Abstract

Background

Indigenous Australians experience high rates of chronic conditions. It is often asserted Indigenous Australians have low adherence to medication; however there has not been a comprehensive examination of the evidence. This systematic literature review presents data from studies of Indigenous Australians on adherence rates and identifies supporting factors and impediments from the perspective of health professionals and patients.

Methods

Search strategies were used to identify literature in electronic databases and websites. The following databases were searched: Scopus, Medline, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, Cochrane Library, Trove, Indigenous Health infonet and Grey Lit.org. Articles in English, reporting original data on adherence to long-term, self-administered medicines in Australia’s Indigenous populations were included.

Data were extracted into a standard template and a quality assessment was undertaken.

Results

Forty-seven articles met inclusion criteria. Varied study methodologies prevented the use of meta-analysis. Key findings: health professionals believe adherence is a significant problem for Indigenous Australians; however, adherence rates are rarely measured. Health professionals and patients often reported the same barriers and facilitators, providing a framework for improvement.

Conclusions

There is no evidence that medication adherence amongst Indigenous Australians is lower than for the general population. Nevertheless, the heavy burden of morbidity and mortality faced by Indigenous Australians with chronic conditions could be alleviated by enhancing medication adherence. Some evidence supports strategies to improve adherence, including the use of dose administration aids. This evidence should be used by clinicians when prescribing, and to implement and evaluate programs using standard measures to quantify adherence, to drive improvement in health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and kidney disease impair the health of many Aboriginal Australian and/or Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter the term ‘Indigenous’ is used). In 2012–13, an estimated 20% of Indigenous Australian adults had high blood pressure, 25% had elevated cholesterol and 18% had indicators of chronic kidney disease [1]. Chronic conditions lead to considerable morbidity and premature mortality, contributing to 80% of the difference in life expectancy between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians [2].

Management of chronic conditions usually requires a combination of behaviour modification and taking prescription medicines; accordingly effective management relies in part on medication adherence. The determinants of adherence to medicines are complex and incorporate human behaviour, health literacy and adequate access to resources to support adherence. Not surprisingly, numerous studies in the ‘general’ population indicate that when adherence is suboptimal health outcomes are poorer [3]. Indigenous Australians continue to die almost ten years earlier than non-Indigenous Australians [1]. The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia recently stated that inadequate medication adherence will impede improvements in the life expectancy for Indigenous Australians living with chronic conditions [4] and many health professionals and researchers assert that adherence in this population is especially challenging. Two thirds of Indigenous Australians have at least one chronic condition [1] but there has been limited objective examination of the contribution of adherence to medicines to chronic condition management in this population. Very few studies have quantified adherence for this population or examined the association between adherence and clinical outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Adherence in the context of Indigenous health in Australia has been reviewed previously, though not systematically nor focusing on chronic conditions, and no attempts to assess the quality of the existing literature have been made. Davidson et al. identified cost of medications, patient mobility and ‘culturally alienating’ health services as barriers to adherence, and recommended adherence support strategies including regimen simplification, use of dose administration aids (DAAs) and building the cultural competence of health professionals to strengthen relationships with patients [5]. A review in the Medical Student Journal of Australia noted that inadequate family support and culturally inappropriate service delivery could all impair adherence [6]. Strategies suggested for supporting adherence included training health professionals in ‘cultural values and healthcare beliefs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’, increased use of interpreters and the subsidisation of medications for Indigenous Australians [6]. While many Indigenous Australians (35%) live in major city areas, the majority (44%) live in regional areas and 21% live in remote areas [7], so all health services in Australia need to provide culturally appropriate care.

In this era of escalating prevalence of chronic conditions, especially in populations of Indigenous Australians, clinicians and researchers require high-quality evidence to guide approaches to optimising adherence. The data on adherence rates for this population are often based on anecdote and information on appropriate strategies requires collation and analysis so that recommendations can be made.

Therefore we aimed to undertake a systematic literature review to provide a comprehensive compilation and examination of the literature on adherence to long-term medicines by Indigenous Australians living with chronic conditions. The primary objectives were: to synthesise data on the rates of adherence to medicines; explore health professionals’ attitudes towards adherence, and examine the impediments to and supporting factors of adherence as reported by health professionals and patients. The secondary objective was to identify and collate data on the health outcomes associated with adherence.

Methods

The review was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines [8].

Eligibility criteria

Studies and evaluations of any design reporting original data on adherence to self-administered medicines for chronic conditions were included. The authors were aware that very few randomised controlled trials had been conducted to examine this issue, so a deliberately broad inclusion criterion was applied regarding study methodology. The study population had to include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Australians and results needed to be disaggregated by ethnicity. Eligible clinical trials and intervention studies were included in the facilitators and barriers section; only baseline adherence rates from these studies (where reported) were included in the compilation of adherence rate data since adherence during clinical trials is often higher than in real-world settings [9]. To maximise information available on health professionals’ perspectives commentary pieces by experts in the field were also included. Results were limited to articles published in English.

Most people with chronic conditions rely on self administered medications to manage their health, so studies reporting adherence to dialysis, chemotherapy and radiation therapy and directly administered medications (such as Benzathine Penicillin G injections) were excluded. Treatment and prophylaxis for tuberculosis were included as these treatment regimens are prolonged.

Information sources and search strategy

Articles were identified through database searches, citation searching and review by experts. The electronic databases searched were: Scopus, Medline, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, Cochrane Library, National Library of Australia (Trove) (limited to books and theses), Indigenous Health infonet, and Grey Lit.org, from inception until 23 February 2015. In addition the Charles Darwin University library catalogue was searched and a Google search was conducted (limited to sites ending in .gov.au or org.au, the first ten pages of results reviewed). A shortlist of relevant references was distributed to experts in the field who were asked to identify any missing publications. In addition the reference lists of included articles were searched.

The search strategy was kept intentionally broad to ensure all data relevant to chronic conditions were included. The search strategy for Medline was: (((*adheren* OR *complian* OR concord*) and (treatment* or medicine* OR medication* OR drug*)) or (MM “Patient Compliance+” OR MM “Medication Adherence”and (indigenous or aborigin* or “torres strait” or MH “Oceanic Ancestry Group”). Limited to English language. See Additional file 1 for full details of the search strategy.

Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

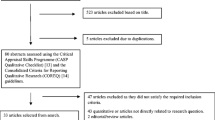

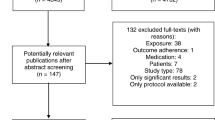

Data elements extracted were: study aim, methodology, site, dates; participant eligibility criteria; recruitment strategy; sample size; data collection method; data analysis strategy; results. Study quality was assessed using a tool adapted from McInnes and Chambers [10] (see Additional file 2). The study quality criteria were not applied to evaluation reports, correspondence or commentary pieces. Due to the limited data available on the subject, study quality score was not used to exclude articles or weight study findings. Data extraction and quality assessment were completed by the first author. Findings from qualitative studies were compiled in a narrative synthesis. See Fig. 1 below for a flowchart of the article selection process.

Results

The 47 included articles reported on people living with: HIV, diabetes, epilepsy, kidney disease, mental health issues, tuberculosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease and those who had experienced a seizure. Five sources reported rates of adherence and 14 reported barriers, facilitators or strategies, either from the patient or health professional perspective. Participants from all states and territories except the Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania were represented. The characteristics, results and quality scores for the journal articles are included in Table 1 below (when multiple articles reported on the same study the information has been combined). Summaries of the evaluation reports and letter in reply can be found at Additional file 3; commentary pieces were not summarised.

Study quality scores ranged from −4 to +96% (median: 54; IQR: 39). The criteria could not be applied to one study due to the absence of any methodological information on the assessment of adherence [11]. The most common issue was incomplete methodology reporting.

Adherence rates

Six articles included quantified adherence rates and these studies reported that approximately two thirds of Indigenous Australians take their regular medications at least some of the time (rates and definitions from individual studies are listed in Table 1) [12,13,14,15,16,17]. The methods used to quantify adherence were rarely reported in detail and studies differed in the way they quantified or categorised adherence; consequently a meta-analysis was not possible and comparison of findings was difficult.

Two of these studies found that Indigenous Australians were less adherent than non-Indigenous Australians [12, 13]. These findings were based on self-reported adherence. and we did not identify any studies validating self-reported adherence in this population so the accuracy of the data is unclear.

Outcomes of adherence

Few studies have explored associations between adherence and clinical outcome, or sought Indigenous Australians’ views on this relationship. Some authors attributed poor clinical outcomes (including relapse of tuberculosis; failure of a kidney graft; recurrence of angina after heart surgery; and death after heart surgery) to inadequate adherence [18,19,20] and 82.9% of health professionals working in mental health services in the NT reported inadequate adherence as a common cause of relapse [21]. Predictors of clinical outcome are multifactorial, for example, poor clinical outcomes in Indigenous Australians with diabetes have been attributed to clinical inertia and inadequate dose titration rather than adherence problems [15].

In a study of cultural beliefs of disease causation (specifically, cultural factors affecting renal transplant outcome), just one patient connected their inadequate adherence to a negative health outcome (graft rejection); other patients instead nominated factors such as alcohol, poor nutrition and separation from kin and country as causes of poor health outcomes [22].

Attitudes about adherence rates

In the majority of studies, health professionals expressed the view that Indigenous Australians have inadequate adherence to medications [23, 24] and this is having a negative impact on Indigenous health in Australia [22, 24,25,26,27]. In one sample 97% of health professionals believed it was a ‘major or significant’ problem [28]. Just one study reported a positive view of adherence, with an Aboriginal Health Practitioner saying that ‘a good percentage are compliant’ [25].

Many health professionals acknowledged the challenges faced by Indigenous Australians taking long-term medicines, but there were mixed views on patients’ attitudes to medicines and adherence [29,30,31]. No studies reported patients’ own perceptions of their adherence.

Barriers to adherence

The literature reports numerous challenges experienced by Indigenous Australians requiring long-term medicines, with much agreement between providers and patients. Barriers reported by both patients and health professionals were: having other priorities including sociocultural obligations which were more important than taking medicines and often involved travelling away from their community; [32,33,34,35,36] cost; [25, 27, 30, 37,38,39] sharing or swapping medicines; [27, 29, 30, 37, 40,41,42] stopping medicines once feeling better [25, 40] and issues obtaining medicines while away from home [33, 43, 44].

An issue reported by patients only was forgetting to take doses [31, 40, 45, 46] and a few participants stated that their belief in God meant they did not need to take medicines [44,45,46]. In addition, health professionals reported that inadequate safe storage for medicines at home impaired adherence [30, 47].

Enablers of adherence

Dose administration aids (DAAs) and other simple strategies have been associated with improved adherence for Indigenous Australians. Patients in two studies reported that DAAs were useful, [33, 48] and in a small (n = 11) Central Australian study, the provision of DAAs increased patient adherence from 70% to 87% (p = 0.019). [16] Patients with HIV indicated that adjusting quantity/timing of alcohol consumption assisted with adherence, [49] and patients with diabetes indicated once-daily dosing assisted [48]. Health professionals reported that a good understanding of Western medicine and establishing good rapport with patients was associated with good adherence [28].

Approaches which engaged communities, and involved Aboriginal Health Practitioners and family, appeared to improve adherence. For example, increased availability of Aboriginal Health Practitioners was associated with higher adherence to tuberculosis treatment in northern Queensland [19] and was part of a successful strategy implemented at an Indigenous Health Service in Brisbane [36]. The involvement of community members in medication dispensing in a remote NT community was also associated with increased adherence [43]. Both health professionals and patients reported that family support enhanced adherence [28, 33].

Medication cost reductions via the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme co-payment, have alleviated the financial burden and reportedly improved adherence [43, 50].

Suggested strategies to improve adherence

The health professionals and participants interviewed in the eligible studies suggested a variety of approaches which they felt would enhance adherence; the proposed strategies aligned well with the barriers and facilitators described. Both groups felt that culturally appropriate resources designed to enhance the provision of patient education about medicines would increase adherence [17, 24, 33, 40, 51, 52]. Patients also suggested the establishment of a support group [45, 46]. Health professionals proffered a variety of adherence support strategies: increased involvement of Aboriginal Health Practitioners in medication management; [24, 52,53,54] simplification of dose regimens, including once-daily dosing and long acting formulations; [17, 35, 36, 52, 54,55,56] provision of DAAs, [27, 37, 52, 55] and the use of home medicines reviews [24, 42, 51] (although adaptation of this program is required to suit the needs of Indigenous Australians [25]). Some health professionals also emphasised the need to address social determinants of health [17, 27, 37, 54].

A summary of the opportunities to improve adherence is provided in Table 2.

Discussion

We identified a range of publications addressing adherence among Indigenous Australians. The articles varied widely in research methodology and quality, preventing a meta-analysis, and some of the sample sizes were small (two studies each with 11 participants). However, despite differences in study design and quality, many findings were remarkably similar, indicating the value of including all eligible studies for this review.

Adherence rates

Health professionals were essentially unanimous in seeing inadequate adherence as an important issue in Indigenous health in Australia, but just two studies reported results which support the assertion that adherence for Indigenous Australians is significantly worse than for non-Indigenous Australians [12, 13]. A number of studies found that two thirds of Indigenous Australians were adherent (based on varying definitions of ‘adherence’) [14, 16, 17], which aligns with findings of international studies across a range of populations and health conditions [57]. The potential discrepancy between provider beliefs and reality requires clarification through further studies using validated methods to measure adherence.

Barriers and facilitators of adherence

There was considerable overlap in the barriers and facilitators reported by health professionals and Indigenous Australians living with chronic conditions, indicating that many health professionals are aware of the challenges faced by their patients. Some patients reported that traditional or religious beliefs could cause or prevent ill health [22, 44,45,46] supporting the call for improved health literacy made by consumers and practitioners working in Indigenous health in Australia [17, 24, 33, 40, 51, 52]. Some very context-specific barriers were identified, such as adherence challenges for remote-dwelling Indigenous Australians during travel away from home communities [32,33,34,35,36], however many barriers to adherence faced by Indigenous Australians are universal. Forgetting doses, complex dosing schedules, the cost of medicines, inadequate social support and alcohol use were all identified as key factors in a 2008 international review of adherence [58]. This study also found that minority groups had poorer compliance, but concluded that socio-economic status was more likely to explain lower compliance than race [58].

Strategies to enhance adherence

The studies provided a range of suggested and proven adherence support strategies relevant for Indigenous Australians however there was only one example of a strategy being tested and evaluated in a research study (see Additional file 3 for details) [16]. Two other studies suggest there could be further scope for pill burden minimisation for Indigenous Australians. The Kanyini GAP study (not included in this review because results were not disaggregated by ethnicity) showed that dose regimen simplification (through the use of a polypill) can enhance adherence in a population with a large proportion of Indigenous Australians [59, 60]. Dose simplification also improved adherence in a New Zealand study which included a large proportion (50%) of Maori participants [61].

Other intervention studies testing adherence support strategies for Indigenous Australians have been published [62,63,64,65] or are being undertaken [66]; they provide relevant insights such as the value of directly-observed treatment, but did not meet the selection criteria for this review.

Specificity of findings

Some of the findings reported in this review may be specific to the study context – findings from remote settings for instance should not be extrapolated to Indigenous Australians living in urban areas, however it is worthwhile highlighting the consistency in information reported which was perhaps unexpected given the diversity of participant groups, which varied by condition, location, sex and age. Our findings are supported by previous non-systematic reviews of adherence among Indigenous Australians [5, 6].

Remaining evidence gaps

Unfortunately few papers accurately quantified adherence and just five articles linked adherence to clinical outcomes (none of which reported any statistical results). Consequently the size of the problem, the validity of health professional perspectives and the potential gains which could be achieved by focusing on adherence support strategies remain unknown. In addition, very limited information has been collected from Indigenous Australians who live in remote communities and those who do not speak English fluently; so further research is required to capture their views [67].

While many solutions can be identified from the international literature, specific locally-relevant strategies are also needed. It is heartening to see some translation of research findings into practice; the 2005 National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines for strengthening cardiac rehabilitation of Indigenous Australians includes evidence-based strategies for adherence support [68]. Continuing concerns about adherence and the ongoing significant burden caused by cardiovascular disease [69] and the absence of evidence-based recommendations for the management of other chronic conditions indicate more needs to be done.

We need more evidence on which activities effectively support Indigenous Australians requiring long-term medicines. This review indicates we have the necessary information to develop tailored, locally-relevant strategies.

Strengths and limitations

The key strengths of this review are the inclusion of qualitative and quantitative studies, the inclusion of grey literature and the use of a quality assessment tool. A limitation of this study is that initial study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were conducted by one individual (J.L.dD), however ongoing input from researchers with experience in systematic literature reviews and chronic conditions ensured the rigour of the implementation of the methodology and the results.

Conclusions

‘Closing the gap’ in health outcomes for Indigenous Australians with chronic conditions requires lifestyle modification, changes in health-seeking behaviour and adherence support. Data on adherence rates are limited, but it is likely that, as is the case in many patient populations, suboptimal adherence means that Indigenous Australians are not receiving the full benefit of medications. The maximum benefit of medications for chronic conditions is obtained with 100% adherence and in some chronic conditions such as HIV and rheumatic heart disease, missed or late doses can be particularly harmful. Therefore the target adherence for all people living with chronic conditions should be 100%.

This review informs clinical practice in several key ways. Clinicians who presume low adherence among Indigenous Australian patients, and may choose not to prescribe certain medications based on this presumption, need to acknowledge that this belief is not evidence-based. Clinicians prescribing for Indigenous Australians need to utilise methods which improve medication adherence, including dose administration aids. Additionally, methods which Indigenous Australians have requested or practitioners have suggested (Table 2) should be incorporated, including involving Indigenous health practitioners, using family- and community-centred approaches, and culturally-appropriate educational resources to achieve good rapport.

This review also informs future research priorities. Rigorous measurement and reporting of adherence using standard measures is needed and this could be achieved by using routinely collected dispensing data to calculate the medication possession ratio (an indicator widely used in adherence research). Randomised controlled trials of interventions, incorporating strategies such as those described herein would provide the robust data needed in this field to be able to improve adherence and therefore improve outcomes among people with chronic conditions.

In addition to gathering adherence data, existing information on facilitators should be used to develop, implement and evaluate interventions. Policy makers and health service managers should allocate appropriate resources for program delivery and evaluation and the findings should be published with detailed methodology information to maximise the evidence base.

Finally, the term ‘adherence’ itself may not be ideal, since it fails to acknowledge the partnership required to optimise chronic condition management. The focus should be on the development and maintenance of a respectful, trusting relationship between patient and health professional, one that is not overshadowed by assumptions of poor adherence.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015. Cat. no. IHW 147. Canberra: AIHW, 2015.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease: Australian facts. Cardiovascular disease series. Cat. no. CVD 53. Canberra: AIHW. 2011 12 August 2015. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-disease/cardiovascular-disease-australian-facts-2011/contents/table-of-contents.

Boswell KA, Cook CL, Burch SP, Eaddy MT, Ron Cantrell C. Associating medication adherence with improved outcomes: a systematic literature review. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2012;4(4):e97–e108.

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National Commission of audit - submission by the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Deakin, ACT: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; 2013.

Davidson PM, Abbott P, Davison J, DiGiacomo M. Improving medication uptake in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples. Heart Lung Circul. 2010;19(5–6):372–7.

Kumble S. Improving medication adherence amongst aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples. Australian medical student. Journal. 2014;4(2):79–82.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011 2013 [updated 27 January 2016; cited 2017 23 May]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3238.0.55.001Main+Features1June%202011?OpenDocument.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2009;339:b2535.

Epstein RS. Medication adherence: hope for improvement? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):268–70.

McInnes RJ, Chambers JA. Supporting breastfeeding mothers: qualitative synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(4):407–27.

Hoy WE, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, Scheppingen J, Sharma S, Katz IA. Chronic disease outreach program for aboriginal communities. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;68(98):S76–82.

Davis TME, McAullay D, Davis WA, Bruce DG. Characteristics and outcome of type 2 diabetes in urban aboriginal people: the Fremantle diabetes study. Intern Med J. 2007;37(1):59–63.

Wilson IB, Hawkins S, Green S, Archer JS. Suboptimal anti-epilepsy drug use is common among indigenous patients with seizures presenting to the emergency department. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(1):187–9.

Hoy WE, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan SN, Nicol JL. Clinical outcomes associated with changes in a chronic disease treatment program in an Australian aboriginal community. Med J Aust. 2005;183(6):305–9.

Johnson DR, McDermott RA, Clifton PM, D’Onise K, Taylor SM, Preece CL, et al. Characteristics of indigenous adults with poorly controlled diabetes in north Queensland: implications for services. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(325)

Davis R, Scholz A, Muller R, Charlesworth K. Evaluation of two interventions to assist medication concordance in a remote aboriginal community. National Prescribing Service: A Report for the National Prescribing Service; 2002.

Bryce S. Lessons from East Arnhem land: improving adherence to chronic disease treatments. Aust Fam Phys. 2002;31(7):617–21.

Kejriwal NK, Tan JTH, Vasudevan A, Ong M, Newman MAJ, Alvarez JM. Follow-up of Australian aboriginal patients following open-heart surgery in Western Australia. Heart Lung Circul. 2004;13(1):70–3.

Simpson G, Knight T. Tuberculosis in far North Queensland, Australia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3(12):1096–100.

Pugsley D. Dialysis and transplantation in the aboriginal population of South Australia and the northern territory. Queen Elizabeth Hospital: Adelaide; 1989.

Nagel T. The need for relapse prevention strategies in top end remote indigenous mental health. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health. 2006;5(1)

Bennett E, Manderson L, Kelly B, Hardie I. Cultural factors in dialysis and renal transplantation among aborigines and Torres Strait islanders in north Queensland. Aust J Public Health. 1995;19(6):610–5.

Stoneman J, Taylor SJ. Pharmacists' views on indigenous health: is there more that can be done? Rural Remote Health. 2007;7(3):743. Epub 2007 Aug 9

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Submission to the NSW legislative council's standing committee on social issues. Enquiry into the life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. 2008.

Campbell Research & Consulting. Home Medicines Review Program Qualitative Research Project - Final Report Victoria Campbell Research & Consulting, 2008.

Eley DS, Hunter K. Building service capacity within a regional district mental health service: recommendations from an indigenous mental health symposium. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(1):448.

Kowanko I, De Crespigny C, Murray H. Better medication management for aboriginal people with mental health disorders and their carers - final report 2003. Adelaide: Flinders University School of Nursing and Midwifery and the Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council; 2003.

Humphery K, Weeramanthri T, Fitz J. Forgetting compliance. Darwin: Northern Territory University Press; 2001.

Hamrosi K, Taylor SJ, Aslani P. Issues with prescribed medications in aboriginal communities: aboriginal health workers' perspectives. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(2):557.

Emden C, Kowanko I, De Crespigny C, Murray H. Better medication management for indigenous Australian: findings from the field. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2005;11:80–90.

Cribbes M, Glaister K. It's not easy' - caring for aboriginal clients with diabetes in remote Australia. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession. 2007;25(1–2):163–72.

Anderson K, Devitt J, Cunningham J, Preece C, Cass A. "All they said was my kidneys were dead": indigenous Australian patients' understanding of their chronic kidney disease. Med J Aust. 2008;189(9):499–503.

Swain L, Barclay L. They've given me that many tablets, I'm bushed. I don't know where I'm going. Austr. J Rural Health. 2013;21(4):216–9.

King M. The diabetes health care of aboriginal people in South Australia (part 1). Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession. 2001;10(3/4):147–55.

Sanburg A. An evaluation of the home medicines review (HMR) process at the Pika Wiya aboriginal health service (PWHS). RGH Pharmacy Consulting Services Pty Ltd: South Australia; 2009.

Jeremy R, Tonkin A, White H, Riddell T, Brieger D, Walsh W, et al. Improving cardiovascular Care for Indigenous Populations. Heart Lung Circul. 2010;19(5/6):344–50.

Kowanko I, de Crespigny C, Murray H, Groenkjaer M, Emden C. Better medication management for aboriginal people with mental health disorders: a survey of providers. Austr. J Rural Health. 2004;12(6):253–7.

Lake P. Assisting aboriginal patients with medication management. Aust Prescr. 2006;29:59–62.

Whitty JA, Sav A, Kelly F, King MA, McMillan SS, Kendall E, et al. Chronic conditions, financial burden and pharmaceutical pricing: insights from Australian consumers. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(5):589–95.

de Crespigny C, Grbich C, Watson J. Older aboriginal Women's experiences of medications in urban South Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 1998;4(4):6–17.

Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Cheetham C, Thomas T, Smith J, et al. Build it and they will come: outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an aboriginal medical service. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(1):79–82.

KPMG. National monitoring and evaluation of the indigenous chronic disease package:first monitoring report 2010–11. Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra; 2013.

Kelaher M, Taylor-Thompson D, Harrison N, O'Donoghue L, Dunt D, Barnes T, et al. Evaluation of PBS Medicine Supply Arrangements for Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services Under SECTION 100 of the National Health Act. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health, Menzies School of Health Research and the Program Evaluation Unit, University of Melbourne, 2004.

Dussart F. "It is hard to be sick now": diabetes and the reconstruction of indigenous sociality. Anthropologica. 2010;52:77–87.

Tamwoy E, Haswell-Elkins M, Wong M, Rogers W, d'Abbs P, McDermott R. Living and coping with diabetes in the Torres Strait and northern peninsula area. Health Promot J Austr. 2004;15(3):231–6.

Wong M, Haswell-Elkins M, Tamwoy E, McDermott R, d'Abbs P. Perspectives on clinic attendance, medication and foot-care among people with diabetes in the Torres Strait islands and northern peninsula area. Austr. J Rural Health. 2005;13(3):172–7.

Leishman B. Indigenous community attitudes vs compliance: the big 'shame'. QPP Alive. 2000;Mar-Apr:14–5.

Morton AP. Characteristics and outcome of type 2 diabetes in urban aboriginal people [3]. Intern Med J. 2007;37(8):581–2.

Thompson SC, Bonar M, Greville H, Bessarab D, Gilles MT, D'Antoine H, et al. "Slowed right down": insights into the use of alcohol from research with aboriginal Australians living with HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):101–10.

Bailie R, Griffin J, Kelaher M, McNeair T, Percival N, Laycock A, et al. Sentinel sites evaluation: final report. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra; 2013.

Katzenellenbogen J, Haynes E, Woods J, Bessarab D, Durey A, Dimer L, et al. Information for action: improving the heart health story for aboriginal people in Western Australia (BAHHWA report). Perth: Western Australian Centre for Rural Health, University of Western Australia; 2015.

Larkin C, Murray R. Assisting aboriginal patients with medication management. Aust Prescr. 2005;28(5):123–5+31.

Grace J, Chenhall RA. Rapid anthropological assessment of tuberculosis in a remote aboriginal community in northern Australia. Hum Organ. 2006;65(4):387–99.

Lucas R. Compliance issues in Central Australia. Central Australian rural practitioners association. Newsletter. 1997;25:14–8.

Hayman N. Medical and clinical issues for indigenous men. Aborig Isl Health Work J. 2000;24(1):4–6.

Hoy WE, Davey RL, Sharma S, Hoy PW, Smith JM, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S. Chronic disease profiles in remote Aboriginal settings and implications for health services planning. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34:11+.

DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200–9.

Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen OV, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269–86.

Truelove M, Patel A, Bompoint S, Brown A, Cass A, Hillis GS, et al. The effect of a cardiovascular polypill strategy on pill burden. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33(6):347–52.

Patel A, Cass A, Peiris D, Usherwood T, Brown A, Jan S, et al. A pragmatic randomized trial of a polypill-based strategy to improve use of indicated preventive treatments in people at high cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(7):920–30.

Selak V, Elley CR, Bullen C, Crengle S, Wadham A, Rafter N, et al. Effect of fixed dose combination treatment on adherence and risk factor control among patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ. 2014;348:g3318.

Kemp K, Nienhuys T, Boswell J, Leach A, Kantilla C, Tipuamantamirri M, et al. Strategies for and problems associated with maximising and monitoring compliance with antibiotic treatment for otitis media with effusion in a remote aboriginal community. Austr. J Rural Health. 1994;2(4):25–32.

Kruske SG, Ruben AR, Brewster DR. An iron treatment trial in an aboriginal community: improving non-adherence. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(2):153–8.

Merianos A, Gilles M, Chuah J. Ceftriaxone in the treatment of chronic donovanosis in central Australia. Genitourin Med. 1994;70(2):84–9.

Topp L, Day CA, Wand H, Deacon RM, van Beek I, Haber PS, et al. A randomised controlled trial of financial incentives to increase hepatitis B vaccination completion among people who inject drugs in Australia. Prev Med. 2013;57(4):297–303.

Ralph AP, Read C, Johnston V, de Dassel JL, Bycroft K, Mitchell A, et al. Improving delivery of secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic heart disease in remote indigenous communities: study protocol for a stepped-wedge randomised trial. Trials. 2016;17:51.

Laba TL, Lehnbom E, Brien JA, Jan S. Understanding if, how and why non-adherent decisions are made in an Australian community sample: a key to sustaining medication adherence in chronic disease? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(2):154–62.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Strengthening cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples - A guide for health professionals. Canberra: Australian Government, 2005.

Australian Health Minister's Advisory Council. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2014 report. Canberra: AHMAC, 2015.

Shahid S, Durey A, Bessarab D, Aoun SM, Thompson SC. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and aboriginal patients and their families: the perspective of service providers. BMC Health Services Res. 2013;13:460.

Acknowledgements

The lead author is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award scholarship. The provider of this scholarship had no involvement in the design, conduct or analysis of this review.

APR is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship (1084656).

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JdD developed and conducted the search strategy, identified the eligible articles, extracted the data and applied the quality assessment criteria. JdD was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. AR made substantial contributions to the design of the review and the analysis and interpretation of the data. AR was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. AC made substantial contributions to the design of the review and the interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy details. Full details of the search strategy are provided. (DOC 52 kb)

Additional file 2:

Quality assessment tool. The quality assessment template including scoring instructions. (DOC 60 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table: Characteristics and findings of evaluation reports and correspondence. A summary of the relevant information extracted from evaluation reports and correspondence. (DOC 73 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Dassel, J.L., Ralph, A.P. & Cass, A. A systematic review of adherence in Indigenous Australians: an opportunity to improve chronic condition management. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 845 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2794-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2794-y