Abstract

Background

Nurses turnover intention, representing the extent to which nurses express a desire to leave their current positions, is a critical global public health challenge. This issue significantly affects the healthcare workforce, contributing to disruptions in healthcare delivery and organizational stability. In Ethiopia, a country facing its own unique set of healthcare challenges, understanding and mitigating nursing turnover are of paramount importance. Hence, the objectives of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to determine the pooled proportion ofturnover intention among nurses and to identify factors associated to it in Ethiopia.

Methods

A comprehensive search carried out for studies with full document and written in English language through an electronic web-based search strategy from databases including PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, Google Scholar and Ethiopian University Repository online. Checklist from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was used to assess the studies’ quality. STATA version 17 software was used for statistical analyses. Meta-analysis was done using a random-effects method. Heterogeneity between the primary studies was assessed by Cochran Q and I-square tests. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were carried out to clarify the source of heterogeneity.

Result

This systematic review and meta-analysis incorporated 8 articles, involving 3033 nurses in the analysis. The pooled proportion of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia was 53.35% (95% CI (41.64, 65.05%)), with significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 97.9, P = 0.001). Significant association of turnover intention among nurses was found with autonomous decision-making (OR: 0.28, CI: 0.14, 0.70) and promotion/development (OR: 0.67, C.I: 0.46, 0.89).

Conclusion and recommendation

Our meta-analysis on turnover intention among Ethiopian nurses highlights a significant challenge, with a pooled proportion of 53.35%. Regional variations, such as the highest turnover in Addis Ababa and the lowest in Sidama, underscore the need for tailored interventions. The findings reveal a strong link between turnover intention and factors like autonomous decision-making and promotion/development. Recommendations for stakeholders and concerned bodies involve formulating targeted retention strategies, addressing regional variations, collaborating for nurse welfare advocacy, prioritizing career advancement, reviewing policies for nurse retention improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Turnover intention pertaining to employment, often referred to as the intention to leave, is characterized by an employee’s contemplation of voluntarily transitioning to a different job or company [1]. Nurse turnover intention, representing the extent to which nurses express a desire to leave their current positions, is a critical global public health challenge. This issue significantly affects the healthcare workforce, contributing to disruptions in healthcare delivery and organizational stability [2].

The global shortage of healthcare professionals, including nurses, is an ongoing challenge that significantly impacts the capacity of healthcare systems to provide quality services [3]. Nurses, as frontline healthcare providers, play a central role in patient care, making their retention crucial for maintaining the functionality and effectiveness of healthcare delivery. However, the phenomenon of turnover intention, reflecting a nurse’s contemplation of leaving their profession, poses a serious threat to workforce stability [4].

Studies conducted globally shows that high turnover rates among nurses in several regions, with notable figures reported in Alexandria (68%), China (63.88%), and Jordan (60.9%) [5,6,7]. In contrast, Israel has a remarkably low turnover rate of9% [8], while Brazil reports 21.1% [9], and Saudi hospitals26% [10]. These diverse turnover rates highlight the global nature of the nurse turnover phenomenon, indicating varying degrees of workforce mobility in different regions.

The magnitude and severity of turnover intention among nurses worldwide underscore the urgency of addressing this issue. High turnover rates not only disrupt healthcare services but also result in a loss of valuable skills and expertise within the nursing workforce. This, in turn, compromises the continuity and quality of patient care, with potential implications for patient outcomes and overall health service delivery [11]. Extensive research conducted worldwide has identified a range of factors contributing to turnover intention among nurses [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These factors encompass both individual and organizational aspects, such as high workload, inadequate support, limited career advancement opportunities, job satisfaction, conflict, payment or reward, burnout sense of belongingness to their work environment. The complex interplay of these factors makes addressing turnover intention a multifaceted challenge that requires targeted interventions.

In Ethiopia, a country facing its own unique set of healthcare challenges, understanding and mitigating nursing turnover are of paramount importance. The healthcare system in Ethiopia grapples with issues like resource constraints, infrastructural limitations, and disparities in healthcare access [18]. Consequently, the factors influencing nursing turnover in Ethiopia may differ from those in other regions. Previous studies conducted in the Ethiopian context have started to unravel some of these factors, emphasizing the need for a more comprehensive examination [18, 19].

Although many cross-sectional studies have been conducted on turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia, the results exhibit variations. The reported turnover intention rates range from a minimum of 30.6% to a maximum of 80.6%. In light of these disparities, this systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken to ascertain the aggregated prevalence of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. By systematically analyzing findings from various studies, we aimed to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing turnover intention specific to the Ethiopian healthcare context. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to answer the following research questions.

-

1.

What is the pooled prevalence of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia?

-

2.

What are the factors associated with turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia?

Objectives

The primary objective of this review was to assess the pooled proportion of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. The secondary objective was identifying the factors associated to turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and search strategy

A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted, examining observational studies on turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. The procedure for this systematic review and meta-analysis was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [20]. PRISMA-2015 statement was used to report the findings [21, 22]. This systematic review and meta-analysis were registered on PROSPERO with the registration number of CRD42024499119.

We conducted systematic and an extensive search across multiple databases, including PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, Google Scholar and Ethiopian University Repository online to identify studies reporting turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. We reviewed the database available at http://www.library.ucsf.edu and the Cochrane Library to ensure that the intended task had not been previously undertaken, preventing any duplication. Furthermore, we screened the reference lists to retrieve relevant articles. The process involved utilizing EndNote (version X8) software for downloading, organizing, reviewing, and citing articles. Additionally, a manual search for cross-references was performed to discover any relevant studies not captured through the initial database search. The search employed a comprehensive set of the following search terms:“prevalence”, “turnover intention”, “intention to leave”, “attrition”, “employee attrition”, “nursing staff turnover”, “Ethiopian nurses”, “nurses”, and “Ethiopia”. These terms were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR) to conduct a thorough and systematic search across the specified databases.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

The established inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis and systematic review are as follows to guide the selection of articles for inclusion in this review.

-

1.

Population: Nurses working in Ethiopia.

-

2.

Study period: studies conducted or published until 23November 2023.

-

3.

Study design: All observational study designs, such as cross-sectional, longitudinal, and cohort studies, were considered.

-

4.

Setting: Only studies conducted in Ethiopia were included.

-

5.

Outcome; turnover intention.

-

6.

Study: All studies, whether published or unpublished, in the form of journal articles, master’s theses, and dissertations, were included up to the final date of data analysis.

-

7.

Language: This study exclusively considered studies in the English language.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded were studies lacking full text or Studies with a Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) score of 6 or less. Studies failing to provide information on turnover intention among nurses or studies for which necessary details could not be obtained were excluded. Three authors (E.E., T.G., K.A) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved studies, other two authors (E.I & M.M) input sought for consensus on potential in- or exclusion.

Quality assessment and data extraction

Two authors (E.E, A.A, G.N) independently conducted a critical appraisal of the included studies. Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklists of prevalence study was used to assess the quality of the studies. Studies with a Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) score of seven or more were considered acceptable [23]. The tool has nine parameters, which have yes, no, unclear, and not applicable options [24]. Two reviewers (I.A, B.A) were involved when necessary, during the critical appraisal process. Accordingly, all studies were included in our review. (Table 1)Questions to evaluate the methodological quality of studies on turnover intention among nurses and its associated factors in Ethiopia are the followings:

Q1 = was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population?

Q2. Were study participants sampled appropriately.

Q3. Was the sample size adequate?

Q4. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail?

Q5. Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?

Q6. Were the valid methods used for the identification of the condition?

Q7. Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants?

Q8. Was there appropriate statistical analysis?

Q9. Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate.

managed appropriately?

Data was extracted and recorded in a Microsoft Excel as guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) data extraction form for observational studies. Three authors (E.E, M.G, T.T) independently conducted data extraction. Recorded data included the first author’s last name, publication year, study setting or country, region, study design, study period, sample size, response rate, population, type of management, proportion of turnover intention, and associated factors. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion between extractors.

Data processing and analysis

Data analysis procedures involved importing the extracted data into STATA 14 statistical software for conducting a pooled proportion of turnover intention among nurses. To evaluate potential publication bias and small study effects, both funnel plots and Egger’s test were employed [25, 26]. We used statistical tests such as the I statistic to quantify heterogeneity and explore potential sources of variability. Additionally, subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of specific study characteristics on the overall results. I2values of 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75% were interpreted as indicating no, low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively [27].

To assess publication bias, we employed several methods, including funnel plots and Egger’s test. These techniques allowed us to visually inspect asymmetry in the distribution of study results and statistically evaluate the presence of publication bias. Furthermore, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings to potential publication bias and other sources of bias.

Utilizing a random-effects method, a meta-analysis was performed to assess turnover intention among nurses, employing this method to account for observed variability [28]. Subgroup analyses were conducted to compare the pooled magnitude of turnover intention among nurses and associated factors across different regions. The results of the pooled prevalence were visually presented in a forest plot format with a 95% confidence interval.

Result

Study selection

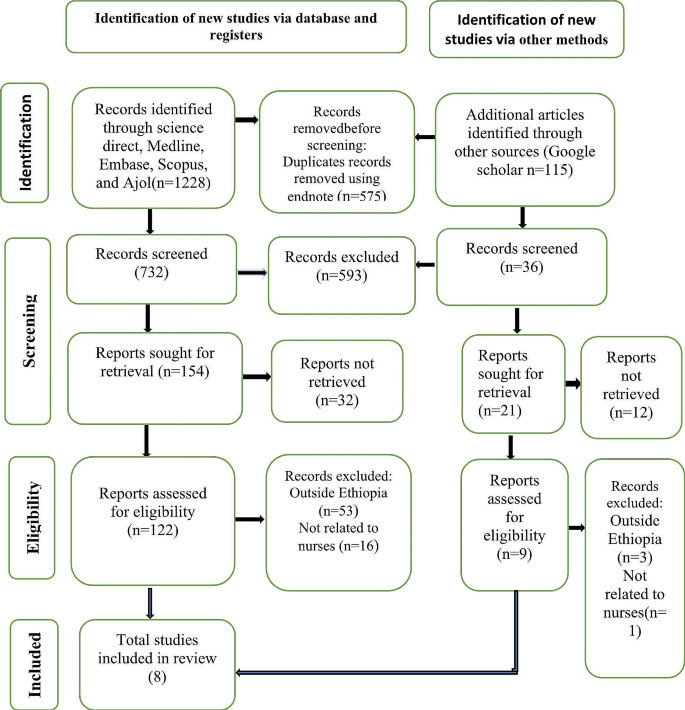

After conducting the initial comprehensive search concerning turnover intention among nurses through Medline, Cochran Library, Web of Science, Embase, Ajol, Google Scholar, and other sources, a total of 1343 articles were retrieved. Of which 575 were removed due to duplication. Five hundred ninety-three articles were removed from the remaining 768 articles by title and abstract. Following theses, 44 articles which cannot be retrieved were removed. Finally, from the remaining 131 articles, 8 articles with a total 3033 nurses were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

All included 8 studies had a cross-sectional design and of which, 2 were from Tigray region, 2 were from Addis Ababa(Capital), 1 from south region, 1 from Amhara region, 1 from Sidama region, and 1 was multiregional and Nationwide. The prevalence of turnover intention among nurses ‘ranges from 30.6 to 80.6%. Table 2.

Pooled prevalence of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia

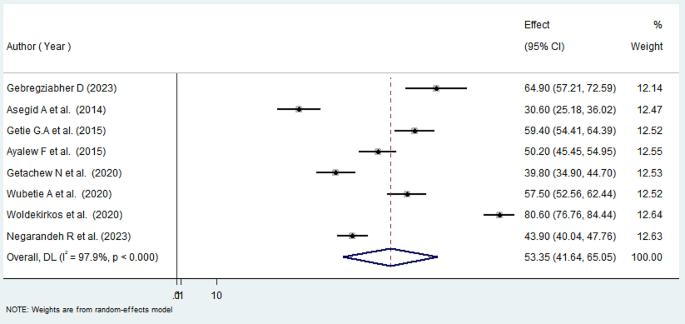

Our comprehensive meta-analysis revealed a notable turnover intention rate of 53.35% (95% CI: 41.64, 65.05%) among Ethiopian nurses, accompanied by substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 97.9, P = 0.000) as depicted in Fig. 2. Given the observed variability, we employed a random-effects model to analyze the data, ensuring a robust adjustment for the significant heterogeneity across the included studies.

Subgroup analysis of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia

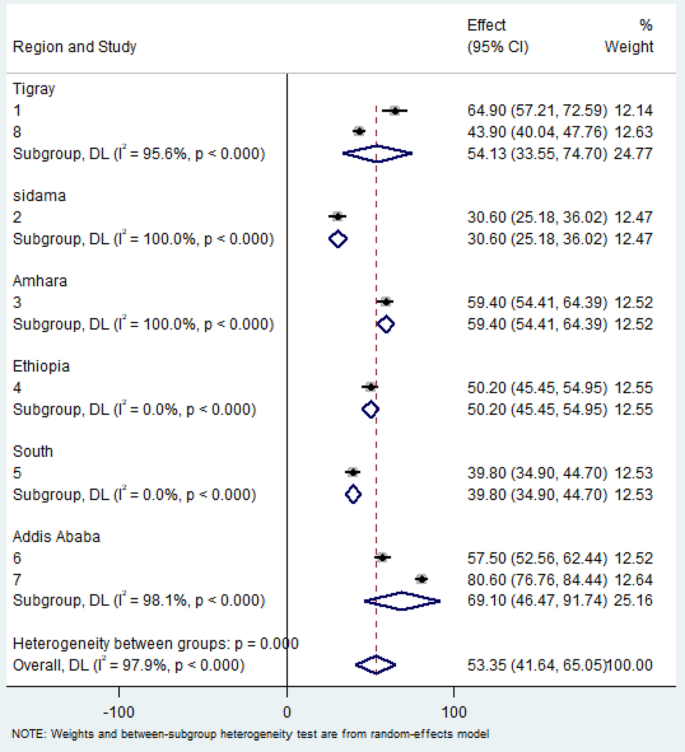

To address the observed heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on regions. The results of the subgroup analysis highlighted considerable variations, with the highest level of turnover intention identified in Addis Ababa at 69.10% (95% CI: 46.47, 91.74%) and substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98.1%). Conversely, the Sidama region exhibited the lowest level of turnover intention among nurses at 30.6% (95% CI: 25.18, 36.02%), accompanied by considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 100.0%) (Fig. 3).

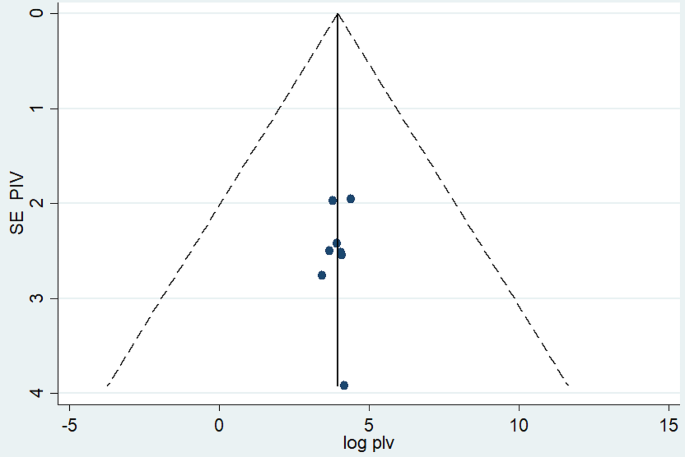

Publication bias of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia

The Egger’s test result (p = 0.64) is not statistically significant, indicating no evidence of publication bias in the meta-analysis (Table 3). Additionally, the symmetrical distribution of included studies in the funnel plot (Fig. 4) confirms the absence of publication bias across studies.

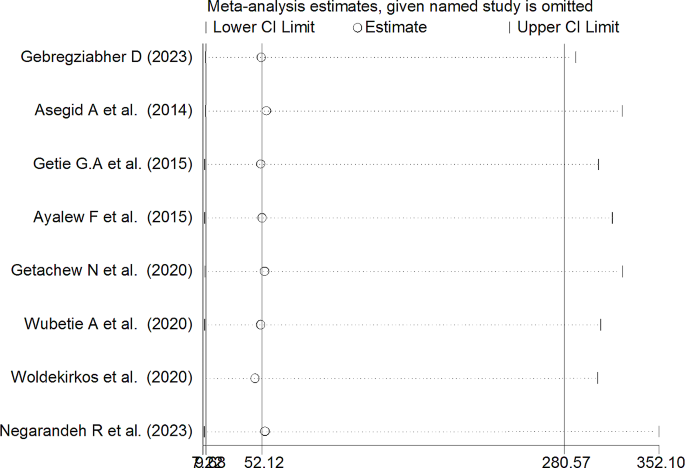

Sensitivity analysis

The leave-out-one sensitivity analysis served as a meticulous evaluation of the influence of individual studies on the comprehensive pooled prevalence of turnover intention within the context of Ethiopian nurses. In this systematic process, each study was methodically excluded from the analysis one at a time. The outcomes of this meticulous examination indicated that the exclusion of any particular study did not lead to a noteworthy or statistically significant alteration in the overall pooled estimate of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. The findings are visually represented in Fig. 5, illustrating the stability and robustness of the overall pooled estimate even with the removal of specific studies from the analysis.

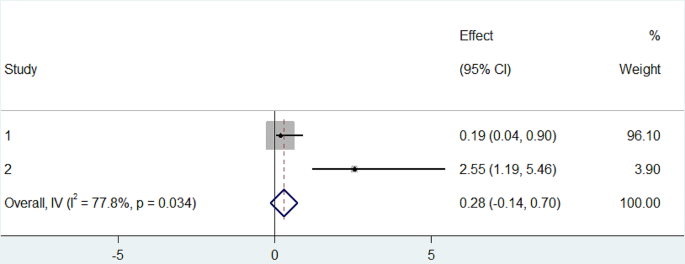

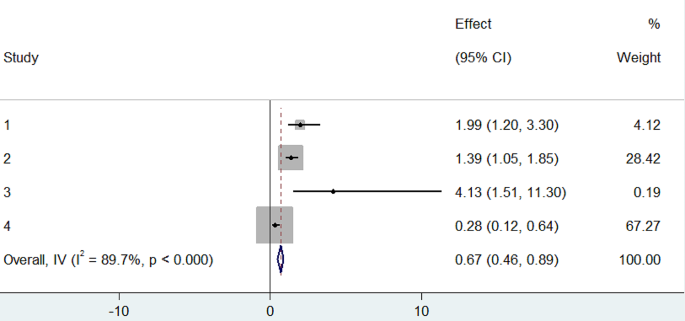

Factors associated with turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia

In our meta-analysis, we comprehensively reviewed and conducted a meta-analysis on the determinants of turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia by examining eight relevant studies [6, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. We identified a significant association between turnover intention with autonomous decision-making (OR: 0.28, CI: 0.14, 0.70) (Fig. 6) and promotion/development (OR: 0.67, CI: 0.46, 0.89) (Fig. 7). In both instances, the odds ratios suggest a negative association, signifying that increased levels of autonomous decision-making and promotion/development were linked to reduced odds of turnover intention.

Discussion

In our comprehensive meta-analysis exploring turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia, our findings revealed a pooled proportion of turnover intention at 53.35%. This significant proportion warrants a comparative analysis with turnover rates reported in other global regions. Distinct variations emerge when compared with turnover rates in Alexandria (68%), China (63.88%), and Jordan (60.9%) [5,6,7]. This comparison highlights that the multifaceted nature of turnover intention, influenced by diverse contextual, cultural, and organizational factors. Conversely, Ethiopia’s turnover rate among nurses contrasts with substantially lower figures reported in Israel (9%) [8], Brazil (21.1%) [9], and Saudi hospitals (26%) [10]. Challenges such as work overload, economic constraints, limited promotional opportunities, lack of recognition, and low job rewards are more prevalent among nurses in Ethiopia, contributing to higher turnover intention compared to their counterparts [7, 29, 36].

The highest turnover intention was observed in Addis Ababa, while Sidama region displayed the lowest turnover intention among nurses, These differences highlight the complexity of turnover intention among Ethiopian nurses, showing the importance of specific interventions in each region to address unique factors and improve nurses’ retention.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis in the Ethiopian nursing context revealed a significant inverse association between turnover intention and autonomous decision-making. The odd of turnover intention is approximately reduced by 72% in employees with autonomous decision-making compared to those without autonomous decision-making. This finding was supported by other similar studies conducted in South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, and Turkey [37,38,39,40].

The significant association of turnover intention with promotion/development in our study underscores the crucial role of career advancement opportunities in alleviating turnover intention among nurses. Specifically, our analysis revealed that individuals with promotion/development had approximately 33% lower odds of turnover intention compared to those without such opportunities. These results emphasize the pivotal influence of organizational support in shaping the professional environment for nurses, providing substantive insights for the formulation of evidence-based strategies targeted at enhancing workforce retention. This finding is in line with former researches conducted in Taiwan, Philippines and Italy [41,42,43].

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis on turnover intention among Ethiopian nurses reveals a considerable challenge, with a pooled proportion of 53.35%. Regional variations highlight the necessity for region-specific strategies, with Addis Ababa displaying the highest turnover intention and Sidama region the lowest. A significant inverse association was found between turnover intention with autonomous decision-making and promotion/development. These insights support the formulation of evidence-based strategies and policies to enhance nurse retention, contributing to the overall stability of the Ethiopian healthcare system.

Recommendations

Federal ministry of health (FMoH)

The FMoH should consider the regional variations in turnover intention and formulate targeted retention strategies. Investment in professional development opportunities and initiatives to enhance autonomy can be integral components of these strategies.

Ethiopian nurses association (ENA)

ENA plays a pivotal role in advocating for the welfare of nurses. The association is encouraged to collaborate with healthcare institutions to promote autonomy, create mentorship programs, and advocate for improved working conditions to mitigate turnover intention.

Healthcare institutions

Hospitals and healthcare facilities should prioritize the provision of career advancement opportunities and recognize the value of professional autonomy in retaining nursing staff. Tailored interventions based on regional variations should be considered.

Policy makers

Policymakers should review existing healthcare policies to identify areas for improvement in nurse retention. Policy changes that address challenges such as work overload, limited promotional opportunities, and economic constraints can positively impact turnover rates.

Future research initiatives

Further research exploring the specific factors contributing to turnover intention in different regions of Ethiopia is recommended. Understanding the nuanced challenges faced by nurses in various settings will inform the development of more targeted interventions.

Strength and limitations

Our systematic review and meta-analysis on nurse turnover intention in Ethiopia present several strengths. The comprehensive inclusion of diverse studies provides a holistic view of the issue, enhancing the generalizability of our findings. The use of a random-effects model accounts for potential heterogeneity, ensuring a more robust and reliable synthesis of data.

However, limitations should be acknowledged. The heterogeneity observed across studies, despite the use of a random-effects model, may impact the precision of the pooled estimate. These considerations should be taken into account when interpreting and applying the results of our analysis.

Data availability

Data set used on this analysis will available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ENA:

-

Ethiopian Nurses Association

- FMoH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis Protocols

References

Kanchana L, Jayathilaka R. Factors impacting employee turnover intentions among professionals in Sri Lankan startups. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(2):e0281729.

Boateng AB, et al. Factors influencing turnover intention among nurses and midwives in Ghana. Nurs Res Pract. 2022;2022:4299702.

Organization WH. WHO Guideline on Health Workforce Development Attraction, Recruitment and Retention in Rural and Remote Areas, 2021, pp. 1-104.

Hayes LJ, et al. Nurse turnover: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):237–63.

Yang H, et al. Validation of work pressure and associated factors influencing hospital nurse turnover: a cross-sectional investigation in Shaanxi Province, China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–11.

Ayalew E et al. Nurses’ intention to leave their job in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 2021. 7(6).

Al Momani M. Factors influencing public hospital nurses’ intentions to leave their current employment in Jordan. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4(6):1847–53.

DeKeyser Ganz F, Toren O. Israeli nurse practice environment characteristics, retention, and job satisfaction. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2014;3(1):1–8.

de Oliveira DR, et al. Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):21.

Dall’Ora C, et al. Association of 12 h shifts and nurses’ job satisfaction, burnout and intention to leave: findings from a cross-sectional study of 12 European countries. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008331.

Lu H, Zhao Y, While A. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:21–31.

Ramoo V, Abdullah KL, Piaw CY. The relationship between job satisfaction and intention to leave current employment among registered nurses in a teaching hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(21–22):3141–52.

Al Sabei SD, et al. Nursing work environment, turnover intention, Job Burnout, and Quality of Care: the moderating role of job satisfaction. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(1):95–104.

Wang H, Chen H, Chen J. Correlation study on payment satisfaction, psychological reward satisfaction and turnover intention of nurses. Chin Hosp Manag. 2018;38(03):64–6.

Loes CN, Tobin MB. Interpersonal conflict and organizational commitment among licensed practical nurses. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2018;37(2):175–82.

Wei H, et al. The state of the science of nurse work environments in the United States: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018;5(3):287–300.

Nantsupawat A, et al. Effects of nurse work environment on job dissatisfaction, burnout, intention to leave. Int Nurs Rev. 2017;64(1):91–8.

Ayalew F, et al. Factors affecting turnover intention among nurses in Ethiopia. World Health Popul. 2015;16(2):62–74.

Debie A, Khatri RB, Assefa Y. Contributions and challenges of healthcare financing towards universal health coverage in Ethiopia: a narrative evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):866.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Reviews. 2015;4(1):1–9.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Moher D et al. Group, P.-P.(2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement.

Institute JB. Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Checkl prevalance Stud [Internet]. 2016;7.

Sakonidou S, et al. Interventions to improve quantitative measures of parent satisfaction in neonatal care: a systematic review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4(1):e000613.

Egger M, Smith GD. Meta-analysis: potentials and promise. BMJ. 1997;315(7119):1371.

Tura G, Fantahun M, Worku A. The effect of health facility delivery on neonatal mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:18.

Lin L. Comparison of four heterogeneity measures for meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(1):376–84.

McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):812–22.

Asegid A, Belachew T, Yimam E. Factors influencing job satisfaction and anticipated turnover among nurses in Sidama zone public health facilities, South Ethiopia Nursing research and practice, 2014. 2014.

Wubetie A, Taye B, Girma B. Magnitude of turnover intention and associated factors among nurses working in emergency departments of governmental hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institutional based study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:97.

Getie GA, Betre ET, Hareri HA. Assessment of factors affecting turnover intention among nurses working at governmental health care institutions in east Gojjam, Amhara region, Ethiopia, 2013. Am J Nurs Sci. 2015;4(3):107–12.

Gebregziabher D, et al. The relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses in Axum comprehensive and specialized hospital Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):79.

Negarandeh R et al. Magnitude of nurses’ intention to leave their jobs and its associated factors of nurses working in tigray regional state, north ethiopia: cross sectional study 2020.

Nigussie Bolado G, et al. The magnitude of turnover intention and Associated factors among nurses working at Governmental Hospitals in Southern Ethiopia: a mixed-method study. Nursing: Research and Reviews; 2023. pp. 13–29.

Woldekiros AN, Getye E, Abdo ZA. Magnitude of job satisfaction and intention to leave their present job among nurses in selected federal hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(6):e0269540.

Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):698.

Lewis M. Causal factors that influence turnover intent in a manufacturing organisation. University of Pretoria (South Africa); 2008.

Kuria S, Alice O, Wanderi PM. Assessment of causes of labour turnover in three and five star-rated hotels in Kenya International journal of business and social science, 2012. 3(15).

Blaauw D, et al. Comparing the job satisfaction and intention to leave of different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa. Global Health Action. 2013;6(1):19287.

Masum AKM, et al. Job satisfaction and intention to quit: an empirical analysis of nurses in Turkey. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1896.

Song L. A study of factors influencing turnover intention of King Power Group at Downtown Area in Bangkok, Thailand. Volume 2. International Review of Research in Emerging Markets & the Global Economy; 2016. 3.

Karanikola MN, et al. Moral distress, autonomy and nurse-physician collaboration among intensive care unit nurses in Italy. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(4):472–84.

Labrague LJ, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Tsaras K. Predictors and outcomes of nurse professional autonomy: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25(1):e12711.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.E. conceptualized the study, designed the research, performed statistical analysis, and led the manuscript writing. I.A, T.G, M.M contributed to the study design and provided critical revisions. K.A., G.N, B.A., E.I., and T.T. participated in data extraction and quality assessment. M.M. and T.G. K.A. and G.N. contributed to the literature review. I.A, A.A. and B.A. assisted in data interpretation. E.I. and T.T. provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval and informed consent are not required, as this study is a systematic review and meta-analysis that only involved the use of previously published data.

Ethical guidelines

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Elfios, E., Asale, I., Merkine, M. et al. Turnover intention and its associated factors among nurses in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 662 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11122-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11122-9