Abstract

Background

Burnout is a growing problem in medical education, and is usually characterised by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy. Currently, the majority of burnout studies have been conducted in western high-income countries, overshadowing findings from low- and middle-income countries. Our objective is to investigate burnout and its associated predictive factors in Morocco, aiming to guide intervention strategies, while also assessing differences between the preclinical and clinical years.

Methods

A cross-sectional, self-administered online survey assessing burnout dimensions and its main determinants was distributed among medical students at Université Mohammed VI des Sciences et de la Santé (UM6SS, Casablanca, Morocco). Descriptive analyses involved computing mean scores, standard deviations and Pearson correlations. Further, t-tests were performed to check for significant differences in burnout dimensions across the preclinical and clinical learning phase, and stepwise linear regression analyses were conducted using a backward elimination method to estimate the effects of the selected variables on the three burnout dimensions.

Results

A t-test assessing the difference in cynicism found a significant difference between students at the preclinical phase and the clinical phase, t(90) = -2.5, p = 0.01. For emotional exhaustion and reduced professional efficacy no significant difference was observed. A linear regression analysis showed that emotional exhaustion was significantly predicted by workload, work-home conflict, social support from peers and neuroticism. Cynicism was predicted by the learning phase, workload, meaningfulness and neuroticism; and reduced professional efficacy by neuroticism only.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a potential gradual increase in cynicism during medical education in Morocco. Conducting this study in a low- and middle income country has enhanced the scientific understanding of burnout in these regions. Given the identified predictive factors for burnout, such as workload, work-home conflict, support from peers, neuroticism, and meaningfulness, it is necessary to focus on these elements when developing burnout interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

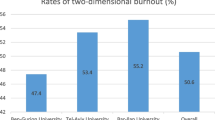

According to recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, medical students are highly susceptible to burnout [3, 16, 18, 20]. Almutairi et al. [3] estimated a prevalence rate of 37.2% [CI 95%, 32.66—42.05%], and Frajerman et al. [20] reported a prevalence of 44.2% [CI 95%, 33.4 – 55.0%]. Furthermore, Dyrbye et al. [16] noted a significantly higher burnout prevalence (p < 0.001) among medical students compared to the general population [16]. In addition, a study by Brazeau et al. [10] found that incoming medical students exhibit a lower burnout prevalence compared to non-medical peers, suggesting that the educational process may negatively influence burnout prevalence among medical students.

Burnout is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon resulting from prolonged periods of stress, and is usually defined in literature by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy [34, 35]. Emotional exhaustion entails persistent physical and emotional fatigue [35]. Cynicism refers to the detached attitude towards one’s work, and reduced professional efficacy signifies the diminishing belief in one’s competence [35].

Burnout has often been studied in the framework of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model, which underlines the importance of job demands and job resources that contribute to burnout in a certain occupational group [5, 14]. The same framework can be applied to educational groups, such as medical students, as an education also consists of various study demands (such as workload) and study resources (such as social support from supervisor) [1, 15, 22, 29, 31, 49]. In addition, Robins et al. [43] found that high levels of emotional exhaustion and cynicism in the educational setting are predictive of future exhaustion and cynicism at work, demonstrating the importance of burnout interventions in the university context [43].

Various study demands and resources have been linked to burnout, and we have focused on those with the most substantial evidence. The main study demands identified are workload, emotional demands, and work-home conflict [22, 28]. On the other hand, key study resources or protective factors include meaningfulness, social support from peers and social support from supervisors [22, 28]. Additionally, certain individual traits have also been associated with higher burnout scores, with neuroticism and perfectionism showing the strongest evidence [4, 9, 21].

In addition to study demands, study resources and individual traits; evidence shows that socio-economic and cultural factors can also influence burnout, and these factors can play a moderating role for the associations within the JD-R Model [17, 23, 32, 42]. In various countries, but particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), overburdened healthcare systems and limited career prospects increase burnout prevalence, exacerbating the already critical shortage of healthcare workers and encouraging individuals to emigrate and intensifying the “brain drain” [50, 51].

Further, studies have shown that cultural factors may play a role in predicting or moderating burnout, such as collectivistic versus individualistic or masculine versus feminine cultures [2, 32, 42]. For example, a collectivist society (i.e. the interest of the group prevails over the individual) might protect against burnout due to the importance of a strong social network that buffers burnout, while a masculine country (i.e. more focus on competitiveness) might result in greater reluctance to talk about mental health or ask for professional help, as it could be perceived as a sign of weakness [32].

Currently, the majority of burnout studies have been conducted in western high-income countries (HICs), overshadowing findings from non-western LMICs [17, 23]. Although initial evidence suggests a similar high burnout prevalence in LMICs compared to HICs, the key factors predicting burnout in these regions may differ, which emphasizes the need for more comprehensive insights from these areas [17, 23].

Morocco, a North African Arab country classified as an LMIC by the World Bank [48], has seen limited research into burnout [17, 23]. For instance, a recent systematic review by Kaggwa et al. [23] on burnout prevalence among university students in LMICs found no research from Morocco that met their inclusion criteria. Similarly, a systematic review by Elbarazi et al. [17] on burnout among healthcare workers found no Moroccan studies that met their inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the majority of existing burnout studies conducted in Morocco have focused on healthcare workers [17, 24] or residents [8], instead of medical students. In addition, previous studies have mainly reported prevalence rates of burnout without incorporating factors that predict the likelihood of burnout [27, 30].

To address the above research gaps, this study aims to assess burnout in Morocco, a LMIC, and to explore its associations with sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, gender, learning phase), individual traits (e.g., neuroticism), study demands (e.g., workload) and study resources (e.g., social support). There is a need for research in LMICs that explores these associations, with the aim of guiding intervention strategies tailored to this particular context [17, 23, 27].

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional, self-administered online survey was distributed among medical students at Université Mohammed VI des Sciences et de la Santé (UM6SS, Casablanca, Morocco) across preclinical (first and second year) and clinical phases (third to seventh grade) between November and December 2022. A convenience sampling strategy was applied, where the faculty of medicine and various year representatives facilitated survey distribution through school mail and WhatsApp groups. The survey was administered in French via Qualtrics software [40].

Study population

The study population encompassed approximately 318 first-year, 382 s-year, 340 third-year, 324 fourth-year, 235 fifth-year, 226 sixth-year, and 213 seventh-year students, totalling 2038 students. The inclusion criteria comprised individuals who were at least 18 years old, French-speaking, and enrolled as medical students at UM6SS in Casablanca, Morocco. Respondents received information on the study’s objectives via an informational letter, and their participation was always anonymous and voluntary.

Data collection

“Burnout” was measured using the French version of the 15-item Maslach Burnout Inventory – Student Survey (MBI-SS) [19]. This widely accepted instrument measures burnout across its three core dimensions: emotional exhaustion (five items), cynicism (four items), and reduced professional efficacy (6 items) [34]. Respondents rated the frequency of their experiences using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from "never" (0) to "every day" (6). The internal consistency, measured by Cronbach's alpha, was 0.88 for emotional exhaustion, 0.80 for cynicism, and 0.78 for professional efficacy.

With regard to study demands, “Workload” (four items), “Emotional Demands” (three items) and “Work-Home Conflict” (four items) were measured using corresponding scales from the French Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ; [12]). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “never” (0) to “always” (4). “Workload” achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73, “Emotional Demands” had 0.76, and “Work-Home Conflict” scored 0.87. With regard to study resources, “Meaningfulness” (two items), “Social Support from Peers” (three items), and "Social Support from Supervisor” (three items) were assessed using the corresponding scales from the French COPSOQ [12]. Items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “never” (0) to “always” (4). The Cronbach’s alphas were high for all scales: “Meaningfulness” had 0.79, “Social Support from Peers” 0.79, and "Social Support from Supervisor” scored 0.83.

In addition, we assessed “Perfectionism” (8 items) using the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS) [11], and measured “Neuroticism” (3 items) with the neuroticism scale from the Big Five Inventory-Extra Short Form (BFI-XS) [47], both employing a 5-point Likert scale from “totally disagree” (1) to “totally agree” (5). The French versions were obtained via back-translation [33]. Perfectionism demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, while neuroticism achieved 0.72. Finally, we controlled for age and gender due to their potential influence on burnout [3, 49, 51].

Statistical analysis

All analyses and visualisations were performed in R, version 4.3.0 [41]. We tested the assumptions of linear regression and when assumptions were violated, appropriate procedures were applied. Descriptive analyses involved computing mean scores and standard deviations. T-tests were conducted to check for significant differences between emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy across the preclinical and clinical learning phase. We also conducted three stepwise linear regression analyses using a backward elimination method to estimate the effect of the different selected variables (i.e., workload, work-home conflict, emotional demands, meaningfulness, social support from peers, social support from your supervisor, neuroticism and perfectionism) on each burnout dimension as the dependent variable [25]. All independent variables were entered into the model initially and were successively removed if p > 0.10 until a final model was produced [13].

Ethical approval & informed consent

This study was carried out according to the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects of the Declaration of Helsinki. More specifically, the overall WeMeds study was approved by the Ethics Committee Research UZ/KU Leuven in April 2021 (S64150). Also, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of Moulay Ismail University of Meknes (N° CERB10/22) to conduct this study in Morocco. All participants had to provide signed informed consent before participation.

Results

Sociodemographic and general information of participants

In total, 92 medical students were included in this study, resulting in a response rate of 5% (i.e., 92/2083). The mean age of the respondents was 20.43 years (SD = 2.32). In addition, 78% of our respondents were female, 51% were in the preclinical learning phase, 96% reported being single, none of the participants indicated having children and 68% reported living together with someone (i.e. friends, partner, parents, or grandparents) (Table 1).

Descriptive results

Supplementary Table S.1 displays the means and standard deviations for all variables, as well as the reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha in parentheses) and Pearson’s correlations for the dependent and independent variables. Figure 1 displays a correlation plot, developed in R and visualizing the correlations between all study variables that have a p-value of maximum 0.05 to judge statistical significance, and a correlation coefficient equal to or greater than 0.30 [36].

Differences in emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced professional efficacy between clinical and preclinical medical students

A t-test assessing the difference in emotional exhaustion found no significant results between students at preclinical (M = 3.09, SD = 1.50) and clinical learning phases (M = 3.25, SD = 1.40); t(90) = -0.51, p = 0.60. Conversely, a significant difference was identified for cynicism, with students in the clinical phase (M = 2.39, SD = 1.41) demonstrating higher levels compared to those in the preclinical phase (M = 1.66, SD = 1.47); t(90) = -2.5, p = 0.01. Regarding professional efficacy, no statistical significance was observed between preclinical (M = 3.56, SD = 1.28) and clinical students (M = 3.21, SD = 0.93), t(79) = 0.94, p = 0.4.

Linear regression

Emotional exhaustion

The results of the stepwise regression are presented in Table 2, and show that four predictors (workload, work-home conflict, support from peers, and neuroticism) explained 58.4% of the variance (R2 = 0.584, F (4,87) = 30.5, p < 0.001). Higher levels of workload, work-home conflict, and neuroticism were found to significantly predict higher emotional exhaustion scores, while lower levels of peer support also significantly contributed to increased emotional exhaustion. The adjusted R2 was found to be 0.564.

Cynicism

The results of the stepwise regression with backward elimination for the dependent variable cynicism are presented in Table 3, and indicate that four predictors (learning phase, workload, meaningfulness and neuroticism) explained 45.7% of the variance (R2 = 0.457, F (4, 87) = 18.3, p < 0.001). It was found that the clinical learning phase, higher workload, higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of meaningfulness predicted higher cynicism scores. The adjusted R2 was found to be 0.432.

Professional efficacy

The results of stepwise regression with backward elimination for the dependent variable professional efficacy are shown in Table 4, and indicate that only one predictor, neuroticism, explained 20.8% of the variance (R2 = 0.208, F (1, 90) = 23.7, p < 0.001). It was found that higher levels of neuroticism predicted lower levels of professional efficacy. The adjusted R2 was 0.2.

Discussion

Our study assessed burnout in Morocco and explored its associations with sociodemographic factors, individual traits, study demands and study resources. By conducting this study in a low- and middle income country, we enhanced the scientific knowledge of burnout in these regions and identified key predictive factors. These findings can serve as focus points for the design and implementations of targeted interventions.

Increased levels of cynicism

A significant difference for cynicism was found between clinical and preclinical students, where clinical students exhibited higher scores. No significant differences were found for emotional exhaustion and professional efficacy between these two groups. Consequently, our results suggest a gradual increase in cynicism during medical education, which was confirmed by previous studies [26, 37, 49]. For instance, Kilic et al. [26] observed increasing cynicism as the educational career progressed, while emotional exhaustion was highest at critical graduation moments. Interestingly, emotional exhaustion, which occurs when people feel overwhelmed, is closely related to absenteeism, while cynicism is the burnout dimension most strongly associated with turnover intentions [7].

Primary study demands and resources

Furthermore, our analysis showed that emotional exhaustion was significantly predicted by two study demands (i.e. workload, and work-home conflict) and one study resource (i.e. social support from peers). Cynicism was predicted by the learning phase, study demand workload and study resource meaningfulness. Professional efficacy was not predicted by any study demand or resource. These findings are consistent with previous studies [20, 39, 44, 49]. For example, despite deriving meaning from their work, physicians are often unsatisfied with the excessive workload, affecting their work-home balance [45]. Among the study demands and resources examined, study demands demonstrated a stronger relationship with burnout compared to study resources. This finding is consistent with previous studies on the JD-R model, which have reported that study demands tend to be more closely linked with burnout, whereas study resources are more strongly linked to work engagement and less to burnout [6, 14, 35].

Neuroticism as the main predictive individual trait of burnout

Our study has shown that neuroticism played an important predictive role in all three burnout dimensions, which is in line with previous studies [4, 9, 38]. For instance, Bianchi [9] explained that in their study, neuroticism accounted for a substantial portion of the variance in burnout, exceeding the influence of work stress and social support. Additionally, previous studies have specifically linked neuroticism to emotional exhaustion [46], while others have identified indirect effects of neuroticism on burnout, mediated through psychological and academic distress [52].

Socio-economic and cultural factors

Finally, this study has provided preliminary evidence suggesting both similarities and differences in the assessment of burnout in one LMIC compared to previous studies. It is recommended that future studies incorporate specific contextual factors relevant to this setting. For instance, in collectivist countries, the inclusion of social support from family and friends is crucial, while considerations such as frustrations with career prospects, emigration plans, or financial limitations are pertinent for LMICs [50, 51]. The cultural dimension of masculinity is also important to consider, as high levels of masculinity are associated with a greater reluctance to acknowledge mental health issues or seek professional help [2, 32]. Moreover, countries with a pronounced hierarchical structure may be characterized by a substantial power distance between students and supervisors, potentially hindering students from seeking assistance [2, 32].

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of this research lies in the data collection conducted within a LMIC, a context that has received limited attention with regard to burnout research. Furthermore, our findings provide valuable insights that offer a foundation for the generation of new research questions or formulation of new hypotheses. Nevertheless, we should also note several limitations of our research. In first instance, the sample size was rather small (n = 92), despite our continuous recruitment efforts. Future research should aim for more participants, especially when making subgroup comparisons (i.e. preclinical and clinical phase). In addition, the potential stigma to talk about mental health issues should be considered during recruitment strategies. Further, our study had a cross-sectional design, which constrains the conclusions that can be drawn. A longitudinal study could have revealed changes over time, reducing cohort effects and providing more comprehensive information. Additionally, the incorporated validated questionnaires (i.e., MBI, COPSOQ) relied on self-reports, which are prone to social desirability bias. Moreover, it is important to note that our analyses do not clinically diagnose burnout, but measure burnout on a continuum, ranging from low to high burnout on the three dimensions. In addition, because previous studies have argued against using cutoff scores for burnout or relying on a single burnout score based on the MBI, we focused this study on the three separate burnout dimensions instead. Next, respondents participated voluntarily, implying the possibility of selection bias, as those who chose to participate may possess distinct characteristics setting them apart from non-participants (e.g., interested in mental health or burnout experience). Finally, our study was a single-centre study, with surveys administered exclusively at one private university. Although our findings may be generalizable to other universities with similar characteristics, their comparability to different settings may be limited.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a potential gradual increase in cynicism during medical education in Morocco. Conducting this study in a low- and middle income country has enhanced the scientific understanding of burnout in these regions. Given the identified predictive factors for burnout, such as workload, work-home conflict, neuroticism, social support from peers and meaningfulness, it is necessary to focus on these elements when developing burnout interventions.

Abbreviations

- BFI-XS:

-

Big Five Inventory-Extra Short

- COPSOQ:

-

Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire

- FMPS:

-

Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale

- HIC:

-

High income country

- JD-R:

-

Job Demands – Resources

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle income country

- M:

-

Mean

- MBI-SS:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory – Student Survey

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- UM6SS:

-

Université Mohammed VI des Sciences et de la Santé

References

Abreu Alves S, Sinval J, Lucas Neto L, Marôco J, Gonçalves Ferreira A, Oliveira P. Burnout and dropout intention in medical students: the protective role of academic engagement. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03094-9.

Al-Alawi AI, Alkhodari HJ. Cross-cultural Differences in Managing Businesses: Applying Hofstede Cultural Analysis in Germany, Canada, South Korea and Morocco. Elixir Int Bus Manage. 2016;95(June):40855–61.

Almutairi H, Alsubaiei A, Abduljawad S, Alshatti A, Fekih-Romdhane F, Husni M, Jahrami H. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640221106691.

Angelini G. Big five model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01056-y.

Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J Manag Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev Int. 2008;13(3):209–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476.

Bang H, Reio TG. Examining the role of cynicism in the relationships between burnout and employee behavior. Revista de Psicologia Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones. 2017;33(3):217–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2017.07.002.

Belayachi J, Rkain I, Rkain H, Madani N, Amlaiky F, Zekraoui A, Dendane T, Abidi K, Zeggwagh AA, Abouqal R. Burnout syndrome in Moroccan Training Residents: Impact on Quality of Life. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(2):260–1.

Bianchi R. Burnout is more strongly linked to neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270(May):901–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.015.

Brazeau CMLR, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, Massie FS, Eacker A, Moutier C, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Dyrbye LN. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000482.

Burgess AM, Frost RO, DiBartolo PM. Development and Validation of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale-Brief. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2016;34(7):620–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916651359.

Burr H, Berthelsen H, Moncada S, Nübling M, Dupret E, Demiral Y, Oudyk J, Kristensen TS, Llorens C, Navarro A, Lincke HJ, Bocéréan C, Sahan C, Smith P, Pohrt A. The Third Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Saf Health Work. 2019;10(4):482–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.10.002.

Cecil J, McHale C, Hart J, Laidlaw A. Behaviour and burnout in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:25209. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v19.25209.

Demerouti E, Nachreiner F, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

Dyrbye LN, Satele D, West CP. Association of Characteristics of the Learning Environment and US Medical Student Burnout, Empathy, and Career Regret. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;1–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19110.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134.

Elbarazi I, Loney T, Yousef S, Elias A. Prevalence of and factors associated with burnout among health care professionals in Arab countries: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2319-8.

Erschens R, Keifenheim KE, Herrmann-Werner A, Loda T, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Bugaj TJ, Nikendei C, Huhn D, Zipfel S, Junne F. Professional burnout among medical students: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):172–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457213.

Faye-Dumanget C, Carré J, Le Borgne M, Boudoukha PAH. French validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS). J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(6):1247–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12771.

Frajerman A, Morvan Y, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Chaumette B. Burnout in medical students before residency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;55:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.08.006.

Hill AP, Curran T. Multidimensional Perfectionism and Burnout: A Meta-Analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2016;20(3):269–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315596286.

Jagodics B, Szabó É. Student Burnout in Higher Education: A Demand-Resource Model Approach. Trends Psychol. 2022;0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00137-4.

Kaggwa MM, Kajjimu J, Sserunkuma J, Najjuka SM, Atim LM, Olum R, Tagg A, Bongomin F. Prevalence of burnout among university students in low- And middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(8 August):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256402.

Kapasa RL, Hannoun A, Rachidi S, Ilunga MK, Toirambe SE, Tady C, Diamou MT, Khalis M. Evaluation of burn-out among health professionals working at public health surveillance units COVID-19 in Morocco. Archives Des Maladies Professionnelles et de l’Environnement. 2021;82(5):524–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.admp.2021.06.001.

Keith TZ. Multiple Regression and Beyond. An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling. (2nd Editio). Routlegde; 2014. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315749099.

Kilic R, Nasello JA, Melchior V, Triffaux JM. Academic burnout among medical students: respective importance of risk and protective factors. Public Health. 2021;198:187–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.025.

Lahlou L, Benhamza S, Karim N, Obtel M, Razine R. Stress and Burnout Syndrome Among Moroccan Medical Students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Adv Res. 2021;9(12):610–8. https://doi.org/10.21474/ijar01/13949.

Lesener T, Gusy B, Wolter C. The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work Stress. 2019;33(1):76–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065.

Lesener T, Pleiss LS, Gusy B, Wolter C. The study demands-resources framework: An empirical introduction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145183.

Loubir D. Ben, Serhier Z, Diouny S, Battas O, Agoub M, Othmani MB. Prevalence of stress in casablanca medical students: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Med J. 2014;19:1–10. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.19.149.4010.

Madigan DJ, Kim LE, Glandorf HL. Interventions to reduce burnout in students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European J Psychol Educ. 2023;0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00731-3.

Malach Pines A. Occupational burnout: A cross-cultural Israeli Jewish-Arab perspective and its implications for career counselling. Career Dev Int. 2003;8(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430310465516.

Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: a methods review. J Adv Nursing. 2004;48(2):175–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 4th ed. Mindgarden Inc; 2018.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71.

Nteveros A, Kyprianou M, Artemiadis A, Charalampous A, Christoforaki K, Cheilidis S, Germanos O, Bargiotas P, Chatzittofis A, Zis P. Burnout among medical students in Cyprus: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(11 November):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241335.

Prins DJ, van Vendeloo SN, Brand PLP, Van der Velpen I, de Jong K, van den Heijkant F, Van der Heijden FMMA, Prins JT. The relationship between burnout, personality traits, and medical specialty. A national study among Dutch residents. Med Teacher. 2019;41(5):584–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1514459.

Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, Van Der Heijden FMMA, Van De Wiel HBM, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM. Burnout in medical residents: A review. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):788–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02797.x.

Qualtrics. Qualtrics (April 2023). 2023. https://www.qualtrics.com.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023.

Rattrie LTB, Kittler MG, Paul KI. Culture, Burnout, and Engagement: A Meta-Analysis on National Cultural Values as Moderators in JD-R Theory. Appl Psychol. 2020;69(1):176–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12209.

Robins TG, Roberts RM, Sarris A. The role of student burnout in predicting future burnout: exploring the transition from university to the workplace. High Educ Res Dev. 2018;37(1):115–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344827.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023.

Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, Satele D, Horn L, Pippen J, Chu Q, Chew H, Clark WB, Hanley AE, Sloan J, Gradishar WJ. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1127–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4560.

Sosnowska J, De Fruyt F, Hofmans J. Relating neuroticism to emotional exhaustion: a dynamic approach to personality. Front Psychol. 2019;10(October). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02264.

Soto CJ, John OP. Short and extra-short forms of the big five inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J Res Pers. 2017;68:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.02.004.

The World Bank. Morocco. 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/country/morocco.

Thun-Hohenstein L, Höbinger-Ablasser C, Geyerhofer S, Lampert K, Schreuer M, Fritz C. Burnout in medical students. Neuropsychiatrie. 2021;35(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-020-00359-5.

World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. 2016.

Wright T, Mughal F, Babatunde OO, Dikomitis L, Mallen CD, Helliwell T. Burnout among primary health-care professionals in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(6):385-401A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.22.288300.

Yusoff MSB, Hadie SNH, Yasin MAM. The roles of emotional intelligence, neuroticism, and academic stress on the relationship between psychological distress and burnout in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02733-5.

Acknowledgements

In particular, we want to thank the partnering universities in Morocco for their support and expertise in the implementation of our study, and in particular with regard to the recruitment. The ‘Université Mohammed VI des Sciences de la Santé’ (UM6SS) and the ‘Université Moulay Ismaïl’ have contributed significantly.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is an elaboration of the WeMeds study, which received internal funds from KU Leuven (Category 3) under C3/20/040. In addition, a FWO travel grant (V434222N) was obtained to cover costs in Morocco for data collection. Finally, the Project 2 on Environmental Health from the IUC Program (MA2017IUC038A104/VLIR-UOS) also contributed financially to two stays in Morocco.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B., A.M., I.B.K., C.N., M.K., S.E.J. and L.G. all meet the ICMJE criteria. AB, and L.G. conceptualised the design and implementation of the data collection and developed the content of the questionnaire. A.B., A.M., C.N., M.K., S.E.J. and L.G. have contributed significantly to the recruitment of the participants. A.B., I.B.K. and L.G. conducted the statistical analyses, and all authors were part of the interdisciplinary research team that discussed findings. Finally, all authors contributed to the writing of the article and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boone, A., Menouni, A., Korachi, I.B. et al. Burnout and predictive factors among medical students: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ 24, 812 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05792-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05792-6