Abstract

Background

One crucial obstacle to attaining universal immunization coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa is the paucity of timely and high-quality data. This challenge, in part, stems from the fact that many frontline immunization staff in this part of the world are commonly overburdened with multiple data-related responsibilities that often compete with their clinical tasks, which in turn could affect their data collection practices. This study assessed the data management practices of immunization staff and unveiled potential barriers impacting immunization data quality in Cameroon.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted, involving health districts and health facilities in all 10 regions in Cameroon selected by a multi-stage sampling scheme. Structured questionnaires and observation checklists were used to collect data from Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) staff, and data were analyzed using STATA VERSION 13.0 (StataCorp LP. 2015. College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 265 facilities in 68 health districts were assessed. There was limited availability of some data recording tools like vaccination cards (43%), maintenance registers (8%), and stock cards (57%) in most health facilities. Core data collection tools were incompletely filled in a significant proportion of facilities (37% for registers and 81% for tally sheets). Almost every health facility (89%) did not adhere to the recommendation of filling tally sheets during vaccination; the filling was instead done either before (51% of facilities) or after (25% of facilities) vaccinating several children. Moreso, about 8% of facilities did not collect data on vaccine administration. About a third of facilities did not collect data on stock levels (35%), vaccine storage temperatures (21%), and vaccine wastage (39%).

Conclusion

Our findings unveil important gaps in data collection practices at the facility level that could adversely affect Cameroon’s immunization data quality. It highlights the urgent need for systematic capacity building of frontline immunization staff on data management capacity, standardizing data management processes, and building systems that ensure constant availability of data recording tools at the facility level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Estimates suggest that between 2010 and 2019, immunization alone has prevented over 37 million deaths globally [1, 2]. Moreso, immunization brings added value to communities by reducing families’ health expenditures and improving countries’ productivity and resilience. For example, some studies have reported that immunization returns an estimated US$16 for every US$ 1 invested, and this return can reach US$44 when broader social and economic benefits or vaccination are considered [3, 4]. But despite these benefits, national and subnational vaccination coverage rates have plateaued in several countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where coverage rates for basically all antigens are considerably lowered compared to other regions [1].

One key contributing factor to the above phenomenon is the paucity of timely and high-quality immunization data. Indeed, in many settings, existing data systems can rarely guarantee the generation of timely and good-quality data at all health system levels - a weakness that can have dire consequences on various aspects of immunization [5, 6]. For instance, inadequate immunization data quality can lead to missed opportunities to identify under-immunized or zero-dose children, poor defaulter tracking, and inaccurate vaccine coverage estimation [6]. This, in turn, could undermine national and international investments and increase the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD) by failing to identify populations with low vaccination coverage [7].

Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance made data quality a strategic focus area in 2015, highlighting quality immunization data as a ‘critical enabler’ to achieving immunization targets [8, 9]. Yet, poor immunization data quality continues to be a pervasive problem across many Gavi-eligible countries. For example, a study assessing the validity of reported vaccination coverage in 45 Gavi-eligible countries found that 75.5% of officially reported coverage figures from administrative sources were at least 10% higher than national survey estimates [10]. Similarly, in a study evaluating the quality of immunization monitoring systems in 27 Gavi-supported countries (including Cameroon), Ronveaux et al in 2005 reported that only 60% of health units had data recording forms (immunization registers and tally sheets) available for a whole year, and that only 59% of health workers completed a vaccination card properly [11]. Similarly, a study carried out in North-West Ethiopia noted that nearly half of all surveyed health facilities did not have standardized immunization registers and tally sheets available [12]. Lack of critical immunization data collections tools as well as inadequate data recording practices invariably affects a country’s immunization coverage estimates.

In Cameroon, remarkable progress has been made to improve national immunization coverage, since the inception of Cameroon’s Expanded program on immunization [13]. However, despite making noteworthy progress, coverage rates for many antigens still fall below set targets [14, 15]. A few studies have attempted to examine the performance of different components of Cameroon’s immunization system [16,17,18,19,20,21], exploring possible barriers and facilitators to optimal immunization coverage. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published study evaluating the data management practices of frontline immunization staff in Cameroon. This study was, therefore, designed to assess the data management practices of immunization staff in healthcare facilities, and it unveiled several barriers to high-quality and timely immunization data in Cameroon.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional facility-based study carried out as part of a national baseline assessment to identify and describe factors contributing to declining immunization coverage in Cameroon.

Study setting

The study was conducted in Cameroon, a country located in Central Africa, at the Gulf of Guinea, with a population of approximately 28 million inhabitants, and covering a total surface area of 475,440 km2 [22]. The country is divided into 10 administrative regions, namely Adamawa (AD), Centre (CE), East (ES), Far-North (EN), Littoral (LT), North (NO), North-West (NW), West (OU), South (SU) and South-West (SW) regions [23].

Cameroon’s health sector is organized into three main levels (central, intermediate, and peripheral), with each level having specific competencies, administrative, health and dialogue structures [24]. The central level is headed by the ministry of public health and focuses mainly on the development of policies, strategies, and coordination. The intermediate level is headed by the 10 regional delegations and this level provide technical support to the country’s 189 health districts. The health districts, in turn, are mainly responsible for delivering primary health care services to the Cameroonian population. Preventive services such as immunization services are incorporated into all levels of the health system [25].

Immunization performance monitoring is achieved through a hierarchical administrative data monitoring system. Focal EPI staff at health facilities aggregate data on monthly tally sheets into paper-based monthly activity report, which are then transmitted to the district data management team for entry into the District Health Information System (DHIS2). Immunization data in the DHIS2 are then aggregated at a regional level before transmission to national level for national estimates of coverages for various indicators [26].

Sampling

A minimum sample size of 145 health facilities was estimated using the following formula and parameters.

Design effect (DEFF) of 1.5, Critical value (Z) of 1.96 for a confidence level of 95%, estimated proportion of outcome (p) = 50%, and margin of error (E) of 10%.

Multistage sampling was used after allocating the number of districts and health facilities to be selected. The number of districts was allocated in proportion to the total number of districts per region, in the ten regions. Then, the number of urban and rural districts were assigned within each region based on the region-specific breakdown and health facilities allocated across regions in proportion to the national distribution.

The districts were then randomly selected within specified region urban or rural strata in the first stage and health facilities were randomly selected within the identified rural/urban districts in the second stage. This was done while ensuring that the same number of facilities was selected within each district in a region.

Study procedures

Trainings

Trainings were carried out in all regions by members of the baseline assessment management team to provide regional supervisors and assessors with the necessary knowledge and skills to undertake the baseline assessment. Trainings lasted a minimum of two days and consisted of theoretical presentations and practical sessions on data collection, entry, and transmission processes.

Data collection

Data collection plans for targeted districts and health facilities were developed by the baseline assessment management team and the regional EPI teams prior to data collection. To prevent unproductive visits during data collection, assessors contacted the health facilities via phone to remind them of planned visits. Upon arrival in facilities, the purpose of the assessment was explained to the facility head, or their representative and the health facility focal EPI staff interviewed. Additionally, an ongoing fixed-post vaccination session was observed, and vaccination data collection tools were physically inspected.

Study tools

The tools used for this study included health facility questionnaire, (which was designed to assess immunization data collected and availability of data collection tools) and an immunization service observation guide and checklist, (which comprised of several prompts to assess data management practices of immunization staff during vaccination sessions, and the data recorded in core data collection tools). These study tools were developed in English and French, and pre-tested in four facilities in the Centre region before being used to collect data for the study.

Data management and analysis

A comprehensive database was built, pre-tested and validated by an expert data manager prior to data entry. Each assessor entered data from the filled questionnaires and observation forms into the database and transmitted the files to a secure server within three days of data collection. Data were exported and cleaned in Microsoft Excel 2016 and analyzed with Stata 13 software (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.). Frequencies and proportions were used to summarize variables, with health facility used as the unit of analysis. Since districts and facilities were sampled proportional to national distributions, no post-stratification weights were applied.

Operational definitions

-

Data management practices: This included data collected, availability and utilization of data collection tools, data consistency across collection tools and data recording practices during vaccination sessions.

-

Vaccination staff (Used interchangeably with immunization staff, vaccine-providers, vaccinators): This included all health staff working in the immunization unit.

-

Completely filled data collection tool: All required columns of the immunization tool were filled, for one month until the time of assessmentTo examine this data on completeness for five routine immunization tools was assessed: Immunization register, tally sheets, monthly reporting form, temperature chart, stock ledger.

Administrative approval

Administrative approval was obtained from the ministry of public health and all ten regional delegations of public health prior to commencement of the baseline assessment.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and all applicable national laws and institutional rules ethical approval was granted by the Cameroon National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research prior to study commencement.

Results

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of surveyed facilities. Overall, 265 health facilities in 68 health districts were surveyed, with slightly over half (53%) of these facilities located in rural areas. At least two staff worked in the immunization service in most (74%) of these facilities. Over two-thirds (67%) had staff who have never received training on immunization (Table 1). We also noted great regional variations in trainings, with 93% and 100% surveyed in the South region and East regions lacking a single staff who has received basic training on immunization, respectively.

Data collected by health facilities

Table 2 summarizes the practices of healthcare workers with regards to documenting data on vaccine administration. As illustrated 92% of facilities systematically collect vaccine administration data (filling of tally sheets, immunization registers and vaccination cards) at national level. At regional level, marked variations were observed. As shown in Table 2, about a quarter of (24%) of surveyed facilities in the East and South-West Regions did not document vaccine administration data. Only 65% and 61% of health facilities collected stock levels and vaccine wastage respectively. As regards temperature monitoring, most (79%) facilities recorded vaccine storage temperatures at the time of assessment.

Availability and utilization of data collection tools

At national level, majority of health facilities had core vaccination data collection tools, including tally sheets (84%), registers (87%), reporting forms (85%). Conversely, only 43% of facilities had vaccination cards, 8% had maintenance registers and 32% had stock cards. Regarding the use of these tools, immunization registers were filled in only 63% of health facilities and tally sheets just in 19% of facilities. Similarly, only 13% of facilities had updated and fully filled monthly report forms. These findings are shown in Table 2.

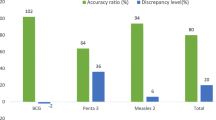

Data consistency across recording tools

Discrepancies for the same data was noted across three core data collection tools assessed (tally sheets, immunization registers and monthly reporting forms). The Pentavalent 3 value from the tally sheets and monthly reporting forms was different in over half (53%) of the health facilities. This was observed across all regions and the highest percentage of health facilities with inconsistent data across sources was noted in the South (85%) and Littoral (81%) regions, as shown in Table 2.

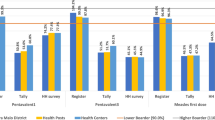

Data recording practices during immunization sessions

Immunization registers and tally sheets were present at the vaccination site in up to 90% of facilities. Similarly, in most (85%) health facilities, immunization acts were documented in registers, tally sheets and vaccination cards as recommended, with regional variations (ranging from 73% in the East region to 100% in the North-West and South-West regions). Conversely, only 11% of health facilities adhered to the recommendation of filling the tally sheet as children were vaccinated. Up to 51% of these facilities rather filled the sheets before vaccination, and 25% did so after vaccination as illustrated in Table 3.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to assess the data management practices of immunization staff at health facility level, in a bid to unveil potential barriers to vaccine data quality in Cameroon. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published study examining the data management practices of vaccination staff on a national scale in Cameroon. We noted several unsatisfactory data collection and management practices in a good proportion of facilities including ineffective use of data collection tools, filling tally sheets before or after vaccination, sub-optimal collection of data on some key immunization indicators. This study also found that the unavailability of core data recording tools was not uncommon and could contribute to substandard data collection and eventually immunization data quality.

We noted various gaps when it comes to recording immunization data at facility level. In our study we found that about one in every ten (8%) of facilities did not collect data on vaccine administration; about one in three (35%) did not collect data on stock levels and about two in five (21%) did not record vaccine storage temperatures and vaccine wastage. Our findings lend support to those documented in multiple settings [7, 9, 10, 27]. As documented elsewhere, several technical, organizational and behavioral factors may explain the root causes of the observed deficits in this study, including gaps in health provider capability and motivation, poor supportive supervision, unavailability or complexity of data recording tools, lack of performance-based targets, and interrupted regular feedback [12, 28]. Deficits in capacity and capability could explain the gaps in indicators like vaccine wastage, which may be relatively more complex to compute. The observed data collection gaps could also be linked to the limited availability of some data recording tools like vaccination cards, maintenance registers and stock cards, which were lacking in 57%, 92% and 43% of surveyed facilities, respectively (Table 2).

The availability of immunization registers (87%) and tally sheets (83%) in our study is higher than what was reported by Kefiyalew et al. (available in 43–50% of facilities) in Ethiopia [12] and Ronveaux et al. [11] in 27 GAVI-supported countries, including Cameroon (available in 60% of facilities). These differences could be because Kefiyalew’s study was carried out only in one health district while Ronveaux’s study assessed availability of tools over a one-year window, unlike ours which assessed only during the study period. Difference could also reflect improvements by Cameroon’s EPI, to ensure that these critical data collections are available at facility level. Such improvements were, to a large extent, driven by governments efforts to introduce new vaccines such as IPV, combined measles vaccines, HPV etc., which are always accompanied by updating and distribution of various data collections tools. Other organizations, such as the Clinton Health Access initiative and Unicef have also supported the government to provide facilities with registers.

We also found that even when data recording tools were available and used, they were ineffectively used and incompletely filled in a good proportion of facilities, further aggravating data quality problems at facility level. This finding is comparable to that of Wallace et al. (2017) in Nigeria, who reported that only 51–55% assessed facilities stock records with sufficient data to calculate vaccine wastage rates [29]. Additionally, our study noted inconsistencies for the same data recorded across different core data recording tools. For instance, the Pentavalent 3 value from the tally sheets and monthly reporting forms was discrepant in over half (53%) of the health facilities. This finding is slightly lower compared that reported by Akerele et al. (2020) in neighboring Nigeria, who showed that Pentavalent 3 values between the health facility monthly summary form and the national health management information systems monthly summary form were discrepant in 67% assessed facilities in Kano State [27]. These gaps can be corrected by health worker training on immunization data tools and regular supportive supervisory visits, interventions which have been shown by Akerele et al. (year) as important determinants of good data consistency.

In our study we also identified some data management practices during vaccination sessions which could contribute to incomplete, or inaccurate or inconsistent data. Just over a tenth (11%) of health facilities adhered to the recommendation of filling the tally sheet as children are being vaccinated, instead of filling them before or after vaccination. This could lead to either under-reporting or over-reporting of vaccinated children, resulting into poor data quality which could impact in-country and external investments, and frustrate efforts in reaching zero-dose children and under-immunized children. This further reemphasizes the need for staff capacity building, supportive supervision, and standardization of data recording processes.

While interpreting the findings of our study, some limitations have to be considered. Our study may be biased by the Hawthorne effect because EPI personnel were aware of being observed and may have modified their behaviors during the study period. Secondly, data management practices were assessed at health facility level, thus individual level variations at health facility level could be missed.

Conclusion

This study brings to light several unsatisfactory data management practices of vaccination staff in Cameroon, including ineffective use of data collection tools, filling tally sheets before or after vaccination, sub-optimal collection of data on some key immunization indicators. These, coupled with unavailability of key data recording tools, could hinder the generation of timely, high-quality data, and ultimately affect decision making and delivery of immunization services. There is thus a crucial need to standardize data recording processes, systematically build data management competencies of health facility EPI staff in Cameroon, while building policies and systems that ensure constant availability of data recording tools.

Data Availability

Data used for this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHAI:

-

Clinton Health Access Initiative

- EPI:

-

Expanded Program on Immunization

- HCW:

-

Healthcare workers

- HF:

-

Health facility

- MCV:

-

Measles containing vaccine

- MOV:

-

Missed Opportunities for Vaccination

- VPD:

-

Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

- WHO-MDVP:

-

WHO Multi-dose Vaccine Policy

References

World Health Organisation., Regional Office of Africa. Immunization [Internet]. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. [cited 2023 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/immunization.

Li X, Mukandavire C, Cucunubá ZM, Londono SE, Abbas K, Clapham HE, et al. Estimating the health impact of vaccination against ten pathogens in 98 low-income and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2030: a modelling study. The Lancet. 2021;397(10272):398–408.

Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Brenzel L, Walker DG. Return On Investment from Childhood Immunization in low- and Middle-Income Countries, 2011-20. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(2):199–207.

World Health Organisation. Immunization Agenda 2030: A global strategy to leave no one behind [Internet]. Geneva. ; 2020. Available from: (https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org.

Shen AK, Fields R, McQuestion M. The future of routine immunization in the developing world: challenges and opportunities. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(4):381–94.

Lindstrand A, Cherian T, Chang-Blanc D, Feikin D, O’Brien KL. The World of immunization: achievements, Challenges, and Strategic Vision for the Next Decade. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(Supplement4):452–67.

Wetherill O, Dietz V. Lee chung won. Annals of Infectious Disease and Epidemiology. 2017.

Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance. Data [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/types-support/health-system-and-immunisation-strengthening/data.

Harrison K, Rahimi N, Carolina Danovaro-Holliday M. Factors limiting data quality in the expanded programme on immunization in low and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Vaccine. 2020;38(30):4652–63.

Murray CJ, Shengelia B, Gupta N, Moussavi S, Tandon A, Thieren M. Validity of reported vaccination coverage in 45 countries. The Lancet. 2003;362(9389):1022–7.

Ronveaux O, Rickert D, Hadler S, Groom H, Lloyd J, Bchir A, et al. The immunization data quality audit: verifying the quality and consistency of immunization monitoring systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(7):503–10.

Kefiyalew B, Abay S, Mamo W, Abate B, Chanyalew MA, Ayalew Y et al. Assessment of immunization data management practices, facilitators, and barriers to immunization data quality in the health facilities of Tach Gayint district, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development [Internet]. 2021 Nov 25 [cited 2023 Jan 7];35(3). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/217887.

Programme Elargie de Vaccination(PEV)., Ministère de la Santé, Cameroon. PEV:: Historiques [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 1]. Available from: https://pevcameroon.cm/apropos/histories.

World Health Organisation. Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) immunization coverage among 1-year-olds, Global Health Observatory. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/diphtheria-tetanus-toxoid-and-pertussis-(dtp3)-immunization-coverage-among-1-year-olds-().

Programme Elargie de Vaccination(PEV), Ministère de la Santé, Cameroon. Plan Pluriannuel Complet 2015–2019 [Internet]. 2014. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/file-repository/CMR.

Russo G, Miglietta A, Pezzotti P, Biguioh RM, Bouting Mayaka G, Sobze MS, et al. Vaccine coverage and determinants of incomplete vaccination in children aged 12–23 months in Dschang, West Region, Cameroon: a cross-sectional survey during a polio outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):630.

Ateudjieu J, Kenfack B, Nkontchou BW, Demanou M. Program on immunization and cold chain monitoring: the status in eight health districts in Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):101.

Yakum MN, Ateudjieu J, Walter EA, Watcho P. Vaccine storage and cold chain monitoring in the North West region of Cameroon: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):145.

Yauba S, Sobngwi J, Jude N, Tracy B, Kobela M, Charles N et al. Temperature monitoring in the Vaccine Cold Chain in Cameroon. J Vaccines Vaccination. 2017;09.

Yauba S, Harmelle EE, Marius VZ, Jude N, Delphine K, Calvin T, et al. Availability and status of Vaccine Cold Chain Equipment in Cameroon. J Vaccines Vaccination. 2019;10(2):1–6.

Ebile Akoh W, Ateudjieu J, Nouetchognou JS, Yakum MN, Djouma Nembot F, Nafack Sonkeng S, et al. The expanded program on immunization service delivery in the Dschang health district, west region of Cameroon: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):801.

World Bank Group. Population, total - Cameroon | Data [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 3]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CM.

Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon. Cameroon [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.prc.cm/en/cameroon.

World Health Organization. Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): case study from Cameroon, abridged version. Geneva; 2017.

Ministry of Public. Health, Cameroon. Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027.

EPI-Ministry of Public Health. Digitalization of the Health Information System: current situation and prospects. BLN discussion meeting; 2017.

Akerele A, Obansa R, Adegoke OJ, Haladu S, Adeoye OB, Usifoh N et al. Determinants of improved data consistency across routine immunization data tools for health facilities in Kano State, Nigeria. The Pan African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2020 Jul 2 [cited 2023 Jan 10];36(148). Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/36/148/full.

Scobie HM, Edelstein M, Nicol E, Morice A, Rahimi N, MacDonald NE, et al. Improving the quality and use of immunization and surveillance data: Summary report of the Working Group of the Strategic Advisory Group of experts on immunization. Vaccine. 2020;38(46):7183.

Wallace AS, Willis F, Nwaze E, Dieng B, Sipilanyambe N, Daniels D, et al. Vaccine wastage in Nigeria: an assessment of wastage rates and related vaccinator knowledge, attitudes and practices. Vaccine. 2017;35(48 Pt B):6751–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors will like to acknowledge the Regional delegates and districts staff for facilitating the conduct of the study in their respective districts and regions and the facility staff for their collaboration.

Funding

This study was funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), however the outcome of the study does not necessarily represent the views of BMGF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception & Design: YS, JG, AAN, NJM, VMZ, Statistical analysis: VNA, NJM, Initial draft preparation: YS, SCN, BMN, CMM, Review and Editing: YS, NEN, NJM, VMZ, CMM, VNA, DO, AAN, JF, DD, OW, EM, SACC, Supervision: YS, OW, JG, SACC, EM, RC. All Authors read and approved the submission of the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and all applicable national laws and institutional rules and approved by Clinton Health Access Initiative Scientific and Ethical Review Committee (SERC). Ethical approval was granted by the Cameroon National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Administrative Approval

Administrative approval was obtained from the ministry of public health before data collection. Additionally, written approvals were also obtained from all regional delegations of public health, who in turn issued administrative letters to district heads requesting full support for the data collection process.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Saidu, Y., Gu, J., Ngenge, B.M. et al. Assessment of immunization data management practices in Cameroon: unveiling potential barriers to immunization data quality. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 1033 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09965-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09965-9