Abstract

Background

Despite their importance to current and future patient care, medical students’ hygiene behaviors and acquisition of practical skills have rarely been studied in previous observational study. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student’s hygiene and practical skills.

Methods

This case-control study assessed the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on hygiene behavior by contrasting the practical skills and hygiene adherence of 371 medical students post the pandemic associated lockdown in March 2020 with that of 355 medical students prior to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Students’ skills were assessed using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). Their skills were then compared based on their results in hygienic venipuncture and the total OSCE score.

Results

During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, medical students demonstrated an increased level of compliance regarding hand hygiene before (prior COVID-19: 83.7%; during COVID-19: 94.9%; p < 0.001) and after patient contact (prior COVID-19: 19.4%; during COVID-19: 57.2%; p = 0.000) as well as disinfecting the puncture site correctly (prior COVID-19: 83.4%; during COVID-19: 92.7%; p < 0.001). Prior to the pandemic, students were more proficient in practical skills, such as initial venipuncture (prior COVID-19: 47.6%; during COVID-19: 38%; p < 0.041), patient communication (prior COVID-19: 85.9%; during COVID-19: 74.1%; p < 0.001) and structuring their work process (prior COVID-19: 74.4%; during COVID-19: 67.4%; p < 0.024).

Conclusion

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic sensitized medical students’ attention and adherence to hygiene requirements, while simultaneously reducing the amount of practice opportunities, thus negatively affecting their practical skills. The latter development may have to be addressed by providing additional practice opportunities for students as soon as the pandemic situation allows.

Highlights

- The COVID-19 pandemic sensitizes medical students to hygienic aspects of venipuncture.

- The hygiene compliance of medical students is proportional to the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- During the COIVD-19 pandemic, medical students performed worse in non-hygienic tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the last century, the world population has repeatedly been confronted with pandemics primarily targeting the respiratory system, such as Influenza A, SARS, MERS-CoV as well as the current COVID-19 pandemic. As these pandemics are associated with high mortality, reducing the transmission of the virus is crucial [1].

“Social distancing” and the implementation of hygiene standards have proven to be reliable precautionary measures to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 [2]. Hence, lockdowns have been implemented all over the world [3,4,5]. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 has largely impacted and restricted public life on a global scale and made previously contact-based medical teaching of basic practical skills such as venipuncture infeasible [6, 7].

Due to the nature of their work, healthcare professionals are at a particularly high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, as well as susceptible to increased stress levels which result from a pandemic related increased workload [8, 9]. To alleviate the strain on healthcare workers, medical students have reportedly volunteered to assist them during this health care crisis [10,11,12,13]. Since proper hygiene, or lack thereof, plays a fundamental role in the transmission of pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2, medical students’ hygiene adherence is highly relevant to pandemic containment [14]. While previous pandemics have had little impact on medical students, the literature suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is now affecting medical students’ hygiene awareness, knowledge and compliance to a greater extent [8, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Nonetheless, these study results are based on surveys and not on other study models, such as observational studies. Moreover, European medical students have not been surveyed so far [15, 19, 23,24,25,26,27]. Therefore, European medical students’ adherence to hygiene protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic seems insufficiently investigated.

Methods

This unicentric case-control study examined the venipuncture skills and level of hygiene-compliance of third year medical students who participated in OSCE at the University of Cologne before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data was collected during OSCE, which is a practical test consisting of seven five-minute test stations and usually takes place in the third year of medical school in Cologne. The examined practical skills were assessed by medical students during their practical year. Failure to pass this exam was of no academic relevance to the tested students. Students are prepared for this test in a practical course, which is designed to teach skills such as hygienic venipuncture and hand disinfection. In total 910 medical students underwent OSCE from February 5th, 2019, to February 19th, 2021, in Cologne. 184 medical students participating in the OSCE in February of 2020 were excluded from this study, since they were assessed after the first SARS-CoV-2 case and before the implementation of pandemic containment measures in Germany. Therefore, the 184 medical students could not be assigned to either the control group or the lockdown group. In conclusion, only the data of 726 medical students were included in this study. Medical students who participated in OSCE prior to the first diagnosed SARS-CoV-2 case in Germany provided the control group (cohort 1). On contrary medical students who took part in OSCE after the first lockdown in March 2020 provided the investigated cohort (cohort 2). A subgroup analysis of cohort 2 allowed the comparison of medical students’ hygiene behavior at different stages of the pandemic (cohort 2a: after first lockdown; cohort 2b: after second lockdown) (Fig. 1).

All data were collected using the same standardized questionnaire (Additional file 1: Appendix 1). The focus of this study was hygienic venipuncture as part of indwelling venous cannulation or blood extraction and the total OSCE score.

Based the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov-test, all data were not normally distributed (Additional file 2: Appendix 2). Accordingly, differences between the control and the investigated group were assessed using Mann-Whitney-U test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Frequencies and percentages were demonstrated by categorical parameters, while continuous variables were expressed by their mean and standard deviation.

For all statistical analyses, IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used.

All medical students partaking in this study were of legal age. Neither the students nor the examiners knew the purpose of this study prior to the data collection. The local ethics committee reviewed and approved this research project on August 20, 2021, prior to its initiation (approval number: 21–1332). Upon enrollment in the medical program at the University of Cologne, students consented in writing to data collection and analysis. The examined retrospective data were analyzed pseudonymously.

The aim of this study was to compare medical students’ compliance with standard hygiene protocol regarding venipuncture and other hygienic tasks before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using their results in OSCE.

Results

Out of 726 medical students partaking in OSCE, 355 (48.9%) participated before (cohort 1) and 371 (51.1%) after the first lockdown in Germany during March 2020 (cohort 2). The relative score of both cohorts showed only a slight deviance regarding their relative score for OSCE (pre-lockdown: 62.53 ± 8.47; post-lockdown: 67.13 ± 7.22; p < 0.001) and venipuncture (pre-lockdown: 71.87 ± 15.85; post-lockdown: 74.36 ± 17.4; p < 0.001).

After the lockdown, 352/371 medical students (94.9%) disinfected their hands before patient contact and 212/371 (57.2%) after patient contact, whereas prior to the lockdown only 297/355 students (83.7%) did so before and 69/355 (19.4%) after patient contact (p-value for hand disinfection prior to patient contact < 0.001; p-value for hand disinfection after patient contact = 0.000).

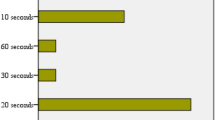

After lockdown, significantly more students disinfected their hands prior patient contact (94.95%) compared to after patient contact (57.2%) (p < 0.001). Moreover, the number of students disinfecting the puncture site increased post lockdown. (pre-lockdown: 296/355, 83.4%; post-lockdown: 344/371, 92.7%; p < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the groups regarding the observance of the 30-second exposure time of the disinfectant. Here, both demonstrated a high level of hygiene compliance (pre-lockdown: 94.9%; post-lockdown: 97.6%; p < 0.06).

There was no statistically significant difference between the two cohorts regarding the preparation of the materials (pre-lockdown: 176/355, 49.6%; post-lockdown: 201/371, 54.2%; p = 0.691), the use of sterile and unbent puncture needles (pre-lockdown: 303/355, 85.4%; post-lockdown: 311/371, 83.9%; p = 0.57) as well as discarding the puncture needle (pre-lockdown: 126/355, 35.5%; post-lockdown: 149/371, 40.2%; p = 0.177).

Notably, successful venipuncture (pre-lockdown: 169/355, 47.6%; post-lockdown: 141/371, 38%; p = 0.041), doctor-patient communication (pre-lockdown: 305/355, 85.9%; post-lockdown: 275/371, 74.1%; p < 0.001) and structure in the work processes (pre-lockdown: 264/355, 74.4%; post-lockdown: 250/371, 67.4%; p = 0.024) were less frequently demonstrated by the students partaking after the first lockdown. Thus, applying a tourniquet was the only practical skill that medical students were more proficient at after the first lockdown than before (pre-lockdown: 184/355, 51.8%; post-lockdown: 245/371, 66%; p-value < 0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Frequency of correct performance before the COVID-19 pandemic and post-lockdown in Germany, 2019–2021 (n = 726). The dotted line represents the number of medical students performing a skill correctly before the COVID-19 pandemic (Pre-SARS-CoV-2). The solid line represents the number of medical students performing a skill correctly after the first lockdown (Post-SARS-CoV-2). Frequencies are shown in percentages. Statistically significance determined by the chi-square test is marked with *. Upward arrows indicate improvement in medical students’ skills after the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, while downward arrows indicate better results prior the pandemic

Out of 371 medical students partaking in OSCE during the pandemic (cohort 2), 180 (48.5%) participated after the first lockdown in March 2020 (cohort 2a) and 191 (51.5%) after the start of the second lockdown in December 2020 (cohort 2b).

Medical students performed slightly better in OSCE after the first compared to the second lockdown (first lockdown: 68.23 ± 6.46; second lockdown: 66.1 ± 7.75; p = 0.003), while no significant statistical difference could be found between the relative score in venipuncture after the first (74.86 ± 11.3) compared to the second lockdown (73.89 ± 18.23; p = 0.833). No statistical difference was also evident in regards to hand disinfection before patient contact (first lockdown: 93.9%; second lockdown: 95.8%; p = 0.412), disinfection of the puncture site (first lockdown: 93.3%; second lockdown: 92.1%; p = 0.661), consideration of the 30 second disinfectant exposure time (first lockdown: 96.7%; second lockdown: 98.4%; p = 0.271), correct tourniquet usage (first lockdown: 67.8%; second lockdown: 64.4%; p = 0.354),the use of sterile and unbent needles (first lockdown: 84.4%; second lockdown: 83.2%; p = 0.754),discarding the puncture needle (first lockdown: 40.6%; second lockdown: 39.8%; p = 0.256). Although the cohorts did not differ significantly in their communication (first lockdown: 78.3%; second lockdown: 70.2%; p = 0.073), the number of medical students informing the patient about the procedure decreased by 8.1% during the second lockdown compared to the first.

In terms of structured work (first lockdown: 76.7%; second lockdown: 58.6%; p < 0.001) and successful venipuncture (first lockdown: 48.3%; second lockdown: 28.3%; p < 0.001), the cohort who participated in OSCE after the first lockdown in March 2020 performed better than their peers partaking during the second lockdown.

In contrast, an improvement in the disinfection of their hands after patient contact could be observed in the medical students participating after the second lockdown as compared to the first (first lockdown: 47.8%; second lockdown: 66%; p < 0.001). Materials needed for venipuncture were also more frequently adequately prepared during the second than during the first lockdown (first lockdown: 44.4%; second lockdown: 63.4%; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) classified COVID-19 as a pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 has impacted life around the world [28]. Without sufficient medication and adequate coverage rates of vaccination, preventative measures have been and still are the only way to contain the COVID-19 pandemic [29]. As part of these precautions, the WHO and the German Federal Ministry of Health recommend hygiene measures such as hand disinfection [30, 31]. To implement these measures, the campaign “AHA” (“Abstand, Hygiene, Alltagsmaske” – “Distance, Hygiene, Facemask”) was launched in Germany [31]. Other preventative measures, such as lockdowns, have been implemented all over the world [5].

Although the world’s population has been threatened by pandemics in every decade of the last 30 years, none had such a strong impact on daily life but also on the hygiene behavior of medical students. For example, during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, neither the awareness of H1N1 influenza increased nor the compliance to hygiene protocols by medical students (hand hygiene, use of mouth and nose protection) [16, 20, 21]. The hygiene behavior of medical students remained unaffected [17]. Since these studies have been based on surveys, a discrepancy between self-perception and hygiene behavior might have been possible. Nonetheless, the literature on the COVID-19 pandemic, also based primarily on self-reported questionnaires, suggests a stronger impact of SARS-CoV-2 on medical students’ hygiene knowledge, behavior and adherence [15, 18, 19, 22,23,24,25, 32, 33].

During the H1N1 influenza pandemic, the perceived individual risk of infection appeared to be a strong indicator for the level of pandemic awareness and observance of hygiene behavior among medical students [16]. Due to the more severe course of disease, increased lethality, and wider spread, medical students might perceive the risk of a SARS-CoV-2 infection as higher than they did with the H1N1 influenza [34, 35]. Pandemic containment measures, such as mandatory face masks, also increased the perceived presence of COVID-19 in everyday life [36, 37]. Moreover, the media landscape has changed since the H1N1 influenza pandemic, making information widely and easily accessible. While medical students received information about the H1N1 influenza pandemic through newspapers, medical journals or television, current medical students are more likely to obtain information about SARS-CoV-2 through social media [18, 20, 23, 32, 38, 39]. It can be assumed that social media facilitates medical students self-reported high levels of awareness and knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 as well as compliance to pandemic containment measures and hygiene standards, as indicated in several studies [15, 18, 19, 22,23,24,25, 32, 33]. The increase in hygiene compliance demonstrated in this study corresponds to the self-reported high level of knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 and the compliance regarding its containment. In contrast to these results, two questionnaire-based studies describe high levels of awareness and knowledge about SARS-CoV-2, also reported insufficient implementation of hygiene measures among medical students in Mumbai and Egypt [8, 38]. This apparent discrepancy might be explained by the different pandemic stages, during which these studies were conducted. Since the studies were conducted shortly after the pandemic was declared, the examined medical students might have been less familiar with the pandemic and its preventative measures. Furthermore, 80% of accumulated COVID-19 cases and death were reported in Europe and America at the time of this study [40]. The German medical students could have perceived the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 as higher compared to the previously studied participants in India or Egypt, driving the conflicting results. Apart from this, a multitude of other factors could potentially have influenced the outcomes of the studies. Further research is needed to confirm, whether these findings can be transferred to other American or European states. This study’s results regarding the hand hygiene compliance before and after the second lockdown further substantiate the hypothesis of a relationship between risk perception and hygiene compliance. Since more medical students properly implemented hand disinfection after the second lockdown as compared to the first, it seems plausible that a prolonged exposure to pandemic containment measures led to increased awareness, which in turn resulted in higher rates of hand disinfection after medical glove removal.

Overall, however, rates of hand disinfection after venipuncture were inadequate in all studied cohorts. This may be attributed to the utilization of noninfectious simulation manikins in this study. Hence, hand disinfection after venipuncture in this study served only a minor role in self-protection and self-cleaning, which serve as the main motivating factors for medical students’ hand disinfection after patient contact [41].

Moreover, it remains unclear if and how how the hygiene behavior of medical students exposed to COVID-19 changes after the pandemic or the course of their studies. In the literature, medical students with more experience are associated with higher awareness and compliance to SARS-CoV-2 containment measures [27, 38]. This could be due to a greater amount of medical background knowledge, simplifying the understanding of COVID-19 relevant information. Nonetheless, the literature also suggests, that the hygiene behavior of medical students without the influence of a pandemic decreases during their medical training [41,42,43,44]. Whether and how these two effects may influence each other not only during, but also after the COVID-19 pandemic needs to be investigated further.

Surprisingly, the pandemic-related improvement in hygiene compliance was not reflected in the overall venipuncture score, as medical students performed worse in terms of work structure, successful venipuncture, and patient education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The decreased doctor-patient communication could be a result of pandemic-induced psychological distress or stress due to a lack of hands-on practice opportunities since stress reportedly correlates with decreased doctor-patient communication [9, 29, 45,46,47,48,49]. Additionally, pandemic containment measures and the switch to online teaching at universities may have caused to a lack of hands-on practice opportunities for medical students [45, 50]. Consequently, medical students were unable to become sufficiently familiarized with a proper structure for practical work and to practice complex procedures, such as venipuncture. Since medical students performed even worse after the second than after the first lockdown, the accumulation of such missed practice opportunities might further affect the quality of medical students’ practical skills.

Even though the pandemic positively impacted the hygiene behavior of medical students, their impaired practical skills must be addressed to restore the former standard of practical medical education and ensure patients’ well-being.

Conclusion

This study found an overall increase in compliance with hygiene measures by medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hand disinfection after patient contact was performed more frequently during the second lockdown as opposed to the first lockdown. It can be assumed that the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures increased medical students’ awareness of hygiene. However, it remains to be seen whether the hygiene compliance of medical students will persist after the pandemic. Regardless of this, measures should be taken to reinforce this behavior and pass it on to future generations of prospective physicians.

The observed shortcomings of medical students during the pandemic in terms of structured work, doctor-patient communication, and venipuncture should be further investigated to identify possible strategies to compensate for these deficiencies going forward.

Limitations

Since this unicentric study was only conducted with medical students at the University of Cologne, a sampling bias cannot be ruled out. Thus, the results cannot be generalized to medical students from other locations.

Furthermore, this study was realized in an examination setting, so the collected data may deviate from the behavior in the clinical setting. Also, medical students’ hygiene behaviors and practical skills are a dynamic process, so a single observation time points might not capture these skills accurately.

It must also be assumed that the teachers as well as the data collectors could not escape the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sensitization of the data collectors to hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus an exaggerated assessment of medical students’ hygiene compliance by the same, thus cannot be ruled out. Another risk of a case control study could be that confounding factors might not have been identified, which in turn could have led to confounding bias.

At the same time, the retrospective nature of this study only allows conclusions about the correlation of hygiene, practical skills, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, possible causalities need to be investigated by further prospective studies.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analyzed during this study are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OSCE:

-

Objective structured clinical examinations

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

References

Abdelrahman Z, Li M, Wang X. Comparative review of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and influenza a respiratory viruses. Front Immunol. 2020;11:552909.

Khanna RC, Cicinelli MV, Gilbert SS, Honavar SG, Murthy GSV. COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and future directions. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(5):703–10.

Althwanay A, Ahsan F, Oliveri F, Goud HK, Mehkari Z, Mohammed L, et al. Medical education, pre- and post-pandemic era: a review article. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e10775.

FAZIT Communication GmbH, Auswärtiges Amt. Corona-Virus: Der Liveticker, 2021. Updated March 21, Available from: https://www.deutschland.de/de/news/coronavirus-in-deutschland-informationen.

Hamzelou J. World in lockdown. New Sci. 2020;245(3275):7.

Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese V, McKinney R. Interim guidance on medical students’ participation in direct patient contact activities: principles and guidelines. Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020;30:1–2.

Whelan A, Prescott J, Young G, Catanese V. Guidance on medical students’ clinical participation: effective immediately. Assoc Am Med Coll. 2020;17:1–2.

Modi PD, Nair G, Uppe A, Modi J, Tuppekar B, Gharpure AS, et al. COVID-19 awareness among healthcare students and professionals in Mumbai metropolitan region: a questionnaire-based survey. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7514.

Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller SG. COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers - a short current review. Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47(4):190–7.

Mihatsch L, von der Linde M, Knolle F, Luchting B, Dimitriadis K, Heyn J. Survey of German medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: attitudes toward volunteering versus compulsory service and associated factors. J Med Ethics. 2021;0:1–7.

Domaradzki J, Walkowiak D. Medical Students’ voluntary service during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Front Public Health. 2021;9(363):618608.

Rasmussen S, Sperling P, Poulsen MS, Emmersen J, Andersen S. Medical students for health-care staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):e79–80.

Soled D, Goel S, Barry D, Erfani P, Joseph N, Kochis M, et al. Medical student mobilization during a crisis: lessons from a COVID-19 medical student response team. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1384–7.

Alzyood M, Jackson D, Aveyard H, Brooke J. COVID-19 reinforces the importance of handwashing. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2760–1.

Batais MA, Temsah MH, AlGhofili H, AlRuwayshid N, Alsohime F, Almigbal TH, et al. The coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic-associated stress among medical students in middle east respiratory syndrome-CoV endemic area: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(3):e23690.

Hasan F, Khan MO, Ali M. Swine flu: knowledge, attitude, and practices survey of medical and dental students of Karachi. Cureus. 2018;10(1):e2048.

Hsu LY, Jin J, Ang BS, Kurup A, Tambyah PA. Hand hygiene and infection control survey pre- and peri-H1N1-2009 pandemic: knowledge and perceptions of final year medical students in Singapore. Singap Med J. 2011;52(7):486–90.

Hu Y, Zhang G, Li Z, Yang J, Mo L, Zhang X, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 pandemic among residents in Hubei and Henan provinces. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40(5):733–40.

Khasawneh AI, Humeidan AA, Alsulaiman JW, Bloukh S, Ramadan M, Al-Shatanawi TN, et al. Medical students and COVID-19: knowledge, attitudes, and precautionary measures. A descriptive study from Jordan. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:253.

Khowaja ZA, Soomro MI, Pirzada AK, Yoosuf MA, Kumar V. Awareness of the pandemic H1N1 influenza global outbreak 2009 among medical students in Karachi, Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5(3):151–5.

May L, Katz R, Johnston L, Sanza M, Petinaux B. Assessing physicians’ in training attitudes and behaviors during the 2009 H1N1 influenza season: a cross-sectional survey of medical students and residents in an urban academic setting. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2010;4(5):267–75.

Saddik B, Hussein A, Sharif-Askari FS, Kheder W, Temsah MH, Koutaich RA, et al. Increased levels of anxiety among medical and non-Medical University students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:2395–406.

Ali S, Alam BF, Farooqi F, Almas K, Noreen S. Dental and medical students’ knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19: a cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(S 01):S97–s104.

Noreen K, Rubab Z-e, Umar M, Rehman R, Baig M, Baig F. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices against the growing threat of COVID-19 among medical students of Pakistan. Plos One. 2020;15(12):e0243696.

Susmita S, Aneja P, Savita B, Vaidya V, Paras K. Wash and wipe to win over COVID-19. Natl J Clin Anat. 2020;9(2):48–53.

Gao Z, Ying S, Liu J, Zhang H, Li J, Ma C. A cross-sectional study: comparing the attitude and knowledge of medical and non-medical students toward 2019 novel coronavirus. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(10):1419–23.

Alsoghair M, Almazyad M, Alburaykan T, Alsultan A, Alnughaymishi A, Almazyad S, et al. Medical students and COVID-19: knowledge, preventive behaviors, and risk perception. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):842.

Ghebreyesus TA. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19: World Health Organization (WHO); 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020

Cirrincione L, Plescia F, Ledda C, Rapisarda V, Martorana D, Moldovan R, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: prevention and protection measures to be adopted at the workplace. Sustainability. 2020;12:3603.

World Health Organisation. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

Bundeszetrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, Robert Koch Institut, Die Bundesregierung Deutschland. Mit AHA durchs Jahr: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG); Available from: https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/aha/.

Olaimat AN, Aolymat I, Shahbaz HM, Holley RA. Knowledge and information sources about COVID-19 Among University students in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2020;8:254.

Taghrir MH, Borazjani R, Shiraly R. COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; a survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23(4):249–54.

Tang X, Du RH, Wang R, Cao TZ, Guan LL, Yang CQ, et al. Comparison of hospitalized patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19 and H1N1. Chest. 2020;158(1):195–205.

da Costa VG, Saivish MV, Santos DER, de Lima Silva RF, Moreli ML. Comparative epidemiology between the 2009 H1N1 influenza and COVID-19 pandemics. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):1797–804.

Matuschek C, Moll F, Fangerau H, Fischer JC, Zänker K, van Griensven M, et al. Face masks: benefits and risks during the COVID-19 crisis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25(1):32.

Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community use of face masks and COVID-19: evidence from a natural experiment of state mandates in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1419–25.

Abd El Fatah SAM, Salem M, Abdel Hakim A, El Desouky ED. Knowledge, attitude, and behavior of Egyptian medical students toward the novel Coronavirus Disease-19: a cross-sectional study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020;8(T1):443–50.

Sirekbasan S, Ilhan AO, Baydemir C. Evaluation of knowledge, attitudes and practices of health services vocational schools’ students with regard to COVID-19. Gac Med Mex. 2021;157(1):70–5.

World Health Organisation. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 23 March 2021 2020 Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19-23-march-2021.

Meyer A, Schreiber J, Brinkmann J, Klatt AR, Stosch C, Streichert T. Deterioration in hygiene behavior among fifth-year medical students during the placement of intravenous catheters: a prospective cohort comparison of practical skills. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):434.

Wu EH, Elnicki DM, Alper EJ, Bost JE, Corbett EC Jr, Fagan MJ, et al. Procedural and interpretive skills of medical students: experiences and attitudes of third-year students. Acad Med. 2006;81(10):48–51.

Wu EH, Elnicki DM, Alper EJ, Bost JE, Corbett EC Jr, Fagan MJ, et al. Procedural and interpretive skills of medical students: experiences and attitudes of fourth-year students. Acad Med. 2008;83(10):63–7.

Woelfel IA, Takabe K. Successful intravenous catheterization by medical students. J Surg Res. 2016;204(2):351–60.

Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2.

Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A, Anfinrud P. The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(22):11875.

Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996–1009.

Erasmus V, Daha TJ, Brug H, Richardus JH, Behrendt MD, Vos MC, et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(3):283–94.

Byrne L, Gavin B, Adamis D, Lim YX, McNicholas F. Levels of stress in medical students due to COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:383–8.

Friederichs H, Brouwer B, Marschall B, Weissenstein A. Mastery learning improves students skills in inserting intravenous access: a pre-post-study. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(4):Doc56.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy Meyer, Hannah Ziegelski, Dorothee Meyer, Janik Riese, Konstantin Marbach and Reka Fuchs for proofreading this article.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was financed by the Department of clinical chemistry, University of Cologne, faculty of medicine and university hospital, Cologne, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study design was created by AM. CS ensured the data acquisition. AM analyzed and interpreted the data as well as drafted the research article. TS, AK and CS substantially revised this article. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to its initiation, this study was evaluated and approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Cologne on August 20, 2021 (approval number: 21–1332). All methods were performed according to the guidelines of this ethics committee as well as the Declaration of Helsinki. The retrospective personal data were accessed only by authorized personnel. The need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Cologne, because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Rating of the 11-item questionnaire.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Test of normal distribution prior and after the first COVID-19 lockdown.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3.

Test of normal distribution for the different student cohorts.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Meyer, A., Stosch, C., Klatt, A.R. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on medical students’ practical skills and hygiene behavior regarding venipuncture: a case control study. BMC Med Educ 22, 558 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03601-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03601-6