Abstract

Background

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has been suggested to exert deleterious effects on myocardium and cardiovascular disease (CVD) consequence. We evaluated the associations of EAT thickness with adverse outcomes and its potential mediators in the community.

Methods

Participants without heart failure (HF) who had undergone cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) to measure EAT thickness over the right ventricular free wall from the Framingham Heart Study were included. The correlation of EAT thickness with 85 circulating biomarkers and cardiometric parameters was assessed in linear regression models. The occurrence of HF, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease (CHD), and other adverse events was tracked since CMR was implemented. Their associations with EAT thickness and the mediators were evaluated using Cox regression and causal mediation analysis.

Results

Of 1554 participants, 53.0% were females. Mean age, body mass index, and EAT thickness were 63.3 years, 28.1 kg/m2, and 9.8 mm, respectively. After fully adjusting, EAT thickness positively correlated with CRP, LEP, GDF15, MMP8, MMP9, ORM1, ANGPTL3, and SERPINE1 and negatively correlated with N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), IGFBP1, IGFBP2, AGER, CNTN1, and MCAM. Increasing EAT thickness was associated with smaller left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, thicker left ventricular wall thickness, and worse global longitudinal strain (GLS). During a median follow-up of 12.7 years, 101 incident HF occurred. Per 1-standard deviation increment of EAT thickness was associated with a higher risk of HF (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.19–1.72, P < 0.001) and the composite outcome consisting of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, HF, and death from CVD (adjusted HR [95% CI], 1.23 [1.07–1.40], P = 0.003). Mediation effect in the association between thicker EAT and higher risk of HF was observed with NT-proBNP (HR [95% CI], 0.95 [0.92–0.98], P = 0.011) and GLS (HR [95% CI], 1.04 [1.01–1.07], P = 0.032).

Conclusions

EAT thickness was correlated with inflammation and fibrosis-related circulating biomarkers, cardiac concentric change, myocardial strain impairment, incident HF risk, and overall CVD risk. NT-proBNP and GLS might partially mediate the effect of thickened EAT on the risk of HF. EAT could refine the assessment of CVD risk and become a new therapeutic target of cardiometabolic diseases.

Trial registration

URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00005121.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

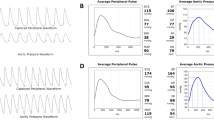

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has gained much attention in recent years as its special anatomical location between the myocardium and visceral pericardium (Fig. 1A), and its functional orientation on the cardiovascular microenvironment, which is characterized by the paracrine or vasocrine secretion of pro-inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines [1, 2]. Increased EAT has been suggested to play a role in the development of coronary heart disease (CHD), atrial fibrillation (AF), and heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [3]. Recent studies have linked coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia to EAT in patients with diabetes mellitus and in post-menopausal women [4, 5]. EAT also contributes to adverse myocardial remodeling after myocardial infarction [6]. In patients with CHD, EAT exhibits predicting ability for adverse cardiovascular events, especially for HFpEF [7, 8]. HFpEF patients have greater EAT thickness than HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [9, 10]. And in HFpEF, the accumulation of EAT was reported to correlate with worse cardiac function, worse exercise capacity, and higher mortality [9,10,11,12]. Such effects of EAT are carried out by mechanical restraint, increased inflammation, autonomic dysregulation, impaired energy utilization, and so on [3, 13]. Current studies remain unclear as to the cardiovascular consequence and underlying mechanism of EAT thickening in the general population. The biochemical and myocardial relevancy of EAT and their contribution to the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes need to be explored. We aim to investigate the circulating biomarkers and cardiometric parameters that correlate with EAT thickness, evaluate the associations of EAT thickness with the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and assess whether these markers mediate the development of adverse outcomes in a community population.

Localization and measurement of epicardial adipose tissue. A Epicardial adipose tissue lies between the myocardium and visceral pericardium. B Epicardial adipose tissue thickness was measured perpendicularly on the free wall of the right ventricle at the mid-ventricular level. EAT, epicardial adipose tissue; RV, right ventricle; RA, right atrium; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium

Methods

Study design and participants

This study included community participants sampled from Framingham, MA, in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) to conduct a longitudinal analysis. Data access was acquired from the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the USA. FHS is a long-term, multigenerational study designed to investigate constitutional and environmental factors influencing the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in men and women [14]. The cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) which assessed EAT thickness was performed on participants in the offspring cohort during their examinations 7 and 8 in 2002 ~ 2006. The offspring cohort consisted of offspring of the original Framingham cohort and spouses of the offspring. The participants with CMR data and free of HF were included in this study. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

EAT thickness and covariates

The EAT thickness was acquired from non-contrast CMR scanning on a 1.5-T Philips scanner (Gyroscan ACS-NT, Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with a 5-element cardiac array coil. After a scout scan, end-expiratory breath-hold, ECG-gated cine steady-state free precession images were acquired in 2-chamber, 4-chamber, and contiguous short axis orientations. Imaging parameters included TR = 3.2 ms, TE = 1.6 ms, flip angle = 60°, field-of-view 400 mm, and matrix size 208 × 256. Slice thickness was 10 mm, and in-plane spatial resolution was 1.9 mm × 1.6 mm, with 30 to 40 ms temporal resolution. Image analysis was performed using the software of MEDIS Inc., LEIDEN (version 6.1 QT). In the horizontal long-axis end-diastolic view (4-chamber), EAT thickness was measured perpendicularly on the free wall of the right ventricle at the mid-ventricular level, which crossed the midpoint between tricuspid annulus and apex cordis (Fig. 1B) [15,16,17].

The age at CMR implementation was recorded and marked the assumed beginning of follow-up. Other baseline information, including body mass index, blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), plasma lipids, and so on, were extracted from the data of examination 8. The determination of the history of diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, or CHD was by the physician-administered medical history review. Dyslipidemia was defined as triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥ 135 mg/dL or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women.

Circulating biomarkers and cardiac measures

During the same study period with CMR, plasma samples of the participants were acquired, and echocardiography was conducted. Plasma samples were utilized to perform immunoassays of 85 circulating protein biomarkers of atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome. The technology being implemented was the Luminex™ xMAP assay, an extension of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay performed with multiple analyte-specific capture antibodies bound to a set of fluorescent beads. An xMAP assay could simultaneously quantify up to 100 analytes at abundances as low as picograms per milliliter in multiple samples. For measurement of cardiac structure and function, most parameters including left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), left atrial internal dimension (LAID), left ventricular wall thickness (LVWT), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were directly obtained from CMR, and global longitudinal strain (GLS) and mitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity (E/é) were assessed by echocardiography in examination 8 [18]. GLS was derived from speckle tracking stain-based analyses performed on digitally recorded 2-dimensional images.

Outcomes

The follow-up examinations were conducted every 4 to 6 years to track the occurrence of incident HF, AF, CHD, and other adverse events through December 2017. Participants were diagnosed as having CHD if there existed one of the following definite manifestations: myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina pectoris, or sudden or non-sudden death from CHD. The composite outcome major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was defined as the presence of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, HF, or death from CVD. The detailed diagnostic criteria of each event are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The participants’ medical records were evaluated using a 3-physician panel by the Framingham Endpoint Review Committee for adjudicating the outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and compared by χ 2 tests and unpaired Student’s t-tests, respectively. The participants were stratified according to the median of EAT thickness, which was consistent with the cut-off value of previous research [19]. The associations of EAT thickness with circulating biomarkers and cardiac measures were assessed using linear regression models, while the associations with clinical outcomes including HF, AF, CHD, and MACE were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models. Cumulative incidence curves of HF stratified by EAT thickness were plotted. When assessing the associations of EAT thickness with the risk of AF or CHD, the participants who presented with AF or CHD at baseline had been excluded. The levels of circulating biomarkers had been processed by logarithmic transformation (natural logarithms) prior to further analysis. The covariates adjusted in each model were sex, age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, eGFR, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, and dyslipidemia. Then, we further conducted a causal mediation analysis to see if any of the circulating biomarkers or cardiac measures alters the association between EAT thickness and clinical outcomes. First, we screened out the circulating biomarkers or cardiac measures which simultaneously correlated with both the EAT thickness and the clinical outcomes. Next, the shortlisted indicators were put into causal mediation analysis provided by Huang YT and Yang HI [20], as instrumental variables, with EAT thickness as the independent variable and clinical outcomes as the dependent variable. The statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-tailed P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The population characteristics at CMR implementation are shown in Table 1. The total 1554 participants had a mean age of 63.3 years (ranging from 35 to 88 years), and 53.0% females, with a mean body mass index of 28.1 kg/m2. The mean EAT thickness was 9.8 mm. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus, AF, CHD, and dyslipidemia were 12%, 4.1%, 7.5%, and 69.2%, respectively. The averages of LVEF, GLS, and E/é were 67.3%, − 20.6%, and 7.0, respectively. Compared to the participants with EAT < 9 mm, those with EAT ≥ 9 mm were predominantly males and older and had larger body mass index, greater systolic blood pressure, faster heart rate, higher triglyceride, lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and higher fasting blood glucose. Participants with EAT ≥ 9 mm had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, CHD, and dyslipidemia and had larger left atrial and left ventricular chambers, thicker LVWT, worse GLS, and worse E/é, compared to those with EAT < 9 mm. There was no difference in LVEF regarding different EAT. Besides, 788 participants had evaluated baseline right ventricular structure. Compared to the participants with EAT < 9 mm, those with EAT ≥ 9 mm had larger right ventricular diameter and area (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Associations of circulating biomarkers and cardiac measures with EAT thickness

As presented in Table 2, after adjusting for common risk factors, EAT thickness was significantly correlated with 14 biomarkers. A positive correlation was found with CRP, LEP, GDF15, MMP8, MMP9, ORM1, ANGPTL3, and SERPINE1 and a negative correlation was with N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), IGFBP1, IGFBP2, AGER, CNTN1, and MCAM. The expressions of these 14 biomarkers have significant differences between participants with EAT < 9 mm and ≥ 9 mm (Additional file 1: Table S3). The associations of all 85 biomarkers with EAT thickness are shown in Additional file 1: Table S4. For cardiac structure and function, per 1-SD increment of EAT thickness was associated with smaller LVEDD (β − 0.23, standard error [SE] 0.11, P = 0.040), thicker LVWT (septal, β [SE], 0.07 [0.03], P = 0.029; inferior, β [SE], 0.09 [0.03], P = 0.002), and worse GLS (β [SE], 0.34 [0.09], P < 0.001).

Association between EAT thickness and adverse cardiovascular outcomes

The associations between EAT thickness and adverse outcomes including incident HF, AF, CHD, and the composite outcome MACE are reported in Table 3. There were 101 incident HF events that occurred during the follow-up of the median 12.7 years, and the incident rate was 0.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.4–0.7) per 100 person-year. The population characteristics according to the occurrence of incident HF are shown in Additional file 1: Table S5. The baseline EAT thickness of the participants who suffered from incident HF in the follow-up has no difference between those with reduced LVEF and with normal or borderline LVEF. In both crude and multivariable models, per 1-SD increment in EAT thickness was correlated with a higher risk of HF (crude hazard ratio [HR] 1.57, 95% CI 1.35–1.83; adjusted HR [95% CI], 1.43 [1.19–1.72]; both P < 0.001). The HR of covariates in multivariable models are exhibited in Additional file 1: Table S6. Compared to EAT < 9 mm, participants with EAT ≥ 9 mm had distinctly more cumulative events of HF (Fig. 2), and their risk of HF was significantly higher (crude HR [95% CI], 2.28 [1.51–3.46], P < 0.001; adjusted HR [95% CI], 1.55 [1.01–2.38], P = 0.045). Per 1-SD increment of EAT thickness was also found to correlate with a higher risk of AF (HR [95% CI], 1.16 [1.01–1.32], P = 0.030) in crude analysis, but insignificant in the multivariable model. No association was observed between EAT thickness and the risk of CHD. In addition, per 1-SD increment of EAT thickness was associated with a higher risk of MACE (crude HR [95% CI], 1.42 [1.26–1.59], P < 0.001; adjusted HR [95% CI], 1.23 [1.07–1.40], P = 0.003).

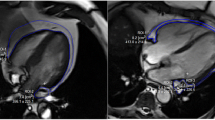

Mediation analysis

Precede to the mediation analysis, associations between the presupposed mediators (including biomarkers and cardiac measures) and the risk of HF were assessed. Of the 22 biomarkers and the cardiac measures (including LVEDD, LAID, LVWT, LVEF, GLS, and E/é) that were correlated with the risk of HF (Additional file 1: Table S7), CRP, GDF15, NT-proBNP, IGFBP2, LVEDD, LVWT, and GLS were detected to have a mediation effect for the association between EAT thickness and HF risk (Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S8). After fully adjusting, NT-proBNP and GLS still showed a robust mediation effect (Fig. 3). The direct effect (HR [95% CI], 1.51 [1.25–1.81], P < 0.001) between thicker EAT and higher risk of HF was weakened by the indirect effect through NT-proBNP (HR [95% CI], 0.95 [0.92–0.98], P = 0.011), resulting in a milder total effect (HR [95% CI], 1.43 [1.19–1.72], P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the direct effect (HR [95% CI], 1.39 [1.14–1.69], P = 0.001) between thicker EAT and higher risk of HF was strengthened by the indirect effect of GLS (HR [95% CI], 1.04 [1.01–1.07], P = 0.032), resulting in a greater total effect (HR [95% CI], 1.44 [1.18–1.76], P < 0.001).

NT-proBNP and GLS mediate the effect of EAT on the risk of heart failure. A Mediation effect of NT-proBNP. B Mediation effect of GLS. The total, direct, and indirect effects are expressed by hazard ratios. EAT, epicardial adipose tissue; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; GLS, global longitudinal strain; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.001. aAdjusted for sex, age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, and dyslipidemia

Discussion

In a large community-based sample, we observed that (i) EAT thickness was correlated with 14 circulating biomarkers including NT-proBNP, as well as the dimension, wall thickness, and myocardial strain of left ventricle; (ii) thickened EAT was associated with a higher risk of incident HF and the outcome composited by myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, HF, or death from CVD; and (iii) NT-proBNP and GLS had a mediation effect for the association between EAT thickness and HF risk.

As a well-recognized source of pro-inflammatory cytokines affecting the biochemical processes involved in cardiac dysfunction, EAT releases leptin, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, ANGPTL2, visfatin, adiponectin, resistin, omentin, and other bioactive molecules [1, 21]. Some of those, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1, were associated with myocardial collagen deposition and fibrosis [21, 22]. Biomarkers related to myocardial injury such as creatine kinase-MB, troponin T, and glycated hemoglobin were reported to be positively correlated with epicardial fat volume in patients with HFpEF or HF with mid-range ejection fraction [9, 23]. Our study identified additional CVD and metabolic syndrome-related markers that were associated with EAT thickness. Consistent with the prior studies, NT-proBNP showed an inverse correlation with EAT [9, 13]. Given that NT-proBNP is usually lower in HFpEF than in HFrEF patients for any given LV filling pressure, thicker EAT might tend to endorse the occurrence of HFpEF [24]. Besides, our results indicated that IGFBP1 and IGFBP2 negatively correlated with EAT thickness. IGFBP1 and IGFBP2 alter the interaction of insulin-like growth factors with their cell surface receptors, while insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling is a key pathway that governs EAT formation by redirecting the fate of Wt1 + lineage cells [2].

As a risk factor in the general population, EAT was found to correlate with the risk of incident HF and the composite outcome of MACE in our study. In prior cross-sectional analyses, peri-atrial and peri-coronary EAT were related to the development of AF and coronary atherosclerosis, respectively [4, 5, 25]. In a longitudinal study, EAT volume was also positively related to the duration and recurrence of AF [26]. The impact of EAT on the risk of AF might result from the electroanatomical dysregulation and wall fibrosis caused by the EAT surrounding the left atrium [3]. From the above, we could tell that EAT is not equally distributed throughout the heart and its function is regionally dependent. EAT in different locations has diverse transcriptome and proteome, which influence the near heart structures in different ways [27,28,29]. Since the EAT measured in this study was adjacent to the right ventricle, it is explainable that we failed to prove the relevancy between EAT thickness and the risk of incident CHD or AF. In the non-HF population, increased EAT has been proven to link with HFpEF development and a higher overall risk of cardiovascular adverse events in patients with CHD [7, 8]. Herein, we added that EAT thickness also correlated with the risk of HF in the community. Moreover, increase right ventricle localized EAT was associated with a higher risk of frequent ventricular premature beats [30]. Collectively, the promotion on both myocardial remodeling and arrhythmogenesis of EAT was suggested.

Patients with HFpEF displayed thicker EAT than non-HF controls and HF patients with reduced or mid-range ejection fraction [9, 10, 23]. And actually, HFrEF patients tended to have thinner EAT than controls [9, 31, 32]. This stressed the importance of EAT in the development of HFpEF. In HFpEF, increased EAT thickness is associated with worse GLS of both LA and LV, higher right-sided filling pressures, worse peak oxygen consumption and peripheral extraction, and higher mortality and HF hospitalization [9,10,11,12, 33]. These associations regarding cardiac function, hemodynamic status, and survival were weaker or absent, even opposite in HFrEF [9, 10, 33]. Moreover, greater EAT mass in HFpEF was associated with higher cardiac extracellular volume, which indicated more distinct myocardial fibrosis [33]. Among obese HFpEF patients with increased EAT, more concentric left ventricular remodeling, greater elevation in cardiac filling pressures, and worse exercise capacity were observed compared with non-obese HFpEF patients and non-HF controls [13].

EAT can affect the risk and severity of HFpEF via several mechanisms, such as increased mechanical restraint, inflammation, fibrosis, and autonomic dysregulation. The pro-inflammatory secretome of EAT is involved in endothelial function, extracellular matrix remodeling, coagulation, immune signaling, and apoptosis [29]. EAT/miRNA axis was also involved as a new pathological mechanism, explaining the adverse myocardial remodeling occurring after MI [6]. The gene expression pattern of peri-atrial EAT was related to cardiac muscle contraction and intracellular calcium signaling pathway [27]. Moreover, there exists a vicious circle created by the promotion of systemic inflammation on the accumulation of EAT [34]. Among the biochemical alterations caused by thickened EAT, the reduction of natriuretic peptide is likely to play a critical role in the development of HFpEF. Attenuated activation of natriuretic peptide signaling decreases the secretion of adiponectin and promotes adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac fibrosis [34]. Natriuretic peptide signaling also contributes to the changes in EAT metabolism in cardiac cachexia [35]. In the present study, a lower level of BNP which related to thicker EAT mediated a decreasing risk of HF in the general population, and this might be attributed to the accelerated breakdown of natriuretic peptides in people at risk of HFpEF [36].

Increased EAT thickness changes myocardial energy metabolism. In substrate utilization, it causes increased oxygen consumption, impaired oxygen use, and increased dependence on fatty acid oxidation [13]. It may also increase the ATP transfer rate through creatine kinase to compensate for depleted energy stores, exhibited by a saturated ATP shuttling in cardiomyocytes, and thus contributes to a reduction in the ability to enhance energy utilization under stress conditions [37]. In addition, the right ventricle might be particularly affected by EAT on account that approximately 75% of EAT resides over the right ventricle [38]. The pericardial restraint caused by EAT accumulation might facilitate right ventricular–arterial uncoupling, resulting in enhanced systolic ventricular interdependence and increased extravascular lung water, especially in HFpEF [13, 19, 39].

EAT provides an unconventional perspective on the pathophysiology of HF and other CVDs. Our findings supported the idea that EAT accumulation might alter the myocardial microenvironment and ultimately promote the fibrosis and stiffening of the myocardium, leading to myocardial remodeling and HF. Since the relationships between EAT thickness and prognosis in patients with HFpEF versus HFrEF were almost opposing in many situations, further studies are needed to specify the divergent roles of EAT in the pathophysiology of HF with different LVEF stratification [9, 10, 33]. Overall, indexes of EAT might solely, or joined with other metabolic parameters, become a tool for assessing the CVD risk in the general population. Since EAT can also be assessed by echocardiography with the most ready availability and lowest cost, a relatively ideal cost-effectiveness could be realized. In the meantime, EAT is a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor that has been shown to be regulated by lifestyle changes and pharmacological interventions. Thus, EAT could become a new therapeutic target of cardiometabolic diseases. Meta-analysis revealed that significant EAT reduction occurred with diet control and bariatric surgery but not with exercise, and the response to lifestyle changes was associated with higher secretion of adiponectin and leptin and decreased expression of pro-inflammatory adipokines [40]. Statins, metformin, and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce the quantity of EAT and to ameliorate its local pro-inflammatory effects and the influence on metabolic dysregulation [34, 41]. Still, it needs to be further investigated whether these therapies indeed improve outcomes through targeting at EAT and their heterogeneity in HF patients with different ejection fractions.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a significant prognostic role of EAT in the general population, rather than in patients with specific CVD. And we identified the mediators NT-proBNP and GLS between EAT and the risk of HF, suggesting the potential biochemical and mechanistic links between them. However, due to the retrospective nature of the present analysis, causality cannot be deduced. Besides, there were a limited number of incident HF cases, which might influence the estimates from the regression models. CMR was used in this study, providing greater precision and accuracy to quantify EAT thickness than echocardiography, whereas late gadolinium enhancement and evaluation of incidental intramyocardial fatty infiltration were not available, which could provide more prognostic information. In addition, the current study only assessed the thickness, not the volume, mass, or quality of EAT, and measured EAT only over the right ventricular free wall. Other limitations included that the participants were not multi-racial, resulting in the inadequacy of representativeness. At last, we failed to distinguish the classification of LVEF of all the participants who developed HF in the follow-up; thus, we could not determine whether the long-term risk related to thickening EAT is more predisposed to a specific type of HF.

Conclusions

In the general population, EAT thickness was correlated with inflammation and fibrosis-related circulating biomarkers, cardiac concentric change, myocardial strain impairment, incident HF risk, and overall CVD risk. NT-proBNP and GLS might partially mediate the effect of thickened EAT on the risk of HF. EAT could refine the assessment of CVD risk and become a new therapeutic target of cardiometabolic diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the Framingham Heart Study is available via reasonable request to the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the USA.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMR:

-

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- E/é :

-

Mitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity

- EAT:

-

Epicardial adipose tissue

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FHS:

-

Framingham Heart Study

- GLS:

-

Global longitudinal strain

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- HFpEF:

-

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF:

-

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- LAID:

-

Left atrial internal dimension

- LVEDD:

-

Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVWT:

-

Left ventricular wall thickness

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular event

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

References

Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:363–71.

Zangi L, Oliveira MS, Ye LY, Ma Q, Sultana N, Hadas Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor-dependent pathway drives epicardial adipose tissue formation after myocardial injury. Circulation. 2017;135:59–72.

Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:593–606.

Cosson E, Nguyen MT, Rezgani I, Berkane N, Pinto S, Bihan H, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue volume and myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic people living with diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:224.

de Vos AM, Prokop M, Roos CJ, Meijs MFL, van der Schouw YT, Rutten A, et al. Peri-coronary epicardial adipose tissue is related to cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcification in post-menopausal women. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:777–83.

Hao S, Sui X, Wang J, Zhang J, Pei Y, Guo L, et al. Secretory products from epicardial adipose tissue induce adverse myocardial remodeling after myocardial infarction by promoting reactive oxygen species accumulation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:848.

Morales-Portano JD, Peraza-Zaldivar JÁ, Suárez-Cuenca JA, Aceves-Millán R, Amezcua-Gómez L, Ixcamparij-Rosales CH, et al. Echocardiographic measurements of epicardial adipose tissue and comparative ability to predict adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34:1429–37.

Mahabadi AA, Anapliotis V, Dykun I, Hendricks S, Al-Rashid F, Lüdike P, et al. Epicardial fat and incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2022;357:140–5.

Pugliese NR, Paneni F, Mazzola M, De Biase N, Del Punta L, Gargani L, et al. Impact of epicardial adipose tissue on cardiovascular haemodynamics, metabolic profile, and prognosis in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1858–71.

Jin X, Hung C-L, Tay WT, Soon D, Sim D, Sung K-T, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue related to left atrial and ventricular function in heart failure with preserved versus reduced and mildly reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:1346–56.

van Woerden G, van Veldhuisen DJ, Manintveld OC, van Empel VPM, Willems TP, de Boer RA, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and outcome in heart failure with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15.

Gorter TM, van Woerden G, Rienstra M, Dickinson MG, Hummel YM, Voors AA, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and invasive hemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2020;8:667–76.

Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2017;136:6–19.

Andersson C, Nayor M, Tsao CW, Levy D, Vasan RS. Framingham Heart Study: JACC Focus Seminar, 1/8. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:2680–92.

Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Assael F, Vecci E, Tiberti C, Zappaterreno A, et al. Echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue is related to anthropometric and clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome: a new indicator of cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5163–8.

Gać P, Macek P, Poręba M, Kornafel-Flak O, Mazur G, Poręba R. Thickness of epicardial and pericoronary adipose tissue measured using 128-slice MSCT as predictors for risk of significant coronary artery diseases. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;190:555–66.

Flüchter S, Haghi D, Dinter D, Heberlein W, Kühl HP, Neff W, et al. Volumetric assessment of epicardial adipose tissue with cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:870–8.

Ho JE, McCabe EL, Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Tsao C, et al. Cardiometabolic traits and systolic mechanics in the community. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10.

Koepp KE, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Olson TP, Borlaug BA. Hemodynamic and functional impact of epicardial adipose tissue in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2020;8:657–66.

Huang Y-T, Yang H-I. Causal mediation analysis of survival outcome with multiple mediators. Epidemiology. 2017;28:370–8.

Abe I, Teshima Y, Kondo H, Kaku H, Kira S, Ikebe Y, et al. Association of fibrotic remodeling and cytokines/chemokines content in epicardial adipose tissue with atrial myocardial fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1717–27.

Kadomatsu T, Endo M, Miyata K, Oike Y. Diverse roles of ANGPTL2 in physiology and pathophysiology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:245–54.

van Woerden G, Gorter TM, Westenbrink BD, Willems TP, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstra M. Epicardial fat in heart failure patients with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1559–66.

Tanase DM, Radu S, Al Shurbaji S, Baroi GL, Florida Costea C, Turliuc MD, et al. Natriuretic peptides in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: from molecular evidences to clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E2629.

Batal O, Schoenhagen P, Shao M, Ayyad AE, Van Wagoner DR, Halliburton SS, et al. Left atrial epicardial adiposity and atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:230–6.

Wong CX, Abed HS, Molaee P, Nelson AJ, Brooks AG, Sharma G, et al. Pericardial fat is associated with atrial fibrillation severity and ablation outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1745–51.

Gaborit B, Venteclef N, Ancel P, Pelloux V, Gariboldi V, Leprince P, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue has a specific transcriptomic signature depending on its anatomical peri-atrial, peri-ventricular, or peri-coronary location. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;108:62–73.

Zhao L, Guo Z, Wang P, Zheng M, Yang X, Liu Y, et al. Proteomics of epicardial adipose tissue in patients with heart failure. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:511–20.

McAninch EA, Fonseca TL, Poggioli R, Panos AL, Salerno TA, Deng Y, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue has a unique transcriptome modified in severe coronary artery disease. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:1267–78.

Tam W-C, Lin Y-K, Chan W-P, Huang J-H, Hsieh M-H, Chen S-A, et al. Pericardial fat is associated with the risk of ventricular arrhythmia in Asian patients. Circ J. 2016;80:1726–33.

Doesch C, Haghi D, Flüchter S, Suselbeck T, Schoenberg SO, Michaely H, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:40.

Doesch C, Streitner F, Bellm S, Suselbeck T, Haghi D, Heggemann F, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:E253-261.

Tromp J, Bryant JA, Jin X, van Woerden G, Asali S, Yiying H, et al. Epicardial fat in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:835–8.

Packer M. Epicardial adipose tissue may mediate deleterious effects of obesity and inflammation on the myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2360–72.

Janovska P, Melenovsky V, Svobodova M, Havlenova T, Kratochvilova H, Haluzik M, et al. Dysregulation of epicardial adipose tissue in cachexia due to heart failure: the role of natriuretic peptides and cardiolipin. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11:1614–27.

Lanfear DE, Chow S, Padhukasahasram B, Li J, Langholz D, Tang WHW, et al. Genetic and nongenetic factors influencing pharmacokinetics of B-type natriuretic peptide. J Card Fail. 2014;20:662–8.

Rayner JJ, Peterzan MA, Watson WD, Clarke WT, Neubauer S, Rodgers CT, et al. Myocardial energetics in obesity: enhanced ATP delivery through creatine kinase with blunted stress response. Circulation. 2020;141:1152–63.

Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9 quiz 1417–8.

Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Wiley B, Koepp KE, Jorgenson CC, Egbe A, et al. The haemodynamic basis of lung congestion during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3721–30.

Rabkin SW, Campbell H. Comparison of reducing epicardial fat by exercise, diet or bariatric surgery weight loss strategies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:406–15.

Díaz-Rodríguez E, Agra RM, Fernández ÁL, Adrio B, García-Caballero T, González-Juanatey JR, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on human epicardial adipose tissue: modulation of insulin resistance, inflammatory chemokine production, and differentiation ability. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:336–46.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants, investigators, research coordinators, and committee members of the Framingham Heart Study.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81800344, 81800345, and 82000372) and the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2022A1515111120, 2020A1515010452, and 2020A1515011095).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Under the direction of WY and LC, CM, HY, and LW performed the study design, data extraction, and statistical analysis. HX and ZW repeated the analyses. PY provided technical support with respect to radiology and drew the diagrams. CM and HY wrote the original draft, while CC, LJ, WF, and DY revised the draft. All other authors checked the data to ensure accuracy and edited the manuscript prior to submission to ensure the standard English grammar. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects in the Framingham Heart Study had signed informed consent forms. Our current study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (Application ID: [2019]266).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Detailed diagnostic criteria of study outcomes. Table S2. Baseline right ventricle indexes according to EAT thickness. Table S3. The differences of the shortlisted 14 circulating biomarkers according to EAT thickness. Table S4. The associations of all 85 circulating biomarkers with EAT thickness. Table S5. Baseline characteristics according to occurrence of incident heart failure and LVEF stratification in those with incident heart failure. Table S6. The hazard ratio of EAT and adjusted factors in univariate and multivariate models which assessed their association with incident heart failure. Table S7. Associations of circulating biomarkers and cardiac measures with incident heart failure. Table S8. Mediation analyses of circulating biomarkers and cardiac measures in the association of EAT with the risk of heart failure.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Choy, M., Huang, Y., Peng, Y. et al. Association between epicardial adipose tissue and incident heart failure mediating by alteration of natriuretic peptide and myocardial strain. BMC Med 21, 117 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02836-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02836-4