Abstract

Background

Equitable assessment is critical in competency-based medical education. This study explores differences in key characteristics of qualitative assessments (i.e., narrative comments or assessment feedback) of internal medicine postgraduate resident performance associated with gender and race and ethnicity.

Methods

Analysis of narrative comments included in faculty assessments of resident performance from six internal medicine residency programs was conducted. Content analysis was used to assess two key characteristics of comments- valence (overall positive or negative orientation) and specificity (detailed nature and actionability of comment) – via a blinded, multi-analyst approach. Differences in comment valence and specificity with gender and race and ethnicity were assessed using multilevel regression, controlling for multiple covariates including quantitative competency ratings.

Results

Data included 3,383 evaluations with narrative comments by 597 faculty of 698 residents, including 45% of comments about women residents and 13.2% about residents who identified with race and ethnicities underrepresented in medicine. Most comments were moderately specific and positive. Comments about women residents were more positive (estimate 0.06, p 0.045) but less specific (estimate − 0.07, p 0.002) compared to men. Women residents were more likely to receive non-specific, weakly specific or no comments (adjusted OR 1.29, p 0.012) and less likely to receive highly specific comments (adjusted OR 0.71, p 0.003) or comments with specific examples of things done well or areas for growth (adjusted OR 0.74, p 0.003) than men. Gendered differences in comment specificity and valence were most notable early in training. Comment specificity and valence did not differ with resident race and ethnicity (specificity: estimate 0.03, p 0.32; valence: estimate − 0.05, p 0.26) or faculty gender (specificity: estimate 0.06, p 0.15; valence: estimate 0.02 p 0.54).

Conclusion

There were significant differences in the specificity and valence of qualitative assessments associated with resident gender with women receiving more praising but less specific and actionable comments. This suggests a lost opportunity for well-rounded assessment feedback to the disadvantage of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Inequities associated with gender and race and ethnicity threaten the integrity of assessment [1, 2]. Evidence suggests disparities associated with gender and race and ethnicity occur in quantitative and qualitative learner assessments in medical education [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Most evidence regarding qualitative assessment in medical education has focused on differences associated with gender in the language used and traits ascribed to learners [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Less clear is whether gender may affect other aspects of narrative comments such as emotional tone or level of detail. Limited evidence suggests there may be gender-based differences in the tone and consistency of this assessment feedback [12, 13].

Exploring potential differences in narrative comments is important as these assessments serve a vital role in competency based medical education [16]. Narrative comments provide context to quantitative ratings, inform decisions about resident progress in training, and also play an important formative role as developmental feedback for learners [17]. Moreso than ratings, comments are sourced for programmatic letters of recommendations for awards like chief resident, employment and fellowship opportunities [18, 19]. Disparities in these qualitative assessments could have negative effects on learner growth and opportunity.

This study aims to explore differences based on gender or race/ethnicity in the characteristics of qualitative assessments of Internal Medicine (IM) residents in the United States.

Methods

We applied content analysis to explore characteristics of narrative comments included in faculty assessments of IM resident performance [20, 21].

Data

Data included clinical performance assessments of IM residents during general medicine inpatient rotations from the 2016–2017 academic year at six US IM residency training programs.

In the US, IM resident clinical educational experiences generally occur in blocks of 2–4 weeks, termed clinical rotations, in which residents provide patient care under the supervision of faculty. Faculty assess resident clinical performance in these rotations using the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)’s core competency framework [22]. Typically, clinical performance assessments ask faculty to provide both numerical ratings of resident performance and narrative comments about the residents performance.

These clinical performance assessments communicate information about resident performance to both the trainee and program. Performance assessments play a dual role of informing decisions about learner progress while also providing meaningful feedback to guide learning [17]. This formative role is emphasized as the ACGME requires programs to facilitate resident review of these assessments and use the information to reinforce strengths and modify deficiencies [23].

This study focuses on the written comments provided in clinical performance assessments and does not include verbal feedback to trainees during rotations as that data is not collected routinely. We use terms qualitative assessment (assessments using non-quantitative data), narrative comments (written commentary), and assessment feedback (formative comments included in an assessment) to refer to the textual information provided in response to open-ended questions within these clinical performance assessments [24,25,26].

Each progarm in our study used assessment tools that asked faculty to quantitatively rate resident performance as well as provide narrative comments about the resident’s performance. Three programs in our study asked about resident strengths and areas for improvement while the remaining three programs queried about overall resident performance and also allowed for open text comments organized by the six ACGME core competencies [22]. Comments were grouped into domains based on question stem: strengths and areas for improvement and overall comments and competency-specific comments.

We also collected data on resident characteristics (race and ethnicity, gender, post-graduate year (PGY), baseline IM In-Training Examination (ITE) percentile rank), faculty characteristics (gender, specialty, academic rank, residency educational role), and rotation setting and date. Gender designations were determined by participants’ professional gender identity (gender identity used in their professional role as residents) as known to the residency program director. We acknowledge that one’s professional gender identity may differ from their gender identity expressed in other settings. Race and ethnicity designation was self-reported on residency applications, and we utilized the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)’s definition of URiM as those who are underrepresented in medicine relative to national and local demographics [27]. Faculty gender was determined from institutional profiles; faculty race and ethnicity information was not collected. In our analysis, cis and trans women were included as women and cis and trans men were included as men. Data was extracted from program management systems by program staff and was de-identified before analysis by removing names and gendered pronouns.

Qualitative content analysis

We used content analysis to explore two key characteristics of comments: specificity and valence [20, 21]. We employed a multistage, multi-analyst approach that included familiarization and immersion with data, generating a coding frame through iterative coding and discussion, and applying this coding frame with weekly review of coded data and discussion to achieve consensus [28,29,30]. Research team included men and women as well as physicians and non-physicians. Some team members identified as URiM physicians. The blinded coding team included three physicians (RK, ES, JK) with experience in IM resident assessment and the IM milestone assessment framework [30]. Two investigators independently coded each comment using qualitative coding software (MaxQDA) and reconciled differences via discussion. Cohen’s kappa measure of interrater reliability was > 0.80. We analyzed all comments to strengthen the generalizability of results.

Characteristics of comments

Informed by prior work, we developed two codes (specificity and valence) to capture key characteristics of an assessment comment [12, 31]. Comments from each evaluation were rated in these dimensions. See Table 1.

Specificity refers to the level of detail and degree of actionability of the comment. Specificity was rated on a 4-point scale from non-specific to highly specific based on the number of competencies referenced and the inclusion of specific examples of resident performance and action items for improvement.

Valence refers to the overall positive or negative tone or orientation (praising or critical) of the comment. Valence was rated on a 7-point scale based on the tone and language used to reference performance. Importantly, inclusion of areas for growth did not necessarily detract from the praising or positive orientation of the comment and we differentiated between comments framed as developmental feedback and those phrased as “red flags” for serious concern.

Analysis

We examined the potential relationships of the specificity and valence of narrative comments in an evaluation with resident gender, resident race/ethnicity, resident PGY, and faculty gender using multilevel regression.

We controlled for type of comment (i.e., Overall Performance, Strengths and Areas for Improvement, Competency-specific comments) and quantitative rating of the evaluation, as both may relate to the actionability and tone of narrative comments in an evaluation [31]. We also controlled for the other characteristics of a comment (specificity or valence) as conceptually we suspected that comments that are critical may also be more actionable. To control quantitative ratings, we used a standardized composite competency score for each evaluation by calculating the arithmetic mean of core competency ratings, which was then standardized based on the score distributions at each program.

We then assessed the relationship between specificity and valence of comments and resident gender, PGY, race and ethnicity and faculty gender using mixed-effects regression, accounting for clustering by learner and faculty within programs. We controlled for standardized composite core competency score, type of comment (Overall Performance, Strengths and Areas for Improvement, Competency-specific comments), other characteristic of comment (specificity or valence), program, rotation setting and date, resident characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, PGY, and baseline IM ITE percentile rank), and faculty characteristics (gender, specialty, academic rank, and educational role). In our analysis, men and non-URiM residents were used as the reference group.

To demonstrate the validity of our coded constructs, we analyzed the relationship between the quantitative ratings provided in an evaluation and the characteristics of comments (mean specificity and valence).

We report patterns and differences in specificity and valence of narrative comments associated with gender, race/ethnicity and PGY. Given this study uses a positivist and pragmatic approach, we quantitized our data using the scales described and report differences in scale units [32, 33]. At times, we report odds ratios to convey the difference in more accessible terms. De-identified quotes are presented to ensure confidentiality of participants and sites.

Institutional Review Boards at each institution deemed the study exempted. Funding sources were not involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, or decision to approve publication of the manuscript.

Results

Of 3600 evaluations collected, 3,383 (94%) included narrative comments and were included for analysis (Table 2). Data included this included assessment data for 385 men residents (55.2%) and a 313 women residents (44.8%). Of the faculty, 315 (52.8%) were men and 282 (47.2%) were women. We did not identify any openly gender non-binary participants. Data included 447 assessments of URiM residents (13.2%).

Most assessments included overall performance comments (1959 evaluations) or strengths and areas for improvement (1335 evaluations). Data included more assessments for PGY1 residents than PGY2 and PGY3 residents.

Overall, residents received a mean of 4.8 evaluations with comments and faculty provided a mean of 5.7 evaluations with comments in the academic year studied. There was no significant difference in the likelihood of receiving an evaluation without comments between women and men residents (OR 1.56, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.52).

Comment characteristics: specificity and valence

Table 3 includes representative quotes supporting the specificity and valence scales.

Specificity of comments

Specificity refers to the detailed nature or actionability of the comment. Most overall and strength and weakness comments were moderately specific (52.3%).

Non-specific comments (11.2%) included those that did not reference skills or attributes included in the ACGME’s core competencies. These comments often referenced barriers or qualifiers to the faculty member’s assessment of the resident’s performance (i.e., “Interaction was too brief to say”), offered no suggestions (i.e., “No suggestions”), or were not attributable to a core competency (i.e., “Great job”).

Weakly specific comments (22.1%) referenced one core competency, as the following quote illustrates.

“They are able to recognize when people are sick, make quick decisions, all while maintaining a calm demeanor. They have solid plans for their patients, and I really had to change very little with regards to treatment plan. Overall great job.” Overall Comment, Man PGY2 resident

Moderately specific comments (52.3%), as illustrated by the following quotes, provided either more breadth by referencing 2 or 3 competencies or depth by including specific examples within a competency such as examples of things done well, skills to be improved, or action plans for improvement.

“(First Name) did an extremely good job on (rotation) month. They managed the team extremely well. They accurately knew all the details of their patients’ care and formulated excellent patient care plans that efficiently provided excellent care. They communicated effectively with patients and their families. They will make a terrific (future role). A very, very good job; I was fortunate to have them as my upper-level resident.” Overall Comment, Woman PGY3 resident

Highly specific comments (14.4%) were very detailed and thorough, referencing 4 or more core competencies or included multiple specific examples.

“Dr. (Last Name) exceeded expectations leading a (rotation) team. Their fund of knowledge and clinical judgment are equally impressive. They were able to balance efficiency with education on rounds, finding teaching moments for the interns but also managing time well so that all of the patients were seen, and the team got to noon conference every day. At the bedside with patients and families they set a great example for the interns, quickly establishing rapport and putting people at ease. They worked extremely well with the nurses, case managers, and other floor staff, who universally praised them. The interns on the team admired and respected them. They set a very high bar for themselves and inspired the rest of the team to do the same. They were reflective about their work, looked for ways to improve, and asked proactively for feedback and suggestions. They are a very effective communicator and was able to galvanize the entire team around a common goal. Dr. (Last Name) is a natural and effective leader and I anticipate will continue to be a leader in the program.” Overall Comment, Woman PGY2 resident

Comment specificity and gender, pgy, and race and ethnicity

Controlling for covariates including standardized composite competency rating, comment type, and valence of comment, there was a significant difference in the specificity of comments with resident gender, with women receiving less specific comments than men residents (estimate − 0.07, p 0.002) (Table 4).

Women residents were more likely to receive either no comments or nonspecific/weakly specific comments (adjusted OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.57, p 0.012). Women residents were less likely to receive very highly specific comments (adjusted OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.89, p 0.003) or comments with specific examples of things done well, areas for improvement, or detailed action items for improvement (adjusted OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.90, p 0.003) than men residents.

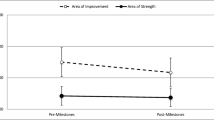

Overall, PGY1 and PGY2 residents received more specific comments as compared to PGY3 residents (Fig. 1A). The difference in specificity of comments received by men and women residents was most notable and significant in PGY1. In PGY1, the difference in the specificity of comments of men and women residents was significant, with women interns receiving less specific comments than men interns (estimate − 0.11, p < 0.001). See Appendix Table.

Specificity and Valence of Narrative Comments by Resident Gender and Post-Graduate Year from study of Association of Gender and Resident Race and Ethnicity and Narrative Comments from Internal Medicine Resident Performance Assessments. Panel 1A: Mean Specificity of Narrative Comments by Resident Post Graduate Year and Gender. Panel 1B: Mean Valence of Narrative Comments by Resident Post Graduate Year and Gender

There was no significant difference in comment specificity based on faculty gender (estimate 0.06, p 0.15) or resident race and ethnicity (estimate 0.03, p 0.32).

Valence of comments

Valence refers to the emotional tone (positive or negative) and orientation (i.e., praise or criticism) of comments. Overall, the valence of comments was positive, with most comments providing praise (36.4%) or strong praise (33.7%).

Praising comments (36.4%) described performance as ‘solid,’ ‘effective,’ or ‘very good’ and often noted that performance was at expected level or comparable to peers. The following quote illustrates a mildly positive, praising comment.

“(First Name) takes great care of their patients. They are very good at data collecting and is doing well this year.” Overall Comment, Man PGY1 resident

Strongly praising or positive comments (33.7%) often included descriptors like ‘excellent’ and cited performance or skills as advanced or above expectations.

“(First Name) did an excellent job! They operate at the level of a PGY-3. They did an excellent job identifying and managing some particularly sick patients and I knew I could completely trust their judgment. I encourage (First Name) to continue to work on discharge planning, particularly determining when a patient is appropriate for discharge.” Strength and Areas for Improvement Comment, Woman PGY2 resident

Very strongly praising comments (25.2%) described performance as ‘outstanding’ or ‘exemplary’ and often noted that the performance stood out from others, was worthy of honor or reward, or ranked highly in the experience of the faculty member.

“(First Name) is one of the strongest residents with whom I have worked in (number) years. They have all the qualities necessary to be a leader in medicine -- knowledge, skill, kindness, and diligence. (First Name) performed at the highest level in all domains. They would be an excellent chief resident.” Overall Comment, Woman PGY1 resident

Comment valence and gender, pgy, and race and ethnicity

Controlling for covariates including standardized composite competency rating, comment type, and specificity of comment, there was a significant difference in comment valence with women residents receiving more positive, praising comments than men residents (estimate 0.06, p 0.045) (Table 4).

Overall, PGY2 residents received more praising comments (Fig. 1B). The difference in valence of comments received by men and women residents was most notable earlier in training. In PGY1, the difference in comment valence for men and women residents was significant, with women interns receiving more positive comments than men (estimate 0.10, p 0.015) (Appendix Table).

There was no difference in valence of comments based on faculty gender (estimate 0.02 p 0.54) or between URiM and non-URiM residents (estimate-0.05, p 0.26).

Ratings and comment valence and specificity

Standardized composite core competency score was associated with comment specificity (estimate − 0.08, p < 0.001) and valence (estimate 0.46, p < 0.001) such that evaluations with lower ratings included more detailed comments and as quantitative ratings increased, the comments included in that evaluation became more positive (Appendix Figure). There was no significant relationship between specificity of a comment and its valence (estimate 0.02, p 0.147). A comment may be highly positive or praising but not necessarily specific, detailed, or actionable.

Discussion

In this multisite study, there were notable differences in the characteristics of narrative comments in performance assessments received by men and women residents. Comments about women residents were more positive but less specific and detailed than those of men residents, even when controlling for numerical ratings. These findings are in contrast with a smaller study in a single U.S. anesthesia program which showed no difference in the likelihood of receiving vague feedback with resident gender [34]. However, our findings are consistent with research looking at performance reviews outside of academia, which found women were less likely to receive specific feedback tied to outcomes, and this occurred with both praise and critical feedback [35,36,37].

We found women received more positively toned comments than men residents while controlling for several variables including the detailed nature of comments and the quantitative ratings accompanying comments. Prior evidence looking at the effects of resident gender on tone of qualitative assessments is limited. A qualitative study of narrative comments in emergency medicine resident assessments noted women residents received more discordant comments, suggesting a mix of praise and criticism across faculty members [13]. Studies of narrative comments in surgical resident assessments have mixed results in terms of gender-based differences in tone of comments [12, 38].

Overall, the differences in specificity and valence of comments received by men and women trainees were most notable earlier in training. For both specificity and valence, the overall differences across training were driven by differences in PGY1. This may be due to the number of evaluations for interns compared to later years. Overall trends in specificity and valence across training years warrant further study.

We found no difference in comment specificity or valence based on gender of faculty assessor. This contrasts with a study of In-Training Evaluation Reports of surgical residents that found women raters provided more positively toned comments than men faculty and comments by women faculty were longer and more detailed than men raters [38].

We found no difference in the characteristics of qualitative comments with resident race and ethnicity. While evidence looking at differences in assessments associated with race and ethnicity is limited, prior work using this same cohort has reported disparities in quantitative ratings with race and ethnicity [5]. The ability to detect differences in specificity and valence of comments related to race and ethnicity may have been limited by low numbers of URiM learners. This may reflect an inability to detect a difference rather than a lack of difference.

Importantly, there are potential implications for these findings for learners and programs in graduate medical education. Performance assessments play a dual role of informing decisions about learner progress while also providing meaningful feedback to guide learning [17]. Feedback is defined as information provided to a learner regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding for the purposes of improvement [39, 40]. Considered within a formative framework, narrative comments serve as feedback to learners about their performance to enable their growth and development [26]. Specific and actionable assessment feedback helps acknowledge learner strengths, name areas for development, and provides clearly defined, actionable items for growth.

Qualitative assessments may also influence program leaders’ perceptions of residents. Assessment feedback is often sourced for programmatic letters of recommendations for awards like chief resident, employment, and fellowship opportunities [18, 19]. As such, disparities in assessment feedback may impact resident growth and opportunity.

Receiving weakly specific comments on performance can be seen as a lost opportunity and hinder the overall growth and development of women residents. This is especially concerning given the greatest difference in specificity of comments found earlier in training when residents are in the most formative stage. Taken together, the findings of positive but less specific comments provided to women residents raises the question of whether the comments contained verbiage which could be construed as ‘empty platitudes’ or praise for skills and attributes outside of the core competencies. Further study is warranted to explore gender-based differences in the content of narrative comments.

Importantly, this study only explored the written comments provided in clinical performance assessments and did not include verbal feedback to trainees during rotations. It is possible that the disparities in the specificity and valence seen in assessment feedback may be mitigated by the verbal feedback provided throughout the rotation. In other words, women may receive positive but less specific narrative comments but more actional verbal feedback throughout the rotation. Study is needed to explore gender differences in verbal feedback including willingness to provide and receptivity to feedback.

While the differences in specificity and valence found were small, evidence suggests that even small differences in performance assessments can have a cascade effect and lead to greater disparities in subsequent outcomes [41]. Differences in assessment imply a difference in the training experience of residents and any evidence of disparities should be sufficient to warrant our concern.

Finally, the findings of this study offer a potential focus for interventions to address inequities in assessment. Providing detailed feedback within and across the core competencies that includes specific examples and plans for improvement can be a target of faculty development. Importantly, as this study demonstrates, the detailed, specific nature of narrative comments can be measured and thus monitored as an indicator of assessment quality and equity [31].

Limitations of this work include retrospective, cross-sectional data which does not allow for assessing differences within residents over time. Assessment tools varied across sites, however we used a rigorous approach to enable comparison. Limitations of our data mean we were not able to explore the comments of those identifying as gender non-binary. This study does not account for all the socioeconomic factors that may influence assessment. The study sample is limited to academic institutions in the United States from 2016 to 17 academic year. It may be useful to study a broader sample of narrative comments to see if these differences persist as context changes.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest there are differences in the characteristics of narrative comments included in performance assessments of men and women trainees, with women receiving more positive but less specific feedback than men. This suggests that disparities in assessments are not confined to ratings or traits ascribed to learners; rather, they manifest in complex ways that can hinder the overall growth and development of women residents. The specificity and tone of narrative comments may be an important target of efforts to promote high-quality, equitable assessment of residents.

Data Availability

Datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions on sharing assessment data. For further inquiry regarding the study, contact the corresponding author. iv.

References

Colbert CY, French JC, Herring ME, Dannefer EF. Fairness: the hidden challenge for competency-based postgraduate medical education programs. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6:347–55.

Klein R, Julian KA, Snyder ED, Koch J, Ufere NN, Volerman A, Vandenberg AE, Schaeffer S, Palamara K. Gender bias in resident assessment in graduate medical education: review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):712–9.

Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Qadri U, Arora VM. Comparison of male vs female Resident milestone evaluations by Faculty during Emergency Medicine Residency Training. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):651–7.

Klein R, Ufere NN, Rao SR, Koch J, Volerman A, Snyder ED, Schaeffer S, Thompson V, Warner AS, Julian KA, Palamara K. Association of gender with learner assessment in graduate medical education. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(7):e2010888.

Klein R, Ufere NN, Schaeffer S, Julian KA, Rao SR, Koch J, Volerman A, Snyder ED, Thompson V, Ganguli I, Burnett-Bowie SA. Association between Resident Race and Ethnicity and Clinical Performance Assessment scores in Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2022;97(9):1351–9.

Klein R, Koch J, Snyder ED, Volerman A, Simon W, Jassal SK, Cosco D, Cioletti A, Ufere NN, Burnett-Bowie SA, Palamara K. Association of Gender and Race/Ethnicity with Internal Medicine In-Training examination performance in Graduate Medical Education. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(9):2194–9.

Axelson RD, Solow CM, Ferguson KJ, Cohen MB. Assessing implicit gender bias in medical student performance evaluations. Eval Health Prof. 2010;33(3):365–85.

Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez-Smith M, Jordan A, Chekroud A, Moore EZ. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in Medical Student performance evaluations. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0181659.

Rojek AE, Khanna R, Yim JW, Gardner R, Lisker S, Hauer KE, Lucey C, Sarkar U. Differences in narrative language in evaluations of medical students by gender and under-represented minority status. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):684–91.

Isaac C, Chertoff J, Lee B, Carnes M. Do students’ and authors’ genders affect evaluations? A linguistic analysis of medical student performance evaluations. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):59–66.

Gold JM, Yemane L, Keppler H, Balasubramanian V, Rassbach CE. Words Matter: examining gender differences in the Language used to evaluate pediatrics residents. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(4):698–704.

Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, McAllister J, Salles A. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217(2):306–13.

Mueller AS, Jenkins TM, Osborne M, Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Arora VM. Gender differences in attending Physicians’ feedback to residents: a qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(5):577–85.

Brewer A, Osborne M, Mueller AS, O’Connor DM, Dayal A, Arora VM. Who gets the benefit of the doubt? Performance evaluations, medical errors, and the production of gender inequality in Emergency Medical Education. Am Sociol Rev. 2020;85(2):247–70.

Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, AMA Manual of Style Committee. Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. Jama. 2021 Aug 17;326(7):621–7.

Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32:676–82.

Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):76–85.

Santhosh L, Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e1920482.

Klein R, Law K, Koch J. Gender representation matters: intervention to solicit medical resident input to enable equity in leadership in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(12 suppl):93–S97. - PubMed.

Neuendorf KA. The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002.

Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Febuary: Sage publications; 2012.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. Available at https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf Accessed July 2017.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. Available at https://www.acgme.org/programs-and-institutions/programs/common-program-requirements/ Accessed July 2023.

Yudkowsky R, Park YS, Downing SM, editors. Assessment in health professions education. Routledge; 2019 Jul. p. 26.

Cook DA, Kuper A, Hatala R, Ginsburg S. When assessment data are words: validity evidence for qualitative educational assessments. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1359–69.

Sargeant JM, Mann KV, Van der Vleuten CP, Metsemakers JF. Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14:399–410.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. Available at https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine. Accessed July 2020.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405.

Tekian A, Park YS, Tilton S, Prunty PF, Abasolo E, Zar F, Cook DA. Competencies and feedback on internal medicine residents’ end-of-rotation assessments over time: qualitative and quantitative analyses. Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1961.

Maxwell JA. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qualitative Inq. 2010;16(6):475–82.

Pratt MG. From the editors: for the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Acad Manag J. 2009;52(5):856–62.

Arkin N, Lai C, Kiwakyou LM, Lochbaum GM, Shafer A, Howard SK, Mariano ER, Fassiotto M. What’s in a word? Qualitative and quantitative analysis of leadership language in anesthesiology resident feedback. J Graduate Med Educ. 2019;11(1):44–52.

Snyder K. Performance review gender bias: High-achieving women are abrasive. Fortune. 2014. http://fortune.com/2014/08/26/performance-review-gender-bias/. Accessed April 10, 2018.

Correll SJ, Simard C. How Vague Feedback is Holding Women Back. Harvard Business Review. 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/research-vague-feedback-is-holding-women-back. Accessed May 2022.

Cecchi-Dimego P. How gender Bias corrupts performance reviews, and what to do about it. Harv Buisness Rev. 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/04/how-gender-bias-corrupts-performance-reviews-and-what-to-do-about-it.

Roshan A, Farooq A, Acai A, Wagner N, Sonnadara RR, Scott TM, Karimuddin AA. The effect of gender dyads on the quality of narrative assessments of general Surgery trainees. Am J Surg. 2022;224(1):179–84.

Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112.

Wisniewski B, Zierer K, Hattie J. The power of feedback revisited: a meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Front Psychol. 2020;10:3087.

Teherani A, Hauer KE, Fernandez A, King TE Jr, Lucey C. How small differences in assessed clinical performance amplify to large differences in grades and awards: a cascade with serious consequences for students underrepresented in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1286–92.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Educational Affairs and the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributed to aspects of study sufficient to warrant inclusion as author, including study design (RK, ES, AV, JK, NU, SA, KJ, VT), data collection(RK, ES, AV, JK, NU, SA, KJ, VT), coding and methods (RK, ES, JK, BW), analysis and interpretation (RK, ES, JK, KJ, BA, KP, SB), and manuscript preparation and review (RK, ES, JK, SA, KJ, KP, BW, BA, YP, AK).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Study methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Boards at each institution in the study (Emory University, University of Alabama Birmingham, University of Virginia, University of Chicago, University of California San Diego, University of California San Francisco, Univeristy of California Los Angelos and Massachusetts General Hospital) and deemed secondary research for which consent was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, R., Snyder, E.D., Koch, J. et al. Analysis of narrative assessments of internal medicine resident performance: are there differences associated with gender or race and ethnicity?. BMC Med Educ 24, 72 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04970-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04970-2