Abstract

Background

Among Chinese medical students, there is a high prevalence of mental health-related issues and low empathy. Effective strategies to improve this situation are lacking. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of the intervention courses designed to enhance the mental health and empathy of senior Chinese medical students.

Methods

A total of 146 3rd - and 4th -year medical students were randomized to an intervention group (n = 74) and a control group (n = 72). A pilot study including 5 pre-clinical students and 5 interns was first carried out to determine the themes and content of the intervention courses. The designed courses were delivered in the intervention group once a month three times, while the control group had no specific intervention. Five self-assessment questionnaires, including the General Self-Efficacy (GSE) scale, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 8 (SF-8), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), and Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Care Provider Student version (JSE-HPS), were completed by the students before and one month after the courses to evaluate their levels of self-efficacy (SE), quality of life (QoL), depression, burnout, and empathy, respectively. Qualitative data were collected via e-mail two years after the intervention.

Results

Compared to the control group, the intervention group showed significantly higher scores for empathy (111.0 [IQR 102.0, 118.0] vs. 106.0 [IQR 93.0, 111.5]; P = .01) and QoL (32.0 [IQR 28.0, 35.0] vs. 29.5 [IQR 26.0, 34.0]; P = .04). The rate of depression was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (13.5 % vs. 29.2 %; chi-square test, P = .02). However, no significant differences in self-efficacy (25.6 ± 4.8 vs. 24.3 ± 6.3; P = .16) or burnout (27.0 % vs. 34.7 %; Chi-square test, P = .31) were observed between the two groups.

Conclusions

The intervention courses had a positive impact on mental well-being and empathy in senior Chinese medical students, which might help provide novel information for their incorporation into the medical school curriculum.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02645643; Date of registration: 05/01/2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many stress factors, including long study hours, frequent examinations and deteriorating patient-physician communication, make medical students vulnerable to mental health problems [1,2,3,4]. Accumulating literature has shown that a significant proportion of medical students have different degrees of mental health problems [5, 6]. In addition, the prevalence of depression has been found to be significantly higher among medical students (22–36 %) than among precollege students and the general population (2–16 %) [7,8,9,10]. It has also been well documented that medical students are more susceptible to burnout associated with a noticeable lack of self-efficacy (SE), which affects their academic performance, clinical empathy and overall quality of life (QoL) [11]. In China, these mental health-related issues have been further exacerbated by the deteriorating patient-doctor relationship, as reflected by the intensive violent incidents perpetrated by the patients in the hospitals [12, 13]. Frequent medico-legal disputes have generated a heavy psychological burden and stress for medical students in China [14, 15] and have negatively impacted students’ passion and confidence in pursuing their future medical careers [13, 16]. The lack of communication skills due to a low level of empathy is an important factor contributing to a tense patient-physician relation in China [17, 18]. In addition, reduced empathy further compromises students’ clinical ability and performance [14, 15].

Although many previous reports have raised extensive concerns regarding the mental health of medical students, effective intervention strategies are lacking [16]. In recent years, several randomized controlled studies have investigated the ability of interventions using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) to reduce mental distress and burnout and improve coping skills [19, 20]. In addition, various interventions, including yoga, psychological counselling and Williams LifeSkills training, have also been reported to have positive effects on the improvement of stress, depression and quality of life [2, 21,22,23]. While these studies provide important data for our understanding of the modulation of mental health, there are some limitations in the work. Previous trials often focused on the short-term effects; nevertheless, the long-term effects of the designed interventions were unclear. More importantly, most of the interventions were designed without detailed research on the mental difficulties of the medical students. In this context, the intervention might not have been precise, which could have affected the intervention efficacy. Moreover, except for MBSR, many of the interventions were not delivered by trained clinicians, which might lead to failure in emotion transmission that impairs teaching efficiency and the learning experience in medical education [24, 25]. Therefore, a problem-oriented educational intervention that precisely targets the specific medical student population with measurable short- and long-term efficacy should be explored and developed.

In China, medical students usually spend five years in their undergraduate courses and begin clinical work in their third year. In addition to the heavy academic burden, this school-clinic transition increases the study load and threatens mental well-being [17, 26]. Moreover, 3rd - and 4th -year students engage in direct professional patient-doctor communication. However, our university offers only some courses on the medical humanities for first-year students, and these courses mainly focus on theories of medical development and modern patient-doctor relations. Communication skills training is lacking for pre-clinical students. Higher frequencies of depression and burnout and lower empathy and sense of personal achievement have been reported in senior medical students compared to those in junior medical students [17, 18, 27]. Nevertheless, related randomized intervention studies carried out with Chinese medical students are very limited, and thus, they are urgently needed.

In the current study, we aimed to develop a set of physician-guided intervention courses and perform a prospective randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention, to improve the mental well-being and empathy of 3rd - and 4th -year medical students in China.

Methods

Development of the intervention

To make the intervention courses context-specific, we first attempted to understand the psychological disturbances of the 3rd - and 4th -year medical students in our hospital. We randomly recruited five pre-clinical medical students (3rd year) and five interns (4th year) to participate in a pilot study for preliminary data collection to determine the themes of the intervention courses. We met with the pilot study participants and discussed their impressions of their current clinical work and related mental difficulties for three times within three months. The students often mentioned a lack of motivation and achievement in daily repetitive medical work, pressure to cope with the doctor-patient relationship and the need to acquire action-oriented strategies or skills to help them face the workload and potential medical negligence. Using an iterative process of coding scheme and discussion to resolve disagreements [28, 29], we summarized the key concepts and organized the topics into three modules: “Establishing a Sense of Achievement”, “Means for Efficient Patient-Doctor Communication”, and “Strategies to Manage Medical Errors”.

It has been reported that the narrative storytelling, a variant of appreciative inquiry, helped establish the students’ faith understanding and internalization [28]. Furthermore, in consideration of the importance of the context specificity and the emotion transmission, we therefore introduced three experienced clinicians to narrate stories that were related to the identified themes based on their own real clinical experience, including the positive aspects of medical practice, strategies for efficient patient communication and the responses to medical errors (Additional file 1).

Building on previous literature [30,31,32], we further included facilitated discussion groups that incorporated elements of mindfulness, shared experience, and small-group learning in the intervention. The same general structure was followed in each course: (1) check-in and welcome, (2) environment preparation (e.g., leisure time, creation of a friendly atmosphere, and a simple reflective exercise), (3) story narration, (4) skills and solutions learning, (5) facilitated group discussion, and (6) summary and checkout.

Investigation of the intervention efficacy

Participants

This was a single-centre, randomized controlled study carried out in the Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, between March 2016 and June 2016. The enrolment criteria included (1) third- and fourth-year medical students who (2) were studying major subjects of clinical medicine and (3) lacked a history of mental illness. Finally, a total of 146 medical students were enrolled. All the enrolled participants read and signed written informed consent before participating in the study.

Sample size

The power and sample size were calculated with a two-sided chi-square test with a 5 % significance level. We estimated that with 64 students assigned to each group, the study would have 80 % power to detect 5-point differences for the primary end point of empathy between the two groups, with a standard deviation of 10. In the current study, the sample size was 146, rendering 85 % power to detect a 2.5-point difference in the quality of life scale and 64 % power to detect a 15.7 % difference in depression between the two groups, with a standard deviation of 5.

Randomization

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 74) and control (n = 72) groups according to the randomization results, which were sealed in an opaque envelope delivered by the co-investigators. The randomization coding list was generated by a simple randomization allocation method, the PLAN procedure (SAS, version 9.4, USA). Each student was assigned a number, which was linked to the corresponding contact information kept by the third-party supervisor. Neither the students nor their teachers were blind to the allocated group due to the interactive schedules between the two groups.

Intervention and control

The intervention courses were delivered every month for three months after regular medical courses. Students in the intervention group were divided into three small groups (~ 25 students/group) based on the order of their code numbers, and each group was guided by a corresponding lecture. Each course lasted approximately 60 min. Students in the control group were also guided by a teacher and were encouraged to discuss their difficulties in clinical work and school life. This was done in a leisurely, friendly atmosphere. Correspondingly, the teacher shared related experiences or gave suggestions for dealing with these problems. However, there was no structural course form provided and no predefined topics were discussed.

Data collection

In this trial, we used five validated questionnaires to evaluate self-efficacy (SE), quality of life (QoL), depression, burnout and empathy. All participants were asked to complete the self-assessment scales and provide their individual randomized number on the questionnaires that were administered before and one month after the whole intervention courses. The following scales were used.

General self-efficacy scale

SE was measured by the General Self-Efficacy (GSE) scale. The GSE scale is designed to measure a broad, stable sense of personal competence to effectively deal with a variety of stressful situations [33]. The scale is composed of 10 itemized questions that are answered on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (score 1) to strongly agree (score 6). A higher total score indicates a higher level of SE.

Medical outcomes study short form 8

QoL was measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 8 (SF-8). The SF-8 is a valid QoL survey that covers the same eight domains of the SF-36 but in a shorter (eight question) form [34]. The domains covered by the SF-8 Likert-type scale include physical function, limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, energy/fatigue, social function, limitations due to emotional problems, psychological distress and mental well-being. The pain domain score ranges from 1 to 6, while the other domain scores range from 1 to 5. Higher scores represented better physical state and mental state.

Patient health questionnaire-9

Depression was measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 has 9 questions assessing the following symptoms: depression (anhedonia and depressed mood), suicidal tendency (suicidal thoughts), physical symptoms (trouble sleeping or concentrating, fatigue, changes in appetite, and a feeling of being slowed down or restless) and feelings of guilt or worthlessness over the past two weeks. A total score of > 9 points or the presence of suicidal tendency indicated the existence of depressive symptoms.

Maslach burnout inventory

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is a valid and widely used standard survey to measure burnout [35,36,37]. Burnout comprises three domains: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA). The MBI uses a 7-point Likert scale and includes 22 items evaluating all three domains (the score range for EE is 0–54, the score range for DP is 0–30 and the score range for PA is 0–48). Medical students who score ≥ 27 in the EE domain or ≥ 10 in the DP domain are identified as having at least one manifestation of professional burnout [38].

Jefferson scale of empathy-health care provider student version

We measured empathy with the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Care Provider Student version (JSE-HPS), which includes 20 items answered on a 7-point Likert scale. The students were asked to score each item according to their level of agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Ten items are negatively worded and reverse scored. The total JSE-HPS score ranges from 20 to 140, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of empathy [39]. The itemized questions in each survey were initially translated into Chinese for data collection and then translated back into English by bilingual researchers at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University to ensure the accuracy of the translation. All of the questionnaires, including the General Self-Efficacy (GSE) scale [40, 41], the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 8 (SF-8) [42], the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [43,44,45,46], and the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Care Provider Student version [27], have been validated for the Chinese population.

Follow-up

To evaluate the long-term impact of the intervention courses, we contacted all the intervention group students two years after the intervention (June 2018) by e-mail. The students were requested to reflect on the intervention courses by responding to the following three items: (1) Please write down the most impressive story you remember from the intervention courses. (2) Which aspect of the intervention courses influenced you the most? (3) How did you apply the strategies from the intervention courses in your daily clinical practice? The third question was used to evaluate if the interventions were internalized in the students. We collected all the answers from the e-mail. The core sentences and words that indicated the student’s mental or emotional reflection on the intervention were extracted. These concepts were further discussed, classified and summarized by the authors.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaires with missing information on three or more items were excluded from the subsequent analysis. If the scores of a few scale items were missing, the medians of the scores of the same items from the remaining students were used to replace the missing data. The baseline characteristics of the participants were described with the mean (SD) if the variable followed a normal distribution, and if the data did not follow a normal distribution, the median (IQR) was used. The independent sample t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare differences in the continuous variables between two groups, while the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse the categorical variables. The significant differences between the baseline and follow-up scores for each outcome for both the intervention and control groups were also determined using the paired t test, and the differences between the baseline and follow-up scores were calculated and compared. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Cohort and baseline characteristics

We initially recruited 160 3rd - and 4th -year medical students. After screening, a total of 146 students were enrolled and randomized to two arms (74 students in the intervention group and 72 students in the control group), as shown in Fig. 1. Among all collected surveys, 15 missing values were found, and none of the scales were excluded from the analysis. No significant differences in gender, grade or age were observed between the intervention and control groups. In addition, the baseline levels of SE (26.1 ± 4.4 vs. 25.8 ± 5.6; P = .76), QoL (31.0 [IQR 28.5, 34.0] vs. 31.0 [IQR 29.0, 34.0]; P = .62), depression (15.3 % vs. 24.3 %; chi-square test, P = .17), burnout (33.3 % vs. 35.1 %; chi-square test, P = .82) and empathy (110.5 [IQR 101.5, 119] vs. 110 [IQR 103, 116]; P = .98) between the two groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Short-term outcomes of the randomized arms

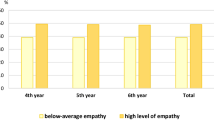

Compared to the students in the control group, the students in the intervention group had significantly higher scores for QoL (32.0 [IQR 28.0, 35.0] vs. 29.5 [IQR 26.0, 34.0]; P = .04) and empathy (111.0 [IQR 102.0, 118.0] vs. 106.0 [IQR 93.0, 111.5]; P = .01) and a lower rate of depression (13.5 % vs. 29.2 %; chi-square test, P = .02) (Fig. 2; Table 2). The burnout score in the intervention group was lower than that in the control group (45.1 ± 13.6 vs. 49.6 ± 13.1; P = .04); however, no significant difference was observed in the burnout rate between the two groups (27.0 % vs. 34.7 %; chi-square test, P = .31) (Table 2). The students in the two groups had similar SE scores, with no significant difference (25.6 ± 4.8 vs. 24.3 ± 6.3; P = .16) (Table 2).

We also compared the baseline and follow-up scores for each outcome for both the intervention and control groups to determine whether there were significant differences. The data showed from baseline to one month after intervention, the control group had decreased scores for SE (1.79, [95 % CI: 0.01, 3.57], p = .05), QoL (1.9, [95 % CI: 0.23, 3.58], p = .027), and empathy (5.44, [95 % CI: 5.81, 10.08], p = .023); increased depression scores (-1.68, [95 % CI: -2.91, -0.4], p = .008); and unchanged levels of burnout (-0.54, [95 % CI: -4.46, 3.37], p = .787).

Compared to baseline, at one month after intervention, the intervention group had decreased depression scores (1.12, [95 % CI: 0.5, 2.45], p = .028) and unchanged levels of SE (0.15, [95 % CI: -1.5, 1.79], p = .862), QoL (0.48, [95 % CI: -0.97, 1.92], p = .52), empathy (2.04, [95 % CI: -1.69, 5.76], p = .023) and burnout (2.71, [95 % CI: -0.62, 6.03], p = .787).

Long-term efficacy of the intervention courses

We obtained twenty-one replies at follow-up, for a response rate of 25.6 %. For the first item (Please write down the most impressive story you remember from the intervention course), it was striking that 15 of the 21 students referred to one of the stories from the “Means for Efficient Patient-Doctor Communication” module. The stories in the “Strategies to Manage Medical Errors” were recalled by five students, while one student was impressed with the story from the “Establishing a Sense of Achievement” module (Additional file 2). In response to the second question (Which aspect of the intervention courses influenced you the most?), all the students reported the positive aspects of the intervention courses and their positive and constructive influence on their daily practice and long-term careers. In addition to learning the strategies and skills, the students also reported the importance of learning how to establish an emotional connection with the patients. They reflected on the shift in their perception of doctor-patient relations and medical errors. In response to the third question (How did you apply the strategies from the intervention courses in your daily clinical practice?), most of the students reported that they learned to pay special attention to their teachers’ conversation skills, as well as the expressions and attitudes of patients and their families in their daily work. In addition, careful history taking, bodily examinations and multidisciplinary clinical decisions were also mentioned as important for reducing medical errors.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of an educational intervention on mental health and empathy of senior Chinese medical students. Generally, the problem-oriented and physician-guided courses showed positive effects on students’ well-being, as evidenced by significantly improved QoL, depression and empathy.

In China, the 3rd and 4th years of clinical medical education are an important transitional stage. In our centre, 3rd - and 4th -year students have the heaviest academic load (e.g., they must pass the final examinations for 9 clinical subjects and various Objective Structured Clinical Examination [OSCE] tests). In addition, the 3rd - and 4th -year students are just at the very beginning of their clinical work and have little clinical experience in the communication with the patients, which can bring them a lot of stress. Interventions should be developed to help students go through this stage. Several previous trials have reported some useful methods that reduce distress or stress, such as MBSR-based exercises, psychological counselling and peer communication [19, 20, 22, 47]. Nevertheless, knowledge of mental problems or difficulties among this subset of Chinese medical students is limited. To make the intervention context-specific, we performed a pre-trial pilot study, which offered important clues indicating that these students need more clinical guidance and communication skill support, in addition to psychological comfort. The pilot study has provided direct data for the establishment of the precise intervention courses targeting this subset of students. The improved QoL, depression and empathy at one month after the intervention and the positive effects on the perception and clinical ability observed for some of the students after 2 years revealed the efficacy of the intervention courses. Our data provide evidence that the problem-oriented educational intervention might be useful. In addition to the reported methods, the method presented in the current study could be explored to address mental health or empathy problems in a specific medical student population.

Another difference in the design of the present study from that of most of the previous work is that all intervention courses are guided by experienced physicians. We take emotional transmission and sincerity into account in this trial since emotion has been found to have a positive effect on learning efficiency and internalization of clinical skills and knowledge [24, 48]. It is inspiring to find that the courses helped some of the students in their future clinical practice. This result indicates the importance of emotion and professionalism in interventions involving senior Chinese medical students.

Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of mental health problems in medical students was significantly higher than that in the general population and was even higher in senior medical students [49,50,51]. Similarly, we also observed a high prevalence of depression and burnout in this study. After the intervention, compared to the control group, the intervention group showed significant improvement in QoL and depression. Depression was also reduced after the courses compared to that at baseline in the intervention group, indicating a benefit in the relief of mental stress. Notably, we observed that the depression rate of students in the control group significantly increased. A possible explanation might be that the final exams were approaching, which placed a considerable amount of pressure on the students, as the 3rd- and 4th-year medical students in our university needed to pass 9 clinical subjects and various OSCE-based tests for their final examinations. Such pressure also likely explained why not only depression but also SE, QoL, and empathy worsened in the control group, while the mental health levels of the students in the intervention group showed improvement or unchanged levels after courses compared to those at baseline. This phenomenon might imply the positive effect of the intervention to help students face daily stress and maintain a stable mental state. In the study, SE and burnout did not show significant improvement, which could be attributed to the relatively short duration of the intervention courses. Future studies with longer intervention courses are required.

Empathy is another important ability of medical students, especially for senior Chinese medical students. Over the past 20 years, many violent incidents perpetrated by patients have been reported, which has made being a doctor in China a high-risk job [13, 26] and has affected students’ faith in their careers [15]. Poor doctor-patient relationships might lower students’ clinical empathy, which could further exacerbate doctor-patient communication, ultimately affecting patient prognosis [52, 53]. Empathy could be of great help in improving doctor-patient communication to achieve the best mutual understanding [54], and it has also been found to be important to patient care by enhancing patient satisfaction, comfort, self-efficacy and trust, leading to accurate diagnosis, shared decision making and therapy adherence [55]. In this study, we introduced patient-doctor communication skills by narrating and sharing real stories, eventually effectively improving the empathy of medical students in the intervention group compared to that of students in the control group. More importantly, as described in the follow-up e-mails, the students remembered the stories and emphasized skills learning two years after the courses had ended.

This study also has several limitations. First, this is a single-centre trial. Multicentre studies should be carried out in the future to further validate the efficacy of similar interventions. In addition, the Chinese versions of all five scales have been validated in previous studies [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. However, it is difficult to guarantee the complete preservation of the original intention due to translation. Third, there are a few missing data for some scale items, but the proportion is less than 1 %. Another minor limitation is that it is difficult to prevent the potential communication between the students in the control and intervention group after courses. If the students in the intervention group had deep talk with the students in the control group, it might lead to bias of the short-term outcomes.

Conclusions

Intervention courses guided by clinicians sharing real-life experiences significantly improve QoL, promote empathy and reduce depression among senior Chinese medical students. Our results pave the way for the development of a novel strategy for course reform in the education curriculum in Chinese medical schools by adding accessible, lowcost and easy-to-implement educational interventions to improve stress-related mental health and empathy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GSE:

-

General Self-Efficacy

- SF-8:

-

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 8

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- JSE-HPS:

-

Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health care Provider Student version

- SE:

-

Self-efficacy

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- MBSR:

-

Mindfulness-based stress reduction

- EE:

-

Emotional exhaustion

- DP:

-

Depersonalization

- PA:

-

Personal accomplishment

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- OSCE:

-

Objective Structured Clinical Examination

References

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–73.

Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158–64.

Yusoff MS, Abdulrahim AF, Yaacob MJ. Prevalence and Sources of Stress among Universiti Sains Malaysia Medical Students. Malays J Med Sci. 2010;17(1):30–7.

Sobowale K, Zhou N, Fan J, Liu N, Sherer R. Depression and suicidal ideation in medical students in China: a call for wellness curricula. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:31–6.

Yusoff MS, Abdulrahim AF, Baba AA, Ismail SB, Matpa MN, Esa AR. Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among prospective medical students. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6(2):128–33.

Frajerman A, Morvan Y, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Chaumette B. Burnout in medical students before residency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatr. 2019;55:36–42.

Kumar GS, Jain A, Hegde S. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors using Beck Depression Inventory among students of a medical college in Karnataka. Indian J Psychiatr. 2012;54(3):223–6.

Ngasa SN, Sama CB, Dzekem BS, Nforchu KN, Tindong M, Aroke D, Dimala CA. Prevalence and factors associated with depression among medical students in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):216.

Mukhtar F, Oei TP. A review on assessment and treatment for depression in malaysia. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:123642.

Smith CK, Peterson DF, Degenhardt BF, Johnson JC. Depression, anxiety, and perceived hassles among entering medical students. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(1):31–9.

Mazurkiewicz R, Korenstein D, Fallar R, Ripp J. The prevalence and correlations of medical student burnout in the pre-clinical years: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17(2):188–95.

Sun J, Liu S, Liu Q, Wang Z, Wang J, Hu CJ, Stuntz M, Ma J, Liu Y. Impact of adverse media reporting on public perceptions of the doctor-patient relationship in China: an analysis with propensity score matching method. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e22455.

He AJ, Qian J. Explaining medical disputes in Chinese public hospitals: the doctor-patient relationship and its implications for health policy reforms. Health Econ Policy Law. 2016;11(4):359–78.

Jie L. New generations of Chinese doctors face crisis. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1878.

Zeng J, Zeng XX, Tu Q. A gloomy future for medical students in China. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1878.

Wan P, Long E. Expectations of medical students in China. Lancet. 2016;387(10025):1275.

Li D, Xu H, Kang M, Ma S. Empathy in Chinese eight-year medical program students: differences by school year, educational stage, and future career preference. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):241.

Blatt B, Kallenberg G, Lang F, Mahoney P, Patterson J, Dugan B, Sun S. Found in translation: exporting patient-centered communication and small group teaching skills to China. Med Educ Online. 2009;14:6.

de Vibe M, Solhaug I, Tyssen R, Friborg O, Rosenvinge JH, Sørlie T, Bjørndal A. Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:107.

Kuhlmann SM, Huss M, Bürger A, Hammerle F. Coping with stress in medical students: results of a randomized controlled trial using a mindfulness-based stress prevention training (MediMind) in Germany. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):316.

Prasad L, Varrey A, Sisti G. Medical Students’ Stress Levels and Sense of Well Being after Six Weeks of Yoga and Meditation. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;2016:9251849.

Thompson D, Goebert D, Takeshita J. A program for reducing depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in medical students. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1635–9.

Li C, Chu F, Wang H, Wang XP. Efficacy of Williams LifeSkills training for improving psychological health: a pilot comparison study of Chinese medical students. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2014;6(2):161–9.

Lemoine ER, Nassim JS, Rana J, Burgin S. Teaching & Learning Tips 4: Motivation and emotion in learning. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(2):233–6.

Kaplan-liss E, Lantz-gefroh V, Bass E, Killebrew D, Ponzio NM, Savi C. O’connell C. Teaching Medical Students to Communicate With Empathy and Clarity Using Improvisation. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):440–3.

Yu Pan X, Yang J, He Y, Gu X, Zhan H, Gu Q, Qiao D, Zhou, Huimin Jin. To be or not to be a doctor, that is the question: a review of serious incidents of violence against doctors in China from 2003–2013. J Public Health. 2015;23(2):111–6.

Wen D, Ma X, Li H, Liu Z, Xian B, Liu Y. Empathy in Chinese medical students: psychometric characteristics and differences by gender and year of medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:130.

Quaintance JL, Arnold L, Thompson GS. What students learn about professionalism from faculty stories: an “appreciative inquiry” approach. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):118–23.

Glase BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, Romanski SA, Hellyer JM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527–33.

Warnecke E, Quinn S, Ogden K, Towle N, Nelson MR. A randomised controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on medical student stress levels. Med Educ. 2011;45(4):381–8.

Ellman MS, Fortin AH, Putnam A, Bia M. Implementing and Evaluating a Four-Year Integrated End-of-Life Care Curriculum for Medical Students. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(2):229–39.

Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy: thought control of action. Washington DC: Hemisphere; 1992.

Turner-bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):1003–12.

Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Moutier C, Durning SJ, Power DV, Massie FS, Eacker A, Thomas MR, Satele D, Sloan JA, et al. A multi-institutional study exploring the impact of positive mental health on medical students’ professionalism in an era of high burnout. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1024–31.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Power DV, Durning S, Moutier C, Massie FS, Harper W, Eacker A, Szydlo DW, Sloan JA, et al. Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: a multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):94–102.

Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2880–9.

Maslach C JSLM. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1434–8.

Song X, Ding N, Jiang N, Li H, Wen D. Time use in out-of-class activities and its association with self-efficacy and perceived stress: data from second-year medical students in China. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1759868.

Guo YF, Zhang X, Plummer V, Lam L, Cross W, Zhang JP. Positive psychotherapy for depression and self-efficacy in undergraduate nursing students: a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Mental Health Nurs. 2017;26(4):375–83.

Zhong X, Liu Y, Pu J, Tian L, Gui S, Song X, Xu S, Zhou X, Wang H, Zhou W, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life among Chinese medical postgraduates: a national cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(8):1015–27.

Zhang YL, Liang W, Chen ZM, Zhang HM, Zhang JH, Weng XQ, Yang SC, Zhang L, Shen LJ, Zhang YL. Validity and reliability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia Pac Psychiatr. 2013;5(4):268–75.

Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, Zhang G, Zhou Q, Zhao M. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):539–44.

Wang Q, Wang L, Shi M, Li X, Liu R, Liu J, Zhu M, Wu H. Empathy, burnout, life satisfaction, correlations and associated socio-demographic factors among Chinese undergraduate medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):341.

Chunming WM, Harrison R, Macintyre R, Travaglia J, Balasooriya C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review of experiences in Chinese medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):217.

Menon V, Sarkar S, Kumar S. Barriers to healthcare seeking among medical students: a cross sectional study from South India. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1079):477–82.

Mcconnell MM, Eva KW. The role of emotion in the learning and transfer of clinical skills and knowledge. Acad Med. 2012;87(10):1316–22.

Pan XF, Wen Y, Zhao Y, Hu JM, Li SQ, Zhang SK, Li XY, Chang H, Xue QP, Zhao ZM, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its correlates among medical students in China: a national survey in 33 universities. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(7):882–9.

Wilkinson TJ, Gill DJ, Fitzjohn J, Palmer CL, Mulder RT. The impact on students of adverse experiences during medical school. Med Teach. 2006;28(2):129–35.

Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, Massie FS, Eacker A, Moutier C, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Dyrbye LN. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520–5.

Casas RS, Xuan Z, Jackson AH, Stanfield LE, Harvey NC, Chen DC. Associations of medical student empathy with clinical competence. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):742–7.

Howick J, Moscrop A, Mebius A, Fanshawe TR, Lewith G, Bishop FL, Mistiaen P, Roberts NW, Dieninytė E, Hu XY, et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2018;111(7):240–52.

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Roter D, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Eggly S, Moore RD, Beach MC. Clinician empathy is associated with differences in patient-clinician communication behaviors and higher medication self-efficacy in HIV care. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(2):220–6.

Quince T, Thiemann P, Benson J, Hyde S. Undergraduate medical students’ empathy: current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:443–55.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Sui Peng for the help of revising the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by MOOC Construction Project of Sun Yat-sen University in 2018 (number 80000-18832627).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR and JLG conceived the design. MK and HPX supervised the study. WC, WYC, ZHD and YBZ performed all procedures of the clinical trial. RR, JLG and YBZ analyzed the data. RR and ZHD wrote the manuscript. MK and HPX reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional ethic review board of Zhongshan School of Medicine and all enrolled participants read and signed the written informed consent before commencing the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rong, R., Chen, W., Dai, Z. et al. Improvement of the management of mental well-being and empathy in Chinese medical students: a randomized controlled study. BMC Med Educ 21, 378 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02813-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02813-6