Abstract

Background

In Turkey, most final-year medical students prepare for the Examination for Specialty in Medicine in a high-stress environment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on final-year medical student general psychological distress during preparation for the Examination for Specialty in Turkey. We aim to evaluate psychological distress and understand the variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress levels among final-year medical students preparing for the Examination for Specialty.

Methods

A self-reporting, anonymous, cross-sectional survey with 21 items consisting of demographic variables, custom variables directed for this study, and the DASS-21 was utilized. Survey results were expounded based on univariate analysis and multivariate linear regression analysis.

Results

Our study revealed four variables associated with impaired mental wellness among final-year medical students during preparation for the examination for Specialty: attendance to preparatory courses, duration of preparation, consideration of quitting studying, and psychiatric drug usage/ongoing psychotherapy.

Discussion

Considering that physician mental wellness is one of the most crucial determinants of healthcare quality, impaired mental wellness among future physicians is an obstacle to a well-functioning healthcare system. Our study targets researchers and authorities, who should focus on medical student mental wellness, and medical students themselves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines wellness as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Poor mental wellness among physicians has consequences for both physicians as an individual and the whole healthcare system [1,2,3]. For instance, unwell physicians are more likely to forfeit their licenses due to medical errors and malpractice cases [4]. Research indicates a strong association between physician mental wellness and the compassionate care they provide for patients [1, 5, 6]. Predictably, a physician's productivity under stress is much lower than a healthy colleague's [7, 8]. Therefore, the importance of physician mental wellness could be considered equivalent to the importance of high-quality healthcare.

Studies on medical student mental health are imperative since medical students are future physicians, and unwell medical students may grow up as unwell physicians. Besides, medical students already have an essential role in the healthcare system as a part of their clinical education. Psychological distress among medical students is associated with profound consequences: worse academic performance, higher rates of burnout, loss of empathy, reduced quality of life, poor mental health, and suicidal ideation [9, 10]. We believe that one could forecast the future of the healthcare system by assessing medical student mental wellness and could implement novel policies to prevent further impairment.

Medical student mental wellness has attracted more attention due to studies emphasizing that most medical students endure severe psychological distress during medical school, a critical period for professional growth and personal development [11,12,13,14,15]. Although students' mental health profiles are average before medical school [16], they end up with significantly higher rates of burnout, depression, and other mental illnesses than their non-medical peers, indicating intense emotional consumption during medical training [1, 17,18,19,20]. According to a recent study, a significant amount of medical students and residents experience above-normal psychological distress (41.5%) or high to very high psychological distress (9.2%) [21]. that may progress into depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation [11, 22, 23].

The most stressful aspects of medical training include preparing for exams and acquiring medical skills, which can lead to high levels of anxiety among medical students [24, 25]. Confirming the previous data, most medical students at a United States (US) medical school attributed poor wellness to the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) preparation process [26]. Thus, medical students who prepare for exams for postgraduate medical education are at stake regarding the consequences of poor mental wellness: depression, anxiety, burnout, low attention, medical errors, and negligence [14, 27, 28]. Therefore, a study on the contributors to poor mental wellness among medical students who prepare for such exams is required to comprehend previous findings; our study satisfies the need with its unique sample.

Previous studies revealed significant findings comparing first- and final-year medical students. One study found that final-year medical students had lower quality of life than first-year students, indicating a gradual decline in mental health during medical school [29]. In final-year medical students, almost all stressors are about the medical profession: medical responsibility, exams for postgraduate medical education, and less leisure time [30]. In Turkey, the preparation period for specialty examination requires intense engagement with question banks and trial tests organized by commercial preparatory courses. Besides other factors, the frequency of test-taking may also explain the higher anxiety in the final year, given that the high frequency of test-taking disrupts mental wellness [31]. In Turkey, Tıpta Uzmanlık Sınavı (Examination for Specialty in Medicine [will be mentioned as ESM from this point forward]) presumably exacerbates anxiety and stress, considering the competitive environment due to the growing number of medical schools leading to more competition among the candidates.

In Turkey, every medical student graduates as a primary care physician after six years of education. As reported by earlier studies, most of them (90%) aspire to become specialists [32]. To pursue a specialty in medicine, graduate students must pass the ESM, which assesses examinees' knowledge and understanding of basic and clinical sciences through 240 single-best-answer, multiple-choice questions. Examinees' performance rank and preferences determine the medical institutions they are assigned to for specialty training. Despite increased quotas for specialists, the ESM remains competitive due to the growing number of medical students, the accumulation of preferences in a few major branches, and the reapplication of dissatisfied specialists or failed graduates. Therefore, final-year medical students prioritize their preparation for the ESM at the cost of their mental wellness.

Although concerns about medical student mental wellness draw attention, the attempts to prevent impairment in the first place are not enough [1, 17]. The current standard for medical school education needs renovation. Unfortunately, current medical education models are limited regarding psychological training and medical skills. Regarding these, physicians are incapable of managing their mental wellness [1, 33]. In order to raise resilient physicians despite the high-stress environment, medical schools should foster student mental wellness through an adequate curriculum incorporating self-care education and coping strategies with medical training. If the factors responsible for the decline in medical student mental wellness are well-understood, authorities may develop a better educational environment with a comprehensive curriculum and psychological assistance. Therefore, we aim to understand how ESM affects mental wellness in final-year Turkish medical students by assessing their depression, anxiety, and stress levels which is a crucial aspect of mental wellness; and to pave the way for new implications targeting improved mental wellness among medical students. This study is the first to assess final-year medical students' general psychological distress by evaluating their depression, anxiety, and stress level during the preparation of ESM in Turkey.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

This cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted at Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine, in March–April 2021. Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine is a public medical school in Istanbul which is one of the oldest and most prestigious medical schools in Turkey. The English program typically accepts between 80 and 100 students per year, while the Turkish program accepts between 250 and 300 students annually while it is subject to change. Medical students in the final year of their medical education were targeted. The first three years of the medical school program at the Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine are preclinical, while the fourth and fifth years are when the clinical clerkships are done. The sixth year, the final year, is a year of pre-graduate internship. In their final year, medical students serve as full-time intern doctors in the Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine Hospitals. In addition to rotations in major branches, such as the departments of internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, emergency medicine, gynecology, and obstetrics, they rotate in minor branches. They do not take exams at the institution, but their full-time internship with regular night shifts makes it difficult for them to study for ESM. Thus, the participants of this study were sixth-year medical students. An online survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). It was distributed to all eligible students through WhatsApp and Telegram text messages, owing to a lack of a proper students' email database. Two reminder text messages were also sent out ten days apart. A link to the survey and detailed instructions were included in the text messages. Before starting the survey, participants were provided a summary of the study, explaining its purpose, its scientific and academic nature, terms of anonymity, and confidentiality. Participants consented to their anonymized data being used by checking a box. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine.

Questionnaire

A self-reporting, anonymous, cross-sectional survey was conducted using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and also 21 custom questions regarding demographic, educational, and custom variables designed for this study [34]. Nine demographic and educational variables consisted of age, sex, the language of education, grade point average (GPA), relationship status, socioeconomic status, duration of preparation, weekly study hours, and attendance to ESM preparatory courses.

Additional twelve questions that can be related to mental wellness were asked. Three of them were related to the perceived status of their study: (1) whether they consider their study sufficient, (2) think that they get the worth of their study, and (3) consider quitting studying or not. Furthermore, one question regarding their reflection on working abroad was present. Psychiatric drugs and prescription stimulants usage were evaluated, as well as cigarette, alcohol, or drug consumption. The remaining questions were about setting aside time for themselves and family or friends, mindfulness to nutrition, sleep sufficiency, and exercising.

The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-assessment tool for healthcare providers. It had good internal consistency (all a > 0.80), test–retest reliability (all Mutual Information Scores > 0.80), and content and discriminant validity in the Turkish adaptation study of the scale [35]. All DASS-21 items are on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Eight of the 18 items are reverse-scored. Each subscale is made up of the averages of select items (eight "Depression", nine "Anxiety", and fourteen "Stress" items). The overall mean score ("Overall DASS-21") is made up of the averages of all 21 items. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, which implies reduced mental wellness.

Statistical analysis

We calculated frequencies for categorical variables, means with standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Spearman's rank correlation was conducted to assess the relationship between the only continuous variable age and dependent variables, DASS-21, and its subscales' mean scores. For categorical variables with two groups, we performed an independent t-test for normally distributed dependent variables with equal variances, Welch's t-test for normally distributed dependent variables with unequal variances, and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed dependent variables. For categorical variables with three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed dependent variables and the Kruskal Wallis test for non-normally distributed dependent variables were performed. Variables with a p-value smaller than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were used in the multivariate linear regression models. A p-value of 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.1.3 [36].

Results

Demographic findings

A total of 146 final-year medical students participated in this study; 101 responses were complete submissions and used in the analysis yielding a response rate of 21.35% (101/473). The mean age was 23.97 (SD = 1.27), and it was not significantly associated with the DASS-21 mean score and any of the three subscales' mean scores. Of the 101 participants, 7.92% reported GPA between 2.0–2.5, 38.61% between 2.5–3.0, 33.66% between 3.0–3.5, and 19.80% between 3.5–4.0. Regarding the duration of preparation, most respondents (n = 62, 61.39%) spent 1–2 years, 7.92% spent more than 2 years, 11.88% spent 6 months-1 year, and 18.81% spent less than 6 months. Less than half of the respondents (n = 39, 38.61%) spent 30–60 h a week. Among others, 14.85% spent more than 60 h, 15.84% spent 15–30 h, and 30.69% spent less than 15 h. A substantial majority (n = 92, 91.09%) of the participants attended a preparatory course.

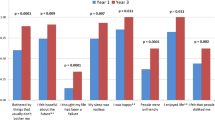

About half (n = 53, 52.48%) of the students considered their study insufficient, a little more than a quarter (n = 27, 26.73%) considered their study sufficient, and 20.79% were unsure regarding the sufficiency of their study. Although 29.70% never considered quitting studying, more than two third of students considered quitting studying (38.61% rarely, 20.79% often, 10.89% always). 34.65% of students used prescription psychiatric drugs or undergone psychotherapy, 31.68% used prescription stimulants to increase productivity, and 46.53% started using or increased the consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, or drugs during preparation for ESM. Most students were not mindful of their nutrition, did not get enough sleep, and did not set aside time for exercising. These variables and their association with the subscale scores are given in Table 1.

DASS-21 depression subscale

The attitude subscale showed high internal reliability (a = 0.84) with a mean score of 10.42 (7.48). In the univariate analysis (Table 1). attendance to preparatory courses (p = 0.026) and consideration of quitting studying (p = 0.005) were found to be statistically significant. The multivariate regression model (Table 2). showed that those who did not attend preparatory courses received lower scores than those who attended preparatory courses by 5.82 points [p = 0.046, coefficient = -5.82, 95% confidence interval [CI] = (-11.52) – (-0.10)]. Participants who never [p = 0.001, coefficient = -10.13, 95% CI (-15.82)—(-4.44)], rarely [p = 0.006, coefficient = -8.03, 95% CI (-13.73)—(-2.34)], or often [p = 0.029, coefficient = -6.87, 95% CI (-13.00)—(-0.73)] considered quitting studying had lower scores than those who stated always considering quit studying.

DASS-21 anxiety subscale

The anxiety subscale was internally reliable (a = 0.81), with a mean score of 14.55 (8.62). The univariate analysis (Table 1) revealed that participants who considered quitting studying (p < 0.001), used prescription psychiatric drugs, or underwent psychotherapy (p = 0.007), and were deprived of sufficient sleep (p = 0.039) had higher anxiety levels than others. In multivariate analysis (Table 2), respondents who always considered quitting studying had higher scores than those who never [p < 0.001, coefficient = -10.65, 95% CI (-15.41) – (-5.89)] or rarely [p = 0.017, coefficient = -6.04, 95% CI (-10.95) – (-1.12)] considered quitting studying. Lastly, medical students using prescription psychiatric drugs or receiving psychotherapy during the preparation for ESM had higher scores than those who did not [p = 0.03, coefficient = -3.35, 95% CI (-6.38) – (-0.33)].

DASS-21 stress subscale

The stress subscale showed high internal reliability (a = 0.86) with a mean score of 15.50 (8.18). In the univariate analysis (Table 1), we found statistical significance in the mean subscale scores for eight variables: duration of preparation (p = 0.013), attendance to a preparatory course (p = 0.041), consideration of quitting studying (p = 0.037), prescription psychiatric drugs usage or ongoing psychotherapy (p < 0.001), prescription stimulants usage (p = 0.004), setting aside time for oneself (p = 0.008), setting aside time for family or friends (p = 0.004), and having started to use or increased consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, or drugs (p = 0.004). The multivariate model (Table 2). showed that those who prepared for less than 6 months (p = 0.016, coefficient = 5.19, 95% CI 1.00 – 9.38) were more depressed than those who prepared for 1–2 years. Final year medical students who never [p < 0.001, coefficient = -10.95, 95% CI (-15.95) – (-5.95)], who rarely [p = 0.016, coefficient = -6.62, 95% CI (-12.00) – (-1.24)], and who often considered quitting studying [p = 0.011, coefficient = -7.08, 95% CI (-12.49) – (-1.67)] had lower scores compared to those who always considered quit studying. Last, participants who were deprived of sufficient sleep (p = 0.029, coefficient = 3.93, 95% CI 0.42 – 7.44) had higher anxiety levels than interns who got enough sleep.

Discussion

According to a narrative review of studies between 1990 and 2015, 35%-55% of medical students suffered emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and other burnout-related symptoms [37], supporting the studies unveiling that more than half of medical students experienced burnout [1, 16]. Furthermore, in a more recent study, the frequency of burnout syndrome among university students was estimated to be 55.4% for emotional weariness, 31.6% for cynicism, and 30.0% for academic efficacy [38]. Depression possibly came with underlying burnout, leading to more severe depression [23, 39, 40]. Previously reported depression rates in medical students seemed to be depending on the sample, measured at as high as 51.3% in one medical school in India, while it was 23.5% among German medical students [41, 42]. According to a study, the medical student anxiety level was at the 85th percentile compared to the age-matched peers in the general population [14, 43]. Severe anxiety mainly arose from medical licensing examinations [44]. One study found that 22% of medical students experienced "moderately high" to "extremely high" test anxiety [45].

Most studies in the literature of medical student mental wellness revolved around the medical students who prepared for USMLE. However, their results should not be generalized to the medical students preparing for different exams all around the world. This study is a step to relieve the need for new samples since our participants were medical students preparing for the ESM in Turkey. Thus, our research not only elucidates the link between medical student general psychological distress and the preparation period for the specialty exam in Turkey but also helps to understand whether the results are comparable to previous studies with different samples.

Our study found that the following variables are associated with final-year medical student mental wellness: attendance to preparatory courses, duration of preparation, consideration of quitting studying, and psychiatric drug usage/ongoing psychotherapy.

Most final-year medical students in Turkey wish to prepare for the ESM. According to a study, almost all final-year medical students attended commercial test preparation courses for the ESM [32]. In other words, final-year medical students wanted to allocate more time and effort to prepare for the ESM. It was consistent with our findings which demonstrate that more than half of the students considered their studies insufficient. Although most students attended preparatory courses for higher ESM scores, corresponding US studies showed that educational advancement provided by these courses was minimal or absent [46]. Despite this notorious fact, most students still opt for attending preparatory courses due to the anxiety associated with medical examinations in the US [47, 48]. Consistent with this data, attending preparatory courses for ESM was associated with poor mental wellness, as those who attended preparatory courses had higher scores on the depression subscale than those who did not. The first explanation is that medical students with psychological problems during preparation tended to attend preparatory courses rather than work alone. On the other hand, considering the hectic pace of the preparatory courses, medical students who attended these courses may experience psychological problems due to the extra stress burden they undertook after attending these courses.

In our study, students who spent less than 6 months preparing for ESM had higher stress levels than those who spent 1–2 years for the preparation. One reasonable explanation for that is insecurity. Insecurity caused by insufficient preparation might have led to elevated stress levels. On the other hand, our study revealed that stress levels were similar for medical students who considered their studies insufficient and those who did not. However, the term "insufficient" is controversial since some students are perfectionists and others are easily satisfiable. Hence, medical students who considered their studies insufficient did not necessarily spend less time studying than those who did not. Feeling insufficient to pass the specialty exam may result in elevated stress, whereas feeling insufficient to acquire the best positions may not relate to stress levels. Further studies should investigate the role of insecurity caused by insufficient preparation on medical student stress.

Final-year medical students who considered quitting studying got higher scores on all subscales. First, depressed interns may not have had enough motivation to study anymore since depression is known to cause reluctance. Second, medical students who did not trust their medical skills may have considered quitting studying due to anxiety. In addition, high anxiety exacerbated by harsh conditions and low salaries may have resulted in quitting studying for the ESM and looking for other opportunities. For example, most medical students (73.27%) reported that they would like to work abroad in the future. Lastly, interns who could not take the psychological burden caused by the high-stress environment might have tended to consider quitting studying more. In short, final-year medical students with higher depression, anxiety, and stress levels considered quitting studying more often than others.

In our study, we discovered that 34.65% of students used prescription psychiatric drugs or received psychotherapy. Furthermore, according to multivariate analysis, medical students who used prescription psychiatric drugs or received psychotherapy while preparing for ESM had higher anxiety subscale scores than those who did not. According to Ministry of Health statistics, antidepressant use in Turkey in 2020 was 49 per 1000 individuals [49]. Although we have no data on the number of individuals receiving psychotherapy in Turkey, it is safe to say that antidepressant use is more prevalent among our cohort than among the general population. Moreover, Fasanella et al. found that the prevalence of psychotropic drug use among first- to final-year medical school students at a private university in Brazil was 30.4% [50]. In a separate study, 2.4% of 4345 medical students from 35 French medical schools reported using antidepressants, 5.4% reported using anxiolytics, and 6.5% reported psychiatric or psychotherapeutic follow-up [51]. Consequently, the high rate of antidepressant consumption and psychotherapeutic follow-up in our cohort may be explained by ESM preparation, which is further supported by another study indicating a gradual decline in mental health during medical school [29]. Further research is required to establish the link between ESM preparation and the high rate of antidepressant consumption and psychotherapeutic follow-up, specifically by assessing the antidepressant consumption and psychotherapeutic follow-up of doctors in residency training in Turkey.

In our study, demographic variables and general psychological distress were not correlated. To conduct a detailed statistical analysis, we assessed the impact of GPA on mental wellness and found no correlation. Being mindful of nutrition and setting aside time for exercising were demonstrated to be irrelevant to mental wellness, but those who could not get enough sleep had higher stress levels. Although almost half of the students started using or increased their consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, or drugs and could not set aside time for themselves and their families or friends, these variables were not related to poor mental wellness. Surprisingly, final-year medical students who believed they would not get the worth of their study had similar results on all subscales to those who believed they would.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, the response rate among the targeted cohort was low (21.35%). The medical school from which the sample was derived is one of the top medical schools in Turkey. Therefore, the participants' lifestyles, preferences, and priorities might have been associated with the characteristics of high achievers. Further studies with samples from different schools would help to compare the data and evaluate the accuracy of our study and the generality of our conclusions. Data were collected with a questionnaire based on the interns' self-declarations. There was no external validation regarding the variables such as GPA, prescription psychiatric drugs, or prescription stimulants. In addition, although we attempted to evaluate the mental wellness of the students, we were only able to assess their depression, anxiety, and stress level, which are important components of mental wellness but not the entirety of it.

In this study, we only included final-year medical students. However, most medical students usually start to prepare for the ESM in their earlier years. Further studies may include both 5th-year and final-year medical students. Lastly, this study was conducted in an environment where the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were still on.

Conclusion

In Turkey, medical students prepare for the ESM in a high-stress environment. Most of them may become more depressed, anxious, and stressed during the preparation. Our survey assessed final-year medical student general psychological distress during the preparation of ESM. We found four variables were associated with mental wellness: attendance to preparatory courses, duration of preparation, consideration of quitting studying, and psychiatric drug usage/ongoing psychotherapy. With its distinguished sample, this study will be an excellent source for researchers and authorities who aim to improve medical student mental wellness.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014;89:443–51.

Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1358–67.

Garr DR, Lackland DT, Wilson DB. Prevention education and evaluation in U.S. medical schools: a status report. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2000;75(7):14–21.

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet Lond Engl. 2009;374:1714–21.

Pfifferling J-H, Gilley K. Overcoming compassion fatigue. Family practice management. 2000;7:39.

Greenburg DL, Durning SJ, Cruess DL, Cohen DM, Jackson JL. The prevalence, causes, and consequences of experiencing a life crisis during medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22:85–92.

Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The Business Case for Investing in Physician Well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1826–32.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325.

Wasson LT, Cusmano A, Meli L, Louh I, Falzon L, Hampsey M, et al. Association Between Learning Environment Interventions and Medical Student Well-being: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016;316:2237–52.

Ishak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10:242–5.

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2214–36.

Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, Moutier C, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Patterns of distress in US medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33:834–9.

Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, Raj KS, Murphy ML, Bohman B, et al. What Do We Mean by Physician Wellness? A Systematic Review of Its Definition and Measurement. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Resid Train Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:94–108.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Other Indicators of Psychological Distress Among U.S. and Canadian Medical Students. Acad Med. 2006;81:354–73.

Cullen MW, Reed DA, Halvorsen AJ, Wittich CM, Kreuziger LMB, Keddis MT, et al. Selection Criteria for Internal Medicine Residency Applicants and Professionalism Ratings During Internship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:197–202.

Brazeau CMLR, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, Massie FS, Eacker A, Moutier C, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014;89:1520–5.

Schwenk TL, Davis L, Wimsatt LA. Depression, stigma, and suicidal ideation in medical students. JAMA. 2010;304:1181–90.

Chen Z, Wang B, Lin Y, Luo C, Li F, Lu S, et al. Research Status of Job Satisfaction of Medical Staff and its Influencing Factors. J Serv Sci Manag. 2021;14:45–57.

Yusoff MSB, Mat Pa MN, Esa AR, Abdul Rahim AF. Mental health of medical students before and during medical education: A prospective study. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2013;8:86–92.

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1681–94.

McLuckie A, Matheson KM, Landers AL, Landine J, Novick J, Barrett T, et al. The Relationship Between Psychological Distress and Perception of Emotional Support in Medical Students and Residents and Implications for Educational Institutions. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Resid Train Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:41–7.

Borst JM, Frings-Dresen MHW, Sluiter JK. Prevalence and incidence of mental health problems among Dutch medical students and the study-related and personal risk factors: a longitudinal study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;28:349–55.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–41.

Lee J, Graham AV. Students’ perception of medical school stress and their evaluation of a wellness elective. Med Educ. 2001;35:652–9.

Radcliffe C, Lester H. Perceived stress during undergraduate medical training: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2003;37:32–8.

Cortes-Penfield NW, Khazanchi R, Talmon G. Educational and Personal Opportunity Costs of Medical Student Preparation for the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 Exam: A Single-Center Study. Cureus. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10938.

Khan R, Lin JS, Mata DA. Addressing Depression and Suicide Among Physician Trainees. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72:848.

Tackett S, Jeyaraju M, Moore J, Hudder A, Yingling S, Park YS, et al. Student well-being during dedicated preparation for USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX Level 1 exams. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:16.

Paro HBMS, Morales NMO, Silva CHM, Rezende CHA, Pinto RMC, Morales RR, et al. Health-related quality of life of medical students. Med Educ. 2010;44:227–35.

Duica L, Talau R, Nicoara D, Dinca L, Turcuc J, Talu G. “ Stress-Anxiety-Coping” triad in medical students. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology. 2012;2.

Reed DA, Shanafelt TD, Satele DW, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, et al. Relationship of pass/fail grading and curriculum structure with well-being among preclinical medical students: a multi-institutional study. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86:1367–73.

Turan S, Üner S. Preparation for a Postgraduate Specialty Examination by Medical Students in Turkey: Processes and Sources of Anxiety. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:27–36.

Six Dimensions of Wellness - National Wellness Institute. 2020. 542 https://nationalwellness.org/resources/six-dimensions-of-wellness/. Accessed 8 Jul 2022.

Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 2):227–39.

Hekimoglu L, Altun ZO, Kaya EZ, Bayram N, Bilgel N. Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of the 42 Item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Dass-42) in a Clinical Sample. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44:183–98.

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 20 Nov 2022.

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50:132–49.

Rosales-Ricardo Y, Rizzo-Chunga F, Mocha-Bonilla J, Ferreira JP. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in university students: A systematic review. Salud Ment. 2021;44:91–102.

Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident Wellness Matters: Optimizing Resident Education and Wellness Through the Learning Environment. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2015;90:1246–50.

Langade D, Modi PD, Sidhwa YF, Hishikar NA, Gharpure AS, Wankhade K, et al. Burnout Syndrome Among Medical Practitioners Across India: A Questionnaire-Based Survey. Cureus. 8:e771.

Iqbal S, Gupta S, Venkatarao E. Stress, anxiety and depression among medical undergraduate students and their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:354–7.

Rueckert K-K. Quality of Life and Depression in German Medical Students at foreign universities. In: RSU International Conference Health and Social Science. 2016. p. 168.

Vitaliano PP, Maiuro RD, Russo J, Mitchel ES. Medical student distress. A longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:70–6.

Powell DH. Behavioral treatment of debilitating test anxiety among medical students. J Clin Psychol. 2004;60:853–65.

Green M, Angoff N, Encandela J. Test anxiety and United States Medical Licensing Examination scores. Clin Teach. 2016;13:142–6.

McGaghie WC, Downing SM, Kubilius R. What is the impact of commercial test preparation courses on medical examination performance? Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:202–11.

Werner LS, Bull BS. The effect of three commercial coaching courses on Step One USMLE performance. Med Educ. 2003;37:527–31.

Strowd RE, Lambros A. Impacting student anxiety for the USMLE Step 1 through process-oriented preparation. Med Educ Online. 2010;15.

Ülgü MM, Birinci Ş. THE MINISTRY of HEALTH of TÜRKİYE HEALTH STATISTICS YEARBOOK 2020. https://dosyasb.saglik.gov.tr/Eklenti/43400,siy2020-eng-26052022pdf.pdf?0. Accessed 19 Jan 2023.

Fasanella NA, Custódio CG, Cabo JS, do, Andrade GS, Almeida FA de, Pavan MV,. Use of prescribed psychotropic drugs among medical students and associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J Rev Paul Med. 2022;140:697–704.

Fond G, Bourbon A, Boucekine M, Messiaen M, Barrow V, Auquier P, et al. First-year French medical students consume antidepressants and anxiolytics while second-years consume non-medical drugs. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:71–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK conceived the topic of the study. MK, MH and ZO were involved in designing the study and analyzing data. BU, EO, and BK were involved in data collection. MK, MH, and BBO were involved in drafting the manuscript, listed in decreasing order of their contributions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been approved by the ethics committee at the Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Faculty of Medicine on the 24th April 2022. An informed consent form was signed electronically by all participants and anonymity was assured. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Before starting the survey, participants were provided a summary of the study, explaining its purpose, its scientific and academic nature, terms of anonymity, and confidentiality. Participants consented to their anonymized data being used by checking a box.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karabacak, M., Hakkoymaz, M., Ukus, B. et al. Final-year medical student mental wellness during preparation for the examination for specialty in Turkey: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Med Educ 23, 79 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04063-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04063-0