Abstract

Background

Data are limited on the association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) with systemic atherosclerosis. This study aimed to examine the relationship between MAFLD and the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of polyvascular disease (PolyVD).

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, MAFLD was diagnosed based on the presence of metabolic dysfunction (MD) and fatty liver disease (FLD). MAFLD was divided into three subtypes: MAFLD with diabetes mellitus (DM), MAFLD with overweight or obesity (OW), as well as MAFLD with lean/normal weight and at least two metabolic abnormalities. Atherosclerosis was evaluated, with vascular magnetic resonance imaging for intracranial and extracranial arteries, thoracoabdominal computed tomography angiography for coronary, subclavian, aorta, renal, iliofemoral arteries, and ankle-brachial index for peripheral arteries. The extent of plaques and stenosis was defined according to the number of these eight vascular sites affected. PolyVD was defined as the presence of stenosis in at least two vascular sites.

Results

This study included 3047 participants, with the mean age of 61.2 ± 6.7 years and 46.6% of male (n = 1420). After adjusting for potential confounders, MAFLD was associated with higher extent of plaques (cOR, 2.14, 95% CI 1.85–2.48) and stenosis (cOR, 1.47, 95% CI 1.26–1.71), and higher odds of presence of PolyVD (OR, 1.55, 95% CI 1.24–1.94) as compared with Non-MAFLD. In addition, DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD were associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD (All P < 0.05). However, lean-MAFLD was only associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques (cOR, 1.63, 95% CI 1.14–2.34). As one component of MAFLD, FLD per se was associated with the extent of plaques and stenosis in participants with MAFLD. Furthermore, FLD interacted with MD to increase the odds of presence of systemic atherosclerosis (P for interaction ≤ 0.055).

Conclusions

MAFLD and its subtypes of DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD were associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD. This study implicated that FLD might be a potential target of intervention for reducing the deleterious effects of MAFLD on systemic atherosclerosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a hallmark for the development of cardiovascular diseases [1]. It was reported that nearly 94% of the older community population had the presence of atherosclerosis, and more than 80% had multivessel atherosclerotic plaques [2]. In addition, we also observed that 53% had multivessel atherosclerotic lesions among participants with cardiovascular risk factors [3]. Compared with single-site atherosclerosis, multi-site atherosclerosis was associated with a higher rate of one-year cardiovascular events, increasing from 12% (single site) to 21% (two sites) and 26% (three sites) [4]. Assessment of systemic atherosclerosis may precisely evaluate atherosclerotic vascular lesions and find potential diseases that cannot be detected when we considered only one site [5]. Therefore, risk evaluation of multi-site atherosclerosis is of importance in asymptomatic community residents.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) was a novel terminology proposed by the international expert panel in 2019 that highlights the coexistence of fatty liver disease (FLD) and a condition of systemic metabolic dysfunction [6,7,8]. Subsequent study showed that MAFLD was a more accurate and practical indicator to discriminate the risk of extra-hepatic diseases than nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [9, 10]. Recent studies reported that MAFLD was associated with an increased risk of subclinical atherosclerosis in coronary, carotid and peripheral arteries [11,12,13]. However, most studies focused on the relationship of MAFLD with subclinical atherosclerosis in a single or few vascular beds [11, 13, 14]. There are limited data on the association of MAFLD with multivessel atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, which may hinder the understanding of whether MAFLD could increase the risk of cardiovascular events by inducing multi-site atherosclerosis and which subtype of MAFLD is most closely associated with multi-site atherosclerosis.

In this study, we therefore assessed the association of MAFLD with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of polyvascular disease (PolyVD) in community-dwelling adults.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Data were derived from the baseline survey of the Polyvascular Evaluation for Cognitive Impairment and Vascular Events (PRECISE) study. The rationale and design of the PRECISE study (NCT03178448) had been described [15]. Briefly, the PRECISE study is a community-based prospective cohort study, which used cluster sampling to enroll 3067 participants aged 50 to 75 years from six villages and four communities of Lishui city in China between May 2017 and September 2019. The exclusion criteria were as follows: contraindications for computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), life expectancy ≤ 4 years due to advanced cancers and other diseases, and mental diseases. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Beijing Tiantan Hospital (IRB approval number: KY2017-010-01) and Lishui Hospital (IRB approval number: 2016-42). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline and was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical and laboratory measurements

The data of clinical and laboratory measurements were collected by trained research coordinators at Lishui Hospital. Baseline demographics, lifestyle, medical history, family history, and medication use were collected with a standardized questionnaire through face-to-face interview. Height, body weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure were measured through physical examination. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Blood pressure was measured three times in seated position after resting for 5 min using an automated sphygmomanometer (OMRON Model HEM-7071, Omron Co.), and calculated as the average of the second and third measurements. Fasting blood samples were collected to measure blood routine indices, hepatorenal function indices, lipid profile, fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and fasting insulin. All the serum specimens were performed on the ARCHITECT c16000 auto-analyzer (Abbott, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA). FBG was measured using the hexokinase/glucose6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. HbA1c was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Serum triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL–C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured by the enzymatic colorimetric method. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration equation with an adjusted coefficient of 1.1 for the Asian population [16]. Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as FBG (mmol/L) multiplied by fasting insulin (mU/L), then divided by 22.5 [17].

Current smoking was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day on average during the past month. Current drinking was defined as responding “Current alcohol consumption” to the question “Are you drinking during past 12 months?”. Diabetes was defined as FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or 2-h post-load glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or current use of antidiabetic drugs, or any self-reported history of diabetes [18]. Hypertension was defined as systolic pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or any use of antihypertensive drugs, or a self-reported history of hypertension [19]. Dyslipidemia was defined as TC ≥ 240 mg/dL, or HDL-C < 40 mg/dL, or LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dL, or use of lipid-lowering drugs, or any self-reported history of dyslipidemia [20].

MAFLD definition

FLD was defined as fatty liver index ≥ 30, which has 71.2% of sensitivity and 71.3% of specificity for diagnosing MAFLD [21]. MAFLD was diagnosed based on the presence of FLD plus at least one of the following three conditions: type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), overweight or obesity (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 in Asians), or lean/normal weight but presence of at least two metabolic abnormalities [22]. Metabolic abnormalities include: (1) waist circumference ≥ 90 cm in Asian men and ≥ 80 cm in Asian women; (2) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or specific drug treatment; (3) TG ≥ 150 mg/dL or specific drug treatment; (4) HDL-C < 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women or specific drug treatment; (5) prediabetes; (6) HOMA-IR score ≥ 2.5; and (7) plasma high-sensitivity C-reactive protein > 2 mg/L [22]. MAFLD was further divided into three subtypes including DM-MAFLD (presence of FLD and T2DM), OW-MAFLD (presence of FLD and overweight or obesity without T2DM), and lean-MAFLD (presence of FLD and at least two metabolic abnormalities without overweight or obesity or T2DM) [22]. No metabolic dysfunction (MD) was defined as absence of T2DM, overweight or obesity, and less than two metabolic abnormalities. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the criteria of International Diabetes Federation [23]. Details regarding aforementioned definitions were described in Additional file 1: Table S1.

MRI acquisition and assessment

Intracranial and extracranial arteries were evaluated by vascular MRI on a 3.0T scanner (Ingenia 3.0T, Philips, Best, The Netherlands). MRI sequences included 3-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (3D TOF MRA), 3-dimensional isotropic high-resolution black-blood T1w vessel wall imaging (3D T1w VWI), and simultaneous noncontrast angiography and intraplaque hemorrhage imaging. The segments of intracranial arteries included the internal carotid artery, M1 and M2 segments of the middle cerebral artery, A1 and A2 segments of anterior cerebral artery, P1 and P2 segments of the posterior cerebral artery, V4 segments of the vertebral artery. The segments of extracranial arteries included the proximal internal carotid artery, V1, V2 and V3 segments of the vertebral artery, and common carotid artery. The presence of atherosclerotic plaques in intracranial and extracranial arteries was defined as eccentric wall thickening with or without luminal stenosis identified on the 3D TOF MRA or 3D T1w VWI images [24]. The presence of atherosclerotic stenosis in above arteries was defined as 50–99% of stenosis or occlusion according to the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial and the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) [25, 26].

MRI data were collected and stored in the format of digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) on discs and were analyzed by two raters (D.Y. and H.L.), who were blinded to participant’ information, at the Imaging Research Center of Tiantan Hospital. Final determination was further made by the third senior neurologist (J.J.) if there was any discrepancy. Cohens κ was calculated for interobserver agreement on the classification for presence of plaques and artery stenosis ≥ 50% (Cohen κ = 0.97 and 0.79 for intracranial artery and Cohen κ = 0.94 and 0.86 for extracranial artery).

CTA acquisition and assessment

Coronary, subclavian, aorta, renal, and iliofemoral arteries were evaluated by thoracoabdominal CTA using one dual-source CT scanner (SOMATOM Force, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany). Contrast agents iodophor (320 mg I/mL; Visipaque, GE Healthcare) was administered prior to CTA examination. CTA data were collected and stored in DICOM format on discs and were analyzed by two raters (Z.Z.Q. and Z.Z.X.), who were blinded to participant’ information, in the Core Imaging Laboratory of Keya Medical Technology (Shenzhen, China). The 3D anatomical geometry of the input CTA images was automatically reconstructed using a multitask deep learning network, and quantitative results for plaques and stenosis were calculated and characterized. Subsequently, an experienced imaging analyst identified the presence of atherosclerosis according to the 3D geometry, quantitative results, and CTA images.

The segments of coronary arteries included the left main, left descending, left circumflex, obtuse margin, diagonal, septal branch, right coronary, posterior branches, and right posterior descending segments; subclavian arteries included left and right segments; aorta arteries included arcus aortae and abdominal aorta segments; renal arteries included left and right segments; and iliofemoral arteries included common iliac, internal iliac and external iliofemoral segments. The presence of atherosclerotic plaques in coronary, subclavian, aorta, renal, and iliofemoral arteries was defined as tissue structures of at least one square millimeter area within or adjacent to the artery lumen and discernable from the vessel lumen [27]. The presence of atherosclerotic stenosis in above arteries was defined as 50–99% of stenosis or occlusion according to the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography criteria [28]. Cohens κ was calculated for interobserver agreement on the classification for presence of plaques and artery stenosis ≥ 50% (Cohen κ = 0.96 and 0.92).

ABI measurement

Peripheral arteries were evaluated by ankle-brachial index (ABI) using Doppler ultrasound (Huntleigh Health Care Ltd) in the supine position after a 10-min rest. ABI was calculated as the ratio of ankle systolic pressure divided by arm systolic pressure. Atherosclerosis in peripheral arteries was defined as ABI values of 0.9 or less [29].

Systemic atherosclerosis

Systemic atherosclerosis was reflected by three indices, including the extent of atherosclerotic plaques, extent of atherosclerotic stenosis, and presence of PolyVD.

The extent of atherosclerotic plaques was defined according to the number of 8 vascular sites affected with plaques (intracranial, extracranial, coronary, subclavian, aorta, renal, iliofemoral or peripheral arteries), and further divided into four groups, including 0, 1, 2–3, or 4–8 vascular sites [30]. Similarly, the extent of atherosclerotic stenosis was defined according to the number of 8 vascular sites affected with stenosis, and divided into four groups (0, 1, 2–3, or 4–8 vascular sites) [30]. PolyVD was defined as the presence of atherosclerotic stenosis in at least two vascular sites of above 8 arteries [31].

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristic data of continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviations) or median (interquartile ranges) and were compared by the analysis of variance or Wilcoxon rank sum test. The data of categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages) and were compared by Chi-square test.

Ordinary logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the associations of MAFLD and MAFLD subtypes with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and to calculate common odds ratio (cOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the associations of MAFLD and MAFLD subtypes with the presence of PolyVD as well as the presence of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis in a single vascular bed. Corresponding odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were calculated. Demographics, lifestyle, family history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), eGFR, and anti-atherosclerosis treatments were adjusted in models. To assess the robustness of the findings, sensitivity analyses were performed in following populations: participants without family history of ASCVD, without anti-atherosclerosis treatment, without smoking, and with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. In addition, subgroup analyses were performed to determine whether the associations were consistent even in participants with different characteristics, including age, sex, and the status of alcohol consumption.

In addition, to determine the relationship between FLD and systemic atherosclerosis without the influence of MD in participants with different subtypes of MAFLD, we performed separate analyses in MAFLD participants with different types of MD using those having MD but without FLD as the reference. We further assessed the interaction of FLD and MD on systemic atherosclerosis using binary and ordinary logistic regression analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The PRECISE study enrolled 3067 participants at baseline. We excluded 18 participants with malignancy and 2 participants without the data of height, weight, waist circumference, TG, and gamma-glutamyltransferase. Ultimately, 3047 participants were included in the final analyses (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The mean age was 61.2 ± 6.7 years, and 46.6% (n = 1420) were male. The prevalence of MAFLD was 48.2% (n = 1469). The proportions for DM-MAFLD, OW-MAFLD, and lean-MAFLD were 29.0% (n = 426), 62.1% (n = 912), and 8.9% (n = 131), respectively. Participants with MAFLD were more likely to be male, had a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and had a higher level of BMI than those with non-MAFLD (Table 1).

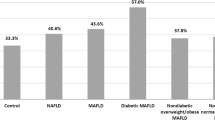

Association of MAFLD with systemic atherosclerosis

The atherosclerotic plaques, stenosis, and PolyVD were observed in 96.7%, 43.0%, and 15.8% of participants with MAFLD. In participants with DM-MAFLD, 97.9% had at least one-site atherosclerotic plaque, and 93.2% had multi-site atherosclerotic plaques, which were higher than the corresponding prevalence in OW-MAFLD and lean-MAFLD. Similar results were observed in individuals with atherosclerotic stenosis and PolyVD (Fig. 1).

Distributions of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis and presence of PolyVD in participants. MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; PolyVD, polyvascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; OW, overweight or obesity. a Extent of atherosclerotic plaques. b Extent of atherosclerotic stenosis. c PolyVD

After adjustment for demographics, lifestyle, family history of ASCVD, eGFR, and anti-atherosclerosis treatment, we found that MAFLD was associated with higher extent of atherosclerotic plaques (cOR, 2.14, 95% CI 1.85–2.48) and stenosis (cOR, 1.47, 95% CI 1.26–1.71), and higher odds of presence of PolyVD (OR, 1.55, 95% CI 1.24–1.94). In addition, DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD were associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD (All P < 0.05). However, lean-MAFLD was only associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques (cOR, 1.63, 95% CI 1.14–2.34) (Table 2). After further analysis in individual vascular bed, we found that MAFLD was more closely associated with the atherosclerotic plaques in aorta arteries (OR, 2.17, 95% CI 1.78–2.65), iliofemoral arteries (OR, 2.09, 95% CI 1.73–2.53) and the atherosclerotic stenosis in subclavian arteries (OR, 1.53, 95% CI 1.20–1.96), iliofemoral arteries (OR, 1.72, 95% CI 1.40–2.11) (Additional file 1: Table S2).

In sensitivity analyses, similar trends were observed in the participants without family history of ASCVD, without anti-atherosclerosis treatment, without smoking, and with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Additional file 1: Table S3). Furthermore, we observed similar results across different characteristics of age, sex, and the status of alcohol consumption. All P values for interaction > 0.05 (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

Association of FLD with systemic atherosclerosis in participants with MAFLD

Compared to those with MD but without FLD, we found that FLD was associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques in participants with T2DM (cOR, 1.89, 95% CI 1.33–2.69), overweight or obesity (cOR, 1.88, 95% CI 1.53–2.32), hypertension (cOR, 1.41, 95% CI 1.10–1.81), dyslipidemia (cOR, 1.45, 95% CI 1.13–1.85), and metabolic syndrome (cOR, 1.86, 95% CI 1.51–2.28). Additionally, FLD was associated with the extent of atherosclerotic stenosis in participants with overweight or obesity (cOR, 1.42, 95% CI 1.13–1.78), and dyslipidemia (cOR, 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.62). However, FLD was not associated with presence of PolyVD in participants with common MD (Fig. 2).

Association of FLD with systemic atherosclerosis in participants with common metabolic dysfunction. MD, metabolic dysfunction; FLD, fatty liver disease; PolyVD, polyvascular disease; cOR, common odds ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; Adj., adjusted; Ref., reference. All models were adjusted for sex, age, marital status, education, income, current smoking, current drinking, sleep time, sedentary time, family history of ASCVD, eGFR, lipid-lowering medication, antiplatelet medication, and anticoagulants medication. aThe extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis was defined according to the number of 8 vascular sites affected and was divided into four groups, including 0, 1, 2–3, and 4–8 vascular sites. Adjusted cOR and 95% CI were calculated by the ordinary logistic regression model. bPolyVD was defined as the presence of atherosclerotic stenosis in at least two vascular sites. Adjusted OR and 95% CI were calculated by the binary logistic regression model

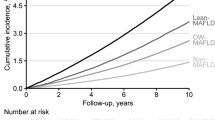

Interaction of FLD and MD on systemic atherosclerosis

After adjusting for demographics, lifestyle, family history of ASCVD, eGFR, and anti-atherosclerosis treatment, we found that FLD and MD were associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, as well as presence of PolyVD compared with the absence of FLD and MD (All P < 0.05). Additionally, FLD combined with MD was associated with higher extent of atherosclerotic plaques (cOR, 3.28, 95% CI 2.67–4.02) and stenosis (cOR, 2.34, 95% CI 1.84–2.98), and higher odds of presence of PolyVD (OR, 2.87, 95% CI 1.91–4.33). The P values for interaction of the extent of plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD were 0.055, 0.006 and 0.02, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

In this largescale community-dwelling study, we found that MAFLD was associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD. We also observed the associations of its subtypes of DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD with systemic atherosclerosis. Furthermore, as one component of MAFLD, FLD per se was associated with the extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis. Notably, FLD interacted with MD to increase the odds of presence of systemic atherosclerosis in participants with MAFLD.

MAFLD is a novel terminology redefined from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and highlights the coexistence of MD and FLD [6]. It is well established that MD, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, is a prominent contributor to the development of atherosclerosis [1]. In addition, FLD has also been reported to damage the structures and functions of vascular and promote the development of atherosclerosis by damaging vascular endothelial cell, activating the coagulation system, and increasing atherogenic lipid levels [32, 33]. This may be a potential mechanism of the association between MAFLD and systemic atherosclerosis. A cross-sectional study with 890 patients reported the association between MAFLD and subclinical atherosclerosis in coronary and carotid arteries [12]. Most importantly, recent cohort studies conducted in community-dwelling residents showed that patients with long-term MAFLD had increased odds and risk for atherosclerosis development in coronary, carotid and peripheral arteries [11, 13, 34]. However, previous studies focused on elevated carotid intima-media thickness and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity [11, 13], which merely reflect the alteration of vasculature and arterial elasticity [35, 36]. In our study, given the atherosclerotic systematicity, we assessed the association between MAFLD and systemic atherosclerosis, which further included intracranial, extracranial, renal, and iliofemoral arterial territories. Consequently, our study may provide more robust and elaborate evidence on the association between MAFLD and systemic atherosclerosis. Additionally, our findings highlighted the importance of the identification and management of MAFLD at an early stage for the prevention of systemic atherosclerosis.

MD is the main distinction among MAFLD subtypes. Although multiple MD factors involved in the development of atherosclerosis, insulin resistance may play a crucial role compared with other risk factors. Insulin resistance in the liver and muscle causes the onset of T2DM and induces other atherosclerotic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia [37, 38]. The pathogenic mechanisms linking insulin resistance to atherosclerosis include proinflammatory state, perturbation of insulin signaling at the level of the intimal cells, and induction of other metabolic conditions [39]. As T2DM and obesity are common diseases associated with high insulin resistance [40], this might explain why DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD were associated with atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis in our study. Meanwhile, those findings indicated that MAFLD patients with T2DM or obesity may desire more attention in clinical practice to prevent the poor clinical outcomes of systemic atherosclerosis.

Although FLD has been reported to promote the development of atherosclerosis [32, 33], it remains in debate whether FLD independently contributes to atherosclerosis or the association between FLD and atherosclerosis is just a reflection of shared comorbidities [3]. In this study, by using the participant with MD but without FLD as reference, we demonstrated that FLD was associated with higher extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis. Notably, we additionally demonstrated that FLD interacted with MD to promote the prevalence of systemic atherosclerosis. These results indicated that FLD per se may be an independent risk for atherosclerosis. These findings also implicated that FLD might be a potential target of intervention for prevention of atherosclerosis in participants with MAFLD.

The major strength of this study is that we comprehensively assessed multi-site atherosclerosis using advanced vascular imaging techniques in a largescale community-based population. Nevertheless, there are still several limitations. First, it is not warranted to infer causal relationships due to the cross-sectional study design of the study. More high-quality longitudinal studies are needed to verify the relationship between MAFLD and systemic atherosclerosis. Second, despite representative as a whole, potential selection bias existed in this study because the participants were enrolled from a single community region. Third, participants in our study were restricted to Chinese elderly adults, thus it should be cautious to extrapolate the findings to other populations. The findings of current study need to be further validated in a larger and more ethnically diverse cohort.

In conclusion, MAFLD and its subtypes of DM-MAFLD and OW-MAFLD were associated with higher extent of atherosclerotic plaques and stenosis, and presence of PolyVD in a community-based population. FLD interacted with MD to increase the odds of presence of systemic atherosclerosis in participants with MAFLD. This study indicated the potentially deleterious effects of MAFLD on systemic atherosclerosis and implicated that FLD might be an intervention target for the prevention of atherosclerosis in participants with MAFLD.

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ABI:

-

Ankle-brachial index

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- cOR:

-

Common odds ratio

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- FLD:

-

Fatty liver disease

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance

- MAFLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- MD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PolyVD:

-

Polyvascular disease

- PRECISE:

-

Polyvascular Evaluation for Cognitive Impairment and Vascular Events

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, Tokgozoglu L, Lewis EF. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):56.

Pan Y, Jing J, Cai X, Jin Z, Wang S, Wang Y, Zeng C, Meng X, Ji J, Li L, et al. Prevalence and vascular distribution of multiterritorial atherosclerosis among community-dwelling adults in southeast China. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6): e2218307.

Pais R, Redheuil A, Cluzel P, Ratziu V, Giral P. Relationship among fatty liver, specific and multiple-site atherosclerosis, and 10-year Framingham score. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1453–63.

Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PWF, D’Agostino R, Ohman EM, Rother J, Liau CS, Hirsch AT, Mas JL, Ikeda Y, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1197–206.

Belcaro G, Nicolaides AN, Ramaswami G, Cesarone MR, De Sanctis M, Incandela L, Ferrari P, Geroulakos G, Barsotti A, Griffin M, et al. Carotid and femoral ultrasound morphology screening and cardiovascular events in low risk subjects: a 10-year follow-up study (the CAFES-CAVE study(1)). Atherosclerosis. 2001;156(2):379–87.

Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J, International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1999–2014.

Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wai-Sun Wong V, Dufour JF, Schattenberg JM, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–9.

Polyzos SA, Kang ES, Tsochatzis EA, Kechagias S, Ekstedt M, Xanthakos S, Lonardo A, Mantovani A, Tilg H, Cote I, et al. Commentary: Nonalcoholic or metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease? The epidemic of the 21st century in search of the most appropriate name. Metabolism. 2020;113: 154413.

Lin S, Huang J, Wang M, Kumar R, Liu Y, Liu S, Wu Y, Wang X, Zhu Y. Comparison of MAFLD and NAFLD diagnostic criteria in real world. Liver Int. 2020;40(9):2082–9.

Sun DQ, Jin Y, Wang TY, Zheng KI, Rios RS, Zhang HY, Targher G, Byrne CD, Yuan WJ, Zheng MH. MAFLD and risk of CKD. Metabolism. 2021;115: 154433.

Liu S, Wang J, Wu S, Niu J, Zheng R, Bie L, Xin Z, Wang S, Lin H, Zhao Z, et al. The progression and regression of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease are associated with the development of subclinical atherosclerosis: a prospective analysis. Metabolism. 2021;120: 154779.

Bessho R, Kashiwagi K, Ikura A, Yamataka K, Inaishi J, Takaishi H, Kanai T. A significant risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease plus diabetes on subclinical atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5): e0269265.

Wang J, Liu S, Cao Q, Wu S, Niu J, Zheng R, Bie L, Xin Z, Zhu Y, Wang S, et al. New definition of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with elevated brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and albuminuria: a prospective cohort study. Front Med. 2022;16(5):714–22.

Shao C, Xu L, Lei P, Wang W, Feng S, Ye J, Zhong B. Metabolomics to identify fingerprints of carotid atherosclerosis in nonobese metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):12.

Pan Y, Jing J, Cai X, Wang Y, Wang S, Meng X, Zeng C, Shi J, Ji J, Lin J, et al. Polyvascular evaluation for cognitive impairment and vascular events (PRECISE)-a population-based prospective cohort study: Rationale, design and baseline participant characteristics. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6(1):145–51.

Teo BW, Xu H, Wang D, Li J, Sinha AK, Shuter B, Sethi S, Lee EJ. GFR estimating equations in a multiethnic Asian population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(1):56–63.

Wang M, Mei L, Jin A, Cai X, Jing J, Wang S, Meng X, Li S, Wei T, Wang Y, et al. Association between triglyceride glucose index and atherosclerotic plaques and burden: Findings from a community-based study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):204.

Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, Huang Z, Zhang D, Deng Q, Li Y, Zhao Z, Qin X, Jin D, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2515–23.

Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G, Zhang Z, Shao L, Tian Y, Dong Y, Zheng C, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2344–56.

Lu Y, Zhang H, Lu J, Ding Q, Li X, Wang X, Sun D, Tan L, Mu L, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and availability of lipid-lowering medications among primary health care settings in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9): e2127573.

Han AL. Validation of fatty liver index as a marker for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2022;14(1):44.

Eslam M, Sarin SK, Wong VW, Fan JG, Kawaguchi T, Ahn SH, Zheng MH, Shiha G, Yilmaz Y, Gani R, et al. The Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2020;14(6):889–919.

Zhu L, Spence C, Yang JW, Ma GX. The IDF definition is better suited for screening metabolic syndrome and estimating risks of diabetes in Asian American adults: evidence from NHANES 2011–2016. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3871.

Qiao Y, Guallar E, Suri FK, Liu L, Zhang Y, Anwar Z, Mirbagheri S, Xie YJ, Nezami N, Intrapiromkul J, et al. MR imaging measures of intracranial atherosclerosis in a population-based study. Radiology. 2016;280(3):860–8.

Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MZ. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(4):643–6.

Fox AJ. How to measure carotid stenosis. Radiology. 1993;186(2):316–8.

Rana JS, Dunning A, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng VY, Chinnaiyan K, et al. Differences in prevalence, extent, severity, and prognosis of coronary artery disease among patients with and without diabetes undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography: Results from 10,110 individuals from the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes): an international multicenter registry. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(8):1787–94.

Wu FZ, Wu MT. 2014 SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9(2): e3.

Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss L, Golzarian J, Gornik HL, Jaff MR, Moneta GL, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(14):1555–70.

Fernandez-Friera L, Penalvo JL, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Ibanez B, Lopez-Melgar B, Laclaustra M, Oliva B, Mocoroa A, Mendiguren J, Martinez de Vega V, et al. Prevalence, vascular distribution, and multiterritorial extent of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged cohort: The PESA (Progression of Early Subclinical Atherosclerosis) study. Circulation. 2015;131(24):2104–13.

Aday AW, Matsushita K. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease and polyvascular disease. Circ Res. 2021;128(12):1818–32.

Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J. 2012;33(10):1190–200.

Zhang L, She ZG, Li H, Zhang XJ. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a metabolic burden promoting atherosclerosis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(13):1775–99.

Meyersohn NM, Mayrhofer T, Corey KE, Bittner DO, Staziaki PV, Szilveszter B, Hallett T, Lu MT, Puchner SB, Simon TG, et al. Association of hepatic steatosis with major adverse cardiovascular events, independent of coronary artery disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(7):1480-8.e14.

Bots ML, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Lessons from the past and promises for the future for carotid intima-media thickness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(17):1599–604.

Tomiyama H, Shiina K. State of the art review: Brachial-ankle PWV. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(7):621–36.

Katakami N. Mechanism of development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(1):27–39.

Di Pino A, DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis: implications for insulin-sensitizing agents. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(6):1447–67.

Beverly JK, Budoff MJ. Atherosclerosis: pathophysiology of insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and inflammation. J Diabetes. 2020;12(2):102–4.

Burhans MS, Hagman DK, Kuzma JN, Schmidt KA, Kratz M. Contribution of adipose tissue inflammation to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Compr Physiol. 2018;9(1):1–58.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of the Polyvascular Evaluation for Cognitive Impairment and Vascular Events study for their contributions.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3602505), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073648), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2016YFC0901002), Key Science & Technologies R&D Program of Lishui City (2019ZDYF18), Zhejiang provincial program for the Cultivation of High-level Innovative Health talents, and AstraZeneca Investment (China) Co., Ltd. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZX, YH, YZ, and YP conceived the idea of paper and designed the paper. YW, YP, MW, XM, JJ, and AJ designed and conducted the study. XC, LM, SW, SL, and TW contributed to data acquisition. ZX and YH drafted the manuscript. ZX and YZ analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. YP and YH take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Beijing Tiantan Hospital (IRB approval number: KY2017-010-01) and Lishui Hospital (IRB approval number: 2016-42). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Definitions of fatty liver disease, MAFLD, MAFLD subtypes, no metabolic dysfunction, and metabolic syndrome. Table S2. Association of MAFLD and MAFLD subtypes with atherosclerosis in a single vascular bed. Table S3. Sensitivity analysis on the association of MAFLD and MAFLD subtypes with systemic atherosclerosis. Figure S1. Flowchart of the study. Figure S2. Association of MAFLD, MAFLD subtypes with systemic atherosclerosis in participants with different characteristics.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Xia, Z., Cai, X. et al. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with systemic atherosclerosis: a community-based cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22, 342 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02083-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02083-0