Abstract

Background

Low mefloquine exposure has been shown to contribute to treatment failure in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria following a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine combination. The present study aimed to develop a population pharmacokinetic model for mefloquine based on whole blood concentration–time profiles of this target population for further dose optimization.

Methods

A total of 129 Burmese patients aged above 15 years who presented with typical symptoms of malaria and had a blood smear positive for Plasmodium falciparum were included in the study. All were treated with the standard 3-day combination regimen of artesunate and mefloquine consisting of mefloquine for 2 days and artesunate for 3 days. Blood samples were collected before and at different time points after drug administration from different sub-groups of patients. Mefloquine concentrations were quantified in whole blood using high-performance liquid chromatography. A non-linear mixed-effect modelling approach was applied for population pharmacokinetic analysis using the NONMEM v7.3 software. Covariates investigated (body weight, gender, admission parasitaemia, and molecular markers of mefloquine resistance) were investigated in a step-wise manner using the SCM functionality in Perl-Speaks-NONMEM.

Results

Population pharmacokinetic analysis of mefloquine was performed in all patients with a total of 653 samples. Whole blood mefloquine concentration–time profiles were described by a two-compartment disposition model. Of the covariates investigated, none was found to have a significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. Significant differences in maximum concentration (Cmax) and elimination half-life (t1/2) were found in patients who had treatment failure (36 cases) compared to patients with successful treatment (107 cases).

Conclusion

The study successfully describes the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine following a 2-day treatment of mefloquine as a part of a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria from Thailand. A model has been developed which adequately describes the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. More extensive clinical studies including both adults and children are needed to fully characterize the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria remains a significant infectious disease that kills over 1200 people every day [1]. The latest malaria report from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that the number of malaria cases in 2017, which has previously been in steady decline since 2010, has now increased compared to the year before (with an estimated 216 million cases in 2016 compared to 211 million in 2015) [1, 2]. One of the main reasons for this resurgence is the development and spread of multi-drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum [1]. To deal with the threat of resistance of P. falciparum to monotherapy, artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) was recommended by WHO in 2006 as a strategy to counteract the increasing resistance of P. falciparum to anti-malarials, as well as to prevent disease transmission and reduce the risk of drug resistance [3]. ACT consists of an artemisinin drug with a potent schizonticidal activity, together with a long elimination half-life partner drug, which is present in the blood at therapeutic concentrations for at least several of the parasite life cycles to prevent recrudescence [4]. These combinations have been shown to result in well-tolerated anti-malarial treatment, which acts rapidly and has a reliable and sustained efficacy. Their increasing use has been a critical factor behind the reduction in malaria transmission in Asia and other endemic areas of the world [4]. Unfortunately, artemisinin resistance has emerged during the last decade and has unfortunately spread within southeast Asia [5].

Among the recommended ACT regimens for falciparum malaria, artesunate–mefloquine combination was introduced as first-line treatment of multi-drug-resistant, uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand before WHO recommendation. The combination n was initially used in 1995 as a 2-day combination regimen of 25 mg/kg body weight of mefloquine and 12 mg/kg body weight of artesunate to ensure better compliance [6]. The recommendation changed to a 3-day treatment in 2007 to follow WHO recommendation. Recently, the combination has been replaced by dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine due to the low clinical efficacy of artesunate–mefloquine combination [7]. The resistance of P. falciparum to ACT is of great concern to global malaria control programmes as alternative treatment options are limited.

Introduction of the triple combination of anti-malarials instead of the standard two-drug combination has been suggested as a further strategy to control artemisinin resistance [8]. Artesunate–mefloquine combination could be part of these triple combination or could replace dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine in areas with piperaquine resistance is prevalent. In some countries, such as Vietnam, mefloquine has been added to the current dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine as first-line treatment. Altogether, this information highlights the necessity and importance of gaining more knowledge of the pharmacokinetics of the partner drug mefloquine in target populations at risks. It is therefore important to adequately describe the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in specific populations for appropriate dose optimization. In addition, the developed pharmacokinetic models can be further applied to predict optimal dose regimens in specific populations. The present study aimed to develop a population pharmacokinetic model for mefloquine based on data from adults with uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand.

Methods

Patients and treatment

This population pharmacokinetic study was a part of the study protocol to investigate the clinical efficacy of a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine combination in patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria in an endemic area along the Thai–Myanmar border. The study was conducted at Mae Tao clinic for migrant workers, Tak Province, Thailand, from March 2008 to February 2009. Ethical approval of the study protocol was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand. Detailed information of the study procedures and results of clinical efficacy assessment, including the relationship with drug concentrations were previously described in detail [9].

Burmese patients, aged over 15 years, who had typical symptoms of malaria and were positive for P. falciparum diagnosed with blood smears, were included in the study. Inclusion criteria for enrolment in the study were patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria according to the WHO protocol for areas with low to moderate malaria transmission [10]; patients with signs of severe or complicated malaria [11]; history of hypersensitivity reactions to any of the study drug; the presence of severe malnutrition; febrile diseases other than malaria. Pregnant or breast-feeding women were not included. All patients provided written informed consents before study participation.

All patients received a 3-day combination regimen of artesunate and mefloquine. An initial dose consisting of 4 mg/kg body weight of artesunate (200 mg, 4 tablets of 50 mg artesunate, Atlantic Pharmaceutical Company, Thailand) and 15 mg/kg body weight of mefloquine (750 mg, 3 tablets of 250 mg mefloquine; Atlantic Pharmaceutical Company, Thailand) was given on the first day of the study. On the second day, the patients received 4 mg/kg body weight of artesunate (200 mg, 4 tablets of 50 mg artesunate) and 10 mg/kg body weight of mefloquine (500 mg, 2 tablets of 250 mg mefloquine). On the third day, mefloquine was not administrated; instead artesunate (4 mg/kg body weight) was given together with 0.6 mg/kg body weight primaquine (2 tablets of 15 mg primaquine; Government Pharmaceutical Organization of Thailand). All doses were observed and patients were followed for 30 min. If patients vomited within 30 min of treatment, the dose was repeated. Anti-pyretic paracetamol and anti-emetic dimenhydrinate were administered if necessary. Patients were requested to return for follow-up on days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 42, or if the patient experienced fever or malaria symptoms. Parasites were counted (Giemsa-stain) at each visit, and general symptoms were recorded.

Genotyping was performed on paired samples of P. falciparum DNA to distinguish between re-infection and recrudescence [12]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) restriction fragment length polymorphism was used to detect mutations in the following molecular markers (coding for mefloquine resistance): P. falciparum multi-drug resistance 1 (pfmdr 1-N86Y, pfmdr 1-Y184F, pfmdr 1-S1034C, pfmdr 1-N1042D, and pfmdr 1-D12467), P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (pfcrt-K67T, pfcrt-A220S, pfcrt-Q271E, pfcrt-N326S, pfcrt-I356T, and pfcrt-R371I), and P. falciparum ATPase 6 (atp 6-L263E, atp 6-E431K, atp 6-N569K, and atp 6-A623E) [13,14,15]. The pfk13 sequencing was performed at K13-propeller domain (codons 440–680, 720 bp) [16]. The pfmdr1 gene copy number was determined by SYBR Green I real-time PCR [17].

Blood samples for pharmacokinetic study

Blood samples (1 ml of whole blood) were collected into sodium heparinized tubes before and after the first dose (at 1, 2, 6, 12, 24, 25, 36, 37, 48, and 49 h post-dose and on day 3, 7, 12, 14, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35, and 42 post-dose) for determination of mefloquine concentrations. Collected samples were stored at − 20 °C until transported to Centre of Excellence in Pharmacology and Molecular Biology of Malaria and Cholangiocarcinoma, Chulabhorn International College of Medicine, Thammasat University. All samples were stored at − 80 °C until drug quantification.

Drug quantification

Mefloquine concentrations were quantified using liquid chromatography according to a previously published method [18]. The coefficient of variation for quality control samples was less than ± 5%. The lower limit of quantification (LOQ) was 2 ng/ml, and the lower limit of detection (LOD) was 0.5 ng/ml.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The natural logarithm of quantified mefloquine concentrations was analysed to derive pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. A non-linear mixed-effect modelling approach was utilized using the NONMEM v7.3 software [19]. Various supporting software were applied for graphics diagnostics and facilitation of modelling. The R v3.2.0 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and the package Xpose v4.6.1 were used for graphical diagnostics, while Pirana v2.9.2 and Perl-speaks-NONENMEM v4.6.0 were used to facilitate the modelling process [20,21,22,23].

Individual parameter estimates were assumed to be log-normally distributed by adding between-subject variability with an exponential model according to Eq. (1) and the structural model best describing the mefloquine concentration data were evaluated.

where Pi is the individual parameter estimate, θP is the typical value of parameter P, and ηi,P is the inter-individual variability for parameter P and patient is was drawn from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance ω2.

One-, two-, and three-compartment disposition modelswere evaluated to describe the absorption phase. A first-order absorption, a first-order absorption with the lag-time model, and a transit compartment model (1–13 transit compartments) with the absorption rate and rates between transit compartments were either assumed to be equal or estimated separately [24]. Between dose–occasion variability was investigated on absorption parameters according to Eq. (2):

where Pi,occ is the individual parameter estimate at occasion O, and κO,P is the between-occasion variability of parameter P at occasion O drawn from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance Π2.

The model was parameterized as follows: apparent elimination clearance (CL/F), central volume of distribution (Vc/F), inter-compartmental clearance(s) (Q/F), peripheral volume of distribution(s) (Vp/F), and mean transit time of the absorption phase (MTT).

Body weight was evaluated as an allometric function on all clearance and volume of distribution parameters. The exponents were fixed to 0.75 for clearance parameters and 1 for volume parameters based on previous reports [25, 26]. Other available covariates (e.g., body weight as a linear function, gender, and admission parasitaemia) were evaluated in a step-wise covariate search. In the forward step, the covariates were included with a statistical significance level of 0.01. The backward step was more stringent with a significance level of 0.001. In addition to the previously described covariates, validated molecular markers for mefloquine resistance and in addition, artemisinin resistance, were evaluated as covariates in the pharmacokinetic model.

Discrimination between two hierarchical models was based on the difference in objective function value (OFV), which is proportional to − 2 times the log-likelihood. The OFV was assumed to be Chi squared distributed resulting in a drop in OFV of 3.84 and 10.8 to be significant at statistical significance levels of 0.05 and 0.001, respectively.

Model fit was also evaluated using goodness-of-fit plots by plotting observations against the population and individually predicted concentrations and conditionally weighted residuals against population predicted concentrations and time after dose [27]. The performance of the model was evaluated with a visual predictive check [28], and shrinkage was calculated to evaluate individual estimates [29]. Parameter precision was calculated based on the result of 1000 resampled bootstrap datasets.

Results

Pharmacokinetic model

Population pharmacokinetic analysis of mefloquine was performed in 129 Burmese patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria with a total of 653 data points. Thirty-six patients had the re-appearance of parasitaemia during days 21–40 of the 42-day follow-up period, and 93 patients had the sensitive response. Patient demographic data are summarized in Table 1. Baseline mefloquine concentrations were present in 5 patients (3.88%), and these measurements were ignored. Whole blood mefloquine concentration–time profiles were described by a two-compartment disposition model, which was superior to a one-compartment disposition model (p < 0.05). Adding on one additional disposition model was not significant (p > 0.05). The absorption phase was described by 1 transit compartments; this absorption model was superior to the other tested absorption models (p < 0.05). Estimating the transit rate constant and the absorption rate constant separately resulted in a significantly improved model (p < 0.01). However, it also resulted in a model with a low precision in the estimation of the apparent volume of distribution of the central compartment (a relative standard error of 46.9% based on 300 bootstrap runs). The addition of relative bioavailability (F) fixed to 100% with an estimated inter-individual variability did not significantly improve the model and was excluded from the final model (p < 0.05). The addition of allometrically scaled body weight (exponent fixed to 0.75 and 1) did not improve the model and was not kept in the final model. Finally, the addition of between-occasion variability on the absorption parameters did not improve the model and was therefore excluded from the final model.

Covariates were investigated in a step-wise manner using the SCM functionality in Perl-Speaks-NONMEM. Of the covariates investigated (body weight, gender, and admission parasitaemia), none was found significant. Of the investigated molecular markers of mefloquine resistance and kelch-13 mutations, only the pfmdr1-D12467 was found to have a significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. However, the increased relative bioavailability (before this parameter was excluded) found in patients with mutated parasites was deemed unlikely and was excluded from the final model. Significant differences in maximum concentration (Cmax) and elimination half-life (t1/2) were found in patients who had treatment failure (36 cases) compared to patients with successful treatment (107 cases).

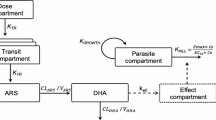

A graphical representation of the final model is presented in Fig. 1. The models exhibited good predictive performance as can be seen in the goodness-of-fit plots and the visual predictive check (Figs. 2 and 3). A small trend was found in the residual plots for the late time point, probably due to the censoring of the data (lower limit of quantification). The visual predictive check indicated that this model exhibits good predictive performance. The parameters estimates, shrinkage, and parameter precision are presented in Table 2. Secondary parameters, i.e., Cmax, time to maximum concentration (tmax), area under the concentration–time curve (AUC), and t1/2 are presented in Table 3.

Graphical representation of the final model describing the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. ktr is the rate constant between absorption compartments, CL is the apparent elimination clearance, Vc is the apparent volume of distribution of the central compartment, Q is the inter-compartmental clearance between the central and peripheral compartment, and Vp is the apparent volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment

Goodness-of-fit of the final mefloquine model. Top left: observed concentration against population concentrations. Top right: observed concentrations against individually predicted concentrations. Bottom left: the conditional weighted residual against population prediction. Bottom right: the conditional weighted residual against time after the dose

The visual predictive check of the final mefloquine model. Grey circles represent the observed concentrations. The solid black line represents the 50th percentile (median) of the observed data; the dashed lines represent the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the simulated 5th, 50th, and 95th percentile. The inset shows the absorption phase, between 0 and 100 h

Discussion

Mefloquine has had a history of resistance development, but has been successfully used in Thailand in combination with artesunate [30, 31]. With the emergence of artemisinin and piperaquine resistance, mefloquine is reconsidered to be used in triple combination or as a substitute for dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine. It is therefore of importance to have access to population pharmacokinetic models for mefloquine describing the change in concentration over time [32, 33]. In a previous report on the same clinical study as the present analysis [9], low mefloquine exposure was shown to contribute to treatment failure following a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine combination. In this study, 7 cases with reduced sensitivity to mefloquine in combination with the changes in pharmacokinetics of either mefloquine and/or artesunate were identified. Two of these patients had resistance to mefloquine alone, while 5 had resistance to mefloquine combined with reduced sensitivity to the artemisinin derivative. Pharmacokinetic factor alone contributed to recrudescence in 3 cases, all of which had inadequate whole blood mefloquine levels during the first 7 days of treatment (AUC0–7days). Drug concentrations capable of killing the parasite (above 500 μg/l) must be achieved for at least 3–4 parasite multiplication cycles (7 days) to be confident that cure will be achieved [34]. In this study, it was not possible, due to insufficient power, to identify covariates that contribute to the variability in the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. To investigate this further, a more detailed population pharmacokinetic approach was used. The current method provides estimates of mefloquine pharmacokinetic parameters and the variability between patients.

The present study describes the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine with individual parameter estimates using a non-linear mixed effect model. The pharmacokinetics of mefloquine was well described with a two-compartment model. This is in agreement with that previously reported [35,36,37,38]. Although some previously published models applied a one-compartment model to describe the concentrations of mefloquine over time [39,40,41], the present model resulted in a median mefloquine elimination half-life of 9.79 days, which is in agreement with previous studies. The different choices of distribution model are probably due to different study design and different amount of data in the elimination phase.

The mefloquine dose of 25 mg/kg of body weight was split into a 15 mg/kg dose followed by 10 mg/kg body weight dose to improve oral bioavailability and tolerability [42]. In the current study, mefloquine was well absorbed using this split-dose regimen. The absorption phase in the present model was described by one-transit compartment which successfully described the absorption phase. Previous models for mefloquine have primarily applied a first-order absorption model. However, the one-transit compartment has previously been identified in one study [36]. A transit-compartment model describes the observed lag-time in the absorption with the physiologically plausible model. Between dose and occasion variability was evaluated for absorption parameters to evaluate within individual variability and also to see if any trend in changing parameter estimates over time could be found. This is, for example, the case for piperaquine in which the relative bioavailability increases at later dose occasion [43, 44]. In the present study, this was not the case for mefloquine, and the absorption can be assumed to remain constant while the patients recovered from the disease.

Between-occasion variability has previously been identified on elimination clearance of mefloquine [38]. However, the study was performed over 6 months with 3 separate dosing occasions. The present study was performed over a 3-day period, and it was deemed highly unlikely that elimination clearance would change over the 3 doses. Therefore between-occasion variability on elimination clearance was not evaluated.

Parameter estimates of mefloquine population pharmacokinetics were similar to that previously published, and all parameters could be estimated with reasonable precision, indicating a stable model [37,38,39,40,41,42]. Shrinkage was low for all parameters except the inter-compartmental clearance, which was relatively high (50.8%). A trend could be seen in the conditional weighted residuals versus time after dose plot at late time points; this trend is a result of the last samples points which were quite low in this study.

Several covariates were investigated in the model. Body weight with fixed allometric exponents was investigated but was not found significant. The pharmacokinetics of several anti-malarial drugs, including piperaquine are affected by the body weight of the patients [43]. For mefloquine, some studies have identified an impact on body weight [35,36,37, 40]. In the present study however, no children were included, which explains why body weight was not identified as a significant covariate. Additional clinical studies including children of all ages would be useful to fully determine the impact of body weight on the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. In addition to body weight, previous studies identified an effect of haematocrit and history of fever as covariates on the elimination clearance. Also, body temperature, haematocrit level, history of fever, the presence of malaria infection, and mixed species malaria infection were identified as significant covariates for the volume of distribution [34, 36, 40]. In the present study, information on haematocrit level and body temperature were not available for analysis and were therefore not included in the covariate search. All participants included in the study already had mono-infection with P. falciparum, and the impact of mixed infection was not evaluated. Admission parasitaemia was however, evaluated on all parameters and was not found significant. Validated molecular markers for mefloquine resistance were investigated to evaluate if any of those would affect the pharmacokinetic properties of mefloquine. The only marker retained after the backward step was pfmdr 1-D12467, estimating an increased relative bioavailability in mutated patients. This was deemed as an unlikely scenario from a biological standpoint and was not included in the final model. In addition, the analysis showed that mutation of the Kelch-13 propeller did not affect the pharmacokinetic parameters of mefloquine. The significant influence of artesunate administration on mefloquine pharmacokinetics is unlikely [45, 46] and was not included in the analysis.

The model was also used to derive the secondary parameters, identifying a significant difference in maximum concentration and elimination half-life between patients who had treatment failure and patients with successful therapy. This could indicate a different volume of distribution in these two groups. However, none of the available covariates successfully described this difference and additional more extensive studies are needed to evaluate why this difference was seen.

Conclusion

This study successfully describes the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine following a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria from Thailand. A model has been developed which adequately describes the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. The developed model supports the previously published two-compartment models and a one-transit compartment absorption model. The differences in the maximum concentration and elimination half-life were also identified between patients with successful treatment and those with recrudescence. More extensive clinical studies including both adults and children are needed to fully characterize the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine.

References

WHO. World Malaria Report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/malaria.

WHO. World Malaria Report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. http://www.who.int/malaria.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. http://www.who.int/malaria/docs/TreatmentGuidelines2006.pdf.

White NJ. Malaria. In: Manson’s Tropical Diseases 22nded. Cook G, Zumla A, eds. London: Saunders; 2009.

Dondorp AM, Smithuis FM, Woodrow C, Seidlein LV. How to contain artemisinin- and multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:353–63.

Nosten F, Luxemburger C, ter Kuile FO, Woodrow C, Eh JP, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, et al. Treatment of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria with 3-day artesunate–mefloquine combination. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:971–7.

Malaria Division of Thailand. Guideline for treatment of malaria in Thailand, 2016.

Shanks GD, Edstein MD, Jacobus D. Evolution from double to triple-antimalarial drug combinations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:182–8.

Na-Bangchang K, Muhamad P, Ruaengweerayut R, Chaijaroenkul W, Karbwang J. Identification of resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate–mefloquine combination in an area along the Thai–Myanmar border: integration of clinico-parasitological response, systemic drug exposure, and in vitro parasite sensitivity. Malar J. 2013;12:263.

WHO. Assessment and monitoring of antimalarial drug efficacy for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria(WHO/HTM/RBM/2003.50). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

WHO. Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:1–90.

Cattamanchi A, Kyabayinze D, Hubbard A, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Distinguishing recrudescence from reinfection in a longitudinal antimalarial drug efficacy study: comparison of results based on genotyping of msp-1, msp-2, and glurp. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:133–9.

Duraisingh MT, Jones P, Sambou I, von Seidlein L, Pinder M, Warhurst DC. The tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with increased sensitivity to the antimalarials mefloquine and artemisinin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;108:13–23.

Duraisingh MT, Cowman AF. Contribution of the pfmdr1 gene to antimalarial drug-resistance. Acta Trop. 2005;94:181–90.

Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, et al. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol Cell. 2000;6:861–71.

Ferreira I, do Rosário VE, Cravo P. Real-time quantitative PCR with SYBR Green I detection for estimating copy numbers of nine drug resistance candidate genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2006;5:71.

Ménard D, Khim K, Beghain J, Adegnika AA, Shafiul-Alam M, et al. Worldwide map of Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2453–64.

Karbwang J, Molunto P, Na Bangchang K, Bunnag D. Determination of mefloquine in biological fluids using high performance liquid chromatography. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1989;20:55–60.

Boeckman A, Sheiner L, Beal S. NONMEM Users Guide. NONMEM Proj Group: Univ California; 2010. p. 1–61.

Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. Xpose–an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;58:51–64.

Lindbom L, Ribbing J, Jonsson EN. Perl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN)–a Perl module for NONMEM related programming. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2004/06/24 ed. 2004;75:85–94.

Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN. PsN-Toolkit–a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79:241–57.

Keizer RJ, van Benten M, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Huitema ADR. Piraña and PCluster: a modeling environment and cluster infrastructure for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;101:72–9.

Savic RM, Jonker DM, Kerbusch T, Karlsson MO. Implementation of a transit compartment model for describing drug absorption in pharmacokinetic studies. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:711–26.

Anderson BJ, Holford NH. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:303–32.

Anderson BJ, Holford NHG. Mechanistic basis of using body size and maturation to predict clearance in humans. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24:25–36.

Hooker AC, Staatz CE, Karlsson MO. Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES): a model diagnostic for the FOCE method. Pharm Res. 2007;24:2187–97.

Holford N: A degenerative predictive check. In: Population approach group Europe. Pamplona; 2005.

Savic RM, Karlsson MO. Importance of shrinkage in empirical Bayes estimates for diagnostics: problems and solutions. AAPS J. 2009;11:558–69.

Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Luxemburger C, Webster HK, Edstein M, et al. Mefloquine-resistant falciparum malaria on the Thai–Burmese border. Lancet. 1991;337:1140–3.

Price RN, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Kham A, Brockman A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, et al. Artesunate versus artemether in combination with mefloquine for the treatment of multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;89:523–7.

Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Mao S, Sopha C, et al. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:357–65.

Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–23.

Simpson JA, Price R, ter Kuile F, Teja-isavatharm P, Nosten F, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in patients with acute falciparum malaria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66:472–84.

Jullien V, Valecha N, Srivastava B, Sharma B, Kiechel J-R. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine, administered as a fixed-dose combination of artesunate–mefloquine in Indian patients for the treatment of acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2014;13:187.

Reuter SE, Upton RN, Evans AM, Navaratnam V, Olliaro PL. Population pharmacokinetics of orally administered mefloquine in healthy volunteers and patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:868–76.

Svensson USH, Alin H, Karlsson MO, Bergqvist Y, Ashton M. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modelling of artemisinin and mefloquine enantiomers in patients with falciparum malaria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58:339–51.

Charles BG, Blomgren A, Nasveld PE, Kitchener SJ, Jensen A, Gregory RM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in military personnel for prophylaxis against malaria infection during field deployment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:271–8.

Staehli Hodel EM, Guidi M, Zanolari B, Mercier T, Duong S, Kabanywanyi AM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine, piperaquine and artemether–lumefantrine in Cambodian and Tanzanian malaria patients. Malar J. 2013;12:235.

Ashley EA, Stepniewska K, Lindegardh N, McGready R, Hutagalung R, Hae R, et al. Population pharmacokinetic assessment of a new regimen of mefloquine used in combination treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2281–5.

Jamsen KM, Duffull SB, Tarning J, Lindegardh N, White NJ, Simpson JA. Optimal designs for population pharmacokinetic studies of the partner drugs co-administered with artemisinin derivatives in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2012;11:143.

ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Kyle D, Teja-Isavatharm P, Phaipun L, et al. Mefloquine treatment of acute falciparum malaria: a prospective study of non-serious adverse effects in 3673 patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:631–42.

Hoglund RM, Workman L, Edstein MD, Thanh NX, Quang NN, Zongo I. Population pharmacokinetic properties of piperaquine in falciparum malaria: an individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002212.

Tarning J, Rijken MJ, McGready R, Phyo AP, Hanpithakpong W, Day NPJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine in pregnant and nonpregnant women with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1997–2007.

Kerb R, Fux R, Mörike K, Kremsner PG, Gil JP, Gleiter CH, Schwab M. Pharmacogenetics of antimalarial drugs: effect on metabolism and transport. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:760–74.

Rattanapunya S, Cressey TR, Rueangweerayut R, Tawon Y, Kongjam P, Na-Bangchang K. Pharmacokinetic interactions between artesunate–mefloquine and ritonavir-boosted lopinavir in healthy Thai adults. Malar J. 2015;14:400.

Authors’ contributions

RH and KN conceived and designed the experiments. RH performed data analysis. RR and KN collected blood samples for pharmacokinetic and molecular analysis. KN and RH drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of the study protocol was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand (MOPH 009/2010). Written informed consents were obtained from all patients before study.

Funding

The study was supported by Center of Excellence in Pharmacology and Molecular Biology of Malaria and Cholangiocarcinoma of Thammasat University, National Research Council of Thailand (NRC) and National Research University Project of Thailand (NRU), Office of Higher Education Commission of Thailand.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoglund, R.M., Ruengweerayut, R. & Na-Bangchang, K. Population pharmacokinetics of mefloquine given as a 3-day artesunate–mefloquine in patients with acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in a multidrug-resistant area along the Thai–Myanmar border. Malar J 17, 322 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2466-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2466-3