Abstract

Background

Implementation of Professional Pharmacy Services (PPSs) requires a demonstration of the service’s impact (efficacy) and its effectiveness. Several systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCT) have shown the efficacy of PPSs in patient’s outcomes in community pharmacy. There is, however, a need to determine the level of evidence on the effectiveness of PPSs in daily practice by means of pragmatic trials.

To identify and analyse pragmatic RCTs that measure the effectiveness of PPSs in clinical, economic and humanistic outcomes in the community pharmacy setting.

Methods

A systematic search was undertaken in MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and SCIELO. The search was performed on January 31, 2020. Papers were assessed against the following inclusion criteria (1) The intervention could be defined as a PPS; (2) Undertaken in a community pharmacy setting; (3) Was an original paper; (4) Reported quantitative measures of at least one health outcome indicator (ECHO model); (5) The design was considered as a pragmatic RCT, that is, it fulfilled 3 predefined attributes. External validity was analyzed with PRECIS- 2 tool.

Results

The search strategy retrieved 1,587 papers. A total of 12 pragmatic RCTs assessing 5 different types of PPSs were included. Nine out of the 12 papers showed positive statistically significant differences in one or more of the primary outcomes (clinical, economic or humanistic) that could be associated with the following PPS: Smoking cessation, Dispensing/Adherence service, Independent prescribing and MTM. No paper reported on cost-effectiveness outcomes.

Conclusions

There is limited available evidence on the effectiveness of community-based PPS. Pragmatic RCTs to evaluate clinical, humanistic and economic outcomes of PPS are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The pharmacy profession is constantly evolving from the traditional role of dispensing medicines towards patient-centred and collaborative care [1, 2], as it adapts to the demands and needs of patients [3, 4]. This practice change [5], internationally acknowledged and supported by professional organisations [6, 7], involves expanding the roles of pharmacists, by increasing their responsibility for the outcomes of medication therapy [8]. In community pharmacy, the change is operationalized through the implementation of professional pharmacy services (PPSs). A professional pharmacy service is defined as “an action or set of actions undertaken in or organised by a pharmacy, delivered by a pharmacist or other health practitioner, who applies their specialized health knowledge personally or via an intermediary, with a patient/client, population or other health professional, to optimise the process of care, with the aim to improve health outcomes and the value of health care [9].”

In many countries PPSs are not integrated into daily practice due to a variety of factors. The main barriers are lack of evidence, lack of government support and/or no remuneration for service provision. However, the implementation process in various countries is at different phases and has followed different paths [10,11,12]. In some countries [12, 13] such as Australia, the United States of America (USA), Canada and the United Kingdom (UK), community pharmacists obtain reimbursement for providing these patient oriented services [2]. Most services are reimbursed by governments using a fee for service approach [14,15,16,17]. Implementation of reimbursed PPS normally requires a previous demonstration of the service’s impact (efficacy) and its effectiveness by means of high-quality research. However, translating these research findings into practice has been challenging [18, 19]. It is widely accepted that randomised control trials (RCTs) of various types are the appropriate research design to evaluate the efficacy of services while effectiveness should be assessed by means of pragmatic or naturalistic trials [20]. Generally, explanatory RCTs tend to maximize the accuracy of the results (internal validity) at the expense of external validity (the ability for a result to be applied or used in a particular situation) [21]. The term pragmatic is used for trials that test the effectiveness of the intervention in many clinical practice settings (e.g., inpatient hospitals, emergency departments) [11, 22,23,24] maximizing applicability and generalisability [25,26,27] (high external validity) of their results. Observational designs are also used to assess effectiveness [28, 29].

Several RCTs and systematic reviews have reported the clinical, economic and humanistic outcomes of PPSs in community pharmacy [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], although further research may be needed to determine whether these services can improve health-related quality of life and reduce healthcare costs [42]. Most of the studies reported in the literature have used an explanatory RCT design, which result in low external validity with consequent limitations associated with the generalisation of results [43,44,45,46]. Results from pragmatic trials may better meet the needs of stakeholders, healthcare professionals, payers [47,48,49] and patients [21]. As a result, there has been numerous calls to generate a high level of evidence on the clinical, economic and humanistic effectiveness of PPSs in daily practice by means of pragmatic trials [50,51,52,53]. It is, however, not easy, to differentiate between an explanatory and a pragmatic trial. Most trials seem to include both aspects, acknowledging the notion that explanatory and pragmatic exist in a continuum [54,55,56,57]. The PRECIS-2 tool was developed and validated to allocate research designs into this continuum. This tool consists of 9 domains scored from 1 (very explanatory) to 5 (very pragmatic). The domains are: eligibility, recruitment, setting, organisation, flexibility (delivery), flexibility (adherence), follow-up, primary outcome, and primary analysis. The main limitation of the PRECIS- 2 tool is that there may be interrater differences when applying each criterion. However, it provides explicit criteria that enhances discussion and eventual consensus [58, 59].The PRECIS-2 tool has shown a modest discriminatory validity [60].

This study aims to systematically review the literature to identify and analyse randomised controlled pragmatic trials that measure the effectiveness of the PPSs in the community pharmacy setting.

Methods

A systematic search was undertaken in MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and SCIELO, following PRISMA guidelines [61].

Search strategy

For the search performed in MEDLINE/PubMed the following Mesh terms and key words were used:“Outcome Assessment (Health Care)”[Mesh] OR (pragmatic[All Fields] OR (naturalistic[All Fields])))) OR (“Comparative Effectiveness Research”[Mesh] OR “Pragmatic Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Pragmatic Clinical Trial” [Publication Type]))) AND (“pharmaceutical care”[tiab] OR “medication review”[tiab] OR “Community Pharmacy Services”[Mesh] OR “Drug Utilization Review”[Mesh] OR “Medication Therapy Management”[Mesh] OR “clinical pharmacy service”[All Fields] OR “pharmacists”[MeSH Terms]). Filters: published in the last 10 years. The search strategies used in the other databases are included in Appendix. The search was performed by three of the authors (MAG, LSB and RVD) and the last update was made on January 31, 2020.

Selection criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for the selection process of papers: (1) The intervention assessed could be defined as a PPS according to Moullin’s definition [9]; (2) The intervention assessed was performed in the community pharmacy setting; (3) Was an original paper; (4) The trial reported quantitative measures of at least one health outcome indicator (ECHO model) [62]; (5) The study design was considered as a pragmatic RCT, that is, it fulfilled 3 of the 4 following key attributes [63, 64]: (a) analyzed the effectiveness of an intervention, (b) included more than 200 patients in each arm, (c) was undertaken in routine health care, (d) used broad eligibility criteria. Only articles in English and Spanish languages were included.

Data collection and analysis

Duplicated records were removed using Endnote©. The selection process was undertaken by the same three authors (MAG, LSB and RVD). Two independent researchers (RVD, MAG) reviewed the literature; and disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer (LSB). In addition, a manual search was performed for references not identified in the search through the references list of the retrieved papers. Abstracts were screened and excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Abstracts with insufficient information were assessed in full text. After excluding at the abstract level, the complete text of the remaining references was assessed against the same selection criteria.

The data-extraction form, after being piloted with a sample of three papers, included:

-

a)

Degree of pragmatism of the studies. To further characterize the degree of pragmatism of the finally included papers, the PRECIS-2 tool was used [65]. Three authors (MAG, LSB and RVD) rated the degree of pragmatism, scoring independently each trial/study on each of the 9 domains of the PRECIS-2. After the independent assessment there were minor differences which were resolved through a moderation-consensus approach.

-

b)

Internal validity was analyzed following the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. The following methodological aspects were selected to assess quality of the papers for this review; measure of variability, baseline comparability, contamination risk and blinded assessment [59].

-

c)

External validity was analyzed with the PRECIS- 2 tool [65].

-

d)

Description of general characteristics of included papers: type of PPS (interventions were categorized according to a hierarchical model [66], author, country, publication year, number of patients, duration, objectives, design/ method, patient inclusion/exclusion criteria and outcomes indicators).

-

e)

Description of the PPS components and summary of the clinical, economic or humanistic outcomes.

Trial registration: PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018073286 Available from:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=73286

Results

Search description

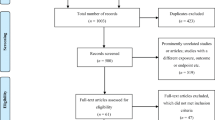

The search strategy retrieved 1556 papers and 31 additional papers were identified from the manual search from references of the included papers. After removing duplicates, a total of 1563 references remained. During the screening of abstracts, 1468 articles were excluded. Ninety-five papers in full text were assessed, of which 83 were excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria. Finally (Fig. 1), a total of 12 pragmatic RCTs were included [49, 51, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

Studies description

Of the 12 studies identified as pragmatic, three were cluster randomised controlled trials (cRCT) [49, 51, 72] while the other nine were RCTs [67,68,69,70,71, 73,74,75,76].The duration of the studies varied between three [49, 67, 72, 76] and 14 months [68] with a mean length of 6.4 months (SD = 3.6). The sample size varied from 65 [70] to 6987 patients [49]. The mean number of patients included in the studies was 1029.75 (SD = 1892.0) with a median of 541.0.

The mean number of pharmacists per study delivering the intervention was 55.2 (SD = 37.5) although in one paper only one pharmacist was involved [76]. In six of the studies pharmacists were reimbursed for providing PPS [51, 68,69,70, 72, 74]. In seven of the 12 studies there was training for the intervention [49, 51, 69,70,71,72,73], either face-to-face, on-line or both, with a duration of between six and 48 h. In the remaining five studies [67, 68, 74,75,76] no training was delivered as the pharmacies or pharmcists were already accredited for PPS provision.

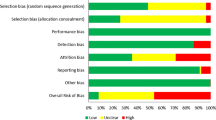

Degree of pragmatism and study quality

All eligible papers scored over 50% on the PRECIS-2 scale, which reinforced their external validity and were considered pragmatic. The scores ranged from 24.0/45 to 41.5/45 (Fig. 2). The highest value for each PRECIS-2 domain were obtained for Setting (average 4.6/5) and Primary analysis (average 3.8/5) while the lowest value was found in Organisation criteria (average 3.0/5). The complete assesesment of PRECIS-2 tool is available in the Additional file 1.

Assessment of pragmatic degree of trials using PRECIS-2 tool. Image shows PRECIS-2 wheels for PPS according to the degree of pragmatism: author; PPS: PRECIS-2 score out of 45. 1. Eligibility, 2. Recruitment, 3.Setting, 4.Organisation, 5. Flexibility (delivery), 6. Flexibility (adherence), 7. Follow-up, 8. Primary outcome, 9. Primary analysis

With respect to internal validity, nine papers stated confidence intervals or size effects for their main outcome indicators [49, 67, 68, 71,72,73,74,75,76]. Only three papers presented baseline differences between groups [70, 71, 75] and these used a statistical technique to adjust for such differences. In six out of the nine non cluster RCT, the authors recognized contamination risk between groups [68, 69, 71, 73,74,75]. Only one RCT used a blinded assessor [71]. Nine out of 12 analyses were based on intention to treat (ITT) [51, 67, 68, 70,71,72,73,74,75] whereas the remaining three were per protocol [49, 69, 76].

Type of PPSs

The PPSs reported were classified as eight different types [66]: Dispensing/Adherence service [71, 72]; Smoking cessation service [49]; New Medicine Service (NMS) [68]; Independent prescribing [74]; Medication Therapy Management (MTM) [67, 70, 76]; Clinical Medication Reviews (CMR) [69, 75]; Disease State Management (DSM) [51] and Pharmaceutical Care (PC) [73]. Since CMR [69, 75], DSM [51], PC [73] and MTM services [67, 70, 76] included a care plan, implying a continuous intervention and evaluation of patients’ outcomes, they were recategorized as MTM [77]. Therefore, five different types of PPSs were finally evaluated.

Pharmacists delivered the service by means of an individualized face to face consultation with patients [49, 51, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75], telephone contact [68, 76], or review of patient’s records without patient contact [67].

Four out of the 12 studies [49, 51, 72, 73] reported patients’ loss to follow up rates higher than 15%. The main causes of dropouts were hospitalization [73], inability to contact [75, 76], not giving informed consent [75], lost to follow up [49, 51, 67, 70, 71, 73], death [73, 75], not having time for the study and for no specific reason [67, 68, 74].

Further descriptions of the general characteristics of included articles are provided in Table 1.

Clinical, economic or humanistic outcomes of the interventions

Nine out of the 12 studies showed positive statistically significant differences in a clinical primary outcome that could be associated with four PPS: Smoking cessation [49], Dispensing/Adherence service [71], Independent prescribing [74] and MTM [51, 67, 69, 70, 73, 76]. The other three studies only achieved significant statistical improvements in subgroup analysis [75], secondary outcomes [72] and/or process indicators [68]. Description of the interventions and detailed clinical, economic or humanistic primary outcomes of papers included are provided in Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

Provision of specific PPSs achieved a statistically significant better control of several clinical outcome indicators: Independent prescribing improved blood pressure [74], Adherence service improved blood pressure [72], Smoking cessation improved abstinence from tobacco [49] and MTM improved pulmonary exacerbations [73], HbA1c [67, 70], CV risk [67], blood pressure [67, 69, 70, 72, 74], tobacco use [67], HDL [69] and LDL-cholesterol [67]. Additionally, eight papers showed a statistically significant improvement in process indicators of PPSs effectiveness, such as the inhaler technique [51, 73], adherence [51, 68, 71,72,73] or resolution of drug related problems (DRPs) [69, 75, 76]. MTM statistically decreased hospitalizations, bed-bound episodes and emergency room visits [67, 71, 73, 74, 76].

Humanistic outcomes

Three out of the five papers [51, 68, 71, 73, 75] measuring humanistic outcomes reported statistically significant improvements in Health-Related Quality of Life (HR-QoL) through the provision of Dispensing/ Adherence [71] and MTM services [51, 75]. In these three papers, HR-QoL was the primary outcome.

Economic outcomes

None of the papers involved any cost-effectiveness analysis. NMS [68] didn’t show a statistically significant reduction in National Health Service (NHS) costs.

Discussion

Stakeholders need pragmatic studies with high methodological quality to make evidenced based decisions on which services to fund. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first systematic review that evaluates evidence from pragmatic RCTs of the effectiveness of PPSs in the community pharmacy setting. One of the main strengths of this review is the use of the PRECIS-2 tool, which allowed the characterization of the level of pragmatism of the study designs. The PRECIS-2 tool had previously shown good reliability with modest discriminatory validity [60, 65]. Currently there are few pragmatic papers on PPSs and researchers should make wider use of this tool when designing their trials in an attempt to provide practice-based data on specific PPSs.

Setting was one of the highest scored domains within the studies, reflecting the ease of accessibility of community pharmacies to implement PPSs. The second most scored domain was the manner in which primary outcomes were assessed. Most of the studies used ITT which reinforced the external validity of their conclusions.

In contrast, the low score obtained in domains related to organisation criteria, recruitment and flexibility (adherence) suggests a need to implement strategies that enhance pharmacist training such as accreditation processes, training in communication skills and teaching of pragmatic methodologies [78,79,80,81]. According to our assessment, studies with the highest score of pragmatism were carried out in UK [68], Canada [74], Netherlands [75] and US [76], countries coinciding with those described by Mossialos et al. [2], as the most advanced PPSs providers. Probably these countries provide a more favorable environment for patient recruitment and PPSs implementation, with experience in service accreditation and remuneration.

Our findings reinforce previous conclusions on the effectiveness of PPSs [30, 82]. There was evidence (nine out of the 12 pragmatic RCT) that supports PPSs clinical effectiveness, specifically for prescribing interventions and MTM services. These two services achieved statistically significant improvements in a variety of intermediate clinical outcomes such as blood pressure, pulmonary exacerbations, HbA1c, CV risk, tobacco use, HDL and LDL- cholesterol. Other type of services (Dispensing /Adherence and NMS) did not report clinical effectiveness. The inherent methodologic components of the services, as well as other factors such as fidelity and duration of the intervention, may be related to favourable clinical outcomes. In Independent prescribing and MTM services, pharmacists assess patient clinical outcomes and develop interventions specifically tailored to individual patient’s health status. In contrast, pharmacists providing Dispensing/Adherence and NMS services focus their interventions predominantly on improving the medication use process (inhaler technique, DRP).

The two studies with the highest pragmatic scores, one evaluating a telephonic MTM service and the other assessing the NMS, did not demonstrate any positive results on hospitalizations nor medication adherence. This may be due, or related to, the short duration of the studies (3 months and 10 weeks respectively) or to the components of the service (i.g. telephonic follow-up). The additional components or factors that may make telephonic MTM or follow-up effective are unknown [83, 84].

There were three pragmatic studies supporting the effectiveness of PPSs (asthma DSM, Dispensing/Adherence and MTM) on humanistic indicators (HR-QoL) [51, 71, 75]. The studies that achieved statistically significant improvements had follow-up visits and assessed the effect at 6 months. These two components had been previously reported as critical in achieving a humanistic impact [34, 42, 82]. Therefore, studies measuring humanistic indicators should consider longer durations and follow-up periods.

Although there are many systematic reviews of PPSs cost-effectiveness, these are undertaken in explanatory RCTs [35, 36, 85]. In our review none of the papers fulfilling our selection criteria for pragmatism assessed cost-effectiveness. Three articles [68, 73, 76] reported other economic indicators but in none of these there was any significant statistical difference between groups. The importance to stakeholders of cost-effectiveness studies should not be underestimated since the sustainability of services might be dependent on delivering costs savings or cost-effectiveness to the healthcare system.

Two key methodological quality aspects should be considered when designing future pragmatic research. We found only one study that blinded outcome assessment, which may be considered as a potential bias that could overestimate PPS effectiveness. Half of the studies reported a risk of contamination, a very common threat in the assessment of complex interventions. Thus cluster designs controlling for potential risk of contamination should be considered.

This review has several limitations due to the assessment of pragmatism.The PRECIS-2 tool was applied after the screening process which allowed only the consideration of papers meeting our inclusion criteria. Since the PRECIS-2 tool suggests a continuum between explanatory and pragmatic and no minimum score is provided to classify a paper as pragmatic or explanatory, the selected cut-off point (22.5 out of 45) could be questioned.The PRECIS-2 tool although having good reliability has been reported to have modest discriminatort validity [60]. Another limitation relates to the variability of the different PPSs type and their outcomes making it difficult to make comparisons between studies. Future studies should select specific services to evaluate health outcomes using pragmatic approaches, using the PRECIS-2 tool to design the study.

Conclusions

There is a need for pragmatic studies to evaluate economic, clinical and humanistic outcomes of PPS as currently there is limited available evidence on the effectiveness of these services.

Although few pragmatic RCT were found, most of them showed evidence of clinical effectiveness. There is scarce evidence of humanistic and economic outcomes. The lack of an adequate number of pragmatic clinical trials may be problematic to provide evidence of the sustainability of the PPS. More focus and emphasis should be given to increase the level of evidence of economic, clinical and humanistic indicators from a pragmatic perspective.

Researchers should consider the level of pragmatism of their research design using the PRECIS-2 tool. This would allow them to ensure the applicability of their research.

Practical implications

There is limited evidence of PPS outcomes from pragmatic studies. Therefore there is a need to undertake further research on specific PPS, with patients under normal practice conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACQ:

-

Asthma Control Questionnaire

- ADH:

-

Adherence service

- CAT:

-

COPD Assessment Test

- CMR:

-

Clinical Medication Reviews

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- D/ADH:

-

Dipensing/Adherence service

- DRP:

-

Drug Related Problem

- DSM:

-

Disease State Management

- ECHO :

-

Economic, Clinic and Humanistic outcomes

- HEDIS:

-

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

- HR-QoL:

-

EuroQoL [EQ]-5D-5L

- MTM:

-

Medication Therapy Management

- NCQA :

-

National Committee for Quality Assurance

- IND.P:

-

Independent prescribing

- NHS:

-

National Health System

- NMS:

-

New Medicine Service

- NRT:

-

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

- PC:

-

Pharmaceutical Care

- PCI:

-

Pharmaceutical care issues

- PPS:

-

Professional Pharmacy Service

- RCT:

-

Randomised Control Trial

- SMOK:

-

Smoking cessation service

- TABS:

-

Tool for Adherence Behavior Screening

- VAS:

-

EQ-Visual Analogic Scale

References

Mossialos E, Naci H, Courtin E. Expanding the role of community pharmacists: policymaking in the absence of policy-relevant evidence? Health Policy. 2013;111(2):135–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.04.003.

Mossialos E, Courtin E, Naci H, Benrimoj S, Bouvy M, Sketris I, et al. From “retailers” to health care providers: transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy. 2015;119(5):628–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007.

World population ageing: 1950–2050 [Internet]. New York: United Nations; [Acceso Feb 2020]. Available in: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf.

WHO. Aging and life cycle. (Internet) (Accesed Nov 2019). Available in: http://www.who.int/ageing/about/facts/es/.

Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–43.

International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Improving global health by closing gaps in the development, distribution, and responsible use of medicines. Amsterdam: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2012. (Accesed Nov 2019). Available in: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/news/Centennial%20Declaration%20%20final%20version.pdf

Wiedenmayer K, Summers RS, Mackie CA, Gous AGS, Everard M, Tromp D. Developing pharmacy practice: a focus on patient care: handbook (no. WHO/PSM/PAR/2006.5). World Health Organization. The Hague: Ed. WHO and FIP; 2006.

Holland RW, Nimmo CM. Transitions, part 1: beyond pharmaceutical care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(17):1758–64.

Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. Defining professional pharmacy services in community pharmacy. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(6):989–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.02.005.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Cruden G, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215.

Perraudin C, Bugnon O, Pelletier-Fleury N. Expanding professional pharmacy services in European community setting: is it cost-effective? A systematic review for health policy considerations. Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1350–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.013.

Houle SK, Grindrod KA, Chatterley T, Tsuyuki RT. Paying pharmacists for patient care: a systematic review of remunerated pharmacy clinical care services. Can Pharm J. 2014;147:209–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163514536678.

Chan P, Grindrod KA, Bougher D, Pasutto FM, Wilgosh C, Eberhart G, Tsuyuki RT. A systematic review of remuneration systems for clinical pharmacy care services. Can Pharm J. 2008;141:102–12.

Anderson C, Sharma R. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in England. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(1):1870. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2020.1.1870.

Dineen-Griffin S, Benrimoj SI, Garcia-Cardenas V. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Australia. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(2):1967. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2020.2.1967.

Salgado TM, Rosenthal MM, Coe AB, Kaefer TN, Dixon DL, Farris KB. Primary healthcare policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in the United States. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(3):2160. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2160.

Raiche T, Pammett R, Dattani S, Dolovich L, Hamilton K, Kennie-Kaulbach N, McCarthy L, Jorgenson D. Community pharmacists’ evolving role in Canadian primary health care: a vision of harmonization in a patchwork system. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(4):2171. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2020.4.2171.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research—“blue highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.4.403.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Collins R, Bowman L, Landray M, Peto R. The magic of randomization versus the myth of real-world evidence. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(7):674–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb1901642.

Kennedy-Martin T, Curtis S, Faries D, Robinson S, Johnston J. A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials. 2015;16:495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4.

Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20(8):637–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0.

Boesen F, Nørgaard M, Trénel P, Rasmussen PV, Petersen T, Løvendahl B, et al. Longer term effectiveness of inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation on health-related quality of life in MS patients: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial - The Danish MS Hospitals Rehabilitation Study. Mult Scler. 2018;24(3):340–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517735188.

Wallis M, Marsden E, Taylor A, Craswell A, Broadbent M, Barnett A, et al. The geriatric emergency department intervention model of care: a pragmatic trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0992-z.

Williams HC, Burden-Teh E, Nunn AJ. What is a pragmatic clinical trial? J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(6):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.134.

Kooij MJ, Heerdink ER, van Dijk L, van Geffen EC, Belitser SV, Bouvy ML. Effects of telephone counseling intervention by pharmacists (TelCIP) on medication adherence; results of a cluster randomized trial. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00269.

Barnish MS, Turner S. The value of pragmatic and observational studies in health care and public health. Pragmat Obs Res. 2017;8:49–55. https://doi.org/10.2147/POR.S137701.

Clancy CM. Comparative effectiveness research: promising area of study for pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2010;50(2):131–3. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2010.10501.

Carter BL, Foppe van Mil JW. Comparative effectiveness research: evaluating pharmacist interventions and strategies to improve medication adherence. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(9):949–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2010.136.

Sáez-Benito L, Fernandez-Llimos F, Feletto E, Gastelurrutia MA, Martinez-Martinez F, Benrimoj SI. Evidence of the clinical effectiveness of cognitive pharmaceutical services for aged patients. Age Ageing. 2013;42(4):442–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft045.

Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brillant M, Burton D, Emmerton L, Krass I, et al. Pharmacy asthma care program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax. 2007;62(6):496–502. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.064709.

Gordois A, Armour C, Brillant M, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Burton D, Emmerton L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a pharmacy asthma care program in Australia. Dis Manag Health Out. 2007;15:387–96.

Bunting BA, Cranor CW. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes of a community-based medication therapy management program for asthma. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2006;46(2):133–47. https://doi.org/10.1331/154434506776180658.

Yaghoubi M, Mansell K, Vatanparastc H, Steeves M, Zeng W, Farag M. Effects of pharmacy-based interventions on the control and management of diabetes in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(6):628–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.09.014.

Jódar-Sánchez F, Malet-Larrea A, Martín JJ, García-Mochón L, López Del Amo MP, Martínez-Martínez F, et al. Cost-utility analysis of a medication review with follow-up service for older adults with polypharmacy in community pharmacies in Spain: the conSIGUE program. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(6):599–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0270-2.

Malet-Larrea A, Goyenechea E, García-Cárdenas V, Calvo B, Martínez-Martínez F, Benrimoj SI, et al. The impact of a medication review with follow-up service on hospital admissions in aged polypharmacy patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:831–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13012.

Zermansky AG, Silcock J. Is medication review by primary-care pharmacists for older people cost effective?: a narrative review of the literature, focusing on costs and benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200927010-00003.

Schumock GT, Butler MG, Meek PD, Vermeulen LC, Arondekar BV, Bauman JL. Evidence of the economic benefit of clinical pharmacy services: 1996-2000. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(1):113–32. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.23.1.113.31910.

Fera T, Bluml BM, Ellis WM. Diabetes ten City challenge: final economic and clinical results. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2009;49:383–91. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09015.

Ramalho de Oliveira D, Brummel AR, Miller DB. Medication therapy management: 10 years of experience in a large integrated health care system. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:185–95. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.185.

Malet-Larrea A, Goyenechea E, Gastelurrutia MA, García-Cárdenas V, Cabases JM, Noain A, et al. Cost analysis and cost-benefit analysis of a medication review with follow-up service in aged polypharmacy patients. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(9):1069–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0853-7.

Loh ZW, Cheen MH, Wee HL. Humanistic and economic outcomes of pharmacist-provided medication review in the community-dwelling elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(6):621–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12453.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Treweek S, Zwarenstein M. Making trials matter: pragmatic and explanatory trials and the problem of applicability. Trials. 2009;10:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-10-37.

McLean W, Gillis J, Waller R. The BC Community Pharmacy Asthma Study: a study of clinical, economic and holistic outcomes influenced by an asthma care protocol provided by specially trained community pharmacists in British Columbia. Can Respir J. 2003;10(4):195–202. https://doi.org/10.1155/2003/736042.

Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2003;43:173–84. https://doi.org/10.1331/108658003321480713.

Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290:1624–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.12.1624.

Maclure M. Explaining pragmatic trials to pragmatic policymakers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:476–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.021.

Costello MJ, Sproule B, Victor JC, Leatherdale ST, Zawertailo L, Selby P. Effectiveness of pharmacist counseling combined with nicotine replacement therapy: a pragmatic randomized trial with 6,987 smokers. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:167–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9672-9.

Ware JH, Hamel MB. Pragmatic trials—guides to better patient care? N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1685–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1103502.

Armour CL, Reddel HK, LeMay KS, Saini B, Smith LD, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an evidence-based asthma service in Australian community pharmacies: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J Asthma. 2013;50:302–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2012.754463.

Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:499–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.012.

Liberati A. The relationship between clinical trials and clinical practice: the risks of underestimating its complexity. Stat Med. 1994;13:1485–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780131326.

Tosh G, Soares-Weiser K, Adams CE. Pragmatic vs explanatory trials: the pragmascope tool to help measure differences in protocols of mental health randomized controlled trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(2):209–15.

Patsopoulos NA. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:217–24.

Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, Lohr KN, Carey TS. A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1040–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.011.

Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, Treweek S, Furberg CD, Altman DG, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:464–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011.

Koppenaal T, Linmans J, Knottnerus JA, Spigt M. Pragmatic vs. explanatory: an adaptation of the PRECIS tool helps to judge the applicability of systematic reviews for daily practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(10):1095–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.020.

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness. York (UK): CRD’s guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews, University of York; 2009. ISBN.978–1–900-640-47-3

Loudon K, Zwarenstein M, Sullivan FM, Donnan PT, Gágyor I, Hobbelen HJSM, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool has good interrater reliability and modest discriminant validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:113–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.001.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Kozma CM, Reeder CE, Schulz RM. Economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes: a planning model for pharmacoeconomic research. Clin Ther. 1992;15:1121–32.

Ramsberg J, Platt R. Opportunities and barriers for pragmatic embedded trials: triumphs and tribulations. Learn Health Syst. 2017;2(1):e10044. https://doi.org/10.1002/lrh2.10044.

Bradley AJ, Lenox-Smith AJ. Does adding noradrenaline reuptake inhibition to selective serotonin reuptake inhibition improve efficacy in patients with depression? A systematic review of meta-analyses and large randomised pragmatic trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(8):740–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113494937.

Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2147.

Benrimoj SI, Feletto E, Gastelurrutia MA, Martínez-Martinez F, Faus MJ. A holistic and integrated approach to implementing cognitive pharmaceutical services. Ars Pharm. 2010;51:69–87.

Al Hamarneh YN, Hemmelgarn BR, Hassan I, Jones CA, Tsuyuki RT. The effectiveness of pharmacist interventions on cardiovascular risk in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: the multicentre randomized controlled RxEACH trial. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(6):580–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.08.244.

Elliott RA, Boyd MJ, Salema NE, Davies J, Barber N, Mehta RL, et al. Supporting adherence for people starting a new medication for a long-term condition through community pharmacies: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the new medicine service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(10):747–58. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004400.

Geurts MM, Stewart RE, Brouwers JR, de Graeff PA, de Gier JJ. Implications of a clinical medication review and a pharmaceutical care plan of polypharmacy patients with a cardiovascular disorder. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):808–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0281-x.

Planas LG, Crosby KM, Farmer KC, Harrison DL. Evaluation of a diabetes management program using selected HEDIS measures. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52(6):e130–8. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2012.11148.

Rubio-Valera M, Pujol MM, Fernández A, Peñarrubia-María MT, Travé P, Del Hoyo YL, et al. Corrigendum to: “Evaluation of a pharmacist intervention on patients initiating pharmacological treatment for depression: a randomized controlled superiority trial” [Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23(2013)1057-1066]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(6):1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.02.016.

Stewart K, George J, Mc Namara KP, Jackson SL, Peterson GM, Bereznicki LR, et al. A multifaceted pharmacist intervention to improve antihypertensive adherence: a cluster-randomized, controlled trial (HAPPy trial). J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(5):527–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12185.

Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Van Hees T, Adreiaens E, Van Bortel L, Christiaens T, et al. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PHARMACOP): a randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):756–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12242.

Tsuyuki RT, Houle SK, Charrois TL. Randomized trial of the effect of pharmacist prescribing on improving blood pressure in the community: the Alberta clinical trial in optimizing hypertension (RxACTION). Circulation. 2015;132(2):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015464.

Verdoorn S, Kwint HF, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. Effects of a clinical medication review focused on personal goals, quality of life, and health problems in older persons with polypharmacy: a randomised controlled trial (DREAMeR-study). PLoS Med. 2019;16(5):e1002798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002798.

Zillich AJ, Snyder ME, Frail CK, Lewis JL, Deshotels D, Dunham P, et al. A randomized, controlled pragmatic trial of telephonic medication therapy management to reduce hospitalization in home health patients. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1537–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12176.

Oladapo AO, Barner JC, Rascati KL. The need for more evidence-based studies to justify the economic value for the provision of medication therapy management and other clinical pharmacy services. Clin Ther. 2012;34:2196–9.

Gastelurrutia MA, Fernández-Llimós F, García-Delgado P, Gastelurrutia P, Faus MJ, Benrimoj SI. Barriers and facilitators to the dissemination and implementation of cognitive services in Spanish community pharmacies. Seguim Farmacoter. 2005;3(2):65–77.

Roberts AS, Benrimoj SI, Chen TF, Williams KA, Hopp TR, Aslani P. Understanding practice change in community pharmacy: a qualitative study in Australia. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2005;1(4):546–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.09.003.

Houle SK, Charrois TL, Faruquee CF, Tsuyuki RT, Rosenthal MM. A randomized controlled study of practice facilitation to improve the provision of medication management services in Alberta community pharmacies. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(2):339–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.02.013.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1312.

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: an overview of systematic reviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):661–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.08.005.

DeZeeuw EA, Coleman AM, Nahata MC. Impact of telephonic comprehensive medication reviews on patient outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(2):e54–8.

Beran M, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, Crabtree B, Green BB, Groen SE, et al. Key components of success in a randomized trial of blood pressure telemonitoring with medication therapy management pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2013). 2018;58(6):614–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2018.07.001.

Dawoud DM, Haines A, Wonderling D, Ashe J, Hill J, Varia M, et al. Cost effectiveness of advanced pharmacy services provided in the community and primary care settings: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(10):1241–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00814-4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the manuscript. MAG, LSB and RVD carried out the selection process and the discussion for the decision of the PPS articles. RVD and MAG reviewed the literature. LSB resolved disagreements. SIB, VGC and FMM revised the paper and made improvements.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The complete assessment of pragmatic degree of trials using of PRECIS 2-tool

Appendix

Appendix

Search strategy used in the other databases.

COCHRANE:

((pragmatic[All Fields] OR (naturalistic[All Fields]) OR (“Comparative Effectiveness Research”[Mesh] OR “Pragmatic Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh]) AND (“pharmaceutical care”[tiab] OR “medication review”[tiab] OR “Community Pharmacy Services”[Mesh] OR “Drug Utilization Review”[Mesh] OR “Medication Therapy Management”[Mesh] OR “clinical pharmacy service”[All Fields] OR “pharmacists”[MeSH Terms])

EMBASE:

(pragmatic OR naturalistic) AND (Pharmaceutical Care OR medication therapy management OR clinical pharmacy OR pharmacists OR Community Pharmacy or Drug Utilization Review)*.

* Those in bold are Embase Emtree terms.

SCIELO:

(Pragmático or naturalistico or efectividad) AND (servicios profesionales OR atención farmacéutica OR seguimiento farmacoterapéutico OR revisión de la farmacoterapia OR farmacéutico OR farmacia comunitaria OR gestión de la medicación OR revisión del uso del medicamento)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Varas-Doval, R., Saéz-Benito, L., Gastelurrutia, M.A. et al. Systematic review of pragmatic randomised control trials assessing the effectiveness of professional pharmacy services in community pharmacies. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 156 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06150-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06150-8