Abstract

Background and objectives

Smart technology in nursing home settings has the potential to elevate an operation that manages more significant number of older residents. However, the concepts, definitions, and types of smart technology, integrated medical services, and stakeholders’ acceptability of smart nursing homes are less clear. This scoping review aims to define a smart nursing home and examine the qualitative evidence on technological feasibility, integration of medical services, and acceptability of the stakeholders.

Methods

Comprehensive searches were conducted on stakeholders’ websites (Phase 1) and 11 electronic databases (Phase 2), for existing concepts of smart nursing home, on what and how technologies and medical services were implemented in nursing home settings, and acceptability assessment by the stakeholders. The publication year was inclusive from January 1999 to September 2021. The language was limited to English and Chinese. Included articles must report nursing home settings related to older adults ≥ 60 years old with or without medical demands but not bed-bound. Technology Readiness Levels were used to measure the readiness of new technologies and system designs. The analysis was guided by the Framework Method and the smart technology adoption behaviours of elder consumers theoretical model. The results were reported according to the PRISMA-ScR.

Results

A total of 177 literature (13 website documents and 164 journal articles) were selected. Smart nursing homes are technology-assisted nursing homes that allow the life enjoyment of their residents. They used IoT, computing technologies, cloud computing, big data and AI, information management systems, and digital health to integrate medical services in monitoring abnormal events, assisting daily living, conducting teleconsultation, managing health information, and improving the interaction between providers and residents. Fifty-five percent of the new technologies were ready for use in nursing homes (levels 6–7), and the remaining were proven the technical feasibility (levels 1–5). Healthcare professionals with higher education, better tech-savviness, fewer years at work, and older adults with more severe illnesses were more acceptable to smart technologies.

Conclusions

Smart nursing homes with integrated medical services have great potential to improve the quality of care and ensure older residents’ quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The ageing population is associated with increased demand in healthcare, and they would require a wide range of assistance in physical mobility and daily monitoring [1]. Smart technologies could help older adults extend their independence and well-being [2]. In the earlier stage, many sensors and actuators were used as a ubiquitous environment (u-healthcare) to monitor patients [3]. IBM’s (International Business Machines Corporation) first introduced the concept of ‘Smarter Planet’ [4], which was briefed as ‘smart’. Later, smart technologies were associated with a range of information technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence (AI) in the medical field [5]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) (2019) links smart healthcare with digital health, including telemedicine and mobile health (mHealth) [6].

Smart technologies empower older adults to ‘live in place’ and lead their activities to maintain a quality of life [7]. Several studies have proven that smart technologies were feasible to apply in health monitoring, disease prediction, and detection of abnormal situations for home-based care residents [8, 9]. However, admission to nursing homes is usually a significant life event for most older adults due to the changes in health conditions with complex needs in healthcare [10]. Using smart technology in nursing home settings provides residents a more comfortable and safe environment [11]. Nursing homes integrating smart technologies could benefit caregivers by saving time and reducing unnecessary workload while providing efficient and effective care services for residents, such as using wearable devices to collect biometric data [12]. Moreover, it is possible to reduce healthcare costs by using more efficient healthcare resources [13].

Globally, the quality of care in most nursing homes is suboptimal, and the concerns are about the shortages of doctors and nurses, skills of nursing home staff, and safety of medical operations [14,15,16]. Many nations are seeking solutions for alternative senior care to cope with the challenges of the ageing population and encouraging technique innovation in real-time monitoring of diseases, mobile phone-based healthcare assistance, electronic health record, and telemedicine at nursing homes [17]. As one of the countries in the world facing the ‘grey tsunami’, the Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs, a nursing home supervision department, initiated a report to promote IoT-based projects for senior institutional care. The Chinee government would financially support the pilot projects in health monitoring, fall detection, location tracking, and any innovation in big data management or analysis [18]. However, a clear concept of technique-assistant nursing home and the appropriate technologies related to ‘smartness’ is yet to be defined [19, 20].

Accordingly, a scoping review is needed to provide a smart nursing home model which includes a definition and the availability of smart technologies to meet the demands and aspirations of potential customers, such as older adults and their family members. Standardising the definition and service scope of smart nursing homes would help introduce appropriate smart technologies in the nursing home settings. A clear concept would also allow stakeholders to evaluate and monitor the operations of smart nursing homes with an evidence-based reference and enhance their acceptability of the smart nursing home model [21].

Theoretical model

The smart technology adoption behaviours of elder consumers theoretical model by Golant (2017) is adopted to guide this scoping review (Fig. 1) [22]. The model offers an adequate explanation of older adults’ coping process regarding adopting smart technologies. The coping process may come from the older adults’ unmet needs in daily life, the user perspective of perceived efficaciousness (usefulness, relative advantage of adoption), usability (easy or complex of use), and collateral damages (unintended harms of use) until deciding to adopt the ‘new’ solution. This coping process is also influenced by internal information (potential users’ past experiences) and external information such as the cues, tips or persuasions of friends, family members, and doctors on the potentials of technology, electronic devices or smart gadgets in daily living. Other factors such as user sociodemographic characteristics may affect their acceptability. The non-senior stakeholders, for example, the healthcare professionals (HCPs), may have the same coping process when considering the older adults’ unmet needs. This model is appropriate for formulating the review objectives.

The Smart Technology Adoption Behaviors of Elder Consumer Theoretical Model (Golant, 2017) [22]

Review objectives

This scoping review was conducted to map the concepts of smart nursing homes systematically and to examine the qualitative evidence on technological feasibility, integration of medical services, and the stakeholders’ acceptability of smart nursing homes, including the older adults aged ≥ 60 years old and their caregivers [23].

Method

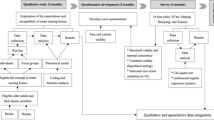

Extended and comprehensive searches were conducted on stakeholder websites for existing concepts of smart nursing homes and the criteria of services (Phase 1). The search was continued on the 11 electronic databases for technologies and integrated medical services implemented in nursing home settings, as well as the acceptability as reported by stakeholders, including nursing home residents and HCPs (Phase 2). The eligible articles searched in Phase 2 were included for extracting the definition of smart nursing homes and the criteria of services if they stated the respective information. Technology Readiness Level (TRL) was adopted to evaluate the feasibility and the maturity of a newly developed technology for future implementation [24]. The data analysis was guided by the Framework Method [25] and the smart technology adoption behaviours of elder consumers theoretical model [22]. Results were reported according to the PRISMA-ScR [26] (Supplementary file 1).

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria include: 1) concepts or definitions of smart nursing home; 2) nursing home residents aged ≥ 60 years old with or without medical demands but not bed-bound; 3) assessment of any health information technologies or models that were considered ‘smartness’ in nursing home settings; 4) perception and acceptability of smart nursing homes by the older adults and other stakeholders; 5) challenges and recommendations to implement information technologies that facilitate medical services in nursing homes. Other articles irrelevant to the study objectives or not in nursing home settings were excluded, for example, the smart technologies applied in home-based settings or technologies used in entertainment, environmental control, and transportation for older adults.

Information sources and search strategy

Following the plan of the published study protocol [20], the search on stakeholder websites was conducted on three popular search engines for the statement of smart nursing homes, including ‘Google’, ‘Yahoo’ and ‘Baidu (a Chinese engine)’. The search used the following Chinese and English keywords sequentially: ‘Yang Lao Yuan’ (nursing home in Chinese) and followed by ‘smart nursing home’, ‘concept of smart nursing home’, ‘definition of smart nursing home’, ‘criteria of smart nursing home’, and ‘standard of smart nursing home’.

Additionally, the keywords: smart nursing home, smart health*(care), Internet of Things (IoT), digital health*, remote health*(care), telemedicine, mobile health*(care), mHealth (including telemedicine), eHealth, point-of-care, wireless sensor network (WSN), artificial intelligence (AI) and ubiquitous healthcare (u-healthcare) were used for searching the published articles on technological feasibility, integrated medical services, and user acceptability on the English bibliographic databases (PubMed, IEEE Explore, CINAHL, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Health Systems Evidence, Social Systems Evidence, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection). The keywords applied on the selected Chinese bibliographic databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure and the Wanfang Data) were the Chinese description of smart nursing homes, for example, Zhi Neng Yang Lao Yuan, Zhi Hui nursing Yang Lao Yuan, and Yi Liao Kang Yang. The language was limited to English and Chinese. The publication year was limited to those published between January 1999 and May 2020, as the label ‘smart dust technology’ was first introduced in 1999 to describe the limited size of wireless sensor networks and millimeter-scale nodes [27]. Supplementary file 2 provides the search strategy on databases. An updated search was conducted on the 11 bibliographic databases by using the same method to identify the latest publication from May 2020 to September 2021. Due to the license from the university, the search on Scopus was updated to December 2019.

Selection of sources of evidence

A comprehensive screening of eligible articles was conducted by a reviewer (YYZ). All sources were imported into the Endnotes X9 library, and the duplicates have been removed. Endnotes X9 library was shared with a second reviewer (NKD). Documents in the Chinese language were double reviewed by another reviewer (JS). Eligible criteria were applied to both abstracts and full texts. This scoping review was conducted to provide an overview of the existing evidence of smart nursing home concepts, technological feasibility, integration of medical services, and stakeholders’ acceptability of smart nursing homes regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias [26]. Quality appraisal of reviewed literature and individual source of evidence was not applicable. The third reviewer was involved in the discussion and decided the results when two reviewers had disagreements in the selection process.(FKR, SSG and BHC).

Data charting

The Framework Method is used to thematically analyse the qualitative data in this scoping review. It is a comparative form of thematic analysis that combines inductive and deductive approaches to analyse texture data and summarise the results, such as using a combination of data description and abstraction (codes and themes) [20]. The data from stakeholder websites and electronic databases were categorised by type of smart technology, technology function, direct user, integrated medical services, and stakeholder acceptability. Three investigators (YYZ, NKD, and JS) extracted the textual statements on the concept of smart nursing homes, implemented technologies, the integration of medical services, and stakeholders’ acceptability. Preliminary codes and themes related to the research objectives were named after the most frequently recurring terms within the same clusters, and the generalisability of textural data gave those names. The codes labelled for stakeholders’ acceptability were referred to the theoretical model [22]. Data extraction and translation from Chinese to English were also done (YYZ). The individual data extraction and analysis were subsequently discussed by all investigators (YYZ, FKR, SSG, and BHC). The coding categories were defined and refined until at least three investigators reached a consensus.

Results

A total of 177 pieces of literature (Fig. 2 and supplementary file 3) were selected for review comprising 13 documents from stakeholders’ websites (Phase 1) and 164 articles from bibliographic databases (Phase 2).

Phase 1: Definition, concepts and criteria of a smart nursing home

Thirty documents and articles (supplementary file 3) were included to retrieve the definitions, concepts, and criteria of smart nursing homes. Of these, there were 13 documents searched from the stakeholder websites in Phase 1 and 17 research papers in Phase 2. The sources of the 13 documents from stakeholder websites were government authorities (n = 4), smart technology providers (n = 4), home pages of nursing home (n = 3), construction company of nursing home (n = 1), and respective research institute (n = 1).

The qualitative analysis generated three themes related to the concept of smart nursing homes (Table 1): 1) application of smart technologies, 2) technology-assisted nursing care, and 3) combination of smart home and hospital models. In addition, quality of care (QoC) defined by WHO [28] was adopted and applied to measure the criteria and outcome of smart nursing home services that are provided to its residents. In order to achieve better services, health care must be safe, effective, timely, efficient, equitable, and people-centered [28].

The qualitative analysis defined a smart nursing home as a collective or individual senior care model. In particular, the smart nursing home integrates the older adults’ daily routine of life and healthcare needs with information technologies or engineering to provide continuous monitoring for its residents, connect communication within its care providers, and conduct teleconsultation with external medical resources. Technology-assisted nursing care ensures life enjoyment in an affordable and safe environment. The smart nursing home services with immediate health attention and people-centered respect are effective, efficient, and evidence-based. Supplementary file 4 presents the quotations and the categories of the code.

Phase 2: Technological feasibility, integration of medical services and acceptability

A total of 164 articles from 28 countries and regions across four continents were eligible for data extraction. Two of the 164 articles, including an editorial on bringing smart technologies into a nursing home [47] and one system design of engineering methodology [55], were only eligible to be included for exacting the definition of smart nursing homes. There were 162 articles searched in Phase 2 (Table 2) were included to extract the technological feasibility, integration of medical services, and stakeholders’ acceptability. Out of these, 50% (n = 81) were studies of system designs, 7% (n = 12) experimental, 23% (n = 38) non-experimental, 8% (n = 13) qualitative studies, 3% (n = 4) mixed methods, 9% (n = 14) non-research articles including literature reviews, perspective, and editorial. Fifty-seven percent (n = 93) were journal articles, 31% (n = 50) conference papers, 9% (n = 15) student dissertations/theses, and 3% (n = 4) book chapters. Most resources were from the USA (n = 40) and China, including Taiwan (n = 41).

Technologies related to ‘smartness’

Smart technologies offer much more interaction between the nursing home resident and HCPs, enhance safety, and improve the quality of care [11, 202]. Out of 162 articles, 41% articles (n = 66) reported on IoT, 35% (n = 57) on digital health, 12% (n = 20) on information management system (IMS), 8% (n = 13) on big data and AI, 3% (n = 5) on computing technologies and 1% (n = 1) on cloud computing.

Functions of smart technology in nursing home settings and direct users

Forty-seven percent of included articles (n = 76) reported technologies for monitoring and notification of abnormal events, such as health monitoring, fall detection, and location tracking, 35% (n = 57) for remote clinical services through digital health, 12% (n = 20) for information management and decision making, 3% (n = 5) for clinical data analysis by AI approach, and 3% (n = 4) for daily living assistance. The direct users of those smart technologies were nursing home residents (n = 132) and HCPs (n = 30), such as nursing home staff and health professionals in remote hospitals which provided health services for nursing homes. There were none related to family members as the direct users.

Monitoring and notification of abnormal events

Monitoring devices have been proven to ensure the safety of the nursing home residents in fall prevention [52, 76, 84, 95, 96, 100, 107, 110,111,112, 114,115,116], automatic monitoring of health conditions, and notification of emerging events, such as heart attacks and fatal accidents [11, 12, 19, 31, 33, 37,38,39, 41, 51, 54, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83, 85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94, 97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109, 113, 118, 202, 203]. The vital sign of older adults could be collected and recorded by the wearable devices, such as clothes and shoes on nursing home residents [96, 106]. Sensors were installed in the mattresses and rooms to monitor the older adults’ behaviours and sleeping quality, especially used for residents with limited mobility [51, 90]. Biosensors, ultrasonic sensors, infrared sensors, radio frequency identification (RFID), and GPS were mainly used with IoT terminals [71, 77, 83, 87]. Cameras, mobile devices, and personal computers were embedded with sensor networks to assist the real-time monitoring. Family members could also be given access to the real-time monitoring of their senior family members in the nursing homes [95]. Such a solution improved care efficiency and decision-making of nursing home HCPs, especially in managing a large number of nursing home residents with cognitive disorders [94].

Remote clinical services through digital health

Digital health, including telemedicine and mHealth, has shown to benefit the older adults in nursing homes in rural areas with good internet or communication coverage [119, 120, 122, 124, 126, 127, 131,132,133,134, 136, 137, 139, 141, 146, 148, 149, 151, 152, 154, 156,157,158,159,160,161,162, 166, 168, 204]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine reduced unnecessary hospitalisation [170, 175]. Digital images of the residents could be transmitted in real-time to hospital specialists, and that enabled the electronic stethoscopes, otoscopes, dermoscopic, dental scopes, and electrocardiograms to be implemented through the internet and live video to assist clinical practices [128]. Telehealth and mHealth were widely applied in managing cognitive disorders [145, 153, 172], dermatologic conditions [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144], cardiovascular diseases [124, 137, 173], diabetes mellitus [143], rehabilitation of disabilities [147, 202], dentistry [163] and ophthalmology [171] in the distance. The portable X-ray machine attached with mobile devices successfully conducted x-ray for nursing home residents to reduce unnecessary transmission to the hospitals, and the services were of comparable quality to hospital-based examinations [130, 140, 150, 155, 161]. Telemedicine with designed software helped doctors to prescribe medicines remotely and avoid adverse drug events [123, 142].

Information management and decision making

There was a growing use of electronic documentation in many nursing homes requiring proper information management for patients’ medical records, nursing projects, care quality assessment, clinical task schedule, and medication records [179, 180, 186, 188]. The health information of nursing home residents was manually collected by nursing home staff or through technology-based devices, such as mobile phones, tablets, personal computers, and sensors to input into the electronic medical records (EMR) systems [182, 187]. The information management systems also improved clinical decision-making by sharing and tracking patients’ medical records and enhanced HCPs’ communication to reduce errors in clinical practices [53, 176,177,178, 181, 183,184,185, 187, 189, 191, 193, 194].

Clinical data analysis by AI

AI approach helped with health-related parameter analysis and big data management [35, 197]. Using AI to analyse biometric data collected from older adults enabled the identification of potential relationships between parameters and frailty [196, 198]. As an emerging technology, big data analytics, data mining, and classification used in nursing home management would transform the available data into structured knowledge, enhance data reliability, and enable accurate diagnosis, such as detection of disuse syndrome [88].

Activities of daily living (ADLs) assistance

Based on the IoT and computing technologies, smart toolkits have been developed to assist older adults with chronic diseases in their activities of daily living, for example, smart pill-boxes with automagical medication reminders, recording, and pill-dispensing that helped them in taking their daily medications to improve medication adherence [199,200,201]. Humanoid robots were developed to monitor nursing home residents’ activities and ensure their safety in certain areas [50].

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) measurement

TRL classifies nine levels of developmental stages, from basic principles and technology concepts formulated to the completion and proof of actual system [205]. Of the 81 articles on system designs, three [83, 90, 117] were not able to be evaluated by TRLs because these were only abstracts with inadequate information, 6.5% (n = 5) were judged to be at level 1, 15% (n = 12) at level 2, 14% (n = 11) at level 3, 6.5% (n = 5) at level 4, 4% (n = 3) at level 5, 19% (n = 15) at level 6, and 35% (n = 27) at level 7 (Table 3). Among newly developed technologies, 82% (n = 64) were applications for health and abnormal events monitoring, fall detection, and notification systems. The remaining 18% (n = 14) were related to activities of daily living assistance, information management, big data analysis, and remote clinical services.

Integration of medical services

Forty-four out of 162 articles reported the integration of medical services in nursing homes. Telemedicine (31/44, 70%), mHealth (10/44, 23%), and clinical information management (3/44, 7%) were used to integrate medical services from distant hospitals and clinical specialists to assist the nursing homes (Table 4 and supplementary file 5).

Integration of medical services in telemedicine

The integration of medical services was widely used in the field of telemedicine, for example, videoconferencing (16/31, 52%), telemonitoring (8 /31, 26%), information technologies (5/31, 16%), and remote specialist decision making systems (2/31, 6%) have been integrated to overcome the issues of accessibility and timeliness of medical services for nursing home residents. As a form of telemedicine, teleconsultation integrating real-time videoconference was applicable to replace face-to-face consultations in nursing homes through videophones or computers combined with cameras and microphones, and it enhanced clinical efficiency and cost-effectiveness of healthcare delivery [127, 128, 138, 145]. Teleconsultation integrated health monitoring devices, such as mobile phones or smartwatches, provided a telemonitoring service to record heart rate and blood pressure electronically, and it enabled the HCPs to take prompt responses to the older adults’ urgent health conditions in remote nursing homes [19, 51, 62, 115, 154, 191]. Telemedicine integrated computing technologies have been shown to help remote HCPs make good decisions in clinical management after reviewing patients’ digital health records, which were shared through emails or web-based health management systems [125, 133, 144, 172].

Integration of medical services through mHealth

Abnormal events monitoring [78, 88, 95, 202], radiography [150, 166, 206], and teleconsultation [139, 147, 171] could be implemented through mobile devices. mHealth personalised nursing home services, improved efficiency in the closer connection between HCPs and nursing home residents, lowered incidences of unnoticed events, and ensured the residents’ quality of life [142]. Mobile devices connected with sensor-based devices enabled HCPs to monitor and interact with older adults in real-time, and abnormal events such as activities related to falls would be reported to prevent [88]. Mobile applications could assist HCPs at point-of-care in scheduling clinical tasks, performing radiography, digitally recording their clinical practices resulting in time-saving and error reduction [166]. Besides, personal mobiles or tablets were used to connect nursing home residents to conduct teleconsultation [139].

Integration of clinical information

Integration of clinical information could improve the quality of care in different medical organisations, for example, sharing patients’ clinical information between nursing homes and differently external care departments, such as the department of pathology, pharmacy, physical therapy, and other social agents, increased valuable support for nursing care, enhanced coordination with multiple specialty consultants, and improved administrative practices [187, 188].

Stakeholders’ acceptability

Guided by the theoretical model proposed by Golant (2017) [22], the scoping review observed both the expected and unexpected reasons related to stakeholders’ acceptability of smart technologies. In addition, individual attributes were associated with the adoption of smart technologies (Table 5 and supplementary file 6).

Persuasiveness of external information and internal information

Older adults became more aware and willing to use new technology when persuaded or compelled by the potential benefit of the technology from external resources, for example, their family members or HCPs [76, 135]. This coping process is also influenced by internal information, such as user-experienced helpfulness, ease of use, and safety features of the technology [140, 149]. These factors resulted in user satisfaction and enhanced positive attitudes to the final adoption of smart technologies [68, 124].

Perceived efficaciousness

The nursing home residents who had experienced or perceived the usefulness of smart technologies in meeting their healthcare demands were more accepting of the technologies [54]. Similarly, HCPs perceived helpfulness in assisting care delivery to improve care efficiency increased their acceptability of smart technology, for example, using health information exchange systems efficiently improved doctor-patient communication [188]. Using smart technologies to improve HCPs’ daily routines, enhance medication safety, and deal with the events of emergencies could be a better solution to ensure the quality of care in nursing homes and the older adults’ quality of life [120, 142].

Perceived usability (positive and negative)

Smart technology improved access to healthcare for nursing home residents [140]. The users increased their awareness and consideration of adopting smart technologies when they recognised that smart solutions would be necessary for care [75, 152]. The appraisals of new technology on ease of use or ease to learn [129, 133, 149], user-friendly [71, 129, 184], and convenience [122, 147] in the coping process enhanced user acceptability of smart technology. Users also preferred the “human-centric” designs to fit their lifestyles [76, 99]. The affordability of smart technology is one of the considerations in the coping process, for example, the smart solution would be better accepted if the cost was not higher or not more expensive than the conventional care model [76]. HCPs expected adequate tech support and regular training in applying new technology to enhance the user engagement, confidence, and continuous operation [138, 184]. In addition, appropriate domestication of new technology could improve user acceptability [157]. Domestication is a dynamic process when users in various environments adapt and start to use the new technologies [207].

In contrast, the features of unusefulness or uncertainty of using smart technologies in the coping process were reported to affect the user acceptability negatively, such as the unusefulness [129, 149], difficulty in use or to learn [101, 208], and lacking supportive resources [169, 177] or tech-support in applying technologies [178]. Some HCPs perceived new technologies as a burden to disrupt routines or added workloads, and it may cause reducing their time to provide essential nursing care for the residents, for example, initiating a new information system requiring manual input of residents’ health records into the system caused frustrations among the HCPs [71, 181].

Perceived collateral damages

Potential medical risks, sensitivity and reliability of technology, errors during the operation, and increased costs were the main concerns that have been reported [135, 149, 152] associated with the unintended and harmful effects of using smart technology [22].

Acceptability differs by the attributes of residents and HCPs

Attributes of residents and HCPs were observed to associate with the acceptability and adoption of smart technologies. The attribute of residents identified from the reviewed articles was the severity of illness [71]. The attributes of HCPs in positively accepting smart technologies in nursing homes were higher educational attainment [126], a few of year working experience (younger age), and better tech-savviness [54, 133, 142].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that identified the gaps and scope of evidence on the concept of a smart nursing home, explored the smart technologies in nursing home settings, and described medical services that could be integrated and implemented in nursing homes. We evaluated the feasibility of innovative technologies in development by applying the TRLs. This review has also captured the stakeholders’ acceptability of smart technologies, especially from the perspectives of older adults and HCPs.

Previous studies described a smart nursing home as a smart building equipped with IoT technologies [35]. This scoping review concluded that nursing home residents’ health status and emergency situations were mainly monitored and collected by sensors through wearable devices, and the sensors installed on walls less on the user themselves achieved comfort and safe environment [11, 33]. In particular, a smart nursing home would offer technology-assisted nursing care for older adults with the needs of health monitoring, activities of daily living, and safety [37, 209]. Based on their demands, a comprehensive concept of smart nursing homes has to be supported by smart technologies to provide integrated nursing care, personalised monitoring of abnormal events, and assistance in activities of daily living. This smart nursing home model also emphasises the integration of medical services from remote clinical specialists and hospitals to support nursing and medical cares that are convenient, comfortable, and safe to the residents [11]. The services in smart nursing homes could be more effective and efficient in care delivery to achieve the expectations of all stakeholders, including the nursing home residents, family members, and nursing home staff [12]. Figure 3 illustrates the concept of a smart nursing home.

The feasible smart technologies in nursing homes reported in the literature can be classified as IoT, computing technologies, cloud computing, big data and AI, information management system, and digital health. A few published articles classified the most important functions of smart technology in hospital and home-based care settings as health status and mobility monitoring [210]. Hospitals used smart technologies to improve clinical decision-making [21], while in home-based care, smart technologies assisted in the self-management of chronic diseases and remote health monitoring [211, 212]. In nursing homes, the feasible technologies were mainly used in monitoring residents’ abnormal events, connecting to remote clinical services, managing clinical information, analysing big data, and developing device to for the older adults’ to assist their activities of daily living. The TRL evaluation showed that 54% of new system designs were at levels 6 and 7, which have been proven ready for use in nursing homes. The technology function was mainly for monitoring abnormal events in nursing homes. The development of these new technologies is ready to progress to the higher levels of TRL 8 and 9 for commercialisation and future public use. Therefore, the technologies supporting ‘ageing in place’ were developed more maturely, and some of the technologies such as the applications of health monitoring, ADLs, and safety improvement have reached TRL 8 and 9 [209].

Integrating medical services could achieve clinical efficiency and overcome the limited access to healthcare for the older adults who live in rural area [213]. Electronic clinical information, telemedicine, and mHealth have shown the feasibility in overcoming shortages of medical resources and improving healthcare access in nursing homes [169]. The scoping review found that clinical information management and remote clinical services, especially telemedicine, have been broadly implemented in some nursing homes and they were accepted by many stakeholders [147]. With the effective implementation of smart technologies and integration of medical services, many nursing homes could manage a large number of residents and provide customised care to older adults [104].

The theoretical model [22] indicated that the potential users’ persuasiveness of external and internal information, perceived efficaciousness, perceived usability, and perceived collateral damages of using smart technologies determined their acceptability of smart solutions. This scoping review identified and extracted the same determinants from the reviewed articles. In addition, the older adults’ severity of illnesses, the users with a higher level of education and better tech-savviness, and the HCPs with fewer years of working experience (younger age) were associated with higher acceptability of smart technologies [54, 71, 126, 133, 142]. These findings were consistent with the results from a literature review in a home-based care setting. The identified factors that influenced users' technology acceptability included positive experiences with using technologies, such as ease of use, increased safety, security for care, perceived need to use, concerns of technical errors, social influence, and older adults' physical conditions [209]. However, the older adults’ unmet needs and the description of their resilience to smart technology did not mention in the reviewed articles. The older adults did not seem to take concrete actions to adopt a smart technology according to their stressful unmet needs or the different levels of resilience to adversity from the new technologies as indicated in the theoretical model [22].

There are some limitations to be aware of when using the findings in this review. Business reports were not published in the 11 selected databases we searched, and it might cause the review to miss the new technologies or actual systems that have been approved to use in the nursing homes (TRL 8 and 9). Nevertheless, the number and types of databases this review has conducted searches on are believed to have captured informative literature to the review objectives. Meta-analysis and quality assessment were not applicable in this scoping review because the literature and studies informed about the scope and extent of the smart nursing home concepts, technology utilities with its integrated medical services, and acceptability by stakeholders disregarding the literature risk of biases. In the future, researchers could explore the characteristics and feasibility of smart technologies implemented in nursing homes by the particular functions that we categorised, for example, the technologies in the monitoring of abnormal events and activities of daily living assistance.

Conclusion

Smart nursing homes with integrated medical services have great potential to be a future trend to replace the conventional nursing home. The motivation for transferring from a conventional model to a smart one includes having advanced and safe information technologies, well-trained staff who deliver the nursing care and medical services, and meeting the expectations of all stakeholders. However, technology readiness for frontier technologies, such as clinical data analysis by AI approach and cloud computing technologies, needs to catch up even though much has been presented already, such as the IoT, telemedicine, and information management system. The technology appraisal process was determined by perceived efficaciousness, perceived usability, and perceived collateral damages of adopting the smart technology. Older adults living with severe illnesses and who were persuaded of the benefit of adopting smart solution by the external and internal resources were more accepting of new technologies in nursing homes. Meanwhile, the HCPs with higher educational attainment, fewer years of working experience, and better tech-savviness had higher acceptability of smart technologies.

This scoping review is relevant to a broad base of readers interested in this research and most developed and developing countries with nursing homes. The scoping review results may contribute to future research on introducing smart technologies into nursing homes or developing a successful smart nursing home model. The identified smart technologies that integrate multidisciplinary, such as biomedical informatics and medicine, may provide the technical scope of the smart nursing home model for all stakeholders. The results are also applicable in the planning, evaluating, and monitoring the feasible technologies and service criteria when smart nursing homes are integrated with different types of medical services.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations

- IoT:

-

Internet of Things

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- HCPs:

-

Healthcare professionals

- TRL:

-

Technology readiness level

- ADLs:

-

Activities of daily living

References

Bzura C, Im H, Malehorn K, Liu W. The Emerging Role of Robotics in Personal Health Care: Bringing Smart Health Care Home. 2012.

Sokullu R, Akkaş MA, Demir E. IoT supported smart home for the elderly. Internet of Things. 2020;11:100239.

Brown I. Adams AAJIRoIE. Ethical Challenges Ubiquitous Healthcare. 2007;8(12):53–60.

IBM. Smarter Planet IBM website2008 [Available from: https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/smarterplanet/.

Tian S, Yang W, Grange JML, Wang P, Huang W, Ye Z. Smart healthcare: making medical care more intelligent. Global Health Journal. 2019;3(3):62–5.

WHO. WHO guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Demiris G, Hensel BK. Technologies for an aging society: a systematic review of “smart home” applications. Yearb Med Inform. 2008;17(01):33–40.

Rantz M, Phillips LJ, Galambos C, Lane K, Alexander GL, Despins L, et al. Randomized trial of intelligent sensor system for early illness alerts in senior housing. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(10):860–70.

Ni Q, Garcia Hernando AB, la Cruz D, Pau I. The elderly’s independent living in smart homes: a characterization of activities and sensing infrastructure survey to facilitate services development. Sensors. 2015;15(5):11312–62.

Serow WJ. Why the elderly move: cross-national comparisons. Res Aging. 1987;9(4):582–97.

Gamberini L, Fabbri L, Orso V, Pluchino P, Ruggiero R, Barattini R, et al. A cyber secured IoT: Fostering smart living and safety of fragile individuals in intelligent environments. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; 2018. p. 335-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05921-7_27.

Huang P, Lin C, Wang Y, Hsieh H, editors. Development of Health Care System Based on Wearable Devices. 2019 Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM-Paris); 2019 2–5 May 2019.

Raja T. Internet of things: benefits and risk of smart healthcare application. Innovation. 2016;10(3):37–42.

Chu L-W, Chi I. Nursing homes in China. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(4):237–43.

Tolson D, Rolland Y, Andrieu S, Aquino J-P, Beard J, Benetos A, et al. International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics: A global agenda for clinical research and quality of care in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(3):184–9.

Xie W, Fan R, editors. Towards Ethically and Medically Sustainable Care for the Elderly: The Case of China. HEC Forum. 2020;32(1). Springer.

WhiteHouse. Emerging Technologies to Support an Aging Population. USA: Committee on Technology of the National Science & Technology Council; 2019.

MCA. Ministry of Civil Affairs Releases "Demonstration Project on the Application of Internet of Things for Smart Aging‘: Department of Social Welfare Promotion; 2014 [Available from: http://news.21csp.com.cn/c3/201406/72132.html.

Wang J. Research on the application of distributed smart ageing system based on data fusion [Master thesis]: Shen Yang University; 2014.

Zhao Y, Rokhani FZ, Ghazali SS, Chew BH. Defining the concepts of a smart nursing home and its potential technology utilities that integrate medical services and are acceptable to stakeholders: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e041452.

Mieronkoski R, Azimi I, Rahmani AM, Aantaa R, Terävä V, Liljeberg P, et al. The Internet of Things for basic nursing care—A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:78–90.

Golant SM. A theoretical model to explain the smart technology adoption behaviors of elder consumers (Elderadopt). J Aging Stud. 2017;42:56–73.

GOV.cn. Law of the people's republic of China on protection of the rights and interests of the elderly: The State Council, The People's Republic of China; 2012 [Available from: http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2012-12/28/content_2305570.htm.

Mankins JC. Technology readiness levels. White Paper, April. 1995;6:1995.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Kahn JM, Katz RH, Pister KS, editors. Next century challenges: mobile networking for “Smart Dust”. Proceedings of the 5th annual ACM/IEEE international conference on Mobile computing and networking; 1999.

WHO. What is Quality of Care and why is it important? [Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/quality-of-care.

Baidu, Smart Aging Cloud Service Platform 2018. 2018. https://wenku.baidu.com/view/d100cd6c4a73f242336c1eb91a37f111f1850d93.html?re=view.

Ce.cn. IoT+Big Data+Wisdom for the elderly in Wuxi: China Economic Network. 2019. https://www.yanglaoditu.com/news/industry/11217.html.

Chen D, Li W. Circuit design that can be used for smart nursing home system terminals. Chin J Electron Devices. 2012;35(3):357–60.

Korte. Delivering World-Class Care and Quality of Life-The Owner's Guide to Senior Liver Design and Construction. 2020. https://www.korteco.com/sites/default/files/KORsenior-living-v8.pdf.

Lee S, Shin I, Lee N, editors. Development of IoT based Smart Signage Platform. 2018 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC); 2018 17–19 Oct. 2018.

Mahieu C, Ongenae F, De Backere F, Bonte P, De Turck F, Simoens P. Semantics-based platform for context-aware and personalized robot interaction in the internet of robotic things. J Syst Softw. 2019;149:138–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.11.022.

Roh EH, Park SC. A study on the quality of life improvement in fixed IoT environments: Utilizing active aging biomarkers and big data. Quality Innovation Prosperity. 2017;21(2):52–70.

Shenghuo. Location of good smart nursing homes in Guangzhou: Life Services Networ. 2020. http://shenghuo.huangye88.com/xinxi/0529co6e02888a.html.

Tang V, Choy KL, Ho GTS, Lam HY, Tsang YP. An IoMT-based geriatric care management system for achieving smart health in nursing homes. Ind Manag Data Syst. 2019;119(8):1819–40.

Wang P. Embedded-based intelligent nursing home monitoring system [Master thesis]: Changchun College of Engineering. 2020.

Xie J. Research on indoor positioning algorithm and application of smart nursing home [Master thesis]: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2017.

Xiexiebang. China Information Industry “Intelligent Nursing Home System Solution”. 2019. https://www.xiexiebang.com/a5/2019051319/96e56884a89fba1e.html.

Xu L, Tuo L. Analysis and research on the management system of disabled elderly in Guangzhou smart nursing home. New Business Weekly. 2019;10:86–7.

Cui F, Ma L, Hou G, Pang Z, Hou Y, Li L. Development of smart nursing homes using systems engineering methodologies in industry 4.0. Enterprise Inf Syst. 2020;14(4):463–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17517575.2018.1536929.

SheCuiTong. Jinzhong Smart Aging Platform. 2020. http://www.kingonsoft.com:81/ylxx/zzfw/index.jhtml.

Telpo. Smart Nursing Home Intelligent Terminal. 2020. http://www.telpouc.com/Article-ndetail-id-487.html.

MHURD. Technical Standards for Intelligent Systems in Elderly Facilities (Draft for Comments): Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. 2020. http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/zqyj/201809/W020180921031507.pdf.

Liuye. Intelligent Nursing Home Management System Solution: Liuye Science and Technology, Ltd. 2020. http://www.liuyesoft.com.cn/lys/NewsInfo.asp?id=802.

Morley JE. High technology coming to a nursing home near you. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(5):409–12.

BOE. INTERIM REPORT 2018. 2018. http://file.finance.sina.com.cn/211.154.219.97:9494/MRGG/CNSESZ_STOCK/2018/2018-8/2018-08-28/4700772.PDF.

Siciliano B, Khatib O. Springer handbook of robotics. Springer; 2016.

Sun Y, Wang Y, Ai H. Research on a smart nursing home system based on an elderly helper robot. Sci Techn Vision. 2015;16:27,96.

Deng S. Smart nursing home personnel location system development [Master thesis]: University of Electronic Science and Technology. 2019.

Huang Y. Research on the key technology of intelligent nursing home control system based on deep learning [Master thesis]. North Central University. 2019.

Matusitz J, Breen GM, Wan TT. The use of eHealth services in US nursing homes as an improvement of healthcare delivery to residents. Aging Health. 2013;9(1):25–33.

Betgé-Brezetz S, Dupont MP, Ghorbel M, Kamga GB, Piekarec S. Adaptive notification framework for smart nursing home. Proceedings of the 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society: Engineering the Future of Biomedicine, EMBC 2009; 2009.

Cui F, Ma L, Hou G, Pang Z, Hou Y, Li L. Development of smart nursing homes using systems engineering methodologies in industry 4.0. Enterprise Information Systems. 2018.

Suzuki M, Yamamoto R, Ishiguro Y, Sasaki H, Kotaki H. Deep learning prediction of falls among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(6):589–94.

Fischer M, Lim YY, Lawrence E, Ganguli LK, editors. ReMoteCare: Health Monitoring with Streaming Video. 2008 7th International Conference on Mobile Business; 2008 7–8 July 2008.

Lin YJ, Su MJ, Chen HS, Lin CI, editors. A study of integrating digital health network with UPnP in an elderly nursing home. 13th IEEE Asia-Pacific Computer Systems Architecture Conference, ACSAC 2008; 2008.

Biswas J, Jayachandran M, Shue L, Gopalakrishnan K, Yap P. Design and trial deployment of a practical sleep activity pattern monitoring system. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 2009. 190–200.

Hu F, Xiao Y, Hao Q. Congestion-aware, loss-resilient bio-monitoring sensor networking for mobile health applications. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2009;27(4):450–65.

Fraile JA, Bajo J, Corchado JM, Abraham A. Applying wearable solutions in dependent environments. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2010;14(6):1459–67.

Pallikonda Rajasekaran M, Radhakrishnan S, Subbaraj P. Sensor grid applications in patient monitoring. Futur Gener Comput Syst. 2010;26(4):569–75.

Gower V, Andrich R, Braghieri P, Susi A. An advanced monitoring system for residential care facilities. Assist Techn Res Series. 2011;29:57–64.

Lee S, Kim J, Lee M. The design of the m-health service application using a Nintendo DS game console. Telemed J e-Health. 2011;17(2):124–30.

Sun Y. Human daily activity detect system optimization method using Bayesian network based on wireless sensor network. Adv Intell Soft Comput. 2011;1:721–5.

Wu M, Huang W, editors. Health care platform with safety monitoring for long-term care institutions. The 7th International Conference on Networked Computing and Advanced Information Management; 2011 21–23 June 2011.

Back I, Kallio J, Perala S, Makela K. Remote monitoring of nursing home residents using a humanoid robot. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(6):357–61.

Chang YJ, Chen CH, Lin LF, Han RP, Huang WT, Lee GC. Wireless sensor networks for vital signs monitoring: Application in a nursing home. Int J Distributed Sens Netw. 2012;2012:12.

Nijhof N, Van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC, De Jong GEN, Ankoné JW, Seydel ER. How assistive technology can support dementia care: a study about the effects of the IST Vivago watch on patients’ sleeping behavior and the care delivery process in a nursing home. Technol Disabil. 2012;24(2):103–15.

Ghorbel M, Betgé-Brezetz S, Dupont MP, Kamga GB, Piekarec S, Reerink J, et al. Multimodal notification framework for elderly and professional in a smart nursing home. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces. 2013;7(4):281–97.

Huang J, Wang T, Su T, Lan K, editors. Design and deployment of a heart rate monitoring system in a senior center. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Communications and Networking (SECON); 2013 24–27 June 2013.

Matsui T, Yoshida Y, Kagawa M, Kubota M, Kurita A. Development of a practicable non-contact bedside autonomic activation monitoring system using microwave radars and its clinical application in elderly people. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27(3):351–6.

Neuhaeuser J, D’Angelo LT. Collecting and distributing wearable sensor data: an embedded personal area network to local area network gateway server. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol So. 2013;2013:4650–3.

Pan Y. Design and implementation of a nursing home management system based on Internet of Things technology [Master thesis]: Hangzhou University of Electronic Science and Technology. 2013.

Tseng KC, Hsu CL, Chuang YH. Designing an intelligent health monitoring system and exploring user acceptance for the elderly. J Med Syst. 2013;37(6):9967.

Abbate S, Avvenuti M, Light J. Usability study of a wireless monitoring system among Alzheimer’s disease elderly population. Int J Telemed Appl. 2014;2014:617495.

Chu J, Li J, Zhu C, Yin H, Liu Z. Terminal circuit design for smart nursing home monitoring system based on wireless sensor network. Pract Electron. 2014;21:48.

Liu YW, Hsu YL. Developing a bed-centered nursing home care management system. Gerontechnology. 2014;13(2):108–9. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2014.13.02.327.00.

Zhu X, Zhou X, Chen W, Kitamura K, Nemoto T, editors. Estimation of Sleep Quality of Residents in Nursing Homes Using an Internet-Based Automatic Monitoring System. 2014 IEEE 11th Intl Conf on Ubiquitous Intelligence and Computing and 2014 IEEE 11th Intl Conf on Autonomic and Trusted Computing and 2014 IEEE 14th Intl Conf on Scalable Computing and Communications and Its Associated Workshops; 2014 9–12 Dec. 2014.

Andò B, Baglio S, Lombardo CO, Marletta V, editors. A multi-user assistive system for the user safety monitoring in care facilities. 2015 IEEE International Workshop on Measurements & Networking (M&N); 2015 12–13 Oct. 2015.

Carvalho CMA, Rodrigues CAP, Aguilar PAC, De Castro MF, Andrade RMC, Boudy J, et al., editors. Adaptive tracking model in the framework of medical nursing home using infrared sensors. 2015 IEEE Globecom Workshops, GC Wkshps 2015 – Proceedings. 2015.

Yu X, Weller P, Grattan KTV. A WSN healthcare monitoring system for elderly people in geriatric facilities. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;210:567–71.

Danielsen A. Non-intrusive bedside event recognition using infrared array and ultrasonic sensor. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 2016. 15–25.

Dias PVGF, Costa EDM, Tcheou MP, Lovisolo L. Fall detection monitoring system with position detection for elderly at indoor environments under supervision. 2016 8th IEEE Latin-American Conference on Communications, LATINCOM. 2016; 2016.

Lopez-Samaniego L, Garcia-Zapirain B. A Robot-Based Tool for Physical and Cognitive Rehabilitation of Elderly People Using Biofeedback. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(12):1176.

Ansefine KE, Muzakki, Sanudin, Anggadjaja E, Santoso H, editors. Smart and wearable technology approach for elderly monitoring in nursing home. 2017 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Social Sciences (ICETSS); 2017 7–8 Aug. 2017.

Jiang H. GPS/GSM based monitoring system for nursing homes [Master thesis]: Mudanjiang Normal College. 2017.

Mendes S, Queiroz J, Leitao P, editors. Data driven multi-agent m-health system to characterize the daily activities of elderly people. Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, CISTI; 2017.

Mendoza MB, Bergado CA, De Castro JLB, Siasat RGT, editors. Tracking system for patients with Alzheimer's disease in a nursing home. IEEE Region 10 Annual International Conference, Proceedings/TENCON. 2017.

Montanini L, Raffaeli L, de Santis A, del Campo A, Chiatti C, Paciello L, et al. Supporting caregivers in nursing homes for Alzheimer’s disease patients: A technological approach to overnight supervision. Communications in Computer and Information Science. 2017. 1–19.

Saod AHM, Ghani SJAM, Harron NA, Ramlan SA, Rashid ANA, Ishak NH, editors. Android-based elderly support system. 2017 IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE); 2017 24–25 April 2017.

Singh D, Kropf J, Hanke S, Holzinger A. Ambient assisted living technologies from the perspectives of older people and professionals. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 2017. 255–66.

Wu Y, Liu L, Kang J, Li L, Huang B. Measuring the wellness indices of the elderly using RFID sensors data in a smart nursing home. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 2017. 66–73.

Bleda AL, Maestre R, Beteta MA, Vidal JA, editors. AmICare: Ambient Intelligent and Assistive System for Caregivers Support. Proceedings - 16th International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing, EUC 2018. 2018.

Donnelly S, Reginatto B, Kearns O, Mc Carthy M, Byrom B, Muehlhausen W, et al. The Burden of a Remote Trial in a Nursing Home Setting: Qualitative Study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e220.

Mahfuz S, Isah H, Zulkernine F, Nicholls P, editors. Detecting Irregular Patterns in IoT Streaming Data for Fall Detection. 2018 IEEE 9th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON); 2018 1–3 Nov. 2018.

Morita T, Taki K, Fujimoto M, Suwa H, Arakawa Y, Yasumoto K, editors. BLE Beacon-based Activity Monitoring System toward Automatic Generation of Daily Report. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, PerCom Workshops 2018. 2018.

Wu Y, Liu L, Li L, Lu M, Li L. Determining senior wellness status using an intelligent system based on wireless sensor network and bioinformation. Web Intelligence. 2018;16(3):159–66.

Borelli E, Paolini G, Antoniazzi F, Barbiroli M, Benassi F, Chesani F, et al. HABITAT: An IoT solution for independent elderly. Sensors (Switzerland). 2019;19(5):1258.

Cai C, Wang P. Research on fall posture detection for the elderly. J Changchun College Engineering (Natural Science Edition). 2019;20(04):29–34.

Delmastro F, Dolciotti C, La Rosa D, Di Martino F, Magrini M, Coscetti S, et al. Experimenting mobile and e-health services with frail MCI older people. Information (Switzerland). 2019;10(8).

Fong ACM, Fong B, Hong G, editors. Short-range tracking using smart clothing sensors : AA case study of using low power wireless sensors for pateints tracking in a nursing home setting. 2018 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Communication and Information Systems, ICCIS 2018; 2019.

Ghosh N, Maity S, Maity K, Saha S, editors. Non-Parametric Learning Technique for Activity Recognition in Elderly Patients. TENCON 2019 - 2019 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON); 2019 17–20 Oct. 2019.

Lenoir J. Effective User Interface of IoT System at Nursing Homes. Communication Comput Inform Sci. 2019;490–8.

Shen M. IoT technology based management system for nursing homes. Comput Prod Distrib. 2019;5(8):122.

Takahashi K, Kitamura K, Nishida Y, Mizoguchi H, editors. Battery-less shoe-type wearable location sensor system for monitoring people with dementia. Proceedings of the International Conference on Sensing Technology, ICST. 2019.

Toda K, Shinomiya N. Machine learning-based fall detection system for the elderly using passive RFID sensor tags. Proceedings of the International Conference on Sensing Technology, ICST. 2019.

Xiao B. Analysis and application of smart mattress-based elderly care monitoring data [Master thesis]: Tung Wah University. 2019.

Yoo B, Muralidharan S, Lee C, Lee J, Ko H, editors. KLog-Home: A holistic approach of in-situ monitoring in elderly-care home. Proceedings - 22nd IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering and 17th IEEE International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing, CSE/EUC 2019; 2019.

Buisseret F, Catinus L, Grenard R, Jojczyk L, Fievez D, Barvaux V, et al. Timed Up and Go and Six-Minute Walking Tests with Wearable Inertial Sensor: One Step Further for the Prediction of the Risk of Fall in Elderly Nursing Home People. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;20(11):3207.

Chen W, Wang X, Chen J, Ding Z, Li J, Li B. An Alarm System Based on BP Neural Network Algorithm for the Detection of Falls to Elderly Person. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST2021. p. 571–81.

Gharti P, editor A study of fall detection monitoring system for elderly people through IOT and mobile based application devices in indoor environment. 2020 5th International Conference on Innovative Technologies in Intelligent Systems and Industrial Applications (CITISIA); 2020 25–27 Nov. 2020.

Lanza F, Seidita V, Chella A. Agents and robots for collaborating and supporting physicians in healthcare scenarios. J Biomed Inform. 2020;108:103483.

Lee SK, Ahn J, Shin JH, Lee JY. Application of Machine Learning Methods in Nursing Home Research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6234.

Mishkhal I, Sarah Abd ALK, Hassan Hadi S, Alqayyar A. Deep Learning with network of Wearable sensors for preventing the Risk of Falls for Older People. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;928(3).

Wan HC, Chin KS. Exploring internet of healthcare things for establishing an integrated care link system in the healthcare industry. Int J Eng Business Manage. 2021;13.

Chen IH, Chen CH, Ting YC, Hung WL, Cheng BY. The Guardian Slippers: Designing an IoT Device to Enhance Safety for the Elderly in the Nursing Home. Lect Notes Netw Syst. 2021;263:369–77.

Flores-Martin D, Rojo J, Moguel E, Berrocal J, Murillo JM. Smart Nursing Homes: Self-Management Architecture Based on IoT and Machine Learning for Rural Areas. Wireless Commun Mobile Comput. 2021;2021.

Chan WM, Woo J, Hui E, Hjelm NM. The role of telenursing in the provision of geriatric outreach services to residential homes in Hong Kong. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(1):38–46.

Pallawala P, Lun K. EMR based telegeriatric system. Int J Med Inform. 2001;61(2–3):229–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1386-5056(01)00144-7.

Weiner M, Schadow G, Lindbergh D, Warvel J, Abernathy G, Dexter P, et al. Secure Internet video conferencing for assessing acute medical problems in a nursing facility. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:751–5.

Hui E, Woo J. Telehealth for older patients: the Hong Kong experience. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;83(8 Suppl 3):39–41.

Savenstedt S, Bucht G, Norberg L, Sandman PO. Nurse-doctor interaction in teleconsultations between a hospital and a geriatric nursing home. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(1):11–8.

Weiner M, Schadow G, Lindbergh D, Warvel J, Abernathy G, Perkins SM, et al. Clinicians’ and patients’ experiences and satisfaction with unscheduled, nighttime, Internet-based video conferencing for assessing acute medical problems in a nursing facility. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:709–13.

Zelickson BD. Teledermatology in the nursing home. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;32:167–71.

Armer JM, Harris K, Dusold JM. Application of the Concerns-Based Adoption Model to the installation of telemedicine in a rural Missouri nursing home. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2004;20(1):42–9.

Savenstedt S, Zingmark K, Sandman PO. Being present in a distant room: aspects of teleconsultations with older people in a nursing home. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(8):1046–57.

Daly JM, Jogerst G, Park JY, Kang YD, Bae T. A nursing home telehealth system: keeping residents connected. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(8):46–51.

Lavanya J, Goh KW, Leow YH, Chio MT, Prabaharan K, Kim E, et al. Distributed personal health information management system for dermatology at the homes for senior citizens. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;2006:6312–5.

Loeb MB, Carusone SB, Marrie TJ, Brazil K, Krueger P, Lohfeld L, et al. Interobserver reliability of radiologists’ interpretations of mobile chest radiographs for nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(7):416–9.

Shulman B, Conn DK, Elford R. Geriatric telepsychiatry and telemedicine: a literature review. Can J Geriatr. 2006;9(4):139–46.

Cusack CM, Pan E, Hook JM, Vincent A, Kaelber DC, Middleton B. The value proposition in the widespread use of telehealth. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(4):167–8.

Janardhanan L, Leow YH, Chio MT, Kim Y, Soh CB. Experience with the implementation of a web-based teledermatology system in a nursing home in Singapore. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(8):404–9.

Biglan KM, Voss TS, Deuel LM, Miller D, Eason S, Fagnano M, et al. Telemedicine for the care of nursing home residents with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(7):1073–6.

Chang JY, Chen LK, Chang CC. Perspectives and expectations for telemedicine opportunities from families of nursing home residents and caregivers in nursing homes. Int J Med Informatics. 2009;78(7):494–502.

Qadri S, Wang J, Ruiz J, Roos B. Personal digital assistants as point-of-care tools in long-term care facilities: a pilot study. Educ Gerontol. 2009;35(4):294–307.

Chang HL, Shaw MJ, Lai F, Ko WJ, Ho YL, Chen HS, et al. U-Health: an example of a high-quality individualized healthcare service. Pers Med. 2010;7(6):677–87.

Rabinowitz T, Murphy KM, Amour JL, Ricci MA, Caputo MP, Newhouse PA. Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):34–40.

Wälivaara BM, Andersson S, Axelsson K. General practitioners’ reasoning about using mobile distance-spanning technology in home care and in nursing home care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(1):117–25.

Eklund K, Klefsgard R, Ivarsson B, Geijer M. Positive experience of a mobile radiography service in nursing homes. Gerontology. 2012;58(2):107–11.

Gray LC, Edirippulige S, Smith AC, Beattie E, Theodoros D, Russell T, et al. Telehealth for nursing homes: the utilization of specialist services for residential care. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(3):142–6.

Handler SM, Boyce RD, Ligons FM, Perera S, Nace DA, Hochheiser H. Use and perceived benefits of mobile devices by physicians in preventing adverse drug events in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):906–10.

Novak L, Walker S, Fonda S, Schmidt V, Vigersky R. The impact of a video phone reminder system on glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a retirement home. Diabetes. 2013;62:A217.

Vowden K, Vowden P. A pilot study on the potential of remote support to enhance wound care for nursing-home patients. J Wound Care. 2013;22(9):481–8.

Catic AG, Mattison ML, Bakaev I, Morgan M, Monti SM, Lipsitz L. ECHO-AGE: an innovative model of geriatric care for long-term care residents with dementia and behavioral issues. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):938–42.

Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ. Use of telemedicine can reduce hospitalizations of nursing home residents and generate savings for medicare. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2014;33(2):244–50.

Crotty M, Killington M, van den Berg M, Morris C, Taylor A, Carati C. Telerehabilitation for older people using off-the-shelf applications: acceptability and feasibility. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20(7):370–6.

Doumbouya MB, Kamsu-Foguem B, Kenfack H, Foguem C. Combining conceptual graphs and argumentation for aiding in the teleexpertise. Comput Biol Med. 2015;63:157–68.

Huang F, Chang P, Hou IC, Tu MH, Lan CF. Use of a mobile device by nursing home residents for long-term care comprehensive geriatric self-assessment: a feasibility study. CIN - Comput Inform Nurs. 2015;33(1):28–36.

Montalto M, Shay S, Le A. Evaluation of a mobile X-ray service for elderly residents of residential aged care facilities. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(5):517–21.

Toh HJ, Chia J, Koh E, Lam K, Magpantay GC, De Leon CM, et al. Increased engagement in telegeriatrics reduces unnecessary hospital admissions of nursing home residents. Communication Comput Inform Sci. 2015;578:81–90.

Toh HJ, Chia J, Koh E, Lam K, Magpantay GC, De Leon CM, et al., editors. User perceptions of the telemedicine programme in nursing homes the Singapore perspective. ICT4AgeingWell 2015 - Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health. 2015.

Volicer L. Nursing home telepsychiatry. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(1):7–8.

De Luca R, Bramanti A, De Cola MC, Trifiletti A, Tomasello P, Torrisi M, et al. Tele-health-care in the elderly living in nursing home: the first Sicilian multimodal approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(4):753–9.

Dozet A, Ivarsson B, Eklund K, Klefsgard R, Geijer M. Radiography on wheels arrives to nursing homes - an economic assessment of a new health care technology in southern Sweden. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(6):990–7.

Driessen J, Bonhomme A, Chang W, Nace DA, Kavalieratos D, Perera S, et al. Nursing home provider perceptions of telemedicine for reducing potentially avoidable hospitalizations. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(6):519–24.

Gaglio G, Lewkowicz M, Tixier M, editors. "It is not because you have tools that you must use them" The difficult domestication of a telemedicine toolkit to manage emergencies in nursing homes. Proceedings of the International ACM SIGGROUP Conference on Supporting Group Work. 2016.

Gillespie SM, Shah MN, Wasserman EB, Wood NE, Wang H, Noyes K, et al. Reducing emergency department utilization through engagement in telemedicine by senior living communities. Telemed e-Health. 2016;22(6):489–96.

Morley JE. Telemedicine: coming to nursing homes in the near future. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(1):1–3.

Schneider R, Dorsey ER, Biglan K. Telemedicine care for nursing home residents with Parkinsonism. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):218–20.

Kjelle E, Lysdahl KB. Mobile radiography services in nursing homes: a systematic review of residents’ and societal outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):231.

Newbould L, Mountain G, Hawley M, Ariss S. Remote health care provision in care homes. Stud Health Tech Inform. 2017;242:148–51.

Queyroux A, Saricassapian B, Herzog D, Muller K, Herafa I, Ducoux D, et al. Accuracy of teledentistry for diagnosing dental pathology using direct examination as a gold standard: results of the Tel-e-dent study of older adults living in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(6):528–32.

Delmastro F, Dolciotti C, Palumbo F, Magrini M, Di Martino F, La Rosa D, et al., editors. Long-term care: How to improve the quality of life with mobile and e-health services. International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications; 2018.

Kjelle E, Lysdahl KB, Olerud HM, Myklebust AM. Managers’ experience of success criteria and barriers to implementing mobile radiography services in nursing homes in Norway: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):301.

Esteves M, Esteves M, Abelha A, Machado J, editors. A mobile health application to assist health professionals: A case study in a Portuguese nursing home. ICT4AWE 2019 - Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health; 2019.

Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):109–27.

Ozkaynak M, Reeder B, Drake C, Ferrarone P, Trautner B, Wald H, et al. Characterizing workflow to inform clinical decision support systems in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):1024–33.

Shafiee Hanjani L, Peel NM, Freeman CR, Gray LC. Using telehealth to enable collaboration of pharmacists and geriatricians in residential medication management reviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(5):1256–61.

Cormi C, Chrusciel J, Laplanche D, Dramé M, Sanchez S. Telemedicine in nursing homes during the COVID-19 outbreak: a star is born (again). Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(6):646–7.

Lai KY, Pathipati MP, Blumenkranz MS, Leung LS, Moshfeghi DM, Toy BC, et al. Assessment of eye disease and visual impairment in the nursing home population using mobile health technology. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020;51(5):262–70.

Low JA, Toh HJ, Tan LLC, Chia JWK, Soek ATS. The Nuts and Bolts of Utilizing Telemedicine in Nursing Homes - The GeriCare@North Experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(8):1073–8.

Ohligs M, Stocklassa S, Rossaint R, Czaplik M, Follmann A. Employment of telemedicine in nursing homes: clinical requirement analysis, system development and first test results. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:1427–37.

Alexander GL, Powell KR, Deroche CB. An evaluation of telehealth expansion in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(2):342–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa253.

Okamoto L, Okamoto L, Uechi M, Blanchette P, von Preyss-Friedman S. Renaissance in the nursing home during the COVID-19 pandemic: telemedicine blooms in a time of crisis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(3):B16.

Lenderink BW, Egberts TC. Closing the loop of the medication use process using electronic medication administration registration. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(4):185–90.

Alexander GL. Human factors, automation, and alerting mechanisms in nursing home electronic health records [Ph.D.]. Ann Arbor: University of Missouri - Columbia; 2005.

Byrne CM. Impact of prospective computerized clinical decision support information and targeted assistance on nursing home resident outcomes [Ph.D.]. Ann Arbor: State University of New York at Albany; 2005.

Celler BG, Basilakis J, Budge M, Lovel NH. A clinical monitoring and management system for residential aged care facilities. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;2006:3301–4.

Cherry BJ. Determining facilitators and barriers to adoption of electronic health records in long -term care facilities [D.N.Sc.]. Ann Arbor: The University of Tennessee Health Science Center; 2006.

Alexander GL, Rantz M, Flesner M, Diekemper M, Siem C. Clinical information systems in nursing homes: an evaluation of initial implementation strategies. CIN Comput Informa Nurs. 2007;25(4):189–97.

Alexander GL. A descriptive analysis of a nursing home clinical information system with decision support. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2008;5:12.

Breen GM, Zhang NJ. Introducing ehealth to nursing homes: theoretical analysis of improving resident care. J Med Syst. 2008;32(2):187–92.

Yu P, Hailey D, Li H. Caregivers’ acceptance of electronic documentation in nursing homes. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14(5):261–5.

Sax C, Lawrence E, editors. Point-of-treatment: Touchable e-nursing user interface for medical emergencies. 2009 Third International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies. IEEE; 2009.

Scott-Cawiezell J, Madsen RW, Pepper GA, Vogelsmeier A, Petroski G, Zellmer D. Medication safety teams’ guided implementation of electronic medication administration records in five nursing homes. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(1):29–35.

Ohol RR. Web Based Nursing Home Information System: Needs, Benefits, and Success in Providing Efficient Care at Long Term Care Facilities [M.S.]. Ann Arbor: University of Missouri - Columbia; 2010.

Alexander GL, Rantz M, Galambos C, Vogelsmeier A, Flesner M, Popejoy L, et al. Preparing nursing homes for the future of health information exchange. Appl Clin Inform. 2015;6(2):248–66.

Huang Z, Chen Z, Liu Z. Smart nursing home integrated management system design. Electronic Sci Tech. 2015;28(11):132–4.

Wang Y. The, “Internet of Things” makes pension records intelligent. Landai World. 2016;S2:103–4.

Zhang C. Research on the design of health management services for nursing homes [Master thesis]: Jiangnan University. 2017.

Xie X. Research and implementation of a smart care management system for the elderly [Master thesis]: Guangdong University of Technology. 2016.

Ausserhofer D, Favez L, Simon M, Zúñiga F. Electronic health record use in Swiss nursing homes and its association with implicit rationing of nursing care documentation: multicenter cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(3):e22974.

Kei Hong S, Ting CW, Chui PL, Teddy Tai-Ning L, Sau Chu C, Cheung YT. Medication Management Service for Old Age Homes in Hong Kong Using Information Technology, Automation Technology, and the Internet of Things: Pre-Post Interventional Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(2):e24280.

Masuda S, Numao M, editors. Sensor-based detection of invisible changes in activities towards visualizing disuse syndrome. AAAI Spring Symposium - Technical Report; 2017.

González I, Navarro FJ, Fontecha J, Cabañero-Gómez L, Hervás R. An Internet of Things infrastructure for gait characterization in assisted living environments and its application in the discovery of associations between frailty and cognition. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks. 2019;15(10).

Kokubo R, Kamiya Y, editors. A novel period estimation method for periodic signals suitable for vital sensing. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. 2019.

Ambagtsheer RC, Shafiabady N, Dent E, Seiboth C, Beilby J. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to identify frailty within a residential aged care administrative data set. Int J Med Inform. 2020;136:104094.

Hsu WC, Kuo CW, Chang WW, Chang JJ, Hou YT, Lan YC, et al., editors. A WSN smart medication system. Proc Eng. 2010;5:588–91.

Chang WW, Sung TJ, Huang HW, Hsu WC, Kuo CW, Chang JJ, et al. A smart medication system using wireless sensor network technologies. Sens Actuators, A. 2011;172(1):315–21.

Tsai HL, Tseng CH, Wang LC, Juang FS, editors. Bidirectional smart pill box monitored through internet and receiving reminding message from remote relatives. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Taiwan, ICCE-TW 2017; 2017.

Delmastro F, Dolciotti C, Palumbo F, Magrini M, Di Martino F, La Rosa D, et al., editors. Long-term care: how to improve the quality of life with mobile and e-health services. 2018 14th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob). IEEE; 2018.