Abstract

Background

Dysglycaemia defined as type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The negative impact is more apparent in the presence of hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. Thus, it seems reasonable to screen for dysglycaemia in patients treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. A simple screening algorithm would enhance the adoption of such strategy in clinical practice.

Objectives

To test the hypotheses (1) that dysglycaemia is common in patients with hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia and (2) that initial screening with the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) will decrease the need for laboratory based tests.

Methods

2395 patients (age 18–80 years) without (i) a history of CVD or TDM2, (ii) prescribed blood pressure and/or lipid lowering drugs answered the FINDRISC questionnaire and had an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and HbA1c measured.

Results

According to the OGTT 934 (39%) had previously undetected dysglycaemia (T2DM 19%, IGT 20%). Of patients, who according to FINDRISC had a low, moderate or slightly elevated risk 20, 34 and 41% and of those in the high and very high-risk category 49 and 71% had IGT or T2DM respectively. The OGTT identified 92% of patients with T2DM, FPG + HbA1c 90%, FPG 80%, 2hPG 29% and HbA1c 22%.

Conclusions

(1) The prevalence of dysglycaemia was high in patients treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. (2) Due to the high proportion of dysglycaemia in patients with low to moderate FINDRISC risk scores its initial use did not decrease the need for subsequent glucose tests. (3) FPG was the best test for detecting T2DM. Its isolated use is limited by the inability to disclose IGT. A pragmatic strategy, decreasing the demand for an OGTT, would be to screen all patients with FPG followed by OGTT in patients with IFG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dysglycaemia, defined as type 2 diabetes (T2DM) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), the commonest cause of death globally [1]. Screening for dysglycaemia is performed by means of three blood tests: glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and a 2 hour post load plasma glucose (2hPG), the latter only obtainable by means of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) [2]. Several scoring systems for estimating the future risk of T2DM have been developed. One of them, the FINDRISC questionnaire, has been validated in several European populations. FINDRISC classifies the respondent as having a low, moderate, high or very high risk of developing T2DM during the forthcoming decade. If an individual is at a high or very high risk, an OGTT is recommended for further investigation [3].

Importantly, not only T2DM but also its preceding, hyperglycaemic state IGT increases the risk of CVD [4, 5]. Other intermediate hyperglycaemic states include impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and “high-risk” glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study reported that people with “high risk” HbA1c are at increased risk of developing diabetes and CVD independent of FPG [6], but a postload glucose was not included in this study. Other population based studies among them the Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria in Europe (DECODE), a substudy of the DECODE population and the Framingham Offspring Study demonstrated that the 2hPG is a significantly stronger predictor of future CVD and all-cause mortality than FPG and HbA1c [7,8,9]. Similar findings were recently presented from a large European population of patients with coronary artery disease [10].

Screening for dysglycaemia is encouraged by the fact that T2DM can be prevented or delayed by approximately 50% with lifestyle and/or pharmacological interventions [11,12,13]. Although advocated by contemporary guidelines systematic screening of high risk people is infrequently implemented [2]. A concern is therefore that large proportions of dysglycaemic individuals remain unrecognized, thereby deprived preventive opportunities.

This study tested the hypotheses that (1) if appropriately screened the prevalence of dysglycaemia is high in patients free from CVD but treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia, and (2) that initiating screening with the FINDRISC questionnaire would limit the need for more expensive and time consuming blood tests. These hypotheses were tested within the auspices of the European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events-IV (EUROASPIRE-IV), a large cross-sectional survey.

Materials and methods

Study population

The primary care arm of EUROASPIRE IV was carried out in 14 European countries January 2014–April 2015 (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine and the UK). Within each country one or more geographical areas with a defined population were selected. A sample of general practices serving that population was identified according to the structure of the local health services.

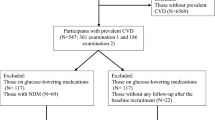

Within each general practice men and women ≥ 18 to < 80 years at the time of identification, without a history of CVD, coronary or other atherosclerotic disease, who had been prescribed one or more of the following treatments: (i) blood pressure lowering drugs and/or (ii) lipid lowering drugs and/or (iii) glucose lowering (diet and/or oral drugs and/or insulin) since ≥ 6 months to < 3 years prior to the date of interview, were retrospectively identified from practice records. The total number of such patients was 4579 of whom 1325 with a history of treatment for diabetes and 42 who lacked information on diabetes were excluded. Out of the remaining 3212 patients the information on plasma glucose or HbA1c (n = 522) and the FINDRISC questionnaire (n = 295) was incomplete leaving 2395 as the study population (Fig. 1).

Methods

Centrally trained research staff undertook data collection using standardised methods and the same instruments in all centres. They reviewed patient medical records and interviewed and examined the patients at the general practice or home at least 6 months after the prescription of blood pressure, lipid or glucose lowering therapy. A detailed description of this procedure and applied definitions have been presented elsewhere [14]. Methods of particular relevance for the present investigation are described below.

Height (kg) and weight (cm) were recorded in light indoor clothes without shoes (Scales 701 and Measuring stick model 220; SECA Medical Measuring Systems and Scales, Birmingham, UK). Waist circumference (cm) [15] was measured using a metal tape applied horizontally at the point midway in the mid-axillary line between the lowest rim of the rib cage and the tip of the hip bone (superior iliac crest) with the patient standing.

Blood pressure was measured twice on the right upper arm in a sitting position using an automatic digital sphygmomanometer (Omron M6; OMRON Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) and the mean was used for the analyses.

Physical activity was assessed with the following question: “Which of the following four alternatives describes your level of activity outside work in the best way?” (a) No physical activity weekly, (b) only light physical activity in most weeks, (c) vigorous physical activity at least 20 min once or twice a week (d) vigorous physical activity for at least 20 min three or more times a week.

The FINDRISC [16] was integrated as a part of the interview conducted by the research staff. It includes eight questions/items (age, BMI, waist circumference, intake of fruit and vegetables, physical activity, high blood pressure, history of high glucose value and family history of diabetes). Depending on the response to each question a score is set, the sum of which allocates the responding person to one of the following categories: < 7 low risk implying that 1 in 100 will develop T2DM within the next decade; 7–11 slightly elevated risk, 1 in 25 will develop T2DM; 12–14 moderate risk, 1 in 6 will develop T2DM; 15–20 high risk, 1 in 3 will develop T2DM; and > 20 very high, 1 in 2 will develop T2DM within the next decade. Applying a threshold of ≥ 9 revealed a sensitivity of 78%, a specificity of 77% and a predictive value of a negative test of 99% [3].

Laboratory investigations

Venous blood was drawn in the fasting state (≥ 10 h) into a tube containing clot activator (Venosafe, Terumo Europe, Leuven, Belgium) for lipid assays and into a potassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube for HbA1c assay. Total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglycerides were analysed in serum and HbA1c in whole blood on a clinical chemistry analyzer (Abbot Architect analyzer; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) at a central laboratory (Disease Risk Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland) accredited by Finnish Accreditation Service fulfilling the requirements of the standard SFS-EN ISO/IEC 17025:2005. Total serum cholesterol was measured using an enzymatic and high-density cholesterol (HDL-C) with a homogenous method for direct measurement while triglycerides were measured by an enzymatic glycerol phosphate oxidase method. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) cholesterol was calculated according to Friedewald’s formula [17]. Glycated HbA1c was analysed with an immunoturbidimetric method and expressed in mmol/mol according to IFCC and % according to Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). The glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated from serum creatinine by means of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (CKD-EPI) [18].

The OGTT was performed using 75 g of anhydrous glucose in 200 ml of water in the morning after at least 10 h of fasting. Blood for FPG was drawn before intake of the glucose with a dip safe from the EDTA-tube in which the HbA1c was collected. Samples for 2hPG were drawn from whole venous blood using an EDTA-tube. Plasma glucose was analysed locally with a photometric point-of-care technique (Glucose 201 + , HemoCue®, Ängelholm, Sweden). Regression analysis between the HemoCue® instrument, and standard isotope dilution gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (IDGC–MS) showed a slope of 1.051 (95% confidence interval 1.031–1.071) an intercept of − 0.222 (95% CI − 0.016 to − 0.428; r = 0.994). The mean deviation was 0.24 mmol/l (2.0%). Values obtained with the HemoCue® instrument were in 69% within 5%, in 91% within 10%, and always within 14.3% of the IDGC–MS method [19]. Since the HemoCue® method is cholesterol sensitive due to the measurement in very small volumes with higher levels of glucose with low cholesterol the glucose values were corrected according to the formula: HemoCue® glucose + 0.15 × (total cholesterol − 6). The values were converted from whole venous blood to plasma applying the formula by Carstensen et al. [19]: plasma glucose = 0.558 + 1.119 × whole blood glucose. Standardized use of the equipment was ascertained through central training of the data collectors, and retrieval of HemoCue®-cuvette storage information, and validation sheets from a selection of the participating centres.

Definitions

Hyperglycaemia defined as IFG, IGT, “high risk HbA1c” or newly detected T2DM was diagnosed according to WHO and ADA [20, 21] as outlined in Table 1.

Elevated LDL-C concentration was defined as a level ≥ 2.5 mmol/l.

Normal kidney function was defined as eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Overweight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Central obesity was defined as a waist circumference of ≥ 88 cm for women and ≥ 102 cm for men [15].

Blood pressure was defined as elevated if systolic blood pressure (SBP) was ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg.

Smoking was defined as self-reported smoking or an exhaled carbon monoxide > 10 ppm [22].

The physical activity target was defined as vigorous physical activity outside work for ≥ 20 min at least once/week.

The educational level was defined as low if only primary school or less had been completed.

Data management

The EURObservational Research Programme at the European Heart House (Nice, France) was in charge of data management. All data were collected electronically through web-based data entry using a unique identification number for country, centre and individual. The data were submitted via the Internet to the data management centre where checks for completeness, internal consistency and accuracy were performed. All data were stored under the provisions of the National Data Protection Regulations.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were summarised according to their mean and standard deviation (SD); dichotomous variables as percentages (n). For comparing characteristics of included and excluded patients p-values were obtained from linear and logistic regression models adjusted for age and gender. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS statistical software (release 9.4) at the Department of Public Health, Ghent University, Belgium.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Pertinent clinical characteristics of included (n = 2395) and excluded (n = 817) patients are presented in Table 2; those excluded from the analysis were more often smokers, less physically active and had a lower educational level, higher diastolic blood pressure, FPG and HbA1c and were more frequently using statins and calcium channel blockers. Among the included patients 94% had a normal kidney function and the eGFR was unrelated to FPG, 2 h-PG and HbA1c in all patients.

Glycaemic status

The distribution of T2DM by diagnostic test is presented in Fig. 2. A FPG alone identified 80% of those with previously unknown T2DM while FPG in combination with 2hPG identified 92% and FPG together with HbA1c 90% of them.

A total of 455 patients (19%) were identified as having T2DM by the OGTT of whom 396 (87%) were detected by FPG alone. Including HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol (DCCT ≥ 6.5%) as an additional diagnostic test the number of patients with newly detected T2DM increased by 13 to 468 (19.5%). Eight percent of the patients were detected by all three tests. Patients who were detected as having T2DM with HbA1c (8%) or 2hPG (10%) alone did not differ significantly from each other regarding age (mean ± SD = 59.0 ± 10.3 vs. 61.5 ± 11.9; p = 0.21), gender (males = 55.3% vs. 65.3%; p = 0.17) or FINDRISC score (mean ± SD 12.6 ± 3.5 vs. 13.9 ± 4.0; p = 0.38).

The 2hPG revealed that another 479 patients (20%) had IGT. The FPG classified 1495/2395 patients (62%) as having IFG (FPG = 5.6–6.9 mmol/l) including 395/479 of the patients with IGT. A “high risk” HbA1c [IFCC 39–47 mmol/mol (DCCT 5.7–6.4%)] was present in 72% of the total patient population.

Among the included patients 48.2–29.4% were treated with β-blockers or calcium channel blockers, respectively. The prevalence of newly detected dysglycaemia among patients on β-blockers was 41.0% (299/730) and among those without β-blockers 38.2% (634/1662) (p = 0.23 after adjustment for age and sex). About 43.4% (232/535) of the patients treated with calcium channel blockers had dysglycaemia compared to 37.8% (701/1857) in patients not treated with calcium channel blockers (p = 0.11 after adjustment for age and sex). In patients treated with statins 35.9% (256/713) had newly detected dysglycaemia compared to 40.4% (677/1678) among those who were not treated with statins (p = 0.0007 after adjustment for age and sex). Eighty-five percent of the patients were Caucasians. Among the remaining 15% 173 were Asian of whom 53 (30.6%) had newly detected T2DM. The distribution of dysglycaemia according to the different screening tests was similar to that in the Caucasian population.

FINDRISC

The distribution of patients according to FINDRISC was: low risk to develop diabetes 10% (n = 244), slightly elevated risk 36% (n = 857), moderate risk 29% (n = 686), high risk 23% (n = 549) and very high risk 3% (n = 59). The proportion of patients with T2DM detected by FPG, 2hPG and HbA1c in relation to their FINDRISC category increased linearly (Fig. 3). The relationship between FINDRISC category and dysglycaemia (T2DM and IGT combined) diagnosed by FPG and 2hPG is shown in Fig. 4. Of patients, who according to FINDRISC had a low, moderate/slightly elevated risk 20, 34 and 41% had IGT or T2DM respectively. The corresponding proportions for the high and very high-risk category were 49 and 71%.

Discussion

The main findings in this investigation of patients free from CVD but on treatment for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia were that: (1) the prevalence of previously undetected dysglycaemia was very high; (2) a large proportion of the present patient population in the lower FINDRISC categories for T2DM had dysglycaemia; (3) even if a FPG was the best single test for detecting T2DM it left a considerable proportion of patients with dysglycaemia undetected.

Dysglycaemia in the presence of other risk factors for CVD

The present data from a European primary care population consolidate that dysglycaemia is a very common and global condition in patients with one or two other risk factors for CVD. The prevalence of screen detected dysglycaemia was 37% (IGT 11%; T2DM 17%) in the Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Long-Term Outcomes Observational (IGLOO) study, based on 1377 Mediterranean participants without known CVD but with one or more cardiovascular risk factors [23]. A similar proportion, 41%, was reported by the ARIC study [24] screening 8286 middle-aged American participants with the OGTT, of whom many with hypertension, dyslipidaemia and/or central obesity. Further, 14% had screen detected T2DM in a cross-sectional population-based study from Kuwait in which more than half of the participants were overweight or obese but without any history of CVD [25].

In the Interventions in Europe and Worldwide (PREVIEW) among 424 New Zealanders with overweight and FINDRISC score of ≥ 12, about 65% had undetected prediabetes and 7% T2DM when screened with the OGTT [26]. A higher FINDRISC score was significantly associated with prediabetes and T2DM (p = 0.02). The prevalence of dysglycaemia among those with lower FINDRISC score was, however, not investigated.

The importance of dysglycaemia screening

It has since long been established that dysglycaemia is an important risk factor for future CVD [2]. Other important risk factors for CVD are dyslipidaemia and hypertension in the presence of which dysglycaemia causes a dramatic increase in the risk for future CVD [27, 28]. The outcome of dysglycaemia screening is therefore a prerequisite for the institution of a multifactorial risk factor management as strongly emphasized by contemporary guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention [2, 29]. It may be argued that patients under treatment for hypertension and/or hyperlipidaemia should have received life-style advice, the corner-stone in dysglycaemia management. Still 40% had undetected T2DM or IGT indicating a need for intensified life-style advice most likely supplemented by glucose lowering drugs in patients with newly detected T2DM. As regards IGT the experiences from the Da Qing study (11) and the Finnish diabetes prevention study [30] demonstrate that an improved life-style significantly reduced the development of overt T2DM during prolonged periods of follow up. Moreover, micro- and macro-vascular complications including cardiovascular mortality was reduced in the Da Qing study.

Opportunistic screening for dysglycaemia, as applied in the present study, is not contradicted by the ongoing debate on the value of population based screening for diabetes based on the inconclusive results of The Anglo–Danish–Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION) [31,32,33,34]. A reasonable assumption is that ADDITION, testing a community based screening programme in a general population, does not reflect the benefit of screening for dysglycaemia in a population at higher risk due to already diagnosed risk factors. In such population, an early instituted and comprehensive treatment has a more obvious rationale. A remaining question is how to screen. The willingness is by apparent reasons dependent of screening tools that are easy to handle and affordable. The simplicity of the FINDRISC questionnaire makes it easy to apply for the initiation of primary prevention in high risk people [13, 35]. In addition it is valuable for the detection of IGT, relates to markers of insulin resistance [36] and predicts CVD events and mortality [37].

FINDRISC in relation to blood glucose measurements

In the present investigation it was hypothesized that the use of FINDRISC as a first step in dysglycaemia screening would reduce the need for blood tests. This assumption could not be verified since a large proportion (20–40%) of the participants were dysglycaemic already in the low-moderate FINDRISC risk categories. The most reasonable explanation is the high overall prevalence of dysglycaemia in the present population of people treated for—hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. FINDRISC was based on a sample derived from the general population and its discriminatory ability is reported to be less in populations at higher risk [38]. Furthermore, the different FINDRISC components may differ by race and gender as reported by a subset of the ARIC study [39]. For example, waist circumference was more predictive of incident diabetes than BMI among black men but not in white women. An alternative to the FINDRISC for the prediction of dysglycaemia may to estimate lipoprotein (a), triglyceride/HDL-C ratio and triglyceride glucose index, which has been associated with insulin resistance and the risk of future incident diabetes [40,41,42].

Several studies added biochemical measures, in particular FPG to improve the predictive capacity of risk scoring models [43]. Thus, screening was based on the IFG cut point (≥ 6.1 mmol/l) in the ARIC study to be followed by a clinical detection rule based on the risk factors of the metabolic syndrome and CVD for those below this value. With this strategy 86% of those with T2DM and 66% of all hyperglycaemia cases were detected, identifying 42% of the study population as screen positive [24]. In the IGLOO study, addressing opportunistic screening strategies based on the FINDRISC in individuals with one or more cardiovascular risk factors, the best screening strategy seemed to be based on FPG measurement in all participants and the performance of OGTT only in those with a FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/l [23]. Based on this strategy, in which an OGTT was required for 56% of the studied population, 97% of the participants with T2DM and 78% of those with IGT was identified.

In the present study, the combination of FPG and 2hPG identified 92% of those with T2DM and the 2hPG another 20% with IGT. The superiority of this combination corresponds to the outcome of a previous study from EUROASPIRE IV on glycaemic screening of patients with established coronary artery disease [44] and in a recent population based study population consisting of overweight and obese subjects free from cardiovascular disease [45]. “High risk” HbA1c [DCCT 5.7–6.4% (IFCC 39–47 mmol/mol)] classified a majority (72%) of the present population as having glucose perturbations. This proportion is reasonably too high. Furthermore “high risk” HbA1c is less sensitive than IFG and IGT to detect individuals with insulin resistance and ß-cell dysfunction [46]. According to a WHO expert group, “high risk” HbA1c is a less effective diagnostic tool than FPG and 2hPG and current evidence is insufficient to make any formal recommendation on the interpretation of HbA1c levels < 6.5% [20, 47].

An alternative, limiting OGTT to 62% of the population (those with IFG), would be to start screening with a FPG continuing with an OGTT only in patients not fulfilling the criteria for T2DM. With such strategy 18% of patients with IGT would be missed. It has to be debated whether this is acceptable.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of EUROASPIRE IV is that data are based on interviews and standardised examinations of a large cross-sectional European population of well-characterised high-risk patients treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. Thus, the studied population is representative for a common at-risk group which, so far free from CVD, should be of particular interest for targeted life-style based interventions [4, 5, 48]. All tests (FPG, 2hPG and HbA1c) were uniformly undertaken by centrally trained staff members using the same methodology including a central laboratory. A limitation is that, as in almost all similar studies, dysglycaemia was based on a single glucose recording rather than, as recommended by WHO for a clinical diagnosis, repeated measurements. Moreover, it may be argued that patients who, due to missing data, were excluded had a somewhat higher risk profile (Table 2). This may, if of any importance, contribute to an underestimation of the true prevalence of dysglycaemia. Markers of dysglycaemia may vary by race and ethnicity [49, 50]. The vast majority of the present population was of Caucasian origin limiting the generalisability of the present findings to such populations.

Statin use may increase the risk for T2DM as well as β-blockers and possibly calcium channel blockers [51]. In the present study patients on statins had a lower proportion of dysglycaemia and there were no significant differences for β-blockers or calcium channel blockers. These data, derived from a cross-sectional investigation, should be looked at as descriptive for the present patient population. Accurate information on drug induced dysglycaemia can only be derived from longitudinal (cohort) studies. In contrast, the aim of the present study was to screen for undetected dysglycaemia in the presence of other risk factors and not to outline the risk for pharmacologically induced dysglycaemia.

It has been claimed that an OGTT has a limited reproducibility in particular for establishing the presence of IGT [52]. In a study by Wallander et al. [53] patients were screened with OGTT 5 days, 3 and 12 months after an AMI. Of those who were identified to have dysglycaemia at hospital discharge 93% were still classified as such, either having diabetes (64%) or IGT (29%) after 12 months. Of patients with IGT at hospital discharge 71% hade IGT or diabetes 12 months later and 29% normal glucose metabolism while 60% of patients classified with normal glucose metabolism at discharge remained normal after 12 months and 40% had developed IGT or type 2 diabetes. Thus, an OGTT seems to be reliable enough for screening purpose. Still, a second test should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, as recommended by WHO, before the institution of treatment.

Conclusions

Hidden dysglycaemia is very common in patients treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia. To apply FINDRISC as a first step of dysglycaemia screening does not provide any benefit in such populations. Of different blood tests a single HbA1c was the least efficient due to its limited ability to detect T2DM and its inability to diagnose IGT. The combination of FPG and 2hPG was the best test for detecting T2DM and the FPG was the single best test. The latter is, however, limited by the inability to detect IGT. A pragmatic strategy, decreasing the demand for an OGTT by 21%, would be to screen all patients with FPG followed by OGTT in patients with IFG. Finding simpler methods e.g. based on a 1 hour post load glucose [54] to identify individuals at high risk of progression to diabetes and CVD in the need for more targeted prevention strategies remains an important goal.

References

WHO. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/. Accessed 30 Dec 2016.

Rydén L, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, Danchin N, Deaton C, et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3035–87.

Lindström J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:725–31.

Ritsinger V, Tanoglidi E, Malmberg K, Näsman P, Rydén L, Tenerz Å, et al. Sustained prognostic implications of newly detected glucose abnormalities in patients with acute myocardial infarction: long-term follow-up of the glucose tolerance in patients with acute myocardial infarction cohort. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12:23–32.

George A, Bhatia RT, Buchanan GL, Whiteside A, Moisey RS, Beer SF, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance or newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus diagnosed during admission adversely affects prognosis after myocardial infarction: an observational study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0142045.

Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, Matsushita K, Wagenknecht L, Pankow J, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:800–11.

DECODE Study Group; on behalf of the European. Diabetes epidemiology group. glucose tolerance and cardiovascular mortality: comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:397–405.

Qiao Q, Dekker JM, de Vegt F, Nijpels G, Nissinen A, Stehouwer CD, et al. Two prospective studies found that elevated 2-hr glucose predicted male mortality independent of fasting glucose and HbA1c. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:590–6.

Meigs JB, Nathan DM, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PWF. Fasting and postchallenge glycemia and cardiovascular disease risk. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1845–50.

Shahim B, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Gyberg V, Kotseva K, Mellbin L, et al. The prognostic value of fasting plasma glucose, two-hour postload glucose, and HbA1c in patients with coronary artery disease: a report from EUROASPIRE IV: a survey from the european society of cardiology. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1233–40.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, An Y, Gong Q, Gregg EW, et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:474–80.

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–50.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Diabetes prevention program research group. reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403.

Kotseva K, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Rydén L, Jennings C, Gyberg V, et al. Lifestyle and risk factor management in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease. A report from the European Society of Cardiology European Action on Secondary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to reduce events (EUROASPIRE) IV cross-sectional survey in 14 European regions. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:2007–18.

Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–61.

https://www.mdcalc.com/findrisc-finnish-diabetes-risk-score. Accessed 15 Dec 2017.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12.

Carstensen B, Lindström J, Sundvall J, Borch-Johnsen K. Tuomilehto; DPS study group. Measurement of blood glucose: comparison between different types of specimens. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45:140–8.

World Health Organisation (WHO) Consultation. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes and intermediate hyperglycemia. 2006 [Internet]. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/diagnosis_diabetes2006/en/. Accessed 19 Jul 2016.

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:S13–22.

Middleton ET, Morice AH. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. Chest. 2000;117:758–63.

Franciosi M, Berardis GD, Rossi MCE, Sacco M, Belfiglio M, Pellegrini F, et al. Use of the diabetes risk score for opportunistic screening of undiagnosed diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1187–94.

Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Vigo A, Pankow J, Ballantyne CM, Couper D, et al. Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and other hyperglycemia states. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1338–43.

Awad AI, Alsaleh FM. 10-year risk estimation for type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease in Kuwait: a cross-sectional population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116742.

Silvestre MP, Jiang Y, Volkova K, Chisholm H, Lee W, Poppitt SD. Evaluating FINDRISC as a screening tool for type 2 diabetes among overweight adults in the PREVIEW:NZ cohort. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11:561–9.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52.

Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–44.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81.

Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, Ilanne-Parikka P, Aunola S, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised finnish diabetes prevention study (DPS). Diabetologia. 2013;56:284–93.

Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Witte DR, Borch-Johnsen K, Lauritzen T, Sandbæk A. Effect of population screening for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors on mortality rate and cardiovascular events: a controlled trial among 1,912,392 Danish adults. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2183–91.

Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Lauritzen T, Sandbæk A. Effect of screening for type 2 diabetes on risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a controlled trial among 139,075 individuals diagnosed with diabetes in Denmark between 2001 and 2009. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2192–9.

Shaw JE. Does the evidence support population-wide screening for type 2 diabetes? No. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2153–6.

Simmons D, Zgibor JC. Should we screen for type 2 diabetes among asymptomatic individuals? Yes. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2148–52.

Lindström J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Rastas M, Salminen V, Eriksson J, et al. The finnish diabetes prevention study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3230–6.

Schwarz PEH, Li J, Reimann M, Schutte AE, Bergmann A, Hanefeld M, et al. The finnish diabetes risk score is associated with insulin resistance and progression towards type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:920–6.

Silventoinen K, Pankow J, Lindström J, Jousilahti P, Hu G, Tuomilehto J. The validity of the finnish diabetes risk score for the prediction of the incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke, and total mortality. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil Off J Eur Soc Cardiol Work Groups Epidemiol Prev Card Rehabil Exerc Physiol. 2005;12:451–8.

Kengne AP, Beulens JW, Peelen LM, Moons KG, van der Schouw YT, Schulze MB, et al. Non-invasive risk scores for prediction of type 2 diabetes (EPIC-InterAct): a validation of existing models. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:19–29.

Kulkarni M, Foraker RE, McNeill AM, Girman C, Golden SH, Rosamond WD, et al. Evaluation of the modified FINDRISC to identify individuals at high risk for diabetes among middle-aged white and black ARIC study participants. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1260–6.

Paige E, Masconi KL, Tsimikas S, Kronenberg F, Santer P, Weger S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and incident type-2 diabetes: results from the prospective Bruneck study and a meta-analysis of published literature. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:38.

von Bibra H, Saha S, Hapfelmeier A, Müller G, Schwarz PEH. Impact of the triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and the hypertriglyceremic-waist phenotype to predict the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Horm Metab Res Horm Stoffwechselforschung Horm Metab. 2017;49:542–9.

Zhang M, Wang B, Liu Y, Sun X, Luo X, Wang C, et al. Cumulative increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus with increasing triglyceride glucose index in normal-weight people: the rural Chinese cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:30.

Buijsse B, Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Schulze MB. Risk assessment tools for identifying individuals at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:46.

Gyberg V, Bacquer DD, Kotseva K, Backer GD, Schnell O, Sundvall J, et al. Screening for dysglycaemia in patients with coronary artery disease as reflected by fasting glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, and HbA1c: a report from EUROASPIRE IV—a survey from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1171–7.

Meijnikman AS, De Block CEM, Dirinck E, Verrijken A, Mertens I, Corthouts B, et al. Not performing an OGTT results in significant under diagnosis of (pre) diabetes in a high risk adult Caucasian population. Int. J. Obes. 2005;2017(41):1615–20.

Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Hanley AJG, Rewers MJ, Karter AJ, Haffner SM. A1C between 5.7 and 6.4% as a marker for identifying pre-diabetes, insulin sensitivity and secretion, and cardiovascular risk factors: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (IRAS). Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2104.

World Health Organization. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: abbreviated report of a WHO consultation [Internet]. Geneva; 2011. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/report-hba1c_2011.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2017.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes prevention study: a 20-year follow-up study. The Lancet. 2008;371:1783–9.

Bergenstal RM, Gal RL, Connor CG, Gubitosi-Klug R, Kruger D, Olson BA, et al. Racial differences in the relationship of glucose concentrations and hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:95–102.

Carson AP, Muntner P, Selvin E, Carnethon MR, Li X, Gross MD, et al. Do glycemic marker levels vary by race? Differing results from a cross-sectional analysis of individuals with and without diagnosed diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4:e000213.

Fathallah N, Slim R, Larif S, Hmouda H, Ben Salem C. Drug-induced hyperglycaemia and diabetes. Drug Saf. 2015;38:1153–68.

Balion CM, Raina PS, Gerstein HC, Santaguida PL, Morrison KM, Booker L, et al. Reproducibility of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) classification: a systematic review. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1180–5.

Wallander M, Malmberg K, Norhammar A, Rydén L, Tenerz Å. Oral glucose tolerance test: a reliable tool for early detection of glucose abnormalities in patients with acute myocardial infarction in clinical practice. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:36–8.

Gyberg V, De Bacquer D, Kotseva K, De Backer G, Schnell O, Tuomilehto J, et al. Time-saving screening for diabetes in patients with coronary artery disease: a report from EUROASPIRE IV. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013835.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: BS, VG, DDB, LR; acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and approval for submission: All authors; drafting of the manuscript: BS, DDB, LR; critical revision of the manuscript: All authors; statistical analysis: DDB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The EUROASPIRE Study Group is grateful to the administrative staff, physicians, nurses, and other personnel in the primary care centers in which the survey was carried out and to all patients who participated in the surveys.

Competing interests

B.S., D.D.B., G.D.B, DW. and O.S. have nothing to declare. V.G. reports grants from Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and from European Society of Cardiology during the conduct of the study and lecture honorarium from MSD Sweden and Astra Zeneca Sweden outside the submitted work. L.R. reports grants from The Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and The European Society of Cardiology. K.K. reports grants from European Society of Cardiology. J.T. reports grants from Bayer Pharma and Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and fees from Merck Serono, personal fees from Orion Pharma and Renova outside the submitted work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

National Co-ordinators were responsible for obtaining Local Research Ethics Committees approvals. Written, informed consent was obtained from each participant by the investigator by a signed declaration. The research assistants signed the Case Record Form confirming that informed consent was obtained. The original signed declaration was stored in the patient file.

Funding

The survey was carried out under the auspices of the EURObservational Research Programme of the European Society of Cardiology and was supported through unrestricted research Grants to the European Society of Cardiology from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glaxo-SmithKline, F. Hoffman-La Roche and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The equipment for glucose measurement was provided free of charge by the HemoCue® Company, Ängelholm, Sweden. The sponsors of the EUROASPIRE surveys had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of this report. All authors had access to data, approved the manuscript and the submission for publication. Professor Lars Rydén is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahim, B., Gyberg, V., De Bacquer, D. et al. Undetected dysglycaemia common in primary care patients treated for hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia: on the need for a screening strategy in clinical practice. A report from EUROASPIRE IV a registry from the EuroObservational Research Programme of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0665-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0665-4