Abstract

Background

Non-technical skill (NTS) teaching is a recent development in medical education that should be applied in medical education, especially in medical specialties that involve critically ill patients, resuscitation, and management, to promote patient safety and improve quality of care. Our study aimed to compare the effects of mini-course training in NTS versus usual practice among emergency residents.

Methods

In this prospective (non-randomized) experimental study, emergency residents in the 2021–2022 academic year at Ramathibodi Hospital, a tertiary care university hospital, were included as participants. They were categorized into groups depending on whether they underwent a two-hour mini-course training on NTS (intervention group) or usual practice (control group). Each participant was assigned a mean NTS score obtained by averaging their scores on communication and teamwork skills given by two independent staff. The outcome was the NTS score before and after intervention at 2 weeks and 16 weeks.

Results

A total of 41 emergency residents were enrolled, with 31 participants in the intervention group and 10 in the control group. The primary outcome, mean total NTS score after 2 weeks and 16 weeks, was shown to be significantly better in intervention groups than control groups (25.85 ± 2.06 vs. 22.30 ± 2.23; P < 0.01, 28.29 ± 2.20 vs. 23.85 ± 2.33; P < 0.01) although the mean total NTS score did not differ between the groups in pre-intervention period. In addition, each week the NTS score of each group increased 0.15 points (95% CI: 0.01–0.28, P = 0.03), although the intervention group showed greater increases than the control (0.24 points) after adjustment for time (95% CI: 0.08–0.39, P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Emergency residents who took an NTS mini-course showed improved mean NTS scores in communication and teamwork skills versus controls 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the training. Attention should be paid to implementing NTS in the curricula for training emergency residents.

Trial registration

This trial was retrospectively registered in the Thai Clinical Trial Registry on 29/11/2022. The TCTR identification number is TCTR20221129006.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-Technical Skills (NTS), also referred to as soft skills, are the set of cognitive and social skills that are not related to a specific job task but are necessary for optimal performance [1, 2]. NTS comprises seven core categories, including Situational Awareness, Decision-Making, Communication, Teamwork, Leadership, Managing Stress, and Coping with Fatigue. Training in NTS was first implemented in the aviation industry as part of Crew Resource Management (CRM)[1] to reduce human error and promote safety. Its success has led to the acceptance of NTS training in many industries that must maintain high standards, including medical care.

NTS training has become an area of particular interest in medical education and many medical specialties [3,4,5] because studies showed its ability to promote patient safety and quality of care in critical situations [6, 7]. Tools such as Anesthetists’ Non-technical Skill (AS-NTS) [8] and Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) [3] were validated for developing professional competencies and introducing effective models for teaching and evaluating NTS.

Even though the tools used to measure NTS have specifications based on medical specialties, they are also applicable in other specialties and situations. For example, NOTSS was initially developed and validated for surgeons in the operating room [9], but a study reported using NOTSS to measure NTS in trauma resuscitation stimulations in a team of emergency medicine and surgical residents [3, 10]. There are seven core categories in which NTS should be applied in healthcare [11].

NTS plays an important role in improving patient care in the emergency department, particularly in communication [12] and teamwork [6]. Teamwork is a skill required for a team to be successful in resuscitating critically ill patients [13]. Communication skills are necessary not only for consultation with other specialties [14] but also for sharing and giving information to patients and relatives, increasing patient satisfaction and decreasing complaints [15].

We aimed to compare the effect of mini-course training for NTS versus usual practice in communication and teamwork scores before, after 2 weeks and after 16 weeks among emergency residents. Two main reasons for choosing only communication and teamwork. First, communication and teamwork are frequently used in routine practice in the emergency department. Second, It’s easily measurable by direct observation.

Methods

Study design

This study was a prospective non-randomized experimental study comparing NTS scores between emergency residents receiving mini-course training on non-technical skills (the intervention group) versus usual practice (the control group) in communication and teamwork scores measured before the course and 2 weeks and 16 weeks after. This study was approved by the Faculty of Medicine, Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects, at Mahidol University’s Ramathibodi Hospital on April 29, 2021 (IRB COA. MURA2021/360).

Study population

This study was conducted at the Emergency Medicine Department of Ramathibodi Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. We assessed the eligibility of all emergency residents in the academic year 2021–2022. We excluded emergency residents who could not undergo the follow-up NTS score evaluation in communication and teamwork at 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the training. All participants provided signed informed consent.

Study intervention

Before starting the mini-course training NTS, we collected baseline characteristics including age, post-graduate year, academic year (resident), marital status, and history of prior communication or teamwork training. All participants underwent an NTS score evaluation 2 months before receiving the intervention. Those who did not participate in the formal training underwent usual practice, which at this institution consists of learning on the job and may receive feedback from staff during daily practice by chance. However, we had the curriculum of formal regular feedback 2 times per year about NTS from academic staff.

In our study, we included two emergency staff members, not involved in the study analysis, who were trained in NTS score assessment by the investigators. We sent an evaluation form to the assessors that included all participants. We did not label for intervention or control group to assessors. They each observed the participant’s service in the emergency room for around 15–30 min and independently assigned the NTS score; then, we used the mean score of the two assessors for the overall NTS score of each participant. We used simulation scenarios to examine the agreement of the two assessors in NTS score assessment for the emergency residents. The level of inter-rater agreement in this reliability test was fair (Cohen’s kappa statistic 0.4, agreement 68.75%).

Emergency residents underwent either mini-course training in NTS communication and teamwork group or usual practice in September 2021 based on their convenience. The mini-course training group had one hour of lectures on communication and teamwork skills, then another hour of simulation and debriefing for practice on communication and teamwork skills. The lecture and simulation on communication and teamwork were delivered by five academic staff members certified in NTS teaching. We added education methods, including self-reflection, feedback, and debriefing from team learning to self-practice in NTS.

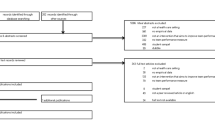

In the first simulation, the objective was interfacility communication for inter-hospital transfers of respiratory failure patients in whom SAR-CoV-2 was detected. The second simulation concerned managing communication and teamwork in emergency department care for traumatic hypotension. The protocol is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Study outcome

The primary outcome was the mean total NTS score 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the NTS mini-course training. Secondary outcomes included the mean communication score, the mean teamwork score, and the scores of each component 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the NTS training. The mean total NTS score was calculated from the sum of the mean communication skill score and teamwork skill score. Communication and teamwork skills were assessed using integration scales adapted from the essential NTS. We designed to evaluate the immediate and delayed effects of the intervention which we adapted follow up time from Gorgas et al. [16].

The scoring system was adapted from Kodate et al. [11] in the communication and teamwork domains, each of which had four categories (Table 1). We used the following rating scale for evaluation: 1 = poor (performance endangered or potentially endangered patient safety, serious remediation is required); 2 = marginal (performance indicated cause for concern, considerable improvement is needed); 3 = acceptable (performance was of a satisfactory standard but could be improved); and 4 = good (performance was of a consistently high standard, enhancing patient safety; it could be used as a positive example for others). These scores were aggregated to provide an overall score that had range of 4–16 in each domain. Higher scores indicated better NTS.

Sample size and statistical analysis

We estimated sample size based on Yule et al. [17] assuming a mean score of NOTSS before and after coaching of 10.8 and 13.8, respectively, with an SD of 4. The maximum score was 16. This study needed sixteen participants to detect potential differences between the two groups, with a two-sample paired-mean test α of 0.05 and a power of 0.8.

For comparison of baseline characteristics between the two groups, continuous variables were reported using mean ± SD for the normal distribution or medians and interquartile ranges in non-parametric tests. Tests for differences employed independent t-tests, or Mann–Whitney U tests as appropriate. For categorical variable data represented with frequency and proportion, tests for difference used Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

The primary outcome and secondary outcome were analyzed using repeated data analysis to detect changes in NTS scores before and 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the training. All statistical analysis was conducted using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 41 emergency resident physicians were enrolled; those who participated in the mini-course training made up the intervention group of 31 participants; the remaining 10 participants (the control group) underwent usual practice.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristic data in each group. Overall, age, marital status, years of post-graduate experience, academic year, and rates of having prior communication and teamwork training were statistically similar between groups. Table 3 demonstrates that the primary outcome of our study, mean total NTS score after 2 weeks and 16 weeks, was significantly better in the mini-course training group than the control group (25.85 ± 2.06 vs. 22.30 ± 2.23; P < 0.01, 28.29 ± 2.20 vs. 23.85 ± 2.33; P < 0.01); the mean total NTS score did not differ between the groups in the pre-intervention period.

The secondary outcome of our study shows that the mean communication skills score prior to the intervention was significantly lower in the mini-course training group than the usual training group (9.76 ± 0.72 vs. 10.50 ± 1.08; P = 0.02); the mini-course training groups had significantly better score after 2 weeks and 16 weeks than the usual training groups (12.76 ± 1.12 vs. 11.05 ± 1.19; P < 0.01, 13.97 ± 1.24 vs. 11.75 ± 1.21; P < 0.01). Evaluation of the communication skills subdomain score revealed that giving information clearly and concisely, including context and intent, receiving information, identifying and tackling barriers to communication, all showed improved scores in the mini-course training group after 2 weeks and 16 weeks compared with the usual training group (Table 4).

The mean teamwork skills score was significantly better in the mini-course training group versus the usual training group both 2 weeks and 16 weeks post-intervention (13.10 ± 1.11 vs. 11.25 ± 1.27; P < 0.01, 14.32 ± 1.09 vs. 12.10 ± 1.26; P < 0.01, respectively). The teamwork skills subdomains (supporting others, solving conflicts, exchanging information, and coordinating activities) showed significant better mean teamwork skill scores after 2 weeks and 16 weeks in the mini-course training group than in the usual training group (Table 4).

Figures 2 and 3, and 4 demonstrate the relationships between the mini-course training group and the usual training group by intervention over time, showing mean changes in total non-technical skills score, mean communication skills score and mean teamwork skills score.

Table 5 demonstrates that the mean total NTS scores at the start of the study were not different by group (coefficient [coef.] 0.94 [95% CI: -0.50–2.38, P = 0.20]). Over time, each group’s NTS score increased 0.15 points every week (95% CI: 0.01–0.28, P = 0.03); however, the mini-course training group showed a greater increase over usual training, 0.24 points after adjustment for time (95% CI: 0.08–0.39, P < 0.01).

At the start of the study, the mean communication score and mean teamwork score were not different between groups (coef. 0.28 [95% CI: -0.49–1.05, P = 0.48] and coef. 0.66 [95% CI: -0.09–1.40, P = 0.08], respectively). Over time, every week, the score of each group increased by 0.07 points (95% CI: 0.00–0.10, P = 0.07) for mean communication score and 0.08 points (95% CI: -0.01–0.15, P = 0.03) for mean teamwork score. The mini-course training group showed a greater increase over time than with usual training, 0.13 points (95% CI: 0.05–0.21, P < 0.01) for mean communication score and 0.11 points (95% CI: 0.03–0.19, P = 0.01) for mean teamwork score.

Discussion

NTS is a new trend in medical education, including in emergency residents training programs. NTS plays a role in improving outcomes and patient safety [1, 2]. We found it to be a modifiable skill: although NTS scores improved over time without intervention, the mini-course training that we conducted showed significant reinforcement for improving NTS.

At the start of the study, both participant groups shared similar baseline characteristics and NTS scores. The study revealed that at 2 weeks and 16 weeks after the mini-course NTS training, the intervention group’s NTS scores were significantly better than those of the usual training group.

The improved NTS scores 2 weeks after the mini-course NTS training may be because the training demonstrated what good communication and teamwork looked like, effectively coaching residents on how to manage situations and improve themselves. This immediate improvement in skill has been reported after communication workshops in emergency medicine [15, 18] as well as in surgical resident training programs in the operating room [17].

Furthermore, we found emergency residents in the mini-course training group had continuously increased NTS scores in both communication and teamwork skills at 16 weeks after intervention. This score increase appears to directly result from both the intervention and time. The continuous improvement of NTS in this study may well be the result of participants applying NTS to practice, as observed in a study on teaching emotional intelligence in emergency medicine residents, which had a positive effect over time on improving emotional intelligence [16].

As a result, we emphasize that attention should be paid to implementing NTS in the training curricula of emergency residents. Continuous and facilitative feedback by the attending staff may further motivate the residents to improve themselves. The potential challenges or barriers to incorporating NTS training into emergency residents training programs are the need for more time in daily practice, a private environment, dedicated resources, and limited training and mentorship. However, NTS are modifiable, and emphasizing them results in better clinical outcomes. NTS have been shown to affect many clinical outcomes in recent studies; for example, better NTS have been reported to have positive relationships with technical performance during stressful CPR [7, 19] and to increase patient satisfaction [15]. Further studies should be conducted to evaluate clinical outcomes after training in NTS.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the inter-rater reliability of the two observers showed only Fair agreement (Cohen’s kappa was 0.4, agreement 68.75%). Consequently, we used the mean average between the two observers to represent the NTS score. We suggest that further studies should develop assessment tools to measure NTS that are adapted to be suitable for specific specialties or institutions. For instance, TEAM may be more appropriate for medical emergency teams [4], and AS-NTS for anesthesiology students [8]. Second, our study was conducted in a single university-affiliated tertiary care hospital, which may limit its generalizability. Third, participants were not randomized but classified into the intervention group according to the convenience of the participants, which may have led to selection bias. The sample size of the control group was 10 which below than calculate. However, we calculated the power of statistic from mean NTS score from both groups, the power was 0.819 (more than 80%). Fourth, the study design allowed an excessive amount of time between allocation and intervention, which may have introduced immortal time bias. Fifth, the investigation team and the evaluating staffs were apart of the academic staff who had formal routine feedback for residents 2 times per year (both intervention group and control group) which may introduce information bias. Also, we had limitations in controlling daily feedback from other academic staff by chance. Finally, our study did not present any effects on the quality of patient care or clinical outcomes due to the intervention or increased NTS.

Conclusions

After adjustment for time interaction, a comparison of NTS score before and 2 weeks and 16 weeks after an NTS mini-course on communication and teamwork skills reveals that this training was associated with improved mean NTS score, mean communication score, and mean teamwork score. We encourage those involved in developing emergency residents curricula and associated healthcare providers to consider implementing NTS training.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are openly available in Harvard Dataverse: “Effect of Mini-course Training Communication and Teamwork on Non-technical skill score in emergency resident: A Prospective experimental study”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QUCOIR.

Abbreviations

- AS-NTS:

-

Anesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- Coef:

-

coefficient

- NOTSS:

-

Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons

- NTS:

-

Non-technical Skills

- TEAM:

-

Team Emergency Assessment Measure

References

Flin RH, O’Connor P, Crichton M. Safety at the sharp end: a guide to non-technical skills. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.; 2008.

Gordon M, Darbyshire D, Baker P. Non-technical skills training to enhance patient safety: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1042–54.

Jung JJ, Borkhoff CM, Juni P, Grantcharov TP. Non-technical skills for surgeons (NOTSS): critical appraisal of its measurement properties. Am J Surg. 2018;216(5):990–7.

Cant RP, Porter JE, Cooper SJ, Roberts K, Wilson I, Gartside C. Improving the non-technical skills of hospital medical emergency teams: the Team Emergency Assessment measure (TEAM). Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):641–6.

Cooper S, Endacott R, Cant R. Measuring non-technical skills in medical emergency care: a review of assessment measures. Open Access Emerg Med. 2010;2:7–16.

Saunders R, Wood E, Coleman A, Gullick K, Graham R, Seaman K. Emergencies within hospital wards: an observational study of the non-technical skills of medical emergency teams. Australas Emerg Care. 2021;24(2):89–95.

Krage R, Zwaan L, Tjon Soei Len L, Kolenbrander MW, van Groeningen D, Loer SA, et al. Relationship between non-technical skills and technical performance during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: does stress have an influence? Emerg Med J. 2017;34(11):728–33.

Moll-Khosrawi P, Kamphausen A, Hampe W, Schulte-Uentrop L, Zimmermann S, Kubitz JC. Anaesthesiology students’ non-technical skills: development and evaluation of a behavioural marker system for students (AS-NTS). BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):205.

Pradarelli JC, Gupta A, Hermosura AH, Murayama KM, Delman KA, Shabahang MM, et al. Non-technical skill assessments across levels of US surgical training. Surgery. 2021;170(3):713–8.

Crossley J, Marriott J, Purdie H, Beard JD. Prospective observational study to evaluate NOTSS (non-technical skills for surgeons) for assessing trainees’ non-technical performance in the operating theatre. Br J Surg. 2011;98(7):1010–20.

Kodate N, Ross A, Anderson JE, Flin R. Non-technical skills (NTS) for enhancing patient safety: achievements and future directions. Japan J Quality Safety Healthcare. 2012;7(4):360–70.

Shields A, Flin R. Paramedics’ non-technical skills: a literature review. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(5):350–4.

Peltonen V, Peltonen L-M, Salanterä S, Hoppu S, Elomaa J, Pappila T, et al. An observational study of technical and non-technical skills in advanced life support in the clinical setting. Resuscitation. 2020;153:162–8.

Nagaraj MB, Lowe JE, Marinica AL, Morshedi BB, Isaacs SM, Miller BL et al. Using trauma video review to assess EMS handoff and trauma team non-technical skills. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021:1–8.

Cinar O, Ak M, Sutcigil L, Congologlu ED, Canbaz H, Kilic E, et al. Communication skills training for emergency medicine residents. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):9–13.

Gorgas DL, Greenberger S, Bahner DP, Way DP. Teaching emotional intelligence: a control group study of a brief educational intervention for emergency medicine residents. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(6):899–906.

Yule S, Parker SH, Wilkinson J, McKinley A, MacDonald J, Neill A, et al. Coaching non-technical skills improves Surgical residents’ performance in a simulated operating room. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1124–30.

Servotte JC, Bragard I, Szyld D, Van Ngoc P, Scholtes B, Van Cauwenberge I, et al. Efficacy of a short role-play training on breaking bad news in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(6):893–902.

Briggs A, Raja AS, Joyce MF, Yule SJ, Jiang W, Lipsitz SR, et al. The role of nontechnical skills in simulated trauma resuscitation. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):732–9.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge contribution of all the staff of Emergency department of Ramathibodi Hospital for their collaborations. We thank John Daniel from Edanz (www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS, TK, NA, TT, CA and WT designed this study and developed the protocol. TK was responsible for data collection. WT and TK were responsible for data analysis. PS, TK and WT wrote the manuscript. PS and WT provided final approval for this version to be published. PS and WT agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (IRB COA. MURA2021/360 Date 29 April 2021). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations such as Declaration of Helsinki, The Belmont Report, CIOMS Guidelines and the International Conference on Harmonization in Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanguanwit, P., Kulrotwichit, T., Tienpratarn, W. et al. Effect of mini-course training in communication and teamwork on non-technical skills score in emergency residents: a prospective experimental study. BMC Med Educ 23, 529 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04507-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04507-7