Abstract

Background

The present study aimed to direct detect Mycobacterium bovis in milk (n = 401) and blood (n = 401) samples collected from 401 dairy cows of 20 properties located in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) targeting the region of difference 4 (RD4). Risk factors possibly associated with bovine tuberculosis (BTB) were also evaluated.

Results

Of the 802 samples analyzed, one milk (0.25 %) and eight blood (2 %) samples were positive for M. bovis in the qPCR and their identities were confirmed by sequencing. Animals positive for M. bovis were found in six (30 %) of the 20 properties visited. None of the risk factors evaluated were statistically associated with BTB.

Conclusions

M. bovis DNA was detected in one milk sample what may pose a risk to public health because raw milk is commonly consumed in Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is caused by Mycobacterium bovis, a member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex that affects mammals, including humans [1].

M. bovis has been isolated from milk and colostrum samples what can be important to perpetuate BTB infection in a herd through the digestive route [2]. Raw milk is commonly consumed in Brazil [3] and clandestine milk is an important public health issue in the country [4, 5].

Despite the fact that Brazil has a National Program for Control and Eradication of Tuberculosis and Brucellosis (Programa Nacional de Controle e Erradicação da Tuberculose e da Brucelose - PNCETB) supervised by a public agency, its implementation is not mandatory [6]. The tuberculin skin test is the diagnostic method recommended by the PNCETB and it must be followed by bacterial isolation for result confirmation [7]. Efforts to reduce the risk of M. bovis infection must include sanitary measures to ensure a healthy cattle herd.

Molecular techniques such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) have been used for BTB diagnosis in several clinical samples such as blood, milk and nasal exudates [2]. Standardization of direct methods for detection of M. bovis in clinical samples will enable a more accurate BTB diagnosis and facilitate epidemiological studies on M. bovis prevalence [1, 8].

In the present study, we used qPCR for direct detection of Mycobacterium bovis in milk and blood samples of cattle from the state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

Methods

Sampling

The sample size was calculated as recommended by Thrusfield [9] using the following parameters: bovine population of 336,221 animals in the micro region of Garanhuns, state of Pernambuco, Brazil [10], 95 % confidence interval and 5 % sampling error margin using a prevalence of 50 %, since there is no official data on BTB prevalence in the studied region. According to the calculation, the minimum sample size should be 385 dairy cattle.

From January to February 2014, a total of 802 milk and blood samples were collected from 401 dairy cows of 20 properties distributed in the municipalities of Angelim, Bom Conselho, Brejão, Caetés, Calçado, Canhotinho, Correntes, Garanhuns, Iati, Jucati, Jupi, Jurema, Lagoa do Ouro, Lajedo, Palmeirina, Paranatama, Saloá, São João and Terezinha, state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

Written informed consent was obtained from the farmers to take samples from the cattle. The blood samples (n = 401) were collected by caudal venipuncture, stored in tubes containing citrate, properly identified and sent to the Garanhuns Laboratories Center (Central de Laboratórios de Garanhuns - CENLAG), located in the Garanhuns Academic Unit (Unidade Acadêmica de Garanhuns - UAG) of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco - UFRPE), Brazil.

The milk samples (n = 401), which consisted of 50 ml of a pool of milk from the four quarters of each cow, were collected during milking after the udder disinfection with 70 % alcohol and the first jets of milk were discarded. Then the samples were stored in sterile bottles, cooled and sent to the CENLAG (UAG- UFRPE).

An epidemiological questionnaire containing multiple-choice questions concerning animal production characteristics, hygiene and sanitary aspects of the herd, and reproductive management was applied in each property. The questionnaire comprised 11 possible risk factors for M. bovis infection, as follows: herd size (less than 50 animals, 51–100 animals, 101–200 animals, more than 201 animals), rearing system (intensive, extensive, semi-intensive), origin of replacement animals (farm’s own herd, another farm, both), conducting quarantine after animal’s purchase, performance of BTB diagnostic tests upon animals’ acquisition, water source (stagnant or running), milking procedure (manual or mechanic), frequency of cleaning the farm facilities, udder disinfection, feeding colostrum to calves and history of BTB in the herd.

DNA Extraction

M. bovis DNA was extracted from milk samples using the QIamp® kit (Qiagen Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Leukocyte DNA was isolated by a modified phenol-chloroform extraction method [11], 100 μl of white blood cells were used, ammonium acetate and phenol-chloroform for DNA extraction from the blood samples.

Positive control

The Mycobacterium bovis ATCC 19274 strain was gently provided by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fundação Osvaldo Cruz - FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and was used for construction of a plasmid harboring the target sequence, which was the positive control in the molecular assays. M. bovis genomic DNA was extracted and the fragment corresponding to the region of difference 4 (RD4) was amplified with the specific primers reported by Sales et al. [12]. The target fragment was cloned using Escherichia coli XL1 blue strain and TA cloning kit® (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The recombinant plasmid pRD4-TA was sequenced by the Sanger method using an ABI3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

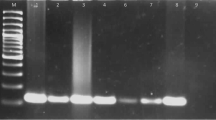

Real-time PCR

The molecular detection of M. bovis DNA in the milk and blood samples was performed in the Laboratory of Immunogenetics (Laboratório de Imunogenética) of FIOCRUZ, state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the same primer set used for amplification of the RD4 fragment of the positive control and a fluorescent probe that discriminates M. bovis from other M. tuberculosis complex members since it hybridizes with both the 5′ and 3′ RD4 deletion flanking sequences, which only occur directly adjacent to each other in M. bovis. The probe was designed using the software Primer Express® Software and targeted a region in the amplicon in between the primer pair. The probe showed 100 % homology to M. bovis in BLAST/ncbi. Probe sequence: 5’- /56-FAM/AGCCGTAGTCGTGCAGAAGCGCA/3BHQ_1/- 3’. The total reaction volume was 25 μL comprising 2.0 μL of DNA, 12.5 μL of TaqMan®Universal PCR Master Mix, 1.0 μL each primer (5 pmol), 0.5 μL of probe (5 pmol) and water (8 μL). The amplification conditions were 95 °C for 15 min (denaturation) followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. In all PCR runs, standard curves were obtained using the positive control, plasmid DNA encompassing the mycobacteria RD4 sequence, which was prepared in triplicate by serial dilution of 10x plasmid DNA from 200 ng (Quantification cycle - Cq = 11.8) to 0.0002 ng (Cq = 32.2). The qPCR was performed in an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system set for absolute quantification The slope of the standard curve was −3.40 and R = 0.999, with 97 % efficiency.

Spiked samples were not used. The standard curve and the detection limit were determined using a serial 10X dilution from 100 to 10−10 ng/ul in triplicate and the positive control was detected in samples with up to 10−6 ng/ul. The reaction was repeated four times in different days and the same results were obtained in each day.

To verify the presence of inhibitors in the samples, a few blood samples of 1000 ng/μl DNA were randomly selected and diluted them to 800, 600, 400, 200 and 50 ng/μl of DNA. Then 20 ng were added of positive control to the diluted samples and performed a qPCR. All the dilutions had the same Cq in the qPCR; therefore, there were no inhibitors in the samples.

Sequencing

DNA sequencing was performed in the Center of Technological Platforms (Núcleo de Plataformas Tecnológicas - NPT), of the Research Center Aggeu Magalhães (Centro de Pesquisas Aggeu Magalhães-CPqAM), FIOCRUZ, state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

The commercial kit ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction v3.1 (Applied Biosystems®) was used for DNA sequencing following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The RD4 fragments were sequenced by the Sanger method and the reaction products were analyzed in the ABI 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

All the sequences obtained in the present study were compared with the RD4 fragment of the reference genome (88 bp) (GenBank Access number BX248339.1) using the software Blast-N (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and MEGA6 [13].

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee on Animal Use (Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais – CEUA) of UFRPE provided scientific and ethical clearance for the present study (reference number 23082.004671/2013, license number 028/2013).

Statistical analysis

The absolute and relative prevalence of M. bovis in the milk and blood samples were determined by descriptive analysis. Univariate analysis using chi-square test, Pearson’s test or Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the possible risk factors associated with BTB. All statistical analyzes were performed in the Epi Info 3.5.1 software.

Results

Of the 802 samples analyzed, one milk (0.25 %) and eight blood (2 %) samples were positive for M. bovis in the qPCR and their identities were confirmed by sequencing. All positive samples were from different animals (Table 1).

Six (30 %) of the 20 properties visited had animals positive for M. bovis (Table 1). None of the risk factors evaluated in the present study were statistically associated with BTB as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

This is the first report of direct detection of M. bovis DNA in milk and blood samples from cattle of the region of Garanhuns, state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

The prevalence of M. bovis DNA in milk samples ranges from 2 to 87 % according to different studies [14–20], which evaluated the mycobacteria presence by PCR. The different prevalence rates observed by them may be related to management characteristics [21], sampling methods [22] and disease-control measures adopted in each location [23].

The presence of M. bovis in milk may pose a risk to public health, because humans can become infected by M. bovis through exposure to infected animals, consumption of infected raw milk and dairy products [24, 25]. The presence of M. bovis in milk samples is a concern because it is estimated that 41 % of all milk consumed in Brazil is not pasteurized [12] being a source of infection of human TB. Since the clinical symptoms of human TB caused by M. bovis are indistinguishable from those caused by M. tuberculosis [23, 26], a detailed epidemiological investigation considering the patients eating habits and professional occupation must be performed by the health surveillance service to determine the TB causal agent. In Brazil, a study performed by Silva et al. [27] with 189 TB patients identified co-infection with M. bovis in three patients. In two of these patients, consumption of cheese made with raw milk was the probable cause of infection. The other patient used to work in a slaughterhouse, so the infection was related to labor risk. Other study conducted in Brazil also identified M. bovis in humans, although with lower prevalence. It is believed that M. bovis prevalence in Brazil is underestimated [28].

In the present study, the milk sample positive for M. bovis did not belong to any of the eight animals that had positive blood samples what can be explained by various reasons: collection of only one milk sample per dairy cow, interaction between the bacillus and the bovine immune system cells, which may have decreased the amount of bacillus in milk [2, 20, 29], and presence of milk proteins and fat that may have impaired the extraction of M. bovis DNA from the milk samples [14, 30]. Despite these limitations, studies using experimentally contaminated milk have demonstrated that PCR can detect the mycobacteria in milk samples with much lower concentrations of M. bovis DNA than the concentration usually present in natural infections [2, 20, 29, 31]. The mycobacteria has been more frequently identified in blood than in milk samples [20, 32, 33].

Another factor that can hinder the detection of M. bovis in milk is its intermittent release during a short period post-infection [20, 29]. Pardo et al. [34] evaluated the mycobacteria secretion pattern in 780 milk samples collected from 52 animals for 15 consecutive days and M. bovis showed an intermittent and irregular release pattern in 26.5 % of the samples [34].

In the present study, of the six farms that had animals positive for M. bovis, only one have a history of performing tuberculin tests upon acquisition of new animals. According to the farmer, all the animals were negative for M. bovis in the tuberculin tests. This data shows the importance of using tests that are more sensitive in enzootic areas, as the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, where cases of BTB have already been identified using tuberculin skin test [35, 36].

Although there was no statistical association between herd size and M. bovis positivity, the mycobacteria was more prevalent in larger herds (101–200 animals). Herd size can influence BTB epidemiology because a high population density favors a more frequent contact between animals, facilitating the mycobacteria dissemination [37, 38].

According to Skuce et al. [39], M. bovis can survive in water what favors its dissemination. M. bovis DNA was identified in water samples experimentally contaminated even 11 months after contamination [40]. In Uganda, Africa, where cattle commonly drinks running water from rivers or streams, a study evaluated the risk factors associated with BTB and concluded that the water source was statistically associated with the disease [41]. However, in the present study, no correlation was found between water source and presence of M. bovis in milk and blood samples (Table 1). The fact that water sources could be implicated with BTB transmission may be a concern to health authorities, because control measures would also have to consider this contamination source besides slaughter of positive animals.

Despite the higher number of animals positive for M. bovis in herds with low frequency of cleaning the farm facilities and lack of udder disinfection before milking, no positive correlation was found between pathogen presence and these risk factors. Roxo [42] reported that cleaning, disinfection and hygiene are risk factors for TB. Waste management and treatment of organic matter can influence M. bovis prevalence in areas with previous cases of TB [43].

Conclusion

M. bovis DNA was detected in one milk sample what may pose a risk to public health. We suggest that environmental control measures should be implemented in farms at high risk of TB transmission because environmental factors contribute to bacteria perpetuation and dissemination.

References

Taylor GM, Worth DR, Palmer S, Jahans K, Hewinson RG. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in cattle lymph nodes with visible lesions using PCR. BMC Vet Res. 2007;3:12. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-3-12.

Serrano-Moreno BA, Romero TA, Arriaga C, Torres RA, Pereira-Suárez AL, García-Salazar JA, et al. High frequency of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in colostra from tuberculous cattle detected by nested PCR. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:258–66. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01125.x.

Milka CDA, Grace BDS, Fernando Z, Maurcio CH, Francesca SD, Mateus MDC. Microbiological evaluation of raw milk and coalho cheese commercialised in the semi-arid region of Pernambuco, Brazil. African J Microbiol Res. 2014;8:222–9. doi:10.5897/AJMR2013.6476.

Bermudez HR, Henteira ET, Medina BG, Hori-Oshima S, De La Mora VA, Lopez VG, et al. Correlation between histopathological, Bacteriological and PCR diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. J Anim Vet Adv. 2010;9:2082–4.

Sgarioni SA, Dominguez R, Hirata C, Hirata MH, Queico C, Leite F, et al. Occurrence of Mycobacterium bovis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in raw and pasteurized milk in the northwestern region of Paraná, Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;711:707–11.

BRASIL. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Programa Nacional de Controle e Erradicação da Brucelose e da Tuberculose Animal (PNCEBT). Brasília, 2006. http://www.agricultura.gov.br/arq_editor/file/Aniamal/programa%20nacional%20sanidade%20brucelose/Manual%20do%20PNCEBT%20-%20Original.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Araujo CP, Osório ALAR, Jorge KSG, Ramos CAN, Filho AFS, Vidal CES, Vargas APC, et al. Direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in bovine and bubaline tissues through nested-PCR. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;45:633–40.

Majeed MA-M, Ahmed WA, Manki A. Amplification of a 500 base-pair fragment from routinely identified isolates of m . Bovis from cow’s milk in Baghdad. IJABR. 2013;3:163–7.

Thrusfield MV. Epidemiologia Veterinária. 2ª ed. São Paulo: ROCA; 2004.

IBGE – Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2005. Available from: http://www.sidra.ibge.gov.br/bda/territorio/unit.asp?e=c&t=71&p=CA&v=2057&codunit=6186&z=t&o=4&i=P. A. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. p. 3.

Sales ML, Jr AAF, Orzil L, Alencar AP, Hodon MA. Validation of two real-time PCRs targeting the PE-PGRS 20 gene and the region of difference 4 for the characterization of Mycobacterium bovis isolates. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:4607–16.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

Zumárraga MJ, Soutullo A, García MI, Marini R, Abdala A, Tarabla H, et al. Infected dairy herds using PCR in bulk tank milk samples. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:132–7. doi:10.1089/fpd.2011.0963.

Franco MMJ, Paes AC, Ribeiro MG, de Figueiredo Pantoja JC, Santos ACB, Miyata M, et al. Occurrence of mycobacteria in bovine milk samples from both individual and collective bulk tanks at farms and informal markets in the southeast region of Sao Paulo, Brazil. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:2–8. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-9-85.

Zarden CFO, Marassi CD, Figueiredo EEES, Lilenbaum W. Mycobacterium bovis detection from milk of negative skin test cows. Vet Rec. 2013;172:130. doi:10.1136/vr.101054.

El-Gedaway AA, Ahmed HA, Awadallah MAI. Occurrence and molecular characterization of some zoonotic bacteria in bovine milk, milking equipment and humans in dairy farms, Sharkia, Egypt. Int Food Res J. 2014;21:1813–23.

Mohamed SA, Aggour MG, Ahmed HA, Selim SA. Detection and differentiation between mycobacterium bovis and mycobacterium tuberculosis in cattle milk and lymph nodes using multiplex real-time PCR. Global Veterinaria. 2014;13:794–800. doi:10.5829/idosi.gv.2014.13.05.86179.

Senthil NR, Ranjani MR, Vasumathi K. Comparative diagnosis of Mycobacterium bovis by Polymerase chain reaction and Ziel- Neilson staining technique using Milk and nasal washing. J Res Agri Animal Sci. 2014;2:1–3.

Carvalho RCT, Castro VS, Fernandes DVGS, Moura GF, Santos ECC, Paschoalin VMF, et al. Use of the Pcr for detection mycobacterium bovis in milk. Proc XII Lat Am Congr Food Microbiol Hyg. 2014;1:359–60. doi:10.5151/foodsci-microal-180.

Evangelista TBR, De Anda JH. Tuberculosis in dairy calves: risk of Mycobacterium spp. exposure associated with management of colostrum and milk. Prev Vet Med. 1996;27:23–7. doi:10.1016/0167-5877(95)00573-0.

Katale BZ, Mbugi EV, Karimuribo ED, Keyyu JD, Kendall S, Kibiki GS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for infection of bovine tuberculosis in indigenous cattle in the Serengeti ecosystem, Tanzania. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:267. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-9-267.

Silaigwana B, Green E, Ndip RN. Molecular detection and drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from cattle at a dairy farm in the Nkonkobe region of South Africa: A pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2045–56. doi:10.3390/ijerph9062045.

Rowe MT, Donaghy J. Mycobacterium bovis: The importance of milk and dairy products as a cause of human tuberculosis in the UK. A review of taxonomy and culture methods, with particular reference to artisanal cheeses. Int J Dairy Technol. 2008;61:317–26. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0307.2008.00433.x.

Ereqat S, Nasereddin A, Levine H, Azmi K, Al-Jawabreh A, Greenblatt CL, et al. First-time detection of Mycobacterium bovis in livestock tissues and milk in the West Bank. Palestinian Territories PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2417. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002417.

Malama S, Muma JB, Olea-Popelka F, Mbulo G. Isolation of mycobacterium bovis from human sputum in Zambia: public health and diagnostic significance. J Infect Dis Ther. 2013;1:2. doi:10.4172/jidt.1000114.

Silva MR, Rocha AS, da Costa RR, de Alencar AP, de Oliveira VM, Fonseca Junior AA, et al. Tuberculosis patients co-infected with Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an urban area of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:321–7.

Kantor IN, Ambroggib M, Poggib S, Morcillo N, Telles MAS, Marta Ribeiro MO, Torres MDG, et al. Human Mycobacterium bovis infection in ten Latin American countries. Tuberculosis. 2008;88:358–65.

Figueiredo EES, Junior CQC, Adam C, Furlaneto LV, Silvestre FG, Duarte RS. et al. Molecular techniques for identification of species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: the use of multiplex PCR and an adapted HPLC method for identification of Mycobacterium bovis and diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. Underst Tuberc - Glob Exp Innov Approaches to Diagnosis 2012:411–432. Available in available in http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs-wm/28550.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Kich DM, Kreling CS, Pozzobon A. Análise da presença de mycobacterium bovis através da técnica de reação em cadeia da polimerase (pcr) em amostras de leite bovino in natura na região do Vale do Raquari, RS. Revista Destaques Acadêmicos. 2012;4:19–26.

Jordão-Junior CM, Lopes FCM, Pinto MRA, Roxo E, Leite CQF. Delevopment of a PCR assay for the direct detection of Mycobacterium bovis in milk. Brazilian J Food Nutr. 2005;16:51–5.

Romero RE, Garzón DL, Mejía GA, Monroy W, Patarroyo ME, Murillo LA. Identification of Mycobacterium bovis in bovine clinical samples by PCR species-specific primers. Can J Vet Res. 1999;63:101–6.

Srivastava K, Chauhan DS, Gupta P, Singh HB, Sharma VD, Yadav VS, et al. Isolation of Mycobacterium bovis & M. tuberculosis from cattle of some farms in north India--possible relevance in human health. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:26–31.

Pardo RB, Langoni H, Mendonça LJP, Chi KD. Isolation of Mycobacterium spp. in milk from cows suspected or positive to tuberculosis. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci. 2001;38:284–7.

Izael MA, Silva STG, Costa NA. Estudo retrospectivo da ocorrência dos casos de tuberculose bovina diagnosticados na clínica de bovinos de Garanhuns - PE, de 2000 A 2009. Brazilian Animal Sci. 2009;1:452–7.

Mendes EI, Melo LEH, Tenório TGS, Sá LM, Souto RJC, Fernandes ACC, et al. Intercorrência entre leucose enzoótica e tuberculose em bovinos leiteiros do estado de Pernambuco. Arq Inst Biol. 2011;78:1–8.

Humblet MF, Gilbert M, Govaerts M, Fauville-Dufaux M, Walravens K, Saegerman C. New assessment of bovine tuberculosis risk factors in Belgium based on nationwide molecular epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2802–8. doi:10.1128/JCM.00293-10.

Humblet MF, Boschiroli ML, Saegerman C. Classification of worldwide bovine tuberculosis risk factors in cattle: A stratified approach. Vet Res 2009;40. doi:10.1051/vetres/2009033.

Skuce RA, Allen AR, McDowell SWJ. 2011. Bovine tuberculosis (TB): a review of cattle-to-cattle transmission, risk factors and susceptibility. https://www.dardni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/dard/afbi-literature-review-tb-review-cattle-to-cattle-transmission.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Adams AP, Bolin SR, Fine AE, Bolin CA, Kaneene JB. Comparison of PCR versus culture for detection of Mycobacterium bovis after experimental inoculation of various matrices held under environmental conditions for extended periods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6501–6. doi:10.1128/AEM.02032-13.

Kazoora HB, Majalija S, Kiwanuka N, Kaneene JB. Prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis skin positivity and associated risk factors in cattle from Western Uganda. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;46:1383–90. doi:10.1007/s11250-014-0650-1.

Roxo E. Bovine tuberculosis: review. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico. 1996;63(2):91–7.

Lilenbaum W, Souza GN, Fonseca LDS. Fatores de manejo associados à ocorrência de tuberculose bovina em rebanhos leiteiros do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. R Bras Ci Vet. 2007;14:98–100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RDSC performed the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. NLS, VLAS and JWPJ JG conceived and designed the study, critically revised the paper and acted as the first author’s study supervisors. AFBBF, JMB, PRF, RCL. MAL performed some of the data analysis and critically revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cezar, R.D., Lucena-Silva, N., Filho, A.F.B.B. et al. Molecular detection of Mycobacterium bovis in cattle herds of the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. BMC Vet Res 12, 31 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-016-0656-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-016-0656-1