Abstract

Background

Cigar use among adults in the United States has remained relatively stable in the past decade and occupies a growing part of the tobacco marketplace as cigarette use has declined. While studies have established the detrimental respiratory health effects of cigarette use, the effects of cigar use need further characterization. In this study, we evaluate the prospective association between cigar use, with or without cigarettes, and asthma exacerbation.

Methods

We used data from Waves 1–5 (2013–2019) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study to run generalized estimating equation models examining the association between time-varying, one-wave-lagged cigarette and cigar use and self-reported asthma exacerbation among US adults (18+). We defined our exposure as non-established (reference), former, exclusive cigarette, exclusive cigar, and dual use. We defined an asthma exacerbation event as a reported asthma attack in the past 12 months necessitating oral or injected steroid medication or asthma symptoms disrupting sleep at least once a week in the past 30 days. We adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, household income, health insurance, established electronic nicotine delivery systems use, cigarette pack-years, secondhand smoke exposure, obesity, and baseline asthma exacerbation.

Results

Exclusive cigarette use (incidence rate ratio (IRR): 1.26, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.03–1.54) and dual use (IRR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.08–1.85) were associated with a higher rate of asthma exacerbation compared to non-established use, while former use (IRR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.80–1.28) and exclusive cigar use (IRR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.42–1.17) were not.

Conclusion

We found no association between exclusive cigar use and self-reported asthma exacerbation. However, exclusive cigarette use and dual cigarette and cigar use were associated with higher incidence rates of self-reported asthma exacerbation compared to non-established use. Studies should evaluate strategies to improve cigarette and cigar smoking cessation among adults with asthma who continue to smoke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways that impacted over 20 million adults in the United States (US) in 2021 [1, 2]. Clinical management of asthma has improved considerably over time, but many people continue to experience asthma exacerbations [3,4,5,6]. Asthma exacerbations are the worsening of asthma symptoms (e.g., increase in coughing or nocturnal coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness) and deterioration of lung function requiring a change in treatment [7, 8]. In 2021, nearly 40% of adults with asthma in the US experienced at least one asthma attack in the preceding 12 months [2]. Asthma exacerbations are associated with downstream health impacts, including decreased quality of life [9], decreased employment [10], and increased healthcare spending [11, 12]. Several individual-level (e.g., demographic, behavior, genetic, health), and environmental (e.g., allergens, infections, pollution) risk factors are associated with increased asthma exacerbations among adults, including combustible tobacco product use such as cigarettes [7, 8, 13,14,15,16].

From 2015 to 2021, prevalence of adults in the US who smoked cigarettes every day or some days decreased from 15.1% to 11.5% [17, 18]. However, cigarette use remains an important risk factor for asthma exacerbation. The 2014 Surgeon General’s report concluded, “The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between active smoking and exacerbation of asthma in adults.” [19] Studies have found an association between cigarette use and asthma exacerbations requiring healthcare visits (e.g. unscheduled physician visit, emergency department visit, hospitalization) [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], necessitating medication (e.g. corticosteroids) [22, 29, 30], or comprising of severe symptoms and frequent attacks [22, 31]. While the evidence showing the negative impact of cigarette use on asthma exacerbation is robust, less is known about the potential risks of asthma exacerbation attributable to cigar use or dual use of cigarettes and cigars.

Unlike cigarette use, prevalence of cigar use among adults in the US has remained relatively stable, hardly changing from 3.4% in 2015 to 3.5% in 2021 [17, 18]. A recent study found no association between cigar use and new onset or worsening asthma [32]. However, the association between cigar use and asthma or asthma exacerbation remains unclear; studies that examined these associations have limited sample size, inconsistent outcomes, and combined cigars with other tobacco products like pipes [33]. Still, adults who use cigars are exposed to nicotine and many of the same addictive, toxic, and carcinogenic constituents found in cigarettes [33, 34]. Even people who do not actively inhale cigar smoke are exposed to the high levels of environmental tobacco smoke that cigars produce [34]. Furthermore, cigarette and cigar use are intertwined; among adults who smoked non-premium cigars, more than half also smoked cigarettes [35]. Yet, we are unaware of any studies that have examined the association of dual use of cigarettes and cigars with asthma exacerbation.

Additional prospective studies and more clarity regarding the relationship between cigar use and asthma exacerbation are needed. In this study, we investigated the prospective association of self-reported asthma exacerbation by cigarette and cigar use status among a nationally representative sample of adults with asthma in the US.

Methods

Data

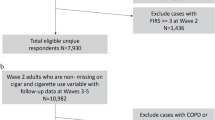

We used restricted adult (18+) data from Waves 1–5 (2013–2019) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, an ongoing, nationally representative longitudinal cohort study of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population. Information about the PATH study design and how to access restricted PATH data files can be found elsewhere [36, 37]. In this study, our analytic sample consisted of 2,883 adult respondents previously diagnosed with asthma at baseline (Wave 1) who participated in at least one follow-up wave (Waves 2–5) and provided complete information related to the exposure, covariates, and outcome (Fig. 1). Our study was considered not regulated by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board due to the use of secondary, de-identified data.

Measure for asthma exacerbation

We used two questions to create a dichotomous variable indicating whether respondents experienced an asthma exacerbation at each follow-up wave. Respondents with an asthma diagnosis in Waves 3–5 were asked, “In the past 12 months, have you had an asthma attack that required the use of an oral or injected steroid medication at the time of the attack?” Notably, only respondents with asthma who also regularly used an oral or injected steroid medication in the past 12 months were asked the same question in Wave 2. From Waves 2–5, respondents with asthma were also asked, “In the past 30 days, how often did your asthma symptoms (such as wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, or pain) wake you up at night or earlier than usual in the morning?” We considered respondents to have had an asthma exacerbation at each follow-up wave if they indicated using steroid medication for an asthma attack in the past 12 months or reported waking up at least one time per week in the past 30 days due to asthma symptoms.

Measure for cigarettes and cigars use

We defined current cigarette use as having smoked cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days, established cigarette use as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime, and experimental cigarette use as having smoked cigarettes, but less than 100 in a lifetime. For cigars, we combined three cigar products – traditional cigars, cigarillos, and filtered cigars – and defined current cigar use as having used any cigar products at least once in the past 30 days, established cigar use as having used any cigar products fairly regularly, and experimental cigar use as having used any cigar product, but none fairly regularly.

Based on these definitions, we constructed an exposure variable at each wave with five categories: (1) never, former experimental, or experimental use [non-established cigarette and cigar use], (2) former established use of cigarettes or cigars [former cigarette or cigar use], (3) exclusive current established cigarette use [exclusive cigarette use], (4) exclusive current established cigar use [exclusive cigar use], and (5) current established dual use [dual use]. We then included this variable in our models as a time-varying exposure and lagged it by one wave to ensure the exposure temporally preceded the outcome. Our reference group was respondents who had never used cigarettes or cigars or had only experimented (formerly or currently) with either product.

Covariates

We included age (continuous), sex (female, male), race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, another NH race and ethnicity), annual household income ($50,000 or more, less than $50,000), and health insurance status (covered, not covered) as baseline sociodemographic covariates. We also adjusted for tobacco-related risk factors, including time-varying electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use and baseline cigarette pack-years. For time-varying ENDS use, we created a three-category (never or experimental use [non-established ENDS use], former established ENDS use [former ENDS use], current established ENDS use [current ENDS use]) variable, where ever fairly regular ENDS use was defined as established ENDS use and ENDS use at least once in the past 30 days was defined as current ENDS use. We calculated cigarette pack-years by multiplying the average number of packs-per-day and the years respondents smoked cigarettes to account for cigarette smoking history. Additionally, we controlled for other asthma exacerbation risk factors, including time-varying secondhand smoke exposure (number of 12-hour periods spent in close contact with others who were smoking in the past seven days), obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30.0) at baseline, and a prior asthma exacerbation at baseline (had an asthma attack in the past 12 months that required the use of an oral or injected steroid medication).

Statistical analyses

We calculated weighted descriptive statistics to describe the overall analytic sample, respondents’ tobacco use behavior by cigarette and cigar use status at baseline, and the number of follow-up waves respondents experienced asthma exacerbations. Using an unbalanced person-period dataset, we ran generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to evaluate the prospective association between cigarette and cigar use and asthma exacerbation over three 1-year periods (Wave 1 – Wave 2, Wave 2 – Wave 3, Wave 3 – Wave 4) and one 2-year period (Wave 4 – Wave 5). For these models, we specified unstructured covariance, within-person correlation matrices, and a negative binomial distribution of the dependent variable using a log link function to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

We excluded respondents who were missing exposure, covariate, or outcome information from the analytic sample and did not use any multiple imputation techniques. Literature examining complete case and multiple imputation analyses indicates that multiple imputation is more effective than complete case analysis when at least 5% to 10% of the data is missing [38, 39]. In our analysis, missingness ranged from 0.1% to 5.5% across covariates (Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, baseline characteristics of the analytic sample and the sample not excluding respondents with missing information were very similar, limiting concerns about missing data.

We weighted all data using Wave 1 weights to ensure that it was representative of the US civilian, non-institutionalized adult population at baseline, and we estimated variance using balanced repeated replication methods with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 [40]. We calculated descriptive statistics using Stata software, version 18.0 [41], and ran the weighted GEE analysis using modified code developed by Kasza et al. [42] with SAS V9.4 software [43].

Sensitivity analyses

We ran multiple sensitivity analyses to confirm the robustness of our findings. First, we restricted the analysis to Waves 1–4 to examine how Wave 5 data impacted our results. Unlike earlier waves when PATH collected data annually, PATH began collecting data biennially with Wave 5, resulting in a two-year gap between Waves 4 and 5. Second, we re-ran the analysis using different weights to account for changes in non-response and eligibility across the waves. We used Wave 2 “single-wave” weights to restrict the analysis to respondents who participated in at least Waves 1 and 2 and Wave 5 “all-waves” weights to restrict the analysis to respondents who participated in all five follow-up waves. Third, we excluded respondents previously diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at baseline following recommendations made in a study that examined the association between different tobacco product use and asthma [32]. We further replicated that study’s approach [32] and ran another analysis excluding respondents previously diagnosed with COPD, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or some other lung or respiratory condition at baseline. Fourth, we excluded respondents from the analysis who exclusively smoked premium traditional cigars at baseline because they potentially misrepresented true established cigar use. A report on premium traditional cigars from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) found differences in how premium traditional cigars are used compared to other cigar products [33]. People who smoked premium traditional cigars had lower frequency and intensity of smoking, were less likely to smoke cigarettes or other cigar products concurrently, and were more likely to be never or former cigarette smokers than those who used other cigar products [33]. Using previously described methods, we defined premium cigars based on brand name and price [33]. Fifth, we adjusted for other combustible tobacco products, hookah and pipe tobacco. For each product, we defined ever fairly regular use as established use and any past 30 day use as current use to create time-varying, three-category variables (never or experimental use, former established use, and current established use) indicating use status. Sixth, we adjusted for time-varying annual household income, time-varying health insurance status, and time-varying obesity rather than baseline values to capture potential changes over time. Lastly, we disaggregated the ‘non-established use’ category to create a seven-category exposure variable and changed the reference group to only respondents who had never used cigarettes or cigars.

Results

Sample demographics

At baseline, the mean age of our analytic sample of adults with an asthma diagnosis was 44.4 years (standard deviation (SD) = 17.4 years) (Table 1). They were predominantly female (61.7%), NH White (67.7%), had annual household incomes less than $50,000 (59.4%), and had health care coverage (90.0%). The average cigarette pack-years among sample respondents was 6.5 (SD = 15.1) and the average number of hours they were exposed to secondhand smoke in the past seven days was 7.3 h (SD = 21.6 h). Over 40% of respondents had a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 (41.7%) and 15.4% had had an asthma exacerbation. Most respondents had non-established ENDS use, but 1.5% formerly used ENDS, and 2.4% currently used ENDS. Lastly, 60.5% of respondents had non-established cigarette or cigar use at baseline, 20.7% formerly smoked cigarettes or cigars, 16.5% exclusively used cigarettes, 1.0% exclusively used cigars, and 1.3% dual used cigarettes and cigars.

Tobacco use behavior

Established, current use of cigarettes and cigars remained consistent across Waves 1–4 (Supplemental Table 2). Generally, respondents who dual used cigarettes and cigars were more similar to those who exclusively smoked cigarettes than those who exclusively smoked cigars at baseline (Table 2). Specifically, both groups had a similar mean number of days they used cigarettes in the past 30 days (exclusive cigarettes: 26.8 days, dual use: 27.5 days), mean number of hours they were exposed to secondhand smoke in the past seven days (exclusive cigarettes: 22.5 h, dual use: 26.3 h), and cigarette smoking history (exclusive cigarettes: 16.2 pack-years, dual use: 15.8 pack-years). In contrast, respondents who exclusively smoked cigars smoked cigarettes experimentally an average of 7.8 days in the past 30 days, were exposed to secondhand smoke an average of 15.1 h in the past seven days, and averaged 4.0 pack-years of cigarette smoking. Respondents who exclusively used cigars or dual used cigarettes and cigars both used filtered cigars an average of 5.6 days in the past 30 days, but there were slight differences in the average number of days these respondents used cigarillos (exclusive cigars: 6.4 days, dual use: 5.2 days) and traditional cigars (exclusive cigars: 3.2 days, dual use: 4.2 days) in the past 30 days. Lastly, respondents who formerly smoked cigarettes or cigars had the highest number of cigarette pack-years (17.3 pack-years) but were otherwise similar to respondents with non-established cigarette or cigar use.

Asthma exacerbation events

In the four follow-up waves examined, most respondents (64.2%) did not experience an asthma exacerbation event (Table 3). Nearly half of all respondents who experienced an asthma exacerbation event in at least one wave (n = 1,018) had an asthma exacerbation event in two or more waves. Overall, 18.7% had an asthma exacerbation event in one wave, 8.3% in two, 5.8% in three, and 3.0% in four waves.

Association between cigarette and cigar use and asthma exacerbation

In the unadjusted GEE model, respondents who exclusively smoked cigarettes (IRR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.26–1.82) or dual used cigarettes and cigars (IRR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.31–2.24) had higher rates of asthma exacerbation compared to those who had non-established cigarette and cigar use (Table 4, Model 1). The rate of asthma exacerbation for respondents who formerly smoked cigarettes or cigars (IRR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.00–1.46) or exclusively smoked cigars (IRR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.44–1.20) did not differ statistically from the rate for respondents with non-established use. Adjusting for baseline sociodemographic, tobacco use history, and other asthma exacerbation risk factors (Table 4, Model 4) attenuated the estimated IRRs but did not change the statistical significance of the findings. Exclusive cigarette use (IRR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.03–1.54) and dual use (IRR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.08–1.85) had higher rates of asthma exacerbation, whereas former use of either product (IRR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.80–1.28) and exclusive cigar use (IRR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.42–1.17) did not differ statistically from non-established use of either product. Also of note, in the final adjusted model, respondents with current ENDS use had higher rates of asthma exacerbation (IRR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.02–1.40) than respondents who had non-established ENDS use.

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses were consistent with our main findings (Supplemental Tables 3–11). Notably, the association found between current ENDS use and asthma exacerbation was no longer statistically significant except in the sensitivity analyses using Wave 2 “single-wave” weights (Supplemental Table 4), adjusting for hookah and pipe tobacco use (Supplemental Table 9), adjusting for time-varying annual household income, health insurance status, and obesity (Supplemental Table 10), and using the exposure variable disaggregating non-established use (Supplemental Table 11).

Discussion

We examined the prospective association of cigarette and cigar use with asthma exacerbation incidence among US adults using nationally representative data from PATH Waves 1–5 (2013–2019) and adjusting for baseline sociodemographic, tobacco use history, and other asthma exacerbation risk factors. We found that exclusive cigarette use and dual use of cigarettes and cigars were both associated with higher rates of asthma exacerbation compared to non-established use of either product. We consistently detected these associations across a series of sensitivity analyses. However, we found no statistically significant association for former cigarette or cigar use, nor for exclusive cigar use in the five-year follow-up period.

Our findings regarding the impact of cigarette use on asthma exacerbation align with those from past studies that found an association between current cigarette use and higher rates of asthma exacerbation [19]. A recent study that assessed the influence of active tobacco smoking on asthma outcomes found asthmatic patients who currently smoked cigarettes had twice the mean number of asthma exacerbations per year as patients who never smoked cigarettes and patients who formerly smoked cigarettes [30]. Adults with asthma who smoke cigarettes have a greater decline in lung function, worse asthma severity, less control over asthma symptoms, increased rates of hospitalization, attenuated response to corticosteroids, greater need for rescue medications, and higher morbidity and mortality rates than those with asthma who do not smoke cigarettes [44, 45]. However, prevalence of cigarette use among adults with asthma is similar to the general population [45, 46]. We found no association between former cigarette or cigar use and asthma exacerbation incidence, suggesting that smoking cessation may be a necessary and effective method to decrease asthma exacerbations.

Our study adds to the growing literature examining the health impacts of cigar use and dual use with cigarettes. Cigar product use is heterogeneous, ranging from premium traditional cigars that are smoked occasionally to filtered cigars that are smoked more frequently [35]. Adding further complexity, cigar use appears to be more unstable than cigarette use and how cigar products are used depends on past cigarette use [33, 47]. We found no association between exclusive cigar use and asthma exacerbation, but dual use of cigarettes and cigars was associated with higher rates of asthma exacerbation compared to non-established use. This is consistent with our observation that adults with asthma who used both products were more similar to adults who exclusively smoked cigarettes than those who exclusively smoked cigars in terms of tobacco use behavior and history at baseline. Our findings further suggest that adults who dual use may have higher rates of asthma exacerbation incidence than adults who exclusively use cigarettes. Inhalation of cigar smoke, known to be associated with adverse health effects [33, 34], is a likely explanation if these findings can be confirmed. Prior research has found that adults who smoke cigars are more likely to inhale if they ever smoked cigarettes than if they never smoked cigarettes [33, 34]. Furthermore, people who dual use cigarettes and cigars are more likely to smoke cigars with greater intensity and inhale smoke more intensely than people who exclusively smoke cigars [33, 34].

In our final model, we also adjusted for ENDS use. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among US adults has steadily increased from 3.5% in 2015 to 4.5% in 2021 [17, 18]. Multiple studies examining the acute respiratory effects of ENDS use found that short-term ENDS use decreased pulmonary functions and increased airway inflammation among individuals with asthma [48,49,50,51], but at least one study did not [52]. We found that current ENDS use was associated with higher rates of asthma exacerbation compared to non-established ENDS use. However, in several sensitivity analyses, this association was no longer statistically significant. The evidence for an association between ENDS use and asthma exacerbation in the literature is inconclusive [53], with some studies finding an association [54,55,56] and others not [32, 57]. Further research is needed before any conclusions can be drawn because data examining the long-term health effects of ENDS use are limited [53]. As more data becomes available and items measuring ENDS use are standardized, studies should also consider assessing what impact, if any, ENDS initiation, duration of use, frequency or intensity of use, device type, and flavoring have on asthma and other respiratory disease outcomes. For now, even if ENDS are safer alternatives to combustible tobacco products, researchers and clinicians should be cautious when advocating for ENDS use as a smoking cessation method for adults with asthma. ENDS aerosols are still poorly characterized, long-term health impacts are unknown, and airway alterations may place adults with asthma at higher risk for complications.

Our study has several strengths. First, we build upon growing literature examining the impact of multiple tobacco product use on asthma exacerbation [32, 56]. Second, we used prospective, nationally representative data from the PATH Study increasing the generalizability of our findings. Third, we corroborated our findings by conducting rigorous sensitivity analyses that considered multiple weighting schemes and additional adjustments. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the only study to date that has prospectively evaluated the impact of dual cigarette and cigar use on asthma exacerbation.

However, some limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, we used self-reported measures which are subject to response biases. Social desirability may also have led to underreporting of tobacco use due to potential stigma against adults with asthma who continue to use combustible tobacco products. Still, this would have biased our results towards the null and supported the robustness of our findings. Second, we aggregated traditional cigars, cigarillos, and filtered cigars due to sample size concerns (n = 56 for exclusive current established any cigar use at baseline) and were therefore unable to examine asthma exacerbation risk associated with individual cigar product types alone or combined with cigarettes, which may be important given the variation in both the frequency and intensity of use across product types. Future studies should recruit larger samples of adults who smoke cigars to garner sufficient power needed to evaluate the risk posed by different cigar types. Third, our analysis was limited to the data that was collected in the PATH Study. We were unable to adjust for important asthma exacerbation risk factors, such as allergies or atopies, viral upper respiratory tract infections, and environmental air pollution [7, 13, 14], which may have confounded our analysis. Furthermore, we were unable to account for the level of cigar smoke inhalation and we could not examine the frequency and severity of asthma exacerbations.

Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that time-varying exclusive cigarette use and dual use of cigarettes and cigars were associated with higher asthma exacerbation rates compared to non-established use of cigarettes and cigars among US adults with asthma using nationally representative data. Neither time-varying former cigarette or cigar use, nor exclusive cigar use were statistically associated with asthma exacerbation. There is a need to develop more effective smoking cessation interventions for adults with asthma who continue using combustible tobacco products, especially those who dual use. Additionally, as the tobacco marketplace changes and new policies are implemented, further studies will be needed to better understand how tobacco products like cigars and ENDS are associated with asthma exacerbation risk and their impact on the frequency and severity of asthma exacerbations.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed in the current study used restricted use data from the PATH Study because the analysis included cigarette pack-years and continuous age. Details on how to access restricted use data from the PATH Study is described in the PATH Study Restricted Use Files User Guide: https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36231.v37. Researchers interested in obtaining these data from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan must complete a Restricted Data Use Agreement. For additional information, please reference: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/pages/NAHDAP/vde/index.html.

Abbreviations

- US:

-

United States

- PATH:

-

Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health

- NH:

-

Non–Hispanic

- ENDS:

-

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- GEE:

-

Generalized Estimating Equation

- IRR:

-

Incidence Rate Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- NASEM:

-

National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

US Department of Health and Human Services: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3 2007). NIH Item No. 08-4051. 2007.

Most Recent National Asthma Data. [https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm]

Chu EK, Drazen JM. Asthma: one hundred years of treatment and onward. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1202–8.

Miller RL, Grayson MH, Strothman K. Advances in asthma: New understandings of Asthma’s natural history, risk factors, underlying mechanisms, and clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:1430–41.

O’Byrne PM, Jenkins C, Bateman ED. The paradoxes of asthma management: time for a new approach? Eur Respir J 2017, 50.

Ramsahai JM, Hansbro PM, Wark PAB. Mechanisms and management of Asthma exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:423–32.

Global Initiative for Asthma: Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2023. 2023.

Bourdin A, Bjermer L, Brightling C, Brusselle GG, Chanez P, Chung KF, Custovic A, Diamant Z, Diver S, Djukanovic R et al. ERS/EAACI statement on severe exacerbations in asthma in adults: facts, priorities and key research questions. Eur Respir J 2019, 54.

Luskin AT, Chipps BE, Rasouliyan L, Miller DP, Haselkorn T, Dorenbaum A. Impact of asthma exacerbations and asthma triggers on asthma-related quality of life in patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:544–e552541.

Song HJ, Blake KV, Wilson DL, Winterstein AG, Park H. Medical costs and Productivity loss due to mild, moderate, and severe asthma in the United States. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;13:545–55.

Ivanova JI, Bergman R, Birnbaum HG, Colice GL, Silverman RA, McLaurin K. Effect of asthma exacerbations on health care costs among asthmatic patients with moderate and severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1229–35.

Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, Albers FC. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:74.

Dougherty RH, Fahy JV. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:193–202.

Greenberg S. Asthma exacerbations: predisposing factors and prediction rules. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:225–36.

Greenblatt RE, Zhao EJ, Henrickson SE, Apter AJ, Hubbard RA, Himes BE. Factors associated with exacerbations among adults with asthma according to electronic health record data. Asthma Res Pract. 2019;5:1.

Eisner MD. Environmental tobacco smoke and adult asthma. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:749–61.

Phillips E, Wang TW, Husten CG, Corey CG, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, Homa DM, King BA. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1209.

Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A, Lynn BCD, Mayer M, Alcantara IC, Neff L. Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:475.

US Department of Health Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA, USA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

Silverman RA, Boudreaux ED, Woodruff PG, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr, Investigators MARC. Cigarette smoking among asthmatic adults presenting to 64 emergency departments. Chest. 2003;123:1472–9.

Eisner MD, Iribarren C. The influence of cigarette smoking on adult asthma outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:53–6.

Strine TW, Balluz LS, Ford ES. The associations between smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, and asthma severity in the general US population. J Asthma. 2007;44:651–8.

Boulet L-P, FitzGerald JM, McIvor RA, Zimmerman S, Chapman KR. Influence of current or former smoking on asthma management and control. Can Respir J. 2008;15:275–9.

Kauppi P, Kupiainen H, Lindqvist A, Haahtela T, Laitinen T. Long-term smoking increases the need for acute care among asthma patients: a case control study. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:1–9.

Colak Y, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG, Lange P. Characteristics and prognosis of never-smokers and smokers with asthma in the Copenhagen General Population Study. A prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:172–81.

Khokhawalla SA, Rosenthal SR, Pearlman DN, Triche EW. Cigarette smoking and emergency care utilization among asthmatic adults in the 2011 asthma call-back survey. J Asthma. 2015;52:732–9.

Bittner JC, Hasegawa K, Probst BD, Mould-Millman NK, Silverman RA, Camargo CA Jr. Smoking status and smoking cessation intervention among U.S. adults hospitalized for asthma exacerbation. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37:318–23.

Silverman RA, Hasegawa K, Egan DJ, Stiffler KA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter study of cigarette smoking among adults with asthma exacerbations in the emergency department, 2011–2012. Respir Med. 2017;125:89–91.

Thomson NC, Chaudhuri R, Heaney LG, Bucknall C, Niven RM, Brightling CE, Menzies-Gow AN, Mansur AH, McSharry C. Clinical outcomes and inflammatory biomarkers in current smokers and exsmokers with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1008–16.

Tiotiu A, Ioan I, Wirth N, Romero-Fernandez R, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ. The impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18.

Siroux V, Pin I, Oryszczyn M, Le Moual N, Kauffmann F. Relationships of active smoking to asthma and asthma severity in the EGEA study. Epidemiological study on the Genetics and Environment of Asthma. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:470–7.

Brunette MF, Halenar MJ, Edwards KC, Taylor KA, Emond JA, Tanski SE, Woloshin S, Paulin LM, Hyland A, Lauten K et al. Association between tobacco product use and asthma among US adults from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study waves 2–4. BMJ Open Respir Res 2023, 10.

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Premium cigars: patterns of use, marketing, and health effects. Washington, DC: National Academies; 2022.

National Cancer Institute. Cigars: Health effects and trends. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9. Bethesda. Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1998.

Corey CG, Holder-Hayes E, Nguyen AB, Delnevo CD, Rostron BL, Bansal-Travers M, Kimmel HL, Koblitz A, Lambert E, Pearson JL, et al. US Adult Cigar Smoking Patterns, Purchasing behaviors, and reasons for Use according to cigar type: findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, 2013–2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;20:1457–66.

Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, Taylor K, Crosse S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Tob Control. 2017;26:371–8.

United States Department of Health Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, United States Department of Health Human Services. Food Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products: Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study [United States] restricted-use files. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2023.

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials - a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:162.

Langkamp DL, Lehman A, Lemeshow S. Techniques for handling missing data in secondary analyses of large surveys. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:205–10.

Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. J Official Stat. 1990;6:223–39.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18., 18.0 edition. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2023.

Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Tang Z, Stanton CA, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, Taylor KA, Donaldson E, Hull LC, Day H, et al. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control. 2020;29:s191–202.

SAS. SAS 9.4 Software. 9.4M6 edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2018.

Polosa R, Thomson NC. Smoking and asthma: dangerous liaisons. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:716–26.

Bellou V, Gogali A, Kostikas K. Asthma and Tobacco Smoking. J Pers Med 2022, 12.

Thomson NC, Polosa R, Sin DD. Cigarette smoking and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2783–97.

Jeon J, Mok Y, Meza R. Cross-sectional patterns and longitudinal transitions of Premium and Non-premium Cigar Use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023;25:S16–23.

Vardavas CI, Anagnostopoulos N, Kougias M, Evangelopoulou V, Connolly GN, Behrakis PK. Short-term pulmonary effects of using an electronic cigarette: impact on respiratory flow resistance, impedance, and exhaled nitric oxide. Chest. 2012;141:1400–6.

Palamidas A, Tsikrika S, Katsaounou PA, Vakali S, Gennimata SA, Kaltsakas G, Gratziou C, Koulouris N. Acute effects of short term use of ecigarettes on airways physiology and respiratory symptoms in smokers with and without Airway Obstructive Diseases and in Healthy non smokers. Tob Prev Cessat. 2017;3:5.

Lappas AS, Tzortzi AS, Konstantinidi EM, Teloniatis SI, Tzavara CK, Gennimata SA, Koulouris NG, Behrakis PK. Short-term respiratory effects of e-cigarettes in healthy individuals and smokers with asthma. Respirology. 2018;23:291–7.

Kotoulas SC, Pataka A, Domvri K, Spyratos D, Katsaounou P, Porpodis K, Fouka E, Markopoulou A, Passa-Fekete K, Grigoriou I, et al. Acute effects of e-cigarette vaping on pulmonary function and airway inflammation in healthy individuals and in patients with asthma. Respirology. 2020;25:1037–45.

Boulay ME, Henry C, Bosse Y, Boulet LP, Morissette MC. Acute effects of nicotine-free and flavour-free electronic cigarette use on lung functions in healthy and asthmatic individuals. Respir Res. 2017;18:33.

Kotoulas SC, Katsaounou P, Riha R, Grigoriou I, Papakosta D, Spyratos D, Porpodis K, Domvri K, Pataka A. Electronic cigarettes and asthma: what do we know so far? J Pers Med 2021, 11.

Entwistle MR, Valle K, Schweizer D, Cisneros R. Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use and frequency of asthma symptoms in adult asthmatics in California. J Asthma. 2021;58:1460–6.

Lee SY, Shin J. Association between Electronic cigarettes Use and Asthma in the United States: data from the National Health interview Survey 2016–2019. Yonsei Med J. 2023;64:54–65.

Balan I, Mahmood SN, Jaiswal R, Pleshkova Y, Manivannan D, Negit S, Shah V, Desai P, Akula NV, Nawaz MU, et al. Prevalence of active and passive smoking among asthma and asthma-associated emergency admissions: a nationwide prevalence survey study. J Investig Med. 2023;71:730–41.

Chaffee BW, Barrington-Trimis J, Liu F, Wu R, McConnell R, Krishnan-Sarin S, Leventhal AM, Kong G. E-cigarette use and adverse respiratory symptoms among adolescents and Young adults in the United States. Prev Med. 2021;153:106766.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under Award Number U54CA229974. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NLF obtained funding for the study. NLF and JHB supervised the completion of the study. NLF and JHB conceptualized and designed the study. AP, JHB, and NLF acquired, planned, and interpreted the data. AP completed the data analysis. AP drafted the manuscript. AP, JHB, SC, DAA, and NLF critically revised, edited, and gave final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved publication of this version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The PATH Study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. All adult respondents (age 18+) in the PATH Study provided informed consent. This study was considered not regulated by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board since only secondary, de-identified data was utilized.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this work are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Health and Human Services, nor the United States government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, A., Buszkiewicz, J.H., Cook, S. et al. Longitudinal association of exclusive and dual use of cigarettes and cigars with asthma exacerbation among US adults: a cohort study. Respir Res 25, 305 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-024-02930-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-024-02930-y