents or guardians of children who participated in the study was obtained before inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aka, K.G., Traoré, D.F., Sagna, A.B. et al. Pattern of antibody responses to Plasmodium falciparum antigens in individuals differentially exposed to Anopheles bites. Malar J 19, 83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03160-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03160-5