Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to identify the underlying genetic defect in a family segregating autosomal recessive asymmetric hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN). Asymmetric HMN has not been associated earlier with SORD mutations.

Methods

For this study, we have recruited a family and collected blood samples from affected and normal individuals of a family. Detailed clinical examination and electrophysiological studies were carried out. Whole exome sequencing was performed to detect the underlying genetic defect in this family. The potential variant was validated using the Sanger sequencing approach.

Results

Clinical and electrophysiological examination revealed asymmetric motor neuropathy with normal nerve conduction velocities and action potentials. Genetic analysis identified a homozygous mononucleotide deletion mutation (c.757delG) in a SORD gene in a patient. This mutation is predicted to cause premature truncation of a protein (p.A253Qfs*27).

Conclusions

Interestingly, the patient with homozygous SORD mutation demonstrates normal motor and nerve conduction velocities and action potentials. The affected individual describes in this study has a unique presentation of asymmetric motor neuropathy predominantly affecting the right side more than the left as supported by the clinical examination. This is the first report of SORD mutation from Saudi Arabia and this study further expands the phenotypic spectrum of SORD mutation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorder affecting the muscles of distal limbs. Individuals with dHMN experience progressive weakness and atrophy of the muscles of the distal limbs [1]. In dHMN, generally, there is no involvement of sensory neurons, however, in some cases minimal involvement of sensory neurons is reported [2]. Based on the inheritance pattern and the clinical features, dHMN has been divided into seven subgroups [3]. Autosomal recessive dHMN may appear early in life with mild as well as severe clinical features. dHMN and Charcot-Mare-Tooth (CMT) diseases are clinically and genetically overlapping disorders and in some cases, they share the underlying genetic defects [4, 5]. For instance, mutations in HSPB1, IGHMBP2, and DYNC1H1 cause both CMT and dHMN [1, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Moreover, mutations in the sorbitol dehydrogenase (SORD) gene have recently been associated with the autosomal recessive form of Charcot-Mare-Tooth disease type 2 (CMT2) and dHMN [1, 8, 16, 17]. Although, a clinical and genetic overlap exists between CMT2 and dHMN, however, motor nerves are predominantly or exclusively involved in dHMN [2].

We recruited a family segregating autosomal recessive dHMN. Clinical and genetic analysis was performed and a homozygous nonsense mutation in the SORD gene (c.757delG; p.Ala253GlnfsTer27) was identified. The mutation has been shown to cause a complete loss of SORD protein resultantly an increased sorbitol level in the cells.

Methods

Ethical approval

All study protocols were approved by the scientific research ethics committee of the College of Medicine, Taibah University Medina. The ethical approval ID is 036-1441. All experimental work was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants for genetic analysis of the DNA samples and publication of the genetic data.

Genetic studies

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of a proband (II:3), unaffected parents (I:1 and I:2), a healthy individual (II:4), and an affected sibling (II:6) (Fig. 1). The complete coding regions (~ 22,000 genes) of the human genome was captured by xGen Exome Research Panel v2 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa, USA). The captured region of the human genome was sequenced with NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The raw sequencing data analysis, including alignment to the GRCh37/hg19 human reference genome, variant calling, and annotation, was conducted with open-source bioinformatics tools and in-house software. A variant interpretation was performed with in-house software to prioritize variants based on ACMG guidelines considering the phenotype of the patient. This system has three major steps; variant filtration, classification, and similarity scoring for patient’s phenotype. The following steps were used to filter and prioritize candidate variants. First, gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) as a population genome database were used for estimating allele frequency. Common variants with a minor allele frequency of > 5% were filtered out in accordance with BA1 of the ACMG guideline. Second, scientific literature and disease databases including ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) were searched and evidence data on the pathogenicity of variants was extracted. The pathogenicity of each variant was evaluated according to the recommendations of the ACMG guideline. Third, the clinical features of the patient were coded as standardized human phenotype ontology terms (https://hpo.jax.org/) and accessed to measure the similarity with each of ~ 7000 rare genetic diseases (https://omim.org/ and https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/index.php). The similarity score was calculated for the patient’s phenotype and the prioritized variants. Finally, medical geneticists manually evaluated the candidate variants and associated diseases. The variant of interest was Sanger sequenced in the proband, both parents, a healthy family member, and an affected sibling (Fig. 1).

Results

Clinical description of the patient

A 26 years old patient (II:3) presented with a history of progressive right leg weakness was examined. Initially, he was diagnosed with a distal myopathy. He has been complaining of right knee pain and limping to the right side after long-distance walks. He was free of any other neurological symptoms including muscle cramping, abnormal twitching, muscle fasciculation, and tingling or numbness. He was examined by a consultant neurologist. Motor nerve conduction (MNC) and sensory nerve conduction (SNC) studies have been performed. Moreover, electromyography (EMG) was also carried out. The proband has informed us about another sibling (II:6) with a similar clinical picture.

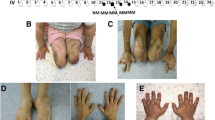

On physical examination, the patient (II:3) was found to have a clear picture of distal neuropathy as evident from a foot deformity, including the common pes cavus, hammer toes, and twisting of the ankle on both sides, more severe on the right side. There was a mild weakness (graded as + 4) on the right foot dorsiflexion and the right ankle reflex was absent. Also, the pinprick and temperature sensation were mildly reduced in the right foot. The posterior column tract examination was intact as well as the gait was within a normal limit (Table 1).

Motor nerve conduction (MNC) studies

Bilateral tibial MNC studies of the abductor halluces revealed a normal distal nerve latency, compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude, and conduction velocity. Moreover, minimal F wave latency was also in the normal range. Right and left peroneal MNC studies recording from the extensor digitorum brevis revealed normal distal motor latency, CMAP amplitude (at 2.3 mV), and conduction velocity. However, comparing the peroneal nerve amplitude of the right side with the left side, the right side amplitude was 50% less than the left side, although, both were within the normal limits.

Sensory nerve conduction (SNC) studies

Bilateral superficial peroneal sensory nerve conduction studies reveal normal peak latencies, sensory nerve action potentials (SNAP) amplitudes, and conduction velocities. Moreover, bilateral sural SNC studies reveal normal peak latencies, SNAP amplitudes and conduction velocities.

Needle electromyography (EMG)

Needle examination of the right first dorsal interosseous (FDIO) space, deltoid and extensor digitorum communis (EDC) revealed normal insertional activity with no spontaneous activity. Motor unit potentials were broad and of high amplitude with a slightly reduced interference pattern. Moreover, the right medial gastrocnemius and left tibialis anterior revealed normal insertional activity. 2 + fibs (fibrillation/positive sharp waves) and positive sharp waves with occasional runs of complex repetitive discharges (CRDs) were observed. The right tibialis anterior, and right vastus lateralis revealed normal insertional activity without any spontaneous activity. The motor unit potentials were of high amplitude (polyphasic) and of broad duration with a slightly reduced interference pattern (Table 2).

Overall it is concluded from the electrophysiological studies that the patient has active denervation in the right lower extremities. His clinical presentation is asymmetrical. In general, the patient has a CMT neurological score of 3 based on the physical and neurophysiological examination [18].

A frameshift variant in the SORD gene was identified

A high-quality exome data with more than 100 × coverage was obtained (Table 3). Exome data analysis including variants annotation, filtration, and prioritization identified a homozygous deletion variant (c.757del) in the SORD gene. CG dinucleotides were found deleted which consequently lead to a frameshift in the protein coding sequence. This frameshift is predicted to cause premature protein truncation. This variant is classified as pathogenic according to the recommendation of the ACMG/AMP guideline.

Sanger validation of variant

DNA of the proband, an affected sibling, both parents as well as an unaffected member of the family was PCR amplified using primer pair flanking SORD variant. The amplicons were sequenced using the Sanger approach. BioEdit sequence alignment tool was used to align the patient sequence reads with the reference sequence. The patient and an affected sibling were found homozygous for the deletion variant. However, both parents were found heterozygous and an unaffected member of the family has a wild-type sequence.

Discussion

dHMN accounted for a small proportion of inherited peripheral neuropathy. Considering the wide phenotypic and genetic heritability the diagnostic rate in dHMN ranges from 14 to 39% [1, 5, 11, 19, 20]. Low diagnostic rate in dHMN indicates the presence of an unidentified mutation in novel candidate genes. Large scale studies are needed to identify new causative mutations which would ultimately help in delineating the molecular mechanism underlying dHMN pathogenesis.

We studied a family segregating dHMN in an autosomal recessive manner. Electrophysiological studies including MNC, SNC, and EMG revealed velocities and amplitudes in the normal range. Clinically patient is showing abnormal features specifically the right side of the body is asymmetrically affected. The proband showed overlapping clinical features of both CMT type 2 and dHMN. However, his neurological phenotype was asymmetrical. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the disease, we performed whole-exome sequencing and identified a homozygous dinucleotide deletion (c.757delG) in the SORD gene. This mutation has recently been reported as the most frequent cause of autosomal recessive hereditary neuropathy [1, 17]. This study supports the hypothesis that the specific SORD mutation (c.757delG) is the most common cause of childhood-onset mild form of the autosomal recessive dHMN. This is the first report of SORD mutation from Saudi Arabia and broadens the mutation continuum of SORD and phenotypic heterogeneity of the dHMN. The specific allele (c.757delG) of SORD is wide spread and has been reported by a group from different populations including Chinese, UK, USA, and Turkey [17, 19,20,21]. This support the notion that this allele is of an ancient origin.

Sorbitol dehydrogenase deficiency with peripheral neuropathy is associated with mutations in the SORD gene. To our knowledge, around 16 bi-allelic mutations in the SORD gene have been identified [16,17,18,19,20]. SORD-related neuropathy has been reported as one of the most frequent causes of autosomal recessive CMT2 and dHMN [17]. The deletion mutation c.757delG (p.A253Qfs*27), identified in this study, is the only reported variant in SORD-related dHMN [16, 17, 21]. An exception is a Chinese patient with dHMN harboring the compound heterozygous c.404 A > G and c.9081 + G > C mutation [22]. Almost all mutations in SORD are predicted to cause loss of function of sorbitol dehydrogenase, which is a key enzyme in sorbitol to fructose conversion. The molecular pathway underlying motor-predominant peripheral neuropathy due to sorbitol dehydrogenase deficiency is not well understood.

Availability of data and materials

The vcf file of a patient containing whole exome sequencing data has been submitted to the European Variation Archive (EVA). The accession number is PRJEB48950 and the link to data is https://www.ebi.ac.uk/eva/?Study-Browser&browserType=sgv.

References

Xie Y, Lin Z, Pakhrin PS, et al. Genetic and clinical features in 24 Chinese distal hereditary motor neuropathy families. Front Neurol. 2020;11:603003.

Rossor AM, Kalmar B, Greensmith L, Reilly MM. The distal hereditary motor neuropathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2012;83:6–14.

Harding AE. Inherited neuronal atrophy and degeneration predominantly of lower motor neurons. Fourth ed: Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005.

Laura M, Pipis M, Rossor AM, Reilly MM. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and related disorders: an evolving landscape. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32:641–50.

Bansagi B, Griffin H, Whittaker RG, Antoniadi T, Evangelista T, Miller J, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of motor neuropathies. Neurology. 2017;88:1226–34.

Argente-Escrig H, Sánchez-Monteagudo A, Frasquet M, et al. A very mild phenotype of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4H caused by two novel mutations in FGD4. J Neurol Sci. 2019;402:156–61.

Becker LL, Dafsari HS, Schallner J, et al. The clinical-phenotype continuum in DYNC1H1-related disorders-genomic profiling and proposal for a novel classification. J Hum Genet. 2020;65:1003–17.

Frasquet M, Rojas-García R, Argente-Escrig H, et al. Distal hereditary motor neuropathies: mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:1334–43.

Taga A, Cornblath DR. A novel HSPB1 mutation associated with a late onset CMT2 phenotype: case presentation and systematic review of the literature. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2020;25:223–9.

Muranova LK, Sudnitsyna MV, Strelkov SV, Gusev NB. Mutations in HspB1 and hereditary neuropathies. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;25:655–65.

Cortese A, Wilcox JE, Polke JM, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing panels in the diagnosis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurology. 2020;94:e51-61.

Cassini TA, Duncan L, Rives LC, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals novel IGHMBP2 variant leading to unique cryptic splice-site and Charcot-Marie-Tooth phenotype with early onset symptoms. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e00676.

Kulshrestha R, Forrester N, Antoniadi T, Willis T, Sethuraman SK, Samuels M. Charcot Marie Tooth disease type 2S with late onset diaphragmatic weakness: an atypical case. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28:1016–21.

Dohrn MF, Glöckle N, Mulahasanovic L, et al. Frequent genes in rare diseases: panel-based next generation sequencing to disclose causal mutations in hereditary neuropathies. J Neurochem. 2017;143:507–22.

Beecroft SJ, McLean CA, Delatycki MB, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of DYNC1H1. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27:607–15.

Yuan RY, Ye ZL, Zhang XR, Xu LQ, He J. Evaluation of SORD mutations as a novel cause of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8:266–70.

Cortese A, Zhu Y, Rebelo AP, et al. Biallelic mutations in SORD cause a common and potentially treatable hereditary neuropathy with implications for diabetes. Nat Genet. 2020;52:473–81.

Murphy SM, Herrmann DN, McDermott MP, Scherer SS, Shy ME, Reilly MM, Pareyson D. Reliability of the CMT neuropathy score (second version) in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16:191–8.

Liu X, Duan X, Zhang Y, Sun A, Fan D. Molecular analysis and clinical diversity of distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1319–26.

Liu X, He J, Yilihamu M, Duan X, Fan D. Clinical and genetic features of biallelic mutations in SORD in a series of chinese patients with charcot-marie-tooth and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:733926.

Antoniadi T, Buxton C, Dennis G, et al. Application of targeted multi-gene panel testing for the diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathy provides a high diagnostic yield with unexpected phenotype-genotype variability. BMC Med Genet. 2015;16:84.

Dong HL, Li JQ, Liu GL, Yu H, Wu ZY. Biallelic SORD pathogenic variants cause Chinese patients with distal hereditary motor neuropathy. NPJ Genom Med. 2021;6:1.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to patients and their family members for their participation and contribution to this work.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number 442/70. Also, the authors would like to extend their appreciation to Taibah University for its supervision support. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. recruited family, performed phenotyping, and wrote the initial draft; S.B. designed the study, analyzed exome data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All study protocols were approved by the scientific research ethics committee of the College of Medicine, Taibah University Medina. The ethical approval ID is 036–1441. Written informed consents were obtained from all the individual members included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alluqmani, M., Basit, S. Association of SORD mutation with autosomal recessive asymmetric distal hereditary motor neuropathy. BMC Med Genomics 15, 88 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01238-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01238-4