Abstract

Background

The worldwide increase in older persons demands technological solutions to combat the shortage of caregiving and to enable aging in place. Smart home health technologies (SHHTs) are promoted and implemented as a possible solution from an economic and practical perspective. However, ethical considerations are equally important and need to be investigated.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review according to the PRISMA guidelines to investigate if and how ethical questions are discussed in the field of SHHTs in caregiving for older persons.

Results

156 peer-reviewed articles published in English, German and French were retrieved and analyzed across 10 electronic databases. Using narrative analysis, 7 ethical categories were mapped: privacy, autonomy, responsibility, human vs. artificial interactions, trust, ageism and stigma, and other concerns.

Conclusion

The findings of our systematic review show the (lack of) ethical consideration when it comes to the development and implementation of SHHTs for older persons. Our analysis is useful to promote careful ethical consideration when carrying out technology development, research and deployment to care for older persons.

Registration

We registered our systematic review in the PROSPERO network under CRD42021248543.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction/background

Significant advancements in medicine, public health and technology are allowing the world population to grow increasingly older adding to the steady rise in the proportion of senior citizens (aged over 65) [1]. Because of this growth in the aging population, the demand for and financial costs of caring for older adults are both rising [2]. That older persons generally wish to age in place and receive healthcare at home [2] may mean accepting risks such as falling, a risk that increases with frailty [3]. However, many prefer accepting these risks rather than moving into long term care facilities [4,5,6].

A solution to this multi-facetted problem of ageing safely at home and receiving appropriate care, while keeping costs at bay may be the use of smart home health technologies (SHHTs). A smart home is defined by Demiris and colleagues as “ residence wired with technology features that monitor the well-being and activities of their residents to improve overall quality of life, increase independence and prevent emergencies” [7]. SHHTs then, represent a certain type of smart home technology, which include non-invasive, unobtrusive, interoperable and possibly wearable technologies that use a concept called the Internet-of-Things (IoT) [8]. These technologies could thereby remotely monitor the older resident and register any abnormal deviations in the daily habits and vital signs while sending alerts to their formal and informal caregivers when necessary. These SHHTs could permit older people (and their caregivers) to receive the necessary medical support and attention at their convenience and will, thereby allowing them to continue living independently in their home environment.

All of these functions offer benefits to older persons wishing to age at home. While focusing on practical advantages is important, an equally important question to ask is how ethical these technologies are when used in the care of older persons. Principles of biomedical ethics, such as autonomy, justice [9], privacy [10], and responsibility [11] should not only be respected by medical professionals, but by technology developers and build-into the technologies as well.

The goal of our systematic review is therefore to investigate whether and which ethical concerns are discussed in the pertinent theoretical and empirical research on SHHTs for older persons between 2000 and 2020. Different from previous literature reviews [12,13,14],, which only explored practical aspects, we explicitly examined if and how researchers treated the ethical aspects of SHHTs in their studies, adding an important, yet often overlooked aspect to the systematic literature. Moreover, we present how and which ethical concerns are discussed in the theoretical literature and which ones in empirical literature, to shed light on possible gaps regarding which and how different ethical concerns are developed. Identifying these gaps is the first important step to eventually connecting bioethical considerations to the real world, adapting policies, guidelines and technologies itself [15]. Thus, our systematic review is the first one to do so in the context of ethical issues in SHHTs used for caregiving for older persons.

Methods

Search strategy

With the guidance of an information specialist from the University of Basel, our team developed a search strategy according to the PICO principle: Population 1 (Older adults), Population 2 (Caregivers), Intervention (Smart home health technologies), and Context (Home). The outcome of ethics was intentionally omitted as we wanted to capture all relevant studies without narrowing concerns that we would classify as “ethical”. Within each category, synonyms and spelling variations for the keywords were used to include all relevant studies. We then adapted the search string by using database-specific thesaurus terms in all ten searched electronic databases: EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, SocIndex, SCOPUS, IEEE, Web of Science, Philpapers, and Philosophers Index. We limited the search to peer-reviewed papers published between January 1st, 2000 and December 31st, 2020, written in the English, French, and German languages. This time frame allowed us to map the evolution to SHHTs as a new field.

The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) The article must be an empirical or theoretical original research contribution. Hence, book chapters, conference proceedings, newspaper articles, commentary, dissertations, and thesis were excluded. Also excluded were other systematic reviews since their inclusion would duplicate findings from our individual studies. (2) When the included study was empirical, the study’s population of interest must be older persons over 65 years of age, and/or professional or informal caregivers who provide care to older persons. Informal caregivers include anyone in the community who provided support without financial compensation. Professional caregivers include nurses and related professions who receive financial compensation for their caregiving services. (3) The included study must investigate SHHTs and their use in the older persons’ place of dwelling.

Procedure

First, we carried out the systematic search across databases and removed all duplicates through EndNote (see supplementary Table 1 in appendix part 1 for a list of all included articles). One member of the research team screened all titles manually and excluded irrelevant papers. Then, two authors screened the abstracts and excluded irrelevant papers, and any disagreements were solved by a third author. She then also combined all included articles and removed further duplicates.

Final inclusion and data extraction

All included articles were searched and retrieved online (and excluded if full text was not available). Three co-authors then started data extraction, where several papers were excluded due to irrelevant content. To code the extracted data, a template was developed, which was tested in a first round of data extraction and then used in Microsoft Excel during the remaining extraction process. Study demographics and ethical considerations were recorded. Each extracting author was responsible for a portion of articles. If uncertainties or disputes occurred, they were solved by discussion. To ensure that our data extraction was not biased, 10% of the articles were reviewed independently. Upon comparing data extracted of those 10% of our overall sample, we found that items extracted reached 80% consistency.

Data synthesis

The extracted datasets were combined and ethical discussions encountered in the publications were analyzed using narrative synthesis [16]. During this stage, the authors discussed the data and recognized seven first-order ethical categories. Information within these categories were further analyzed to form sub-categories that describe and/or add further information to the key ethical category.

Results

Nature of included articles

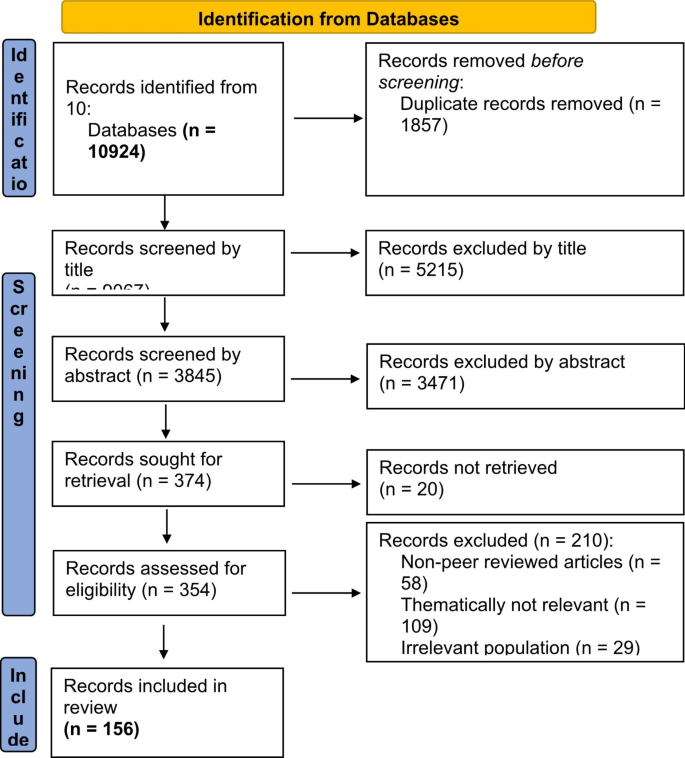

Our search initially identified 10,924 papers in ten databases. After the duplicates were removed, 9067 papers remained whose titles were screened resulting in exclusion of 5215 papers (Fig. 1). The examination of remaining 3845 abstracts of articles led to the inclusion of 374 papers for full-texts for retrieval. As we were unable to find 20 papers after several attempts, the remaining 354 full-texts were included for full-text review. In this full-text review phase, we further excluded 198 full-texts with reasons (such as technologies employed in hospitals, or technologies unrelated to health). Ultimately, this systematic review included 144 empirical and 12 theoretical papers specifying normative considerations of SHHTs in the context of caregiving for older persons.

Almost all publications (154 out of 156) were written in English, and over 67% [105] were published between 2014 and 2020. About a quarter (26%; 41 papers) were published between 2007 and 2013 and only 7% (10 articles) were from 2000 to 2006. Apart from the 12 theoretical papers, the methodology used in the 144 empirical papers included the following: 42 articles (29%) used a mixed-methods approach, 39 (27%) experimental, 38 (26%) qualitative, 15 (10%) quantitative, and the remaining were of an observational, ethnographical, case-study, or iterative testing nature.

The functions of SHHTs tested or studied in the included empirical papers were categorized as such: 29 articles (20.14%) were solely involved with (a) physiological and functioning monitoring technologies, 16 (11.11%) solely with (b) safety/security monitoring and assistance functions, 23 (15.97%) solely promoted (c) social interactions, and 9 (6.25%) solely for (d) cognitive and sensory assistance. However, 46 articles (29%) also involved technologies that fulfilled more than one of the categorized functions. The specific types of SHHTs included in this review comprised: intelligent homes (71 articles, 49.3%); assistive autonomous robots (49 articles, 34.03%); virtual/augmented/mixed reality (7, 4.4%); and AI-enabled health smart apps and wearables (4 articles, 1.39%). Likewise, the remaining 20 articles (12.8.8%) involved either multiple technologies or those that did not fall into any of the above categories.

Ethical considerations

Of the 156 papers included, 55 did not mention any ethical considerations (See supplementary Table 1 in appendix part 1). Among the 101 papers that noted one or more ethical considerations, we grouped them into 7 main categories (1) privacy, (2) human vs. artificial relationships, (3) autonomy, (4) responsibility, (5) social stigma and ageism, (6) trust, and (7) other normative issues (see Table 1). Each of these categories consists of various sub-categories that provided more information on how smart home health technologies (possibly) affected or interacted with the older persons or caregivers in the context of caregiving (Table 2). Each of the seven ethical considerations are explained in depth in the following paragraphs.

Privacy

This key category was cited across 58 articles. In theoretical articles, privacy was one of the most often discussed ethical consideration, as 9 out of 12 mentioned privacy related concerns. Among the 58 articles, four sub-issues within privacy were discussed.

(A)The awareness of privacy was reported as varying according to the type of SHHT end-user. Whereas some end-users were more aware or privacy in relation to SHHTs, others denoted little or a total lack of consideration, while some had differing levels of concerns for privacy that changed as it is weighed against other values, such as access to healthcare [17] or feeling of safety [18]. Both caregivers and researchers often took privacy concerns into account [19,20,21], while older persons themselves did not share the same degree of fears or concerns [22,23,24]. Older persons in fact were less concerned about privacy than costs and usability [23]. Furthermore, they were willing to trade privacy for safety and the ability to live at home. Nevertheless, several papers acknowledged that privacy is an individualized value, whereby its significance depends on both the person and their context, thus their preferences cannot be generalized [25,26,27,28]. Lastly, there were also some papers that explicitly stated that there were no privacy concerns found by the participants, or that participants found it useful to have monitoring without mentioning privacy as a barrier [29,30,31].

The second prevalent sub-issue within privacy was (B) privacy by choice. Both older persons and their caregivers expressed a preference for having a choice in technology used, in what data is collected, and where technology should or should not be to installed [32, 33]. For example, some spaces were perceived as more private and thus monitoring felt more intrusive [34,35,36]. Formal caregivers were concerned about monitoring technologies being used as a recording device for their work [37, 38]. Furthermore, older persons were often worried about cameras [39, 40] and “eyes watching”, even if no cameras were involved [41,42,43].

The third privacy concern was (C) risk and regulation of privacy, which included discussions surrounding dissemination of data or active data theft [44,45,46,47], as well as change in behavior or relationships due to interaction with technology [48, 49]. Researchers were aware of both legal and design-contextual measures that must be observed in order to ensure that these risks were minimized [45, 50, 51].

The final sub-issue that we categorized was (D) privacy in the case of cognitive impairment. This included disagreements if cognitive impairment warrants more intrusive measures or if privacy should be protected for everyone in the same way [52, 53].

Human versus artificial relationships

54 articles in our review contained data pertinent to trade-offs between human and artificial caregiving. Firstly, (A) there was a general fear that robots would replace humans in providing care for older persons [28, 54,55,56], along with related concerns such as losing jobs [40, 57], disadvantages with substituting real interpersonal contact [17, 46], and thus increasing the negative effects associated with social isolation [41, 58].

Many papers also emphasized (B) the importance of human caregiving, underlining the necessity of human touch [26, 47, 50, 59] believing that technology should and could not replace humans in connections [17], love [33], relationships [60], and care through attention to subtle signs of health decline in every in-person visit [57]. Older persons also preferred human contact over machines and had guarded reactions to purely virtual relationships[31, 61, 62]. The use of technology was seen to dehumanize care, as care should be inherently human-oriented [27, 48].

There was data alluding to (C) the positive reactions to technologies performing caregiving tasks and possibly forming attachments with the technology[47, 49, 58]. Furthermore, some papers cited participants reacting positively to robots replacing human care, where the concept of “good care” could be redefined [63,64,65,66]. Solely theoretical papers also identified possible benefits of tech for socialization and relationship building [67, 68].

Finally, many articles raised the idea of (D) collaboration between machine and human to provide caregiving to older persons [69]. These studies highlighted the possible harms if such collaboration was not achieved, such as informal caregivers withdrawing from care responsibilities [70] or the reinforcement of oppressive care relations [71]. Interestingly, opinions varied on whether the caregiving technology, such as a robot should have “life-like” appearance, voices, and emotional expressions, while recognizing the current technological limits in actually providing those features to a satisfactory level [46]. For example, some users preferred for the robot to communicate with voice commands, while others wanted to further customize this function with specific requests on the types of voices generated [65, 72].

Autonomy

40 papers mentioned autonomy of the older person with respect to the use of SHHTs. The first sub-theme categorized was in relation to (A) control, which encompassed positive aspects like (possible) empowerment through technology [25, 26, 73, 74] and negative aspects such as the possibility of technology taking control over the older person, thus increasing dependence [55, 75] or decreasing freedom of decision making [48]. Several studies reported the wishes of older persons to be in control when using the technology (e.g. technology should be easily switched off or on) and be in control of its potential, meaning the extend of data collected or transferred, for example [17, 30, 70, 76]. Furthermore, they should have the option to not use technology in spaces where they do not wish to, e.g., public spaces [35]. The issue of increased dependency was discussed as a loss or rather, fear of the loss of autonomy due to greater reliance on technology as well as the fear of being monitored all the time [28, 48]. In addition, using technology was deemed to make older persons more dependent and to increase isolation [77].

The second sub-category within autonomy highlighted the need for the technology to (B) protect the autonomy and dignity of its older end-users, which also included the unethical practice of deception (e.g.[46, 49, 54, 78], infantilization [31, 60], or paternalism [17, 27, 57], as a way to disrespect older persons’ dignity and autonomy [79,80,81]. Also reported was that these users may accept technology to avoid being a burden on others, thus underscoring the value of technology to enhance functional autonomy, understood here as independent functioning [52, 82, 83]. Other studies mentioned this kind of trade-off between autonomy and other values or interests as well. For example, between respecting the autonomy of the older persons versus nudging them towards certain behavior (perceived as beneficial for them) through the help of technology [32], or between autonomy and safety [24].

Two sub-issues within autonomy primarily discussed in the theoretical publications were (C) relational autonomy [27, 41, 49, 58] and (D) explanations on why autonomy should actually be preserved. The former emphasized the fact that older persons do not and should not live isolated lives and that there should be respect and promotion of their relationships with family members, friends, caregivers, and the community as a whole [27, 47]. The latter described the benefits of respecting autonomy, such as increased happiness and well-being [65, 67] or a sense of purpose [84], and thus favoring the promotion of autonomy and choice also from a normative perspective.

Responsibility

This theme included data across 25 articles that mentioned concerns such as the effect of using technologies on the current responsibilities of caregivers and older persons themselves. Specifically, the papers discussed (A) the downsides of assistive home technology on responsibility. That is, the use of technology conflicted with moral ideas around responsibility [58], especially for caregivers [57, 59]. Its use also raised more practical concerns, such as the fear of shifting the responsibility onto the technology and thus, diminishing vigilance and/or care. Related to this thought was also a fear of increased responsibility on both older persons [60] and their caregivers, who were worried about extra work time was needed to integrate technology into their work, learn its functions, analyze data, and respond to potentially higher frequencies of alerts [18, 35, 36, 53, 85].

Additionally, studies reported (B) continuous negotiation between (formal) caregivers’ (professional) responsibilities of care and the opportunities that smart technologies could provide [26, 47, 55, 70, 82]. For example, increased need for cooperation between informal and formal caregivers due to technology was foreseen [81] and fear expressed that over-reliance on female caregivers was exacerbated [71]. Nevertheless, the use of smart home health technologies was often seen to (C) reduce the burden of care, where caregivers could direct their attention and time to the most-needed situations and better align the responsibilities of care [5, 18, 49, 74, 80, 81]. This shift of burden onto a technology was also reported by older persons as freeing [48].

Ageism and stigma

24 articles discussed ageism and stigma, which included discussions about fear of (A) being stigmatized by others with the use of SHHTs [73, 86]. Older persons thought acceptance of such technologies also alluded to an admission of failure [82], or being perceived by others as frail, old, forgetful [77, 87], or even stupid [26, 33, 88]. This resulted in them expressing ageist views stating that they did not need the technology “yet” [84, 89]. Some papers reported the belief that the presence of robots was disrespectful for older people [52, 85, 90] and technologies do little to alleviate frustration and the impression of “being stupid” that older persons may have when they are faced with the complexities of the healthcare system [73]. Furthermore, older persons in a few studies did express unfamiliarity with learning new technologies in old age [42, 66, 91], coupled with fears of falling behind and not keeping up with their development, and feeling pressured to use technology [62, 89].

Within ageism and stigma, (B) social influence was deemed to cause older persons to believe that the longer they have been using technology, the more their loved ones want them to use it as well, creating a sort of reinforcing loop [27]. Other social points were related to self-esteem, meaning that older persons needed to reach a certain threshold first to publicly admit that they need technology [85], or doubts by caregivers if they were able to use the devices [36]. This possibly led older persons to prefer unobtrusive technology and those that could not be noticed by visitors [22, 55, 88].

Lastly, (C) two theoretical articles raised concerns in regard to technology exacerbating stigmatization of women and migrants in caregiving. Both Parks [47] and Roberts & Mort [71] suggested that caregiving technology which does not question the underlying expectation that women give care to their relatives will worsen such gendered expectations in caregiving.

Trust

We identified 18 articles that mentioned some aspect of trust. For both older persons and caregivers, there was often (A) a general mistrust with technologies compared with existing human caregiving [33, 42]. Therefore, caregivers became proxies and were relied on to “understand it” and continue providing care [48]. For caregivers the lack of trust was associated with the use of technologies, for example, leaving older persons alone with technology [81], worrying that older persons would not trust the technology [29, 32] or that it could change their professional role [23]. One paper even reported that using technology meant caregivers themselves are not trusted [92]. Surprisingly, some studies found that older persons had no problem trusting technology, even considering it safer and more reliable than humans [58, 70].

The second sub-theme concerned (B) characteristics promoting trust. That is, the degree of automation [30](, the involvement of trusted humans in design and use [34, 93], perceived usefulness of the technology and spent time with the technology all influenced trust [59, 72, 94]. For robots specifically, they were trusted more than virtual agents, such as Alexa [60, 65]. Taking this step further, studies discovered that robots with a higher degree of automation or a lower degree in anthropomorphism level increased trust [30].

Other

There were several miscellaneous considerations not fitting the ones already mentioned above, and we categorized them as follows. Firstly, two theoretical articles mentioned (A) considerations related to research. Ho, [27] pointed out that empirical evidence of the usefulness of SHHTs is lacking, which therefore may make them less relevant as a possible solution for aging in place. Palm et al. (2013) suggested that, if research would consider the fact that many costs of caregiving are hidden because of non-paid informal caregivers, the actual economic benefits of SHHTs are unknown. Lastly, two articles alluded to (B) psychological phenomena related to the use of SHHTs. Pirhonen et al., [58] suggested that robots can promote the ethical value of well-being through the promotion of feelings of hope. The other phenomenon was feeling of blame and fear associated with the adoption of the technology, as caregivers may be pushed to use SHHTs in order to not be blamed for failing to use technology [18]. This then also nudged caregivers to think that using SHHTs cannot do any harm, so it is better to use it than not use it.

Discussion

Our systematic review investigated if and how ethical considerations appear in the current research on SHHTs in the context of caregiving for older persons. As we included both empirical and theoretical works of literature, our review is more comprehensive that existing systematic reviews (e.g.[12,13,14], that have either only explored the empirical side of the research and neglected to study ethical concerns. Our review offers an informative and useful insights on dominant ethical issues related to caregiving, such as autonomy and trust [95, 96]. At the same time, the study findings brings forth less known ethical concerns that arise when using technologies in the caregiving context, such as responsibility [97] and ageism and stigma.

The first key finding of our systematic review is the silence on ethics in SHHTs research for caregiving purposes. Over a third of the reviewed publications did not mention any ethical concern. One possible explanation is related to scarcity [98]. In the context of research in caregiving for older persons, “scarcity” can be understood in a variety of ways: one way is to see the available space for ethical principles in medical technology research as scarce. For example, according to Einav & Ranzani [99] “Medical technology itself is not required to be ethical; the ethics of medical technology revolves around when, how and on whom each technology is used” (p.1612). Determining the answers to these questions is done empirically, by providing proof of benefit of the technology, ongoing reporting on (possibly harmful) long term effects, and so on [99]. Given that publication space in journal is limited to a certain amount of text, the available space that ethical considerations can take up is scarce. Therefore, adding deliberations about the unearthed values or issues in our systematic review, like trust, responsibility or ageism, may simply not fit in the space available in research publications. This may also be the reason why the values of beneficence and non-maleficence were not found through our narrative analysis. While both values are considered crucial in biomedical ethics [9], the empirically measured benefits may be considered enough by the authors to demonstrate beneficence (and non-maleficence), leading them to not mention the ethical values explicitly again in their publications.

Another interpretation is the scarcity of time, and the felt pressure to “solve” the problem of limited resources in caregiving [2]. Researchers might be therefore more inclined to focus on the empirical data showing benefits, rather than to engage in elaborations on ethical issues that arise with those benefits. Lastly, as researchers have to compete for limited funding [100] and given that technological research receives more funding than biomedical ethics [101], it is likely that the numbers of publications mentioning purely empirical studies exceeds those publications that solely mention the ethical issues (as our theoretical papers did) or that combine empirical and ethical parts. Further research needs to investigate these hypotheses further.

It is not surprising that privacy was the most discussed ethical issue in relation to SHHTs in caregiving. The topic of privacy, especially in relation to monitoring technologies and/or health, has been widely discussed (see for example [102,103,104]. A particularly interesting finding within this ethical concern was related to privacy and cognitive impairment. While discussions around autonomy and cognitive impairment are popular in bioethical research (see e.g. [105, 106], privacy, on the other hand, has recently gained more attention for both researchers and designers [107]. The relation in the reviewed studies between cognitive impairment and privacy seemed to be reversely correlated –intrusions into the privacy of older persons with cognitive impairments were deemed as more justified [35, 53], which necessarily does not mean that its ethical, but a practical fact that such intrusions become possible or necessary in the given context. A possible explanation lies in the connectedness of autonomy and privacy, in the sense that autonomy is needed to consent for any sort of intrusions [108].

Surprisingly, more research papers mentioned the topic of human vs. artificial relationships as an ethical concern than autonomy. Autonomy is often the most discussed ethics topic when it comes to use of technology [96]. However, fears associated with technology replacing human care has recently gained traction [109,110,111].The significance of this theme is likely due to the fact that caregiving for older persons has been (and is) a very human-centric activity [112]. As mentioned before, the persons willing and able to do this labor (both paid and unpaid caregiver) are limited and their pool is shrinking [113]. The idea of technology possibly filling this gap is not new [114], but is also clearly causing wariness among both older persons and caregivers, as we have discovered [56, 61]. Frequently mentioned was the fear of care being replaced by technology. This finding was to be expected, as nursing is not the only profession where introduction of technology caused fears of job loss [115]. Within this ethical concern, the importance of human touch and human interaction was underlined [110, 111]. Human touch is an important asset for caregivers when they care for older patients, particularly those with dementia, as it is one of the few ways to establish connection and to calm the patient with dementia [116]. Similarly, human touch and face-to-face interactions are mentioned as a critical aspect of caregiving in general, both for the care recipient and the caregiver [117, 118]. While caregivers see the aspect of touching and interacting with older care recipients as a way to make their actions more meaningful and healing [90, 117], for care recipients being touched, talked and listened to is part of feeling respected and experiencing dignity [118, 119]. Introducing technology into the caregiving profession may therefore quickly elicit associations with cold and lifeless objects [59]. Future developments, both in the design of the technologies themselves and their implementation in caregiving will require critical discussion among concerned stakeholders and careful decision on how and to what extent the human touch and human care must be preserved.

A unique ethical concern that we have not seen in previous research [120, 121] is responsibility, and remarkable within this concern was SHHTs’ negative impact on it. As previously mentioned, the human being and human interaction are seen as central to caregiving [117, 118]. This can possibly be extended to concepts exclusively attributable to humans, such as the concept of moral responsibility [122]. Shifting caregiving tasks onto a technological device, which, by being a device and not a human carer, cannot be morally responsible in the same way as a human being can [123], may introduce a sense of void that caregivers are reluctant to create. Studies have shown that a mismatch in professional and personal values in nursing causes emotional discomfort and stress [124], therefore the shift in the professional environment caused by SHHTs is likely to be met with aversion. Additionally, the negative impact of SHHTs on caregiving responsibility was also tied to practical concerns, like not having enough time to learn how to use the technology by the caregivers [35], or needing to have access to and checking the older person’s health data [36]. Such concerns point to the possibility that SHHTs can create unforeseen tasks, which could turn into true burdens, instead of alleviating caregivers. Indeed, there are indications that the increase in information about the older person through monitoring technologies causes stress for both caregivers and older persons, as the former feel pressure to look at the available data, while the latter prefer to hide unfavorable information to not seem burdensome for their caregivers [125]. Another consequence of SHHTs that emerged as a sub-category was the renegotiation of responsibilities among the different stakeholders. In the field of (assistive) technology, this renegotiation is an ongoing process with efforts to make technology and its developers more accountable, through new policies and regulations [126]. In the realm of assistive technology in healthcare, these negotiations focus on high-risk cases and emergencies [127]. Who is responsible for the death of a person if the assistive technology failed to recognize an emergency, or to alert humans in time? Such issues around responsibility and legal liability are partially responsible for the slow uptake of technology in caregiving [128].

Another important but less discussed ethical concern was ageism and stigma. Ageist prejudices include being perceived as slow, useless, burdensome, and incompetent [129]. Fear of aging and becoming a burden to others is a fear many older persons have, as current social norms demand independence until death [130]. Furthermore, the general ubiquitous use of technology has possibly exacerbated the issue of ageism, as life became fast paced and more pressure is placed on aging persons to keep up [131]. While this would call for more attention to studying ageism in relation to technology, our findings indicate that, it does not unfortunately seem at the forefront of concerns that are prevalent in the literature (and thereby the society).

Related to ageism, is the wish of older persons to not be perceived as old and/or in the need of assistance (in the form of technology) explains the prevalent demand for unobtrusive technology. Obtrusiveness, in the context of SHHTs, is defined as “undesirably prominent and or/noticeable”, yet this definition should include the user’s perception and environment, and is thus not an objectively applicable definition [132]. Nevertheless, we can infer that by “unobtrusive”, users mean SHHTs that is not noticeable by them or, mostly importantly, by other persons to possibly reduce stigma associated with using a technology deemed to be for persons with certain limitations. Further research will have to confirm if unobtrusive technology actually reduces stigma and/or fosters acceptance of such SHHTs in caregiving.

Lastly, the sub-theme of stigmatization of women and immigrants in caregiving and possibly exacerbating their caregiving burden through technology was only discovered in two theoretical publications [47, 71]. While it is well known that caregiving burden mostly falls upon women [133, 134], many of them with a migration background when it comes to live-in caregivers [135, 136]. It is surprising that we found no redistribution of burden of care with technology. This is likely due to the fact that caregiving – be it technologically assisted or not – remains perceived as a more feminine and, unfortunately, low status profession [137]. The development of technology, however, are still mostly associated with masculinity This tension between the innovators and actual users of technology can lead to the exacerbation of stigma for female and migrant caregivers, as the human bias is conserved by the technology, instead of disrupted through it [137].

Finally, trust was an expected ethical concern, given that it is a widely discussed topic in relation to technology (see for example, [123, 138] and also in the context of nursing [95, 139]. Older persons were trusting caregivers to understand SHHTs [48], while caregivers feared that older persons would not trust the used technology, even though said persons did not express such concerns [32]. A possibility to mitigate such misunderstandings and put both caregivers and care recipients on an equal understanding of the technology are education tools [140]. Another surprising finding was that some older persons were inclined to trust SHHTs even more than human caregivers, as they were seen as more reliable [70]. This trust in technology was increased when a physical robot instead of an only virtual agent was involved [60, 65]. Studies in the realm of embodiment of virtual agents and robots suggest that the presence of a body or face promotes human-like interactions with said agents [51]. Furthermore, our systematic review discovered other characteristics which promote trust in SHHTs, such as perceived usefulness [94] or time spent with the technology [59]. Another important aspect is the already existing trust in the person introducing the technology to the user [34, 93]. In combining these characteristics in the design and implementation of SHHTs in caregiving, researchers and technology developers need to find creative mechanisms to facilitate trustworthiness and foster adoption of new technologies in caregiving.

Limitations

While we searched 10 databases for publications over a span of 20 years, we are aware that older or newer publications will have escaped our systematic review. Relevant new literature that we have found when writing our results have been incorporated in this manuscript. Furthermore, as we specifically refrained from using terms related to ethics in our search strings to also capture the instances of absence of ethical concerns, this choice may have led to missing a few articles as a consequence, especially in regards to theoretical publications. Lastly, due to lack of resources, we were unable to carry out independent data extraction for all included papers (N = 156) and chose to validate the quality of extracted data by using a random selection of 10% of the included sample. Since there was high agreement on extracted data, we are confident about the quality of our study findings.

Conclusion

SHHTs offer the possibility to mitigate the shortage of human caregiving resources and to enable older persons to age in place, being adequately supported by technology. However, this shift in caregiving comes with ethical challenges. If and how these ethical challenges are mentioned in the current research around SHHTs in caregiving for older persons was the goal of this systematic review. Through analyzing 156 articles, both empirical and theoretical, we discovered that, while over one third of articles did not mention any ethical concerns whatsoever, the other two thirds discussed a plethora of ethical issues. Specifically, we discovered the emergence of concerns with the use of technology in the care of older persons around the theme of human vs. artificial relationships, ageism and stigma, and responsibility. In short, our systematic review offers a comprehensive overview of the currently discussed ethical issues in the context of SHHTs in caregiving for older persons. However, scholars in the fields of gerontology, ethics, and technology working on such issues would be already (or should be) aware that ethical concerns will change with each developing technology and the population it is used for. For instance, with the rise of Artificial intelligence/Machine Learning, new intelligent or smart technologies will continue to mature with use and time. Thus, ethical value such as autonomy will require re-evaluation with this significant content development as well as deciding, if the person would/should be asked to re-consent or how should this decision making proceed should he or she have developed dementia. In sum, more critical work is necessary to prospectively act on ethical concerns that may arise with new and developing technologies that could be used in reducing caregiving burden now and in the future.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this systematic review are included in this published article and its appendices. Appendix part 1 contains all included articles and their characteristics. Appendix part 2 contains the search strategy and all search strings for all searched databases, as well as the PROSPERO registration number.

References

Hertog S, Cohen B, Population. 2030: Demographic challenges and opportunities for sustainable development planning. undefined [Internet]. 2015 [zitiert 11. Juli 2022]; Verfügbar unter: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Population-2030%3A-Demographic-challenges-and-for-Hertog-Cohen/f0c5c06b4bf7b53f7cb61fe155e762ec23edbc0b

Bosch-Farré C, Malagón-Aguilera MC, Ballester-Ferrando D, Bertran-Noguer C, Bonmatí-Tomàs A, Gelabert-Vilella S. u. a. healthy ageing in place: enablers and barriers from the perspective of the elderly. A qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–23.

Cuvillier B, Chaumon M, Body S, Cros F. Detecting falls at home: user-centered design of a pervasive technology. Hum Technol November. 2016;12(2):165–92.

Fitzpatrick JM, Tzouvara V. Facilitators and inhibitors of transition for older people who have relocated to a long-term care facility: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community Mai. 2019;27(3):e57–81.

Lee DTF, Woo J, Mackenzie AE. A review of older people’s experiences with residential care placement. J Adv Nurs Januar. 2002;37(1):19–27.

Rohrmann S. Epidemiology of Frailty in Older People. In: Veronese N, Herausgeber. Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases: Research into an Elderly Population [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [zitiert 10. Februar 2022]. S. 21–7. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology). Verfügbar unter: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_3

Demiris G, Hensel BK, Skubic M, Rantz M. Senior residents’ perceived need of and preferences for “smart home” sensor technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care Januar. 2008;24(01):120–4.

Majumder S, Aghayi E, Noferesti M, Memarzadeh-Tehran H, Mondal T, Pang Z. u. a. Smart Homes for Elderly Healthcare-Recent advances and Research Challenges. Sens 31 Oktober. 2017;17(11):E2496.

Holm S. Autonomy, authenticity, or best interest: everyday decision-making and persons with dementia. Med Health Care Philos 1 Mai. 2001;4(2):153–9.

Trothen TJ. Intelligent Assistive Technology Ethics for Aging Adults: Spiritual Impacts as a Necessary Consideration | EndNote Click [Internet]. 2022 [zitiert 12. Juli 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://click.endnote.com/viewer?doi=10.3390%2Frel13050452&token=WzMxNTc3MzUsIjEwLjMzOTAvcmVsMTMwNTA0NTIiXQ.zGm-wqWo8mCI5L8GIchNEsUCQjg

Cook AM. Ethical issues related to the Use/Non-Use of Assistive Technologies. Dev Disabil Bull. 2009;37:127–52.

Demiris G, Hensel BK. Technologies for an aging society: a systematic review of „smart home“ applications.Yearb Med Inform. 2008;33–40.

Liu L, Stroulia E, Nikolaidis I, Miguel-Cruz A, Rios Rincon A. Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: a systematic review. Int J Med Inf Juli. 2016;91:44–59.

Moraitou M, Pateli A, Fotiou S. Smart Health Caring Home: a systematic review of Smart Home Care for Elders and Chronic Disease Patients. In: Vlamos P, editor. Herausgeber. GeNeDis 2016. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. pp. 255–64. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology).

Klingler C, Silva DS, Schuermann C, Reis AA, Saxena A, Strech D. Ethical issues in public health surveillance: a systematic qualitative review. BMC Public Health 4 April. 2017;17(1):295.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rogers M. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1 | Semantic Scholar [Internet]. 2006 [zitiert 15. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Guidance-on-the-conduct-of-narrative-synthesis-in-A-Popay-Roberts/ed8b23836338f6fdea0cc55e161b0fc5805f9e27

Draper H, Sorell T. Ethical values and social care robots for older people: an international qualitative study. Ethics Inf Technol 1 März. 2017;19(1):49–68.

Hall A, Wilson CB, Stanmore E, Todd C. Implementing monitoring technologies in care homes for people with dementia: a qualitative exploration using normalization process theory. Int J Nurs Stud Juli. 2017;72:60–70.

Airola E, Rasi P. [PDF] Domestication of a Robotic Medication-Dispensing Service Among Older People in Finnish Lapland | Semantic Scholar [Internet]. 2020 [zitiert 6. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Domestication-of-a-Robotic-Medication-Dispensing-in-Airola-Rasi/c8a84330af2410efdc0c6efcf56fbaf3490a8292

Aloulou H, Mokhtari M, Tiberghien T, Biswas J, Phua C, Kenneth Lin. JH, u. a. Deployment of assistive living technology in a nursing home environment: methods and lessons learned. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 8 April. 2013;13:42.

Bankole A, Anderson M, Homdee N. BESI: Behavioral and Environmental Sensing and Intervention for Dementia Caregiver Empowerment—Phases 1 and 2 [Internet]. 2020 [zitiert 6. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1533317520906686

Alexander GL, Rantz M, Skubic M, Aud MA, Wakefield B, Florea E. u. a. sensor systems for monitoring functional status in assisted living facility residents. Res Gerontol Nurs Oktober. 2008;1(4):238–44.

Cavallo F, Aquilano M, Arvati M. An ambient assisted living approach in designing domiciliary services combined with innovative technologies for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a case study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen Februar. 2015;30(1):69–77.

Hunter I, Elers P, Lockhart C, Guesgen H, Singh A, Whiddett D. Issues Associated With the Management and Governance of Sensor Data and Information to Assist Aging in Place: Focus Group Study With Health Care Professionals. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2. Dezember 2020;8(12):e24157.

Cahill J, Portales R, McLoughin S, Nagan N, Henrichs B, Wetherall S. IoT/Sensor-Based infrastructures promoting a sense of Home, Independent Living, Comfort and Wellness. Sens 24 Januar. 2019;19(3):485.

Demiris G, Hensel B. Smart Homes” for patients at the end of life. J Hous Elder 20 Februar. 2009;23(1–2):106–15.

Ho A. Are we ready for artificial intelligence health monitoring in elder care? BMC Geriatr Dezember. 2020;20(1):358.

Kang HG, Mahoney DF, Hoenig H, Hirth VA, Bonato P. Hajjar I, u. a. In situ monitoring of Health in older adults: Technologies and Issues: ISSUES IN IN SITU GERIATRIC HEALTH MONITORING. J Am Geriatr Soc August. 2010;58(8):1579–86.

Arthanat S, Begum M, Gu T, LaRoche DP, Xu D, Zhang N. Caregiver perspectives on a smart home-based socially assistive robot for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2 Oktober. 2020;15(7):789–98.

Erebak S, Turgut T. Caregivers’ attitudes toward potential robot coworkers in elder care. Cogn Technol Work Mai. 2019;21(2):327–36.

Meiland FJM, Hattink BJJ, Overmars-Marx T, de Boer ME, Jedlitschka A, Ebben PWG. u. a. participation of end users in the design of assistive technology for people with mild to severe cognitive problems; the european Rosetta project. Int Psychogeriatr Mai. 2014;26(5):769–79.

Bedaf S, Marti P, De Witte L. What are the preferred characteristics of a service robot for the elderly? A multi-country focus group study with older adults and caregivers. Assist Technol 27 Mai. 2019;31(3):147–57.

Epstein I, Aligato A, Krimmel T, Mihailidis A. Older adults’ and caregivers’ perspectives on In-Home Monitoring Technology. J Gerontol Nurs 15 März. 2016;42:1–8.

Chung J, Demiris G, Thompson HJ, Chen KY, Burr R, Patel S. u. a. feasibility testing of a home-based sensor system to monitor mobility and daily activities in korean American older adults. Int J Older People Nurs. 2017;12(1):e12127.

Niemelä M, van Aerschot L, Tammela A, Aaltonen I, Lammi H. Towards ethical guidelines of using Telepresence Robots in Residential Care. Int J Soc Robot 1 Juni. 2019;13(3):431–9.

Robinson EL, Park G, Lane K, Skubic M, Rantz M. Technology for healthy independent living: creating a tailored In-Home Sensor System for older adults and family caregivers. J Gerontol Nurs Juli. 2020;46(7):35–40.

Barnier F, Chekkar R. Building automation, an acceptable solution to dependence? Responses through an Acceptability Survey about a Sensors platform. IRBM Juni. 2018;39(3):167–79.

Birks M, Bodak M, Barlas J, Harwood J, Pether M. Robotic Seals as Therapeutic Tools in an aged care facility: a qualitative study. J Aging Res 1 Januar. 2016;2016:1–7.

Bertera E, Tran B, Wuertz E, Bonner A. A study of the receptivity to telecare technology in a community-based elderly minority population. J Telemed Telecare 1 Februar. 2007;13:327–32.

Mahoney D. An evidence-based adoption of Technology Model for Remote Monitoring of Elders’ Daily Activities. Ageing Int 1 September. 2010;36:66–81.

Boissy P, Corriveau H, Michaud F, Labonte D, Royer MP. A qualitative study of in-home robotic telepresence for home care of community-living elderly subjects. J Telemed Telecare 1 Februar. 2007;13:79–84.

Bradford DK, Kasteren YV, Zhang Q, Karunanithi M. Watching over me: positive, negative and neutral perceptions of in-home monitoring held by independent-living older residents in an australian pilot study. Ageing Soc Juli. 2018;38(7):1377–98.

Cohen C, Kampel T, Verloo H. Acceptability Among Community Healthcare Nurses of Intelligent Wireless Sensor-system Technology for the Rapid Detection of Health Issues in Home-dwelling Older Adults. Open Nurs J [Internet]. 17. April 2017 [zitiert 6. September 2022];11(1). Verfügbar unter: https://opennursingjournal.com/VOLUME/11/PAGE/54/

Boise L, Wild K, Mattek N, Ruhl M, Dodge HH, Kaye J. Willingness of older adults to share data and privacy concerns after exposure to unobtrusive in-home monitoring. Gerontechnology 22 Januar. 2013;11(3):428–35.

Li CZ, Borycki EM. Smart Homes for Healthcare. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;257:283–7.

Moyle W. The promise of technology in the future of dementia care. Nat Rev Neurol Juni. 2019;15(6):353–9.

Parks JA. Home-Based Care, Technology, and the maintenance of selves. HEC Forum Juni. 2015;27(2):127–41.

Essén A. The two facets of electronic care surveillance: An exploration of the views of older people who live with monitoring devices | Request PDF [Internet]. 2008 [zitiert 6. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5457066_The_two_facets_of_electronic_care_surveillance_An_exploration_of_the_views_of_older_people_who_live_with_monitoring_devices

Preuß D, Legal F. Living with the animals: animal or robotic companions for the elderly in smart homes? J Med Ethics Juni. 2017;43(6):407–10.

Geier J, Mauch M, Patsch M, Paulicke D. Wie Pflegekräfte im ambulanten Bereich den Einsatz von Telepräsenzsystemen einschätzen - eine qualitative studie. Pflege Februar. 2020;33(1):43–51.

Kim JY, Liu N, Tan HX, Chu CH. Unobtrusive monitoring to Detect Depression for Elderly with Chronic Illnesses. IEEE Sens J September. 2017;17(17):5694–704.

Barrett E, Burke M, Whelan S, Santorelli A, Oliveira BL, Cavallo F. u. a. evaluation of a companion robot for individuals with dementia: quantitative findings of the MARIO project in an irish residential care setting. J Gerontol Nurs 1 Januar. 2019;47(7):36–45.

Kinney JM, Kart CS, Murdoch LD, Conley CJ. Striving to provide Safety assistance for families of Elders: the SAFE House Project. Dement 1 Oktober. 2004;3(3):351–70.

Baisch S, Kolling T, Rühl S, Klein B, Pantel J, Oswald F. Emotionale Roboter im Pflegekontext: Empirische Analyse des bisherigen Einsatzes und der Wirkungen von Paro und Pleo. Z Für Gerontol Geriatr. Januar 2018;51(1):16–24.

Bobillier Chaumon ME, Cuvillier B, Body Bekkadja S, Cros F. Detecting falls at home: user-centered design of a Pervasive Technology. Hum Technol 29 November. 2016;12:165–92.

Lussier M, Couture M, Moreau M, Laliberté C, Giroux S, Pigot H. u. a. integrating an ambient assisted living monitoring system into clinical decision-making in home care: an embedded case study. Gerontechnology 15 März. 2020;19:77–92.

Klein B, Schlömer I. A robotic shower system: Acceptance and ethical issues. Z Gerontol Geriatr Januar. 2018;51(1):25–31.

Pirhonen J, Melkas H, Laitinen A, Pekkarinen S. Could robots strengthen the sense of autonomy of older people residing in assisted living facilities?—A future-oriented study. Ethics Inf Technol Juni. 2020;22(2):151–62.

Kleiven HH, Ljunggren B, Solbjør M. Health professionals’ experiences with the implementation of a digital medication dispenser in home care services - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 16 April. 2020;20(1):320.

Görer B, Salah AA, Akın HL. An autonomous robotic exercise tutor for elderly people. Auton Robots 1 März. 2017;41(3):657–78.

Berridge C, Chan KT, Choi Y. Sensor-Based Passive Remote Monitoring and Discordant Values: Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Low-Income Immigrant Elders in the United States. JMIR MHealth UHealth.25. März 2019;7(3):e11516.

Frennert S, Forsberg A, Östlund B. Elderly People’s Perceptions of a Telehealthcare System: Relative Advantage, Compatibility, Complexity and Observability.J Technol Hum Serv. 1. Juli2013;31.

Huisman C, Kort H. Two-year use of Care Robot Zora in dutch nursing Homes: an evaluation study. Healthc Basel Switz 19 Februar. 2019;7(1):E31.

Libin A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Therapeutic robocat for nursing home residents with dementia: preliminary inquiry. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen April. 2004;19(2):111–6.

Marti P, Stienstra JT. Exploring empathy in interaction: scenarios of respectful robotics. GeroPsych J Gerontopsychology Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;26:101–12.

Wang RH, Sudhama A, Begum M, Huq R, Mihailidis A. Robots to assist daily activities: views of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr Januar. 2017;29(1):67–79.

Mitzner TL, Chen TL, Kemp CC, Rogers WA. Identifying the potential for Robotics to assist older adults in different living environments. Int J Soc Robot April. 2014;6(2):213–27.

Kelly D. Smart support at home: the integration of telecare technology with primary and community care systems. Br J Healthc Comput Inform Manage 1 April. 2005;22(3):19–21.

Woods O. Subverting the logics of “smartness” in Singapore: Smart eldercare and parallel regimes of sustainability. Sustain Cities Soc Februar. 2020;53:101940.

Jenkins S, Draper H, Care. Monitoring, and companionship: views on Care Robots from Older People and their carers. Int J Soc Robot 1 November. 2015;7(5):673–83.

Roberts C, Mort M. Reshaping what counts as care: older people, work and new technologies. Alter April. 2009;3(2):138–58.

Lee S, Naguib AM. Toward a sociable and dependable Elderly Care Robot: design, implementation and user study. J Intell Robot Syst April. 2020;98(1):5–17.

Bowes A, McColgan G. Telecare for Older People: promoting independence, participation, and identity. Res Aging Januar. 2013;35(1):32–49.

Morris ME. Social networks as health feedback displays. IEEE Internet Comput September. 2005;9(5):29–37.

Milligan C, Roberts C, Mort M. Telecare and older people: who cares where? Soc Sci Med 1982 Februar. 2011;72(3):347–54.

Sánchez VG, Anker-Hansen C, Taylor I, Eilertsen G. Older people’s attitudes and perspectives of Welfare Technology in Norway. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:841–53.

Faucounau V, Wu YH, Boulay M, Maestrutti M, Rigaud AS. Caregivers’ requirements for in-home robotic agent for supporting community-living elderly subjects with cognitive impairment. Technol Health Care 30 April. 2009;17(1):33–40.

Ropero F, Vaquerizo-Hdez D, Muñoz P, Barrero D, R-Moreno M. LARES: An AI-based teleassistance system for emergency home monitoring. Cogn Syst Res. 1. April2019;56.

Naick M. Innovative approaches of using assistive technology to support carers to care for people with night-time incontinence issues. World Fed Occup Ther Bull 3 Juli. 2017;73(2):128–30.

Obayashi K, Kodate N, Shigeru M. Can connected technologies improve sleep quality and safety of older adults and care-givers? An evaluation study of sleep monitors and communicative robots at a residential care home in Japan. Technol Soc 1 Juli. 2020;62:101318.

Palm E. Who cares? Moral Obligations in formal and Informal Care Provision in the light of ICT-Based Home Care. Health Care Anal Juni. 2013;21(2):171–88.

Korchut A, Szklener S, Abdelnour C, Tantinya N, Hernández-Farigola J, Ribes JC. u. a. challenges for Service Robots-Requirements of Elderly adults with cognitive impairments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:228.

O’Brien K, Liggett A, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara P, Lindquist LA. Voice-Controlled Intelligent Personal Assistants to support aging in place. J Am Geriatr Soc Januar. 2020;68(1):176–9.

Londei ST, Rousseau J, Ducharme F, St-Arnaud A, Meunier J, Saint-Arnaud J. u. a. An intelligent videomonitoring system for fall detection at home: perceptions of elderly people. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(8):383–90.

Melkas H. Innovative assistive technology in finnish public elderly-care services: a focus on productivity. Work Read Mass 1 Januar. 2013;46(1):77–91.

Peter C, Kreiner A, Schröter M, Kim H, Bieber G, Öhberg F. u. a. AGNES: connecting people in a multimodal way. J Multimodal User Interfaces 1 November. 2013;7(3):229–45.

Rawtaer I, Mahendran R, Kua EH, Tan HP, Tan HX, Lee TS. u. a. early detection of mild cognitive impairment with In-Home sensors to monitor behavior patterns in Community-Dwelling Senior Citizens in Singapore: cross-sectional feasibility study. J Med Internet Res 5 Mai. 2020;22(5):e16854.

Gokalp H, de Folter J, Verma V, Fursse J, Jones R, Clarke M. Integrated Telehealth and Telecare for Monitoring Frail Elderly with Chronic Disease. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. Dezember 2018;24(12):940–57.

Holthe T, Halvorsrud L, Lund A. A critical occupational perspective on user engagement of older adults in an assisted living facility in technology research over three years. J Occup Sci 2 Juli. 2020;27(3):376–89.

Wright J. Tactile care, mechanical hugs: japanese caregivers and robotic lifting devices. Asian Anthropol 2 Januar. 2018;17(1):24–39.

Mitseva A, Peterson CB, Karamberi C, Oikonomou LC, Ballis AV, Giannakakos C. u. a. gerontechnology: providing a helping hand when caring for cognitively impaired older adults-intermediate results from a controlled study on the satisfaction and acceptance of informal caregivers. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2012;2012:401705.

Snyder M, Dringus L, Maitland Schladen, Chenall R, Oviawe E. „Remote Monitoring Technologies in Dementia Care: An Interpretative Phe“ by Martha Snyder, Laurie Dringus[Internet]. 2020 [zitiert 13. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol25/iss5/5/

Suwa S, Tsujimura M, Ide H, Kodate N, Ishimaru M, Shimamura A. u. a. home-care professionals’ ethical perceptions of the Development and Use of Home-care Robots for older adults in Japan. Int J Human–Computer Interact 26 August. 2020;36(14):1295–303.

Torta E, Werner F, Johnson D, Juola J, Cuijpers R, Bazzani M. Evaluation of a Small Socially-Assistive Humanoid Robot in Intelligent Homes for the Care of the Elderly. J Intell Robot Syst. 1. Februar2014

Dinç L, Gastmans C. Trust and trustworthiness in nursing: an argument-based literature review. Nurs Inq September. 2012;19(3):223–37.

Moilanen T, Suhonen R, Kangasniemi M. Nursing support for older people’s autonomy in residential care: an integrative review. Int J Older People Nurs März. 2022;17(2):e12428.

Doorn N. Responsibility ascriptions in technology development and engineering: three perspectives. Sci Eng Ethics März. 2012;18(1):69–90.

Kooli C. COVID-19: public health issues and ethical dilemmas. Ethics Med Public Health Juni. 2021;17:100635.

Einav S, Ranzani OT. Focus on better care and ethics: are medical ethics lagging behind the development of new medical technologies? Intensive Care Med 1 August. 2020;46(8):1611–3.

Bahl R, Bahl S. Publication pressure versus Ethics, in Research and Publication. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med Dezember. 2021;46(4):584–6.

Pratt B, Hyder A. Fair Resource Allocation to Health Research: Priority Topics for Bioethics Scholarship - Pratt – 2017 - Bioethics - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. 2017 [zitiert 2. September 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12350

Malin B, Goodman K. Section editors for the IMIA Yearbook Special Section. Between Access and privacy: Challenges in sharing Health Data. Yearb Med Inform August. 2018;27(1):55–9.

Martani A, Egli P, Widmer M, Elger B. Data protection and biomedical research in Switzerland: setting the record straight. Swiss Med Wkly 24 August. 2020;150:w20332.

Price WN, Cohen IG. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat Med Januar. 2019;25(1):37–43.

Brady Wagner LC. Clinical ethics in the context of language and cognitive impairment: rights and protections. Semin Speech Lang November. 2003;24(4):275–84.

Sharkey A, Sharkey N. Granny and the robots: ethical issues in robot care for the elderly. Ethics Inf Technol März. 2012;14(1):27–40.

Berridge C, Demiris G, Kaye J. Domain experts on Dementia-Care Technologies: mitigating risk in design and implementation. Sci Eng Ethics 18 Februar. 2021;27(1):14.

Greshake Tzovaras B, Angrist M, Arvai K, Dulaney M, Estrada-Galiñanes V, Gunderson B. u. a. open humans: a platform for participant-centered research and personal data exploration. GigaScience 1 Juni. 2019;8(6):giz076.

Ienca M, Lipps M, Wangmo T, Jotterand F, Elger B, Kressig R. Health professionals’ and researchers’ views on Intelligent Assistive Technology for psychogeriatric care. Gerontechnology 8 Oktober. 2018;17:139–50.

Ienca M, Schneble C, Kressig RW, Wangmo T. Digital health interventions for healthy ageing: a qualitative user evaluation and ethical assessment. BMC Geriatr 2 Juli. 2021;21(1):412.

Wangmo T, Lipps M, Kressig RW, Ienca M. Ethical concerns with the use of intelligent assistive technology: findings from a qualitative study with professional stakeholders. BMC Med Ethics 19 Dezember. 2019;20(1):98.

Caregiving AARP. NA for. Caregiving in the United States 2020 [Internet]. AARP. 2020 [zitiert 31. August 2022]. Verfügbar unter: https://www.aarp.org/ppi/info-2020/caregiving-in-the-united-states.html

McGilton KS, Vellani S, Yeung L, Chishtie J, Commisso E, Ploeg J. u. a. identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 1 Oktober. 2018;18(1):231.

Sriram V, Jenkinson C, Peters M. Informal carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia care at home: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 14 Juni. 2019;19(1):160.

Schwabe H, Castellacci F. Automation, workers’ skills and job satisfaction. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0242929.

Huelat B, Pochron S. Stress in the Volunteer Caregiver: Human-Centric Technology Can Support Both Caregivers and People with Dementia. Medicina (Mex). 26. Mai 2020;56:257.

Edvardsson JD, Sandman PO, Rasmussen BH. Meanings of giving touch in the care of older patients: becoming a valuable person and professional. J Clin Nurs Juli. 2003;12(4):601–9.

Stöckigt B, Suhr R, Sulmann D, Teut M, Brinkhaus B. Implementation of intentional touch for geriatric patients with Chronic Pain: a qualitative pilot study. Complement Med Res. 2019;26(3):195–205.

Felber NA, Pageau F, McLean A, Wangmo T. The concept of social dignity as a yardstick to delimit ethical use of robotic assistance in the care of older persons. Med Health Care Philos März. 2022;25(1):99–110.

Ienca M, Wangmo T, Jotterand F, Kressig RW, Elger BS. Ethical design of intelligent assistive technologies for dementia: a descriptive review. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018;24(4):1035.

Zhu J, Shi K, Yang C, Niu Y, Zeng Y, Zhang N. Ethical issues of smart home-based elderly care: A scoping review. J Nurs Manag [Internet]. 22. November 2021 [zitiert 15. September 2022];n/a(n/a). Verfügbar unter: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13521

Talbert M. Moral Responsibility. In: Zalta EN, Herausgeber. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Internet]. Winter 2019. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2019 [zitiert 1. Juli 2020]. Verfügbar unter: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/moral-responsibility/

DeCamp M, Tilburt JC. Why we cannot trust artificial intelligence in medicine. Lancet Digit Health Dezember. 2019;1(8):e390.

Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum Resour Health 5 Juni. 2020;18(1):41.

Madara Marasinghe K. Assistive technologies in reducing caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older adults: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11(5):353–60.

Shah H. Algorithmic accountability. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci 13 September. 2018;376(2128):20170362.

Fiske A, Henningsen P, Buyx A. Your Robot Therapist will see you now: ethical implications of embodied Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy. J Med Internet Res 9 Mai. 2019;21(5):e13216.

Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare Januar. 2018;24(1):4–12.

Chasteen AL, Horhota M, Crumley-Branyon JJ. Overlooked and underestimated: experiences of Ageism in Young, Middle-Aged, and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 13 August. 2021;76(7):1323–8.

Svidén G, Wikström BM, Hjortsjö-Norberg M. Elderly Persons’ reflections on relocating to living at Sheltered Housing. Scand J Occup Ther 1 Januar. 2002;9(1):10–6.

McLean A. Ethical frontiers of ICT and older users: cultural, pragmatic and ethical issues. Ethics Inf Technol 1 Dezember. 2011;13(4):313–26.

Zwijsen SA, Niemeijer AR, Hertogh CMPM. Ethics of using assistive technology in the care for community-dwelling elderly people: an overview of the literature. Aging Ment Health Mai. 2011;15(4):419–27.

Jeong JS, Kim SY, Kim JN, Ashamed, Caregivers. Self-Stigma, information, and coping among dementia patient families. J Health Commun 1 November. 2020;25(11):870–8.

Mackinnon CJ. Applying feminist, multicultural, and social justice theory to diverse women who function as caregivers in end-of-life and palliative home care. Palliat Support Care Dezember. 2009;7(4):501–12.

Ha NHL, Chong MS, Choo RWM, Tam WJ, Yap PLK. Caregiving burden in foreign domestic workers caring for frail older adults in Singapore. Int Psychogeriatr August. 2018;30(8):1139–47.

Morales-Gázquez MJ, Medina-Artiles EN, López-Liria R, Aguilar-Parra JM, Trigueros-Ramos R, González-Bernal. JJ, u. a. migrant caregivers of older people in Spain: qualitative insights into relatives’ Experiences. Int J Environ Res Public Health 24 April. 2020;17(8):E2953.

Frennert S. Gender blindness: on health and welfare technology, AI and gender equality in community care. Nurs Inq Dezember. 2021;28(4):e12419.

Starke G, van den Brule R, Elger BS, Haselager P. Intentional machines: a defence of trust in medical artificial intelligence. Bioethics. 2022;36(2):154–61.

Ozaras G, Abaan S. Investigation of the trust status of the nurse-patient relationship. Nurs Ethics August. 2018;25(5):628–39.

Berridge C, Turner NR, Liu L, Karras SW, Chen A, Fredriksen-Goldsen K. u. a. Advance Planning for Technology Use in Dementia Care: Development, Design, and feasibility of a Novel Self-administered decision-making Tool. JMIR Aging 27 Juli. 2022;5(3):e39335.

Acknowledgements

We thank the information specialist of the University of Basel who advised us on our search strategy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel. This study was supported financially by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF NRP-77 Digital Transformation, Grant Number 407740_187464/1) as part of the SmaRt homES, Older adUlts, and caRegivers: Facilitating social aCceptance and negotiating rEsponsibilities [RESOURCE] project. The funder neither took part in the writing process, nor does any part of the views expressed in the review belong to the funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Creation of the search strategy and data extraction was a joint effort of NAF and AT. FP and TW extracted data and prepared it for analysis. AT contributed majorly to the data analysis, together with NAF who is the first author of this manuscript. TW and BE provided final comments and edits. All authors read and approved the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

not applicable.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Felber, N.A., Tian, Y., Pageau, F. et al. Mapping ethical issues in the use of smart home health technologies to care for older persons: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 24, 24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00898-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00898-w