Abstract

Background

Low birth weight (LBW) is an important factor influencing infant morbidity and mortality. Pregnant women should receive a variety of interventions during antenatal care (ANC) that are crucial in improving birth weight. ANC visits alone do not promise that women have received all recommended antenatal services. However, there are limited evidence of the relationship between ANC quality and LBW in Rwanda. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the association between quality ANC and LBW along with the factors influencing LBW and how quality ANC affects LBW in Rwandan pregnant women.

Methods

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are cross-sectional, nationally representative household surveys that collect population, health, and nutrition. In this Study we used three waves of Rwanda Demographic and Health Surveys 2010,2014-5 and 2019-20. A total of 16,144 women aged 15 to 49 years who had live births in the five years preceding each survey were included in this study. A stratified two-stage sampling methods was used to select the participants. The first stage involves selecting clusters (villages) from a list of all clusters in the country. The second stage involves selecting households within each cluster. A survey adjusted for clusters at multiple level and a bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios(aOR) and 95% confidence intervals to assess the association between the outcome and independent variables.

Results

The utilization of a high-quality ANC increased slightly over the three survey years and LBW had a slow decline. Out of 5813 women;201(3.45%) had high-quality ANC in the 2010 survey, and out of 5813 newborns,180(3.10%) were LBW. Out of 5404 women;492(9.11%) had high-quality ANC in 2015, and out of 5404 newborns,151(2.79% were LBW). Out of 5203 women,776(14.92%) had high-quality ANC in the 2020 survey year, and out of the 5206 newborns,139(2.67%) were LBW. In multivariable analysis, at a borderline limit high quality ANC was negatively associated with LBW(aOR:0.67;95%CI:0.43,1.05) compared to low-quality ANC. Higher birth orders of the newborn were negatively associated with LBW (aOR:0.63;95%CI:0.49,0.82 and aOR:0.44;95%CI:0.32,0.61 for 2nd -3rd and 4th and above respectively) compared to 1st orders newborn. Newborns from rich households were less likely to experience LBW than those from poor households (aOR:0.71;95%CI:0.55,0.91). Female newborns were associated with an increase of LBW (aOR:1.43;95% CI:1.18,1.73) than male newborns.

Conclusion

The findings confirm the fundamental importance of a high-quality ANC on LBW. The findings could be utilized to develop monitoring strategies and assess pregnancy health assistance programs with a focus on LBW reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), low birth weight (LBW) is defined as an infant’s birth weight of less than 2500 g, regardless of gestational age or other factors [1]. LBW causes 60–80% of all newborn deaths worldwide and increases the risk of mortality by 20–30 times [2, 3]. Immediately following delivery and for the first year of life, surviving newborns are more susceptible to pathological diseases like infection [4]. Later-life morbidity is also linked to LBW, including psychosocial disorders [5], poor cognitive function [6], coronary heart disease [7], and non-insulin-dependent diabetes [8].

Low and middle-income countries(LMICs) and especially Sub-Saharan Africa(SSA) countries are affected by a higher rate of LBW, WHO estimates that roughly 95.6% of the more than 20 million LBW babies (representing 15.5% of all live births) are in LMICs [9], estimated LBW levels in SSA are at 15% [10, 11]. This is related to the inadequate health infrastructure and permeable social support systems found in the majority of developing nations, which have a detrimental effect on health outcomes. Several studies on LBW in SSA have demonstrated that adherence to antenatal care (ANC) services, maternal body mass index(BMI), the receipt of iron and folic acid during pregnancy, gender of the newborn, demographic and socioeconomic factors such as household wealth index, maternal age, and maternal education were associated to LBW of the newborn [12,13,14,15].In addition, the risk of LBW has been linked to both maternal malnutrition and malaria infection [16]. During the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, intermittent preventative therapy (IPT) for malaria is administered in places where the disease is endemic [17, 18]. Malaria-related birth outcomes can be worsened by inadequate prenatal care attendance, which can also reduce the amount of IPT doses provided [18].

The aforementioned ANC package components have been demonstrated to be cost-effective in reducing the prevalence of LBW elsewhere in SSA [19, 20]. The majority of research on the relationship between ANC and birth weight has been done in high-income countries, even though the prevalence of LBW is higher in low and middle-income countries [21].

The Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (RDHS) report indicates a prevalence of LBW of 7% [22]. Rwanda’s neonatal mortality rate is estimated to be 18 per 1000 live births, far higher than the United Nations(UN) Sustainable Development Goal 3.2(SDG), which is to reduce neonatal mortality to less than 12 per 1000 live births [23, 24].LBW has been significantly associated with neonatal mortality in resource-limited settings [25, 26]. A study conducted in Rwanda found that 70% of perinatal deaths included low birth weight newborns [27]. For Rwanda to achieve the SDGs in neonatal mortality, determinants of LBW should be assessed to inform the policymakers in the health sector. The 2016 WHO guidelines on ANC recommend at least 8 contacts for every pregnant woman; however, Rwanda still implements the 2001 policy which only recommended 4 visits [22]. According to studies, the quality and content of ANC rather than the number of visits has a stronger influence on maternal and newborn health [28,29,30,31]. Quality ANC is when a woman had her first ANC visit within 3months of pregnancy, had 4 or more ANC visits as recommended by WHO [32], and received services components of ANC during the visits(found to be crucial for quality pregnancy care by WHO) [33] by a skilled provider [34]. The choice of this model was adapted from Bollini and colleagues who proposed indicators to help measure quality ANC [35] and referred to a cross-sectional study conducted in India in 2019 [36]. To improve neonatal outcomes in Rwanda, it is imperative to examine the quality and uptake of ANC and their association with LBW.

Few studies have been conducted at the Rwanda country level to examine the associations between quality ANC, health and socioeconomic factors, and LBW [14]. We sought to breach this gap by exploring the associations between quality ANC and potential confounders on LBW.

Methods

Study design and data source

This study is a cross-sectional study using secondary data from three waves of the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (RDHS). The three waves include RDHS 2010, RDHS 2015, and RDHS 2020. The RDHS is a cross-sectional survey that gathers a sample of households that is nationally representative using a two-stage sampling design. For women in all three waves, response rates were high, topping 99%. The RDHS gathers information on mother and child health during a time frame within the five years prior to the survey. Information on the sample design, sample size, study tools, data collection, getting informed consent, and other related methodologies is presented elsewhere [22]. The datasets of RDHS data were accessible from the Measure DHS website at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Analytic sample

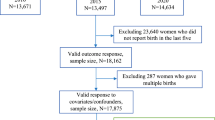

For the purpose of this study, the 2010, 2015, and 2020 RDHS birth recode (BR) datasets were merged based on established guidelines for managing DHS data. Women aged 15 to 49 years old who had a single live birth in the five years prior to each survey and had at least one antenatal care visit answered questions about antenatal care visits(ANC) were included in this sample. Women with missing data or invalid responses to the key exposure, outcome, and possible confounders, such as “don’t know”, were removed. 16,144 of the 41,802 women who took part in the survey met the requirements for inclusion. the flow chart and the analytic sample selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Out of 16,144 births included in this study, information on birth weight was available for 15,560 (96.4%) newborns. Birth weight was obtained through health cards for 4824 (31%) and through maternal recall for 10,736 (69%) newborns.

Study variables

Outcome and exposure

The main outcome was LBW, classified as < 2500 g birth weight. The main exposure variable was quality ANC. Quality ANC is a dichotomous variable, high-quality ANC and low-quality ANC. High-quality ANC is a composite variable which was defined as having had the first ANC visit in the first trimester of pregnancy, had > = 4 ANC visits, having ANC provided by skilled personnel such as a medical doctor, nurse, or midwife and having received all the five interventions during the pregnancy. The five interventions that mark quality ANC are the test of the blood pressure, a urine sample taken, a blood sample taken, giving or bought iron tablets, and receiving a tetanus injection. Low-quality ANC is when the woman missed any quality indicator of ANC.

The definition of the variable “high-quality ANC” was adapted from Bollini P. and colleagues who suggested indicators to assist quantify the quality of antenatal care [35] and referring to a recent study in India [36].

Community level, socioeconomic and demographic factors but also individual level and health service factors were considered as explanatory variables for their relevance in the uptake of ANC and impact on LBW. These factors were adapted from Andersen’s behavioral model, Mosley and Chen [37]. Many studies have made use of Andersen’s behavioral model and the analytical framework by Mosley and Chen to study the determinants of maternal health services utilization and birth outcomes [37,38,39]. These factors were: Age, type of place of residence (urban, rural), water sources, marital status, preceding birth interval, sex of newborn, maternal education level, household’s wealth index, access to media, birth order, maternal BMI, type of cooking fuel, iron supplementation, receipt of antimalarial treatment. Numerical values like age, birth order and maternal were grouped into categories. Maternal age in years was tabulated into groups (15–19 years, 20–34 years, 35–49 years); the birth order of the baby was into three categories (1st ,2nd -3rd ,4th and above). The preceding birth interval was grouped into two categories (< 24months and > = 24months). utilizing principal component analysis, the household wealth index was created utilizing data on the ownership of durable assets, access to utilities and infrastructure, and dwelling features. 20% of the population of women were divided into five categories depending on their household asset score: poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest. Later, three categories (poor, middle class, and rich) were created using these five criteria.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were conducted using Stata v17.0 [40]. Descriptive statistics for the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants were generated using the frequency and percentage as shown in Table 1. We used chi-square tests to identify demographic and socio-economic factors associated with the outcome variable. Crude odds ratios were generated using bivariate analyses to determine the odds of each outcome variable with explanatory variables using logistic regression models. Potential factors with p < 0.20 were retained for multivariable analysis. When covariates were found to be collinear, using the variance inflation factor(VIF > 4), the variable that was most correlated with the outcome variable of interest was retained. To account for clustering, stratification, and sample weight, we ran all analyses using the survey module “svyset” stata commands.

Results

Table 1 presents a description of 16,423 mothers of newborns. More than half of the study participants were young women (66.83%) 20–34 years of age. The majority of the study participants resided in rural areas (84.85%), nearly a quarter (70.29%) of the respondents had a primary education level and most (81.69%) were married. In addition, 44.12% of the respondents were in the poor tercile,61.53% of them accessed the media at least once a week and the majority (84.75%) used solid fuel for cooking. Additionally, most of the respondents spaced the birth by 2 years and above (88.14%).

Quality ANC and LBW

Nearly a tenth (8.94%) of respondents presented high-quality antenatal care, and 2.82% of newborns were born with LBW.

Table 2 shows the details of the interrelationship between various determinants of quality ANC and LBW. Female newborns had 43% increased odds of LBW (aOR:1.43;95% CI:1.18,1.73) compared to male newborns. Rich mothers had 29% decreased odds of LBW(aOR:0.71;95%CI:0.55,0.91) compared to the poor mothers and an increase in the birth order of the newborn reduced the odds of LBW (37% reduced odds for 2nd -3rd birth order aOR:0.63;95%CI:0.49,0.82 and 56% reduced odds for 4th and above birth order aOR:0.44;95%CI:0.32,0.61) compared to the 1st order newborns. High-quality ANC reduced by 33% the odds of LBW(aOR:0.67;95%CI:0.43,1.05) compared to low-quality ANC.

Figure 2 shows a trend in the percentage of high-quality ANC and LBW. High-quality ANC increased over the last 15 years, and the prevalence of low birth weight decreased.

Discussion

The current study investigated the association between quality ANC and LBW. We found that 8.94% of the mothers had high-quality ANC visits and 2.82% of the newborns were low birth weight; this result shows that high-quality antenatal care enabled a reduction by 4.18% of the low birth weight to the national average which stands for at 7% according to the report of the most recent survey [22].

Our study showed that high-quality ANC visits was a predictor of LBW. When compared to low-quality ANC visits, high-quality ANC visits had a lower risk of LBW. A recent hospital-based study in Rwanda discovered that women who received four or more ANC visits had a decreased incidence of LBW [41]. Several studies have shown similar conclusions [42,43,44,45]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least four antenatal checkups throughout pregnancy since this is a time when babies are vulnerable to issues such as preterm birth, restricted fetal growth, and congenital infections, all of which increase the likelihood of neonatal death [46]. In addition, attending ANC has been suggested as a possible avenue for mothers and their families to receive information and advice on obstetric care as well as the identification and management of infections such as Malaria, HIV/AIDS, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted diseases that affect the fetus [46]. This emphasizes the necessity of implementing population-based interventions that promote early ANC attendance [44].

Other predictors of LBW include the female gender of newborn. Female neonates were more likely than male neonates to have low birth weight. Findings in Ghana, India, and Brazil corroborate our findings [47,48,49]. According to Volder and colleagues’ research, paternal birth weight has a considerable impact on boys’ birth weight, but not on girls’ birth weight [50]. LBW was also found to be negatively linked with the rich tercile. Low birth weight neonates were less likely to be delivered by mothers in the rich tercile than by mothers in the poor tercile. Previous research has found that having a higher socioeconomic status lowers the risk of LBW [51,52,53,54]. Low birth weight has been linked to poor prenatal nutrition among mothers of lower socioeconomic classes, according to studies [55, 56]. The likelihood of LBW decreases as the newborn’s birth order rises. Several studies have come to the same conclusion [43, 44, 57]. A recent longitudinal study in Germany discovered an increase in birth weight with the newborn’s birth order, implying that the biological intrauterine component is likely to alter mother physiology in favor of later borns and recommending additional research into sibling pregnancies [58].

Our findings demonstrate that a small percentage of women received a high-quality ANC and that their number increased throughout the three waves of surveys. The increase in high-quality ANC played a key role in reducing the prevalence of LBW. However, the prevalence of LBW is still high, future research would examine the effect of several mediator variables such as maternal nutrition during pregnancy on LBW to effectively address this adverse neonatal outcome.

Strengths and limitations

The study’s use of a nationally representative population-based, combined dataset is a notable strength. We were able to generate a large sample size by merging the three surveys, which allowed us to assess the impact of various factors on LBW with acceptable precision. Because the three DHS used similar sample procedures and questionnaires, used comparable data collection tools, and were planned and implemented by the same institutions, they allowed researchers to look into trends in low birth weight over the past 15 years. This study provided evidence-based information for the decision-makers which can help in the implementation of public health policies regarding ANC improvement and evaluations. Data on key major determinants of maternal healthcare consumption, such as health insurance, was only gathered for the most recent survey, which limited our ability to assess the impact of such variables. Not all potential confounders were included in our study; for instance, gestational age, could have reduced the quality of the results. Variables such as facility readiness, interpersonal relationships between clinicians and women, transportation, and other cultural norms and beliefs that could have influenced a high-quality ANC utilization were not included in this study. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we were only able to investigate relationships rather than causality. Further researchers would conduct a longitudinal study design to assess the causality between ANC and LBW.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that the use of high-quality ANC has gradually increased. However, the vast majority of the women are still receiving low-quality ANC. The prevalence of LBW has decreased over the years of the surveys, however, it remains high. Addressing the coverage but also the quality of the content in ANC, especially to the poor and primiparous women results in the reduction of the prevalence of LBW. The study revealed that the utilization of high-quality ANC can greatly contribute to lessening LBW and thus neonatal mortality and therefore achieving the SDGs.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the DHS program website http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm but registration and application is required before access to data is granted.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- RDHS:

-

Rwanda demographic and Health Survey

- LBW:

-

Low Birth Weight

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- IPT:

-

Intermittent Preventative Therapy

References

Tafere T, Afework MFYA. Providers adherence to essential contents of antenatal care services increases birth weight in Bahir Dar City Administration,north west Ethiopia: a prospective follow up study. Reprod Health. 2018;15:163.

Romero CX, Duke JK, Dabelea D, Romero TEOL. Does the epidemiologic paradox hold in the presence of risk factors for low birth weight infants among Mexican-born women in Colorado? J Heal Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):604–14.

Lawn J, Blencowe H, Oza S, You D, Lee AC, Waiswa P, et al. Every newborn:progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet. 2014;12(9938):189–205.

Varga P, Berecz B, Gasparics A, et al. Morbidity and mortality trends in very-very low birth weight premature infants in light of recent changes in obstetric care. Eur J Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;211:134–9.

Nomura Y, Wickramaatne PJ, Pilowsky DJ, Newcorn JH, Bruder-Costello B, Davey C, et al. Low birth weight and risk of affective disorders & selected medical illness in offspring at high and low risk for depression. Compr Psych. 2007;48(5):470.

Farajdokht F, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Dehghani R, Mohaddes G, Abedi L, Bughchechi R, et al. Very low birth weight is associated with brain structure abnormalities and cognitive function impairments: a systematic review. Brain Cogn. 2017;118:80–9.

Wang SF, Shu L, Sheng J, Mu M, Wang S, Tao XY, et al. Birth weight and risk of coronary heart disease in adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Dev Orig Heal Dis. 2014;5(6):408–19.

Ova J, Nakagami T,Kurita M, Yamamoto Y,Hasegawa Y,Tanaka Y et al. Association of birth weight with diabetes and insulin sensitivity or secretion in the japanese general population. J Diabetes Investig 6:430–5.

Metgud C, Naik V, Mallapur M. Factors affecting Birth Weight of a newborn – A community based study in rural Karnataka, India. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40040.

Blencowe H, Krasevec J, Onis MD, Black R, An X, Stevens G, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2019;7(7):e849–60.

Barros FC, Barros AJ, Villar J, Matijasevich A, Domingues MRVC. How many low birthweight babies in low- and middle-income countries are preterm? Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(3):607–16.

Tessema ZT, Tamirat KS, Teshale AB, Tesema GA. Prevalence of low birth weight and its associated factor at birth in Sub-Saharan Africa: a generalized linear mixed model. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0248417. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248417.

He Z, Bishwajit G, Yaya S, Cheng Z, Zou D, Zhou Y. Prevalence of low birth weight and its association with maternal body weight status in selected countries in Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020410. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020410.

Biracyaza E, Habimana MS, Rusengamihigo D, Evans H. Regular antenatal care visits were associated with low risk of low birth weight among newborns in Rwanda: Evidence from the 2014/2015 Rwanda Demographic Health Survey (RDHS) Data. F1000Research. 2022;10:402.

Weyori A, Seidu A-A, Aboagye R, Arthur-Holmes F, Okyere J, Ahinkorah B. Antenatal care attendance and low birth weight of institutional births in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:283.

Cates JE, Unger HW, Briand V, Fievet N, Valea I, Tinto H, et al. Malaria, malnutrition, and birth weight: A meta-analysis using individual participant data. PLos Med. 8 14(8):e1002373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002373.

Schallig HDFH, Scott S, Traore-Coulibaly M, et al. Evaluation of malaria screening during pregnancy with rapid diagnostic tests performed by community health workers in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:1190–7.

Grietens KP, Gies S, Coulibaly SO,Ky C,Somda J, Toomer E, Muela Ribera JDU. Bottlenecks for high coverage of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy: the case of adolescent pregnancies in rural Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE 5:e12013.

Adam T, Lim S, Mehta S, Bhutta ZA, Fogstad H, Mathai M, Zupan JDG. Achieving the millenium development goals for health-cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. Br Med J. 2005;331(7525):1107–10.

Lambon-Quayefio MPON. Examining the influence of antenatal care visits and skilled delivery on neonatal deaths in Ghana. Appl Heal Econ Heal Policy. 2014;12(5):511–22.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on optimal feeding of low birth weight infants in low- and middle-income countries. WHO. 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85670. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda(NISR). M of H (MOH)[Rwanda] and I. Rwanda demographic and Health Survey 2019-20 final report. Kigali,Rwanda and Rockville,Maryland,USA; 2021.

UNICEF,WHO,World Bank UD. mortality rate,neonatal. world bank group. 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.NMRT?locations=RW. Accessed 2 Feb 2022.

World Health Organization. World health statistics 2020:monitoring health for the SDGs,sustainable development goals. Geneva,Switzerland; 2020.

Arunda MO, Agardh A, Asamoah BO. Survival of low birthweight neonates in Uganda: analysis of progress between 1995 and 2011. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1831-0.

Nahimana E, Ngendahayo M, Magge H. Amoroso CL,Muhirwa E,Uwilingiyemungu JN,Nkikabahizi F,Habimana R H-GB. Bubble CPAP to support preterm infants in rural Rwanda:a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 24:135.

Musafili A, Persson L-Ã, Baribwira C, Påfs J, Mulindwa PA, Essén B. Case review of perinatal deaths at hospitals in Kigali, Rwanda: perinatal audit with application of a three-delays analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1269-9.

Arsenault C, Jordan K, Lee D, Dinsa G, Manzi F, Marchant T, et al. Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 national household surveys. Lancet Glob Heal. 2018;6:e1186–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30389-9.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran A, Campbell O. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3:e000779.

Manzi A, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, Magge H, Bigirimana E, Mukanzabikeshimana L, et al. Beyond coverage: Improving the quality of antenatal care delivery through integrated mentorship and quality improvement at health centers in rural Rwanda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):136.

Hodgins SDA. The quality-coverage gap in antenatal care: toward better measurement of effective coverage. Glob Heal Sci Pr. 2014;2(2):173–81.

WHO. Antenatal care Randomized Trial:Manual for the implementation of the New Model. 2002. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42513/WHO_RHR_01.30.pdf. Accessed 21 Sep 2020.

World Health Organization. Pregnancy,childbirth,postpartum and newborn care:a guide for essential practice. 2nd edition. Geneva,Switzerland; 2006.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Bollini PQ-LK. Guidelines-based indicators to measure quality of antenatal care. J Eval Clin Pr. 2013;19:1060–6.

Singh L, Dubey R, Goel R,Nair SSP. Measuring quality of antenatal care:a secondary analysis of national survey data from India. BJOG. 2019;4:7–13.

Babitsch B, Gohl DLT. Re-visiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use:a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9.

Beeckman K, Louckx F, Putman K. Determinants of the number of antenatal visits in a metropolitan region. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:1–9.

Guliani H, Sepehri A, Serieux J. Determinants of prenatal care use: evidence from 32 low-income countries across Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:589–602.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. 2021.

Akintije CS, Yorifuji T, Wada T, Mukakarake MG,Mutesa LYT. Antenatal Care visits and adverse pregnancy outcomes at a hospital in Rural Western Province,Rwanda. Acta Med Okayama. 2020;74:495–503.

Kassar SB, Melo AM, Coutinho SB, Lima MCLP. Determinants of neonatal death with emphasis on health care during pregnancy,childbirth and reproductive history. J Pediatr(Rio J). 2013;89:269–77.

Khatun SRM. Socio-economic determinants of low birth weight in Bangladesh: a multivariate approach. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2008;34:81–6.

Allemseged A, Mektie WSB. Maternal risk factors associated with low birth weight. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13:25–8.

Kananura RM, Wamala R, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Tetui M, Kiwanuka SN, Waiswa P, et al. A structural equation analysis on the relationship between maternal health services utilization and newborn health outcomes: a cross-sectional study in Eastern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1289-5.

Lincetto O, Mothebesoane-anoh S, Gomez PMS. Antenatal Care:Opportunities for Africa’s newborns. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2013;2:51–62.

Mondal B. Low birth weight in relation to sex of baby,maternal age and parity:a hospital based study on Tangsa tribe from Arunachal Pradesh. J indian Med Assoc. 1998;96:362–4.

Falcão IR, Ribeiro-Silva R, de Almeida C, Fiaccone MF, Rocha RL, Ortelan A et al. N,. Factors associated with low birth weight at term: a population-based linkage study of the 100 million Brazilian cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03226-x.

Agorinya IA, Kanmiki EW, Nonterah EA, Tediosi F, Akazili J, Welaga P, Azongo DOA. Socio-demographic determinants of low birth weight: Evidence from the Kassena-Nankana districts of the Upper East Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11).

Voldner N, Frøslie KF, Godang K, Bollerslev JHT. Determinants of birth weight in boys and girls. HUM Ontog. 2009;3:7–12.

Manyeh AK, Kukula V, Odonkor G, Ekey RA, Adjei A, Narh-Bana S, et al. Socioeconomic and demographic determinants of birth weight in southern rural Ghana: evidence from Dodowa Health and demographic Surveillance System. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0956-2.

Schulpis K, Karakonstantakis T, Vlachos G, Gavrili S, Mentis A-FA, Lazaropoulou C et al. The effect of nutritional habits on maternal–neonatal zinc and magnesium levels in Greeks and Albanians. E Spen Eur E J Clin Nutr Metab. 2009;4.

Dowding VM. New assessment of the effect of birth order and socioeconomic class on birth weight. Br Med J. 1981;282:683–6.

Fosu MO, Munyakazi L N-NN. Low birth weight and associated maternal factors in Ghana. J Biol Agric Healthc. 2013;3:7.

Shrivastava RSSP. A longitudinal study of maternal and socioeconomic factors influencing neonatal birth weight in pregnant women attending an urban health centre. Saudi J Heal Sci. 2013;2:87–92.

Fosu MO, Abdul-Rahaman IYR. Maternal risk factors for low birth weight in a District Hospital in Ashanti Region of Ghana. Res Obs Gynaecol. 2013;2:48–54.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics(UBOS) and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala,Uganda; 2012.

Bohn C, Vogel M, Poulain T, Spielau U, Hilbert C, Kiess W et al. Birth weight increases with birth order despite decreasing maternal pregnancy weight gain. Acta Paediatr. 2020;110. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15598.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received a grant from Shaanxi Open Sharing Platform of Critical Disease Prevention and Big Health Data Science(Grant No.2023-CX-PT-47).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.U Conceptualized the study idea, contributed to the study methodology and performed data analysis. M.E Contributed to the data analysis M.A.G Wrote original draft and contributed to the study design M. M.A Contributed to the study methodology. N.L: Contributed in data cleaning L Z: Provided mentorship and supervision. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a secondary analysis of the 2010,2014-15 and 2019-20 RDHS data; approval to access and download data files from the online DHS archive was granted by the worldwide DHS program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Uwimana, G., Elhoumed, M., Gebremedhin, M.A. et al. Association between quality antenatal care and low birth weight in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study design using the Rwanda demographic and health surveys data. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 558 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09482-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09482-9