Abstract

Background

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline mutations in the folliculin gene (FLCN). Nearly 150 pathogenic mutations have been identified in FLCN. The most frequent pattern is a frameshift mutation within a coding exon. In addition, splice-site mutations have been reported, and previous studies have confirmed exon skipping in several cases. However, it is poorly understood whether there are any splice-site mutations that cause translation of intron regions in FLCN.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old Japanese patient with multiple pulmonary cysts and pneumothorax was hospitalized due to dyspnea. BHD was suspected and genetic testing was performed. The patient exhibited the splice-site mutation of FLCN in the 5′ end of intron 9 (c.1062 + 1G > A). Total mRNA was extracted from pulmonary cysts, and RT-PCR assessment and sequence analyses were done. Two distinct bands were generated; one was wild-type and the other was a larger-sized mutant. Sequence analysis of the latter transcript revealed the insertion of 130 base pairs of intron 9 from the beginning of the splice-site between exons 9 and 10.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of distinct intron insertion using a BHD patient’s diseased tissue-derived mRNA. The present case suggests that a splice-site mutation can lead to exon skipping as well as intron reading mRNA. The splicing process may be dependent in part on whether the donor or acceptor site is affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD), also called Hornstein-Knickenberg syndrome, is an inherited disorder characterized by skin fibrofolliculomas, multiple pulmonary cysts and kidney cancers [1, 2]. The gene responsible for BHD, folliculin (FLCN), is located at 17p11.2. [3], and its protein product, FLCN, cooperatively interacts with its partners folliculin-interacting proteins 1 (FNIP1) and FNIP2, playing important roles in organogenesis and tissue homeostasis [4,5,6,7,8]. The FLCN complex binds with AMPK and regulates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [4,5,6,7,8]. The principal role of FLCN in human diseases is tumor suppression. Around 20–30% of affected family members are reported to develop renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) [2]. Rats carrying a mutant Flcn and heterozygous knockout mice developed renal tumors [9,10,11,12]. Further studies using organ-specific Flcn knockout mice demonstrated characteristic disorders such as polycystic kidney disease, cardiac hypertrophy and alveolar enlargement, indicating that FLCN function is involved in a wide variety of human disorders [13,14,15,16].

There are nearly 150 known mutation patterns of FLCN [17, 18]. The most frequent type is a frameshift within an exon region. Less frequent types include nonsense, in-frame deletion, missense, and splice-site mutations. There are also intragenic deletions and duplications [19, 20]. According to the literature, splice-site mutations have been reported between introns 4–13, and there are at least 19 different splice-site mutation patterns [17, 20]. Some of these splice-site mutations are predicted to cause exon skipping [21, 22]. Several cases possess truncated FLCN mRNAs with exon skipping as determined by RT-PCR [23,24,25]. Recently, a study of splice-site mutation cases involving the 5′-end of intron 9 (c.1062 + 2 T > G) demonstrated 2 mutants; composed of a short band lacking exon 9 and a large band reading an additional 130 base pairs (bp) of intron 9 [26]. The large band was much fainter than the short one, and interpreted as a cryptic splice-site [26]. It is not completely understood whether some splice-site mutations aberrantly translate intron regions, forming unconventional transcriptional products in the affected organs of BHD patients. In the current study, we described a case of BHD in which FLCN mRNAs had splicing aberrations due to translating a part of an intron.

Case presentation

Clinical course

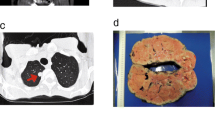

A 59-year-old Japanese man was admitted to Kumamoto Saishunso National Hospital for treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax. Now an ex-smoker, he had previously smoked 10–12 cigarettes per day for 25 years. He had not previously experienced a pneumothorax. He did not have fibrous papules on his face or neck. His medical history was unremarkable except for a benign colon polyp at the age of 58. His two daughters and an uncle on the maternal side had episodes of pneumothoraces (Fig. 1a). His mother had died of cervical cancer, and had had no episode of pneumothorax. Computed tomography showed multiple pulmonary cysts (Fig. 1b). Renal tumors were not detectable. He underwent pulmonary wedge resection via video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Intrathoracic observation revealed transparent cysts 3–30 mm in diameter distributed in the pleura (Fig. 2a, left). After VATS, the patient has recovered without complication, and has been receiving periodic medical check-ups. From the family history and radiological and clinical findings, the patient was suspected of BHD.

Lung histology and FLCN analysis. (a) Left: The thoracoscopy revealed multiple subpleural cysts (arrows). Right: Histology of the resected lung. Pulmonary cysts preferentially develop along an interlobular septum, and they are partially incorporated within alveoli. Neither fibrosis nor active inflammation was observed. Stars indicate cyst lumens. (b) Direct sequencing of the FLCN gene. The 5′-end of intron 9 was heterozygously mutated to adenine (arrow; c.1062 + 1G > A). A homozygous SNP was also detected (arrowhead; c.1062 + 6C > T). (c) RT-PCR of FLCN mRNA between exons 8–11. Two products were detected; a wild type (WT) and a mutant (Mut). (d) Western blotting of FLCN in the patient’s lung. Normal lung was used for comparison. The FLCN bands of 64 kDa were detected in both lanes. No additional band was observed in the BHD patient’s lung. (e) Sequence analysis of mutant RT-PCR product. Intron 9 (130 bp) retention was detected between exons 9–10

Pathological finding

The resected lung tissue contained several cystic lesions. Microscopically, these cysts were incorporated into peripheral alveolar tissue in one region and interstitial tissue or visceral pleura in another area (Fig. 2a, right). Most of the cysts developed in contact with bronchovascular bundles and/or interlobular septa. Flattened pneumocytes lined the inner surface of the cysts, and the lining cells were frequently exfoliated from the wall. The cyst walls showed neither fibrous reaction nor active inflammation, which was distinctively different from the histology of emphysematous bullae. Other cystic lung disorders such as lymphangioleiomyomatosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were also ruled out. The characteristic histological features were consistent with BHD-associated pulmonary cysts [27, 28].

Mutation and expression analysis

Genetic counseling was performed, and informed consent was obtained from the patient for FLCN genetic testing and related molecular studies after approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yokohama City University. Genetic analysis of FLCN identified a single nucleotide mutation at the 5′-end of intron 9 (c.1062 + 1G > A) (Fig. 2b). The mutation had been reported as pathogenic in a previous study [21]. In addition, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was detected in the vicinity of the splice-site mutation (c.1062 + 6C > T). The patient was finally diagnosed with BHD.

Previous studies have identified several sites of exon skipping in FLCN mRNAs in patients with BHD [23,24,25]. The mutation in intron 9 (c.1062 + 1G > A) was predicted to cause aberrant FLCN mRNA, but had not been investigated. We therefore analyzed the patient’s FLCN at mRNA and protein levels. Using primers covering exons 8–11 with RT-PCR, two products were clearly detected, i.e., a wild-type band (413 bp) and a larger-sized band between 500 and 600 bp (Fig. 2c). No candidate band for exon skipping was observed. In Western blotting, predicted size FLCN bands were detected in the BHD lung as well as in a normal lung. No other specific band was detected in the patient’s lung (Fig. 2d). We further performed sequence analysis of the RT-PCR products. A wild-type band was confirmed to be composed of exons 9–10. On the other hand, the larger-sized band of the mutant allele was found between exons 9–10, extending from the beginning of intron 9 for 130 bp (Fig. 2e). The size of the mutant mRNA was determined to be 543 bp. The complete size of intron 9 is 1836 bp; however, no larger band was detectable. Moreover, we did not observe other candidates predicting exon skipping. Reanalysis with RT-PCR using different primers designed between exons 8–13 showed again an identical 130 bp intron inserting between exons 9–10 (data not shown). The amino acid sequence predicted by the mutant mRNA caused a frameshift of exon 10, resulting in premature termination after reading 77 amino acids from the 5′-end of intron 9 (Additional file 1 Figure S1).

Discussion and conclusions

Splice-site mutations are expected to affect mRNA translation by either skipping the adjacent exon or misreading the affected intron. Splice-sites are composed of acceptor sites (the 3′-end of the intron) and donor sites (the 5′-end of the intron). In BHD families, there are more acceptor site than donor site mutations [17]. All of the cases in which exon skipping was confirmed were acceptor site mutations, such as c.397-1G > C, c.1063-2A > G and c.1177-2A > G [23,24,25]. With regard to donor site mutations, only one study has been reported thus far [26]. Rossing et al. used a mini-gene splicing assay to demonstrate the presence of 2 simultaneous bands in the case of c.1062 + 2 T > G; i.e., an additional 130 bp and an exon skipping [26]. The former sequence was interpreted as a misreading of intron 9 using a cryptic splice-site. Although the mutation of the present case was located in the other nucleotide (c.1062 + 1G > A), both mutations identically read the first 130 bp of intron 9 and connected with exon 10. At the break point of intron 9, retention stopped before a guanine-thymine (GT) sequence (data not shown). It is plausible that the GT sequence just after the break point could have been misunderstood as a donor site. We could not detect exon skipping in the present study, which might owe in part to experimental design. We investigated mRNA expression using the patient’s lung that contained cystic lesions, whereas Rossing et al. used mRNA from transfected COS-7 cells.

A partial intron retention (130 bp) and the following 104 bp of exon 10, which ended at a stop codon, predicted the translation of an additional 77 amino acids between intron 9 (43 amino acids) and exon 10 (34 amino acids). In the latter amino acids involving exon 10, a frameshift occurred due to a guanine left behind the 43 amino acids. We could not detect candidate bands for the mutant protein in Western blotting analysis. Similar results were obtained in our previous study of another patient’s lung with a splice-site mutation in the acceptor site [24]. Although the possible presence of FLCN variants that are undetectable by currently available antibodies cannot be excluded, these pathogenic mRNAs might be degraded through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay system. Significant expression of normal-sized FLCN in patients’ lungs indicates that the majority of normal-looking pneumocytes preserve FLCN at the protein level in human BHD lungs. On the other hand, FLCN protein is reduced or severely suppressed in BHD-associated RCCs [29]. Since the mice with Flcn-depleted type II pneumocytes resulted in alveolar enlargement [15], undetectable levels of FLCN suppression in a limited number of pneumocytes might also contribute to cyst growth. The characteristic localization of cysts in the vicinity of interlobular septa/bronchovascular bundles and visceral pleura, as well as development of elongated vascular network in subpleural cysts [28], suggest that the cysts may originate from specific areas that would slowly lead to cystic growth of the alveolar epithelium with partial incorporation into stroma. A recent in vitro study of pulmonary fibroblasts from BHD patients demonstrated impaired migration and matrix production abilities, suggesting the roles of stroma at shear stress-prone regions of the lung [30]. In this respect, we observed a histopathological analogy between BHD-associated pulmonary cysts and fibrofolliculomas of the skin, the latter also showing cord-like growth of follicular epithelium in association with the surrounding specialized mesenchyme.

The results of the present case and previous studies that demonstrate intron retention and exon skipping are summarized in Fig. 3. We hypothesize that mutations in donor/acceptor sites may play critical roles for determining mRNA processing. The possibilities of aberrant splicing should be considered including condition-dependent processing and cryptic splicing. Further study is needed to determine whether splice-site mutations in other donor sites also cause partial/complete intron retention or produce exon-skipped mRNA in a condition-dependent manner. Better understanding of mRNA processing from mutant FLCN will contribute to medical care of BHD patients.

mRNA processing of FLCN with splice-site mutations Green boxes are exons and white boxes are introns. Each intron has guanine and thymidine (GT) at the 5′-end and adenine and guanine (AG) at the 3′-end. A yellow notch indicates a mutated region of intron X. (a) Two patterns of 5′-end mutation, i.e., the present case and ref. [26], demonstrated intron retention. The latter noted the mutant cryptic. (b) Eight patterns of 3′-end mutation (refs. [23,24,25]) demonstrated exon skipping

Abbreviations

- BHD:

-

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

- FLCN :

-

Folliculin

- VATS:

-

Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery

References

Menko FH, van Steensel MA, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen L, Richard S, Ungari S, Nordenskjold M, Hansen TV, Solly J, Maher ER. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1199–206.

Toro JR, Wei MH, Glenn GM, Weinreich M, Toure O, Vocke C, Turner M, Choyke P, Merino MJ, Pinto PA, et al. BHD mutations, clinical and molecular genetic investigations of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: a new series of 50 families and a review of published reports. J Med Genet. 2008;45(6):321–31.

Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, Matrosova V, Glenn G, Turner ML, Duray P, Merino M, Choyke P, Pavlovich CP, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(2):157–64.

Baba M, Hong SB, Sharma N, Warren MB, Nickerson ML, Iwamatsu A, Esposito D, Gillette WK, Hopkins RF 3rd, Hartley JL, et al. Folliculin encoded by the BHD gene interacts with a binding protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is involved in AMPK and mTOR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(42):15552–7.

Hasumi H, Baba M, Hong SB, Hasumi Y, Huang Y, Yao M, Valera VA, Linehan WM, Schmidt LS. Identification and characterization of a novel folliculin-interacting protein FNIP2. Gene. 2008;415(1–2):60–7.

Takagi Y, Kobayashi T, Shiono M, Wang L, Piao X, Sun G, Zhang D, Abe M, Hagiwara Y, Takahashi K, et al. Interaction of folliculin (Birt-Hogg-Dube gene product) with a novel Fnip1-like (FnipL/Fnip2) protein. Oncogene. 2008;27(40):5339–47.

Hasumi H, Baba M, Hasumi Y, Lang M, Huang Y, Oh HF, Matsuo M, Merino MJ, Yao M, Ito Y, et al. Folliculin-interacting proteins Fnip1 and Fnip2 play critical roles in kidney tumor suppression in cooperation with Flcn. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(13):E1624–31.

Baba M, Toyama H, Sun L, Takubo K, Suh HC, Hasumi H, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Hasumi Y, Klarmann KD, Nakagata N, et al. Loss of Folliculin disrupts hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and homeostasis resulting in bone marrow failure. Stem Cells. 2016;34(4):1068–82.

Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(5):277–85.

Kouchi M, Okimoto K, Matsumoto I, Tanaka K, Yasuba M, Hino O. Natural history of the Nihon (Bhd gene mutant) rat, a novel model for human Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Virchows Arch. 2006;448(4):463–71.

Chen J, Futami K, Petillo D, Peng J, Wang P, Knol J, Li Y, Khoo SK, Huang D, Qian CN, et al. Deficiency of FLCN in mouse kidney led to development of polycystic kidneys and renal neoplasia. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3581.

Hartman TR, Nicolas E, Klein-Szanto A, Al-Saleem T, Cash TP, Simon MC, Henske EP. The role of the Birt-Hogg-Dube protein in mTOR activation and renal tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(13):1594–604.

Baba M, Furihata M, Hong SB, Tessarollo L, Haines DC, Southon E, Patel V, Igarashi P, Alvord WG, Leighty R, et al. Kidney-targeted Birt-Hogg-Dube gene inactivation in a mouse model: Erk1/2 and Akt-mTOR activation, cell hyperproliferation, and polycystic kidneys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(2):140–54.

Hasumi H, Baba M, Hasumi Y, Huang Y, Oh H, Hughes RM, Klein ME, Takikita S, Nagashima K, Schmidt LS, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism by tumor suppressor FLCN. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(22):1750–64.

Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, James ML, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Stepanova V, Hong SB, Li H, Gonzales L, Baba M, Linehan WM, et al. Folliculin controls lung alveolar enlargement and epithelial cell survival through E-cadherin, LKB1, and AMPK. Cell Rep. 2014;7(2):412–23.

Hasumi Y, Baba M, Hasumi H, Huang Y, Lang M, Reindorf R, Oh HB, Sciarretta S, Nagashima K, Haines DC, et al. Folliculin (Flcn) inactivation leads to murine cardiac hypertrophy through mTORC1 deregulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(21):5706–19.

Lim DH, Rehal PK, Nahorski MS, Macdonald F, Claessens T, Van Geel M, Gijezen L, Gille JJ, Giraud S, Richard S, et al. A new locus-specific database (LSDB) for mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(1):E1043–51.

Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(10):558–69.

Benhammou JN, Vocke CD, Santani A, Schmidt LS, Baba M, Seyama K, Wu X, Korolevich S, Nathanson KL, Stolle CA, et al. Identification of intragenic deletions and duplication in the FLCN gene in Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(6):466–77.

Zhang X, Ma D, Zou W, Ding Y, Zhu C, Min H, Zhang B, Wang W, Chen B, Ye M, et al. A rapid NGS strategy for comprehensive molecular diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome in patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):64.

Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Glenn GM, Toro JR, Merino MJ, Turner ML, Choyke PL, Sharma N, Peterson J, et al. Germline BHD-mutation spectrum and phenotype analysis of a large cohort of families with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(6):1023–33.

Furuya M, Yao M, Tanaka R, Nagashima Y, Kuroda N, Hasumi H, Baba M, Matsushima J, Nomura F, Nakatani Y. Genetic, epidemiologic and clinicopathologic studies of Japanese Asian patients with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Clin Genet. 2016;90(5):403–12.

Kunogi M, Kurihara M, Ikegami TS, Kobayashi T, Shindo N, Kumasaka T, Gunji Y, Kikkawa M, Iwakami S, Hino O, et al. Clinical and genetic spectrum of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome patients in whom pneumothorax and/or multiple lung cysts are the presenting feature. J Med Genet. 2010;47(4):281–7.

Nishii T, Tanabe M, Tanaka R, Matsuzawa T, Okudela K, Nozawa A, Nakatani Y, Furuya M. Unique mutation, accelerated mTOR signaling and angiogenesis in the pulmonary cysts of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Pathol Int. 2013;63(1):45–55.

van Steensel MA, Verstraeten VL, Frank J, Kelleners-Smeets NW, Poblete-Gutierrez P, Marcus-Soekarman D, Bladergroen RS, Steijlen PM, van Geel M. Novel mutations in the BHD gene and absence of loss of heterozygosity in fibrofolliculomas of Birt-Hogg-Dube patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(3):588–93.

Rossing M, Albrechtsen A, Skytte AB, Jensen UB, Ousager LB, Gerdes AM, Nielsen FC, Hansen TV. Genetic screening of the FLCN gene identify six novel variants and a Danish founder mutation. J Hum Genet. 2017;62(2):151–7.

Koga S, Furuya M, Takahashi Y, Tanaka R, Yamaguchi A, Yasufuku K, Hiroshima K, Kurihara M, Yoshino I, Aoki I, et al. Lung cysts in Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: histopathological characteristics and aberrant sequence repeats. Pathol Int. 2009;59(10):720–8.

Furuya M, Nakatani Y. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: clinicopathological features of the lung. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(3):178–86.

Furuya M, Hong SB, Tanaka R, Kuroda N, Nagashima Y, Nagahama K, Suyama T, Yao M, Nakatani Y. Distinctive expression patterns of glycoprotein non-metastatic B and folliculin in renal tumors in patients with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(3):315–23.

Hoshika Y, Takahashi F, Togo S, Hashimoto M, Nara T, Kobayashi T, Nurwidya F, Kataoka H, Kurihara M, Kobayashi E, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the folliculin gene leads to impaired functions of lung fibroblasts in patients with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(21):e13025.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Takashi Ohba for the help of genetic counseling, and Ms. Hiromi Soeda and members of the pathology laboratories in Saishunso National Hospital for excellent assistance.

Availability of data and materials

All data, without identifiers, will be available per reasonable request. The contact person is M. Furuya, email: mfuruya@yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF, KH, MB, TI and RT analyzed and interpreted the data. KH and MB contributed to clinical management. MF, MB, and YN contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies of germline and somatic mutations of FLCN and related molecular analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Yokohama City University (A161100001), and written informed consent for the studies was obtained from the patient. We confirmed that all processes were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines including the CARE case report guidelines.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 26460422 (M.F.) 15 K08374 (Y.N.), 15,604,475 (M.B.), 15,551,829 (M.B.) and Project Mirai Cancer Research Grants (M.F.) in the writing of the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Amino acid sequence predicted by intron retention. Colored nucleotides are exons 9 and 10, and gray nucleotides starting from the mutated adenine (A, indicated by an arrow) are intron insertions. The predicted amino acid sequence is noted below codons in bold. A 130 bp intron retention leads to a frameshift from the beginning of exon 10, which results in premature termination (indicated by a rectangle). (PPTX 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Furuya, M., Kobayashi, H., Baba, M. et al. Splice-site mutation causing partial retention of intron in the FLCN gene in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a case report. BMC Med Genomics 11, 42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-018-0359-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-018-0359-5