Abstract

Background

Interacting with patients can elicit a myriad of emotions in health-care providers. This may result in satisfaction or put providers at risk for stress-related conditions such as burnout. The present study attempted to identify emotions that promote provider well-being. Following eudaimonic models of well-being, we tested whether certain types of emotions that reflect fulfilment of basic needs (self-worth, bonding with patients) rather than positive emotions in general (as suggested by hedonic models) are linked to well-being. Specifically, we hypothesized that well-being is associated with positive emotions directed at the self, which reflect self-worth, and positive as well as negative emotions (e.g., worry) directed at the patient, which reflect bonding. However, we expected positive emotions directed at an object/situation (e.g., curiosity for a treatment) to be unrelated to well-being, because they do not reflect fulfilment of basic needs.

Methods

Fifty eight physicians, nurses, and psychotherapists participated in the study. First, in qualitative interviews, they reported their emotions directed at the self, the patient, or an object/situation during distressing interactions with patients. These emotions were categorised into positive emotions directed towards the self, the patient, and an object/situation, and negative emotions directed towards the patient that reflect bonding. Second, providers completed questionnaires to assess their hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. The well-being scores of providers who did and did not experience these emotions were compared.

Results

Providers who experienced positive emotions directed towards the self or the patient had higher well-being than those who did not. Moreover, for the first time, we found evidence for higher well-being in providers reporting negative patient-directed emotions during distressing interactions. There was no difference between providers who did and did not experience positive object/situation-directed emotions.

Conclusions

These findings may point towards the importance of “eudaimonic” emotions rather than just positive emotions in interactions with patients. Emotions such as contentment with oneself, joy for the patient’s improvement, and, notably, grief or worry for the patient may build a sense of self-worth and strengthen bonding with the patient. This may explain their association with provider well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Caring for patients can elicit various emotions in health-care providers. While some of these emotions can result in positive provider outcomes such as satisfaction or professional fulfilment, others may put providers at risk for stress-related conditions such as burnout. These conditions are highly prevalent in health-care professions [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. For example, studies of physicians, nurses, and psychotherapists show that caring empathically for others may elicit feelings of joy, fulfilment, gratitude, and inspiration [8,9,10,11,12,13]. By contrast, situations such as treating suffering patients, breaking bad news, being exposed to the traumatic contents of patients’ histories, and losing patients to death may lead to doubt, grief, shock, and guilt [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Hence, health-care-related emotions clearly carry the potential for both positive and negative provider outcomes (e.g., satisfaction and burnout) [1, 22,23,24,25]. However, no previous study has assessed which of these emotions are associated with provider well-being. To elucidate this association, we look at two existing models of well-being.

According to the widespread hedonic model of well-being, experiencing high levels of positive emotions and low levels of negative emotions enhances well-being [26,27,28]. Although empirically supported, this hedonic model may not be sufficient in explaining well-being in health-care professionals. For example, are negative emotions such as grieving for patients indeed unfavourable for the provider? Or can they give a sense of meaning? Moreover, is it not also important to consider the target an emotion is directed at [29]? For example, positive emotions directed at oneself (e.g., pride in one’s performance) may have a larger effect on well-being than positive emotions directed at an object (e.g., curiosity about a disease). Taken together, it may be too simplistic to view positive emotions as “favourable” and negative emotions as “unfavourable” to well-being irrespective of their content and directedness. Therefore, more refined models are needed.

Expanding hedonic theories, Tamir and colleagues have highlighted the importance for well-being of emotions that serve eudaimonic purposes [30, 31]. In eudaimonic models of well-being, well-being results from realising one’s potential rather than from experiencing positive emotions. Realising one’s potential, also called positive functioning or flourishing, has been characterised by varying constructs such as environmental mastery, meaning in life, and personal growth [32,33,34,35,36]. Moreover, at the core of several of the eudaimonic well-being models are two constructs from basic needs theories [37, 38], which also reflect positive functioning [32,33,34,35,36]: The first concerns the need to feel valuable, lovable, and competent, here referred to as need for self-worth. The second concerns the need to be close and connected to others, here referred to as need for bonding [39]. As suggested by Tamir and colleagues, emotions that reflect basic needs serve eudaimonic purposes and may therefore be associated with well-being [30, 31].

No research has yet defined the kinds of emotions that reflect the fulfilment of these two basic needs. However, Fischer and Manstead [40] have made important contributions to our understanding of the social functions of emotions. According to these authors, emotions can serve the goal of affiliation or social distancing. Prototypical examples for emotions that enhance closeness or affiliation between individuals are love and happiness in terms of sharing positive experiences, and sadness when seeking support. In contrast, anger, contempt, or fear of another person are emotions that foster social distance [40].

The concept of Fischer and Manstead could be applied to the health-care context. Emotions of affection and joy directed towards the patient may serve affiliative functions and thus reflect fulfilment of the need for bonding. Fischer and Manstead argue that negative emotions can also serve affiliative functions [40]. We therefore propose that patient-directed negative emotions of fear for the patient (e.g., worrying) or sadness for the patient (e.g., grieving) also reflect social bonding. In contrast, emotions such as anger, dislike, and disappointment directed towards the patient may instead serve social distancing functions.

The other need proposed in eudaimonic models of well-being is the need for self-worth. It is known that emotions may serve a self-evaluative function [41, 42]. For example, people who attribute success to their own abilities or behaviours experience pride (see also [43]). Hence, pride is a positive self-evaluative emotion. In contrast, people who attribute failure to their inability or wrong behaviour experience guilt. Guilt is thus a negative self-evaluative emotion [42, 43]. Based on these considerations, we propose that positive emotions of affection and joy directed towards the self (e.g., liking oneself as a person, satisfaction or pride with one’s performance) are positive self-evaluations. Therefore, these emotions promote high self-worth. In contrast, negative self-directed emotions (e.g., anger or doubt about one’s performance) are negative self-evaluations and reflect low self-worth.

The eudaimonic model extends the hedonic model in one particularly important way. Unlike in hedonic models of well-being, emotions that serve eudaimonic purposes are thought to foster well-being irrespective of their valence [30, 31]. Hence, positive emotions directed at oneself or the patient will likely be important to well-being not merely because they are positive, but also because they reflect fulfilment of basic needs. In contrast, positive emotions directed at an object or situation (e.g., treatment, disease) may be less important and play little role in enhancing well-being, even though they are positive. Moreover, if they reflect bonding with the patient, negative emotions directed at the patient could be favourable to well-being, despite their felt unpleasantness.

To verify these assumptions, we aimed to assess whether positive self-directed emotions (self-worth emotions), positive patient-directed emotions (positive bonding emotions), and certain negative patient-directed emotions (i.e., fear or sadness for the patient; negative bonding emotions) are positively related to well-being in health-care providers. By contrast, we did not expect positive object-directed emotions to be strong predictors of well-being.

Methods

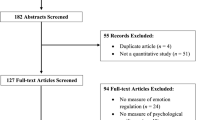

Since no previous study has investigated the different kinds of emotions that arise during patient-provider interactions, there was no suitable instrument to assess emotions within this setting. Therefore, data collection consisted of two steps. First, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews with health-care providers, asking them to report on emotions they experience during distressing interactions with their patients. We documented their (positive and negative) emotions directed at the self, the patient, or an object/situation. Second, directly after the interview, providers completed questionnaires to assess their well-being. Finally, we tested whether the positive self-directed emotions, positive patient-directed emotions, negative patient-directed, and positive object-directed emotions were related to well-being as predicted.

Participants

A convenience sample of 58 health-care providers from the German-speaking part of Switzerland were recruited from hospitals, private practices, and home-care services. Sample characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Measures

Emotions

Emotions were assessed using in-depth interviews. Interviews focused on recent interactions with patients that providers had perceived as distressing, because distressing interactions carry the potential for bringing both positive and negative well-being outcomes for the provider, and are the ones that have repeatedly been indicated to play a crucial role in provider well-being and burnout [29]. Most of the recalled interactions were distressing either because they involved patients who were severely ill (e.g., in palliative care) or difficult to treat for some other reason (e.g., certain personality traits). Most of the interactions selected by interviewees had occured during the previous month, with few having happened between one and several months (but less than a year) ago.

Interviews were conducted by SW (psychologist) and NK (psychology student trained by SW). Together with the interviewer, interviewees explored their emotions and emotion regulation (reported elsewhere) with regard to this interaction. To this end, a manual, which we had developed for this study, was used (see Additional file 1). Specifically, interviewees were asked the following main open-ended question: “Which emotions did you experience while interacting with the patient?” Interviewees’ responses were followed up by more specific questions asking for the provider-perceived directedness of each emotion (e.g., self-, patient-, and object/situation-directed [29]; some emotions were directed at other persons present during the interaction, which was outside the scope of the present study). Each emotion together with its directedness as stated by the interviewee was collected in an interview protocol sheet (see Additional file 1).

For each kind of directedness (self, patient, object/situation) separately, the emotions collected during the interviews were categorised using the classification developed by Shaver and colleagues [44]. This classification categorises various examples of emotions into the higher order categories affection and joy (positive emotions), and anger, sadness, and fear (negative emotions). SW and NK assigned the emotions from the interviewees to the higher order category that included the same or matching examples of emotions. The resulting categorisation of emotions was reviewed by US, BP, and MP, and is displayed in Table 2. A description of providers’ emotions can be found in the results section.

For the statistical analysis of the relationship between well-being and emotions serving eudaimonic purposes, we defined the categories of emotions that serve eudaimonic purposes, i.e., positive self-directed emotions, positive patient-directed emotions, and negative patient-directed emotions that reflect bonding (see Table 3). Henceforth, we call these emotions eudaimonic emotions.

Not all interviewees had reported emotions from all types of eudaimonic emotions listed in Table 3. Therefore, we decided to divide our sample into two subsamples for each type of eudaimonic emotions: In each case, the first subsample comprised interviewees who had not experienced the type of eudaimonic emotions in question (e.g., interviewees who did not experience self-directed positive emotions), the second subsample contained interviewees having experienced these emotions (e.g., interviewees who did experience self-directed positive emotions).

Well-being

After the interview, providers completed pen-and-paper questionnaires to retrospectively assess their state well-being directly after the interaction they had selected. We measured eudaimonic well-being using the validated German version of the 8-item Flourishing Scale (FS; 7-point Likert scale, 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”), which includes items assessing meaning in life, positive relations, mastery, and related concepts [45, 46]. In addition, we measured hedonic well-being using the validated German version of the subjective well-being scales from the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT; 5-point Likert scale, 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”) [47, 48]. These scales assess positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Following usual practice, ratings on FS items were summed together to yield a total score, and ratings on CIT items were averaged to yield mean scores (with higher scores indicating higher well-being in both cases). When responding to the well-being items, providers were asked to retrospectively rate their state immediately after the interaction they had selected for the interview. Items of the CIT had to be slightly adapted (i.e., “most of the time” in six items was dropped) for present purposes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were run using R, Version 3.5.3. We compared the hedonic and eudaimonic well-being scores between providers who had (group 2) and who had not (group 1) experienced eudaimonic emotions for each subdivision (self-directed positive emotions, patient-directed positive emotions, patient-directed negative emotions) separately. Furthermore, since we argued that object-directed positive emotions play little role in enhancing well-being, we compared the hedonic and eudaimonic well-being scores for providers who had (group 2) and had not (group 1) experienced positive object-directed emotions. Because well-being was not normally distributed, we used a Mann-Whitney U test to compare the groups.

Results

Description of emotions in provider-patient interactions

Table 2 depicts all self-, patient-, and object/situation-directed emotions sorted according to the emotion categories by Shaver and colleagues [44]. The most frequently reported self-directed emotions belonged to the category of nervousness (e.g., fear of failure), but providers also reported being confident in themselves and experiencing contentment about their performance. Among the most frequently reported emotions directed at the patient were emotions of affection for the patient (e.g., liking), anger about the patient (e.g., annoyance), and sadness (i.e., sympathy). Regarding object/situation-directed emotions, nervousness (e.g., tenseness about how a situation would develop), relief (e.g., when a problem was resolved), and sadness (e.g., powerlessness in the face of a disease) were most frequently experienced.

Relationship between eudaimonic emotions and well-being

Table 4 depicts results from the group comparisons. Interviewees who had experienced self-directed positive emotions reported a higher eudaimonic (U = 215.00, p = .007, r = .43) and hedonic well-being (U = 237.00, p = .019, r = .38) than those who had not. Patient-directed positive emotions were only related to hedonic well-being (U = 279.50, p = .033, r = .33). There was no difference in well-being between providers with and without object/situation-directed positive emotions. Furthermore, having experienced negative patient-directed emotions that reflect bonding was associated with both higher eudaimonic (U = 216.00, p = .003, r = .46) and hedonic well-being (U = 239.00, p = .009, r = .41).

Discussion

In the present study, we set out to identify emotions in health-care interactions that are linked to health-care provider well-being. The widely used hedonic model of well-being postulates that positive emotions are positively associated with well-being and negative emotions negatively so. We found evidence for a more fine-grained understanding of these associations in health-care providers. Rather than positive emotions in general, only positive emotions directed towards the self or the patient seem to be implicated in well-being. Moreover, for the first time, we found evidence that negative patient-directed emotions such as grieving for the patient were positively associated with well-being in distressing interactions. These findings are consistent with our assumptions based on eudaimonic models of well-being [32, 34,35,36], and may point towards the importance of “eudaimonic” emotions. In other words, emotions such as contentment with oneself, joy for the patient’s improvement, and, notably, grief or worry for the patient are related to well-being, arguably because they build a sense of self-worth and strengthen bonding with the patient.

Importantly, these eudaimonic emotions were not only associated with eudaimonic well-being but also with hedonic well-being. This is not surprising given the fact that eudaimonic and hedonic well-being are related to and mutually reinforce one another [35, 36]. Hence, eudaimonic emotions may directly contribute to hedonic well-being or indirectly contribute to hedonic well-being as a consequence of their direct effects on eudaimonic well-being (or both). Moreover, our findings suggest that in health-care providers, even hedonic well-being might not merely be the product of positive emotions, but also other processes (e.g., eudaimonic ones). This is specifically indicated by the absence of any relation between hedonic well-being and positive object/situation-directed emotions and the positive relation between hedonic well-being and negative bonding emotions.

More generally, an important implication of this study is that eudaimonic models may be better suited to identify emotions that are linked to provider well-being than purely hedonic models. Furthermore, it should be highlighted that negative bonding emotions may in fact be beneficial for providers. This finding stands in contrast with literature on empathy-related processes, where sharing suffering with patients is generally considered to be harmful [49, 50]. More research is needed to elucidate the role of negative bonding emotions. For example, there might be an intensity level where bonding emotions turn harmful. Moreover, Tamir and colleagues highlighted the importance of experiencing contextually useful or desired emotions [30, 51]. Hence, in contexts where empathy could disrupt clinical objectivity and performance, it may not be favourable to well-being [49, 52,53,54]. Consistent with this notion, Decety and colleagues were able to show that physicians downregulate their pain when watching images with body parts in painful conditions [55]. The authors suggest that downregulation is necessary to be able to perform painful medical procedures. Finally, personality traits may play an important role when determining the effects of bonding emotions. Indeed, Tamir and colleagues [30, 31] and Tsai [56] pointed out that only emotional states congruent with an individual’s motives and characteristics are related to well-being. Consequently, bonding emotions might only be relevant for providers who value close relationships with their patients.

There are several limitations to the design of the present study. First, results may be affected by recall bias. Evidence demonstrates that memory of emotional episodes is strongly affected by the overall strongest emotion and emotions experienced at the end of a specific episode (see peak-and-end rule [57]). However, this is not necessarily a limitation, because those emotions lingering on for some time might, in our opinion, be more important to well-being than what providers feel at any given moment. Moreover, due to the large time gap, emotions and the subsequent evaluation of one’s well-being may to some extent have been retrospectively constructed, which could involve reappraisal processes of the situation based on later encounters with the same patient or other experiences. Also, emotions are subject to many influences, including the effects of emotion regulation. Hence, the reported emotions may not be the unadulterated emotions that were originally felt in the given situation. Taken together, our findings may be more representative of providers’ beliefs about emotions and their relationship to well-being than of actual emotional processes. Therefore, results must be replicated by using more real-time emotion assessments [58].

Second, recruiting a convenience sample may have introduced a selection bias because providers interested in participating in this study may differ from those who were not. Moreover, due to the small sample size, there was not enough power to test for differences in results with regards to demographic factors (e.g., profession). For the same reason, we were unable to include variables such as personality traits or work characteristics that may have influenced our findings.

Third, the cross-sectional study design prevents from exploring causal and within-person relationships. Clearly, experimental or prospective studies replicating our findings are needed.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to use a eudaimonic model to understand the relationship between emotions in provider-patient interactions and provider well-being. Findings indicate that experiencing eudaimonic emotions rather than merely enhancing positive emotions and reducing negative ones may be key to well-being. Therefore, this study presents a promising basis for future studies on eudaimonic emotions in particular and on the benefits and costs of health-care interactions in general. By informing education and practice, research along this line may raise awareness of favorable emotional states, stimulate interventions, and ultimately facilitate provider well-being. As provider well-being and good, empathetic patient-provider relationships are associated with quality of care and various patient benefits (e.g. higher treatment adherence) [1, 4, 13, 24, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], experiencing optimal emotional states may translate into improved patient well-being and, ultimately, to more effective health-care systems.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the participants not having consented to the publishing of their data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CIT:

-

Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving

- FS:

-

Flourishing Scale

References

Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L, Mijovic-Kondejewski J, Smith-MacDonald L. Compassion fatigue: a meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003.

Chuang C-H, Tseng P-C, Lin C-Y, Lin K-H, Chen Y-Y. Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(50):e5629.

Rothenberger DA. Physician burnout and well-being: a systematic review and framework for action. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(6):567–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000844.

Simionato GK, Simpson S. Personal risk factors associated with burnout among psychotherapists: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(9):1431–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22615.

Wentzel D, Brysiewicz P. The consequence of caring too much: compassion fatigue and the trauma nurse. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(1):95–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2013.10.009.

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004.

Derksen F, Bensing J, Kuiper S, van Meerendonk M, Lagro-Janssen A. Empathy: what does it mean for GPs? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2015;32(1):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmu080.

Edelkott N, Engstrom DW, Hernandez-Wolfe P, Gangsei D. Vicarious resilience: complexities and variations. Am J Orthop. 2016;86(6):713–24.

Hernandez-Wolfe P, Killian K, Engstrom D, Gangsei D. Vicarious resilience, vicarious trauma, and awareness of equity in trauma work. J Humanist Psychol. 2015;55(2):153–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167814534322.

Kasman DL, Fryer-Edwards K, Iii CHB. Educating for professionalism: trainees’ emotional experiences on IM and pediatrics inpatient wards. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):12.

Råbu M, Moltu C, Binder P-E, McLeod J. How does practicing psychotherapy affect the personal life of the therapist? A qualitative inquiry of senior therapists’ experiences. Psychother Res. 2016;26(6):737–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1065354.

Sacco TL, Copel LC. Compassion satisfaction: a concept analysis in nursing. Nurs Forum (Auckl). 2018;53(1):76–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12213.

Brown R, Dunn S, Byrnes K, Morris R, Heinrich P, Shaw J. Doctors’ stress responses and poor communication performance in simulated bad-news consultations. Commun Ski. 2009;84(11):8.

Canfield J. Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: a review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work. 2005;75(2):81–101. https://doi.org/10.1300/J497v75n02_06.

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15392-5.

Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry J Treat Eval. 2005;2(1):13–20.

Ludick M, Figley CR. Toward a mechanism for secondary trauma induction and reduction: reimagining a theory of secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology. 2017;23(1):112–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000096.

Hensel JM, Ruiz C, Finney C, Dewa CS. Meta-analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims: secondary traumatic stress risk factors. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(2):83–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21998.

Shaw J, Brown R, Heinrich P, Dunn S. Doctors’ experience of stress during simulated bad news consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):203–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.009.

Shaw J, Brown R, Dunn S. The impact of delivery style on doctors’ experience of stress during simulated bad news consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1255–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.023.

Gleichgerrcht E, Decety J. Empathy in clinical practice: how individual dispositions, gender, and experience moderate empathic concern, burnout, and emotional distress in physicians. Zalla T, editor. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61526.

Radey M, Figley CR. The social psychology of compassion. Clin Soc Work J. 2007;35(3):207–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0087-3.

Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ, Chochinov HM, Hack TF, Hagen NA, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0.

Figley CR. The empathic response in clinical practice: antecedents and consequences. In: Decety J, editor. Empathy: The MIT Press; 2011. p. 262–73. [cited 2020 Jan 2]. Available from: http://mitpress.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7551/mitpress/9780262016612.001.0001/upso-9780262016612-chapter-15.

Watson D. Positive affectivity. The disposition to experience pleasurable emotional states. In: Snyder C, Lopez S, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 106–19.

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective Weil-being: three decades of Progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness Lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Weilenmann S, Schnyder U, Parkinson B, Corda C, von Känel R, Pfaltz MC. Emotion transfer, emotion regulation, and empathy-related processes in physician-patient interactions and their association with physician well-being: a theoretical model. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:389. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00389.

Tamir M, Schwartz SH, Oishi S, Kim MY. The secret to happiness: feeling good or feeling right? J Exp Psychol Gen. 2017;146(10):1448–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000303.

Tamir M. Why do people regulate their emotions? A taxonomy of motives in emotion regulation. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2016;20(3):199–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315586325.

Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263.

Seligman MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. 1st Free Press hardcover ed. New York: Free Press; 2011. 349.

Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62(2):95–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and Eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):141–66. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Grawe K. Neuropsychotherapie. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2004. p. 509.

Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM. On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J Psychother Integr. 2013;23(3):263–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359.

Fischer AH, Manstead ASR. Social functions of emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. p. 456–68.

Kaplan HB. Self theory and emotions. In: Stets JE, Turner JH, editors. Handbook of the sociology of emotions, Handbooks of sociology and social research[cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from. Boston: Springer US; 2006. p. 224–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30715-2_11.

Tangney JP, Tracy JL. Self-conscious emotions. In: Leary M, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of self and identity. 2nd ed. New York, London: Guilford Press; 2014.

Weiner B. Judgments of responsibility: a foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. p. 301.

Shaver P, Schwartz J, Kirson D, O’Connor C. Emotion knowledge: further exploration of a prototype approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(6):1061–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061.

Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Esch T, Jose G, Gimpel C, von Scheidt C, Michalsen A. Die flourishing scale (FS) von Diener et al. liegt jetzt in einer autorisierten deutschen Fassung (FS-D) vor: Einsatz bei einer mind-body-medizinischen Fragestellung. Forsch Komplementärmedizin Res Complement Med. 2013;20(4):267–75. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354414.

Su R, Tay L, Diener E. The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT): comprehensive and brief inventory of thriving. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2014;6(3):251–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12027.

Hausler M, Huber A, Strecker C, Brenner M, Höge T, Höfer S. Validierung eines Fragebogens zur umfassenden Operationalisierung von Wohlbefinden: die deutsche version des comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) und die Kurzversion brief inventory of thriving (BIT). Diagnostica. 2017;63(3):219–28. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000174.

Kerasidou A, Horn R. Making space for empathy: supporting doctors in the emotional labour of clinical care. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0091-7.

Austen L. Increasing emotional support for healthcare workers can rebalance clinical detachment and empathy. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(648):376–7. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685957.

Tamir M, Ford BQ. Should people pursue feelings that feel good or feelings that do good? Emotional preferences and well-being. Emotion. 2012;12(5):1061–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027223.

Nightingale SD, Yarnold PR, Greenberg MS. Sympathy, empathy, and physician resource utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(5):420–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02598163.

Meier DE. The inner life of physicians and Care of the Seriously ill. JAMA. 2001;286(23):3007–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.23.3007.

Shanafelt TD, Adjei A, Meyskens FL. When your favorite patient relapses: physician grief and well-being in the practice of oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(13):2616–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.06.075.

Decety J, Yang C-Y, Cheng Y. Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: an event-related brain potential study. Neuro Image. 2010;50(4):1676–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.025.

Tsai JL. Ideal affect in daily life: implications for affective experience, health, and social behavior. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;17:118–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.004.

Fredrickson BL. Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: the importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognit Emot. 2000;14(4):577–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402808.

Simons G, Parkinson B. Time-dependent observational and diary methodologies and their use in studies of social referencing and interpersonal emotion regulation. Twenty-First Century Soc. 2009;4(2):175–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450140903000282.

Firth-Cozens J. Interventions to improve physicians’ well-being and patient care. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(2):215–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00221-5.

Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, Zhou A, Panagopoulou E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

Scheepers RA, Boerebach BCM, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. A systematic review of the impact of physicians’ occupational well-being on the quality of patient care. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(6):683–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3.

Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00117-7.

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0.

Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;8 [cited 2020 Jan 2]. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457/abstract.

Elliott R, Bohart AC, Watson JC, Greenberg LS. Empathy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):43–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022187.

Moyers TB, Miller WR. Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(3):878–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030274.

Nienhuis JB, Owen J, Valentine JC, Winkeljohn Black S, Halford TC, Parazak SE, et al. Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Res. 2018;28(4):593–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1204023.

Blasi ZD, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001;357(9258):757–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04169-6.

Neumann M, Scheffer C, Tauschel D, Lutz G, Wirtz M, Edelhäuser F. Physician empathy: definition, outcome-relevance and its measurement in patient care and medical education. GMS Z Für Med Ausbild. 2012;29(1):Doc11.

64th WMA General Assembly. WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects; 2013. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the interviewees for taking the time to participate in in-depth interviews and for their willingness to share their emotions with the interviewer.

Funding

The study was funded by the Stiftung zur Förderung von Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, which covered participants’ reimbursements and salaries of the interviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW developed the research question and design of the study, conducted and coded interviews, performed data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. MP and US contributed to designing and running the study. NK conducted and coded interviews and both NK and FB helped to prepare data for analyses. CC coded interviews and contributed to the development of the research question. MP, US, TS, BP and RvK provided substantial input on all stages. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As confirmed by the cantonal ethics committee of Zurich (Switzerland), this study did not fall within the scope of the Human Research Act. Therefore, an authorisation from the ethics committee was not required. Nevertheless, this study was carried out in accordance with the Swiss Human Research Ordinance (i.e., under strict confidentiality and privacy, with coding of health-related personal data). All interviewees received written and oral information on the nature, purpose and procedure of the project, their right to withhold or revoke their consent at any time, and their right to receive information. All interviewees gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [70].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Weilenmann, S., Schnyder, U., Keller, N. et al. Self-worth and bonding emotions are related to well-being in health-care providers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 21, 290 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02731-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02731-7