Abstract

Background

Indonesia has applied a national competency exit-examination for medical graduates since 2014, called The Indonesia Medical Doctor National Competency Examination (IMDNCE). This examination is administered to ensure the competence of medical graduates from at present 83 medical schools in Indonesia. Although many studies reported their evaluation on medical licensing examinations, there are not many studies performed to evaluate the correlation of a national licensing examination to the graduates’ clinical practice.

Aims

This research aimed to evaluate the performance of new medical doctors in Indonesia in their internship period after the IMDNCE completion, and whether it might become a predictive indicator for the new medical doctors’ clinical performance.

Methods

An observational cross-sectional study was performed in November–December 2017 on 209 doctors who were new medical graduates. Thirty-one senior doctors from a range of regions in Indonesia who were recruited and trained previously participated in the observation. The Clinical Performance Instrument (CPI) tool was developed as an evaluation tool of the new doctors’ clinical competence to be observed for three weeks. The obtained data were analysed using descriptive statistics and correlated to the IMDNCE scores.

Results

The mean (95% CI) of the CPI for all participants was 83.0 (80.8–85.2), with no correlation of CPI score with IMDNCE results in domains of communication, professionalism and patient safety (p > 0.05). However, the mean total of the CPI observation scores from doctors who graduated from public medical schools was higher than those graduating from private medical schools. Also, there were differences in scores related to the institution’s accreditation grade (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

There is no difference between CPI and national competency examination results. There was no statistical correlation between the clinical performance of new medical doctors during their internship to CBT and OSCE scores in the national competency examination. New doctors’ performance during internship is affected by more complex factors, not only their level of competencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

National medical competency examinations have been conducted in many countries to guarantee that the graduating medical doctors are competent based on the required standard. These tests of doctors’ abilities are adminstered to ensure the quality of health-care. Assuring patient safety is one of the main considerations of performing national competency examination [1]. A study in the US indicated that the increased achievement on the national medical examination was correlated with the decrease of patient mortality rate [2]. Hence, developing a standardized national competency examination is very important, especially in countries such as Indonesia that have high mortality rates.

National medical competency examinations have been widely utilised as an evaluation tool in medical education [3,4,5]. The examination can assess communication, professionalism, patient safety, clinical management, and many other medical skills. National examinations can be used to measure knowledge, skills and attitude of clinical professionalism comprehensively [6], to assess professional development [5], to predict medical doctors’ future clinical performance [7], and also to predict their performance on the subsequent medical training [3, 8]. Norcini et al. [2] also reported that there was a performance difference between doctors who participated in a national licensing examination and those who did not participate.

National medical competency examination in Indonesia

The Indonesia Medical Doctor National Competency Examination (IMDNCE) is a national medical competency exit exam which has been established since 2014 based on Indonesian Medical Education Act No. 20/2013, which consists of two components. There is the multiple-choice questions using computer-based testing methods (MCQs-CBT) to assess candidates’ knowledge, and an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) to assess candidates’ clinical skills performance. The IMDNCE is an important tool, not only to evaluate students’ achievement towards the national standard, but also to evaluate medical graduates’ knowledge/skills, accountability and development [9].

Medical internship programme in Indonesia

Newly graduated doctors in Indonesia are required to undergo the one-year internship programme. This compulsory programme serves as the first medical practice of the new doctors. During the one-year programme, each new doctor is assigned in a district hospital of the primary health-care facility under the supervision of a senior doctor. New doctors are allowed to conduct independent medical practice after completing the one-year internship programme.

Rationale

Many studies reported their evaluation of national licensing examinations [3, 4, 8, 10]. However, studies about the effect of a national licensing examination to the subsequent medical practice are scarce. This study aimed to evaluate the performance of new medical doctors in Indonesia in their internship period after the IMDNCE completion. In addition, this study also investigated whether the IMDNCE performance might become a predictive indicator for the new medical doctors’ clinical performance.

Methods

Study design and setting

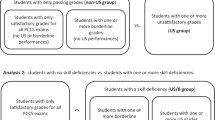

This observational research was a cross-sectional study conducted from November to December 2017 in a range of regions in Indonesia. The details of the study’s protocol are portrayed in Fig. 1.

Participants

A total of 209 newly graduated doctors who joined the internship program between February 2017 – February 2018 participated in this study. Medical schools in Indonesia are grouped into regions. Hence, purposive sampling was applied to ensure representativeness of each region, schools’ nature (i.e., public or private), and accreditation levels of medical schools (i.e., highest A, B or the lowest C) where the new doctors graduated (see Fig. 1).

In addition, 31 senior doctors from a range of regions in Indonesia were recruited as observers. The observers were trained how to observe the new doctors’ clinical performance using a validated instrument. The observation was conducted for a three-weeks period. The observers were requested to conduct clinical performance evaluation at least once-a-week for each of the new doctors to obtain three observation reports throughout the observation period. The observation was conducted in a range of clinical settings, such as outpatient clinic, emergency room, in-patient setting and field visit service. The observers were provided with information about the general purpose of the study, but were blinded to the characteristics of the interns to avoid possible biases.

Instrument

This study applied the Clinical Performance Instrument (CPI) which was based on the IMDNCE OSCE examination rubric. There are seven domains in the examination, which are anamnesis, physical examination, supportive examination, clinical diagnosis and differential diagnosis, patient management (pharmacology and non-pharmacology), health education, and professionalism. Discussion with an expert panel was conducted during CPI development to conclude the three domains of CPI. The CPI then underwent a validity study towards 58 medical doctors who practice in primary care setting. Using Likert scale for each items, the medical doctors completed in the instrument based on their perception and experience during clinical practices. The instrument showed a good reliability score (Cronbach-alpha = 0.93) [11].

The CPI consists of three domains of competence (i.e., doctor-patient communication/K1, professionalism/K2 and patient safety/K3) which incorporates 25 observation items (see Table 1), in a 4-point scale. Technical skills (i.e., physical examination, procedural skills, clinical reasoning and written communication) fall under patient safety (K3) domain.

Data analysis

The obtained data were analysed using descriptive statistics to measure mean, median and standard deviations of the three-weeks observations scores. The CPI scores were analysed based on the medical schools’ status and accreditation using the Mann–Whitney and Kruskall-Wallis tests.

The CPI observation scores were subsequently tested using correlation and multiple linear regression analyses against the IMDNCE scores (computer-based test/CBT and OSCE), to measure the predictive value. Multiple linear regression was capable of measuring the relationship between two independent variables, for this instance the IMDNCE score as predictor of CPI (significant if p value < 0.05).

Ethical considerations

This study was ethically approved by the Committee of Research Ethics, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Sebelas Maret (No: 1066/XII/HREC/2016). All study participants (i.e., new doctors and observers) had given their consent before the observer training and the three-weeks observation.

Results

Demographics

The 209 new doctors were graduated from medical schools with different levels of accreditation (A, B and C), institutional status (private and public) and region of origin. The new doctors were also conducting their internship in a range of regions (Table 2).

CPI observation scores

The mean (95% CI) of the CPI for all participants was 83.0 (80.8–85.2). The mean score for each domains of CPI, there were communication 80.5 (77.2–83.7), profesionalism 93.9 (92.4–95.4), and patient safety 77.8 (74.4–81.1). The mean (95% CI) total of the CPI observation scores of new doctors graduated from public medical schools were better than those graduated from private medical schools, 85.3 (82.6–88.1) vs 80.3 (76.8–83.1) with p = 0.044. Moreover, new doctors graduated from A-accredited medical schools performed better than those graduated from B and C-accredited medical schools with mean (95% CI) total CPI score A vs B vs. C: 86.0 (83.3–88.7) vs 79.2 (75.2–83.2) vs 78.8 (70.2–87.5), p = 0.002. The results of CPI observation scores are summarised in Table 3.

Furthermore, the CPI observation scores were tested against the IMDNCE CBT and OSCE scores of the corresponding domains (i.e., namely communication, professionalism and patient safety). There were no correlations between the CPI observation scores to IMDNCE CBT nor OSCE scores (p = 0.368 – 0.928) as outlined in Table 4.

Discussion

IMDNCE serves as a means of standardization as well as quality assurance of medical school graduates in Indonesia. As a standardized exit examination, IMDNCE is expected to be able to predict the performance of fresh graduate doctors in their early phase of clinical practice, especially during the internship [1, 12, 13]. Standardization of graduates through IMDNCE has also been expected to assure the quality of Indonesian doctors. This expectation is manifested in the study result, showing that there was no difference between CBT and OSCE scores and clinical observation results during internship (p > 0.05). There were no differences in their performances regarding communication, professionalism, and patient safety competences as well. These results may suggest that through IMDNCE, doctors could demonstrate standardized quality medical care and the test items (CBT and OSCE) could be used as tools to standardize the quality of clinical performance.

National examinations are necessary to assure the quality of doctor candidates within the diversity of medical education institutions [14]. The diversity is influenced by several factors ranging from the input, process, and output of the curriculum. The Indonesian Doctors Standard of Competencies (SKDI) 2012 acts as a national standard for the medical education process with seven areas of competences. However, the implementation of the standard is still influenced by other factors that might affect the quality of medical education in Indonesia, e.g. human resource, learning resources, research development and organization, curriculum development and innovation, and a comprehensive internal quality assurance process. These factors emphasize the need for output standardization through IMDNCE.

Institutional factors are not the only concerns that contribute to the quality of output and the clinical performance of medical school graduates. Internship as the initial phase of clinical practice in real settings for Indonesian medical school graduates might be affected by several factors that are not taught during their educational period [15, 16]. The national health care system with its universal health coverage principal becomes a major influence for clinical performance [1]. The Indonesian health care system prioritizes the strengthening of primary services, whether promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative, in which the intern doctors are at the forefront of primary care. So the phenomenon raises the ratio of patient/doctor by increasing the number of doctors in primary care facilities [17], which, of course, leads to a shift in the quality of care that is affected by the number of patients and the length of service time. This would be different if the phase of education, both pre-clinic and clinics are more ideal both theoretical and clinical practice. Although the professional performance of physicians in this study is not influenced by CBT and OSCE value output, it is necessary to review the efficiency of physician work in terms of implementation of the national health care system, especially in the primary care.

This study identified that the IMDNCE results did not predict new-doctors’ clinical performance scores. The results might be related to the interns’ practice that not yet representing the competences in the Indonesian Doctors Standard of Competences (SKDI) since the IMDNCE items are developed based on SKDI. The new-doctors would not be able to practice in the optimum medical authority stated in SKDI since they were still under the supervision of senior doctors. Moreover, the real clinical setting might differ with what the new-doctors had learnt during their education. For instance, some of the new-doctors were assigned in a district hospital while some of them were in the primary health care centre which had several possible limitations such as funding, facility and the lower doctor-to-patient ratio. The new-doctors might use distinct approaches to cope with the diverse environments [18], which could be different to their approach examined during IMDNCE. Moreover, clinical competence judgement may show a different result when performed under unsimilar administration condition [19]. The disparity between the standards used in IMDNCE and the actual clinical setting makes it complicated to predict the clinical performance based on the IMDNCE results. The level of knowledge and skills are traditionally pertinent to the doctors’ preparedness for practice. However, several factors are argued to influence the performance of doctors in the clinical setting. Doctors shape their conception of professionalism and clinical empathy through the complex cognitive process of role modelling [20]. Meanwhile, mentorship quality in the workplace is argued to influence doctors’ confidence and perception about their own competencies [21]. The individual factors of the novice practitioners during the transitional period, such as the ability to adjust, adapt and manage stress, predispose their clinical performance [22].

Nevertheless, the new-doctors’ clinical performance observed was significantly different for each of the medical schools’ accreditation level. The new-doctors graduated from ‘A’-level accredited medical schools achieved better CPI score than the other levels. This finding corresponds with the evaluation results in 2014–2016 in which IMDNCE participants from higher-accredited medical schools achieved the better score than others from lower-accredited medical schools [23, 24]. Moreover, this result also resonates to another study in USMLE context in which candidates who trained in accredited educational institutions achieved better examination performance where accreditation of educational programmes was associated with the production of more highly skilled physicians [25]. Therefore, this study is capable of providing an evaluation of the educational outcomes at the higher, Level 4A, of the Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy [26] based on graduates’ actual practice observed.

Limitations

This study showed different results compared to other studies which suggested that national/licensing examination performance predicted performance in the actual clinical practice. Nonetheless, this study included a range of clinical performance aspects such as communication, professionalism and patient-safety for newly-graduated doctors when published studies only focused on single clinical performance [27, 28], or performed after many years of practice [7, 29]. Hence, this study provides new information about short-term performance evaluation following a national competency examination. The instrument used could further validated to ensure construct and concurrent validity, to be used in other settings. Additionally, this study was observational where it might be hard to control the possible confounding factors such as the variety of geographical area in Indonesia. Nevertheless, this study investigated participants from a range of provinces in Indonesia to represent both urban and rural areas which might mitigate the possibility of geographical confoundings. Since cause-effect relationships are difficult to establish even in an experimental research, a more rigorous methodology such as quasi-experiments with control groups would provide wider perspectives.

Conclusion

There is no difference between CPI and national competency examination results, but there was a significant difference of clinical performace score based on graduates’ medical schools’ nature and accreditation level. There was no statistical correlation between clinical performance of new medical doctors during internship to CBT and OSCE scores in national competency examination. This may suggest that new doctors’ performance during internship is affected by more complex factors, not only their level of competencies. Further cohort studies with longer observation period are recommended to investigate the development of medical graduates’ clinical practice as a follow up to this research.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data of this study is available upon request to the researchers/authors.

Abbreviations

- IMDNCE:

-

Indonesia Medical Doctor National Competency Examination

- SKDI:

-

Standar Kompetensi Dokter Indonesia—The Indonesian Doctors Standard of Competencies

- OSCE:

-

Objective Structured Clinical Examination

- CPI:

-

Clinical Performance Instrument

References

Archer J, Lynn N, Roberts M, Gale T, de Bere SR. The medical licensing examination debate. Regul & Governance. 2017;11:315–22.

Norcini JJ, Boulet JR, Opalek A, Dauphinee D. The relationship between licensing examination performance and the outcomes of care by international medical school graduates. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1157–62.

Dillon GF, Swanson DB, McClintock JC, Gravlee GP. The relationship between the american board of anesthesiology part 1 certification examination and the United States medical licensing examination. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):276–83.

Melnick DE. Licensing examinations in North America: is external audit valuable? Med Teach. 2009;31(3):212–4.

Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, Holmboe ES, Lipner RS. Performance during internal medicine residency training and subsequent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(11):869–76.

Ahn DS, Ahn S. Considering the cut score of Korean National Medical Licensing Examination. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2007;4:1.

Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, Wenghofer E, Jacques A, Klass D, Smee S, Blackmore D, WInslade N, Girard N, et al. Physician scores on a national clinical skills examination as predictors of complaints to medical regulatory authorities. JAMA. 2007;298(9):993–1001.

Hiller K, Franzen D, Heitz C, Emery M, Poznanski S. Correlation of the national board of medical examiners emergency medicine advanced clinical examination given in july to intern American board of emergency medicine in-training examination scores: a predictor of performance? West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(6):957–60.

Goldie J. AMEE Education Guide no. 29: evaluating educational programmes. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):210–24.

Rahayu GR, Suhoyo Y, Nurhidayah R, Hasdianda MA, Dewi SP, Chaniago Y, Wikaningrum R, Hariyanto T, Wonodirekso S, Achmad T. Large-scale multi-site OSCEs for national competency examination of medical doctors in Indonesia. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):801–7.

Ranti A. Hubungan Lingkungan Pembelajaran Klinis dengan Persepsi Tentang Performa Dokter Internsip Lulusan Fakultas Kedokteran UNS. Surakarta: Universitas Sebelas Maret; 2018.

Han ER, Chung EK. Does medical students’ clinical performance affect their actual performance during medical internship? Singapore Med J. 2016;57(2):87–91.

Kim PY, Wallace DA, Allbritton DW, Altose MD. Predictors of success on the written anesthesiology board certification examination. Int J Med Educ. 2012;3:225–35.

West C, Kurz T, Smith S, Graham L. Are study strategies related to medical licensing exam performance? Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:199–204.

Carr SE, Celenza A, Puddey IB, Lake F. Relationships between academic performance of medical students and their workplace performance as junior doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:157.

Norman G, Neville A, Blake JM, Mueller B. Assessment steers learning down the right road: impact of progress testing on licensing examination performance. Med Teach. 2010;32(6):496–9.

Ministry of Health of The Republic of Indonesia. Indonesia Health Profile 2015. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of The Republic of Indonesia; 2016.

Schiller JH, Stansfield RB, Belmonte DC, Purkiss JA, Reddy RM, House JB, Santen SA. Medical students’ use of different coping strategies and relationship with academic performance in preclinical and clinical years. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(1):15–21.

Roberts WL, Boulet J, Sandella J. Comparison study of judged clinical skills competence from standard setting ratings generated under different administration conditions. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(5):1279–92.

Ahmadian Yazdi N, Bigdeli S, Soltani Arabshahi SK, Ghaffarifar S. The influence of role-modeling on clinical empathy of medical interns: a qualitative study. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2019;7(1):35–41.

LaDonna KA, Ginsburg S, Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):763–8.

Alexander C, Millar J, Szmidt N, Hanlon K, Cleland J. Can new doctors be prepared for practice? A review Clin Teach. 2014;11(3):188–92.

PNUKMPPD. Umpan balik bagi institusi peseta UKMPPD Agustus 2014-Mei 2015, vol.1. Jakarta: Panitia National Uji Kompetensi Mahasiswa Program Profesi Dokter; 2015.

PNUKMPPD. Umpan balik bagi institusi peseta UKMPPD Februari 2016-November 2016, vol.2. Jakarta: Panitia National Uji Kompetensi Mahasiswa Program Profesi Dokter; 2017.

van Zanten M, Boulet JR. The association between medical education accreditation and examination performance of internationally educated physicians seeking certification in the United States. Qual High Educ. 2013;19(3):283–99.

Morrison J. Evaluation. In: ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. edn. Edited By Cantillon P, Wood D. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010.

Lee Y-M, Kim BS. association between student performance in a medical communication skills course and patient-physician interaction scores on a clinical performance examination. Korean J Med Educ. 2008;20(4):313–20.

Ram P, van der Vleuten C, Rethans JJ, Schouten B, Hobma S, Grol R. Assessment in general practice: the predictive value of written-knowledge tests and a multiple-station examination for actual medical performance in daily practice. Med Educ. 1999;33:197–203.

Wenghofer E, Klass D, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, Jacques A, Smee S, Blackmore D, Winslade N, Reidel K, Bartman I, et al. Doctor scores on national qualifying examinations predict quality of care in future practice. Med Educ. 2009;43(12):1166–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors highly appreciate the participation and support of medical interns and supervisors in the study.

Funding

This research is funded by the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of The Republic of Indonesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were significantly contributing to the manuscript writing, completion, revision and also during research phase. PSU was involved in writing most parts of this manuscript, designing the research project, designing the CPI, training the supervisors, collecting the data and analysing the data. ABT was involved in writing most parts of this manuscript, designing the research project, designing the CPI, training the supervisors, collecting the data and analysing the data. RR was involved in writing some parts of this manuscript, training the supervisors, and collecting the data. FK was involved in writing some parts of this manuscript, training the supervisors, and collecting the data IA was involved in writing some parts of this manuscript, training the supervisors, and collecting the data CA was involved in writing some parts of this manuscript, training the supervisors, and collecting the data. GRR was involved in writing some parts of this manuscript, designing the research project and analysing the data. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

Prattama Santoso Utomo, MD, MHPEd (PSU) is an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Education and Bioethics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta – Indonesia. His research interests are teaching–learning, curriculum development and peer-assisted learning in medical education.

Amandha Boy Timor Randita, MD, MMedEd (ABT) is a medical education lecturer in Faculty of Medicine Universitas Sebelas Maret (FM-UNS). He graduated as Medical Doctor from FMUNS in 2012 and completed her Master degree in medical education from Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada in Indonesia in 2016. His interests are curriculum development, faculty development, and research.

Rilani Riskiyana, BSN, MMedEd (RR) is an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Education and Bioethics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta – Indonesia.

Felicia Kurniawan, DR, MD, M.Kes (FK) is an associate professor in the Public Health Department, School of Medicine Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia. Her interest covers research in non communicable disease and medical education.

Irwin Aras, MD, M.Epid, MMedEd (IA) is the Head of Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine Hasanuddin University of Indonesia. His research preference covers student assessment, interprofessional education, and quality assurance.

Cholis Abrori, MD, M.Kes, M.Pd.Ked (CA) is the Head of Medical Education Unit, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Jember, Indonesia. His research interest mainly focus on student assessment.

Gandes Retno Rahayu, MD, MMedEd, PhD (GRR) is a professor in the Department of Medical Education and Bioethics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta – Indonesia. Her research interest is in assessment, teaching–learning and interprofessional education in HPE.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the experiment protocol for involving humans was in accordance to guidelines of national/international/institutional or Declaration of Helsinki, and this study was granted an ethical approval by the Committee of Research Ethics, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Sebelas Maret (No: 1066/XII/HREC/2016). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, including new doctors and observers, before participating in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests related to this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Utomo, P.S., Randita, A.B.T., Riskiyana, R. et al. Predicting medical graduates’ clinical performance using national competency examination results in Indonesia. BMC Med Educ 22, 254 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03321-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03321-x