Abstract

Background

Currently, no standardized methods exist to assess the geriatric skills and training needs of internal medicine trainees to enable them to become confident in caring for older patients. This study aimed to describe the self-reported confidence and training requirements in core geriatric skills amongst internal medicine residents in Toronto, Ontario using a standardized assessment tool.

Methods

This study used a novel self-rating instrument, known as the Geriatric Skills Assessment Tool (GSAT), among incoming and current internal medicine residents at the University of Toronto, to describe self-reported confidence in performing, teaching and interest in further training with regard to 15 core geriatric skills previously identified by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Results

190 (75.1%) out of 253 eligible incoming (Year 0) and current internal medicine residents (Years 1–3) completed the GSAT. Year 1–3 internal medicine residents who had completed a geriatric rotation reported being significantly more confident in performing 13/15 (P < 0.001 to P = 0.04) and in teaching 9/15 GSAT skills (P < 0.001 to P = 0.04). Overall, the residents surveyed identified their highest confidence in administering the Mini-Mental Status Examination and lowest confidence in assessing fall risk using a gait and balance tool, and in evaluating and managing chronic pain.

Conclusion

A structured needs assessment like the GSAT can be valuable in identifying the geriatric training needs of internal medicine trainees based on their reported levels of self-confidence. Residents in internal medicine could further benefit from completing a mandatory geriatric rotation early in their training, since this may improve their overall confidence in providing care for the mostly older patients they will work with during their residency and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rapid growth in the number of persons aged 65 years and older has been well documented, as have concerns of how global healthcare systems will respond to meet the complex medical needs of growing aging populations [1,2,3]. Older patients often present with unique healthcare considerations that include interacting comorbidities [4], increased vulnerability to the adverse effects of polypharmacy [5, 6], frailty [7] and a poorer prognosis for different conditions in comparison with younger patients [8,9,10]. While it would be ideal if the number of geriatricians corresponded with specialist-to-aging-population requirements, the current and future predicted number of geriatricians does not align with existing and future needs [11, 12]. As such, there has been growing recognition of the need to ensure that all physicians working with older persons are confident and capable of delivering appropriate geriatric care [13,14,15,16]. Given that the majority of care general internists provide is to older adults [17,18,19], it is crucial that internal medicine residency programs focus on preparing the next generation of physicians to address the specific needs of older patients [20, 21].

With a rapidly aging population, it is reasonable to expect that all internal medicine specialists graduating from residency training programs acquire an appropriate amount of knowledge, skill and exposure to caring for older adults, so they can be confident in providing care for them. Despite this, current literature suggests that internal medicine physicians may not feel comfortable in some areas of geriatric medicine, such as deprescribing guideline-recommended therapies to avoid polypharmacy [22], addressing frailty [16] and managing polymorbidity and complexity [23]. To assist internal medicine residents, a variety of novel geriatric training programs and curriculums have been developed [24,25,26,27,28]. Historically, these programs have often been evaluated through knowledge-based testing or surveys of residents’ experiences [24, 27,28,29]. Measuring a trainees’ self-confidence in the performance of core geriatric skills is also important, as their level of self-confidence can potentially predict performance success, indicate their satisfaction with their training and impact career choices [30,31,32]. Whereas validated tools measuring residents’ self-confidence exist for other specialties like surgery [33, 34], there is no such tool for geriatric medicine. In the absence of a robust, standardized method to assess the self-reported confidence of internal medicine trainees in performing or teaching core geriatric skills, it is difficult to ascertain areas for improvement.

This study examined the use of a self-rating instrument, known as the Geriatric Skills Assessment Tool (GSAT) (Fig. 1), among a sample of internal medicine residents in Toronto, Ontario. This tool was developed by Jamshed & Sinha [35] to establish learning needs by assessing self-confidence in performing and teaching geriatric skills and determining interest in acquiring further training in geriatric skills [35, 36].

Methods

Study aims and design

This study aimed to describe the self-reported confidence and training needs of internal medicine residents with regard to core geriatric skills, using the GSAT. The specific objectives were to: 1) identify the self-reported confidence of internal medicine residents in performing core geriatric skills; and 2) identify the self-reported geriatric medicine training needs of internal medicine residents. A quantitative study using a non-experimental design was utilized. A novel survey (GSAT) was implemented to answer the research objectives.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board and was conducted in accordance with all regulations (REB #11–0124-E). All participants provided informed consent by completing the survey.

Setting

This study explored patterns of confidence and training needs amongst internal medicine residents at the University of Toronto (UT). UT is a world-leading educational institution and the sole medical school for numerous major hospitals in Toronto, Canada’s most populous city. It runs the largest internal medicine residency program in Canada and is in the minority of programs mandating the completion of a rotation in geriatrics, which occurs between years 1 to 3 at a time of the trainees’ choosing [37, 38]. During this rotation, internal medicine residents are required to spend a minimum of one block (~ 4 weeks) in geriatric medicine. This block incorporates providing inpatient and outpatient geriatric medicine consultations and follow-up care, scheduled and informal teaching sessions.

Participants and data collection

All incoming (Year 0) and current (Years 1–3) core internal medicine residents at UT were invited to complete an anonymous, electronic SurveyMonkey® or paper-based structured survey from February to June 2012. This captured existing internal medicine residents towards the end of their current training year, as well as the newly selected group of incoming internal medicine residents who were final-year medical students at the time of survey distribution. The survey assessed core geriatric skills competencies using the GSAT and collected baseline demographic and training history information.

Survey invitations were delivered via personalized email and an in-person presentation during an internal medicine academic teaching session. Response rates were optimized through five follow-up email invitations. Participants were incentivized in the form of a random draw for gift cards offered to all who submitted a completed survey. Consent was implied if participants proceeded with survey submission.

Geriatric skills assessment tool (GSAT)

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certifies general internists and medical subspecialists who demonstrate the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes essential for patient care according to their standards of examination. The GSAT is a cross-sectional educational needs assessment tool developed to assess a general internist’s confidence in performing and teaching, as well as their interest in further training, with regard to 15 ABIM-identified core geriatric clinical skills [35, 36]. While no longer publicly accessible through their website, the ABIM previously published 15 minimum geriatric medicine clinical competencies expected by the end of core residency training in internal medicine. These covered fundamental geriatric care domains such as medication management, cognition, comorbidity and end-of-life care. The ABIM clinical competencies also covered core geriatric care domains found in the 26 minimum geriatric competencies established by a working group of educators from internal medicine and family medicine residency programs in 2007 [39]. To the best of our knowledge, to date, these minimum competencies have not changed.

Freely available on the Portal of Geriatrics Online Education, the GSAT is the first self-rating instrument designed to assess geriatric skills in postgraduate internal medicine trainees and specialists. It has been used to assess the skills of internal medicine teaching faculty and residents at academic teaching hospitals in both Canada and the US [36, 40]. The GSAT is a versatile tool that can be easily used to examine several select competencies of interest in an individual program.

The GSAT uses a modified 4-level (low to high) Likert scale [41], through which respondents are asked to self-report their confidence in performing and teaching 15 geriatric skills, as well as their interest in pursuing further training in them [35, 36, 40]. The validity and reliability of the GSAT were previously demonstrated with internal medicine residents and general internists in an academic hospital setting with an established Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.96 [36, 40].

Statistical analysis

The GSAT data were analyzed with SAS software® using descriptive statistical methodologies to evaluate the trainees’ responses [42]. For the analysis, the 4-level Likert scale responses were grouped into ‘low’ and ‘high’ responses. A score of 1 or 2 on the Likert scale was considered ‘low’ and 3 or 4 considered ‘high’. Mean scores were determined from the grouped scores. Chi-square tests were then used to determine any significant statistical differences in the mean scores between the various demographic factors collected. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for our analyses [43].

Results

190 (75.1%) out of the 253 eligible incoming (Year 0) and current internal medicine residents (Years 1–3) completed the survey and are further characterized in Table 1. A minimum and maximum response rate of 67.2 and 81.8% was achieved across the four groups of trainees. 77.4% of the respondents completed medical school in Canada, while the remaining attended international medical schools across 13 different countries. The overall reported interest in becoming specialists in general internal medicine and geriatrics was 17.9 and 2.6% respectively. 34.2% of Year 1 to 3 residents reported having completed a formal training rotation in geriatrics at the time of the survey. The proportion of Year 1, 2 and 3 residents with reported completion of a geriatric rotation was 4.2, 21.3 and 85.4% respectively.

Summary of findings around geriatric skills

There was no gender variation other than the observation that female respondents showed a higher interest in acquiring further training about situations where diagnosis and treatment in older adults should be modified (GSAT Skill 3, P = 0.03). Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1 provides the Chi-square results examining differences in the mean scores around the three domains of the 15 geriatric skills observed concerning various demographic factors.

Significant GSAT score differences were found in several selected domains for the respondents’ place of medical school training, prior completion of a geriatric training rotation, number of postgraduate training years, and identified future subspecialty area of interest. Respondents who attended a medical school in Canada were significantly more confident in assessing functional capacity (GSAT Skill 2, P = 0.01), administering the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [44] (GSAT Skill 8, P = 0.004) and conducting discussions regarding goals of care (GSAT Skill 13, P = 0.01), compared with respondents who completed medical school outside of Canada. They were also significantly more confident in teaching 5/15 GSAT Skills (P < 0.001 to P = 0.03).

Year 1–3 respondents who had completed a formal rotation in geriatrics during their residency reported a significantly higher degree of confidence in performing 13/15 GSAT Skills (P < 0.001 to P = 0.04) and in teaching 9/15 GSAT Skills (P < 0.001 to P = 0.04), compared to those who had not completed a geriatrics rotation.

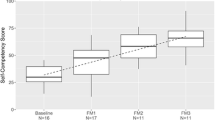

The number of postgraduate years in residency training significantly impacted respondents’ confidence in performing and teaching geriatric skills. Incoming residents (Year 0) were more confident in performing 8/15 and teaching 6/15 GSAT Skills when compared with Year 1 residents. Year 2 and Year 3 residents showed higher levels of confidence in performing and teaching 11/15 and 12/15 GSAT Skills respectively compared with lower year residents. There were 4/15 GSAT skills in which Year 1 or 2 residents who had completed a formal rotation in geriatrics showed significantly greater confidence in performing compared to Year 3 residents who had not completed a geriatric rotation. These included identifying medications that should be used with caution in older adults (GSAT Skill 4, P = 0.05), assessing an older patient’s fall risk using a gait and balance assessment tool (GSAT Skill 7, P = 0.006), knowing the indications of and risks associated with antipsychotic medications (GSAT Skill 10, P = 0.02) and evaluating and managing chronic pain in older adults (GSAT Skill 12, P < 0.001). Tables 2 and 3 provide mean Likert scores related to confidence in performing and teaching GSAT Skills.

Differences were noted in the collective self-rating scores between residents interested in general internal medicine as a future subspecialty versus residents who were reportedly undecided or interested in other subspecialties across all years of training. Those interested in general internal medicine expressed greater confidence in performing 5/15 GSAT Skills (P = 0.002 to P = 0.05, see Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1). They were also significantly more confident in teaching skills to identify medications that should be used with caution in older adults (GSAT Skill 4, P = 0.02) and recognizing an older person’s risk of falls (GSAT Skill 6, P = 0.02). However, these internal medicine residents were less confident in teaching the evaluation and management of chronic pain in older adults when compared with all other residents (GSAT Skill 12, P = 0.04). Our results did not show that residents interested in geriatrics expressed a significantly greater interest to pursue further training in core geriatric skills, compared with other residents. Residents who were undecided about their future subspecialty were less confident in differentiating normal from abnormal aging (GSAT Skill 1, P = 0.05) and identifying situations where standard diagnosis and treatment in older adults should be modified (GSAT Skill 3, P = 0.003).

Table 4 lists the top GSAT skills in which residents reported both their highest and lowest mean scores for their confidence in performing, teaching and interest in further training. Overall, trainees identified their highest confidence in administering the MMSE (GSAT Skill 8, mean Likert score 3.48), performing a goal of care discussion (GSAT Skill 13, mean Likert score 3.09) and differentiating between delirium, dementia and depression (GSAT Skill 9, mean Likert score 3.04). Trainees reported their lowest confidence in assessing fall risk using a gait and balance tool (GSAT Skill 7, mean Likert score 2.13), evaluating and managing chronic pain (GSAT Skill 12, mean Likert score 2.41) and identifying situations where standard diagnosis and treatment should be modified (GSAT Skill 3, mean Likert score 2.46). The GSAT skills in which trainees reported lower confidence in performing were different from the skills in which they reported the highest interest in further training. Trainees reported their highest interest in further training for identifying medications to be used with caution (GSAT Skill 4, mean Likert score 3.41), conducting goals of care discussions (GSAT Skill 13, mean Likert score 3.4) and conducting end-of-life care discussions (GSAT Skill 14, mean Likert score 3.34).

When examining the responses of Year 3 residents who were in their final year of internal medicine training, their lowest level of confidence was in assessing an older patient’s fall risk using a screening gait and balance assessment tool (GSAT Skill 7, mean Likert score 2.3) and in evaluating and managing chronic pain in older adults (GSAT Skill 12, mean Likert score 2.7). The two GSAT skills with the reported highest interest in acquiring further training were knowing indications and risks associated with antipsychotic medications (GSAT Skill 10, mean Likert score 3.2) and managing chronic pain in older adults (GSAT Skill 12, mean Likert score 3.2) (see Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Several educational strategies have been devised to improve the ability of internal medicine residents to provide appropriate geriatric care. However, despite numerous endeavors to evaluate the impact of such strategies, no existing study has used the GSAT for this purpose. This study is the largest known survey of incoming and current internal medicine residents about their confidence in performing and teaching, as well as interest in further training, with regard to 15 previously identified ABIM core geriatric skills and competencies. Furthermore, this study’s collection of additional demographic and medical training information enables an understanding of additional factors that may influence the nature of the responses given. The results of this study may be used to inform future research and educational efforts, given that information about the training needs and confidence of internal medicine residents in the field of geriatrics is sparse. This preliminary study highlights perceived gaps in knowledge and skills that may inform professional development approaches for future internal medicine residents and their educators.

Our findings clearly demonstrate that both the overall time spent in postgraduate internal medicine residency training and prior exposure to a formal training rotation in geriatrics significantly improved the self-reported confidence of trainees in performing core geriatric skills. This finding has been confirmed by previous studies, which found the overall time spent in postgraduate residency training improved the self-reported confidence of trainees in surgery [45], family medicine [46] and obstetrics [47]. While growth in confidence appeared to escalate linearly with years of residency training, the incoming (Year 0) trainees declared a slightly higher level of confidence than the Year 1 trainees. This correlates with other medical education studies that document a phenomenon where junior trainees may be unaware of their knowledge gaps and overestimate their abilities [48,49,50,51]. Nevertheless, it is clear that as residents progress through their training, they build their confidence in caring for older patients. We note a high degree of association between exposure to geriatric medicine and confidence in caring for older adults; a phenomenon that has largely been studied in the context of undergraduate medical education (e.g., [52]). Most internal medicine residents in this study chose to complete their mandatory geriatric rotation late in residency, with only 21.3% of second-year residents having completed this compared with 85.4% of third-year residents. Of note, completing a formal training rotation in geriatrics had a significant positive impact on trainees’ self-reported confidence around performing 13/15 GSAT skills, compared with trainees who had not yet completed their geriatrics rotation. Additionally, first- and second-year residents who had completed a geriatric rotation demonstrated a greater level of confidence in their knowledge of some geriatric skills compared with third-year residents who had not yet completed this, despite the first-year residents having less overall clinical experience. This suggests that both exposure to geriatric medicine and general clinical experience from accumulating years of residency training increase self-reported confidence in performing geriatric skills. Other authors have similarly noted that an increase in experience and exposure to clinical cases in various specialties (e.g., family medicine, surgery, oncology) can result in increased resident confidence in these areas [31, 53, 54]. Our findings suggest that, in some cases, completing a formal geriatrics rotation may be more crucial in the development of a resident’s geriatric skills than cumulative years of residency experience, supporting the argument for making a geriatrics training curriculum mandatory for all internal medicine residents. Whereby residents identified low confidence, such as in the areas of deprescribing, chronic pain management and fall risk assessment, interprofessional educational experiences with pharmacy and physiotherapy trainees may be an innovative way to meet these training needs [55, 56]. Interprofessional education can also be facilitated through technology, such as having virtual patients [57, 58]. Having interprofessional educators and colleagues has also been found to better prepare residents for collaborative practice in the care of their geriatric patients and increase their confidence about specific geriatric syndromes and practices [59].

Considering that there is still no mandatory national geriatric training requirement for internal medicine residents in Canada [60, 61], and only 43% of internal medicine residents in the United States have previously reported feeling confident in their geriatric skills [62], this study’s findings reinforce the potential benefits of incorporating geriatric training into all internal medicine residency programs. Despite 77% of the residents in our study having graduated from a Canadian medical school, it was clear that they were significantly more confident in performing and teaching core geriatric skills compared to their internationally trained colleagues. Given that geriatrics is a relatively new specialty, some countries do not incorporate geriatrics into their medical school curriculum, which may account for this finding [63]. Our findings may reflect the concerted efforts undertaken in Canada [54] to identify core-training competencies for medical students and encourage the implementation of training opportunities in medical schools to support the better provision of geriatric care [55, 64,65,66,67]. This study highlights not only the importance of dedicated training to build residents’ confidence in essential geriatric skills, but suggests that exposing trainees to formal geriatrics training early in their residencies may help them to more quickly master these skills.

When examining respondents’ future subspecialty areas of interest, those who expressed an interest in becoming a general internist were more likely to report greater confidence in performing and teaching most geriatric skills, compared to those who were undecided. While it may be expected that those declaring a future interest in geriatrics should have had the greatest self-reported confidence, there was insufficient statistical power to confirm or refute this expectation as only 2.6% of the respondents fell into this category. As a result, future studies are encouraged to explore the association between self-reported confidence in geriatrics and career-practice preferences during internal medicine residencies.

By evaluating self-reported confidence with and interest in learning about various geriatric skills, this study shows how the GSAT can be used to inform the design of a geriatric medicine training curriculum that is tailored to the learning needs of internal medicine residents. For example, respondents in our study had the highest reported confidence in both performing and teaching, as well as their lowest interest in further training on, how to administer the MMSE (GSAT Skill 8), suggesting that further education in this area is not required. Additionally, a topic that third-year residents expressed great interest in receiving further training in, was evaluating and managing chronic pain in older adults (GSAT Skill 12). This was the same geriatric skill in which first and second-year residents who had completed a rotation in geriatrics were significantly more confident in managing than third-year residents who had not completed a geriatrics rotation. This type of information may prompt educators to incorporate training on chronic pain earlier in residency to more proactively and adequately address this training gap. Identifying residents’ learning interests and knowledge gaps, as evidenced by low self-reported confidence levels, can also be used to make improvements to internal medicine residency program curricula.

Study limitations

As a cross-sectional, single-site study providing a descriptive snapshot of UT internal medicine residents, our findings have training- and location-specific implications that may not be transferable to other programs that vary in size, geographical location, curriculum orientation, and culture. However, it is important to note that our survey achieved a 75% overall response rate and was conducted in one of the largest internal medicine resident cohorts in North America, with trainees who had completed undergraduate training in over 38 medical schools across 14 countries around the world. Further research is needed to develop a broader understanding of the geriatric training needs and applicability of the GSAT in determining these amongst internal medicine residents in other settings. A further limitation is that the GSAT is currently not a validated tool, despite being used in previous research [36], and although correlations were identified between the variables we assessed, the study and survey itself does not allow us to establish causal relationships. It is also important to note that we have not established any connection between the perceived confidence level and the actual geriatric medicine skill level of the residents we surveyed. Finally, data collected from this study is now several years old. It is likely that internal medicine residency programs, including that at UT, have changed over this time. The results of and conclusions drawn from this study may have had a greater impact, particularly on local practice, had they been published in closer temporal proximity to when it was conducted. Nonetheless, highlighting the important role a needs assessment can potentially have to improve residency training programs, and demonstrating how the GSAT can be used to achieve this for geriatric medicine, still remains highly relevant to this day.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the value of a needs assessment, such as the GSAT, in the improvement of postgraduate medical curricula. Using the GSAT amongst all UT internal medicine residents, our findings suggest that the inclusion of a formal rotation in geriatrics, particularly early on in training, significantly improves residents’ confidence in performing and teaching multiple core geriatric skills. Medical curricula designers should consider incorporating a mandatory geriatric rotation for all internal medicine residents. Future research is encouraged to consider the applicability of the GSAT in determining training needs amongst internal medicine residents in other settings, such that this information can be used to further refine recommendations for internal medicine training.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GSAT:

-

Geriatric Skills Assessment Tool

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Exam

References

Banerjee D. ‘Age and ageism in COVID-19’: elderly mental health-care vulnerabilities and needs. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102154.

Bone AE, Gomes B, Etkind SN, Verne J, Murtagh FE, Evans CJ, et al. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat Med. 2018;32(2):329–36.

Sleeman KE, De Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883–e92.

McGilton KS, Vellani S, Yeung L, Chishtie J, Commisso E, Ploeg J, et al. Identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–33.

Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan EC, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(12):1185–96.

Pazan F, Wehling M. Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(3):443–52.

Kokorelias KM, Cronin SM, Munce SE, Eftekhar P, McGilton KS, Vellani S, et al. Conceptualization of frailty in rehabilitation interventions with adults: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022:1–37.

Gómez-Belda AB, Fernández-Garcés M, Mateo-Sanchis E, Madrazo M, Carmona M, Piles-Roger L, et al. COVID-19 in older adults: what are the differences with younger patients? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(1):60–5.

Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, et al. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(1):49–58.

Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK biobank participants. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(7):e323–e32.

Basu M, Tracy Cooper KK, Hogan DB, Morais JA, Molnar F, Lam RE, et al. Updated inventory and projected requirements for specialist physicians in geriatrics. Can Geriatr J. 2021;24(3):200.

Hurria A, High KP, Mody L, McFarland Horne F, Escobedo M, Halter J, et al. Aging, the medical subspecialties, and career development: where we were, where we are going. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(4):680–7.

Donelan K, Chang Y, Berrett-Abebe J, Spetz J, Auerbach DI, Norman L, et al. Care management for older adults: the roles of nurses, social workers, and physicians. Health Aff. 2019;38(6):941–9.

Bacsu J, Mateen FJ, Johnson S, Viger MD, Hackett P. Improving dementia care among family physicians: from stigma to evidence-informed knowledge. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(4):340.

Molnar F, Frank CC. Optimizing geriatric care with the GERIATRIC 5Ms. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(1):39.

Cesari M, Marzetti E, Thiem U, Pérez-Zepeda MU, Van Kan GA, Landi F, et al. The geriatric management of frailty as paradigm of “the end of the disease era”. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:11–4.

Nagamine M, Jiang HJ, Merrill CT. Trends in elderly hospitalizations, 1997–2004. Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) statistical briefs: (US). USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

Edlund A, Lundström M, Karlsson S, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. Delirium in older patients admitted to general internal medicine. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19(2):83–90.

Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, Blaum CS, Dodson JA, Green AR, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American geriatrics society guiding principles on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):665–73.

Sedhom R, Sedhom D, Barile D. Meeting geriatric competencies: are internal medicine residency programs in New Jersey meeting expectations for quality care in older adults. SAGE Open. 2019;9(1):2158244019827678.

Landefeld CS, Callahan CM, Woolard N. General internal medicine and geriatrics: building a foundation to improve the training of general internists in the care of older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(7):609–14.

Djatche L, Lee S, Singer D, Hegarty S, Lombardi M, Maio V. How confident are physicians in deprescribing for the elderly and what barriers prevent deprescribing? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):550–5.

Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. The quality of outpatient care delivered to adults in the United States, 2002 to 2013. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1778–90.

Sedhom R, Barile D. Can webinar-based education improve geriatrics training in internal medicine residency programs? Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):606.

Southerland LT, Lo AX, Biese K, Arendts G, Banerjee J, Hwang U, et al. Concepts in practice: geriatric emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(2):162–70.

Lim SYS, Koh EYH, Tan BJX, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LK. Enhancing geriatric oncology training through a combination of novice mentoring and peer and near-peer mentoring: a thematic analysis of mentoring in medicine between 2000 and 2017. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(4):566–75.

Miller RK, Michener J, Yang P, Goldstein K, Groce-Martin J, True G, et al. Effect of a community-based service learning experience in geriatrics on internal medicine residents and community participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):E130–E4.

Siegler EL, Jalali C, Finkelstein E, Ramsaroop S, Ouchida K, Carmen TD, et al. Assessing effectiveness of a geriatrics rotation for second-year internal medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):521–5.

Ahmed NN, Farnie M, Dyer CB. The effect of geriatric and palliative medicine education on the knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):143–7.

Bucholz EM, Sue GR, Yeo H, Roman SA, Bell RH, Sosa JA. Our trainees’ confidence: results from a national survey of 4136 US general surgery residents. Arch Surg. 2011;146(8):907–14.

Fillmore WJ, Teeples TJ, Cha S, Viozzi CF, Arce K. Chief resident case experience and autonomy are associated with resident confidence and future practice plans. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(2):448–61.

Wojcik BM, McKinley SK, Fong ZV, Mansur A, Bloom JP, Amari N, et al. The resident-run minor surgery clinic: a four-year analysis of patient outcomes, satisfaction, and resident education. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(6):1838–50.

Geoffrion R, Lee T, Singer J. Validating a self-confidence scale for surgical trainees. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35(4):355–61.

Satterwhite T, Son J, Carey J, Echo A, Spurling T, Paro J, et al. The Stanford microsurgery and resident training (SMaRT) scale: validation of an on-line global rating scale for technical assessment. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:S84–S8.

Jamshed N, Sinha S. Geriatric skills assessment tool (GSAT) 2013 [Available from: https://pogoe.org/productid/20769.

Jamshed N, Mete M, Padmore J, Sinha S, editors. Identifying training needs of internal medicine faculty in geriatrics with a novel geriatrics skills assessment tool (GSAT). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2010.

The Time Higher Education. Best universities for medicine 2022 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/best-universities-medicine.

Shorter E. Partnership for excellence: medicine at the university of Toronto and academic hospitals. Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2013.

Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, Lundebjerg MN, Medina-Walpole A, Sauvigne K, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):373–83.

Jamshed N, Zeballos P, Sinha S, editors. Development and validation of a novel geriatric skills assessment tool (GSAT) to identify training needs of internal medicine residents and faculty. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. USA: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2012.

Croasmun JT, Ostrom L. Using Likert-type scales in the social sciences. J Adult Educ. 2011;40(1):19–22.

Cody R. SAS statistics by example. USA: SAS Institute; 2011.

Di Leo G, Sardanelli F. Statistical significance: p value, 0.05 threshold, and applications to radiomics—reasons for a conservative approach. Eur Radiol Exp. 2020;4(1):1–8.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Fonseca AL, Reddy V, Longo WE, Udelsman R, Gusberg RJ. Operative confidence of graduating surgery residents: a training challenge in a changing environment. Am J Surg. 2014;207(5):797–805.

Douglass A. The case for the 4-year residency in family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53(7):599–602.

Klebanoff JS, Marfori CQ, Vargas MV, Amdur RL, Wu CZ, Moawad GN. Ob/Gyn resident self-perceived preparedness for minimally invasive surgery. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Hodges B, Regehr G, Martin D. Difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence: novice physicians who are unskilled and unaware of it. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):S87–S9.

Finn GM, Sawdon MA. The ‘unskilled and unaware’ effect is linear in a real-world anatomy setting: Wiley Online Library; 2012.

Rahmani M. Medical trainees and the dunning–Kruger effect: when they don't know what they don't know. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):532–4.

Kämmer JE, Hautz WE. Beyond competence: towards a more holistic perspective in medical education. Med Educ. 2022;56(1):4–6.

Al Ansari M, Al Bshabshe A, Al Otair H, Layqah L, Al-Roqi A, Masuadi E, et al. Knowledge and confidence of final-year medical students regarding critical care core-concepts, a comparison between problem-based learning and a traditional curriculum. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:2382120521999669.

Henry JA, Edwards BJ, Crotty B. Why do medical graduates choose rural careers? Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(1):1–13.

Williams VM, Mansoori B, Young L, Mayr NA, Halasz LM, Dyer BA. Simulation-based learning for enhanced gynecologic brachytherapy training among radiation oncology residents. Brachytherapy. 2021;20(1):128–35.

Hunter JP, Stinson J, Campbell F, Stevens B, Wagner SJ, Simmons B, et al. A novel pain interprofessional education strategy for trainees: assessing impact on interprofessional competencies and pediatric pain knowledge. Pain Res Manag. 2015;20(1):e12–20.

Alexandraki I, Hernandez CA, Torre DM, et al. Interprofessional education in the internal medicine clerkship post-LCME standard issuance: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):871–6.

Wilkening GL, Gannon JM, Ross C, Brennan JL, Fabian TJ, Marcsisin MJ, et al. Evaluation of branched-narrative virtual patients for interprofessional education of psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(1):71–5.

Reger GM, Norr AM, Gramlich MA, Buchman JM. Virtual standardized patients for mental health education. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(9):1–7.

Levine SA, Chao SH, Brett B, Jackson AH, Burrows AB, Goldman LN, et al. Chief resident immersion training in the care of older adults: an innovative interspecialty education and leadership intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1140–5.

Senger E. Ageism in medicine a pressing problem. Can Med Assoc J. 2019;191(2):E55–6.

Hogan DB, Borrie M, Basran JF, Chung AM, Jarrett PG, Morais JA, et al. Specialist physicians in geriatrics—report of the Canadian geriatrics society physician resource work group. Can Geriatr J. 2012;15(3):68.

Flaherty E, Bartels SJ. Addressing the community-based geriatric healthcare workforce shortage by leveraging the potential of interprofessional teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S400–8.

Soulis G, Kotovskaya Y, Bahat G, Duque S, Gouiaa R, Ekdahl AW, et al. Geriatric care in European countries where geriatric medicine is still emerging. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(1):205–11.

Parmar J. Core competencies in the care of older persons for Canadian medical students. Can J Geriatr. 2009;12(2):70–3.

Flores-Sandoval C, Sibbald S, Ryan BL, Orange JB. Interprofessional team-based geriatric education and training: a review of interventions in Canada. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2021;42(2):178–95.

Hoang P, Torbiak L, Goodarzi Z, Schmaltz HN. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the geriatrics update: clinical pearls course. Can Geriatr J. 2021;24(4):304.

Masud T, Ogliari G, Lunt E, Blundell A, Gordon AL, Roller-Wirnsberger R, et al. A scoping review of the changing landscape of geriatric medicine in undergraduate medical education: curricula, topics and teaching methods. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;1-16.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Han Xian Hu for helping in data analysis, Ms. Penny Yin for helping in administration of the GSAT survey and Dr. Sharon Straus for helping in the review of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Sinai Health’s Healthy Ageing and Geriatrics Program Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kokorelias KM., interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript. Leung G.: acquisition and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. Jamshed N. and Grosse A.: preparation of manuscript. Sinha SK.: study concept, design, interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board and was conducted in accordance with all regulations. All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kokorelias, K.M., Leung, G., Jamshed, N. et al. Identifying the areas of low self-reported confidence of internal medicine residents in geriatrics: a descriptive study of findings from a structured geriatrics skills assessment survey. BMC Med Educ 22, 870 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03934-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03934-2