Abstract

Background

Concomitant use of anti-malarial and antiretroviral drugs is increasingly frequent in malaria and HIV endemic regions. The aim of the study was to investigate the pharmacokinetic interaction between the anti-malarial drugs, artesunate-mefloquine and the antiretroviral drug, lopinavir boosted with ritonavir (LPV/r).

Methods

The study was an open-label, three-way, sequential, cross-over, pharmacokinetic study in healthy Thai adults. Subjects received the following treatments: Period 1: standard 3-day artesunate-mefloquine combination; Period 2 (2 months wash-out): oral LPV/r 400 mg/100 mg twice a day for 14 days; and, Period 3: artesunate-mefloquine and LPV/r twice a day for 3 days. Sixteen subjects (eight females) were enrolled and pharmacokinetic parameters were determined by non-compartmental analysis.

Results

In the presence of LPV/r, artesunate Cmax and systemic exposure were significantly increased by 45–80 %, while the metabolic ratio of dihydroartemisinin to artesunate was significantly reduced by 72 %. In addition, mefloquine Cmax and systemic exposure were significantly reduced by 19–37 %. In the presence of artesunate-mefloquine, lopinavir Cmax was significantly reduced by 22 % but without significant change in systemic drug exposure. The 90 % CI of the geometric mean ratio (GMR) of AUC0−∞ and Cmax were outside the acceptable bioequivalent range for each drug. Drug treatments were generally well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Vertigo, nausea and vomiting were the most common adverse events reported.

Conclusion

The reduction in systemic exposure of all investigated drugs raises concerns of an increased risk of treatment failure rate in co-infected patients and should be further investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections remain major global health burdens [1]. In 2012, there was an estimated 207 million cases of malaria worldwide, leading to 627,000 deaths [2]. It was estimated that 35 million people were living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 2014 and despite significant improvements in HIV prevention and treatment, there were also 2.1 million new infections and 1.5 million HIV-related deaths worldwide [3]. Management of malaria and HIV co-infection is challenging with possible adverse pathological, clinical, pharmacological, and epidemiological interactions between malaria and HIV infections and treatments [4–12]. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as first-line treatment for acute, uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria [13]. A 3-day course of artesunate-mefloquine combination therapy is commonly used in Southeast Asia to cope with multidrug-resistant P. falciparum [13]. Artesunate is responsible for the initial rapid decline in parasites, while mefloquine persists in the body much longer than artesunate to kill the remaining parasites [13]. For HIV therapy, ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors (PIs) are currently recommended by WHO as part of second-line antiretroviral therapy for adults. Globally, lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) remains the most commonly used PI due to its availability as a fixed-dose combination and high genetic barrier to resistance [14].

Artesunate is primarily metabolized via esterase-mediated hydrolysis and cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2A6 enzyme to the active metabolite dihydroartemisinin [15]. Dihydroartemisinin is subsequently metabolized via uridinediphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) 1A8/9 and 2B7 and excreted in the bile [16]. Biotransformation of its combination partner mefloquine and LPV/r is via CYP3A4 [17–21]. Ritonavir is a potent inhibitor and/or inducer of CYP3A4 and several CYP3A4, CYP2B6 and CYP2D6 activities [22–25] and is a substrate for several membrane transporter proteins [24, 26]. The potential for pharmacokinetic drug interactions between ACT, notably artemether-lumefantrine and LPV/r has been documented [27]. The aim of the current study was to investigate the pharmacokinetic interactions between artesunate-mefloquine and LPV/r when given together in healthy Thai adults.

Methods

Subjects and study design

This was an open-label, three-way, sequential, cross-over, pharmacokinetic study in healthy adult volunteers. Inclusion criteria included: (1) males and non-pregnant females, (2) aged 15–55 years, (3) body weight 40–65 kg, (4) non-smokers and non-alcohol drinkers, and, (5) residents of Mae Sot district, Tak Province. Exclusion criteria were those with: (1) hepatic or renal diseases, (2) history of using any drug or herbal medicine within the past 14 days, except antipyretic or anti-emetic drugs, or, (3) history of intolerance to artesunate, mefloquine, lopinavir, and ritonavir. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained from each subject before study. The minimum requirement of the sample size for the study was 16 subjects based on a = 0.05, target power = 80 % (b = 0.02) and CV (coefficient of variation) of clearance of artesunate (the most variable drug) = 20 %. Consenting adults were screened for eligibility and a physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), and laboratory safety tests (haematology, biochemistry, urinalysis, and pregnancy status) were performed.

The study protocol was approved by the Institute for Development of Human Research Protection (IHRP) at the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand. Study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national and institutional standards.

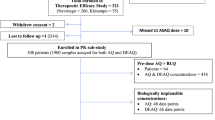

Drug administration

Figure 1 summarizes the study design. The pharmacokinetic sampling was performed sequentially on three occasions. Period 1: starting on Day 1, subjects received a 3-day course of oral artesunate-mefloquine (artesunate 200 mg on Days 1, 2, and 3 plus mefloquine 750 and 500 mg on Days 1 and 2, respectively). Artesunate doses were given as four tablets (50 mg artesunate per tablet, manufactured by Guilin Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., China). Mefloquine doses were given as three tablets on Day 1 and two tablets on Day 2 (250 mg mefloquine per tablet, manufactured by Atlantic Pharmaceutical Ltd., China). There was a 2-months wash-out period between Period 1 and Period 2. Period 2: subjects received oral doses of LPV/r (400/100 mg), twice daily, for 14 days (27 doses). There was no washout between Period 2 and Period 3. Period 3: subjects received the same 3-day oral artesunate-mefloquine combination as in Period 1 in combination with LPV/r 400/100 mg, twice a day for 3 days.

All subjects were admitted to Mae Sot General Hospital for observation during the pharmacokinetic sampling period and drug dosage was taken at least 2 h before meal with water (standard volume 150 mL). All drug doses were administered under supervision of the investigator team. Only analgesics/antipyretics (paracetamol) and anti-emetics (dimenhydrinate) were allowed in cases of fever and nausea. Drugs with potential interactions with the study drugs, i.e., inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 and CYP2A6 were disallowed during the study period [28, 29].

Assessments of safety and tolerability

Safety and tolerability of the drugs were assessed based on clinical and laboratory assessments during follow-up (42 days after Period 1 and 3, and 14 days after Period 2 according to NIH/NCI common toxicity criteria (CTC) grading system for adverse events [30]. Clinical assessments included physical examination and monitoring of vital signs and adverse events. Safety laboratory assessments (haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis) were performed during each period. All female subjects had a pregnancy test (b-human chorionic gonadotropin test) performed during each study period. Any abnormal laboratory result was followed up with repeat checks every week until it returned to normal.

Blood sample collection for pharmacokinetic assessment

During Period 1 (3-day artesunate-mefloquine alone) and Period 3 (3-day artesunate-mefloquine plus LPV/r), blood samples (3 mL each) for determination of mefloquine, artesunate and dihydroartemisinin concentrations were drawn at pre-dose (before the first dose), and at one, two, four, six, eight, 12, 24, 25, 30, 36, 48, and 49 h, and seven, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days post-dose (after the first dose). During Period 2 and Period 3, blood sample (3 mL each) for determination of lopinavir and ritonavir concentrations were drawn pre-dose (27th dose), and at one, two, four, six, eight, and 12 h post-dose. Immediately after collection, all blood samples were centrifuged (1200×g, 10 min) and the plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Measurement of drug concentrations

Analysis of plasma artesunate/dihydroartemisinin and mefloquine concentrations was performed at the Centre of Excellence in Pharmacology and Molecular Biology of Malaria and Cholangiocarcinoma, Thammasat University. Measurement of plasma concentrations of artesunate and its active plasma metabolite dihydroartemisinin were performed using liquid chromatography mass-spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), according to the methods of Thuy et al. and Lindegardh et al. with modifications [31, 32]. An Agilent 1260 LC system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) coupled with an API 5000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX, Foster City, USA), with a TurboVTM ionization source (TIS) interface operated in the positive ion mode, was used for the multiple reaction monitoring LC–MS/MS analysis. TIS temperature was maintained at 500 °C and the TIS voltage was set at 5500 V. Nitrogen gas was supplied from an AB-3G (Peak Scientific, Inchinnan, UK). The curtain, nebulizer (GS1) and TIS (GS2) gases were set at 25, 45 and 50 psi, respectively. Quantification was performed using selected reaction monitoring for the transitions m/z 402 → 267 (artesunate), 302 → 163 (dihydroartemisinin), and 300 → 209 (the internal standard artemisinin). Chromatographic separation was performed using an Elipse XDB C18 column (5 µm, 4.6 mm × 150 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) protected with an Eclipse XDB-C8 guard column (Thermo Electron Corporation, MA, USA). The gradient mobile phase consisted of a mixture of 10 mM ammonium acetate with 0.1 % glacial acetic acid and acetonitrile running at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. Total run time was 12 min. The limit of quantification (LOQ) for artesunate and dihydroartemisinin were 1 and 2 ng/mL, respectively. Recoveries for both compounds were between 82–92 and 81–98 %, respectively. The intra- and inter-day coefficients of variation (% CV) of artesunate vs dihydroartemisinin were 0.7–4.7 vs 4.5–7.3 %; and 3.9–18.3 vs 4.9–23.1 %, respectively.

Measurement of plasma concentrations of mefloquine was performed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) according to the method of Karbwang et al. [33] with modifications. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Hypersil ODS column (5 µm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) protected with an Eclipse XDB-C8 guard column (Thermo Electron Corporation, MA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of phosphate buffer (adjusted to pH 2.8 with 1 M phosphoric acid), acetonitrile and methanol at a ratio of 40:30:30 % (v:v:v), running at the flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The UV detector was set at the wavelength of 220 nm. The assay LOQ was 2.5 ng/mL. Recovery varied between 83 and 94 %. The intra- and inter-day CV of mefloquine were 1.2–6.2 and 4.3–14.5 %, respectively.

Lopinavir and ritonavir plasma drug concentrations were measured using a validated HPLC assay at the PHPT Pharmacology Laboratory, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University [34]. The assay LOQ for lopinavir and ritonavir were 100 and 50 ng/mL, respectively. The recoveries of lopinavir and ritonavir were between 96–112 and 90–94 %, respectively. Intra- and inter-assay precisions were less than 4 % of the coefficient of variation. This laboratory participates in the NIAID Clinical Pharmacology Quality Assurance Programme Proficiency Testing [35].

Quality control (QC) samples for all drugs/metabolite under investigation were run in duplicate in each analytical batch at low, medium and high concentrations. Criteria for acceptability were four out of six of the QC analyses to lie inside 100 ± 15 % of the nominal values.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined using a non-compartmental analysis using WinNonLin software (version 6.3, Pharsights, Certara, USA). Concentrations of drugs lower than the LOQ levels were expressed as zero (undetectable). The Cmax (maximum concentration); tmax (time of maximum concentration) were determined by direct inspection of the plasma concentration–time data. AUC (area under the concentration–time curve) from time 0 to 12 (AUC0−12h), 0 to 24 (AUC0−24h), 0 to 48 (AUC0−48h), 0 to 168 (AUC0−168h) h, and total AUC (AUC0−∞) were calculated using the trapezoidal rule. The extrapolated AUC from the last sampling time to infinity was estimated from Ct/elimination rate constant (lz). lz was calculated from at least five concentration–time points of elimination phase. Apparent oral clearance (CL/F) was calculated as dose/AUC0−∞. Volume of distribution (Vz/F) was calculated as CL/F/lz, and the terminal half-life (t1/2z) was calculated as 0.693/lz. Metabolic ratio (MR) was defined as the ratio between AUC0−24h of dihydroartemisinin and artesunate. The geometric mean ratio (GMR: the ratio of the value of the parameter for the drug when used in combination vs the corresponding value for the drug used alone) and its 90 % CI were determined for each parameter. A clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interaction occurred whenever the 90 % CI for systemic exposure ratio fell entirely outside the equivalence range of 0.8–1.25 [36].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS version 16.0 (Gorichem, The Netherlands). Pharmacokinetic parameters are presented as median and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). Comparison of all pharmacokinetic parameters of artesunate, dihydroartemisinin, mefloquine, lopinavir, and ritonavir obtained during the two Periods (−1 vs −3 and −2 vs −3) were performed using Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test. Comparison of the frequency of subjects with adverse events between the two groups was performed using a Chi-square test. Statistical significance level was set at a = 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Subject characteristics

Sixteen healthy subjects (eight males and eight females) were included in the pharmacokinetic data analysis; one female subject withdrew from the study before Period 2 due to a positive urine pregnancy test. The median (95 % CI) of age and body weight in male vs female subjects was 31 (20–40) vs 29 (21–39) years and 60 (56–62) vs 49 (46–53) kg, respectively. All were healthy as verified by results of clinical, ECG and laboratory investigations (Table 1).

Pharmacokinetics of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin with and without lopinavir/ritonavir

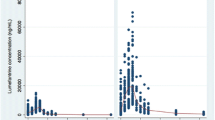

Median (95 % CI) plasma concentration–time profiles of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin following administration of a 3-day artesunate-mefloquine alone (Period 1) and in combination with LPV/r (Period 3) are shown in Fig. 2a, b). None had pre-dose level of either artesunate or dihydroartemisinin on any occasion. The extrapolated AUC of dihydroartemisinin from the last blood sampling time to infinity (AUCt−∞) was less than 5 %. The pharmacokinetic parameters of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin are summarized in Table 2. Inter-individual variation of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin plasma concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters (% CV) ranged from 69 to 400 and 64 to 289.6 %, respectively. Dihydroartemisinin plasma concentrations 1 h post-dose on Day 3 was significantly lower when artesunate was given with LPV/r [median (95 % CI) 310 vs 580 ng/mL, p = 0.044]. AUC0−∞, t1/2z, CL/F and Vz/F of artesunate could not be determined due to the rapid elimination of artesunate from the systemic circulation. High inter-individual variability in AUC0−24h for artesunate (54.4 %) and dihydroartemisinin (80.2 %) were observed. In the presence of steady-state LPV/r concentrations, artesunate AUC0–24h was significantly increased by about 80 % (p = 0.034), dihydroartemisinin Cmax, AUC0−24h and AUC0−∞ were significantly decreased by about 46.6, 58.2 and 48.8 %, respectively (p = 0.023, 0.002, and 0.006, respectively), while t1/2z was significantly increased by 148.5 % (p = 0.028). In addition, the metabolic ratio (AUC0–24h ratio) of dihydroartemisinin to artesunate was significantly reduced by 72.2 % (p = 0.001).

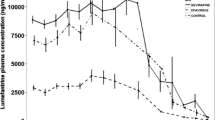

Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine with and without lopinavir/ritonavir

Median (95 % CI) plasma concentration–time profiles of mefloquine following administration of a 3-day artesunate-mefloquine alone (Period 1) and in combination with LPV/r (Period 3) are shown in Fig. 3a, b, and its pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 3. None had pre-dose level of mefloquine on any occasion. The extrapolated AUC of mefloquine from the last blood sampling time to infinity (AUCt−∞) was less than 10 %. In the presence of LPV/r, mefloquine Cmax, AUC0−48h, AUC0−168h and AUC0−∞ were significantly decreased by 19.3, 28.7, 37.1 and 35.2 %, respectively (p = 0.039, 0.001, 0.002 and 0.007, respectively), while Vz/F and CL/F were significantly increased by 37.9 and 54.6 %, respectively (p = 0.004 and 0.010, respectively). The inter-individual variability of plasma mefloquine concentrations ranged from 34.2 to 96.9 %.

Pharmacokinetics of lopinavir/ritonavir with and without artesunate-mefloquine

Median (95 % CI) plasma concentration–time profiles of LPV/r following the administration during Period 2 and 3 are shown in Fig. 4a, b. None had pre-dose level of lopinavir or ritonavir on any occasion. Three subjects in Period 1 and one subject in Period 3 had undetectable plasma lopinavir concentrations until 1 h after the first dose. One subject during Periods 1 and 3 each had undetectable plasma lopinavir concentrations until 1 h after the first dose in Periods 1 and 3. The extrapolated AUC of lopinavir or ritonavir from the last blood sampling time to infinity (AUCt−∞) was less than 5 %. The inter-individual variability of plasma lopinavir and ritonavir concentrations ranged from 50.6 to 127.6 and 21.3 to 62.9 %, respectively.

The pharmacokinetics of lopinavir and ritonavir alone (Period 2) and in combination with artesunate-mefloquine (Period 3) are summarized in Table 4. In the presence of artesunate-mefloquine, the Cmax of lopinavir was significantly decreased by 22.1 % (p = 0.03), while CL/F was significantly increased by 75.4 % (p = 0.023). The AUC0–12h, AUC0−∞ and Cmax, of ritonavir were significantly decreased by 44.6, 56.3 and 54.9 %, respectively (p = 0.003, 0.010, and 0.004, respectively), while CL/F and Vz/F were significantly increased by 129.1 and 80.4 %, respectively (p = 0.008 and 0.04, respectively).

Pharmacokinetic interaction between a 3-day artesunate-mefloquine and lopinavir/ritonavir

The 90 % CI of the GMR of Cmax for dihydrartemisinin, lopinavir, ritonavir, and mefloquine, AUC0−12h for ritonavir, AUC0−24h for artesunate and dihydroartemisinin, AUC0−168h for mefloquine, and AUC0−∞ for mefloquine and ritonavir were outside the acceptable bioequivalent range of 0.8-1.25 (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Safety and tolerability

Drug treatments were generally well tolerated. Only mild to moderate (NIH/NCI Grade 1 and 2) severity grade adverse events possibly related to the study drug(s) was observed. The frequency of adverse events occurred during the three periods were similar. The adverse events during Period 1 (artesunate-mefloquine combination) included vertigo (11 cases, 68.75 %), and nausea/vomiting (eight cases, 50 %). The adverse events observed during Period 2 (LPV/r) were diarrhoea (eight cases, 50 %) and vertigo (one case, 6.25 %). The adverse events observed during Period 3 (artesunate-mefloquine plus LPV/r) were vertigo (eight cases, 50 %), nausea/vomiting (two cases, 12.5 %), poor appetite (two cases, 12.5 %), and syncope (one case, 6.25 %). A markedly high proportion of subjects (11/16) with increased serum triglyceride (about 0.5–2.5 times of baseline) was observed during Period 2 after 28 doses of LPV/r.

Discussion

The present study is the first reporting the pharmacokinetic interactions between the artesunate-mefloquine and LPV/r. Marked changes in the pharmacokinetics of artesunate, dihydroartemisinin, mefloquine, lopinavir, and ritonavir were observed. All dose regimens during the three periods were relatively well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Vertigo, nausea and vomiting were the most common adverse event during artesunate-mefloquine in this study. The adverse events occurred during administration of LPV/r, diarrhoea and vertigo, were similar to previous observations [37–42]. Protease inhibitors have been commonly associated with the elevation of triglyceride in all age groups of HIV-infected patients [43, 44].

The disposition kinetics of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin were in general agreement with that observed in healthy Thai subjects [45]. Due to rapid clearance of artesunate from the systemic circulation, estimation of CL/F, Vz/F, and t1/2z were not possible. In addition, estimation of AUC0−∞ of artesunate is not accurate due to a large inter-individual variability of artesunate concentrations at the last sampling time point. A relative longer t1/2z of dihydroartemisinin was noted compared with a previous report (4.02 vs 0.74 h) [46]. Multiple factors complicate comparison of artesunate/dihydroarteminin pharmacokinetic findings across studies, including differences in assay sensitivities and blood sampling schedules. Additionally, the pharmacology of these agents is known to be different between patients with acute malaria and healthy volunteers. Mefloquine, a fluorinated 4-quinoline methanol compound, is moderately well absorbed orally in this split-dose regimen and extensively distributed. Its elimination was best described by biexponential disposition kinetics. The systemic exposure of mefloquine given as two divided doses of 750 and 500 mg 24 h apart appeared to be higher, i.e., ~two-fold relative to that observed in the previous study in healthy Thai subjects following mefloquine alone given at 750 and 500 mg 6 h apart [47, 48]. This was attributed to a relatively smaller Vz/F (40 %) and lower CL/F (33.4 %) in the current study population. Previous studies have shown that different mefloquine products are not bio-equivalent [49, 50]. Furthermore, mefloquine concentrations in plasma and whole blood have been shown to be different [51, 52]. Direct comparison of pharmacokinetics particularly systemic exposure should therefore be made with caution. The pharmacokinetics of lopinavir and ritonavir were in agreement with published data in HIV-negative volunteers [53].

Two studies have reported the pharmacokinetic dug-drug interactions between artesunate-based combinations with antiretrovirals drug. In the presence of steady-state nevirapine-based HIV-antiviral therapy, AUC0−∞ of artesunate was increased 1.5-fold, while Vz/F and CL/F were decreased [54]. In contrast, steady-state ritonavir concentrations significantly reduced the AUC0−∞ and Cmax of dihydroartemisinin in healthy subjects [55]. It was thought that the influence of mefloquine on pharmacokinetics of artesunate/dihydroartemisinin would only be minimal, if any [47]. The apparent decrease in systemic exposure of mefloquine in the presence of LPV/r could not be explained by the inhibitory effect of LPV/r on CYP3A4-mediated mefloquine metabolism [56]. Ritonavir was found to minimally affect mefloquine pharmacokinetics despite its strong inhibitory activity on CYP3A4 following a single 200 mg dose in healthy volunteers [56]. On the other hand, ketoconazole, the CYP3A4 inhibitor was found to increase plasma mefloquine concentrations in healthy subjects when co-administered at the dose of 400 mg daily for 10 days [57].

Based on available information, mefloquine does not interact with many compounds, although in vitro data suggested that it is a substrate and inhibitor of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein [17, 58, 59] and animal data indicated that it reduces bile production in rats [60]. Since both mefloquine and LPV/r are substrates of CYP3A4, the decrease in systemic exposure together with an increase in total oral clearance without a change in t1/2z of mefloquine may suggest the possibility of an inducing effect of LPV/r on the intestinal P-glycoprotein [61, 62] and/or a decrease in intestinal absorption of mefloquine. The increases in CL/F and Vz/F of mefloquine are of similar magnitude, whereas t1/2z is unchanged. This supports a decrease in mefloquine bioavailability due to LPV/r. The significant decrease in mefloquine Cmax and the similarity in magnitude of the increases in CL/F and Vz/F of mefloquine without change in t1/2z may also support this supposition.

The decrease in systemic exposure of both lopinavir and ritonavir was also unexpected in the light of report on the inhibitory effect of mefloquine on CYP3A4 [17]. Ritonavir auto-induction would be expected to be relatively low, but a decrease in intestinal absorption as a consequence of inhibitory effect of both mefloquine and ritonavir on bile production is possible [23, 60, 63]. Furthermore, because ritonavir is a substrate of P-glycoprotein [64], induction of gut P-glycoprotein by mefloquine and/or carboxymefloquine may contribute to the decreased drug absorption. In a previous study [56], ritonavir steady-state AUC was significantly decreased by mefloquine without any change in t1/2z following multiple dosing.

The systemic exposure of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin were changed in opposite direction in the presence of LPV/r (increased artesunate and decreased dihydroartemisinin exposure), and thus did not support the inducing activity of carboxymefloquine on CYP2A6-mediated artesunate metabolism [15]. The decrease in dihydroartemisinin AUC0-24 h when expressed as nmol h/mL unit is much greater than (about 180 %) the increase in artesunate AUC which stronger support on induction of DHA clearance by LOP/r. The contribution of mefloquine on disposition of artesunate/dihydroartemisinin was unlikely [47]. In addition, it was noted however that the term ‘metabolic ratio’ may not be the best to describe the rate of disappearance of artesunate in plasma as it may be contributed to by transport proteins. It should be pointed out that the observed systemic exposure of dihydroartemisinin may reflect both the absorption of artesunate, with subsequent conversion to dihydroartemisinin through first-pass or systemic metabolism, as well as direct absorption of dihydroartemisinin following its formation in the gut through acid-dependent chemical hydrolysis [65].

A large reduction in systemic exposure of both the anti-malarial artesunate-mefloquine and the antiretroviral LPV/r raises concerns regarding the higher risk of treatment failure of both malaria and HIV infection when artesunate-mefloquine and LPV/r are co-administered. The influence of disease factors (both malaria and HIV) add more complexity on the interaction [18, 66–68]. On the parasitological aspect, in vitro studies suggest that antiretroviral protease inhibitors may also possess anti-malarial activity [69–72] and could potentiate the efficacy of anti-malarial drugs [73–75]. Combination of mefloquine with ritonavir was shown to produce synergistic anti-malarial activity against D10 and FAC8 P. falciparum clones in vitro [69]. The most concerning finding is a 50 % reduction in the AUC of dihydroartemisinin and a significant decrease in Day 7 exposure of mefloquine. Artesunate and dihydroartemisinin (three- to four-fold potency of artesunate) play an important role the first phase of malaria therapy by rapidly lowering the parasite burden. Therefore, any decrease in dihydroartemisinin exposure as a consequence LPV/r co-administration may increase the risk of delayed parasite clearance, particularly given recent evidence of resistance to the artemisinins emerging in Southeast Asia [76]. Current guidelines from the WHO for treatment of uncomplicated malaria emphasize the need for 3 days of adequate ACT exposure to ensure elimination of parasites [13, 77]. Given that HIV/malaria co-infected patients present with higher parasite counts [8, 78], any reduction in dihydroartemisinin exposure may predispose patients to develop severe malaria due to slower parasite clearance. On the other hand, the reduction in systemic clearance of mefloquine would increase the risk of parasite recrudescence and/or re-infection. The Day 7 whole blood mefloquine concentration has proved to be a useful and simple surrogate for therapeutic efficacy of mefloquine [79].

Conclusion

Significant changes in the pharmacokinetics of artesunate/dihydroartemisinin, mefloquine and LPV/r were observed in the current study. Despite some limitations of the studies (small sample size, no measurement of carboxymefloquine and free drug concentrations), these data do provide valuable insights into the potential pharmacokinetic interactions when artesunate-mefloquine is co-administered with LPV/r in adults. The complex interaction unexplained by the metabolic behaviour (both parent drugs and metabolites) may suggest the involvement of multiple drug metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Studies in the target population (HIV and malaria co-infection) are needed for more conclusive clinical relevance and mechanistic explanation. Until this information is available, extrapolating these findings to the target population should be performed with caution.

References

Hochman S, Kim K. The impact of HIV and malaria coinfection: what is known and suggested venues for further study. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009(617954):9.

WHO. World malaria report. World Health Organization. Geneva: Switzerland; 2013.

UNAIDS. World AIDS day report 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/ campaigns/World-AIDS-Day-Report-2014/factsheet. Accessed 12 Jan 2015.

Brentlinger PE, Behrens CB, Kublin JG. Challenges in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of malaria in human immunodeficiency virus infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1827–36.

Flateau C, Le Loup G, Pialoux G. Consequences of HIV infection on malaria and therapeutic implications: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:541–56.

Abu-Raddad LJ, Patnaik P, Kublin JG. Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Science. 2006;314:1603–6.

Kublin JG, Patnaik P, Jere CS, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Chimbiya N, et al. Effect of Plasmodium falciparum malaria on concentration of HIV-1-RNA in the blood of adults in rural Malawi: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;365:233–40.

Whitworth J, Morgan D, Quigley M, Smith A, Mayanja B, Eotu H, et al. Effect of HIV-1 and increasing immunosuppression on malaria parasitaemia and clinical episodes in adults in rural Uganda: a cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1051–6.

French N, Nakiyingi J, Lugada E, Watera C, Whitworth JA, Gilks CF. Increasing rates of malarial fever with deteriorating immune status in HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults. AIDS. 2001;15:899–906.

Cohen C, Karstaedt A, Frean J, Thomas J, Govender N, Prentice E, et al. Increased prevalence of severe malaria in HIV-infected adults in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1631–7.

Chalwe V, Mukwamataba D, Menten J, Kamalamba J, Mulenga M, D’Alessandro U. Increased risk for severe malaria in HIV-1-infected Adults, Zambia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:749–55.

Patnaik P, Jere CS, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Wirima J, Pendame R, et al. Effects of HIV-1 sero-status, HIV-1 RNA concentration, and CD4 cell count on the incidence of malaria infection in a cohort of adults in rural Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:984–91.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Sungkanuparpha S, Techasathitb W, Utaipiboonc C, Chasombatd S, Bhakeecheepe S, Leechawengwongs M, et al. Thai national guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents 2010. Asian Biomed. 2010;4:515–8.

Li XQ, Bjorkman A, Andersson TB, Gustafsson LL, Masimirembwa CM. Identification of human cytochrome P(450)s that metabolise anti-parasitic drugs and predictions of in vivo drug hepatic clearance from in vitro data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:429–42.

Ilett KF, Ethell BT, Maggs JL, Davis TM, Batty KT, Burchell B, et al. Glucuronidation of dihydroartemisinin in vivo and by human liver microsomes and expressed UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:1005–12.

Na-Bangchang K, Karbwang J, Back DJ. Mefloquine metabolism by human liver microsomes. Effect of other antimalarial drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1957–61.

Eagling VA, Back DJ, Barry MG. Differential inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoforms by the protease inhibitors, ritonavir, saquinavir and indinavir. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;14:190–4.

Sevrioukova IF, Poulos TL. Structure and mechanism of the complex between cytochrome P4503A4 and ritonavir. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18422–7.

Lakhman SS, Ma Q, Morse GD. Pharmacogenomics of CYP3A: considerations for HIV treatment. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1323–39.

Fontaine F, de Sousa G, Burcham PC, Duchêne P, Rahmani R. Role of cytochrome P450 3A in the metabolism of mefloquine in human and animal hepatocytes. Life Sci. 2000;66:2193–212.

Wyen C, Fuhr U, Frank D, Aarnoutse RE, Klaassen T, Lazar A, et al. Effect of an antiretroviral regimen containing ritonavir boosted lopinavir on intestinal and hepatic CYP3A, CYP2D6 and P-glycoprotein in HIV-infected patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:75–82.

Kumar GN, Jayanti VK, Johnson MK, Uchic J, Thomas S, Lee RD, et al. Metabolism and disposition of the HIV-1 protease inhibitor lopinavir (ABT-378) given in combination with ritonavir in rats, dogs, and humans. Pharm Res. 2004;21:1622–30.

Fukushima K, Kobuchi S, Mizuhara K, Aoyama H, Takada K, Sugioka N. Time-dependent interaction of ritonavir in chronic use: the power balance between inhibition and induction of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 3A. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:2044–55.

Khoo S, Back D, Winstanley P. The potential for interactions between antimalarial and antiretroviral drugs. AIDS. 2005;19:995–1005.

Tempestilli M, Elisei F, Cimini E, D’Avolio A, Grassi G, Nicastri E, et al. Low-density lipoprotein and ritonavir: an interaction between antiretrovirals and lipids mediated by P-glycoprotein. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1760–6.

Kiang TK, Wilby KJ, Ensom MH. Clinical pharmacokinetic drug interactions associated with artemisinin derivatives and HIV-antivirals. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:141–53.

Zhou SF. Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:310–22.

Pelkonen O, Rautio A, Raunio H, Pasanen M. CYP2A6: a human coumarin 7-hydroxylase. Toxicology. 2000;144:139–47.

Nation Institutes of Health. The NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). U.S. Department of Health and Human Service, USA, 2003.

le Thuy TD, le Hung N, Danh PT, Na-Bangchang K. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin in human plasma. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39:963–77.

Lindegardh N, Hanpithakpong W, Kamanikom B, Singhasivanon P, Socheat D, Yi P, et al. Major pitfalls in the measurement of artemisinin derivatives in plasma in clinical studies. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;876:54–60.

Karbwang J, Molunto P, Na Bangchang K, Bunnag D. Determination of mefloquine in biological fluids using high performance liquid chromatography. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1989;20:55–60.

Droste JA, Verweij-Van Wissen CP, Burger DM. Simultaneous determination of the HIV drugs indinavir, amprenavir, saquinavir, ritonavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, the nelfinavirhydroxymetabolite M8, and nevirapine in human plasma by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25:393–9.

DiFrancesco R, Tooley K, Rosenkranz SL, Siminski S, Taylor CR. Clinical pharmacology quality assurance for HIV and related infectious diseases research. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:479–82.

Food US, Administration Drug. Guidance for industry: drug interaction studies-study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations. Maryland: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2012.

Na-Bangchang K, Thanavibul A, Tippawangkosol P, Karbwang J. Pharmacokinetics of the four combination regimens of dihydroartemisinin/mefloquine in acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36:23–33.

AlKadi HO. Antimalarial drug toxicity: a review. Chemotherapy. 2007;53:385–91.

Agomo PU, Meremikwu MM, Watila IM, Omalu IJ, Odey FA, Oguche S, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of artesunate-mefloquine in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in four geographic zones of Nigeria. Malaria J. 2008;7:1–9.

Rendi-Wagner P, Noedl H, Wernsdorfer WH, Wiedermann G, Mikolasek A, Kollaritsch H. Unexpected frequency, duration and spectrum of adverse events after therapeutic dose of mefloquine in healthy adults. Acta Trop. 2002;81:167–73.

Hermes A, Squires K, Fredrick L, Martinez M, Pasley M, Trinh R, et al. Meta-analysis of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir-containing antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected women. HIV Clin Trials. 2012;13:308–23.

Kaplan SS, Hicks CB. Safety and antiviral activity of lopinavir/ritonavir-based therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:273–6.

Flexner C, Tierney C, Gross R, Andrade A, Lalama C, Eshleman SH, et al. Comparison of once-daily versus twice-daily combination antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naive patients: results of AIDS clinical trials group (ACTG) A5073, a 48-week randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1041–52.

Pulido F, Estrada V, Baril JG, Logue K, Schewe K, Plettenberg A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of fosamprenavir plus ritonavir versus lopinavir/ritonavir in combination with abacavir/lamivudine over 144 weeks. HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10:76–87.

Na-Bangchang K, Karbwang J, Congpoung K, Thanavibul A, Ubalee R. Pharmacokinetic and bioequivalence evaluation of two generic formulations of oral artesunate. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;53:375–80.

Na-Bangchang K, Krudsood S, Silachamroon U, Molunto P, Tasanor O, Chalermrut K, et al. The pharmacokinetics of oral dihydroartemisinin and artesunate in healthy Thai volunteers. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:575–82.

Karbwang J, Na Bangchang K, Thanavibul A, Back DJ, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine alone or in combination with artesunate. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:83–7.

Na-Bangchang K, Molunto P, Banmairuroi V, Thanavibul A, Karbwang J. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine when given as a single and two divided-dose regimens. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1995;15:215–20.

Na-Bangchang K, Karbwang J, Palacios P, Ubalee R, Saengtertsilapachai S, Wernsdorfer W. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence evaluation of three commercial tablet formulations of mefloquine when given in combination with dihydroartemisinin in patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;55:743–8.

Weidekamm E, Rusing G, Caplain H, Sorgel F, Crevoisier C. Lack of bioequivalence of a generic mefloquine tablet with the standard product. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:615–9.

Wernsdorfer WH, Noedl H, Rendi-Wagner P, Kollaritsch H, Wiedermann G, Mikolasek A, et al. Gender-specific distribution of mefloquine in the blood following the administration of therapeutic doses. Malar J. 2013;12:443.

Karbwang J, Looareesuwan S, Phillips RE, Wattanagoon Y, Molyneux ME, Nagachinta B, et al. Plasma and whole blood mefloquine concentrations during treatment of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria with the combination mefloquine-sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23:477–81.

Jackson A, Hill A, Puls R, Else L, Amin J, Back D, et al. Pharmacokinetics of plasma lopinavir/ritonavir following the administration of 400/100 mg, 200/150 mg and 200/50 mg twice daily in HIV-negative volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:635–40.

Fehintola FA, Scarsi KK, Ma Q, Parikh S, Morse GD, Taiwo B, et al. Nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy impacts artesunate and dihydroartemisinindisposition in HIV-infected Nigerian adults. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;703:604–5.

Morris CA, Lopez-Lazaro L, Jung D, Methaneethorn J, Duparc S, Borghini-Fuhrer I, et al. Drug-drug interaction analysis of pyronaridine/artesunate and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:489–95.

Khaliq Y, Gallicano K, Tisdale C, Carignan G, Cooper C, McCarthy A. Pharmacokinetic interaction between mefloquine and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:591–600.

Ridtitid W, Wongnawa M, Mahatthanatrakul W, Raungsri N, Sunbhaich M. Ketoconazole increases plasma concentrations of antimalarial mefloquine in healthy human volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:285–90.

Ayub M. TA S. Inhibition of human placental aromatase by mefloquine. J Steroid Biochem. 1988;29:149–51.

Riffkin CD, Chung R, Wall DM, Zalcberg JR, Cowman AF, Foley M, et al. Modulation of the function of human MDR1 P-glycoprotein by the antimalarial drug mefloquine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1545–52.

Coleman MD, Fleckenstein L, Heiffer MH. Primaquine disposition in the isolated perfused rat liver: effect of mefloquine induced bile flow reduction. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1989;10:153–64.

Foisy MM, Yakiwchuk EM, Hughes CA. Induction effects of ritonavir: implications for drug interactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1048–59.

Perloff M, Von Moltke LL, Marchand JE, Greenblatt DJ. Ritonavir induces P-glycoprotein expression, multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1), and drug transporter-mediated activity in a human intestinal cell line. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:1829–37.

Osterberg T, Norinder U. Theoretical calculation and prediction of P-glycoprotein-interacting drugs using Mol Surfparametrization and PLS statistics. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;10:295–303.

Profit L, Eagling VA, Back DJ. Modulation of P-glycoprotein function in human lymphocytes and Caco-2 cell monolayers by HIV-1 protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1999;13:1623–7.

Olliaro P, Nair N, Sathasivam K, Mansor S, Navaratnam V. Pharmacokinetics of artesunate after single oral administration to rats. BMC Pharmacol. 2001;1:12–6.

Fehintola FA, Akinyinka OO, Adewole IF, Maponga CC, Ma Q, Morse GD. Drug interactions in the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of malaria in HIV infected individuals in Sub Saharan Africa. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:51–6.

Karbwang J, Na-Bangchang K, Congpoung K, Thanavibul A, Harinasuta T. Pharmacokinetics of oral artesunate in Thai patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Clin Drug Invest. 1998;15:37–43.

Dickinson L, Khoo S, Back D. Differences in the pharmacokinetics of protease inhibitors between healthy volunteers and HIV-infected persons. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2008;3:296–305.

Skinner-Adams TS, Andrews KT, Melville L, McCarthy J, Gardiner DL. Synergistic interactions of the antiretroviral protease inhibitors saquinavir and ritonavir with chloroquine and mefloquine against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:759–62.

Parikh S, Gut J, Istvan E, Goldberg DE, Havlir DV, Rosenthal PJ. Antimalarial activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2983–5.

Hobbs CV, Tanaka TQ, Muratova O, Van Vliet J, Borkowsky W, Williamson KC, et al. HIV treatments have malaria gametocyte killing and transmission blocking activity. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:139–48.

Andrews KT, Fairlie DP, Madala PK, Ray J, Wyatt DM, Hilton PM, et al. Potencies of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors in vitro against Plasmodium falciparum and in vivo against murine malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:639–48.

He Z, Qin L, Chen L, Peng N, You J, Chen X. Synergy of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors with chloroquine against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro and Plasmodium chabaudi in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2653–6.

He Z, Chen L, You J, Qin L, Chen X. Antiretroviral protease inhibitors potentiate chloroquine antimalarial activity in malaria parasites by regulating intracellular glutathione metabolism. Exp Parasitol. 2009;123:122–7.

Li X, He Z, Chen L, Li Y, Li Q, Zhao S, et al. Synergy of the antiretroviral protease inhibitor indinavir and chloroquine against malaria parasites in vitro and in vivo. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:1519–24.

Na-Bangchang K, Karbwang J. Emerging artemisinin resistance in the border areas of Thailand. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:307–22.

WHO. Summary of product characteristics: Artesunate 25 mg + Mefloquine (as hydrochloride) 50 mg Tablets, (Cipla Ltd), MA078. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Berg A, Patel S, Aukrust P, David C, Gonca M, Berg ES, Dalen I, Langeland N. Increased severity and mortality in adults co-infected with malaria and HIV in Maputo, Mozambique: a prospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88257.

Na-Bangchang K, Ruengweerayut R, Mahamad P, Ruengweerayut K, Chaijaroenkul W. Declining in efficacy of a three-day combination regimen of mefloquine-artesunate in a multi-drug resistance area along the Thai-Myanmar border. Malar J. 2010;9:1475.

Authors’ contributions

KN was involved in providing the conception, design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. TC was involved in providing the conception, design of the study, and revised the manuscript. SR and RR performed data collection. SR and YT performed drug analysis. SR drafted the manuscript. PK performed statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by The National Research Council of Thailand, (Grant No. 034/2556), Commission on Higher Education (NRU Project), and Thammasat University (Centre of Excellence in Pharmacology and Molecular Biology of Malaria and Cholangiocarcinoma). SR receives financial support from the Office of the Higher Education Commission (OHEC) (Grant No. 036/554) for her PhD Programme Thai Doctoral degree, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University. We would like to thank all study participants in this study for theirs voluntary participant and members of the clinical trial study team of Mae Sot hospital.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Rattanapunya, S., Cressey, T.R., Rueangweerayut, R. et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between artesunate-mefloquine and ritonavir-boosted lopinavir in healthy Thai adults. Malar J 14, 400 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0916-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0916-8