Abstract

Background

Exploring a simple and versatile technique for direct immobilization of target enzymes from cell lysate without prior purification is urgently needed. Thus, a novel all-in-one strategy for purification and immobilization of β-1,3-xylanase was proposed, the target enzymes were covalently immobilized on silica nanoparticles via elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs)-based biomimetic silicification and SpyTag/SpyCatcher spontaneous reaction. Thus, the functional carriers that did not require the time-consuming surface modification step were quickly and efficiently prepared. These carriers could specifically immobilize the SpyTag-fused target enzymes from the cell lysate without pre-purification.

Results

The ELPs-SpyCatcher hardly leaked from the carriers (0.5%), and the immobilization yield of enzyme was up to 96%. Immobilized enzyme retained 85.6% of the initial activity and showed 88.6% of the activity recovery. Compared with free ones, the immobilized β-1,3-xylanase showed improved thermal stability, elevated storage stability and good pH tolerance. It also retained more than 70.6% of initial activity after 12 reaction cycles, demonstrating its excellent reusability.

Conclusions

The results clearly highlighted the effectiveness of the novel enzyme immobilization method proposed here due to the improvement of overall performance of immobilized enzyme in respect to free form for the hydrolysis of macromolecular substrates. Thus, it may have great potential in the conversion of algae biomass as well as other related fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Marine algae, one of the most low-cost feedstock candidates for biofuels and chemical production, contribute approximately 50% of the earth’s primary production and generate huge numbers of distinctive polysaccharides that didn’t exist in land plants [1,2,3]. As a homopolysaccharide composed of β-1,3-linked d-xylose units, β-1,3-xylan exists in the cell walls of some red and green algae instead of cellulose [4,5,6]. β-1,3-xylanase (EC3.2.1.32) could cleave β-1,3-xylosidic linkages to produce multifarious xylooligosaccharides, which play an important role in bioenergy production and the renewable chemical commodities from marine algae [7,8,9]. However, the difficultly to separate the free β-1,3-xylanases from the hydrolyzed β-1,3-xylan solution and the low reuse rate became the bottlenecks of algae biomass conversion [10]. Accordingly, the strategy of enzyme immobilization provides a useful means to circumvent these problems by saving the usage of enzyme, simplifying downstream processing and also improving operational stability [11, 12].

Moreover, enzyme purification is the well-known obstacles in developing cost-effective processes to produce the immobilized enzyme. Thus, exploring a simple and versatile technique for direct immobilization of targeted enzymes from cell lysate without prior purification steps is a desirable strategy [13]. SpyCatcher is a peptide that spontaneously forms an isopeptide bond with its partner SpyTag. The reaction could occur rapidly under mild conditions with high efficiency and specificity, and the covalent bond between them is robust to diverse harsh conditions [14,15,16,17]. Thus, SpyTag/SpyCatcher is deemed a novel and efficient molecular adhesion that plays a vital role in the immobilization of enzymes [18,19,20].

Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are known as a kind of thermally-responsive polypeptides with repeat pentapeptide motifs of Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly (where Xaa can be any amino acid other than proline) [21, 22]. As a purification tag, ELPs-based protein purification process is large-scalable, timesaving and cost-effective [23,24,25]. Recently, the cationic ELPs [KV8F-40] (where 40 repeats of the pentapeptide motifs) were demonstrated to have the capability of rapidly prepared biomimetic silica nanoparticles (NPs). The specific mineralization activity was positively correlated with the content of basic amino acids (such Lys) [26].

In this paper, we designed a novel ELPs [K5V4F-40] (where K5V4F means the ratio of K:V:F = 5:4:1, named K5 according) and with the pI value of 9.64. Then, the ELP was fused with SpyCatcher (named K5-C). The K5-C still had the capability of preparation of biomimetic silica NPs with the SpyCatcher on the surface of silica NPs. On the other hand, the target β-1,3-xylanase fused with a SpyTag was successfully expressed and the cells of host strains were ruptured by sonicator. Then the K5-C modified silica NPs (K5-C@SiO2) could spontaneously forms a covalent bond with SpyTag in the target β-1,3-xylanase (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Thus, an all-in-one strategy for purification and immobilization of the target enzymes was proposed, which would pave a new way for the preparation of covalently immobilized enzymes for research or commercial purpose.

Results and discussion

Expression and purification of the K5-C and β-1,3-xylanases

The diagrammatic sketch of the K5-C chimera was shown in Fig. 1a. The gene coding the SpyCatcher was fused to the K5V4F gene provided by the parent vector. After expressed in the host strain and purified, the purity and molecular weight of K5-C and β-1,3-xylanases (Xyl3088) were characterized by SDS-PAGE. For the purity of K5-C and Xyl3088, SDS-PAGE yielded a clear thick band of 32 kDa and 49 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1b, c), which matched their theoretical molecular weight values of 32002 Da and 48853 Da calculated by ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). The final yield of K5-C and Xyl3088 measured by BCA protein assay was 273.05 ± 11.5 mg and 13.65 ± 1.4 mg from 1 L culture, respectively. It means that the large-scale preparation of K5-C protein can be easily achieved by two rounds of ITC which requires only inexpensive reagents such as sodium chloride and simple centrifugation techniques [21, 27]. Thus, the expensive chromatographic purification processes were avoided. In addition, the K5-C has the ability of biomimetic silicification and can be used for low-cost mass production. It can be used in subsequent large-scale preparation of nanoparticles for immobilizing the targeted enzymes [22, 28]. Finally, the free β-1,3-xylanases was purified by nickel column and the quantity-calculating results revealed the Xyl3088 comprised about 92% of the total soluble proteins after purification, which can be used for further investigation into the characteristics.

Synthesis of silica nanocomposites by K5C

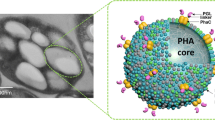

When freshly prepared TMOS was loaded to K5-C solution under room temperature, white precipitation was mediated within seconds in PBS solution (Fig. 2a, right). While, no precipitation was observed in the negative control using the same reaction system without K5-C (Fig. 2a, left), indicating that K5-C is a vital template for silica synthesis. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showed that the white precipitation mediated by K5-C were spherical with rough surfaces, and the diameters were from 200 to 600 nm (Fig. 2b). This suggested that high surface area for the anchoring of numerous SpyCatcher, which was beneficial to immobilize enzymes by covalent bond. The transmission electron microscope (TEM) images further confirmed the morphology and size of the white precipitation (Fig. 2c). Besides, strong signals for C, O, N and Si in the white silica nanosphere were analyzed by energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) experiment (Fig. 2d), indicating that K5-C fusion proteins were successfully encapsulated in the silica nanospheres (NPs). Hence, the silica NPs were organic–inorganic hybrid complexes, which can be applied for subsequent target enzyme immobilization.

Influences of K5-C concentration on the immobilization efficiency

To quantitatively analyze the mineralization activity of K5-C, the correlation between K5-C concentration and the yield of silica NPs was measured. As shown in Fig. 3a, the yield of silica was almost proportional to the amount of K5-C applied under premise controlling of the amount of silica precursor (TMOS). It was also consistent with some previous studies which silaffin, ELP(KV8F) and R5 were used to form silica nanospheres [28,29,30]. When the concentration of K5-C was 100 μmol/L, 44.97% of TMOS was converted to silica NPs. Meanwhile, the specific activity of K5-C, R5 and ELP(KV8F) was listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Under the same reaction conditions, the specific activities of silaffin and R5 were only between 2 and 4, while the activities of K5-C and KV8F reached 99.93 and 97.18, respectively. These results proved that K5-C was a silica mineralized polypeptide with high catalytic activity and the introduction of lysine enhanced the activity of the polypeptides.

To optimize K5-C immobilization efficiency, the concentration of K5-C varied from 100 to 500 μmol/L. As can be seen in Fig. 3b, higher ratios of K5-C could self-immobilize in silica NPs with the increasing concentrations of K5-C. Approximately 99% of K5-C protein were immobilized when the concentration was 300 μmol/L, and then the immobilization efficiency decreased with the increase of K5-C concentrations. This may be due to the exhaustion of TMOS, resulting in the excess of K5-C. It means that K5-C could almost self-immobilized in the silica NPs by completely consuming TMOS at 300 μmol/L.

The capacity of immobilized K5-C for applications was further investigated by studying the extent of leaching [31]. As shown in Fig. 3c, the silica NPs could firmly entrap the K5-C protein and negligible protein leakage was observed in the supernatant of silica NPs even after 56 h storage at 4 °C, indicating that K5-C was strongly embedded inside the silica NPs, while the amine-based biosilica only retain 90% of the enzyme after 24 h of storage [31, 32]. Accordingly, K5-C@SiO2 NPs was a stable carrier displaying SpyCatcher on NPs surface, resulting in efficient assembly of the target enzymes in subsequent steps.

Purification and immobilization of β-1,3-xylanases in one-step

To date, most of the enzyme immobilization techniques required prior purification of the target enzymes [33,34,35], which was a well-known process of costly and time-consuming [36]. Hence, development of a simple and versatile strategy for simultaneous purification and immobilization of the target enzymes was highly desirable [13]. Here, the silica NPs containing SpyCatcher on the surface as a carrier was loaded in the cell lysate of the chimeras of SpyTag fused β-1,3-xylanases (X-T). The immobilization and purification results were shown in Fig. 4, the supernatant of X-T cell lysate after employing K5-C@SiO2 revealed the loss of X-T band (51 kDa), while the amount and location of other impurities remained unchanged (Fig. 4, 2nd lane). Meanwhile, the loading of K5@silica NPs without SpyCatcher did not change the targeted X-T and other impurities (Fig. 4, 3rd lane), especially the target X-T. Accordingly, it clearly revealed that K5-C@SiO2 can specifically and covalently react with the X-T (via SpyCatcher and SpyTag) from the cell lysate in one-step. The immobilization efficiency and activity recovery of the captured β-1,3-xylanases (xyl3088) reached 85.4% and 88.6%, respectively.

Analysis of X-T immobilization and purification by the SDS-PAGE. Red box revealed the position of the bands corresponding to X-T. Lane: M: molecular weight marker; XC: X-T cell lysate; XCS: the supernatant of X-T cell lysate after immobilization employing K5-C@SiO2. XCE: the supernatant of X-T cell lysate after incubating with K5@SiO2

Self-immobilizing and purification systems possessing such tags offer advantages since they immobilize targeted enzymes under mild and non-toxic environment while retaining stereoselectivity and activity [37]. Besides, they would also save costs due to avoidance of crosslinkers and simplification of immobilization processes, such as purification and immobilization directly from crude cell lysate without any prior costly purification steps [38].

Effect of temperature and pH on the activity of the free and immobilized β-1,3-xylanases

The ability of an enzyme may be modulated by its immediate microenvironment [39]. So, the activities of free and immobilized Xyl3088 were assayed at temperatures ranging from 25 to 75 °C (Fig. 5a). The relative activities of immobilized β-1,3-xylanases (Xyl3088) were higher than those of the free ones over most of the temperature points, indicating that the immobilized Xyl3088 had more preferable temperature adaptability than the free one. The maximum activity of the free Xyl3088 was observed at 45 °C, while the optimum temperature of the immobilized Xyl3088 shifted up to 50 °C. The rise in optimum temperature may be owe to the reducing conformational flexibility, which requires a higher activation energy for the molecule to reorganize its proper conformation to bind to the substrate [40], thus activity even at higher temperature is one of the main advantages of immobilized enzymes [41].

The optimum pH for the activity of an enzyme was mainly dependent upon the nature of its functional groups. Besides, binding enzyme on a solid matrix may increase the pH tolerance depending on the surface and residual charges of the solid matrix [42, 43]. As shown in Fig. 5b, the optimum pH of both the free and immobilized Xyl3088 were observed at 6.6. But the immobilized Xyl3088 was found to be more stable than the free Xyl3088 from pH 4.0 to 9.0, this may be due to an increase in net charge arising from the binding of the enzyme to the silica NPs [44].

The thermal stability, storage stability and reusability of the free and immobilized β-1,3-xylanases

The activity of β-1,3-xylanases (Xyl3088) was highly sensitive to temperature, therefore, improving the thermostability of them is very important for potential industrial application. The thermostability of the free and immobilized Xyl3088 were shown in Fig. 6a, the immobilized Xyl3088 was more stable than the free one after incubation at 40 °C, 45 °C and 50 °C, respectively. This was further confirmed by the half-life test (Table 1). For example, the half-life of the free Xyl3088 reduced significantly in respect to the immobilized form (the half-life of the immobilized Xyl3088 in PBS buffer at 50 °C was about 28 min, which was 1.65-fold longer than the free one). The t-test result showed the p value was less than 0.01, revealing the differences between them were extremely significant. It also indicated that covalent immobilization might change the conformation of β-1,3-xylanases, resulting in higher thermostability towards temperature compared with the free ones [45,46,47]. Meanwhile, the storage stability of Xyl3088 was evaluated by studying the residual activities after incubating at 30 °C (Fig. 6b). Compared with the free Xyl3088, the storage stability of the immobilized one was sharply increased. After three-day storage, the free Xyl3088 only remained 21% of its initial activity, while the immobilized Xyl3088 preserved 62% of its initial activity. This indicated that silica NPs could afford suitable microenvironment and impose the steric constraints to the β-1,3-xylanase’s structure, preventing rapid denaturation. The improvement of thermostability was also suggestive of firm enzyme–support interactions, which perhaps arise from the enzyme entrapment that was possible owe to the one-step mild immobilization [31, 48].

The main advantage of immobilized enzyme was the reuse potential, which will save the cost of the enzyme. β-1,3-xylanases immobilized on silica NPs retained 93.2% of its initial enzymatic activity after five cycles of successive reusing. Even after twelve cycles, the enzyme maintained around 70.6% of its initial activity (Fig. 7). The slight, but gradual decrease of remanent activity after each cycle may be attributed to several mechanisms, including the incidental loss of silica NPs during centrifugation and transfer in each cycle, and enzyme denaturation or structural modification of β-1,3-xylanases [32, 41, 49].

Reusability of the immobilized β-1,3-xylanases (Xyl3088) in PBS (pH 7.0) at 45 °C for 12 cycles. Error bars: the standard deviation of triplicate assays. * stands for significant difference with the control (the first run) (p < 0.05), ** stands for extreme significance (p < 0.01). Data are means ± standard errors

Kinetic parameters of the free and immobilized β-1,3-xylanase

The Michaelis–Menten parameters (Km) and the catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km) of the free and immobilized β-1,3-xylanases (Xyl3088) were calculated. A slight increase in the Km was seen from the immobilized β-1,3-xylanases compared with the free ones (Table 2), indicating that the decreased affinity between enzyme and substrate. This was due to the conformational changes of β-1,3-xylanases by the immobilization carrier or a less accessibility of the active site of immobilized Xyl3088 to the substrate, especially the substrate was macromolecule β-1,3-xylan. Besides, the catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km) decreased from 113.05 mg/mL/s for the free Xyl3088 to 73.77 mg/mL/s for the immobilized Xyl3088 (p < 0.05). These results were consistent with most studies about enzyme immobilization. The decrease of active sites and the increase of mass transfer barriers may be responsible for the lower catalytic efficiency [50].

Finally, the hydrolysates of the free and immobilized Xyl3088 were investigated by thin layer chromatography (TLC) to estimate their catalytic activities. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S2, the amount and type of hydrolysates differ little, including xylose (X1), xylobiose (X2), xylotriose (X3), xylotetraose (X4), and other oligosaccharides [2, 7].While the ion chromatography (IC) of hydrolysate produced by the immobilized Xyl3088 further confirmed the results of TLC (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). This revealed that immobilized carrier did not affect the catalytic process and hydrolysis products of β-1,3-xylanase. Where in the immobilized Xyl3088 could be recycled to hydrolyze the β-1,3-xylan from the seaweed to produce xylose. It also helps develop cheaper and eco-friendly biorefinery processes that convert xylose into valuable chemicals such as 2,3-butanediol, furfural and xylitol.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

β-1,3-xylanase from the Flammeovirga pacifica strain WPAGA1 (Xyl3088, NCBI ID: MK253053), Xyl3088-SpyTag (X-T, NCBI ID: MN136290), K5V4F-SpyCatcher (K5-C, NCBI ID: MN136291) were all preserved in our lab and expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3), respectively. The protein expression was induced by 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when OD600 was between 0.5 and 0.6. After shaking at 18 °C with 180 rpm overnight, the cells were harvested and disrupted by ultrasonication. The sonicated cell suspensions were all centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 min at 13,400×g to remove the insoluble cell debris. Then the cell lysate of Xyl3088 were filtered using a 0.45 μm sterile filter and then loaded into the nickel affinity column. Finally, the Xyl3088 were eluted using elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, 250 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl respectively, pH 7.0). Moreover, the cell lysate of K5-C protein was purified by the method of Inverse transition cycling (ITC). Briefly, 2.5 mol/L NaCl crystalline was loaded to the solution of K5-C which was kept in hot bath for 15 min at 37 °C to trigger K5-C phase transition, and the aggregated K5-C was harvested by centrifugation (12,000×g, 15 min) at 37 °C. Then the isolated K5-C was resuspended and kept in ice-cool PBS buffer for 1 h, then it was centrifuged at 4 °C (12,000×g, 10 min) to remove heteroprotein precipitation. The ITC process were repeated two times to purity the K5-C proteins [27, 51].

Preparation of glycol β-1,3-xylan and β-1,3-xylooligosaccharides

Due to the β-1,3-xylan can’t obtain commercially, it was prepared from Caulerpa lentillifera (Nha trang, Vietnam) according to Iriki’s method [52], the insoluble β-1,3-xylan was then hydroxylated to form glycol β-1,3-xylan using Yamaura’s method [53]. The β-1,3-xylooligosaccharides were produced as follows, 0.1 g of β-1,3-xylan were dissolved in 10 mL of Tris–Cl buffer for 2 h under magnetic stirring at 180 rpm. Then 50 μL of free or immobilized β-1,3-xylanase was incubated with 350 μL of β-1,3-xylan suspension(1%, w/v)at 45 °C for 4 h. To terminate the enzymatic reaction, the solution was heated at 100 °C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 11,000g for 5 min. The supernatant containing the β-1,3-xylooligosaccharides was used for ion chromatography (IC) and thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis.

The hydrolysate standard of β-1,3-xylan for thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was prepared as following [54]: 0.5 g of β-1,3-xylan was suspended in 10 mL of 1 mol/L trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution and heated at 70 °C for 3 h. Then the solution was centrifuged to remove the insoluble β-1,3-xylan. Finally, the supernatant was neutralized with a 1 mol/L NaOH solution.

The first chromatographic separation was performed by an ion chromatography system (Dionex-ICS3000, American) equipping with a Dionex CarboPacPA-100 column (250 mm × 4 mm). The binary eluent was set to a flow rate of 300 µL/min using the gradient concentration of 200 mM NaOAc (100 mM NaOH). The column compartment was maintained at 30 °C throughout the run [55].

Preparation of the self-assembled silica nanoparticles

The solution of orthosilicic acid was freshly prepared by loading 1.522 g tetramethyl orthosillicate (TMOS) to 10 mL hydrochloric acid (1 mM) and kept at room temperature for 10 min [56]. The orthosilicic acid and K5-C (300 μM) were fully mixed at 1:9 (v/v) ratio for 5 min. The mixture was centrifugated at 4 °C (5000g, 3 min), and the supernatant was gathered for quantifying the unencapsulated K5-C. The new formed silica nanoparticles (NPs) containing K5-C protein were washed three times with PBS buffer to remove excess silicic acid. Then the K5-C@SiO2 NPs were resuspended in 20 mM PBS buffer to observe the leakage of K5-C protein to the supernatant within 56 h. Meanwhile, the K5-C@SiO2 NPs were resuspended in deionized water and the suspension was loaded to copper grids to do the TEM analysis. At the same time, the K5-C@SiO2 NPs were also dried overnight at 60 °C to do the SEM and EDS analysis. Finally, the silica quantification was carried out by dissolving the K5-C@SiO2 NPs in 2 mol/L NaOH for 1 h at 37 °C. The amount of silica was measured at a wavelength of 370 nm using the β-silicomolybdate method [57, 58].

One-step purification and immobilization of β-1,3-xylanase from cell lysate

1 mL cell lysate of β-1,3-xylanase was incubated with K5-C@SiO2 NPs in a tube tumbler at 37 °C for 1 h. As SpyTag and SpyCatcher could spontaneous form covalent bond in mild conditions, the silica NPs containing immobilized enzyme (K5-CT-X) were centrifuged and the supernatant was stored to quantify the immobilized and purified effect by SDS-PAGE. Meanwhile, the activity of the immobilized enzyme in PBS buffer were determined by the assay of the modified 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). The activity recovery and immobilization efficiency were calculated as following [59]:

The thermal stability, storage stability and reusability of β-1,3-xylanases

For thermal stability studies, the free and immobilized Xyl3088 were incubated in PBS buffer at 40 °C, 45 °C and 50 °C, respectively. The activities at 0 min were defined as 100%, residual activity was calculated as the percentage of initial activity at different periods (0, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 min). The half-life (t1/2) of enzyme was calculated according to Pinheiro’ method [60]. Storage stability of the free and immobilized Xyl3088 were measured by storing them in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.0) at 30 °C for 72 h. The initial activity of Xyl3088 and immobilized one were assumed as 100%, while the residual activity was investigated at each time interval.

The reusability of immobilized Xyl3088 was evaluated in a 12-cycles repeated batch experiment (45 °C and pH 7.0). After each cycle, the silica NPs containing the immobilized Xyl3088 was harvested and resuspended in the fresh β-1,3-xylan solution to start a new cycle. The activity of the first cycle was defined as 100%. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Kinetic parameters determination

Kinetic parameters of free or immobilized Xyl3088 were determined with increasing β-1,3-xylan concentrations from 1 mg/mL to 10 mg/mL by monitoring the concentration of reducing sugar at 540 nm. The Michaelis constant (Km) and maximum rate (Vmax) for free or immobilized Xyl3088 were calculated by the Michaelis–Menten model.

Conclusions

Traditional immobilization strategies need multiple steps (for example: the carrier synthesis, activation and functional modification), which in some cases may be time-consuming and tedious. Besides, enzyme purification is usually required before immobilization, which may enhance the final economic cost of the immobilized enzymes. So, a novel all-in-one strategy for purification and immobilization of the β-1,3-xylanases was proposed, the target enzymes were immobilized via covalent bond by direct treatment of SpyCatcher modified silica nanoparticles with the cell lysate of SpyTag-xylanases. The strategy of immobilization was efficient compared with the traditional methods due to its mild conditions, simplicity, all-in-one step procedure and high enzyme loading efficiency. Furthermore, the immobilized β-1,3-xylanases displayed negligible leaching (0.5%), improved thermal stability, excellent reuse potential and good storage properties in respect to the free form, which will have great potentials in algae biomass treatment. Considering the critical factor using large or insoluble substrates for immobilized enzymes, the strategy we proposed would pave a new way for efficient enzyme immobilization.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ELPs:

-

Elastin-like polypeptide

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- ITC:

-

Inverse transition cycling

- K5-C:

-

K5V4F-SpyCatcher

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- X-T:

-

Xyl3088-SpyTag

References

Hehemann JH, Boraston AB, Czjzek M. A sweet new wave: structures and mechanisms of enzymes that digest polysaccharides from marine algae. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;28:77–86.

Cai ZW, Ge HH, Yi ZW, Zeng RY, Zhnag GY. Characterization of a novel psychrophilic and halophilic beta-1,3-xylanase from deep-sea bacterium, Flammeovirga pacifica strain WPAGA1. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;118:2176–84.

Beal CM, Gerber LN, Sills DL, Huntley ME, Machesky SC, Walsh MJ, Tester JW, Archibald I, Granados J, Greene CH. Algal biofuel production for fuels and feed in a 100-ha facility: a comprehensive techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment. Algal Res. 2015;10:266–79.

Goddard-Borger ED, Sakaguchi K, Reitinger S, Watanabe N, Ito M, Withers SG. Mechanistic insights into the 1,3-xylanases: useful enzymes for manipulation of algal biomass. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(8):3895–902.

Okazaki F, Tamaru Y, Hashikawa S, Li YT, Araki T. Novel carbohydrate-binding module of beta-1,3-xylanase from a marine bacterium, Alcaligenes sp. strain XY-234. J Bacteriol. 2002;9:2399–403.

Kobayashi K, Kimura S, Heux L, Wada M. Crystal transition between hydrate and anhydrous ((1 → 3)-β-d-xylan from Penicillus dumetosus. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;97(1):105–10.

Liu T, Yi ZW, Zeng RY, Zhang GY. The first characterization of a Ca(2+)-dependent carbohydrate-binding module of β-1,3-xylanase from Flammeovirga pacifica. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2019;131:109418.

Sakaguchi K, Kiyohara M, Watanabe N, Yamaguchi K, Ito M, Kawamura T, Tanaka I. Preparation and preliminary X-ray analysis of the catalytic module of beta-1,3-xylanase from the marine bacterium Vibrio sp. AX-4. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(8):1470–2.

Kiyohara M, Sakaguchi K, Yamaguchi K, Araki T, Nakamura T, Ito M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel beta-1,3-xylanase possessing two putative carbohydrate-binding modules from a marine bacterium Vibrio sp. strain AX-4. Biochem J. 2005;388(3):949–57.

Umemoto Y, Shibata T, Araki T. D-Xylose Isomerase from a Marine Bacterium, Vibrio sp. Strain XY-214, and D-xylulose production from beta-1,3-xylan. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 2012;4(1):10–20.

Mohamad NR, Marzuki NH, Buang NA, Huyop F, Wahab RA. An overview of technologies for immobilization of enzymes and surface analysis techniques for immobilized enzymes. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2015;29(2):205–20.

Sekoai PT, Ouma CNM, Preez SP, Modisha P, Engebrecht N, Bessarabov DG, Ghimire A. Application of nanoparticles in biofuels: an overview. Fuel. 2019;237:380–97.

Vahidi AK, Yang Y, Ngo TPN, Li Z. Simple and efficient immobilization of extracellular his-tagged enzyme directly from cell culture supernatant as active and recyclable nanobiocatalyst: high-performance production of biodiesel from waste grease. ACS Catal. 2015;5:3157–61.

Wang W, Liu Z, Zhou XX, Zhu P, Guo ZQ, Yao S, Zhu MZ. Ferritin nanoparticle-based SpyTag/SpyCatcher-enabled click vaccine for tumor immunotherapy. Nanomedicine. 2019;16:69–78.

Fierle JK, Abram-Saliba J, Brioschi M, De Tiani M, Coukos G, Dunn SM. Integrating SpyCatcher/SpyTag covalent fusion technology into phage display workflows for rapid antibody discovery. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12815.

Anderson GP, Liu JL, Shriver-Lake LC, Zabetakis D, Sugiharto VA, Chen HW, Lee CR, Defang GN, Wu SJL, Venkateswaran N, Goldman E. Oriented immobilization of single-domain antibodies using SpyTag/SpyCatcher yields improved limits of detection. Anal Chem. 2019;91(15):9424–9.

Wang Y, Tian J, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Sun HX, Chang YH, Luo H. SpyTag/SpyCatcher cyclization enhances the thermostability and organic solvent tolerance of l-phenylalanine aldolase. Biotechnol Lett. 2019;41:987–94.

Lin Y, Jin W, Wang J, Cai Z, Wu S, Zhang G. A novel method for simultaneous purification and immobilization of a xylanase-lichenase chimera via SpyTag/SpyCatcher spontaneous reaction. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2018;115:29–36.

Wang J, Wang Y, Wang X, Zhang D, Wu S, Zhang G. Enhanced thermal stability of lichenase from Bacillus subtilis 168 by SpyTag/SpyCatcher-mediated spontaneous cyclization. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:79.

Sun XB, Cao JW, Wang JK, Lin HZ, Gao DY, Qian GY, Park YD, Chen ZF, Wang Q. SpyTag/SpyCatcher molecular cyclization confers protein stability and resilience to aggregation. N Biotechnol. 2019;49:28–36.

Park JE, Won JI. Thermal behaviors of elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) according to their physical properties and environmental conditions. Biotechnol Bioproc E. 2009;14(5):662–7.

Chow DC, Dreher MR, Trabbic-Carlson K, Chilkoti A. Ultra-high expression of a thermally responsive recombinant fusion protein in E. coli. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:638–46.

Yeboah A, Cohen RI, Rabolli C, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Elastin-like polypeptides: a strategic fusion partner for biologics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113(8):1617–27.

Wood DW. New trends and affinity tag designs for recombinant protein purification. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;26:54–61.

Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally responsive polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(11):1112–5.

Patwardhan SV. Biomimetic and bioinspired silica: recent developments and applications. Chem Commun. 2011;27:7567–82.

Lim DW, Trabbic-Carlson K, Mackay JA. Improved non-chromatographic purification of a recombinant protein by cationic Elastin-like polypeptides[J]. Biomacromol. 2007;8(5):1417–24.

Lin Y, Jin W, Qiu Y, Zhang G. Programmable stimuli-responsive polypeptides for biomimetic synthesis of silica nanocomposites and enzyme self-immobilization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;134:1156–69.

Kroger N. Self-assembly of highly phosphorylated silaffins and their function in biosilica morphogenesis. Science. 2002;5593:584–6.

Kroger N. Polycationic peptides from diatom biosilica that direct silica nanosphere formation. Science. 1999;286:1129–32.

Forsyth C, Yip TW, Patwardhan SV. CO2 sequestration by enzyme immobilized onto bioinspired silica. Chem Commun. 2013;49(31):3191–3.

Jo BH, Seo JH, Yang YJ, Baek K, Choi YS, Pack SP, Oh SH, Cha HJ. Bioinspired silica nanocomposite with autoencapsulated carbonic anhydrase as a robust biocatalyst for CO2 sequestration. ACS Catal. 2014;12(4):4332–40.

Ngo TP, Li A, Tiew KW, Li TZ. Efficient transformation of grease to biodiesel using highly active and easily recyclable magnetic nanobiocatalyst aggregates. Bioresour Technol. 2013;145:233–9.

Ngo TP, Zhang W, Wang W, Li Z. Reversible clustering of magnetic nanobiocatalysts for high-performance biocatalysis and easy catalyst recycling. Chem Commun. 2012;48:4585–7.

Wang W, Xu Y, Wang DIC, Li Z. Recyclable nanobiocatalyst for enantioselective sulfoxidation facile fabrication and high performance of chloroperoxidase-coated magnetic nanoparticles with iron oxide core and polymer shell. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(36):12892–3.

Cassimjee KE, Kourist R, Lindberg D, Larsen MW, Thanh NH, Widersten M, Bornscheuer UT, Berglund P. One-step enzyme extraction and immobilization for biocatalysis applications. Biotechnol J. 2011;6(4):463–9.

Peschke T, Skoupi M, Burgahn T, Gallus S, Ahmed I, Rabe KS, Niemeyer CM. Self-immobilizing fusion enzymes for compartmentalized biocatalysis. ACS Catal. 2017;11:7866–72.

Gkantzou E, Patila M, Stamatis H. Magnetic microreactors with immobilized enzymes—from assemblage to contemporary applications. Catalysts. 2018;8:282–97.

Kapoor M, Kuhad RC. Immobilization of xylanase from Bacillus pumilus strain MK001 and its application in production of xylo-oligosaccharides. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2007;2:125–38.

Zhang Z, Donaldson AA, Ma X. Advancements and future directions in enzyme technology for biomass conversion. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(4):913–9.

Cherian E, Dharmendirakumar M, Baskar G. Immobilization of cellulase onto MnO2 nanoparticles for bioethanol production by enhanced hydrolysis of agricultural waste. Chinese J Catal. 2015;36(8):1223–9.

Singh N, Srivastava G, Talat M. Cicer alpha-galactosidase immobilization onto functionalized graphene nanosheets using response surface method and its applications. Food Chem. 2014;142:430–8.

Temocin Z, Yigitoglu M. Studies on the activity and stability of immobilized horseradish peroxidase on poly(ethylene terephthalate) grafted acrylamide fiber. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2009;4:467–74.

Bajorath J, Kitson DH, Fitzgerald G, Andzelm J, Kraut J, Hagler AT. Electron redistribution on binding of a substrate to an enzyme folate and dihydrofolate reductase. Proteins. 1991;9:217–24.

Song Q, Mao Y, Wilkins M, Segato F, Prade R. Cellulase immobilization on superparamagnetic nanoparticles for reuse in cellulosic biomass conversion. AIMS Bioeng. 2016;3:264–76.

Verma ML, Chaudhary R, Tsuzuki T, et al. Immobilization of beta-glucosidase on a magnetic nanoparticle improves thermostability: application in cellobiose hydrolysis. Bioresour Technol. 2013;135:2–6.

Abraham RE, Verma ML, Barrow CJ, Puri M. Suitability of magnetic nanoparticle immobilised cellulases in enhancing enzymatic saccharification of pretreated hemp biomass. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7(1):90–102.

Ai Q, Yang D, Li Y, Shi J, Wang X, Jiang Z. Highly efficient covalent immobilization of catalase on titanate nanotubes. Biochem Eng J. 2014;83:8–15.

Gokhale AA, Lu J, Lee I. Immobilization of cellulase on magnetoresponsive graphene nano-supports. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2013;90:76–86.

Netto CGCM, Toma HE, Andrade LH. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles as versatile carriers and supporting materials for enzymes. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2013;85–86:71–92.

Ge Z, Xiong Z, Zhang D, Li X, Zhang G. Unique phase transition of exogenous fusion Elastin-like polypeptides in the solution containing polyethylene Glycol. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3560–70.

Iriki Y, Suzuki T, Nisizawa K, Miwa T. Xylan of siphonaceous green algae. Nature. 1960;187:82–3.

Yamaura I, Matsumoto T, Funatsu M, Mukai E. Purification and some properties of endo-l,3-β-D-xylanase from Pseudomonas sp. PT-5. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:921–6.

Kiyohara M, Hama Y, Yamaguchi K, Ito M. Structure of beta-1,3-xylooligosaccharides generated from Caulerpa racemosa var laete-virens beta-1,3-xylan by the action of beta-1,3-xylanase. J Biochem. 2006;3:369–73.

Cai L, Liu X, Qiu Y, Liu MQ, Zhang GY. Enzymatic degradation of algal 1,3-xylan: from synergism of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases with β-1,3-xylanases to their intelligent immobilization on biomimetic silica nanoparticles. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2020;104(12):5347–60.

Knecht MR, Wright DW. Functional analysis of the biomimetic silica eca fusiformis. Chem Commun. 2003;24:3038–9.

Naik RR, Brott LL, Clarson SJ, Stone MO. Silica-precipitating peptides isolated from a combinatorial phage display peptide library. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2002;2(1):95–100.

Wieneke R, Bernecker A, Riedel R, Sumper M, Steinem C, Geyer A. Silica precipitation with synthetic silaffin peptides. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;15:5482–6.

Sheldon RA, Van Pelt S. Enzyme immobilisation in biocatalysis: why, what and how. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;15:6223–35.

Pinheiro BB, Rios NS, Rodriguez AE, Fernandez LR, Freire TM, Fechine PBA, Dos SJCS, Goncalves LRB. Chitosan activated with divinyl sulfone: a new heterofunctional support for enzyme immobilization. Application in the immobilization of lipase B from Candida antarctica. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;130:798–809.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Li Xialan, Dr. Chen Mingxia and Dr. Lin Yuanqing for experimental support and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support from the China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (CN) (DY135-B2-07) and Subsidized Project for Postgraduates’ Innovative Fund in Scientific Research of Huaqiao University (17011087001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC and GZ designed the experiment, wrote and revised the manuscript, YC and XL purified and immobilized enzyme, YQ and ZG performed enzyme characterization and helped with experimental analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Fig. S1 The flow chart of the all-in-one strategy for purification and immobilization of β-1,3-xylanases. Fig. S2 Hydrolysis of β-1, 3-xylan by the free and immobilized β-1, 3-xylanases (Xyl3088). Lane M, molecular mass markers; lane 1, immobilized Xyl3088; lane 2, free Xyl3088. Fig. S3 Product profiles of the hydrolysis reactions of β-1, 3-xylan by immobilized Xyl3088. Table S1 Silica precipitating ability of various silica-mineralizing peptides.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, L., Chu, Y., Liu, X. et al. A novel all-in-one strategy for purification and immobilization of β-1,3-xylanase directly from cell lysate as active and recyclable nanobiocatalyst. Microb Cell Fact 20, 37 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-021-01530-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-021-01530-5