Abstract

Background

In view of the exponential use of the CanMEDS framework along with the lack of rigorous evidence about its applicability in workplace-based medical trainings, further exploring is necessary before accepting the framework as accurate and reliable competency outcomes for postgraduate medical trainings. Therefore, this study investigated whether the CanMEDS key competencies could be used, first, as outcome measures for assessing trainees’ competence in the workplace, and second, as consistent outcome measures across different training settings and phases in a postgraduate General Practitioner’s (GP) Training.

Methods

In a three-round web-based Delphi study, a panel of experts (n = 25–43) was asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale whether the CanMEDS key competencies were feasible for workplace-based assessment, and whether they could be consistently assessed across different training settings and phases. Comments on each CanMEDS key competency were encouraged. Descriptive statistics of the ratings were calculated, while content analysis was used to analyse panellists’ comments.

Results

Out of twenty-seven CanMEDS key competencies, consensus was not reached on six competencies for feasibility of assessment in the workplace, and on eleven for consistency of assessment across training settings and phases. Regarding feasibility, three out of four key competencies under the role “Leader”, one out of two competencies under the role “Health Advocate”, one out of four competencies under the role “Scholar”, and one out of four competencies under the role “Professional” were deemed as not feasible for assessment in a workplace setting. Regarding consistency, consensus was not achieved for one out of five competencies under “Medical Expert”, two out of five competencies under “Communicator”,one out of three competencies under “Collaborator”, one out of two under “Health Advocate”, one out of four competencies under “Scholar”, one out of four competencies under “Professional”. No competency under the role “Leader” was deemed to be consistently assessed across training settings and phases.

Conclusions

The findings indicate a mismatch between the initial intent of the CanMEDS framework and its applicability in the context of workplace-based assessment. Although the CanMEDS framework could offer starting points, further contextualization of the framework is required before implementing in workplace-based postgraduate medical trainings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

In an era of greater accountability, the need for reassurance of medical competence among health professionals and trainees has revived the attention to competency-based medical education (CBME) [1]. This outcome-based approach provides fruitful ground for individual, programmatic, and institutional changes in order to align medical curricula with societal and patient expectations [2]. Implementation of CBME could offer guidance and direction to learners, and, at the same time, transparency and accountability to patients and to the general public. Following the International CBME Collaborators, competence designates an array of physicians’ abilities, whereas competency defines an observable and measurable physicians’ ability [1]. In CBME, predefined competencies and outcomes that go beyond medical knowledge and clinical reasoning are a prerequisite to meet high quality of patient care [3].

Medical educators have repeatedly attempted to define competencies for CBME. The result of these attempts is the creation of different competency frameworks for postgraduate medical education, like the Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) [4]. The CanMEDS competency framework has been originally developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Canada for defining educational outcomes for graduate medical education, and it is currently worldwide the most widely accepted and utilized framework within medical curricula [4, 5]. The CanMEDS framework identifies and describes different outcomes as competencies that physicians should acquire to follow patient-centred care. These competencies are thematically grouped under seven different roles: medical expert, communicator, collaborator, leader, health advocate, scholar, and professional [4]. The framework also splits competencies into two levels, level one contains the key competencies and level two the enabling competencies. The two levels together provide a multifaceted sum of descriptors to comprehend of what is expected by future physicians [6]. By encompassing various aspects of outcomes, the CanMEDS roles provide a comprehensive analytic framework for learning, teaching, and assessing in medical curricula [6].

In a workplace-based curriculum, the CanMEDS competencies could be captured through different workplace-based assessment tools [7]. To facilitate implementation of CBME in postgraduate medical training, changes in curricular structure are necessary. Among other curricular changes, CBME requires aligning learning outcomes with learning and assessment activities, and adopting learning outcomes that support educational continuity [8]. Consequently, as an outcome-based framework, the CanMEDS not only need to align with and accommodate the purposes of workplace-based assessment, but also to document and reflect competency growth across settings and time [3, 8].

Although context dependency and relevance have been demonstrated in the literature before, there is a lack of evidence about the extent to which the CanMEDS key competencies could be applied and implemented as accurate and reliable outcome measures in a workplace-based postgraduate medical training [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate, firstly, whether the CanMEDS key competencies could be assessed in the workplace, and, subsequently, whether they could be consistently assessed across different training settings and phases as to document and reflect competency growth.

Methods

We employed a web-based Delphi study to gather evidence based on consensus ratings on which CanMEDS key competencies had to be evaluated, first, as feasible, and, then as consistent for workplace-based assessments in the Flemish General Practitioner's (GP) Training, in Belgium [13,14,15]. Based on available literature, we discussed and decided on the necessary steps to ensure methodological rigor. Table 1 provides an overview of designing steps, based on the Guidance on Conducting and REportingDElphi Studies (CREDES) guideline [16]. We further elaborate on our methodological decisions considering the CREDES design steps.

Study design

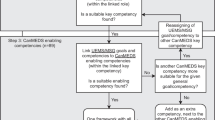

We chose to employ an e-Delphi to recruit panellists from diverse geographic locations within Flanders and to reach a larger group in a cost-efficient way. The online form was also preferred since this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. We defined feasibility as what can be observed in the workplace, and whether the competency formulation is suitable for workplace-based assessment. We defined consistency as what can be consistently observed across different training settings and phases in the workplace (Fig. 1) [13,14,15]. Consensus was defined as 70% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that an item was feasible or consistent for assessment in the workplace [17]. Non-consensus was defined as less than 70% of respondents agreed or strongly agree, and no major change in consensus ratings nor any suggestions for change by the panel after 2 rounds.

To guarantee the reiterative nature of our study, we decided to set a minimum number of three rounds [18, 19]. After each Delphi round, when consensus was achieved for a CanMEDS key competency, the latter was no longer offered for evaluation. Although the traditional Delphi methodology commences with an unstructured round, we chose to follow a semi-structured approach, since our main goal was to validate the predefined CanMEDS framework [4]. Therefore, we used a combination of closed and open-ended questions [20].

In the first round, panellists were asked to evaluate the CanMEDS key competencies as feasible and as consistent based on a 5-point Likert scale. They were also able to provide qualitative comments for each key competency [7, 14]. In the second round, we informed the panellists about the consensus ratings of round 1. In this round, panellists were asked to formulate concrete suggestions for modifications, and rate the two research criteria separetely. A document was also added addressing the issues that arose in round 1 based on qualitative remarks. To provide some clarity about the formulation of the competencies, the CanMEDS, enabling competencies of each key competency were provided to assist the panel with their suggestions. Additionally, we listed and categorized the most frequent qualitative comments to provide an overview. Decisions about modifications on key competencies were clearly communicated. We asked the panel again to evaluate the CanMEDS key competencies as feasible and as consistent for workplace-based assessment based on 5-point Likert scale.

In the third round, we provided summaries of the ratings from the previous rounds. After panellists’ request, we included a list of examples of how each CanMEDS key competency would transfer to the workplace. In this final round, we asked the panellists whether they agree or not that a CanMEDS key competency was feasible and consistent for assessment in the workplace. If not, they were required to specify the reasons for abstaining consensus [15]. Figure 2 shows an overview of the three Delphi rounds.

Study setting

To create a coherent approach across Flanders, four Flemish universities (KU Leuven, University of Ghent, University of Antwerp, and the Flemish Free University of Brussels) have created an interuniversity curriculum for the GP Training which consists of three phases. Practical coordination and decision-making regarding the curriculum are the responsibility of the Interuniversity Centre for GP Training (ICGPT). The ICGPT is responsible among others for allocating clinical internships, organizing exams, arranging fortnightly meetings of GP trainees with tutors, and handling trainees’ learning portfolios where evaluation of competencies is registered.

Selection of panel

To select panellists, we followed a purposive sampling [13, 21]. We set three selection criteria: 1) having sufficient experience as a GP (> 3 years of experience), 2) having experience in mentoring and assessing trainees in the workplace, 3) having sufficient time and willingness to participate [7, 22]. Seventy panellists were invited by the Principal Investigator (BS) via email. To incorporate a wide range of opinions, the panel consisted of both GP trainers and GP tutors [23]. GP trainers were workplace-based trainers assisting trainees during their internship, while GP tutors were associated with a university providing guidance and facilitating peer learning and support (10–15 trainees per group) twice monthly. Both groups were responsible for assessing trainees in the workplace. Panellists resided in different provinces of Flanders to minimize converging ideas and to ensure reliability [13, 23]. Although there is no consensus about an appropriate sample size for a Delphi design, a number of 15–30 panellists could yield reliable results [23, 24]. In our study, we selected panellists that had received the same medical background and hold general understanding in the field of interest. In addition, to determine sample size, we took into consideration feasibility parameters to obtain a good response rate, such as providing large time spans for each Delphi round and reasonable required time to completion.

Development and pilot of Delphi survey

The 27 CanMEDS key competencies were translated from English to Dutch, because the panel was Dutch speaking. Figure 3 graphically illustrates how the Delphi survey was constructed. First, the CanMEDS competencies were translated by five researchers separately. After discussing and evaluating all translations, we decided to keep the Dutch translation as close as possible to the original English framework. Secondly, to validate the translation and pilot the instrument, we sent it to a group of medical professionals to comment on it. Thirdly, once feedback was received and the Dutch translation was finalized, the Dutch version of the framework was back translated to English to confirm the accuracy of the translation [25].

Every Delphi round consisted of an introductory part, the CanMEDS key competencies evaluation, and an ending section. In the introduction, the purpose of each round was explained, and decision rules were communicated. We added the ending section to provide space to the panel for communication and feedback not related to the CanMEDS key competencies (e.g., necessary time to completion, remarks about layout). To avoid confusion among the different CanMEDS roles, the key competencies were grouped per role. Figure 4 illustrates how the survey items were displayed prior to any consensus had been reached.

Data collection and analysis

To collect our data, we used the Qualtrics XM Platform. This online tool allowed for maintaining anonymity among the panellists [26]. A personal link was sent via email to each panellist. This allowed following-up response rates and sending reminders to specific members. Due to high workload caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, each round lasted four weeks. We opted for a flexible approach towards the panellists to increase the response rate of each round. Reminders were weekly sent to members that had not completed the survey [26]. Data collection took place between October 2020 and February 2021. For analysing quantitative data, we calculated descriptive statistics of every item using SPSS 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics 27). We used Microsoft Excel to list and categorize qualitative data. Panellists’ comments were anonymously and literally registered. For analysing qualitative data, we used content analysis [27].

Role of research team to prevent bias

Methodological decisions made by the research team were in line with the available literature. We predefined and stipulated methodological steps before commencing the study. We applied, monitored, and evaluated these steps during the study. The results of each round were discussed by the research team, while qualitative data were interpreted by two researchers for researcher triangulation [28].

Results

Initially, 53 GP trainers and GP tutors chose to participate in the panel. Forty-three out of 53 responded in the first Delphi round (response rate of 89.4%) (Table 2). Twenty-five out of 43 were female, while 18 were male (Table 3). Most panellists (n = 27) were 36 years old or older and mainly GP trainers (n = 31) with at least 5 years of experience (n = 27) in guiding GP trainees in the workplace, and at least 5 years of experience (n = 26) in assessing GP trainees in the workplace. The second Delphi round had a response rate of 88.9% (n = 33), while the third round had a response rate of 76.12% (n = 24) (Table 2). Panellists who chose to withdraw their participation attributed this to the COVID-19 related increase of workload in their clinical practice. Tables 4 and 5 provide an overview of the level of consensus per Delphi round for feasibility and consistency of assessment respectively. An additional file presents the number of comments on feasibility and consistency of assessment per CanMEDS key competency, per role, and per Delphi round (see Additional file 1).

Delphi round 1

In the first Delphi round, five out of 27 CanMEDS competencies reached a positive 70% consensus rate for feasibility and 3 competencies for consistency (Tables 4 and 5 respectively). In total, the panellists gave 154 qualitative comments, 130 comment about feasibility and 24 about consistency of assessment. Those comments were clustered into six main categories: 1. CanMEDS key competency not suitable for workplace-based assessment via a portfolio (n = 46), 2. Vague formulation of CanMEDS key competency (n = 19), 3. Assessment of CanMEDS key competency dependent on phase in GP Training (n = 16), 4. CanMEDS key competency not applicable during GP Training (n = 15), 5. Assessment of some CanMEDS key competencies dependent on location of clinical practice and patient population (n = 12), and 6. Assessment of CanMEDS key competency dependent on trainer and/or trainee (n = 12).

Delphi round 2

In the second Delphi round, the panel was asked to rate 22 CanMEDS key competencies for feasibility and 23 for consistency of assessment in the workplace. As seen in Table 4 and in Table 5, the panel reached consensus for 8 out of 22 CanMEDS key competencies for feasibility and for 8 out of 23 for consistency of assessment. Overall, the consensus rates increased. However, a key competency (n°4) under the role “Leader” had lower scores on both feasibility and consistency comparing to the ones from round one (Tables 4 and 5). Additionally, key competency n°1 under “Leader” scored lower on consistency than in round 1, while consistency consensus rates on key competency n°2 under “Communicator” also decreased in round 2. No adjustments were made to the formulation since no panellists’ comments suggested any alterations.

In total, 117 remarks were given by the panel that were listed in four main clusters: 1. Vague formulation (n = 48), 2. CanMEDS key competency not applicable in GP Training (n = 13), 3. Suggestions for operationalization (n = 14), and 4. CanMEDS key competency could only be assessed by GP trainer (n = 10). Two comments were about the fact that assessment of some key competencies was dependent on the location of clinical practice or the context, one comment was about dependency of assessment on training phase, while two comments suggested some overlap between key competencies n°3 and n°4 under the “Medical Expert” role. Fifteen comments were deemed as not relevant and, therefore, categorized as others.

At this point, despite the lack of concrete suggestions, low consensus levels on the key competencies under the “Leader” role led to modifying three out of four key competencies. More modifications were made to key competency n°2 under “Health Advocate” to make it more comprehensible, while key competency n°2 under “Scholar” was also modified to emphasize the importance of educating colleagues in the same discipline. Additional file 2 illustrates in detail the CanMEDS competencies that were modified (see Additional file 2). To ensure that the modifications aligned with the CanMEDS framework, we ensured that the modified competencies contained the same key words and kept the same focus as the original CanMEDS competencies. These modifications were based on all the data after two Delphi rounds and after discussions within the research team.

Delphi round 3

The third Delphi round included 12 CanMEDS key competencies to be rated for feasibility of assessment, and 15 to be rated for consistency of assessment in the workplace. In this round, 6 out of 12 competencies were rated as feasible, while 4 out 15 were rated as consistent. Panellists made 39 comments about the importance of the CanMEDS competencies for the workplace and suggestions about the way of assessing them in the clinical setting. Panellists did not agree on 6 CanMEDS key competencies about feasibility and on 11 key competencies about consistency. No further round deemed necessary since panellists’ comments did not provide any insights for further modifications.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to collect evidence about applying and implementing the CanMEDS competency famework for workplace-based assessment by employing a Delphi study. The CanMEDS competency framework is well-known globally and has increasingly been incorporated in postgraduate medical education [6]. A competency framework can facilitate the development of competencies, albeit it is not the primary goal. Although an outcome-based approach would not lead to learning itself, it undoubtfully establishes all the conditions leading to learning. Implementing competency frameworks prerequisites defining a clear path of the desired learning outcomes for the learners, providing occasions to exercise these outcomes within and across settings, creating opportunities for assessment and feedback, and enhancing reflection on individual performance [29]. Subsequently, a developmental learning trajectory and competency growth are presumably inherent components of competency frameworks.

However, applicability of the CanMEDS framework seems to be dependent on the context and on medical specialty, while evidence about how competency growth can be documented and reflected through the framework is scarce [9, 30, 31]. This study focused on two criteria, feasibility of assessment and consistency of assessment across training settings and phases, embedded in a workplace-based postgraduate GP Training. Our findings show issues related to the fitness-for- purpose of the CanMEDS key competencies, and to the extent that they can be used for assessment purposes throughout the course of a workplace-based postgraduate training.

Regarding the assessment feasibility, our research indicates that not all CanMEDS key competencies could be clearly related to observable behaviour. Some CanMEDS key competencies under the “Leader”, “Health Advocate”, and “Professional” role got notably lower scores (< 50%) compared to competencies under other CanMEDS roles, such as “Medical Expert”, “Communicator”, and “Scholar”. The big discrepancies in the rating scores might imply that the panel experienced difficulties in associating how those CanMEDS competencies could be transferred and translated into assessment activities in the workplace. This is in line with previous research showing difficulties in applying and using the roles of “Health Advocate and “Leader” in undergraduate medical curricula [7]. Difficulty in applying the CanMEDS key competencies in workplace-based assessment has been attributed to the lack of coherent and concrete descriptions, in undergraduate medical education [7]. In postgraduate medical education, difficulty in implementing the CanMEDS non-medical competencies has been associated with the lack of training for workplace trainers [32]. In our study, panellists also seemed to be more familiar with competencies focusing on medical knowledge, clinical and communication skills rather than with competencies involving societal and public engagement. Clearly, the predominance of clinical and communication skills reflects the role of a GP in primary health [33]. However, medical educators should consider that public education and engagement is a prerequisite for a more equitable and patient-centred healthcare system [34].

Our exploration of consistency across training settings and phases of the CanMEDS key competencies yielded unanticipated results as well. Similar patterns as in the ratings of assessment feasibility were also found in those regarding assessment consistency of the CanMEDS key competencies. Strikingly, almost half of the CanMEDS key competencies seemed unsuitable for consistently being observed in the workplace across different training settings and phases. Remarkably, none of the key competencies under the “Leader” role was deemed as consistent. Presumably, the panel may have reported consistency based on their role in the GP Training. They seemed to pay attention to under which conditions (e.g., comments about “Practice/context dependent”) and by whom (e.g., comments about assesed “only by trainer”) each competency could be assessed. Our results suggest a potential mismatch between the CanMEDS key competencies and certain training settings and phases. Evidence in existing literature also shows that medical students associate the least the roles of “Leader”, “Health Advocate”, “Collaborator”, and “Professional” to their learning activities [35]. This problematic might indicate a dissociation between the CanMEDS framework and its ability to document and reflect competency growth across different training settings and phases.

Our findings suggest that there is a gap between the initial intent of the CanMEDS competency framework and its applicability when it comes to workplace-based assessment [12]. Although the importance of the framework was reinstated by the panel, the difficulty of reaching consensus throughout the three Delphi rounds elucidates issues regarding its implementation in the clinical workplace. The CanMEDS key competencies might offer a starting point for structuring workplace-based assessment and capturing medical competence. Nevertheless, further refinement and contextualisation of the framework is necessary to assist observations of trainees’ behaviour involving all seven CanMEDS roles during clinical practice. Future research should explore implementation issues in different health care contexts and settings to gather more evidence on the CanMEDS framework.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this Delphi study. Notably the fact that the CanMEDS framework was translated in Dutch might have caused some degree of linguistic bias. Since language arguably carries cultural associations and meanings, a translation of the original framework could presumably miss cultural elements inherent to the Flemish GP Training. However, choosing to stay as close to the original framework as possible implies that our findings could be generalized and used in other international contexts. Furthermore, although we provided explicit instructions on how to fill in each round, we cannot exclude that some panellists might have been confused about how to respond to the set of our research questions. Another limitation that needs to be acknowledged is the high dropout rate, since 43 panellists had initially participated in round 1. Unfortunately, the beginning of our study coincided with the onset of a COVID-19 wave. Consequently, the increased workload in clinical practice did not allow some panellists to further participate in this study. A final limitation is that the Delphi method is merely a consensus method based on experts’ opinion. The panel might have answered our research questions having their own preconceptions and interpretations of the CanMEDS framework, for example, how they understand its applicability and implementation in the clinical workplace. Admittedly, this limitation is inherent in every opinion-based method. Nevertheless, by comprehensively describing and justifying every methodological choice, it can be sufficiently argued that our findings are credible and useful.

Conclusions

This study aimed to gather evidence on the applicability and implementation of the CanMEDS key competencies for workplace-based assessment purposes. Given that CBME is increasingly implemented across the globe, the findings provide some insight into the implementation of the CanMEDS framework and its fitness-for-purpose for assessment in the workplace. Drawing on the results of this Delphi study, adapting and adopting the current CanMEDS key competencies should be considered before implementation in postgraduate medical trainings. The challenge for medical educators relates to how to encompass and capture in a workplace-based learning environment aspects of medical competence besides medical knowledge, and clinical and communication skills. Lastly, for CBME to pertain, more attention should be paid to how the CanMEDS competencies could be used as educational outcomes across different training settings and phases. There is a need for rigorous evidence on how the CanMEDS framework can document and reflect competency growth in the workplace.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- CBME:

-

Competency-based medical education

- CanMEDS:

-

Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists

- CREDES:

-

Guidance on Conducting and REportingDElphi Studies guideline

- ICGPT:

-

Interuniversity Centre for GP Training

References

Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–45.

Caverzagie KJ, Nousiainen MT, Ferguson PC, Ten Cate O, Ross S, Harris KA, et al. Overarching challenges to the implementation of competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):588–93.

Ferguson PC, Caverzagie KJ, Nousiainen MT, Snell L. Changing the culture of medical training: an important step toward the implementation of competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):599–602.

Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework: Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada. 2015.

Norman G. CanMEDS and other outcomes. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2011;16(5):547–51.

Pangaro L, ten Cate O. Frameworks for learner assessment in medicine: AMEE Guide No. 78. Med Teach. 2013;35(6):e1197–210.

Michels NR, Denekens J, Driessen EW, Van Gaal LF, Bossaert LL, De Winter BY. A Delphi study to construct a CanMEDS competence based inventory applicable for workplace assessment. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:86.

Nousiainen MT, Caverzagie KJ, Ferguson PC, Frank JR. Implementing competency-based medical education: What changes in curricular structure and processes are needed? Med Teach. 2017;39(6):594–8.

Stutsky BJ, Singer M, Renaud R. Determining the weighting and relative importance of CanMEDS roles and competencies. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):1–7.

van der Lee N, Fokkema JP, Westerman M, Driessen EW, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ, et al. The CanMEDS framework: relevant but not quite the whole story. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):949–55.

Anderson HL, Kurtz J, West DC. Implementation and use of workplace-based assessment in clinical learning environments: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S164–74.

Campbell C, Hendry P, Delva D, Danilovich N, Kitto S. Implementing competency-based medical education in family medicine: a scoping review on residency programs and family practices in Canada and the United States. Fam Med. 2020;52(4):246–54.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15.

Embo M, Helsloot K, Michels N, Valcke M. A Delphi study to validate competency-based criteria to assess undergraduate midwifery students’ competencies in the maternity ward. Midwifery. 2017;53:1–8.

Chia-Chien H, Brian AS. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8.

Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706.

Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):14–9.

de Loë RC, Melnychuk N, Murray D, Plummer R. Advancing the state of policy Delphi practice: a systematic review evaluating methodological evolution, innovation, and opportunities. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2016;104:78–88.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–9.

Foth T, Efstathiou N, Vanderspank-Wright B, Ufholz L-A, Dütthorn N, Zimansky M, et al. The use of Delphi and nominal group technique in nursing education: a review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:112–20.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2002.

Skulmoski GJ, Hartman FT, Krahn J. The Delphi method for graduate research. J Inf Technol Educ. 2007;6(1):1–21.

de Villiers MR, de Villiers PJ, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach. 2005;27(7):639–43.

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):1–12.

Ozolins U, Hale S, Cheng X, Hyatt A, Schofield P. Translation and back-translation methodology in health research - a critique. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(1):69–77.

Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):14–9.

Savin-Baden MMCH. Qualitative research : the essential guide to theory and practice. London; New York: Routledge; 2013.

Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–7.

Swing SR. Perspectives on competency-based medical education from the learning sciences. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):663–8.

Ringsted C, Hansen TL, Davis D, Scherpbier A. Are some of the challenging aspects of the CanMEDS roles valid outside Canada? Med Educ. 2006;40(8):807–15.

Bonnie LHA, Nasori M, Visser MRM, Kramer AWM, van Dijk N. Feasibility, and validity aspects of Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA)-based assessment in general practice training. Educ Prim Care. 2022;33(2):69–76.

Jippes E, Van Luijk SJ, Pols J, Achterkamp MC, Brand PL, Van Engelen JM. Facilitators and barriers to a nationwide implementation of competency-based postgraduate medical curricula: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2012;34(8):e589-602.

Tavakoly Sany SB, Behzhad F, Ferns G, Peyman N. Communication skills training for physicians improves health literacy and medical outcomes among patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10.

Organization WH. Towards people-centred health systems: An innovative approach for better health outcomes. In: Europe ROf, editor. Denmark: World Health Organization; 2013.

Kalén S, Lachmann H, Varttinen M, Möller R, Bexelius TS, Ponzer S. Medical students’ experiences of their own professional development during three clinical terms: a prospective follow-up study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):1–10.

Acknowledgements

The CanMEDS competency framework was reproduced after receiving approval by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (Copyright © 2015 The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e. Reproduced with permission.). The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Mrs. Oona Janssens, Mrs. Marieke Robbrecht, and Ms. Sofie Van Ostaeyen that assisted in the design of the study. We would also like to thank and acknowledge Prof. dr. Martin Valcke for facilitating this study through the SBO SCAFFOLD project (www.sbo-scaffold.com). Additionally, we would like to thank Mrs. An Stockmans and Mr. Guy Gielis from the Interuniversity Centre for GP Training for assisting with recruiting panellists. Lastly, we would like to thank our participants who accepted to participate in this study during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

This study is a part of the SBO SCAFFOLD project (www.sbo-scaffold.com) funded by Research Foundation Flanders (FWO). The funding organisation was not involved in any stage of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (VA, SP, JE, ME, NM, BS) contributed to designing the study. VA collected the data, led the data analysis, and wrote this manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants had to actively consent by signing an informed consent form before participating in the study. Additionally, this study has been approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC) KU Leuven (G-2020–1726-R2(MIN)).

Consent for publication

Participants actively consented for data publication when signing the informed consent form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table 6. Number of panellists’ comments per CanMEDS competency and research criterion in every Delphi round.

Additional file 2:

Table 7. Overview of modified CanMEDS key competencies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Andreou, V., Peters, S., Eggermont, J. et al. Fitness-for-purpose of the CanMEDS competencies for workplace-based assessment in General Practitioner’s Training: a Delphi study. BMC Med Educ 23, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04207-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04207-2