Abstract

Background

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a specific subtype of breast cancer with a poor prognosis due to its aggressive biological behaviour and lack of therapeutic targets. We aimed to explore some novel genes and pathways related to TNBC prognosis through bioinformatics methods as well as potential initiation and progression mechanisms.

Methods

Breast cancer mRNA data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas database (TCGA). Differential expression analysis of cancer and adjacent cancer, as well as, triple negative breast cancer and non-triple negative breast cancer were performed using R software. The key genes related to the pathogenesis were identified by functional and pathway enrichment analysis and protein–protein interaction network analysis. Based on univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model analyses, a gene signature was established to predict overall survival. Receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate the prognostic performance of our model.

Results

Based on mRNA expression profiling of breast cancer patients from the TCGA database, 755 differentially expressed overlapping mRNAs were detected between TNBC/non-TNBC samples and normal tissue. We found eight hub genes associated with the cell cycle pathway highly expressed in TNBC. Additionally, a novel six-gene (TMEM252, PRB2, SMCO1, IVL, SMR3B and COL9A3) signature from the 755 differentially expressed mRNAs was constructed and significantly associated with prognosis as an independent prognostic signature. TNBC patients with high-risk scores based on the expression of the 6-mRNAs had significantly shorter survival times compared to patients with low-risk scores (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

The eight hub genes we identified might be tightly correlated with TNBC pathogenesis. The 6-mRNA signature established might act as an independent biomarker with a potentially good performance in predicting overall survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined as a subtype of aggressive breast cancer, accounting for 10–20% of all breast cancer cases [1]. TNBC subjects lack expression of the estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and does not amplify the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [2]. TNBC is more commonly diagnosed among young women and is more prone to relapse and visceral metastasis, compared with other breast cancer subtypes [3,4,5]. Due to the absence of molecular targets, patients diagnosed with TNBC cannot receive endocrine or HER2 targeted therapy [6], increasing the difficulty of treatment for them [7]. Chemotherapy is still the main adjuvant treatment option for patients with TNBC [8]. TNBC remains a disease associated with poor prognosis and limited treatment options because many tumours are resistant to chemotherapy and rapidly relapse or metastasize after adjuvant therapy [9]. The identification of uniform targets can help achieve more effective and less toxic treatment. Hence, it is imperative and urgent to explore new therapeutic targets for TNBC [10].

Recently, many biomarkers have been developed for breast cancer. For example, CD82, a potential diagnostic biomarker for breast cancer [11]. Furthermore, seven lncRNAs (MAGI2-AS3, GGTA1P, NAP1L2, CRABP2, SYNPO2, MKI67, and COL4A6) detected to be associated with TNBC prognosis, can be promising biomarkers [12]. Advancements in microarray and high throughput sequencing technologies have provided efficient tools to help in developing more reliable biomarkers for diagnosis, survival and prognosis [13, 14]. However, the predictive power of a single gene biomarker may be insufficient. Emerging studies have found that gene signatures, including several genes, may be better alternatives [15]. To the best of our knowledge, the studies about multi-gene prognostic signatures in TNBC are very few, and the functions and mechanisms of mRNAs in TNBC remain to be further explored. Thus, it is necessary to identify more sensitive and efficient mRNA signatures for TNBC prognosis.

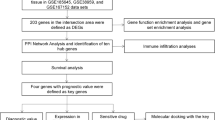

In this study, we first identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs), using 1109 BC samples and 113 matched non-cancerous samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). We identified ten hub genes associated with the cell cycle by functional enrichment analysis, protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and survival analysis. In addition, we developed a novel six-gene signature that could effectively predict TNBC survival.

Methods

Collection of clinical specimen data from the TCGA and GEO databases

The mRNA expression profiles and corresponding clinical information of breast cancer patients were downloaded from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and gene expression omnibus (GEO) databases. We collected 1109 samples with gene expression data, containing 1109 BC tumour tissues samples and 113 normal tissue samples from TCGA database. After removing patients with incomplete information, we were left with117 TNBC samples and 970 non-TNBC samples. We collected 270 samples with 58 normal breast tissue samples and 212 TNBC tissue samples from the GEO dataset of the NCBI GEO database (GSE31519, GSE9574, GSE20194, GSE20271, GSE45255, and GSE15852).

Identification of differentially expressed genes

First, we merged the RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) dataset files into a matrix file using the Perl language merge script. The gene name was converted from an Ensembl id to a gene symbol via the Ensembl database. Finally, the “edgeR” and “heatmap”R package were used to screen for differential genes between 117 TNBC and 970 other breast cancer patient subtypes and to map volcanoes. | log FC | > 1.0 and P < 0.05 were considered as the threshold value.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs were performed using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integration Discovery, DAVID version 6.8 [16]. P < 0.05 was chosen as the cut-off criterion. GO is a set of unified vocabulary to describe molecular functions (MF), biological processes (BP) and cellular components (CC) of biology, whereas KEGG analysis was performed to aid understanding of the signalling pathways involving DEGs.

PPI network construction and modules selection

A PPI network of differential genes was constructed, using STRING version 10.5 to evaluate information on protein–protein interactions [17]. Using the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) plug-in in Cytoscape 3.7.0, a visualization tool for integrating many molecular states such as expression level and interaction information into a unified conceptual framework [18], the PPI network module with densely connected regions was obtained (Degree cut-off > 15) [19].

Survival analysis

Clinical characteristic information for breast cancer was downloaded from TCGA. After removing samples with incomplete clinical overlapping DEG data, samples from 117 TNBC patients were used for further analysis. Univariate and multivariate Cox model analyses were used to identify candidate genes that were significantly associated with overall survival (OS). Based on the expression level and coefficient (β) of each gene, calculated by multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, a novel reliable prognostic gene signature was established. These TNBC patient samples were further divided into low- or high-risk groups based on the median risk score as the cut-off point. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to assess the prognostic value of the risk score. In addition, a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, using the R package “survivalROC” was constructed to assess the predictive accuracy of the gene signature for time-dependent cancer death [20]. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to evaluate the predictive ability of the gene signature for clinical outcomes.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed genes in TNBC

We used the “EDGR” and “Volcano” packages in the R software to identify differentially expressed genes between 1109 breast cancer tissue samples and 113 normal tissue samples from TCGA database (|logFC| ≥ 2 and adjusted P < 0.05), and screened out2816 up-regulated and 1095 down-regulated genes (Fig. 1a). We further analysed the DEGs between 117 TNBC and 970 non-TNBC breast cancer samples (|logFC| > 1 and adjusted P < 0.05), and identified a total of 1557 up-regulated genes and 2972 down-regulated genes (Fig. 1b). In addition, we used the Venn diagram web-tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) to cross the two sets of differential genes and found 755 overlapped DEGs (Additional file 1: Table S1), including 590 up-regulated genes (Fig. 1c) and 165 down-regulated genes (Fig. 1d).

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and Venn diagram of DEGs in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Volcano plot of all genes a between 1109 breast cancer tissue samples and 113 normal tissue samples, and b between 117 TNBC and 970 non-TNBC breast cancer samples from TCGA database. Red dots represent upregulated genes, and green dots represent downregulated genes. c Venn diagram for overlapping upregulated genes and downregulated genes in the two sets. T: Tumour; N: normal

GO term and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

GO function and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed using DAVID to expound the biological functions of 755 DEGs (Additional file 2: Table S2). The BP results indicated that DEGs were mainly significantly enriched in mitotic nuclear division, sister chromatid cohesion, cell division (Fig. 2a). MF analysis showed that DEGs were significantly enriched in microtubule motor, chemokine and structural molecule activities (Fig. 2b). CC analysis showed that the DEGs were mainly enriched in the extracellular region, chromosome centromeric region and kinetochore (Fig. 2c). In addition, the most enriched KEGG pathways were PPAR signalling, AMPK signalling and oocyte meiosis pathways (Fig. 2d).

A cell cycle related module selection by PPI Network analysis

Protein interactions among overlapping DEGs were predicted with STRING tools. A total of 148 nodes and 477 edges were displayed in the PPI network (Fig. 3) with PPI-enrichment P value < 1.0e−16. A PPI network for DEG subsets with a combined score > 0.9 was constructed to determine the candidate hub genes. Based on the PPI network of the subsets, a module with an MCODE score of 42 and 45 nodes was identified (Fig. 4a), and functional enrichment analyses showed that the genes in this module were mainly associated with the cell cycle and mitosis (Fig. 4b and Table 1). BP analysis showed that these genes were significantly enriched in microtubule-based movement, mitotic sister chromatid segregation, mitotic metaphase plate congression, cell division, and mitotic cytokinesis. For CC analysis, these genes were significantly enriched in the condensed nuclear chromosome outer kinetochore, kinetochore, and spindle midzone. MF analysis showed the genes were significantly enriched in ATP binding, microtubule motor activity, single-stranded DNA binding, and DNA replication origin binding. In addition, the results of KEGG pathway enrichment analysis suggested that the pathways were enriched as follows: cell cycle, progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, and oocyte meiosis. As a result, the eight genes correlated with cell cycle were selected as hub genes, which were CCNA2, CCNB2, CDC20, BUB1, TTK, CENPF, CENPA and CENPE (Table 2). Their expression levels were validated in 117 TNBC samples and 113 normal controls with breast cancer mRNA data from TCGA. As shown in Fig. 5, the eight mRNAs were significantly increased in TNBC compared with 113 normal control tissues (P < 0.001). We validated on the GEO database that the eight mRNA were also significantly increased compared with normal control tissues in TNBC (P < 0.001) (Additional file 3: Fig. S1).

Using Cox proportional hazards regression model, we analysed the genes in the module, but no significant gene signature was established to predict overall survival.

Construction of a six-mRNA signature for survival prediction

A total of 16 out of 755 DEGs were significantly correlated with survival time (P < 0.05) and identified by the univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model (Additional file 2: Table S3). Additionally, a prognostic gene signature, composed of six genes, was developed after using the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model. The genes include transmembrane protein 252 (TMEM252), collagen type IX alpha 3 chain (COL9A3), proline rich protein BstNI subfamily 2 (PRB2), single-pass membrane protein with coiled-coil domains 1 (SMCO1), involucrin (IVL), and submaxillary gland androgen regulated protein 3B (SMR3B) (Table 3). Patients were divided into low- and high-risk groups by the median risk score (1.070) (risk score = expression of SMR3B × 1.2141 + expression of TMEM252 × 1.6187 + expression of PRB2 × 1.4416 + expression of PRB2 × 2.0147 + expression of SMCO1 × 1.1471 + expression of COL9A3 × − 0.6101). The six-gene-based risk score distribution was presented in Fig. 6a. A highly significant difference in overall survival (OS) was detected between high- and low-risk groups (P < 0.0001) as shown in Fig. 6b. Moreover, the survival rate of the high-risk group was significantly much lower than for the low-risk group as depicted by Kaplan–Meier analysis in Fig. 6c (P < 0.0001). Time dependent ROC curve revealed that the prognostic signature presented a good performance in survival prediction, as shown in Fig. 6d and that the AUC was 0.929for 3 years OS and 0.902 for 5 years. Expression levels of the six genes in low- and high-risk groups are shown in Fig. 6e.

Prognostic gene signature of the six genes in 117 TNBC patients. a Risk score distribution; b patients’ survival status distribution; c Kaplan–Meier curves for low-risk and high-risk groups; d time-dependent ROC curves for predicting OS in TNBC patients by the risk score; e expression of the six genes in low- and high-risk groups (TCGA dataset). Gene expression values are log2-transformed

6-mRNA signature act as an independent prognostic indicator

Using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, we investigated whether the prognostic values of the six mRNA were independent of clinicopathological factors. Univariate Cox regression model showed that the risk score, race, TNM stage, N status, M status, tumour status, and radiation were significantly related to the patients’ overall survival in patients with TNBC (Table 4). In addition, multivariate Cox analysis indicated that the risk score and N stage still had remarkable independent prognostic values, with P = 0.005 and 0.025, respectively (Table 4). These results indicate that the 6-mRNA risk score was an independent prognostic indicator that can effectively predict the prognosis of TNBC patients.

Discussion

TNBC is characterized as a complex and aggressive disease with poor survival rates compared with other subtypes. Only 30% to 45% of TNBC patients achieve a complete pathological response and survival rates similar to other breast cancer subtypes [21]. The poor prognosis of patients diagnosed with TNBC is mainly due to a lack of effective targets for treatment. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more effective therapeutic targets to improve TNBC prognosis.

Misregulation of the cell cycle is a hallmark of cancer [22], disorders in mechanisms of cell cycle monitoring and proliferation cause tumour cell growth and tumour cell-specific phenomena. However, it remains unclear if misregulation of periodic mRNAs bears significance in TNBC patient pathogenesis. In this study, a total of 755 DEGs involved in TNBC were screened out from TCGA database, including 590 up-regulated and 165 down-regulated genes. We then built related PPI networks of these DEGs and identified a significant module related to cell cycle, including several key DEGs in the regulatory network of TNBC patients. Subsequently, we identified eight periodic core genes (CCNA2, CCNB2, CDC20, BUB1, TTK, CENPF, CENPA, and CENPE) in the PPI network with higher capacity for PPIs. Coincidentally, all of them were up-regulated genes in TNBC (Fig. 5). CCNA2 (CyclinA2) and CCNB2 (CyclinB2) are members of the cyclin family of proteins that play key roles in the progression of G2/M transition, and have been reported to be the risk factors for resistance and recurrence [23,24,25]. Importantly, CCNA2, CCNB2, CDC20, BUB1, TTK, CENPA, and CENPE have been reported to be potential therapeutic targets for TNBC [26,27,28,29], and TTK inhibitors are currently being evaluated as anticancer therapeutics in clinical trials. These trends are highly consistent with our findings. However, there is no relevant report on CENPF in relation to TNBC; CENPF may be related in patient pathogenesis and as a novel potential therapeutic TNBC target.

Clinical pathological features (Additional file 2: Table S4) are the proper prognostic references for TNBC patients. However, recent studies have demonstrated that clinical predictors are insufficient to precisely predict patient disease outcomes. The mRNA prognostic biomarker has the robust capacity of predicting the survival status of cancer patients. For example, Papadakis et al. [30] confirmed that mRNA BAG-1 acts as a biomarker in early breast cancer prognosis, Zheng et al. [31] found that CBX2 is a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for breast cancer.

However, it is insufficient as the single gene marker to independently predict patient survival. Because a single gene is easily affected by various factors, it is difficult to provide a stable and effective prediction effect. Therefore, we used Cox model analysis to construct a gene signature that includes several genes to enhance prognostic prediction efficiency and sensitivity to TNBC. It has been widely confirmed that combined genetic models are superior to previous single gene markers in disease prediction and diagnoses [32].

In this study, we constructed a six-mRNA (TMEM252, PRB2, SMCO1, IVL, SMR3B and COL9A3) signature for efficient and sensitive prognosis of TNBC patients. A previous study reported that COL9A3 potentially contributes to the pathogenesis of canine mammary tumours [33]. In another study, using RNA-seq to identify diabetic nephropathy, the expression of TMEM252, increased in diabetic patients relative to wild-type controls [34], but we have not found any relevant studies of TMEM252 in tumours. PRB2 is a key factor in regulating ER gene expression. In MCF-7 cells, PRB2 can interact with ER-beta to interfere with ER-beta shuttle between nuclear and cytoplasm [35], whereas ER-α gene inactivation is mediated by PRB2 in ER-negative breast cancer cells [36]. These findings suggest that PRB2 may be considered a promising target for TNBC therapy. Only one NCBI article was found to study the function of the single-pass membrane protein with coiled-coil domains 1 (SMCO1), which may contribute to hepatocyte proliferation and have the potential to promote liver repair and regeneration [37]. However, we have not found any research on SMCO1 in breast cancer; we speculate that it may also play an important role in breast cell proliferation. Additionally, we are not aware of any specific study on SMR3B in tumours, but SMR3B amplification has been detected in osteopontin (OPN)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma [38]. Involucrin (IVL), a component of keratinocyte crosslinked envelope, is found in the cytoplasm and crosslinked with membrane proteins by transglutaminase. This gene is mapped to 1q21, among calpactin I light chain, trichohyalin, profillaggrin, loricrin, and calcyclin. However, to our knowledge, there is no research on IVL in TNBC.

As far as we know, this is the first established 6-mRNA signature for the prediction of OS time in TNBC, and we have demonstrated the independent prognostic value of this 6-mRNA signature in TNBC.

Conclusions

In summary, through bioinformatic analysis, we identified eight hub genes, correlated with cell cycle, that might be tightly correlated with TNBC pathogenesis. Besides, we constructed a 6-mRNA signature which may act as a potential prognostic biomarker in patients with TNBC, and the prognostic model presented a good performance in OS prediction at 3 and 5 years. These findings will provide some guidance for future TNBC prognosis and molecular targeted therapy. However, our research is based on data analysis, and biological experiments are urgently needed to verify the biological roles of these predictive mRNAs in TNBC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in The Cancer Genome Atlas database and additional files.

Abbreviations

- TNBC:

-

triple-negative breast cancer

- GEO:

-

gene expression omnibus

- ER:

-

estrogen receptor

- PR:

-

progesterone receptor

- HER2:

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- DEG:

-

differentially expressed gene

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- PPI:

-

protein–protein interaction

- RFS:

-

relapse-free survival

- MF:

-

molecular functions

- BP:

-

biological processes

- CC:

-

cellular components

References

Cejalvo JM, Martinez de Duenas E, Galvan P, Garcia Recio S, Burgues Gasion O, Pare L, Antolin S, Martinello R, Blancas I, Adamo B, et al. Intrinsic subtypes and gene expression profiles in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(9):2213–21.

Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48.

Haffty BG, Yang Q, Reiss M, Kearney T, Higgins SA, Weidhaas J, Harris L, Hait W, Toppmeyer D. Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(36):5652–7.

Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2329–34.

Malorni L, Shetty PB, De Angelis C, Hilsenbeck S, Rimawi MF, Elledge R, Osborne CK, De Placido S, Arpino G. Clinical and biologic features of triple-negative breast cancers in a large cohort of patients with long-term follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(3):795–804.

Burstein MD, Tsimelzon A, Poage GM, Covington KR, Contreras A, Fuqua SA, Savage MI, Osborne CK, Hilsenbeck SG, Chang JC, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies novel subtypes and targets of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(7):1688–98.

Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(7):2750–67.

Hwang SY, Park S, Kwon Y. Recent therapeutic trends and promising targets in triple negative breast cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.02.006.

Craig DW, O’Shaughnessy JA, Kiefer JA, Aldrich J, Sinari S, Moses TM, Wong S, Dinh J, Christoforides A, Blum JL, et al. Genome and transcriptome sequencing in prospective metastatic triple-negative breast cancer uncovers therapeutic vulnerabilities. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(1):104–16.

Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(11):674–90.

Wang X, Zhong W, Bu J, Li Y, Li R, Nie R, Xiao C, Ma K, Huang X, Li Y. Exosomal protein CD82 as a diagnostic biomarker for precision medicine for breast cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.22960.

Tian T, Gong Z, Wang M, Hao R, Lin S, Liu K, Guan F, Xu P, Deng Y, Song D, et al. Identification of long non-coding RNA signatures in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:103.

Kulasingam V, Diamandis EP. Strategies for discovering novel cancer biomarkers through utilization of emerging technologies. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(10):588–99.

Chen B, Tang H, Chen X, Zhang G, Wang Y, Xie X, Liao N. Transcriptomic analyses identify key differentially expressed genes and clinical outcomes between triple-negative and non-triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:179–90.

Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhao Z, Lv Q. A four-gene signature predicts the efficacy of paclitaxel-based neoadjuvant therapy in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(4):6046–56.

Sherman BT, da Huang W, Tan Q, Guo Y, Bour S, Liu D, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID Knowledgebase: a gene-centered database integrating heterogeneous gene annotation resources to facilitate high-throughput gene functional analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:426.

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–52.

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–504.

Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2.

Heagerty PJ, Zheng Y. Survival model predictive accuracy and ROC curves. Biometrics. 2005;61(1):92–105.

Kalimutho M, Parsons K, Mittal D, Lopez JA, Srihari S, Khanna KK. Targeted therapies for triple-negative breast cancer: combating a stubborn disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(12):822–46.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74.

Arsic N, Bendris N, Peter M, Begon-Pescia C, Rebouissou C, Gadea G, Bouquier N, Bibeau F, Lemmers B, Blanchard JM. A novel function for Cyclin A2: control of cell invasion via RhoA signaling. J Cell Biol. 2012;196(1):147–62.

Gao T, Han Y, Yu L, Ao S, Li Z, Ji J. CCNA2 is a prognostic biomarker for ER+ breast cancer and tamoxifen resistance. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91771.

Zhao QJ, Zhang J, Xu L, Liu FF. Identification of a five-long non-coding RNA signature to improve the prognosis prediction for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(30):3426–39.

Thu KL, Silvester J, Elliott MJ, Ba-Alawi W, Duncan MH, Elia AC, Mer AS, Smirnov P, Safikhani Z, Haibe-Kains B, et al. Disruption of the anaphase-promoting complex confers resistance to TTK inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(7):E1570–7.

Komatsu M, Yoshimaru T, Matsuo T, Kiyotani K, Miyoshi Y, Tanahashi T, Rokutan K, Yamaguchi R, Saito A, Imoto S, et al. Molecular features of triple negative breast cancer cells by genome-wide gene expression profiling analysis. Int J Oncol. 2013;42(2):478–506.

Naorem LD, Muthaiyan M, Venkatesan A. Integrated network analysis and machine learning approach for the identification of key genes of triple-negative breast cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(4):6154–67.

Merino VF, Cho S, Nguyen N, Sadik H, Narayan A, Talbot C Jr, Cope L, Zhou XC, Zhang Z, Gyorffy B, et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and inflammatory genes by combined treatment with epigenetic, differentiating, and chemotherapeutic agents in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):145.

Papadakis ES, Reeves T, Robson NH, Maishman T, Packham G, Cutress RI. BAG-1 as a biomarker in early breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(12):1585–94.

Zheng S, Lv P, Su J, Miao K, Xu H, Li M. Overexpression of CBX2 in breast cancer promotes tumor progression through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(3):1668–82.

Xie X, Wang J, Shi D, Zou Y, Xiong Z, Li X, Zhou J, Tang H, Xie X. Identification of a 4-mRNA metastasis-related prognostic signature for patients with breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(2):1439–47.

Borge KS, Nord S, Van Loo P, Lingjaerde OC, Gunnes G, Alnaes GI, Solvang HK, Luders T, Kristensen VN, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. Canine mammary tumours are affected by frequent copy number aberrations, including amplification of MYC and loss of PTEN. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126371.

Rubin A, Salzberg AC, Imamura Y, Grivitishvilli A, Tombran-Tink J. Identification of novel targets of diabetic nephropathy and PEDF peptide treatment using RNA-seq. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(1):936.

Macaluso M, Montanari M, Noto PB, Gregorio V, Surmacz E, Giordano A. Nuclear and cytoplasmic interaction of pRb2/p130 and ER-beta in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 7):vii27–9.

Macaluso M, Cinti C, Russo G, Russo A, Giordano A. pRb2/p130-E2F4/5-HDAC1-SUV39H1-p300 and pRb2/p130-E2F4/5-HDAC1-SUV39H1-DNMT1 multimolecular complexes mediate the transcription of estrogen receptor-alpha in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22(23):3511–7.

Zhang C, Chang C, Li D, Zhang F, Xu C. The novel protein C3orf43 accelerates hepatocyte proliferation. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2017;22:21.

Wu JC, Sun BS, Ren N, Ye QH, Qin LX. Genomic aberrations in hepatocellular carcinoma related to osteopontin expression detected by array-CGH. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136(4):595–601.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Web links and URLs

The Cancer Genome Atlas database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository). Gene expression omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Ensemble (http://asia.ensembl.org/index.html). Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integration Discovery (DAVID) (Discovery https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). STRING (https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl). Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/). Venn diagram web-tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China and Liaoning joint fund key program (No.U1608281), Overseas and Hong Kong-Macao Scholar Cooperation Research Fund (No.31828005), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81673475), Double Hundred Program for Shenyang Scientific and Technological Innovation Projects (Z18-4-020, 100040), Natural science foundation of Liaoning province (NO.2018011264-301), Liaoning Province Scientific Research Foundation (LQNK20173, 20170541024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XML, MJW, HX and MH conceived and designed the study. XML, LYJ, YYY, WJZ, LWZ, YF, HLZ, SQZ and XL collected and processed data. XML, HYM, and YYZ analyzed data. XML, YZS and YYZ prepared tables and figures. XML drafted the manuscript. MJW, MH and HX revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Differential expressed mRNAs between 1109 breast cancer tissue samples and 113 normal tissue samples. Differential expressed mRNAs between 117 TNBC and 970 non-TNBC breast cancer samples. 590 up-regulated overlapped DEGs and 165 down-regulated overlapped DEGs.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs in TNBC. Table S3. Prognostic value of the 16 genes by univariate Cox regression. Table S4. Clinical pathological parameters of patients with TNBC.

Additional file 3: Fig. S1.

Validation of the 8 hub genes correlated with cell cycle in GEO dataset. Expression values of genes are log2-transformed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, X., He, M., Zhao, Y. et al. Identification of potential key genes and pathways predicting pathogenesis and prognosis for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int 19, 172 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-019-0884-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-019-0884-0