Abstract

Background

Pioglitazone use is known to be associated with a reduced risk of recurrent stroke in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) who have a history of stroke. However, it is unclear whether this benefit extends to patients without a history of stroke. We aimed to evaluate the association between pioglitazone use and development of first attack of ischemic stroke in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 DM.

Methods

Using longitudinal nationwide data from the 2002–2017 Korean National Health Insurance Service DM cohort, we analyzed the association between pioglitazone use and incidence of primary ischemic stroke using a nested case–control study. Among 128,171 patients with newly onset type 2 DM who were stroke-free at the time of DM diagnosis, 4796 cases of ischemic stroke were identified and matched to 23,980 controls based on age, sex, and the onset and duration of DM. The mean (standard deviation) follow-up time was 6.08 (3.34) years for the cases and controls. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between ischemic stroke and pioglitazone use were analyzed by multivariable conditional logistic regression analyses adjusted for comorbidities, cardiometabolic risk profile, and other oral antidiabetic medications.

Results

Pioglitazone use was associated with a reduced risk of first attack of ischemic stroke (adjusted OR [AOR] 0.69, 95% CI 0.60–0.80) when compared with non-use. Notably, pioglitazone use was found to have a dose-dependent association with reduced rate of ischemic stroke emergence (first cumulative defined daily dose [cDDD] quartile AOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.74–1.32; second quartile, AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.56–1.06; third quartile, AOR 0.51, 95% Cl 0.36–0.71; highest quartile, AOR 0.48, 95% CI 0.33–0.69). More pronounced risk reduction was found in patients who used pioglitazone for more than 2 years. A further stratified analysis revealed that pioglitazone use had greater protective effects in patients with risk factors for stroke, such as high blood pressure, obesity, and current smoking.

Conclusions

Pioglitazone use may have a preventive effect on primary ischemic stroke in patients with type 2 DM, particularly in those at high risk of stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with increased mortality, which is primarily attributable to cerebrovascular disease [1, 2]. In particular, the risk of stroke is three times higher in patients with DM than that in the general population [3, 4]. Insulin resistance, a pivotal pathogenic condition found in DM, plays a critical role in the development of ischemic stroke via aggravation of atherosclerosis [5]. On the other hand, insulin resistance is also considered a modifiable risk factor in terms of stroke prevention [6].

Pioglitazone is an agonist of peroxisome proliferation activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ), and one of the most potent insulin-sensitizing drugs. Recent clinical trials have demonstrated its beneficial effects on cerebrovascular outcomes by mitigating the progression of carotid intima-media thickness independent of glycemic control [7, 8]. Previous clinical studies have provided strong evidence supporting the usefulness of pioglitazone for secondary stroke prevention [9, 10]. For instance, Kim et al. recently reported that treatment with pioglitazone significantly lowered the risk of recurrent stroke in patients with DM and acute ischemic stroke [10].

Despite extensive experimental studies demonstrating the potential benefit of pioglitazone use in cerebrovascular risk, large-scale clinical studies are limited to patients with a history of previous stroke, and the preventive effects of pioglitazone use against primary ischemic stroke are often conflicting. Although the Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular Events (PROactive) revealed that treatment with pioglitazone contributed to a decreased risk of stroke compared with placebo in patients with type 2 DM with previous stroke history, there was no significant preventive effect of pioglitazone use on the development of stroke in a subgroup without prior stroke [11]. Another study reported that pioglitazone use for less than 3 years increased the risk of ischemic stroke in elderly patients with DM, whereas a recent retrospective study found that pioglitazone use prevented new-onset ischemic stroke in patients with DM who had cardiovascular risk factors [12, 13]. However, these previous studies were conducted only with participants who had cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension or hyperlipidemia; hence, their generalizability is limited. There has been no report of such beneficial effects of pioglitazone use against the first attack of ischemic stroke in the general population of patients with DM. In real-world practice, the effect of pioglitazone on stroke may vary according to different clinical characteristics in patients taking the medication and its interaction with other glucose-lowering agents.

Therefore, we aimed to examine the preventive effect of pioglitazone use on first attack of ischemic stroke in a general DM population using a nested case–control design. To account for confounding effects by indication, we assessed the cardiometabolic risk profile and prescription registry date of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 DM with no previous history of stroke.

Methods

Study design and data source

We used the 2002–2017 dataset from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS)-DM cohort. It contains data from 400,000 patients with type 2 DM, which corresponds to a sample of approximately 23% of the entire type 2 DM population in the 35–85-year age group in South Korea. This dataset includes all inpatient and outpatient medical claims data, including data on prescription drug use, diagnostic and treatment codes, and primary and secondary diagnosis codes. It also includes the National Health Screening Program (NHSP) data. Since 2000, the Korean government has implemented an obligatory NHIS, which covers up to 98% of the entire Korean population. All insured adults are eligible for the NHSP and are recommended to undergo a standardized health check-up every 1–2 years. The Korean NHIS claims database records diagnoses based on the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System (approval no. 4-2021-0127), and the approving authority waived the requirement for informed consent because of the use of deidentified patient data.

Selection of cases and controls

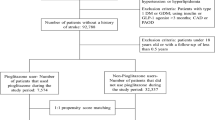

From the Korean NHIS-DM cohort, a total of 128,171 patients with newly diagnosed DM (ICD E11) with no previous history of ischemic stroke, who had undergone a health check-up between 2004 and 2012 were enrolled, and follow-up data collected until December 2017 were reviewed. Ischemic stroke was diagnosed using ICD-10 code I63. To ensure diagnostic accuracy, patients were defined as having ischemic stroke only when it was a primary diagnosis code on admission and when they underwent brain computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or magnetic resonance angiography during hospitalization because of the assumption that those with acute ischemic stroke should undergo brain imaging [14]. We excluded (i) patients who had not used antidiabetic medications (n = 39,564); (ii) patients receiving insulin treatment for more than 30 days (n = 7,027); (iii) patients with the onset of any type of stroke (ICD I60–I64) within 30 days of DM diagnosis (n = 1234); (iv) cases with no matching control (n = 235); (v) patients exposed to rosiglitazone during the study period (n = 13,291). Patients treated with rosiglitazone were excluded to avoid the confounding effect of rosiglitazone, another drug of the thiazolidinedione class withdrawn from the Korean market in 2010 due to increased cardiovascular risk concerns. The index date was defined as the date of ischemic stroke diagnosis. Control subjects were randomly selected at a 1:5 ratio from the DM cohort at the time when the case subjects were selected and were matched based on age, sex, the time point of DM diagnosis, and DM duration using incident density sampling.

Exposure to pioglitazone

Patients with total prescriptions for pioglitazone of ≥ 90 cumulative defined daily doses (cDDDs) after the onset of DM treatment were deemed pioglitazone users. This definition was applied for pioglitazone and other antidiabetic drugs including insulin, sulfonylurea, biguanide, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, and alpha-glucosidase as they may confound the data. To obtain the cDDD for each patient, we summed all the pioglitazone prescriptions dispensed during a defined period (i.e., from the onset of DM to the index date of the diagnosis of ischemic stroke) and then converted the quantity to the number of cDDDs according to the World Health Organization definition [15]. Pioglitazone exposure was described using three criteria: (i) ever-user; (ii) cDDD; and (iii) duration of the prescription. The cDDD and duration were classified by quartiles.

Potential confounders

We obtained information on selected comorbid conditions from inpatient and outpatient hospital diagnoses. The incidence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure, arterial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease (IHD), and depression and the Adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index (aDCSI) from DM diagnosis to the index date were estimated [16]. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was measured during the 1 year before the DM diagnosis. Fasting blood glucose levels, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol levels, creatinine levels, body mass index (BMI; < 18.5, 18.5–22.9, 23.0–25.0, and ≥ 25.0 kg/m2), smoking status (none, past, and current), alcohol consumption (low: < 1 time/week, moderate: 1–4 times/week, and heavy: 5–7 times/week), and physical activity (yes: ≥ 1 time/week; no: never) were measured as close as possible to the DM diagnosis date.

Statistical analyses

The characteristics of the study population were analyzed descriptively using the standardized mean difference (SMD). SMD values above 0.2 were regarded as a potential imbalance between the two groups [17]. Conditional logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate the association between pioglitazone use and ischemic stroke. We calculated the crude odds ratio (OR), adjusted OR (AOR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) for ischemic stroke between pioglitazone users and non-users. The analyses were adjusted for the following variables: hypertension, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, CCI, aDCSI, depression, fasting blood glucose levels, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol levels, creatinine levels, statin use, cardiovascular medications (aspirin, statin, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and antihypertension drugs), other antidiabetic medications, BMI, alcohol and smoking habits, and physical activity. To further assess the potential influence of preexisting risk factors for stroke, such as age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and no physical activity, we stratified the analyses to assess people with risk factors and without risk factors separately. We used incident density random sampling for our primary analysis; however, the random imbalance of covariates between pioglitazone users and non-users may have affected the main outcome. Hence, we further conducted propensity score-matching (PSM) to control for covariate imbalance that could potentially lead to selection bias. We conducted PSM using the nearest neighbor matching method and baseline covariates in a 1:4 ratio. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 128,171 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 DM with no history of stroke were included in the study. Of these patients, we identified 4,796 ischemic stroke cases and matched them with 23,980 controls (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cases and controls. Age, sex, date of DM diagnosis, and DM duration did not differ between the cases and controls after incidence density sampling. Compared with controls, cases were more likely to have hypertension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and depression. They were also more likely to use antihypertensive, antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and antiarrhythmic agents. The proportion of individuals with current smoking status and heavy alcohol intake was higher among cases than among controls. The individuals were less likely to be physically active.

Pioglitazone use and ischemic stroke development

The associations between pioglitazone use and ischemic stroke were evaluated using conditional logistic models (Table 2). During the study period, 246 patients with ischemic stroke (5.1%) and 1513 controls (6.3%) had used pioglitazone. In the univariate analysis, pioglitazone use was associated with lower odds for ischemic stroke (OR [CI], 0.79 [0.67–0.92]), compared with non-use. Upon conditional logistic regression analyses adjusted for medical comorbidities and treatment with oral antidiabetic medication, we found that pioglitazone use was significantly associated with a lower risk of primary ischemic stroke (adjusted OR 0.69, 95% CI, 0.60–0.80). Table 2 shows that pioglitazone use for extended periods has dose–response relationships with lowering risk of first onset ischemic stroke (< 171.5 cDDDs, adjusted OR 0.99; 95% CI, 0.74–1.32; 171.5–324 cDDDs, adjusted OR 0.77, 95% CI, 0.56–1.06; 325–576 cDDDs, adjusted OR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.36–0.71; ≥ 577 cDDDs, adjusted OR 0.48, 95% CI, 0.33–0.69). The greatest risk reduction was shown in pioglitazone users with the highest cDDDs (≥ 577) with an AOR of 0.48 (95% CI, 0.33–0.69), compared with non-users. Further investigation into the effect of duration of pioglitazone use showed a significant reduction in stroke risk in patients who used pioglitazone for 2 years or more (Table 3).

The protective effect of pioglitazone on first stroke was more evident in people at risk for stroke

The effect of pioglitazone use on the risk of primary stroke was evaluated in a subsequent stratified analysis (Fig. 2). Pioglitazone use remained to be associated with a lower risk of stroke regardless of age, sex, DM duration, other medical comorbidities, and lifestyle risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Of note, pioglitazone was shown to have a greater protective effect in patients with a higher risk of stroke, such as those with hypertension, IHD, longer duration of DM, obesity, current smoking, alcohol consumption, and no physical activity. These findings suggest that the beneficial effect of pioglitazone is more prominent for patients with DM with a higher risk of stroke. The subgroup analyses, which were conducted according to use of different medications, did not disclose any significant alteration in the observed effect of pioglitazone except on antiplatelets (Additional file 1: Table S1, Figure S1).

Sensitivity analyses

A total of 4006 patients with ischemic stroke and 15,398 without ischemic stroke were matched in a 1:4 ratio. The demographic characteristics of the two cohorts were similar (Additional file 1: Table S2). After matching, the pioglitazone users still exhibited a significantly lower risk of primary ischemic stroke than did non-users (AOR 0.70, 95% CI, 0.58–0.84, Additional file 1: Table S3).

Discussion

In this national, longitudinal nested case–control study, we evaluated 4,796 ischemic stroke cases and 23,980 control cases with matching variables including age, sex, time of DM diagnosis, and DM duration at a 1:5 ratio from the NHIS-DM cohort. We found that pioglitazone use was significantly associated with a reduced risk of primary ischemic stroke in patients with newly diagnosed DM. Of note, the protective effect of pioglitazone on incident ischemic stroke was greater in patients with known stroke risk factors, including hypertension, obesity, smoking, and no physical activity. These findings suggest that the increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with DM might be weakened by pioglitazone use. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale population study to assess the efficacy of pioglitazone for primary stroke prevention in Asian patients newly diagnosed with DM.

Previous studies on the cardiovascular effects of pioglitazone

Identifying the patients most likely to benefit from preventive care is a form of personalized medicine that is receiving attention in patient care. Previous studies found a protective effect of pioglitazone against recurrent stroke in patients with DM and prior stroke/ischemic attack. In the PROactive study, the stroke risk was reduced by 47% [11], and the Insulin Resistance Intervention After Stroke trial found that pioglitazone reduced the risk of ischemic events by 24% [9]. However, the association between pioglitazone use and its protective effect in primary stroke prevention in patients with DM was not clearly understood. In the PROactive study, there was no preventive effect against the development of stroke (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.73–1.52, p = 0.767) [11]. Another population-based study in Taiwan also reported no protective effects of pioglitazone on ischemic stroke prevention [18]. However, these results should be interpreted carefully since they have short pioglitazone exposure periods of less than 5 years; the mean follow-up period was 2.9 years for the PROactive study and 672 days for the Taiwanese study. According to our results, the protective effect of pioglitazone against primary stroke increased with cDDD, and there was a significantly reduced risk in people with a DM duration of more than 10 years. This suggests that the effect of pioglitazone against primary stroke may not have been clearly revealed in the previous randomized controlled trials due to their short follow-up periods.

Recently, the effect of pioglitazone on stroke has been expanded to prediabetes or patients without a history of stroke. In the prediabetic population, good adherence to pioglitazone had a HR of 0.64 for stroke compared to placebo [19]. In a population-based study of 7,574 pioglitazone users and 32,337 non-pioglitazone users from the National Health Insurance Research Database, those who used pioglitazone has a lower risk of ischemic stroke (HR 0.78; 95% CI: 0.62–0.95) [12]. However, the study population was limited to patients with DM who had at least one cardiovascular risk factor, i.e., hyperlipidemia or hypertension, which may have caused selection bias. In this study, we found that pioglitazone use has a favorable effect on decreasing the risk of primary ischemic stroke in patients with newly diagnosed DM. In addition, the preventive impact was particularly significant with a high cDDD of pioglitazone use, or in patients with comorbid stroke risk factors, i.e., hypertension, IHD, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and no physical activity.

There are concerns about the adverse effects of pioglitazone, such as increased fluid retention, weight gain, and heart failure [20]. Since the evidence is still equivocal, this may have affected the decision of physicians to actively prescribe the drug. However, recent studies reported that those risks may be minimized by lowering the dosage [21] or through combination therapy with a sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or glucagon-like peptide -1 (GLP1) receptor agonist [22,23,24]. Pioglitazone added to metformin as a secondary oral antidiabetic agent has been reported to reduce the cardiovascular risk in patients with DM compared with sulfonylurea added to metformin [25]. Considering that most patients with DM receive additional medication other than metformin, pioglitazone, which is now generically available, may present a more affordable cost-effective cardioprotective option than SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP1 receptor agonist [26]. Clinical studies have shown no reduction or a slight reduction in major cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events through intensive glycemic control [27]. Rather, treatment of preexisting traditional cerebrovascular risk factors has consistently been associated with major cerebrovascular benefits in patients with DM [28,29,30,31,32]. Therefore, our results may provide an armamentarium to physicians committed to cardiovascular prevention in patient care and a rationale for using pioglitazone in patients at high risk of stroke.

Mechanism of cardiovascular protection by pioglitazone

The exact mechanism underlying the association between pioglitazone use and reduced cardiovascular risk is uncertain. Thiazolidinediones are insulin-sensitizing antidiabetics agents that act through PPAR-γ to cause a durable improvement in glycemic control in patients with type 2 DM [33, 34]. In addition to glycemic control, pioglitazone also has a favorable effect on the plasma lipid profile; it reduces the levels of triglyceride and free fatty acid and increases the levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [35]. More importantly, since PPAR-γ receptors are expressed in endothelial cells, arterial smooth muscle cells, and monocytes/macrophages, pioglitazone exerts direct anti-atherogenic effects on the arterial wall and has a direct anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect against ischemic injury while also promoting neuronal regeneration [36,37,38,39]. A recent discovery suggests that pioglitazone may improve memory impairment by increasing low-density lipoprotein related receptor protein expression in the hippocampus, indicating that the effect of pioglitazone may extend to neuroprotection [40].

Limitations

As this study was a population-based nested case–control study using a claims database, there were several limitations. The patients included in this study may not have taken their prescribed medication or the dose prescribed, leading to exposure misclassification. Although adjustment was made for various potential confounding parameters including baseline laboratory data, other glucose-lowering agents, and lifestyle information in the analyses, data on the severity of index stroke and hemoglobin A1c levels, which are strong prognostic factors in stroke patients, were not collected due to the lack of detailed clinical information. However, we further evaluated the interaction between pioglitazone and known risk factors and provided evidence that pioglitazone may be beneficial to people at risk. This was an observational study, not a randomized trial, and, therefore, we should also consider the possibility of hidden bias between patients who received pioglitazone and those who did not. Despite adjustment for some differences in baseline characteristics, residual unidentified confounders may influence the relationship between pioglitazone use and stroke risk. In this study, only a small proportion of patients received pioglitazone, which could result in biased estimates. Although administrative databases are increasingly used for clinical research, such studies are potentially susceptible to measurement errors arising from coding inaccuracies. To mitigate this weakness, we applied the definition that was validated from previous studies using the Korean NHIS cohort [10]. Lastly, we were unable to evaluate the potential adverse effects of pioglitazone such as weight gain, fluid retention, and fracture. Although we reported that there is a reduced risk of stroke according to the cDDD of pioglitazone, further research is needed to find the optimal dose that minimizes drug-related adverse events in addition to potential benefits. In addition, a large-scale prospective study is necessary to determine the long-term drug safety profile of pioglitazone.

Conclusion

We found that pioglitazone use dose-dependently reduces the risk of primary ischemic stroke in patients with DM, particularly in individuals with a high risk of stroke. Large, prospective clinical studies are warranted to confirm the efficacy of pioglitazone use on prevention of primary ischemic stroke in patients with DM, especially in those who have additional risk factors of ischemic stroke.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are NHIS claims data and are stored on a separate server managed by the NHIS. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions by NHIS. Access to the data is regulated by Korean law and the Korean National Institute for Health and Welfare. Interested parties may submit a separate application to the NHIS for access. The NHIS accepts applications via their website (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr) and require ethics approval from the researcher’s institutional review board and a study proposal.

Abbreviations

- aDCSI:

-

Adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- cDDD:

-

Cumulative defined daily dose

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- GLP1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision

- NHSP:

-

National Health Screening Program

- OR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- PPAR-γ:

-

Proliferation activated receptor γ

- PROactive:

-

Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular Events

- PSM:

-

Propensity score-matching

- SGLT2:

-

Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

References

Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):83.

Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50.

Almdal T, Scharling H, Jensen JS, Vestergaard H. The independent effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on ischemic heart disease, stroke, and death: a population-based study of 13 000 men and women with 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1422–6.

Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2215–22.

Deng XL, Liu Z, Wang C, Li Y, Cai Z. Insulin resistance in ischemic stroke. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32(5):1323–34.

Hankey GJ, Feng TZ. Insulin resistance a possible causal and treatable risk factor for ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(10):1177–8.

Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Young LH, Furie KL, Gorman M, Lovejoy AM, et al. Pioglitazone prevents diabetes in patients with insulin resistance and cerebrovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(10):1684–92.

Langenfeld MR, Forst T, Hohberg C, Kann P, Lübben G, Konrad T, et al. Pioglitazone decreases carotid intima-media thickness independently of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from a controlled randomized study. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2525–31.

Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Furie KL, Young LH, Inzucchi SE, Gorman M, et al. Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1321–31.

Woo M-H, Lee HS, Kim J. Effect of pioglitazone in acute ischemic stroke patients with diabetes mellitus: a nested case–control study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):67.

Wilcox R, Bousser MG, Betteridge DJ, Schernthaner G, Pirags V, Kupfer S, et al. Effects of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without previous stroke: results from PROactive (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events 04). Stroke. 2007;38(3):865–73.

Hung Y-C, Chiu L-T, Huang H-Y, Bau D-T. Pioglitazone for primary stroke prevention in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors: a retrospective study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):94.

Lai SW, Lin HF, Lin CL, Liao KF. Long-term effects of pioglitazone on first attack of ischemic cerebrovascular disease in older people with type 2 diabetes: a case-control study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(31):e4455.

Kim J, Lee HS, Nam CM, Heo JH. Effects of statin intensity and adherence on the long-term prognosis after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(10):2723–30.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.ATC/DDD Index. www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 19 Febr 2018.

Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(1):15–23.

Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. P t. 2008;33(12):700–11.

Lu CJ, Sun Y, Muo CH, Chen RC, Chen PC, Hsu CY. Risk of stroke with thiazolidinediones: a ten-year nationwide population-based cohort study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36(2):145–51.

Spence JD, Viscoli CM, Inzucchi SE, Dearborn-Tomazos J, Ford GA, Gorman M, et al. Pioglitazone therapy in patients with stroke and prediabetes: a post hoc analysis of the iris randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):526–35.

Pantoni L. Potential new horizons for the prevention of cerebrovascular diseases and dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):521–2.

Adachi H, Katsuyama H, Yanai H. The low dose (7.5mg/day) pioglitazone is beneficial to the improvement in metabolic parameters without weight gain and an increase of risk for heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:247–8.

van Baar MJB, van Ruiten CC, Muskiet MHA, van Bloemendaal L, Jzerman RG, van Raalte DH. SGLT2 inhibitors in combination therapy: from mechanisms to clinical considerations in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1543–56.

DeFronzo RA. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(10):1353–62.

Rosenstock J, Vico M, Wei L, Salsali A, List JF. Effects of dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, on HbA(1c), body weight, and hypoglycemia risk in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on pioglitazone monotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1473–8.

Chan C-W, Yu C-L, Lin J-C, Hsieh Y-C, Lin C-C, Hung C-Y, et al. Glitazones and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors as the second-line oral anti-diabetic agents added to metformin reduce cardiovascular risk in Type 2 diabetes patients: a nationwide cohort observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):20.

DeFronzo RA, Inzucchi S, Abdul-Ghani M, Nissen SE. Pioglitazone: The forgotten, cost-effective cardioprotective drug for type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019;16(2):133–43.

Johnston KC, Bruno A, Pauls Q, Hall CE, Barrett KM, Barsan W, et al. Intensive vs standard treatment of hyperglycemia and functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the SHINE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(4):326–35.

Zhang H, Thijs L, Staessen JA. Blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of stroke. Hypertension. 2006;48(2):187–95.

Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, Denaxas S, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Gale CP, et al. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study in 1·9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(2):105–13.

Shah RS, Cole JW. Smoking and stroke: the more you smoke the more you stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8(7):917–32.

Curioni C, André C, Veras R. Weight reduction for primary prevention of stroke in adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2006(4):CD006062.

Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Sawan C, Macko RF, Furie KL. Obesity Stroke. 2013;44(1):278–86.

DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC, Banerji M, Bray GA, Buchanan TA, et al. Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(12):1104–15.

Eldor R, DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M. In vivo actions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S162-74.

Betteridge DJ. Effects of pioglitazone on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(5):640–7.

Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JGA, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARγ promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93(2):241–52.

Law RE, Goetze S, Xi X-P, Jackson S, Kawano Y, Demer L, et al. Expression and Function of PPARγ; in rat and human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2000;101(11):1311–8.

Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-γ agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391(6662):82–6.

Culman J, Nguyen-Ngoc M, Glatz T, Gohlke P, Herdegen T, Zhao Y. Treatment of rats with pioglitazone in the reperfusion phase of focal cerebral ischemia: a preclinical stroke trial. Exp Neurol. 2012;238(2):243–53.

Seok H, Lee M, Shin E, Yun MR, Lee Y-H, Moon JH, et al. Low-dose pioglitazone can ameliorate learning and memory impairment in a mouse model of dementia by increasing LRP1 expression in the hippocampus. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4414.

Acknowledgements

This study used the NHIS-DM data (NHIS-2019-1-648) created by NHIS.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Korean Association for Geriatric Psychiatry and a Faculty Research Grant from Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2018-0171).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMN had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JH, EK, DWC, and KYK contributed to the conception and design of this study DWC and CMN contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; JH and EK drafted the manuscript; DWC and CMN performed statistical analysis; and EK and CMN were responsible for supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System (approval no. 4-2021-0127), and the approving authority waived the requirement for informed consent because of the use of deidentified patient data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Additional figure and tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ha, J., Choi, DW., Kim, K.Y. et al. Pioglitazone use associated with reduced risk of the first attack of ischemic stroke in patients with newly onset type 2 diabetes: a nationwide nested case–control study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20, 152 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01339-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01339-x