Abstract

Liquid biopsy (LB) has boosted a remarkable change in the management of cancer patients by contributing to tumour genomic profiling. Plasma circulating cell-free tumour DNA (ctDNA) is the most widely searched tumour-related element for clinical application. Specifically, for patients with lung cancer, LB has revealed valuable to detect the diversity of targetable genomic alterations and to detect and monitor the emergence of resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, its non-invasive nature helps to overcome the difficulty in obtaining tissue samples, offering a comprehensive view about tumour diversity. However, the use of the LB to support diagnostic and therapeutic decisions still needs further clarification. In this sense, this review aims to provide a critical view of the clinical importance of plasma ctDNA analysis, the most widely applied LB, and its limitations while anticipating concepts that will intersect the present and future of LB in non-small cell lung cancer patients.

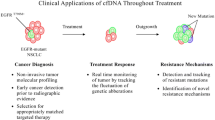

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is the second most prevalent cancer globally, corresponding to 11.4% of diagnosed cancers, according to GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates, and it is the first cause of cancer death, accounting for 18% of deaths [1]. In the majority of cases, it presents with advanced or metastatic disease [2].

Numerous actionable genomic alterations have been identified in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), particularly those with the adenocarcinoma subtype. As a result, targeted therapies have emerged, and LC treatment has become biomarker-driven [3, 4]. There are targeted treatments for genomic alterations in the ALK, BRAF, EGFR, ERBB2, KRAS, MET, NTRK, RET and ROS1 genes, configuring substantial improvements in patient's survival and quality of life [3, 4]. The first targeted drug was approved for patients with EGFR activating mutations occurring in the tyrosine kinase domain of the gene, present in 15–20% of Caucasian patients with lung adenocarcinoma and in 40% of Asians [5,6,7]. Deletions of exon 19 (del 19) and the substitution of the amino acid p.Leu858Arg in exon 21 (L785R) comprise about 80–90% of the mutation spectrum. Rarer variants can also occur in exons 18 and 20, but their association with treatment response is less consistent [5]. Presently, for treating patients with tumours harbouring activating mutations in the EGFR gene 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation TKIs are approved, differing from each other on the receptor affinity and selectivity to different variants and providing a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 10 to 19 months [8,9,10,11]. In about 50–60% of patients treated with 1st or 2nd generation TKIs, the acquired resistance mechanism is a p.Thr790Met point mutation (T790M) in the EGFR gene [12,13,14]. This mutation increases the receptor affinity for ATP binding, drastically reducing the drug activity [15]. Third-generation TKIs have emerged as selective for both EGFR activating and T790M resistance mutations [16] with superior activity than chemotherapy in patients whose disease progressed with the T790M [17]. Still, disease progression-associated mechanisms are heterogeneous and not fully understood, differing whether the 3rd generation TKI is used at the frontline or after progression on 1st or 2nd generation TKIs [18,19,20].

With different proportions, EGFR-dependent mechanisms include new tertiary mutations, such as the exon 20 C797S mutation, EGFR amplification or T790M disappearance. The EGFR independent mechanisms can occur with bypass pathway activation, such as ERB-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (HER2) and MET amplification, PIK3CA activating mutations, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) deletion, RAS mutations, and fusions affecting anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and ret-proto-oncogene (RET). Moreover, there is also the possibility of phenotypic alteration, such as small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) transformation [18,19,20].

ALK rearrangements occur in 3–5% of lung adenocarcinomas [21], consequent to an inversion on the short-arm of chromosome 2 joining its 3′ end with the 5′ end of the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4), resulting in an EML4-ALK chimeric protein [22]. Targeted therapy for patients with ALK rearrangements have significantly impacted prognosis, with patients treated with a sequence of TKIs achieving over five years of survival after diagnosis of metastatic disease [23]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors of different generations were developed, with relevant differences concerning ALK inhibitory potency, intracranial activity and efficacy on ALK mutations associated with resistance [24]. For patients with ALK fusions treated with TKIs, mutations in the ALK gene are one of the on-target resistance mechanisms. However, unlike EGFR, mutations are diverse and differ depending on each ALK inhibitor [25]. In addition, non-targeted alterations can occur alongside mutations and amplifications in different genes. For example, MET amplifications are present in about 15% of patients treated with new-generation TKIs, and histological transformation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) may also occur [26, 27]. Therefore, recognising genomic alterations is essential for the selection and sequencing of ALK inhibitors.

Similar good results have been obtained with TKIs for other molecular targets. For example, synergising a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor is indicated for NSCLC with BRAF p.V600E [3, 4]. For ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1), RET and neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (NTRK) fusions, highly effective TKIs are available, as for the MET exon14 skipping mutation [3, 4]. For ERBB2 mutations, TKIs and new antibody conjugates are being investigated [3]. The most recent advance in targeted therapy comprises the inhibition of the p.Gly12Cys mutation in the KRAS gene, one of the most frequent events in lung adenocarcinoma [3, 28].

In this sense, tumour genotyping is currently a fundamental element to determine the optimal treatment for each patient. Molecular tests are advised for untreated non-squamous NSCLC patients with advanced disease and others with clinical features linked to a greater probability of having driver mutations [4, 29]. Nonetheless, and despite is currently considered the gold standard, tissue biopsy is associated with numerous drawbacks. Tumour samples refer to small biopsies and cytology specimens obtained by invasive methods, as bronchoscopy, transthoracic biopsies, and pleural techniques. Also, not all tumour lesions are accessible, and tissue genotyping is linked to a 5–10% failure rate due to inadequate or insufficient DNA content [30]. In addition, tissue biopsies may not fully reflect tumour heterogeneity, as they are usually obtained from the most accessible tumour location site [31].

Over time, clinicians and researchers have pursued the idea of using non-invasive techniques for tumour diagnosis through a deeper study of peripheral blood and other fluids. Indeed, tumours release part of themselves into the circulation through the form of free nucleic acids, tumour cells, exosomes, among other elements, that can be extracted and analysed [32]. Fortunately, the advances stated in sequencing technologies have been a determinant step in making this ambition a reality.

Liquid biopsy (LB) is a non-invasive, easily taken, repeatable and less expensive technique than tissue biopsy and potentially reflects the heterogeneity of the genomic landscape, as it gets biological information from all tumour shedding sources [32]. A LB consists of analysing tumour-related biomarkers in body fluids, like blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural, pericardial effusions, and urine. It is a source of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA), circulating cell-free tumour DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumour cells (CTCs), exosomes, microRNAs, as well as proteins derived from cancer cells [32]. These components have distinct properties, potentialities and methods of capture and analysis, requiring further validation for clinical use, as briefly exposed in Table 1 [32,33,34,35,36].

Cell-free DNA has been the most studied component, with ctDNA being the portion of cfDNA delivered by the tumour [37]. In these DNA fractions released by tumour apoptosis and necrosis and some active secretion [38], mutations in cancer-associated genes, microsatellite instability, and epigenetic alterations have been identified [39]. Cell-free circulating tumour DNA represents less than 1% of cfDNA [40], requiring highly sensitive analytic methods [41, 42]. Different sequencing technologies have been developed to detect mutant DNA and have evolved to achieve higher performance. They can be broadly grouped into two approaches: digital PCR and NGS-based methods [39, 43]. Both approaches have strengths and limitations. PCR-based assays are highly sensitive, able to detect variants with a frequency as low as 0.01%, less expensive and straightforward than NGS, but restricted to the detection of limited pre-planned alterations [40, 44]. NGS approaches are more complex but allow the detection of multiple alterations in different genes simultaneously. They can embrace "whole" alterations or be selected for targeted panels, being this one the most used for clinical application due to the highest sensitivity, lower cost, and simplicity of interpretation. Generally, NGS techniques can be amplicon-based or hybrid-capture-based, accounting for differences in test performance and the range of alterations capable of being detected [39, 44].

In the NSCLC setting, LB, particularly ctDNA genomic analysis, has an expanding role in detecting oncogenic driver alterations as well as emerging resistance mechanisms [45]. Thus, considering the role of LB in the most relevant clinical scenarios, we aim to provide a critical view of its importance and limitations while anticipating concepts intersecting the present and future clinical uses of LB in NSCLC patients, considering our "real-world" experience towards LB implementation [46, 47]. Specifically, in this review, we will discuss the application of LB for genotyping LC in its most relevant scenarios, for detection of resistance-related mutations, disease monitoring, with a focus being also given to the future applications of LB, reflecting on results’ interpretation and pitfalls.

Circulating cell-free tumour DNA for detection of EGFR mutations

The detection of EGFR mutations, either activating or resistance-associated, is extremely relevant, given the link between EGFR mutations, treatment response and clinical outcomes. However, genetic testing for detection of EGFR mutations is not always successful, and re-biopsies display numerous difficulties, as previously mentioned. Before ctDNA genotyping is accepted as a surrogate for tissue genotyping, it is essential to reflect on the test accuracy and its predictive value as a biomarker for treatment selection. Several studies have addressed the analytical agreement between the mutational status assessed in plasma and tumour samples, and, in general, a robust correlation was found (Table 2). The meta-analysis (Table 3) published so far have demonstrated a sensitivity for detecting EGFR mutations ranging from 60 to 70% and a specificity of 80–98% [48,49,50,51,52,53]. Distinct studies with different technologies were included, that ultimately accounted for highly variable sensitivity values. For instance, when the effectiveness for detecting EGFR mutations with LB was addressed in a "real-world" setting, as in the multicentric studies, IGNITE and ASSESS [54, 55] (Table 2), plasma sensitivity was below 50%, with significant variability between centres and the technique used. Such findings reinforce the need to standardise procedures and validate techniques for large-scale implementation. The latest ultrasensitive sequencing technologies, such as digital PCR or plasma digital droplet PCR (ddPCR), use probes that allow the detection of del19 and L858R with very high sensitivity rates (greater than 80%) and specificity of 100% [56, 57] (Table 2). Moreover, it has become possible to analyse cfDNA by NGS, with advantages in sensitivity and wealth of information. Either amplicon-based [58, 59] or hybrid-capture sequencing [60, 61] have shown sensitivity reaching 94% and specificity exceeding 95% (Table 4).

The first data considering the predictive value of cfDNA for response to EGFR TKIs came from the trial comparing chemotherapy with a 1st generation TKI [62, 63]. Goto et al. [63] firstly found a significant correlation between cfDNA EGFR mutation status and PFS, and although the serum test had low sensitivity (43.1%), it opened the window for further investigation. The clinical utility of plasma EGFR mutation detection and the concordance between the mutational status in plasma and tissue were investigated in EGFR-mutated patients undergoing 1st line treatment with TKIs, with sensitivity, specificity, and concordance rates of 66.5, 99.8 and 94.3%, respectively [64]. Also, OS and PFS did not differ regardless of whether the mutation was detected in plasma or tissue [64, 65]. Besides that, plasma allowed the detection of additional cases that were not identified in the available tissue sample [64]. Likewise, in a retrospective analysis of a 1st generation TKI versus standard chemotherapy as 1st line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC, the plasma detection of EGFR mutations by real-time PCR showed a predictive capacity with an OS and PFS overlapping that of tissue [66]. These data were of enough robustness, demonstrating a strong association between detection of plasma mutations and response to TKIs, leading to the first approval of a LB for detecting EGFR mutations [67] (Table 5).

Patients with EGFR sensitising mutations treated with 1st or 2nd generation TKIs presented a profound overall response rate (ORR) around 60–70% but display a PFS of only 9 to 14 months [9, 10, 65]. The T790M mutation is the most frequent mechanism [12, 13] and is associated with response to 3rd generation TKIs [68], making detection crucial for selecting candidates for this treatment. In this context, re-biopsy is even more difficult, not succeeded in 20–30% of patients [69,70,71,72] due to inaccessible tumour localisation sites, patients’ fragility, or increased risk for tissue biopsies. Therefore, LB assumes a relevant role in progressive disease. The usefulness of plasma for detecting T790M mutation was addressed in studies exploring the activity of 3rd generation TKIs. As main findings, the plasma detection rate of the T790M ranged from 51 to 81%, with specificity ranging from 77 to 100% [73,74,75] (Table 2), and dPCR and NGS-based assays displayed a higher sensitivity over the Cobas test (Table 4) [60]. Besides, plasma identified T790M resistance mutations missed by tissue biopsy due to tumour heterogeneity or inadequate or unavailable tumour tissue [59].

Regarding the predictive value of finding a T790M mutation in plasma, the response rate was similar, whether the T790M was identified in the plasma or tumour (ORR: 63 vs 62%) [76], suggesting that in patients with a plasma T790M positive assay, tissue biopsy could be avoided. Considering the rate of false-negative results observed (30%), the negative plasma results justify further investigation [76]. Similar findings were stated with 3rd generation TKIs used in the 1st line [77]. The details of approved EGFR plasma detection assays [67, 78, 79] are shown in Table 5.

In patients treated with 3rd generation TKIs, several secondary resistance mechanisms may occur. The role of plasma genomic profiling of ctDNA was well documented in the trial where osimertinib was studied in patients with T790M-positive NSCLC. Out of the 73 patients included, 49% had no detectable T790M at progression, and 15% acquired an EGFR secondary mutation in C797S/G. Amplifications of MET, ERBB2, and Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha (PIK3CA) were detected in 19%, 5%, and 4% samples, respectively. Other mechanisms of acquired resistance included mutations in B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase (BRAF) (V600E, 4%), Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Proto-Oncogene (KRAS) (1%) and PIK3CA (E545K; 1%), and oncogenic fusion mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), ret-proto-oncogene (RET) and NTRK (4%) [75]. The resistance mechanisms after frontline osimertinib therapy in 91 patients were analysed through plasma NGS, and as expected, they did not lead to the emergence of T790M mutation. Instead, the most common acquired resistance mechanisms detected were MET amplification (15%), EGFR C797S mutation (7%) and ERBB2, PIK3CA and RAS mutations (2–7%) [80]. Circulating tumour DNA NGS-based genotyping demonstrated an expanding value, capturing the clonal heterogeneity manifested by various resistance mechanisms and overcoming the difficulty in carrying out re-biopsies at progression.

Circulating cell-free tumour DNA for detection of ALK rearrangements and ALK resistance mutations

The detection of an ALK rearrangement can be done in a tissue sample by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH), immunohistochemistry (IHC), retro-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), or integrated into a multiplex test by NGS [81]. EML4-ALK translocation is challenging to detect in cfDNA due to the different possible breakpoints and the number of base pairs involved larger than the typical cfDNA fragments. Options to look for gene translocations are to search for genomic breakpoint junctions or to analyse cell-free RNA[82]. Unlike the analysis of cfDNA to detect mutations, which has already been validated and implemented, plasma RNA analysis is not yet routinely used, despite its feasibility. Technically, RNA isolation and conservation difficulties exceed those in DNA [83], and the sensitivity of RT-PCR is low [84], limiting its use in clinical practice. Other methods under investigation for ALK translocation detection are the CTC and circulating tumour-associated platelets [85]. However, CTC analysis is challenging to implement due to demanding pre-analytical requirements and a lack of clinical validation. Also, RNA released from tumour cells can be transported by vehicles as exosomes to circulant platelets and be extracted from the platelets to be analysed, although this technique is still under investigation [86].

Concerning LB for ALK fusion detection, results are promising. Generally, sensitivity is not as high as for EGFR, but 100% specificity ensures a high predictive positive value. A PCR-based target sequencing showed low sensitivity, 50% with 100% specificity [87]. Instead, with amplicon-based technology, ALK rearrangement detection sensitivity was 78% and 100% for ROS1 [88]. With capture-based next-generation sequencing, sensitivity ranged from 50 to 79% with 100% specificity [61, 89, 90]. The agreement between tissue and plasma NGS for ALK rearrangements was acceptable in different studies, varying from 79.2 to 100% (Table 6).

Despite the good results with ALK inhibitors, resistance is inevitable, where mutations in the ALK gene are one of the resistance mechanisms. ALK mutations are diverse and differ depending on each ALK inhibitor. For example, L1196M often occurs after treatment with crizotinib, G1202R with ceritinib or alectinib, F1174C with ceritinib and I1171T/N/S with alectinib [25]. New generation ALK TKIs, like lorlatinib, ensartinib and entrectinib are potent inhibitors that showed promising results for most resistance mutations [24]. Most studies addressing the resistance to ALK inhibitors have used ctDNA analysis as the dominant tool for detecting mutations and dynamic surveillance [91,92,93]. Dagogo et al. used a 566 hybrid-capture gene assay to perform a longitudinal analysis of plasma specimens from 22 ALK-positive patients with acquired resistance to ALK TKIs. At the disease progression, an ALK fusion and ALK resistance mutations were detected in plasma in 86% and 50% of patients, respectively, with 100% agreement between tissue- and plasma-detected ALK fusions [91]. LB will be essential for selecting and sequencing ALK inhibitors, and in this context, the use of NGS platforms is an asset. As for EGFR progression, non-targeted mechanisms are harder to capture with an LB. MET amplifications can occur in about 15% of patients treated with new-generation TKIs and rarely histological transformation and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition [26, 27]. Thus, it is advisable to pursue a tissue biopsy whenever no resistance mechanism is found in the liquid assay.

The predictive value of cfDNA for selecting patients for ALK TKI treatment was proven in a prospective trial to use blood-based NGS testing to identify actionable genetic alterations and allocate patients to targeted or immunotherapy; among the ALK cohort, ORR was 87.4% with the studied ALK TKI [94]. There is enough evidence for treating patients with an ALK fusion detected on an LB, as supported by the IASCL in the Perspective of the International Society of Liquid Biopsy (ISLB) [95]. However, consistent data correlating plasma findings with clinical outcomes remain scarce, and the standardisation of the methodology is lacking; therefore, clinical application is fragile and more prospective trials are needed.

Circulating cell-free tumour DNA for detection of other oncogenic alterations

Beyond ALK rearrangements, other fusion transcripts from the ROS1, RET or NTRK genes are considered for targeted treatment. For the detection of these alterations, NGS applied to circulating nucleic acids can be helpful. Still, due to the rarity of these subsets, available data is minimal.

ROS1 was punctually detected in studies evaluating NGS for LC genotyping [88, 96], stating that NGS-based assays can detect fusions partners accurately. In the study of Mezquita et al. [97], 67% of ALK and ROS1 fusions were detected in LB specimens at diagnosis with an amplicon-based assay. Dagogo-Jack et al. [98] found that the sensitivity of plasma genotyping for detecting ROS1 fusions was 50% with hybrid-capture plasma NGS. However, in another study (NILE study), only two ROS1 positive patients had paired plasma and tissue samples, and in both, the rearrangement was solely detected in tissue [99]. Data from patients with different drivers progressing on TKIs where the emergence of ROS1 fusions was present, revealed that plasma genotyping allowed to detect the same spectrum of ROS1 fusions and genetic alterations mediating resistance observed in tissue [91]. However, negative results must be interpreted cautiously due to the limited sensitivity and lack of robust data.

RET alterations occur in different cancers, including LC [100]. In a large study involving multiple advanced cancers types, using a hybrid-capture targeted 70-gene cfDNA test, KIF5B-RET fusion was dominant in NSCLC, and that non-KIF5B-RET fusion contributed to anti-EGFR resistance, highlighting the importance of knowing the specific gene partner [101]. RET gatekeeper mutations (e.g. RET V804M and RET S904F) can mediate resistance to multikinase inhibitors [102], and solvent front mutations (e.g. RET G810) were described as a mechanism of resistance to the new selective RET inhibitor, selpercatinib [103]. In the late case, analysis was performed in ctDNA and confirmed in tissue [103]. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group (TR and PM WG) recommendations on the methods to detect RET fusions and mutations for NSCLC advise NGS, and if it is not available, FISH or RT-PCR. Also, consider performing a cell-free nucleic acid NGS broad panel for patients whose tissue is unavailable or exhausted. Tumour testing is still required if a RET alteration is not detected in a LB [104].

NTRK 1, NTRK 2 and NTRK 3 fusions encode NTRK fusion oncogenic proteins involved in multiple infantile and adult cancers and are biomarkers for the use of TRK small molecule inhibitors [105]. NTRK fusion gene can be detected by IHQ, FISH, RT-PCR, and both RNA-based and DNA-based NGS. NGS platforms should include all fusions variants, including NTRK2 and 3 that present large intronic regions. Also, targeted-RNA platforms are helpful for this kind of detection. The ESMO TR and PM WG evaluated the available methods used to detect these tumour-agnostic alterations for daily practice and clinical research in different scenarios [106]. In the scenario of testing an unselected population where NTRK1/2/3 fusions are uncommon, as it is in LC, either frontline sequencing (preferentially RNA-sequencing) or screening by IHQ followed by sequencing of positive cases is advised [106]. NTRK fusions and resistance mutations detection in cfDNA is feasible [107], awaiting further experience.

LB was used to detect the MET exon 14 skipping mutation in a clinical trial, the phase II VISION study, in which 66 out of 99 patients who entered the study were included based on the detection in the plasma and derived the same benefit as those detected on tissue [108]. Thus, and considering that all these events are rare in LC, ideally, the detection should be part of a strategy that allows the simultaneous screening of multiple targetable alterations. The contribution of cfDNA genotyping in this strategy will be clarified below.

Liquid biopsy cfDNA NGS for genotyping untreated advanced lung cancer

In LC patients with advanced disease, identifying potentially treatable tumour genomic changes is a key element. Considering the current target drugs availability and current evidence, ESMO recommends routine use of NGS on tumour samples in advanced NSCLC, including ALK, BRAF, EGFR, ERBB2, KRAS, MET, NTRK, RET and ROS1 genes [109, 110]. The panel may need to be expanded depending on the clinical or investigational setting [110].

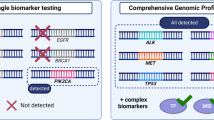

Undoubtedly the sequential analysis, gene by gene, is impractical in the real-world setting, indicating the need for multiplex sequencing [111]. NGS is based on the massive and parallel sequencing of millions of different DNA molecules, allowing the detection of several mutations in multiple genes [112]. Initially used in tumour samples, as the sensitivity improved, it became possible to be applied to LB, with new platforms able to detect tiny fractions of tumour DNA in circulation. Unlike conventional plasma genotyping techniques, such as the Cobas test, or digital PCR, which detect specific mutations of a given probe, NGS techniques have the potential to genotype tumours more comprehensively [113]. Generally, NGS techniques can be amplicon-based or hybrid-capture based, accounting for differences in test performance and range of alterations detected [113].

For LC genotyping, cfDNA test performance depends on the technology used, with overall sensitivity around 70–81% and very high specificity, as proved in different studies (Table 7).

The BioCAST/IFCT-1002 was a pilot trial from Conraud and colleagues where a technology based on multiplex PCR covering 12 specific genomic regions covering the most relevant genes was used. Test's sensitivity was 58% and specificity 87% having tumour samples as reference [114]. In the work of Thompson et al., NGS-based LB found genomic changes in 84% of patients, 50 considered "drivers", 12 resistance and 22 additional changes in genes for which there were experimental therapies or clinical trials [115]. In untreated NSCLC patients with no tissue sample available, plasma NGS detected clinically relevant molecular changes in 23% [116], being extremely useful in that context. Our group used a DNA amplicon-based assay in a cohort of 115 Portuguese treatment-naive patients with paired tissue samples, attaining 81.0% sensitivity, 95% specificity, 95% PPV, 84% NPV, 88% and 76% concordance [46].

To improve gene fusions detection, Papadopoulou et al. used an amplicon-based NGS combined panel for cfDNA and cfRNA for the initial molecular characterisation of 121 NSCLC patients. The panel included 12 genes frequently altered in NSCLC and fusions in ALK, ROS1 and RET genes. At least one mutation was found in 49% of patients, including one EML4-ALK translocation. Among the 36 patients with tissue paired samples, concordance was high (77 to 83%). Using ultra-deep NGS technology and filtering the clonal hematopoietic somatic mutations, the detection of de novo known oncogenic drivers with a hybrid capture panel covering 37 LC-related genes led to a sensitivity of 75% with 100% specificity [117]. Plagnol et al. validated an enhanced tagged amplicon sequencing (eTAm-Seq™) technology to profile 36 genes commonly mutated in NSCLC for actionable genomic alterations in cell-free DNA, including point mutations, indels, amplifications and fusions. This assay allowed the detection of ALK and ROS1 gene fusions and DNA amplifications in ERBB2, FGFR1, MET and EGFR with high sensitivity and specificity [118]. Also, a large assay for initial genomic profiling studied ctDNA from 1552 patients with NSCLC with a hybrid capture-based of 62 genes. At least one genomic alteration was detected in 86% of cases, among which 32% was a targetable alteration according to NCCN guidelines. Also, kinases fusions were detected in 5% of cases in ALK, RET, ROS1, FGFR3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene (PDGFRA), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta gene (PDGFRB). Furthermore, exon 14 MET skipping mutation was present in 1.9% of cases [119].

The clinical relevance of integrating cfDNA genotyping in metastatic NSCLC clinical management has progressively been proven. Leigh et al. conducted a large prospective trial, Non-invasive versus Invasive Lung Evaluation (NILE) [99], to demonstrate that a comprehensive cfDNA test used at diagnosis of metastatic NSCLC is non-inferior to that of physician discretion standard of care tissue genotyping to identify guideline-recommended genomic biomarkers. The authors found 80% cfDNA sensitivity for any guideline-recommended biomarker, including EGFR mutations, ALK fusions, ROS1 fusions, BRAF V600E mutation, RET fusions, MET amplification and MET exon 14 skipping variants, and ERBB2 mutations. For FDA-approved targets (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF), the concordance was 98.2%, with 100% positive predictive value for cfDNA versus tissue. Also, when using cfDNA in addition to tissue, the detection increased by 48%, including in patients with negative, not assessed, or insufficient tissue results. The median turn-around time for cfDNA was significantly faster than that of tissue (9 vs 15 days; P < 0.0001) [99]. In another crucial study, from a “real-world” clinical setting, Aggarwal et al. demonstrated that the integration of plasma NGS testing into the routine management of stage IV NSCLC increased the detection of therapeutically targetable mutations [120]. Recently, in one of the most extensive studies with ctDNA on 8388 advanced NSCLC patients, activating alterations in actionable oncogenes were identified in 48% of patients, including EGFR (26.4%), MET (6.1%), and BRAF (2.8%) alterations and fusions (ALK, RET, and ROS1) in 2.3% [121].

These studies confirm that a cfDNA comprehensive analysis is powerful to detect targetable genomic alterations in untreated NSCLC patients. At present, blood-based genomic profiling-based clinical trials are being conducted. More results from the BFAST, phase II/III global, multi-cohort study evaluating blood-based NGS detection of actionable genetic alterations in ctDNA for selecting patients for 1st line targeted therapies/immunotherapy will elucidate the predictive value of LB, as already stated for ALK [94]. Both the Guardant360 CDx® assay (Guardant Health, Redwood City, CA) [122] and the Foundation One Liquid CDx® test (Foundation Medicine, Inc.) are approved for multiple biomarkers detection in cfDNA isolated from plasma specimens [123] (Table 5). Other platforms are under investigation and approval process.

Clinical value of liquid biopsy for monitoring treatment response and progression

Currently, tumour response evaluation is based on radiology RECIST criteria [124] and complemented with functional images. This evaluation represents an isolated timepoint, dependent on the exam resolution and exposing patients to radiation. At progression, tumours had been suffering from temporal and therapeutic selective pressure and cancer heterogeneity [31], and clonal divergence from the primary tumour emerges as an obstacle to be overcome and thus needs to be considered in subsequent therapeutic options [125]. As a potential representative of all shedding tumour focus with each clonal expression, LB is a potential tool to face this challenge. Molecular disease monitoring has three significant purposes: monitoring disease burden as an indicator of tumour response or relapse, monitoring clonal evolution by analysing variations of the variant allelic fractions and detecting the emergence of resistance mechanisms.

One of the first studies approaching response through LB was the FASTACT-2 trial, chemotherapy interspersed with erlotinib. Blood persistence of EGFR mutation after an 8-week treatment was linked to a poor prognosis [125]. The PFS was lower in patients who maintained detectable levels of EGFR mutation in plasma after 2-month treatment, 6.3 vs 10.1 months [126]. Also, as with 1st line EGFR TKI treatment, early disappearance, within 6 weeks, of the T790M mutation was associated with better clinical outcomes with osimertinib treatment [127]. Serial ctDNA analysis can detect the appearance of T790M before radiological progression defined by the RECIST criteria. Zheng and colleagues detected the T790M mutation at the median of 2.2 months before radiological progression [57]. The mutation was present before radiological progression in another series as early as 344 days [128]. Likewise, after 3rd generation TKI treatment, changes in plasma T790M levels were detected, in most cases mirroring the clinical and radiological evolution [129]. Among our patients submitted to ctDNA longitudinal monitoring, a decrease in variant allelic frequency (VAF) or clearance of mutant alleles was associated with response, while an increase or emergence of novel alterations was linked to progression. In most cases, such variations anticipated radiographic changes, with a median time of 0.86 months [47].

Clonal monitoring has been integrated into recent trials involving new generation ALK inhibitors. For example, Dagogo et al. demonstrated with serial plasma sampling that ALK mutations emerged and disappeared during treatment with sequential ALK TKIs, and that such data was helpful to guide TKIs selection [91]. Also, Shaw et al. studied the efficacy of lorlatinib among patients with and without ALK mutations using plasma or tissue genotyping [130]. For plasma genotyping, PFS did not differ significantly in patients with and without ALK mutations [130], meaning that plasma negative patients include true negative cases and some false negatives that are positive on tissue. Therefore, like in the EGFR T790M context, tissue confirmation must be pursued whenever possible in case of a negative plasma result.

These findings reinforce the need to monitor the disease in a model that integrates clinical progression assessed by symptoms, radiological (RECIST) and clonal finding through monitoring the ctDNA. Nevertheless, from a clinical point of view, the most pertinent question is whether early detection, prior to radiological, and the consequent anticipation of therapeutic change will translate into more favourable clinical outcomes. To date, there is no data available supporting this hypothesis. The results from The AZD9291 (Osimertinib) Treatment on Positive Plasma T790M in EGFR-mutant NSCLC Patients (APPLE Trial) as well as of similar studies are expected to confirm the value of LB for the decision-making process [131].

Liquid biopsies pitfalls

Considering the increasing accuracy and the conquered role in guiding clinical decisions, adopting LB in LC management, specifically cfDNA analysis, is inevitable. Still, it is indispensable to understand the LB limitations and drawbacks. First of all, there is some discrepancy between cfDNA results and paired tissue samples relating to the reduced sensitivity of cfDNA responsible for false negatives. Cell-free DNA analysis is technically demanding, requiring rigorous standardised protocols for plasma collection preservation, DNA isolation, library preparation and sequencing, being susceptible to failures in those multiple pre-analytical steps [41, 45, 132]. Regarding sequencing analytics, understanding the accuracy of the test and the range of hotspots covered is essential and is a new requirement for the clinician. As an example, not all assays can detect gene amplifications and rearrangements, requiring appropriate technologies, as elucidated before. Also, accurate post-analytical procedures are needed to avoid misinterpretations. In this sense, expertise in bioinformatics is paramount in interpreting findings, distinguishing germline alterations and clonal haematopoiesis-related alterations from oncogenic tumour mutations, and avoiding false-positive results [42, 45, 132]. Detected variants must be reported according to the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and College of American Pathologists [133].

The intrinsic nature of the disease can compromise LB results. Some tumours release low or no DNA to the circulation (non-shedders) [134]. The amount of ctDNA is related to the disease stage, tumour burden, localisation, and size of the metastasis, particularly limited in less extensive, oligometastatic disease and exclusively brain metastization [46, 135, 136]. Also, cfDNA profiling does not allow the morphologic characterisation of the tumour, PDL1 IHQ assessment, and rule out histological transformation.

Thus, considering the clinical context and the exposed limitations, a proper interpretation requires collaborative efforts between clinicians, pathologists and molecular biologists gathered in a Mutational Tumour Board to optimise treatment personalisation and contribute to accurate precision medicine.

Interpretation of liquid biopsy results

The predictive value of ctDNA findings supports LB reliability for clinical decisions. As exposed above, ctDNA genotyping revealed extremely high analytic specificity and positive predictive value, making false positives improbable. In addition, identifying oncogenic mutations through the ctDNA analysis predicts the clinical response in a similar magnitude of tumour detection. Therefore, if a mutation is detected, it is probably a true positive result and identifies candidates for treatment. However, due to the low sensitivity, a negative test does not exclude the presence of a mutation and results must be designated as uninformative or alteration(s) not detected. It is advised confirmation through tissue biopsy.

On the opposite, but less frequent, is detecting oncogenic alterations in plasma not present in the tissue, which can be considered a false positive if tissue is the reference. This can occur due to tumour heterogeneity, with some alterations not being expressed in the correspondent sample, especially concerning progression, where “de novo” alterations are expected to occur. It is not a handicap of LB but an advantageous, expressing the complementary role to tissue analysis. Genuine false positives are rare and can be associated with analytic or interpretation errors, different tumour origin or clonal haematopoiesis [95]. In the last case, germline cell sequencing can help exclude this.

Considering the EGFR mutated scenario as the paradigmatic example, LB is the first test to look for the T790M mutation, as recommended [4]. If the resistance mutation is found in plasma (positive test), the patient is eligible for treatment with a 3rd generation inhibitor. On the other hand, a tissue biopsy is advised when the T790M mutation is not detected. The absence of plasma mutation (negative test) may occur because the resistance mechanism is another, due to a false-negative attributed to the test's low sensitivity or the absence of "secretion" for the circulation of DNA through the tumour. In the latter case, the initial driver mutation will also not be present. In cases where it is not possible to perform a tissue biopsy, the LB can be repeated, and as the tumour or its metastases growths, it may "release" more ctDNA, allowing to detect the T790M. Depending on the context, other alternatives to plasma ctDNA may be other biological fluids, like CSF [136]. The same rationale for interpretation applies to the other oncogenic alterations found with a plasma assay, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithm for clinical interpretation of a liquid biopsy for the detection of targetable mutations. For clinical interpretation, a targetable alteration found in a liquid biopsy is considered a true positive finding and is used to guide treatment selection. A liquid biopsy with no detectable alteration must be confirmed with a tissue biopsy to overcome false negative results

Future perspectives

LB conquered a definitive place in the management of patients with advanced or metastatic LC. Future perspectives will embrace expanding its application to immunotherapy and less advanced stages of the disease.

Concerning NSCLC advanced disease, targeted treatments produce remarkably high and sustained response rates, contributing to the incremental survival observed in the last decade in NSCLC patients [137] and must be the first treatment option. The following options are immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors alone or combined with chemotherapy [3, 4]. The only validated predictive factor for selecting patients for immune checkpoint inhibition is tissue expression of PD-L1[4], which has numerous limitations that are beyond the scope of this review. Other biomarkers have been explored, namely Tumour Mutation Burden (TMB)[138]. Briefly, TMB refers to the number of nonsynonymous mutations per megabase. Hypothetically, a high TMB correlates with patients' responses to treatment with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [130]. Blood TMB (bTMB) has been investigated in clinical trials with different plasma-based NGS platforms. For example, in patients treated with atezolizumab, a high bTMB (> 16 SNVs, detected among 394 genes) correlated with the response with the FoundationOne CDx NGS assay [139], pointing to blood TMB as a surrogate of tissue TMB. However, there is controversy regarding concordance between tissue TMB and cfDNA TMB, particularly when different assays are compared [140]. Therefore, adopting blood TMB requires additional validation and harmonisation of the technical aspects [140]. In addition, other specific mutations, such as KRAS, TP53, STK11 and PTEN have been described as influencing the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and can be detected and tracked in the blood [141, 142]. Future perspectives shall explore the role of LB in patient selection, response evaluation, disease monitoring and interpretation of pseudo-progressive disease. Clinical trials embracing genomics with immunotherapy must be held.

Moving to the role of LB in localized disease, the detection and molecular characterisation of minimal residual disease (MRD) is of particular importance. MRD evaluation can improve patient selection for adjuvant therapy, contributing to clinical outcomes while avoiding overtreatments [44]. Several studies have suggested that ctDNA can be used to detect the presence of MRD after surgical resection in several cancer types, including LC, by documenting a marked decline in presurgical and postsurgical levels of ctDNA [143, 144]. Additional data in support of using ctDNA-based MRD detection was obtained from the TRACERx trial [145]. This study created an individualized panel of single-nucleotide variants for each patient using exome sequencing of their primary tumour. The results demonstrated that ctDNA status was closely linked to disease relapse after intent-to-cure surgery [145]. Subsequently, another study reported the application of CAPP-Seq to assess for MRD. Detectable ctDNA was found in 72% of all patients who exhibited radiographic progression and preceded these findings by a median of 5.2 months. The results of these studies together imply a robust potential role of ctDNA-assessed MRD [146] that must be further explored. Promising results of the application of cfDNA to early cancer detection are ongoing and technical advances are expected to overcome the sensitivity and specificity limitations inherent to the study of an asymptomatic and low burden disease population. Furthermore, ctDNA epigenetic markers in plasma can be detected early during cancer pathogenesis and provide information on early detection, prognosis, MRD, and therapy response and will open a new era in the LB field [147]. Finally, incorporating ctDNA in clinical trial design in the different scenarios of LC management is becoming indispensable and must be accomplished.

Integrating cfDNA comprehensive genomic tumour profile in lung cancer management

Integrating a comprehensive genomic tumour profile will be the cornerstone for LC management, and cfDNA will be an indispensable tool, as proposed in Fig. 2. Circulating-tumour DNA genotyping is, at least, complementary to tissue genotyping, with the potential of having a better cost/efficacy profile with a shorter turn-around time [99]. Head-to-head comparison of a liquid-first versus tissue-first genotyping strategy, using the same NGS platform, with a comprehensive analysis of costs and associated health resources expenditure is eagerly needed. For detection of resistance mechanisms, evidence corroborates LB as the first step test, with tissue biopsy as a backup for negative results.

Conclusion

The therapeutic decision in advanced LC stages is complex, involving several parameters. Clinical and functional evaluation of the patient condition and disease extension, combined with tumour morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular characterization, is paramount for clinical decision. As the disease progresses, all those factors are susceptible to changes, including the emergence of resistance mechanisms. Through ctDNA genomic profiling, a LB will more likely be the choice to identify genomic alterations in untreated patients and monitor and detect resistance mechanisms, as it embraces tumour heterogeneity, is non-invasive and repeatable. The LB will have a promissory impact on LC patients' survival and quality of life.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin n/a(n/a).

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30.

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2021: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19(3):254–66.

Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv192–237.

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–39.

Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(5):339–46.

Aguiar F, Fernandes G, Queiroga H, Machado JC, Cirnes L, Souto Moura C, et al. Overall survival analysis and characterization of an EGFR Mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) population. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(1):10–7.

Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, Yang C-H, Chu D-T, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–57.

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–46.

Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3327–34.

Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–25.

Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):2240–7.

Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Sima CS, Riely GJ, Chmielecki J, Kris MG, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant lung cancer: distinct natural history of patients with tumors harboring the T790M mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1616–22.

Sun JM, Ahn MJ, Choi YL, Ahn JS, Park K. Clinical implications of T790M mutation in patients with acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2013;82(2):294–8.

Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, Wong KK, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(6):2070–5.

Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1046–61.

Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M–positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;376(7):629–40.

Minari R, Bordi P, Tiseo M. Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer: review on emerged mechanisms of resistance. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(6):695–708.

Lazzari C, Gregorc V, Karachaliou N, Rosell R, Santarpia M. Mechanisms of resistance to osimertinib. J Throac Dis. 2019;12(5):2851–8.

Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P, Giovannetti E, Tiseo M. Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(9):725–37.

Chia PL, Mitchell P, Dobrovic A, John T. Prevalence and natural history of ALK positive non-small-cell lung cancer and the clinical impact of targeted therapy with ALK inhibitors. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:423–32.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4–ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–6.

Duruisseaux M, Besse B, Cadranel J, Pérol M, Mennecier B, Bigay-Game L, et al. Overall survival with crizotinib and next-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (IFCT-1302 CLINALK): a French nationwide cohort retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21903–17.

Caccese M, Ferrara R, Pilotto S, Carbognin L, Grizzi G, Caliò A, et al. Current and developing therapies for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with ALK abnormalities: update and perspectives for clinical practice. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(17):2253–66.

Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Katayama R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(10):1118–33.

Takegawa N, Hayashi H, Iizuka N, Takahama T, Ueda H, Tanaka K, et al. Transformation of ALK rearrangement-positive adenocarcinoma to small-cell lung cancer in association with acquired resistance to alectinib. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):953–5.

Fukuda K, Takeuchi S, Arai S, Katayama R, Nanjo S, Tanimoto A, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a mechanism of ALK inhibitor resistance in lung cancer independent of ALK mutation status. Can Res. 2019;79(7):1658–70.

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS pG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371–81.

Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, Arcila ME, Beasley MB, Bernicker EH, et al. Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(3):321–46.

Vanderlaan PA, Yamaguchi N, Folch E, Boucher DH, Kent MS, Gangadharan SP, et al. Success and failure rates of tumor genotyping techniques in routine pathological samples with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(1):39–44.

de Bruin EC, McGranahan N, Mitter R, Salm M, Wedge DC, Yates L, et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science. 2014;346(6206):251–6.

Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(9):531–48.

Wu J, Hu S, Zhang L, Xin J, Sun C, Wang L, et al. Tumor circulome in the liquid biopsies for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Theranostics. 2020;10(10):4544–56.

GJG S, Wurdinger T. Tumor-educated platelets. Blood. 2019;133(22):2359–64.

Junqueira-Neto S, Batista IA, Costa JL, Melo SA. Liquid biopsy beyond circulating tumor cells and cell-free DNA. Acta Cytol. 2019;63(6):479–88.

Rijavec E, Coco S, Genova C, Rossi G, Longo L, Grossi F. Liquid biopsy in non-small cell lung cancer: highlights and challenges. Cancers. 2020;12(1):17.

Stroun M, Anker P, Maurice P, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Beljanski M. Neoplastic characteristics of the DNA found in the plasma of cancer patients. Oncology. 1989;46(5):318–22.

Jahr S, Hentze H, Englisch S, Hardt D, Fackelmayer FO, Hesch RD, et al. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1659–65.

Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(4):223–38.

Diaz LA Jr, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):579–86.

Meddeb R, Pisareva E, Thierry AR. Guidelines for the preanalytical conditions for analyzing circulating cell-free DNA. Clin Chem. 2019;65(5):623–33.

Rolfo C, Mack PC, Scagliotti GV, Baas P, Barlesi F, Bivona TG, et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a statement paper from the IASLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(9):1248–68.

Pisapia P, Malapelle U, Troncone G. Liquid biopsy and lung cancer. Acta Cytol. 2019;63(6):489–96.

Pellini B, Szymanski J, Chin RI, Jones PA, Chaudhuri AA. Liquid biopsies using circulating tumor DNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Surg Clin. 2020;30(2):165–77.

Rolfo C, Mack PC, Scagliotti GV, Baas P, Barlesi F, Bivona TG, et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a statement paper from the IASLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(9):1248–68.

Fernandes MGO, Cruz-Martins N, Souto Moura C, Guimarães S, Pereira Reis J, Justino A, et al. Clinical application of next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA for genotyping untreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(11):2707.

Fernandes MGO, Sousa C, Pereira Reis J, Cruz-Martins N, Souto Moura C, Guimarães S, et al. Liquid biopsy for disease monitoring in non-small cell lung cancer: the link between biology and the clinic. Cells. 2021;10(8):1912.

Qian X, Liu J, Sun Y, Wang M, Lei H, Luo G, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA has a high degree of specificity to detect exon 19 deletions and the single-point substitution mutation L858R in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(20):29154–65.

Luo J, Shen L, Zheng D. Diagnostic value of circulating free DNA for the detection of EGFR mutation status in NSCLC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6269.

Qiu M, Wang J, Xu Y, Ding X, Li M, Jiang F, et al. Circulating tumor DNA is effective for the detection of EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(1):206–12.

Mao C, Yuan JQ, Yang ZY, Fu XH, Wu XY, Tang JL. Blood as a substitute for tumor tissue in detecting EGFR mutations for guiding EGFR TKIs treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(21):e775.

Zhou S, Huang R, Cao Y. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in peripheral blood circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. 2020;99(40):e21965.

Passiglia F, Rizzo S, Di Maio M, Galvano A, Badalamenti G, Listì A, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of circulating tumor DNA for the detection of EGFR-T790M mutation in NSCLC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13379.

Reck M, Hagiwara K, Han B, Tjulandin S, Grohé C, Yokoi T, et al. ctDNA determination of EGFR mutation status in European and Japanese patients with advanced NSCLC: the ASSESS study. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1682–9.

Han B, Tjulandin S, Hagiwara K, Normanno N, Wulandari L, Laktionov K, et al. EGFR mutation prevalence in Asia-Pacific and Russian patients with advanced NSCLC of adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma histology: The IGNITE study. Lung Cancer. 2017;113:37–44.

Sacher AG, Paweletz C, Dahlberg SE, Alden RS, O’Connell A, Feeney N, et al. Prospective validation of rapid plasma genotyping for the detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations in advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(8):1014–22.

Zheng D, Ye X, Zhang MZ, Sun Y, Wang JY, Ni J, et al. Plasma EGFR T790M ctDNA status is associated with clinical outcome in advanced NSCLC patients with acquired EGFR-TKI resistance. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):20913.

Kukita Y, Uchida J, Oba S, Nishino K, Kumagai T, Taniguchi K, et al. Quantitative identification of mutant alleles derived from lung cancer in plasma cell-free DNA via anomaly detection using deep sequencing data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e81468.

Reckamp KL, Melnikova VO, Karlovich C, Sequist LV, Camidge DR, Wakelee H, et al. A highly sensitive and quantitative test platform for detection of NSCLC EGFR mutations in urine and plasma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1690–700.

Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Han JY, Ahn MJ, Ramalingam SS, Delmonte A, Hsia TC, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation analysis in tissue and plasma from the AURA3 trial: osimertinib versus platinum-pemetrexed for T790M mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(2):373–80.

Schwartzberg LS, Horinouchi H, Chan D, Chernilo S, Tsai ML, Isla D, et al. Liquid biopsy mutation panel for non-small cell lung cancer: analytical validation and clinical concordance. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2020;4(1):15.

Kimura H, Suminoe M, Kasahara K, Sone T, Araya T, Tamori S, et al. Evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in serum DNA as a predictor of response to gefitinib (IRESSA). Br J Cancer. 2007;97(6):778–84.

Goto K, Ichinose Y, Ohe Y, Yamamoto N, Negoro S, Nishio K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in circulating free DNA in serum: from IPASS, a phase III study of gefitinib or carboplatin/paclitaxel in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(1):115–21.

Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M, Ciuleanu T, Cole R, McWalter G, et al. Gefitinib treatment in EGFR mutated caucasian NSCLC: circulating-free tumor DNA as a surrogate for determination of EGFR status. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(9):1345–53.

Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M, Ciuleanu T, McCormack R, Webster A, et al. First-line gefitinib in Caucasian EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients: a phase-IV, open-label, single-arm study. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(1):55–62.

Karachaliou N, Mayo-de las Casas C, Queralt C, de Aguirre I, Melloni B, Cardenal F, et al. Association of EGFR L858R mutation in circulating free DNA with survival in the EURTAC trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(2):149–57.

fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-blood-test-detect-gene-mutation-associated-non-small-cell-lung-cancer.

Goss G, Tsai CM, Shepherd FA, Bazhenova L, Lee JS, Chang GC, et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1643–52.

Hasegawa T, Sawa T, Futamura Y, Horiba A, Ishiguro T, Marui T, et al. Feasibility of rebiopsy in non-small cell lung cancer treated with epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Intern Med. 2015;54(16):1977–80.

Uozu S, Imaizumi K, Yamaguchi T, Goto Y, Kawada K, Minezawa T, et al. Feasibility of tissue re-biopsy in non-small cell lung cancers resistant to previous epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):175.

Kawamura T, Kenmotsu H, Taira T, Omori S, Nakashima K, Wakuda K, et al. Rebiopsy for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(7):1001–5.

Chouaid C, Dujon C, Do P, Monnet I, Madroszyk A, Le Caer H, et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of re-biopsy in advanced non small-cell lung cancer: a prospective multicenter study in a real-world setting (GFPC study 12–01). Lung Cancer. 2014;86(2):170–3.

Karlovich C, Goldman JW, Sun JM, Mann E, Sequist LV, Konopa K, et al. Assessment of EGFR mutation status in matched plasma and tumor tissue of NSCLC patients from a phase I study of rociletinib (CO-1686). Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(10):2386–95.

Jenkins S, Yang JC, Ramalingam SS, Yu K, Patel S, Weston S, et al. Plasma ctDNA analysis for detection of the EGFR T790M mutation in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(7):1061–70.

Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Wu YL, Han JY, Ahn MJ, Ramalingam SS, John T, et al. Analysis of resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR T790M advanced NSCLC from the AURA3 study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:Viii741.

Oxnard GR, Thress KS, Alden RS, Lawrance R, Paweletz CP, Cantarini M, et al. Association between plasma genotyping and outcomes of treatment with osimertinib (AZD9291) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(28):3375–82.

Gray JE, Okamoto I, Sriuranpong V, Vansteenkiste J, Imamura F, Lee JS, et al. Tissue and plasma EGFR mutation analysis in the FLAURA trial: osimertinib versus comparator EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor as first-line treatment in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(22):6644–52.

European Medicines Agency. Iressa: public assessment report—product information. 2016.

Ramalingam SS, Cheng Y, Zhou C, Ohe Y, Imamura F, Cho BC, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib: Preliminary data from the phase III FLAURA study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:viii740.

Hofman P. Detecting resistance to therapeutic ALK inhibitors in tumor tissue and liquid biopsy markers: an update to a clinical routine practice. Cells. 2021;10(1):168.

Bruno R, Fontanini G. Next generation sequencing for gene fusion analysis in lung cancer: a literature review. Diagnostics. 2020;10(8):521.

Aguado C, Giménez-Capitán A, Karachaliou N, Pérez-Rosado A, Viteri S, Morales-Espinosa D, et al. Fusion gene and splice variant analyses in liquid biopsies of lung cancer patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(5):525–31.

Park C-K, Kim J-E, Kim M-S, Kho B-G, Park H-Y, Kim T-O, et al. Feasibility of liquid biopsy using plasma and platelets for detection of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(8):2071–82.

Provencio M, Pérez-Callejo D, Torrente M, Martin P, Calvo V, Gutiérrez L, et al. Concordance between circulating tumor cells and clinical status during follow-up in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):59408–16.

Liu L, Lin F, Ma X, Chen Z, Yu J. Tumor-educated platelet as liquid biopsy in lung cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;146:102863.

Kunimasa K, Kato K, Imamura F, Kukita Y. Quantitative detection of ALK fusion breakpoints in plasma cell-free DNA from patients with non-small cell lung cancer using PCR-based target sequencing with a tiling primer set and two-step mapping/alignment. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222233.

Mezquita L, Hu Y, Howarth K, Jovelet C, Planchard D, Lacroix L, et al. Abstract 4581: Feasibility of an amplicon-based liquid biopsy for ALK and ROS1 fusions in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Cancer Res. 2018;78(13 supplement):4581.

Cui S, Zhang W, Xiong L, Pan F, Niu Y, Chu T, et al. Use of capture-based next-generation sequencing to detect ALK fusion in plasma cell-free DNA of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):2771–80.

Wang Y, Tian P-W, Wang W-Y, Wang K, Zhang Z, Chen B-J, et al. Noninvasive genotyping and monitoring of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearranged non-small cell lung cancer by capture-based next-generation sequencing. Oncotarget. 2016;7(40):65208–17.

Dagogo-Jack I, Brannon AR, Ferris LA, Campbell CD, Lin JJ, Schultz KR, et al. Tracking the evolution of resistance to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors through longitudinal analysis of circulating tumor DNA. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–14.

Horn L, Whisenant JG, Wakelee H, Reckamp KL, Qiao H, Leal TA, et al. Monitoring therapeutic response and resistance: analysis of circulating tumor DNA in patients with ALK+ lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(11):1901–11.

Shaw AT, Martini J-F, Besse B, Bauer TM, Lin C-C, Soo RA, et al. Early circulating tumor (ct)DNA dynamics and efficacy of lorlatinib in patients (pts) with advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):9019.

Gadgeel SM, Mok TSK, Peters S, Alexander JAA, Leighl NB, Sriuranpong V, et al. Phase II/III blood first assay screening trial (BFAST) in patients (pts) with treatment-naïve NSCLC: Initial results from the ALK+ cohort. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:918.

Rolfo C, Cardona AF, Cristofanilli M, Paz-Ares L, Diaz Mochon JJ, Duran I, et al. Challenges and opportunities of cfDNA analysis implementation in clinical practice: perspective of the International Society of Liquid Biopsy (ISLB). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;151:102978.

Guibert N, Hu Y, Feeney N, Kuang Y, Plagnol V, Jones G, et al. Amplicon-based next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA for detection of driver and resistance mutations in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(4):1049–55.

Mezquita L, Swalduz A, Jovelet C, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Howarth K, Planchard D, et al. Clinical relevance of an amplicon-based liquid biopsy for detecting ALK and ROS1 fusion and resistance mutations in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:272–82.

Dagogo-Jack I, Rooney M, Nagy RJ, Lin JJ, Chin E, Ferris LA, et al. Molecular analysis of plasma from patients with ROS1-positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(5):816–24.

Leighl NB, Page RD, Raymond VM, Daniel DB, Divers SG, Reckamp KL, et al. Clinical utility of comprehensive cell-free DNA analysis to identify genomic biomarkers in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(15):4691–700.

Kato S, Subbiah V, Marchlik E, Elkin SK, Carter JL, Kurzrock R. RET aberrations in diverse cancers: next-generation sequencing of 4871 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(8):1988–97.

Rich TA, Reckamp KL, Chae YK, Doebele RC, Iams WT, Oh M, et al. Analysis of cell-free DNA from 32,989 advanced cancers reveals novel co-occurring activating RET alterations and oncogenic signaling pathway aberrations. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(19):5832–42.

Wirth LJ, Kohno T, Udagawa H, Matsumoto S, Ishii G, Ebata K, et al. Emergence and targeting of acquired and hereditary resistance to multikinase RET inhibition in patients with RET-altered cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–7.

Solomon BJ, Tan L, Lin JJ, Wong SQ, Hollizeck S, Ebata K, et al. RET solvent front mutations mediate acquired resistance to selective RET inhibition in RET-driven malignancies. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(4):541–9.

Belli C, Penault-Llorca F, Ladanyi M, Normanno N, Scoazec JY, Lacroix L, et al. ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect RET fusions and mutations in daily practice and clinical research. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):337–50.

Amatu A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S. NTRK gene fusions as novel targets of cancer therapy across multiple tumour types. ESMO Open. 2016;1(2):e000023.

Marchiò C, Scaltriti M, Ladanyi M, Iafrate AJ, Bibeau F, Dietel M, et al. ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect NTRK fusions in daily practice and clinical research. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(9):1417–27.

Russo M, Misale S, Wei G, Siravegna G, Crisafulli G, Lazzari L, et al. Acquired resistance to the TRK inhibitor entrectinib in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(1):36–44.

Paik PK, Felip E, Veillon R, Sakai H, Cortot AB, Garassino MC, et al. Tepotinib in non–small-cell lung cancer with MET Exon 14 skipping mutations. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):931–43.

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2021: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(3):254–66.

Mosele F, Remon J, Mateo J, Westphalen CB, Barlesi F, Lolkema MP, et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(11):1491–505.

Fernandes MGO, Jacob M, Martins N, Moura CS, Guimaraes S, Reis JP, et al. Targeted gene next-generation sequencing panel in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: paving the way for clinical implementation. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(9):1229.

Reuter JA, Spacek DV, Snyder MP. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol Cell. 2015;58(4):586–97.

Gray PN, Dunlop CLM, Elliott AM. Not all next generation sequencing diagnostics are created equal: understanding the nuances of solid tumor assay design for somatic mutation detection. Cancers. 2015;7(3):1313–32.

Couraud S, Vaca-Paniagua F, Villar S, Oliver J, Schuster T, Blanché H, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of actionable mutations by deep sequencing of circulating free DNA in lung cancer from never-smokers: a proof-of-concept study from BioCAST/IFCT-1002. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(17):4613–24.

Thompson JC, Yee SS, Troxel AB, Savitch SL, Fan R, Balli D, et al. Detection of therapeutically targetable driver and resistance mutations in lung cancer patients by next-generation sequencing of cell-free circulating tumor DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(23):5772–82.

Besse B, Remon J, Lacroix L, Mezquita L, Jovelet C, Howarth K, et al. Evaluation of liquid biopsies for molecular profiling in untreated patients with stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):11540.

Li BT, Janku F, Jung B, Hou C, Madwani K, Alden R, et al. Ultra-deep next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with advanced lung cancers: results from the Actionable Genome Consortium. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(4):597–603.

Plagnol V, Woodhouse S, Howarth K, Lensing S, Smith M, Epstein M, et al. Analytical validation of a next generation sequencing liquid biopsy assay for high sensitivity broad molecular profiling. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193802.

Schrock AB, Welsh A, Chung JH, Pavlick D, Bernicker EH, Creelan BC, et al. Hybrid capture–based genomic profiling of circulating tumor DNA from patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(2):255–64.

Aggarwal C, Thompson JC, Black TA, Katz SI, Fan R, Yee SS, et al. Clinical implications of plasma-based genotyping with the delivery of personalized therapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(2):173–80.

Mack PC, Banks KC, Espenschied CR, Burich RA, Zill OA, Lee CE, et al. Spectrum of driver mutations and clinical impact of circulating tumor DNA analysis in non–small cell lung cancer: analysis of over 8000 cases. Cancer. 2020;126(14):3219–28.

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P200016.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47.

Mok T, Wu YL, Lee JS, Yu CJ, Sriuranpong V, Sandoval-Tan J, et al. Detection and dynamic changes of EGFR mutations from circulating tumor DNA as a predictor of survival outcomes in NSCLC patients treated with first-line intercalated erlotinib and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(14):3196–203.

Lee JY, Qing X, Xiumin W, Yali B, Chi S, Bak SH, et al. Longitudinal monitoring of EGFR mutations in plasma predicts outcomes of NSCLC patients treated with EGFR TKIs: Korean Lung Cancer Consortium (KLCC-12-02). Oncotarget. 2016;7(6):6984–93.

Shepherd FA, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Mok T, Wu Y-L, Han J-Y, Ahn M-J, et al. Early clearance of plasma EGFR mutations as a predictor of response to osimertinib in the AURA3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):9027.

Sorensen BS, Wu L, Wei W, Tsai J, Weber B, Nexo E, et al. Monitoring of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-sensitizing and resistance mutations in the plasma DNA of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer during treatment with erlotinib. Cancer. 2014;120(24):3896–901.

Chabon JJ, Simmons AD, Lovejoy AF, Esfahani MS, Newman AM, Haringsma HJ, et al. Circulating tumour DNA profiling reveals heterogeneity of EGFR inhibitor resistance mechanisms in lung cancer patients. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11815.

Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Lin C-C, Soo RA, et al. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(16):1370–9.

Remon J, Menis J, Hasan B, Peric A, De Maio E, Novello S, et al. The APPLE Trial: feasibility and activity of AZD9291 (Osimertinib) Treatment on positive PLasma T790M in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients EORTC 1613. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(5):583–8.

Rolfo C, Mack P, Scagliotti GV, Aggarwal C, Arcila ME, Barlesi F, et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced NSCLC: a consensus statement From the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(10):1647–62.

Li MM, Datto M, Duncavage EJ, Kulkarni S, Lindeman NI, Roy S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: a joint consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19(1):4–23.

Ou SHI, Nagasaka M, Zhu VW. Liquid biopsy to identify actionable genomic alterations. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:978–97.

Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra24.

Aldea M, Hendriks L, Mezquita L, Jovelet C, Planchard D, Auclin E, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis for patients with oncogene-addicted NSCLC With isolated central nervous system progression. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(3):383–91.

Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA, et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):640–9.

Yi M, Jiao D, Xu H, Liu Q, Zhao W, Han X, et al. Biomarkers for predicting efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):129.

Gandara DR, Paul SM, Kowanetz M, Schleifman E, Zou W, Li Y, et al. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a predictor of clinical benefit in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1441–8.

Büttner R, Longshore JW, López-Ríos F, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Normanno N, Rouleau E, et al. Implementing TMB measurement in clinical practice: considerations on assay requirements. ESMO Open. 2019;4(1):e000442.

Biton J, Mansuet-Lupo A, Pécuchet N, Alifano M, Ouakrim H, Arrondeau J, et al. TP53, STK11, and EGFR mutations predict tumor immune profile and the response to Anti–PD-1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(22):5710–23.

Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Gainor JF, et al. STK11/LKB1 mutations and PD-1 inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(7):822–35.

Guo N, Lou F, Ma Y, Li J, Yang B, Chen W, et al. Circulating tumor DNA detection in lung cancer patients before and after surgery. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):33519.

Chen K, Zhang J, Guan T, Yang F, Lou F, Chen W, et al. Comparison of plasma to tissue DNA mutations in surgical patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154(3):1123-31.e2.

Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545(7655):446–51.

Chaudhuri AA, Chabon JJ, Lovejoy AF, Newman AM, Stehr H, Azad TD, et al. Early detection of molecular residual disease in localized lung cancer by circulating tumor DNA profiling. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(12):1394–403.

Gai W, Sun K. Epigenetic biomarkers in cell-free DNA and applications in liquid biopsy. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(1):32.

Wu YL, Sequist LV, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y, et al. EGFR mutation detection in circulating cell-free DNA of lung adenocarcinoma patients: analysis of LUX-Lung 3 and 6. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(2):175–85.

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/recently-approved-devices/foundationone-liquid-cdx-p190032.

Papadopoulou E, Tsoulos N, Tsantikidi K, Metaxa-Mariatou V, Stamou PE, Kladi-Skandali A, et al. Clinical feasibility of NGS liquid biopsy analysis in NSCLC patients. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226853-e.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.