Abstract

Background

The healthcare system experienced various challenges during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and a wide range of safety measures were implemented, including limiting the number of patients allowed to visit primary care clinics and follow-up through telemedicine clinics. These changes have accelerated the growth of telemedicine in medical education and affected the training of family medicine residents throughout Saudi Arabia. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the experiences of family medicine residents with telemedicine clinics as a part of their clinical training during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 60 family medicine residents at King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. An anonymous 20-item survey was administered between March and April 2022.

Results

The participants included 30 junior and 30 senior residents, with a 100% response rate. The results revealed that most (71.7%) participants preferred in-person visits during residency training, and only 10% preferred telemedicine. In addition, 76.7% of the residents accepted the inclusion of telemedicine clinics in training if such clinics constituted not more than 25% of the training program. Moreover, most participants reported receiving less clinical experience, less supervision, and less discussion time with the attending supervisor when training in telemedicine clinics compared with in-person visits. However, most (68.3%) participants gained communication skills through telemedicine.

Conclusions

Implementing telemedicine in residency training can create various challenges in education and influence clinical training through less experience and less clinical interaction with patients if it is not structured well. With the growth of digital healthcare, further structuring and testing of a paradigm that involves using telemedicine in residents’ training programs prior to implementation should be considered for better training and patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Telemedicine has existed since the early 1960s. Over the years, it has developed and spread considerably, becoming a widely used tool for patient care. The World Health Organization defined telemedicine as “the delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies” [1 p. 9]. Consulting through telephone consultation provides a promising alternative to in-person visits for general practice care [2]. Moreover, telemedicine reduces inefficiencies in the delivery of healthcare, such as reducing patient travel and waiting time [3]. In addition, telemedicine was found to be effective in specialty consultations, primary care assessments, preoperative assessments, and postoperative follow-ups [4, 5].

The World Health Organization declared a global pandemic after cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were confirmed worldwide [6]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals in Saudi Arabia reduced the number of patients allowed to visit primary care clinics by more than 75% of their maximum capacity. This reduction led to the implementation of telemedicine clinics as a part of patient care. Telemedicine is an attractive solution to minimize the risk of virus transmission [7].

The use of telemedicine is growing in clinical practice, and medical residents of the current generation grew up using technology as a major part of their daily lives. Medical residents believe that interactions with telemedicine during their training serve as an important educational tool that supports their understanding of core competencies in practice-based learning, medical knowledge, and patient care [7]. In a 2015 survey of 207 family medicine residencies nationwide, the majority of program directors reported that their facilities had some form of telehealth services; however, actual use was limited and infrequent [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic led the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia to accelerate the growth of digital health by creating and developing mobile health applications and adopting telemedicine in primary care clinics of many tertiary hospitals to improve patient care and minimize the risk of infection. Since many of the tertiary hospitals are teaching hospitals, the adoption of telemedicine introduced a new set of challenges to the family medicine residency program that family medicine residents are involved in as a part of their training. To the best of our knowledge, only one study, conducted in the USA, assessed the perceptions of family medicine residents regarding the use of telemedicine in their training [9]. However, the sample of that study was small. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess experiences with telemedicine among family medicine residents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study group

A cross-sectional study was conducted with family medicine residents at King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The family medicine residency program had 60 residents; all of them were included in the study, with a 100% response rate. Telemedicine clinic visits were introduced to the residents in October 2020. Prior to the clinic appointment, family medicine consultants sorted the booked cases based on the patient’s reason for booking and used their judgment to decide whether the patient required an in-person or telemedicine consultation. The cases included new and follow-up visits. Telemedicine clinics were conducted primarily through telephone rather than video calls. To assess the residents’ experience, a 20-item questionnaire survey was administered between March and April 2022. The questionnaire was anonymous to ensure confidentiality.

Questionnaire design

A validated electronic questionnaire from a similar study conducted in the USA was adapted after obtaining the author’s permission [10]. A few adjustments were made to the questionnaire to match the family medicine program. The adjustments were reviewed and approved by three research experts of family medicine consultants. Questions 1 and 2 related to demographics, including gender and post-graduation year level (residency level). Questions 5, 6, 7, 16, and 17 focused on providing patient-centered care. Question 8 and its subsections assessed residents’ confidence. Common diseases managed in family clinics, including diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, depression and anxiety, chronic headaches, urinary tract infections, back pain, and congestive heart failure, were chosen. Questions 9–11 evaluated system-based practice and work in interdisciplinary teams. Questions 12–15 focused on practice-based learning and improvement and asked family medicine residents about their clinical experience and level of supervision through telemedicine clinics. Questions 18–20 assessed the influence of experiences with telemedicine clinics on family medicine residents’ career plans and inquired their opinions on the acceptable ratio of telemedicine in residency training.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS v. 23.0. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze the difference (1) between post-graduation levels (juniors and seniors) and practice-based learning parameters (amount of attending supervision, clinical experience gain, and acceptable percentage of telemedicine practice) and (2) between post-graduation levels and other variables including communication skill gain, preference of telemedicine practice, and effect of telemedicine on future career decision. P < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference. In addition, Spearman’s correlation was used to test the association between post-graduation level and residents’ confidence.

Results

The questionnaire was distributed to 60 residents (30 juniors and 30 seniors), with a 100% response rate. Of the participants, 48.3% (29) were men and 51.7% (31) were women (Table 1). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, none of the residents had telemedicine experience. The results indicated that if a patient did not answer the call, 81.7% (49) of the participants attempted to call 2–3 times, while only 18.3% (11) attempted to call 4 times or more. Most (47; 78.3%) of the participants could handle 6–8 telemedicine visits per clinic (Table 1).

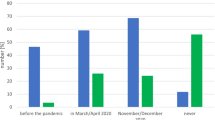

An overall 53.3% (32) of the participants thought that telemedicine may affect their future career decision. However, in-person visit practice was the preferred mode in residency training among most (43; 71.7%) of the participants, and only 10% (6) preferred telemedicine. In addition, 76.7% (46) of the participants accepted the implementation of telemedicine clinics as a part of their training as long as they constituted not more than 25% of the training program (Table 1)(Fig. 1).

Compared with in-person visits, most participants reported receiving less clinical experience, less supervision, and less discussion time with the attending supervisor when training in telemedicine clinics. However, most (41; 68.3%) participants gained communication skills through telemedicine (Table 2). The participants were mostly confident in managing chronic conditions, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism, through telemedicine. In contrast, most participants were not confident in dealing with back pain through telemedicine. The participants stated that telemedicine does not provide the same quality of care as in-person visits because of an increased number of patients lost to follow-up, significant language barriers, and patients feeling uncomfortable with discussing their complaints through telemedicine (Table 2)(Figs. 2 and 3).

Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test were conducted to investigate the association between post-graduation levels (juniors and seniors) and practice-based learning parameters (amount of attending supervision, clinical experience gain, and acceptable percentage of telemedicine practice). There were no statistically significant associations (p = 0.37, p = 0.42, and p = 0.47, respectively; Table 3). In addition, the same tests were used to evaluate the relationship between post-graduation levels and other variables, including communication skill gain, preference of telemedicine practice, and effect of telemedicine on their future career decision. Similarly, there were no significant statistical associations (p = 0.78, p = 1.00, and p = 0.61, respectively; Table 4). Spearman’s correlation was used to test the association between post-graduation level and resident confidence variables. The results revealed a statistically significant correlation between post-graduation level and treating hypothyroidism and urinary tract infections (p = 0.01, and p = 0.01, respectively; Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

Residency training for all specialties was affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to the use of technology as a part of medical education and training. During the COVID-19 pandemic, various fields of the healthcare system, such as telemedicine, medical education, and patient care, were affected [11,12,13].

Our results demonstrated that most of the family medicine residents surveyed in this study preferred in-person visits rather than implementing telemedicine in their training program. In addition, our findings indicated that most participants felt confident in making decisions for managing chronic conditions. Apart from this is because acute conditions such as new onset proctological complaints require in-person visits for further physical examination [20]. Therefore, through our observation, in terms of decision making, we believe that telemedicine should be implemented in residency training regardless of seniority level. Moreover, most residents stated that telemedicine increased the number of patients who did not complete the required labs and imaging studies or were lost to follow-up. In addition, many participants reported experiencing a language barrier caused by telemedicine. These problems can affect the continuity of care and patient trust in their physicians, which are core principles of family medicine practice. Nevertheless, most participants reported gaining communication skills while using telemedicine, which is another core principle of family medicine.

Most of our findings were consistent with that of the Lincoln Medical Center study [9]. Most participants reported gaining less clinical experience through telemedicine clinics and preferred in-person visits, and the majority of the participants reported that the inclusion of telemedicine might affect their future career decision. The participants stated that they prefer only 25% or less of their training to include telemedicine. This could be due to the lower amount of supervision and discussion time with the attending supervisor during the clinic. The reduced supervision and discussion time, in turn, could be due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the high number of attempted calls from the residents to the patients, leading to fewer patients answering and decreased time for discussion with the supervisor. The high number of telemedicine appointments per clinic could be another possible explanation. Previous research conducted in other developed countries identified the absence of a policy framework for telemedicine as a key factor that influenced the implementation and sustainability of telemedicine [14, 15]. One study showed that most residents expressed an overall concern regarding their overall preparedness to conduct telemedicine visits and their ability to provide high-quality care to their patients [16]. The increased use of technology in medical education and training necessitates an organized policy and regulations for implementing telemedicine clinics, including requiring the attendant physician to physically supervise trainees and discuss cases with them. This could improve training for use of telemedicine. A study conducted in France reported that most residents acknowledged the growth and expansion of telemedicine, reported not being well trained to use telemedicine, and were aware that training is mandatory to provide high-quality care [17]. Training in using telemedicine could increase the confidence level of residents during clinical practice [9]. The acceptance of telemedicine practice in Saudi Arabia could result in its significant growth [18]. Appropriate training in telemedicine could alleviate disparities in care access in rural and urban areas [19]. Telemedicine plays an important role in digital health growth. Residents are a part of healthcare providers, and proper training during residency programs can help develop telemedicine.

Conclusion

Residents need to advance their clinical skills and judgment throughout their training, as this will make them better physicians and allow them to approach and effectively manage patients remotely and provide high-quality care. Implementing telemedicine in residency training and medical education requires clear protocols and paradigms designed and tested by experts that help achieve optimal training and enhance patient care.

Our study’s strength lies in being the first study in the Middle East with the largest sample size. However, this study had several limitations. First, it was a single-center study with a small sample involving only the department of family medicine; therefore, it may not represent the residents in other specialties or other hospitals. Second, the study regarded only phone consultations; thus, other modalities of telemedicine should be considered in the future. Third, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and future normalized circumstances should be considered. Finally, the future involvement of telemedicine in residency training requires follow-up studies to assess its effect on such training.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

coronavirus disease 2019

References

World Health Organization. Global observatory for eHealth vol 2 telemedicine: opportunity and developments in member states. World Heal Organ. 2010;2:96.

Downes MJ, Mervin MC, Byrnes JM, Scuffham PA. Telephone consultations for general practice: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0529-0.

Charpentier G, Benhamou PY, Dardari D, Clergeot A, Franc S, Schaepelynck-Belicar P, et al. The Diabeo software enabling individualized insulin dose adjustments combined with telemedicine support improves HbA1c in poorly controlled type 1 diabetic patients: a 6-month, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter trial (TeleDiab 1 study). Diabetes Care. 2011;24:233–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1259.

Lesher AP, Shah SR. Telemedicine in the perioperative experience. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2018;27:102–6. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2018.02.007.

Sood A, Watts SA, Johnson JK, Hirth S, Aron DC. Telemedicine consultation for patients with diabetes mellitus: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:385–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17704346.

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11. March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020, (n.d.). Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

Magadmi MM, Kamel FO, Magadmi RM. Patients’ perceptions and satisfaction regarding teleconsultations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Jeddah. Saudi Arabia. 2020;1–19. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-51755/v1.

Moore MA, Jetty A, Coffman M. Over half of family medicine residency program directors report use of telehealth services. Telemed e-Health. 2019;25:933–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0134.

Ha E, Zwicky K, Yu G, Schechtman A. Developing a telemedicine curriculum for a family medicine residency. PRiMER. 2020;4:1–5. https://doi.org/10.22454/primer.2020.126466.

Chiu CY, Sarwal A, Jawed M, Chemarthi VS, Shabarek N. Telemedicine experience of NYC internal medicine residents during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246762.

Ohannessian R, Duong TA, Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2020;6. https://doi.org/10.2196/18810.

Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, Janga D, Dedeilias P, Sideris M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. 2020;34:1603–11. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.11950.

Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:777–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30226-7.

Correia JC, Lapão LV, Mingas RF, Augusto HA, Balo MB, Maia MR, Geissbuhler A. Implementation of a telemedicine network in Angola: challenges and opportunities. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2018;12:1–14.

Isabalija SR, Mayoka KG, Rwashana A, Mbarika VW. Factors affecting adoption, implementation and sustainability of telemedicine information systems in Uganda. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2011;5:2. https://www.jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/article/view/72.

Lawrence K, Hanley K, Adams J, Sartori DJ, Greene R, Zabar S. Building telemedicine capacity for trainees during the Novel Coronavirus outbreak: a case study and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2675–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05979-9.

Yaghobian S, Ohannessian R, Lampetro T, Riom I, Salles N, de Bustos EM, Moulin T, Mathieu-Fritz A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of telemedicine education and training of french medical students and residents. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;28:248–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20926829.

Alaboudi A, Atkins A, Sharp B, Alzahrani M, Balkhair A, Sunbul T. Perceptions and attitudes of clinical staff towards telemedicine acceptance in Saudi Arabia. Proc IEEE/ACS Int Conf Comput Syst Appl AICCSA. 2016;1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/AICCSA.2016.7945714.

Alshammari F, Hassan S. Perceptions, preferences, and experiences of telemedicine among users of information and communication technology in Saudi Arabia. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2019;13:1. https://www.jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/article/view/240.

Gallo G, Grossi U, Sturiale A, Di Tanna GL, Picciariello A, Pillon S, Mascagni D, Altomare DF, Naldini G, Perinotti R. Telemedicine in Proctology Italian Working Group. E-consensus on telemedicine in proctology: a RAND/UCLA-modified study. Surgery. 2021 Aug;170(2):405–11. Epub 2021 Mar 22. PMID: 33766426.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. We also thank the family medicine residents who participated in this study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Literature review: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Methodology: Ibrahim AlFawaz, Abdullah Alrasheed. Data collection: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Data analysis: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Tables editing: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Writing original draft: Ibrahim AlFawaz. Writing review: Abdullah Alrasheed, Ibrahim AlFawaz. Supervision: Abdullah Alrasheed. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the College of Medicine, King Saud University (Project No. E-21-6185). Informed consent was obtained verbally from all the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

AlFawaz, I., Alrasheed, A.A. Experiences with telemedicine among family medicine residents at king saud university medical city during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 23, 313 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04295-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04295-0