Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has greatly affected medical education in addition to clinical systems. Residency training has probably been the most affected aspect of medical education during the pandemic, and research on this topic is crucial for educators and clinical teachers. The aim of this study was to understand the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic comprehensively through a systematic review and analysis of related published articles.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted based on a predesigned protocol. We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE databases until November 30, 2020, for eligible articles. Two independent reviewers extracted data by using a customized form to record crucial information, and any conflicts between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with another independent reviewer. The aggregated data were summarized and analyzed.

Results

In total, 53 original articles that investigated the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training were included. Studies from various regions were included in the research, with the largest percentage from the United States (n = 25, 47.2%). Most of these original articles were questionnaire-based studies (n = 44, 83%), and the research target groups included residents (79.55%), program directors (13.64%), or both (6.82%). The majority of the articles (n = 37, 84.0%) were published in countries severely affected by the pandemic. Surgery (n = 36, 67.92%) was the most commonly studied field.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly affected residency training globally, particularly surgical and interventional medical fields. Decreased clinical experience, reduced case volume, and disrupted education activities are major concerns. Further studies should be conducted with a focus on the learning outcomes of residency training during the pandemic and the effectiveness of assisted teaching methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has greatly affected every facet of the health care system since COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The pandemic overwhelmed health care systems rapidly in many countries, and numerous studies have investigated the clinical effects of the pandemic [1,2,3,4,5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has not only damaged clinical systems but also affected medical education severely. However, research on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on education is as-yet limited.

When considering medical education, residency training has probably been the most affected during the COVID-19 pandemic because the core of residency training is clinical experience and clinical skill proficiency, which have been reduced because of multiple factors in the pandemic. Dedeilia et al. published a systematic review on educational challenges in the COVID-19 era and revealed that both medical and surgical education have been severely affected [6]. However, the article was published in the early stage of the pandemic when literature on the topic was limited, and the focus of the research was not only residency training but also medical students’ education. Additionally, most of the included articles were nonoriginal manuscripts and may have been insufficient to analyze the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training.

Understanding the influence of the pandemic on residency training is crucial to being able to adopt methods to maintain consistency in training quality. The aim of this study was to identify the real effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training through a systematic review of relevant published articles and further analysis of the results. Our study may help residency training program directors worldwide to comprehensively understand the influence of the pandemic and adopt assisted teaching methods to provide effective training.

Methods

Systematic review protocol

A systematic review was conducted based on a predesigned protocol in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [7].

Search strategy

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for eligible articles until November 30, 2020 (for approximately 1 year from the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic). The search strategy was based on the following algorithm: (“COVID- 19” [All Fields] OR “COVID-2019” [All Fields] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” [Supplementary Concept] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” [All Fields] OR “2019-nCoV” [All Fields] OR “SARS-CoV-2” [All Fields] OR “2019nCoV” [All Fields] OR (“Wuhan” [All Fields] AND (“coronavirus” [MeSH Terms] OR “coronavirus” [All Fields]))) AND (“education, medical” [MeSH Terms] OR (“education” [All Fields] AND “medical” [All Fields]) OR “medical education” [All Fields] OR “residency training” [All Fields] OR “trainee” [All Fields]).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We aimed to include all original articles discussing the effect of COVID-19 on residency training in different specialties. Furthermore, we only included studies that were published in English. We excluded nonoriginal articles, such as reviews, editorials, perspectives, short or special communications, and letters to editors. Studies regarding medical students or paramedical specialties, such as dentistry or nursing, were excluded. Moreover, studies focused on methodologies or technological innovations rather than residency training were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

Figure 1 depicts the study selection and review processes. After selecting articles from two databases, we removed duplicate articles manually. Two independent reviewers (SKH and HYL) scanned the title and abstract of all articles to determine relevancy in light of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Articles without abstracts were included for full-text assessment and evaluated at that stage. Two reviewers shared their results after scanning the title and abstract of all articles, and only articles that were excluded by both reviewers were eliminated from further full-text assessment. During the full-text assessment stage, we used a customized Excel sheet to record essential information of the article. Article type, first author of the article, training specialties, publication date, target group, and country of the enrolled population were extracted. We classified training specialties into four categories. Surgical field including otorhinolaryngology, orthopedics, general surgery, neurosurgery, obstetrics and gynecology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, urology, ophthalmology and oculoplastic surgery. Medical filed including internal medicine, diagnostic radiology, pediatrics, emergency medicine and pathology. Interventional field including interventional cardiology, interventional radiology and endoscopy.

Then, two reviewers evaluated the extracted full-text articles separately according to the criteria. Any conflicts between the two reviewers regarding the extracted articles were resolved through discussion with another reviewer (SYC). The included articles were further quantitatively analyzed or described narratively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of aggregated data are presented using count and proportions. Descriptive analysis was performed according to publication date, country, and specialty separately. Further subanalysis was performed based on study content, geographic location, pandemic severity, and specialty category. Pandemic severity was defined according to the World Health Organization dashboard [8]. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (2016, Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, Washington).

Results

The search yielded 3581 and 2567 articles from MEDLINE and EMBASE, respectively. After removing duplicates, 4583 articles were left; their titles and abstracts were scanned, and 312 relevant articles were identified. The full texts of these 312 articles were reviewed with 179 articles included. Among the included articles, 53 original articles were undergone further data extraction and quantitative analyses. The key information of the 53 original articles is summarized in Table 1 and Additional file 1, with the articles presented in alphabetical order by name of first author.

Quantitative analyses of original articles

Of the 53 original articles, 8, 11, 12, 7, 6, and 3 articles were published in May, June, July, August, September and October, and November 2020, respectively (Fig. 2). The geographic distribution of the research target group of the articles is presented in Fig. 3. By country, the most studies were performed in the United States (25 articles), followed by Italy and the United Kingdom (4 articles). Most studies focused on residency training in a single country, and only nine articles involved residents of multiple countries as the target group.

Subgroup analyses of original articles

Most of these original articles were questionnaire-based studies (n = 44, 83%). Among questionnaire-based studies, 35 (79.6%) involved residents directly, 6 (13.6%) involved program directors, and 3 (6.8%) involved both groups. The distribution of published articles according to the degree of the COVID-19 pandemic was demonstrated as following: 37 (84.0%), 2 (4.6%), and 3 (6.8%) articles were published in countries with > 1,000,000, 500,001–1,000,000, and 50,001–100,000 cases, respectively. Table 2 presents studies according to specialty. Most articles focused on surgery (n = 36, 67.92%) and interventional skill training in different specialties (n = 9, 16.98%).

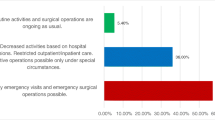

Possible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training

We summarize the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic of residency training mentioned in these articles in Table 3. The most common effect of the pandemic on residency training was decreased clinical experience and failure to meet the training requirements of the specialty. Change in the working hours of residents varied based on hospital and specialty. Some articles reported decreased working hours because of reduced patient volume and elective operations. However, some residents may have experienced increased burdens because of extra work due to the pandemic. Educational activities such as lectures or case discussions may have increased or decreased depending on the situation. Furthermore, some articles mentioned redeployment to other tasks to manage the COVID-19 pandemic and some COVID-19-related problems, such as inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and quarantine policies. Moreover, residents had worse mental health and increased anxiety regarding their board exams and career.

Discussion

Our study is the first to systematically review and analyze published academic articles focusing on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training after 1 year of the pandemic. We provided statistical information on the publication timeline, geographic distribution, publication types, and study specialties. In addition, we summarized the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training narratively.

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. With respect to the global accumulation of cases, the number of confirmed patients with COVID-19 exceeded 1 million on April 2, and the number of deaths due to COVID-19 exceeded 100,000 on April 10 [62]. The first original article on residency training during the pandemic was published on May 16, and publication on this topic peaked in July with 12 articles [57]. This timeline reflects rapid intensification of the global pandemic in this period, which affected residency training in many specialties. Additionally, several developed countries, such as the United States, Italy, and the United Kingdom, had a rapidly increasing number of COVID-19 cases at this time, which may have been the reason for the increasing number of studies on this topic in these countries, given their focus on research and medical education. Although number of affected cases in countries apart from Americas and Europe is high, the publications carried out from these regions are disproportionately low. It may relate to research energy of individual country, publication bias or selection bias from our inclusion language criteria. Owing to lack of adequate publications, we cannot make a comprehensive between-country comparison of the impact on residency training and further investigation is warranted in the future.

Regarding geographic distribution, the studies were globally distributed, having been conducted in both developed or developing countries, and several multinational studies were also noted. Although the United States was responsible for almost half the articles reviewed, the results suggested that residency training programs were being affected globally by the COVID-19 pandemic. The effect of the pandemic on residency training should be identified by residency training program directors, and rolling adjustments and training program revisions are necessary to provide adequate training and maintain consistent quality during the pandemic.

The majority of the studies were published in countries severely affected by the pandemic, and therefore, medical education and residency training were substantially affected in these countries. Fewer elective operations because of policies established during the pandemic were noted in some specialties, such as urology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and diagnostic angiography [12, 63,64,65]. The policies of lockdown and quarantine reduced patient volume for some diseases, such as trauma and infectious diseases, which induced less clinical exposure [66, 67]. Redeployment and reassignment of residents occurred for pandemic-related work [41]. All these factors contributed to possible inadequate training and failure to meet the requirements of training programs.

Surgical specialties were the most and first affected. Elective surgeries were cancelled or postponed during the pandemic, providing less practice and experience for the residents [63,64,65, 67]. Additionally, residents in surgical specialties were redeployed to manage patients with COVID-19 or perform other work due to medical resource reallocation, disrupting their original surgical training courses. Another disruption was the “stay at home” policy, which resulted in fewer trauma cases and related surgeries [68]. All these factors affected surgical resident training. A similar situation occurred in interventional medical fields, such as radiology, cardiology, and gastroenterology [12, 69, 70]. Hands-on practice and on-the-job skill development in residency training were affected during the pandemic.

Although the effect of COVID-19 on the internal medicine field was rarely mentioned in the articles, the influence still existed. Residents focused on treating patients with COVID-19, which decreased their clinical experience with other diseases [15]. The fear of becoming infected with COVID-19 in hospitals reduced patient volume, except for patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19 [71]. Moreover, the policy of wearing a mask decreased the incidence of infectious diseases such as influenza [72]. These conditions occurred in many countries, even in those less severely affected by the pandemic. Lo et al. published an observational study on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency medicine residency training in a teaching hospital in Taiwan [31]. As of this writing, in Taiwan, the number of patients with confirmed COVID-19 has remained under 1000, no large-scale lockdown has been implemented, and the health care system is robust. However, significant decreases were nevertheless noted in case volume and residents’ clinical exposure in Taiwan. Yet, the real effect of decreased clinical exposure is unknown because no study has assessed the learning outcomes of residents undergoing training during the pandemic. Other than negative impact, studies also revealed some positive impact worth mentioning and included implementation of new technology educational tools, higher quality of live-streamed didactic lectures, broader applications of telemedicine, increased time on research activities and self-study. A study collected narrative impressions revealed some surgical residents considered the pandemic is a valuable chance to learn deeper on communicable diseases and to think of the entire body again rather than separate body organs.

The mental health and quality of life of residents have potentially been affected. The psychological pressure has been heavy when managing patients with COVID-19 because of infection risk and inadequate PPE in some hospitals. Quarantining due to caring for patients with confirmed COVID-19 and the fear of infecting family led residents to live alone with little family support [14]. Excessive working hours and burnout have been common, although these factors have varied by individual. These factors can induce a stressed and unhealthy mental state and impair learning [30].

According to our results, most of the original studies used questionnaire surveys. In the early stage of the pandemic, the advantage of this research type was that it was quick, saved time, and was easily accessible [73]. The results of these questionnaire surveys with either residents or program directors as respondents exhibited high consistency and reflected the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residents. However, these questionnaire studies had some limitations, such as subjective questions, voluntary response bias, and heterogeneity of respondents and institutional bias, which may limit their generalizability [74]. Only nine studies had conducted objective investigations and had “real numbers” comparing the prepandemic and pandemic periods [17, 31, 36, 39, 45, 49, 50, 54, 61]. These studies indicated the severity of the effect and identified domains that were affected. Further research of this type is warranted to comprehensively understand the influence of the pandemic. Although both residents and program directors have a high consistency on clinical training, educational modifications and workforce restructuring issue, there are still some discrepancies. In a study discussing the impact on interventional cardiology, majority of residents believed that the pandemic affected their procedural competency but nearly all of the respond program directors believed that their residents would be ready for independent practice after completing the training year [56]. Another study collected narrative responses the program directors also revealed a more positive impressions on impact of COVID-19 on residency training [57]. Although there are some discrepancies on clinical competency, both residents and program directors believe that the pandemic would not affect their ability to pass the board examination and it is not necessary to extend the training course [39].

Because insufficient training was a concern, some assisted teaching methods were suggested and attempted by medical educators and clinical teachers. These assisted methods included simulations, online courses, the flipped classroom approach, and virtual reality/augmented reality [22, 75, 76]. Although these methods were adopted by many training program directors to compensate for the decreased clinical exposure and practice, the effect of doing so remained unknown because comparing learning outcomes between residency training in prepandemic and pandemic periods was impossible at this time. Extending training courses and delaying specialty board exams were considered options, but doing so could affect career planning and the quality of life of residents. The articles related to assisted teaching methods and adjustments were not included in our analysis because most of them were review articles rather than original works and failed to provide data regarding the effect. Although assisted teaching methods and adjusting training courses appear necessary, research must be conducted to determine the effectiveness of these methods.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, we only selected articles published in English, and some important information published in different languages may have been overlooked. Second, articles included in our study were mainly published in American and European countries. Lack of data from other regions, even those severely affected by the pandemic, could render the conclusion insufficiently comprehensive. Third, the articles included in our study were within 1 year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and some long-term effects of this pandemic may not be evident in this time period. Finally, no article compared the learning outcomes of residents between prepandemic and pandemic periods. The final performance of these residents remains unknown. Further studies are necessary to determine the learning outcomes of residency training during this pandemic.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly affected residency training globally, particularly surgical and interventional medical fields. Decreased clinical experience, reduced case volume, and disrupted education activities are major concerns in all fields. Although the publication of original studies investigating the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training is increasing, as of this writing, no study has compared the learning outcomes of residents between prepandemic and pandemic periods. Further study should be focused on the learning outcomes of residency training during the epidemic and evaluate the effectiveness of assisted teaching methods.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica database.

References

Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19 - implications for the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1483–8.

Di Gennaro F, Pizzol D, Marotta C, Antunes M, Racalbuto V, Veronese N, et al. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2690.

Carpenter CR, Mudd PA, West CP, Wilber E, Wilber ST. Diagnosing COVID-19 in the emergency department: a scoping review of clinical examinations, laboratory tests, imaging accuracy, and biases. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):653–70.

Greenland JR, Michelow MD, Wang L, London MJ. COVID-19 infection: implications for perioperative and critical care physicians. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1346–61.

Farooq RK, Rehman SU, Ashiq M, Siddique N, Ahmad S. Bibliometric analysis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) literature published in web of science 2019-2020. J Fam Community Med. 2021;28(1):1–7.

Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, Janga D, Dedeilias P, Sideris M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl):1603–11.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [cited 2021 20, March]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

Adesunkanmi AO, Ubom AE, Olasehinde O, Wuraola FO, Ijarotimi OA, Okon NE, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical residency training: perspective from a low-middle income country. World J Surg. 2021;45(1):10–7.

Alahmadi AS, Alhatlan HM, Bin Helayel H, Khandekar R, Al Habash A, Al-Shahwan S. Residents’ perceived impact of COVID-19 on Saudi ophthalmology training programs-a survey. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3755–61.

Alhaj AK, Al-Saadi T, Mohammad F, Alabri S. Neurosurgery residents’ perspective on COVID-19: knowledge, readiness, and impact of this pandemic. World Neurosurg. 2020;139:e848–e58.

Gabr AM, Li N, Schenning RC, Elbarbary A, Anderson JC, Kaufman JA, et al. Diagnostic and interventional radiology case volume and education in the age of pandemics: impact analysis and potential future directions. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(10):1481–8.

Balhareth A, AlDuhileb MA, Aldulaijan FA, Aldossary MY. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residency and fellowship training programs in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;57:127–32.

Cravero AL, Kim NJ, Feld LD, Berry K, Rabiee A, Bazarbashi N, et al. Impact of exposure to patients with COVID-19 on residents and fellows: an international survey of 1420 trainees. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1153):706–15.

Kahwash BM, Deshpande DR, Guo C, Panganiban CM, Wangberg H, Craig TJ. Allergy/immunology trainee experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: AAAAI work group report of the fellows-in-training committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(1):1–6.e1.

Zoia C, Raffa G, Somma T, Della Pepa GM, La Rocca G, Zoli M, et al. COVID-19 and neurosurgical training and education: an Italian perspective. Acta Neurochir. 2020;162(8):1789–94.

Roemmele C, Manzeneder J, Messmann H, Ebigbo A. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on endoscopy training in a tertiary care centre in Germany. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;11(6):454–7.

Pertile D, Gallo G, Barra F, Pasculli A, Batistotti P, Sparavigna M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on surgical residency programmes in Italy: a nationwide analysis on behalf of the Italian Polyspecialistic Young surgeons society (SPIGC). Updat Surg. 2020;72(2):269–80.

Mishra D, Nair AG, Gandhi RA, Gogate PJ, Mathur S, Bhushan P, et al. The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown on ophthalmology training programs in India - outcomes of a survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):999–1004.

Odedra D, Chahal BS, Patlas MN. Impact of COVID-19 on Canadian radiology residency training programs. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020;71(4):482–9.

Chang DG, Park JB, Baek GH, Kim HJ, Bosco A, Hey HWD, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic resident education: a nationwide survey study in South Korea. Int Orthop. 2020;44(11):2203–10.

Ellison EC, Spanknebel K, Stain SC, Shabahang MM, Matthews JB, Debas HT, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical training and learner well-being: report of a survey of general surgery and other surgical specialty educators. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(6):613–26.

Caruana EJ, Patel A, Kendall S, Rathinam S. Impact of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) on training and well-being in subspecialty surgery: a national survey of cardiothoracic trainees in the United Kingdom. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(4):980–7.

White EM, Shaughnessy MP, Esposito AC, Slade MD, Korah M, Yoo PS. Surgical education in the time of COVID: understanding the early response of surgical training programs to the novel coronavirus pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):412–21.

Bandi F, Karligkiotis A, Mellia J, Gallo S, Turri-Zanoni M, Battaglia P, et al. Strategies to overcome limitations in otolaryngology residency training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(12):3503–6.

Coyan GN, Aranda-Michel E, Kilic A, Luketich JD, Okusanya O, Chu D, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on thoracic surgery residency programs in the US: a program director survey. J Card Surg. 2020;35(12):3443–8.

Upadhyaya GK, Jain VK, Iyengar KP, Patralekh MK, Vaish A. Impact of COVID-19 on post-graduate orthopaedic training in Delhi-NCR. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(Suppl 5):S687–s95.

Rosen GH, Murray KS, Greene KL, Pruthi RS, Richstone L, Mirza M. Effect of COVID-19 on urology residency training: a nationwide survey of program directors by the society of academic urologists. J Urol. 2020;204(5):1039–45.

Bitonti G, Palumbo AR, Gallo C, Rania E, Saccone G, De Vivo V, et al. Being an obstetrics and gynaecology resident during the COVID-19: impact of the pandemic on the residency training program. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:48–51.

Aziz H, James T, Remulla D, Sher L, Genyk Y, Sullivan ME, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on surgical training across the United States: a national survey of general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):431–9.

Lo HY, Lin SC, Chaou CH, Chang YC, Ng CJ, Chen SY. What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency medicine residency training: an observational study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):348.

Johnson J, Chung MT, Stathakios J, Gonik N, Siegel B. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fellowship training: a national survey of pediatric otolaryngology fellowship directors. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;136:110217.

Robbins JB, England E, Patel MD, DeBenedectis CM, Sarkany DS, Heitkamp DE, et al. COVID-19 impact on well-being and education in radiology residencies: a survey of the association of program directors in radiology. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(8):1162–72.

Zheng J, Hundeyin M, He K, Sachs T, Hess DT, Whang E, et al. General surgery chief residents’ perspective on surgical education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Surgery. 2020;168(2):222–5.

Khusid JA, Weinstein CS, Becerra AZ, Kashani M, Robins DJ, Fink LE, et al. Well-being and education of urology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of an American National Survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(9):e13559.

Burks JD, Luther EM, Govindarajan V, Shah AH, Levi AD, Komotar RJ. Early changes to neurosurgery resident training during the COVID-19 pandemic at a large U.S. academic medical center. World Neurosurg. 2020;144:e926–e33.

Coleman JR, Abdelsattar JM, Glocker RJ. COVID-19 pandemic and the lived experience of surgical residents, fellows, and early-career surgeons in the American college of surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(2):119–35.e20.

Pawlak KM, Kral J, Khan R, Amin S, Bilal M, Lui RN, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on endoscopy trainees: an international survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):925–35.

Fero KE, Weinberger JM, Lerman S, Bergman J. Perceived impact of urologic surgery training program modifications due to COVID-19 in the United States. Urology. 2020;143:62–7.

Khan KS, Keay R, McLellan M, Mahmud S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on core surgical training. Scott Med J. 2020;65(4):133–7.

Clarke K, Bilal M, Sánchez-Luna SA, Dalessio S, Maranki JL, Siddique SM. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on training: global perceptions of gastroenterology and hepatology fellows in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Oct;66(10):3307-3311.

Ganigara M, Sharma C, Molina Berganza F, Joshi K, Blaufox AD, Hayes DA. Didactic education in paediatric cardiology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national fellow survey. Cardiol Young. 2021;31(3):377–80.

Ferrara M, Romano V, Steel DH, Gupta R, Iovino C, van Dijk EHC, et al. Reshaping ophthalmology training after COVID-19 pandemic. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(11):2089–97.

Huamanchumo-Suyon ME, Urrunaga-Pastor D, Ruiz-Perez PJ, Rodrigo-Gallardo PK, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on general surgery residency program in Peru: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;60:130–4.

Meghpara MK, Alapati A, Devanabanda B, Louis MA, Mandava N. Repurposing a small community hospital surgical residency program in an epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Surg. 2020;86(12):1623–8.

Osama M, Zaheer F, Saeed H, Anees K, Jawed Q, Syed SH, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on surgical residency programs in Pakistan; a residents’ perspective. Do programs need formal restructuring to adjust with the “new normal”? A cross-sectional survey study. Int J Surg. 2020;79:252–6.

Paesano N, Santomil F, Tobia I. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Ibero-American urology residents: perspective of American confederation of urology (CAU). Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(suppl.1):165–9.

Homer NA, Epstein A, Somogyi M, Shore JW. Oculoplastic fellow education during the COVID-19 crisis. Orbit. 2020:1–5.

Poyiadji N, Klochko C, LaForce J, Brown ML, Griffith B. COVID-19 and radiology resident imaging volumes-differential impact by resident training year and imaging modality. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(1):106–11.

Monroig-Bosque PDC, Hsu JW, Lin MS, Shehabeldin AN, Rogers JT, Kim CF, et al. Pathology trainee redeployment and education during the COVID-19 pandemic: An institutional experience. Acad Pathol. 2020;7:2374289520953548.

Megaloikonomos PD, Thaler M, Igoumenou VG, Bonanzinga T, Ostojic M, Couto AF, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic and trauma surgery training in Europe. Int Orthop. 2020;44(9):1611–9.

Pelargos PE, Chakraborty A, Zhao YD, Smith ZA, Dunn IF, Bauer AM. An evaluation of neurosurgical resident education and sentiment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a north American survey. World Neurosurg. 2020;140:e381–e6.

Huntley RE, Ludwig DC, Dillon JK. Early effects of COVID-19 on oral and maxillofacial surgery residency training-results from a national survey. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(8):1257–67.

Rothrock RJ, Maragkos GA, Schupper AJ, McNeill IT, Oermann EK, Yaeger KA, et al. By the numbers analysis of effect of COVID-19 on a neurosurgical residency at the epicenter. World Neurosurg. 2020;142:e434–e9.

Veerasuri S, Vekeria M, Davies SE, Graham R, Rodrigues JCL. Impact of COVID-19 on UK radiology training: a questionnaire study. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(11):877.e7–e14.

Shah S, Castro-Dominguez Y, Gupta T, Attaran R, Byrum GV 3rd, Taleb A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interventional cardiology training in the United States. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(5):997–1005.

Gupta T, Nazif TM, Vahl TP, Ahmad H, Bortnick AE, Feit F, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interventional cardiology fellowship training in the New York metropolitan area: a perspective from the United States epicenter. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97(2):201–5.

Guo T, Kiong KL, Yao C, Windon M, Zebda D, Jozaghi Y, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on otolaryngology trainee education. Head Neck. 2020;42(10):2782–90.

An TW, Henry JK, Igboechi O, Wang P, Yerrapragada A, Lin CA, et al. How are Orthopaedic surgery residencies responding to the COVID-19 pandemic? An assessment of resident experiences in cities of major virus outbreak. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(15):e679–e85.

Singla VK, Jain S, Ganeshan R, Rosenfeld LE, Enriquez AD. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiac electrophysiology training: a survey study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2021;32(1):9–15.

Aljuboori ZS, Young CC, Srinivasan VM, Kellogg RT, Quon JL, Alshareef MA, et al. Early effects of COVID-19 pandemic on neurosurgical training in the United States: a case volume analysis of 8 programs. World Neurosurg. 2021;145:e202–e8.

WHO Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) 31, July. 2020 [cited 2021 20, March]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

Bregman DE, Cook T, Thorne C. Estimated national and regional impact of COVID-19 on elective case volume in aesthetic plastic surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(3):358–69.

Lewicki P, Basourakos SP, Al Awamlh BAH, Wu X, Hu JC, Schlegel PN, et al. Estimating the impact of COVID-19 on urology: data from a large nationwide cohort. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2021;25:52–6.

Swiatek PR, Weiner J, Alvandi BA, Johnson D, Butler B, Tjong V, et al. Evaluating the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sports surgery fellowship education. Cureus. 2021;13(1):e12943.

Angoulvant F, Ouldali N, Yang DD, Filser M, Gajdos V, Rybak A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact caused by school closure and national lockdown on pediatric visits and admissions for viral and non-viral infections, a time series analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):319–22.

Donovan RL, Tilston T, Frostick R, Chesser T. Outcomes of orthopaedic trauma services at a UK major trauma centre during a national lockdown and pandemic: the need for continuing the provision of services. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e11056.

Kamine TH, Rembisz A, Barron RJ, Baldwin C, Kromer M. Decrease in trauma admissions with COVID-19 pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):819–22.

Banerjee S, Tarantini G, Abu-Fadel M, Banerjee A, Little BB, Sorajja P, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 catheterization laboratory survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(15):e017175.

Chai N, Tang X, Linghu E, Feng J, Ye L, Wu Q, et al. The influence of the COVID-19 epidemic on the gastrointestinal endoscopy practice in China: a national survey. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(12):6524–31.

Jeffery MM, D'Onofrio G, Paek H, Platts-Mills TF, Soares WE 3rd, Hoppe JA, et al. Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1328–33.

Soo RJJ, Chiew CJ, Ma S, Pung R, Lee V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1933–5.

Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, Seo SK. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1272–7.

Michael Coughlan PC, Ryan F. Survey research: process and limitations. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16(1):9–15.

Shah S, Diwan S, Kohan L, Rosenblum D, Gharibo C, Soin A, et al. The technological impact of COVID-19 on the future of education and health care delivery. Pain Physician. 2020;23(4s):S367–s80.

Wilcha RJ. Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 crisis: systematic review. JMIR Med Educ. 2020;6(2):e20963.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital. We are thankful to our colleagues who provided their expertise, which greatly assisted the research, although they may not agree with all the interpretations provided in this paper.

Prior presentations

This research has not been presented previously.

Funding

There is no funding to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SYC and HYL; Data curation: HYL and SKH; Formal analysis: SYC and SKH; Figure preparation: SKH; Investigation: SYC, HYL and SKH; Writing-original draft: HYL and SKH; Writing- review&editing: SYC. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB: 202100338B1).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Information of the included original articles.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, SY., Lo, HY. & Hung, SK. What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on residency training: a systematic review and analysis. BMC Med Educ 21, 618 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03041-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03041-8