Abstract

Background

One in 2 people born in the UK after 1960 are expected to require oncology input in their lifetime. However, only 36% of UK medical schools provide dedicated oncology placements and teaching indicating a discordance between public health impact and training. We designed a UK-wide survey to capture medical students’ views on current oncology teaching and the potential role of a national undergraduate oncology symposium as an educational, networking and motivational tool.

Methods

We undertook a national cross-sectional survey of UK medical students’ views in oncology and satisfaction with teaching using pre-designed questionnaires. We also distributed a dedicated survey (pre and post-conference) to compare medical students’ motivation towards a career in oncology after attending the national symposium. This study was prospectively approved by QMUL Ethics Committee (Reference number QMREC2348). Statistical analysis included univariate inferential tests on SPSS and GraphPad software.

Results

The national survey was completed by 166 students representing 22 UK medical schools. Students reported limited interest, knowledge and exposure to oncology, lack of confidence in skills, and teaching dissatisfaction. Oncology was perceived as a challenging specialty (mean 4.5/5 ± 0.7), yet most students estimate receiving only 1–2 weeks of dedicated oncology teaching. The national symposium generated a statically significant increase in students’ interest, knowledge, and confidence in skills surrounding oncology, improving students’ perceived ability to cope with the emotional challenges in this field.

Conclusion

Students’ views towards oncology alongside their teaching dissatisfaction underpin the need to revisit and strive to improve current undergraduate oncology curricula. Increasing medical student oncology exposure by proposing outcome-based guidelines and adopting a standardised undergraduate oncology curriculum should be the foremost priority in inspiring future oncologists to ensure excellent cancer patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights of this study

-

To our knowledge, this is the first national cross-sectional survey of UK medical students’ views in oncology.

-

Data collection from the national survey represented several institutions throughout the UK providing valuable insight into students’ views, capturing various different angles.

-

Our described intervention (the National Undergraduate Oncology Conference) was successful in increasing medical students’ interest, knowledge, and confidence in skills towards oncology.

-

Future work should focus on generating outcome-based guidelines to reform undergraduate oncology teaching curricula within medical schools in order to inspire future oncologists and meet increasing societal cancer care demands.

Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide pertaining an imminent global health threat. Latest estimates suggest a 1 in 2 lifetime risk of developing cancer in those born in the UK after 1960 [1]. According to The Edinburgh Declaration of the World Conference on Medical Education, medical education should “reflect the needs of the defined society in which it is situated” [2]. All practitioners will inevitably treat cancer patients as incidences rise [3, 4]. Thus, exposure to oncology is fundamental regardless of specialisation. Most general health of cancer patients is managed by non-cancer-specialists including newly-qualified doctors and primary care physicians with limited or no postgraduate oncology training [4,5,6].

Despite rising global cancer burden and an increasing global demand for oncologists to join the workforce [7, 8], several studies report ongoing underrepresentation and lack of consistent undergraduate oncology teaching [9,10,11,12,13,14] with few universities offering dedicated oncology teaching blocks [15,16,17]. As far as we know, UK medical schools rarely distinguish between medical, clinical/radiation, and surgical oncology teaching within undergraduate curricula as these are often discussed collectively in the context of specific diseases. Oncologists are concerned about medical students’ cancer-related skills and knowledge, especially considering its fragmented teaching across systems leading to factual omissions [14, 18, 19]. Although several extra-curriculum teaching programmes, including conferences and extended week courses, run across several European countries and overseas [20,21,22,23], there is still an evident need to reform undergraduate oncology teaching curricula to meet societal and clinical practice needs [24,25,26].

Therefore, the aims of this study were to (1) survey national medical student views on oncology including their knowledge, confidence in skills, and satisfaction with oncology teaching in undergraduate medical education and (2) evaluate the impact of a national undergraduate oncology conference on students’ views on oncology.

Methods

Our evaluation included a national cross-sectional mixed survey seeking Likert scale, multiple choice, binary yes/no, and free text responses. We also performed a comparative targeted-group pre and post-conference quasi-experimental survey seeking similar responses.

Participants

National survey

Medical students attending any of the 41 recognised UK medical schools were invited to complete an electronic questionnaire disseminated during March–May 2020, advertised in two cycles. The survey was distributed via the Medical Schools Council (MSC) to UK medical school staff who then disseminated the survey to student cohorts. The survey was also promoted via student association channels, including newsletter and social media.

Pre/post-conference questionnaires

Medical students attending the National Undergraduate Oncology Conference, London, 7th March, 2020, were invited to complete two questionnaires each distributed via email using three reminder rounds for each, 1 week before and after the conference respectively. The pre-conference questionnaire was also available electronically and in paper format at conference registration.

Intervention

Questionnaires

Questionnaires were designed according to a literature search of oncology questionnaires aimed at medical students. Discussions between research team members contributed to the final questionnaire components and design. The national survey assessed students' views towards oncology in five domains including: career interest, emotional attitudes, knowledge or exposure, confidence in skills, and teaching satisfaction. The national survey and pre-conference questionnaire (Appendix 1 and 2 respectively) contained identical questions; the post-conference questionnaire (Appendix 3) contained an extra section dedicated to feedback. Excluding questions pertaining to participant demographics, each questionnaire compromised 34 questions sub-divided into views on oncology, and views on oncology teaching, including 32 questions on a 5-point Likert scale, one multiple choice, and one free text response.

Conference

The National Undergraduate Oncology Conference was designed as a supplementary educational tool by lecture-based format. Smaller group-based workshops encouraged networking and allowed for exchange of ideas between students, but also with clinicians and patients. A CV-building workshop served as a signpost for career avenues within hospital-based and academic oncology.

Comparisons

We assessed responses across geographical location, medical school, age, and student year groups. We also assessed motivation improvement and perception of knowledge pre and post-conference. We finally compared motivation towards oncology between students who attended the conference (pre and post-conference) versus the national average.

Outcomes

National Survey

We assessed students’ views towards oncology as measured by Likert scale responses concerning their interest, knowledge and exposure, and teaching satisfaction.

Conference feedback questionnaire

The effectiveness of the conference as an educational, networking and motivational tool was measured by assessing for a significant change (p < 0.05) in students’ pre and post-conference responses.

Ethical approval

All surveys were prospectively approved by the Queen Mary University of London Ethics Committee (Reference number QMREC2348). All participants consenting to anonymous data being used for this study and/ or additional data analysis and publication via a peer-reviewed journal.

Procedures to minimise bias

Questionnaires were piloted in a small group of medical students before being reviewed and launched to ensure questions were unambiguous and phrasing did not generate responder bias. Informed consent statements were included at the beginning of each survey. The national survey gathered completely anonymous data, hence, participants were informed of their right to withdraw only prior to survey submission as data could not be selected for exclusion thereafter. Conversely, in the pre and post-conference surveys, participants provided an anonymised identifier (ID) that allowed for matching of individual participant data to enable comparison of results and view changes in perception. Conference participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time even after survey submission as responses could be selected for exclusion by quoting the anonymised ID.

Data collection

All surveys were conducted via a standardised, web-based, data collection form (Google Form, Google, Alphabet Inc.). Responses were saved to a password-protected Excel file. Data was cleaned and matched by S.H. and K.R. for ease of statistical analysis. Regarding free text responses (qualitative data) S.H. and K.R. proceeded to a pilot thematic analysis; this resulted in discrete thematic axes. Those thematic axes were revised by N.S. to ensure accuracy of data; any discrepancy was resolved through discussion with the senior author of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed on IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows Version 26 and GraphPad Prism 8 software. SPSS descriptive statistics were used to analyse student demographics, views on undergraduate oncology teaching, and conference feedback. Following assessment of data distribution, we used Mann-Whitney U (MWU) test for different group comparisons and Wilcoxon signed-rank (WSR) test for paired association. P-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and the Corrected Item-total Correlations (ICC) assessed the internal consistency reliability of national survey data. Cronbach’s Alpha between 0.5 and 0.7 was considered to reflect an acceptable internal consistency while > 0.7 was good. The ICC determined the level of agreement between measurements. ICC < 0.2 was regarded as poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 as fair, 0.61–0.80 as good, and 0.81–1.0 as very good [25].

Results

Demographics

National survey

In total, 166 medical students completed the national survey. The median age of responders was 22 (IQR = 3). The majority (82%) studied on an undergraduate course while the remainder either studied on a graduate entry programme (GEP), which is an accelerated medical programme for students with a previous degree, or were taking a year out of their medical course to intercalate in another field of study obtaining an additional degree. Responders included students of all year groups, representing 22 different UK medical schools. Participant demographics are summarised in Table 1.

Conference

Sixty-two students attended the conference, out of which 58 (93.5%) completed the pre-conference questionnaire and 41 (66.1%) completed the post-conference questionnaire. Comparative statistics were performed on 34 (54.8%) medical students for whom pre and post-conference data was available. Of these 34, the median age was 21 (IQR = 1.5) (Table 1).

Students’ views on oncology

Table 2 describes students’ views towards oncology compared to those attending the conference (prior and after). In a nutshell, nationally, most students report being unlikely or unsure towards pursuing a career in oncology (mean score: 2.7 ± 1.1) prior to entering medical school, and neutral interest at the time of the conference (mean score: 3.1 ± 1.2) (Table 2). Overall, students perceive oncology as a challenging specialty (mean score: 4.5 ± 0.7) and report minimal exposure during their undergraduate training (mean score: 1.9 ± 1.0) (Table 2).

Comparison to conference delegates’ views

Conference attendees reported a statistically significant higher likelihood of pursuing a career in oncology compared to national responders (3.1 vs. 2.7/5, p = 0.0322, Table 2), however, overall most questionnaire items had similar responses. Noteworthily, delegates did not consider oncology to be as challenging (4.1 vs. 4.5/5, p = 0.0171), as well as expressed less pessimism towards cancer (2.3 vs. 2.7/5, p = 0.0232). Additionally, delegates reported higher exposure to oncology training pathways (2.5 vs. 1.9/5, p = 0.0070), the cancer patient pathway (3.4 vs. 2.8/5, p = 0.0201), cancer research (2.7 vs. 2.1/5, p = 0.0052), and more confidence in building their CVs towards a career in oncology (2.3 vs. 1.8/5, p < 0.0001).

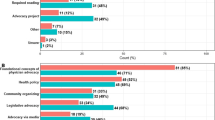

Satisfaction with undergraduate oncology teaching

Nationally, students reported poor satisfaction with pre-clinical and clinical oncology teaching (mean score: 2.8 ± 1.1, Table 3). Most students estimated they would receive between 1 and 2 weeks (21.7%) or 3–4 weeks (15.7%) of dedicated oncology teaching throughout their degree (Supplementary Table 1); median 3–4 weeks.

Delegates reported similar teaching satisfaction ratings to national survey responders, yet pre-clinical teaching satisfaction was statistically significantly higher (Table 3). Conference attendees also reported more dedicated oncology teaching hours, reporting 4–6 weeks (14.7%) or 6–8 weeks (14.7%) of teaching (Supplementary Table 1); median 4–6 weeks.

Impact of oncology conference

Table 4 represents the impact of the oncology conference on students’ views.

Generating interest in oncology and shaping students’ views

Following the symposium, students reported a statistically significant increase in overall likelihood of pursuing a career in oncology (3.9 vs. 3.1/5, p = 0.0012) and improved ability to cope with the emotional challenges associated with a career in oncology (3.8 vs. 3.3/5, p = 0.0278) which the conference aimed to address through the patient panel and patient interaction workshop.

Value of conference as an educational tool

Post-conference, students felt a significant improvement in their knowledge and confidence concerning all aspects discussed during the lectures and workshops (Table 4).

Internal consistency reliability analysis

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient based on standardised items was 0.849 (Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient = 0.849) demonstrating good internal consistency of the survey data. The mean ICC was 0.226 indicating fair agreement between measurements.

Discussion

National findings

The national survey aimed to determine medical students’ views on oncology including their knowledge, confidence in skills, and teaching satisfaction to identify areas of improvement in undergraduate education. Lack of interest and insufficient exposure to oncology including the specialty training pathway was identified. Oncology was rated as a challenging specialty, and students reported poor confidence in oncology skills especially in regard to building their CV towards a career in oncology; understanding clinical trial research; communicating about death with patients; identifying skin cancers; and understanding the role of interventional radiology in cancer treatment (Table 2). Students were unsatisfied with oncology teaching. Findings are consistent worldwide, with students reporting limited oncology specialty exposure [9, 27]; teaching dissatisfaction [28]; and poor confidence in oncology care [9, 29, 30]. Newly-qualified doctors report limited undergraduate exposure to cancer patients, and lack of cancer care knowledge [6, 31]. Furthermore, although recommendations for undergraduate oncology teaching indicate at least 2 weeks of dedicated teaching, [32, 33] with 2–3-weeks full-time towards the end of undergraduate years, [14] most national survey responders (20.7%) estimated receiving only 1–2 weeks of teaching. A third of students (33.1%) were unable to estimate the number of teaching weeks raising questions about whether these students receive any dedicated oncology teaching at all. This corroborates with other research, suggesting only 61% of first-year trainee doctors receive any oncology placement at medical school, [6] while 36% of UK medical schools offer dedicated oncology placements [10].

Conference findings

We hypothesised that the conference may be a valuable educational tool. Delegates’ inclination towards oncology career pathways was further increased post-conference. The event successfully increased students’ knowledge and exposure to oncology including the specialty training and patient pathways. The educational utility of the conference is demonstrated by delegates’ dramatically improved confidence in skills, especially in identifying skin cancer lesions. Indeed, extracurricular teaching programmes including mentorship schemes, [32,33,34,35] conferences, and dedicated teaching courses [15, 18,19,20,21] are effective in generating student interest while improving knowledge and skills.

Significance of findings

With increasing global demand for oncologists to join the workforce, [7, 8] the importance of early undergraduate oncology teaching cannot be overemphasised. The majority of cancer patient care is performed in specialist centres, hence limited student oncology exposure may be due to restricted placement availability [16]. Nonetheless, placement accessibility is of utmost importance as early specialty exposure increases medical students’ interest [34,35,36]. Thus, lack of student interest in oncology is unsurprising considering their limited exposure.

Recommendations

A targeted educational needs assessment of medical students is essential in devising guidelines for an optimal undergraduate oncology curriculum [37]. Our recommendations are based on students’ feedback in free text responses. Nationally, students advocated for more dedicated clinical exposure to oncology, increased teaching hours, and more diverse coverage of cancer topics. Several students suggested restructuring oncology curricula and more clinical skills teaching covering breaking bad news and communicating with terminally-ill patients. Developing guidelines encompassing core oncology skills-based knowledge outcomes is a priority. Familiarising students with a specialty is an effective strategy to prevent specialty attrition and trainee burn-out. Increasing students’ oncology exposure is a key way to generate interest and motivate students to pursue this specialty in hopes of creating a better future generation of holistically qualified oncologists who are enthusiastic about laboratory and clinical research [38,39,40]. Although securing clinical placements for students at specialist oncologist centres may be difficult to achieve, a lot of cancer patient management is carried out in non-specialist centres including primary care. Hence, encompassing more oncology teaching within general practice placements would be a helpful means to overcome this issue. Being able to break bad news sensitively is relevant for all aspects of medicine and more dedicated communication skills teaching on the subject is essential.

A criticism of undergraduate oncology teaching is that it can at times be pitched to a postgraduate level, thus, contributing to disinterest and confusion amongst students. Medical school teaching should be tailored to preparing students to manage common oncological presentations and emergencies that they will encounter as foundation year doctors, as opposed to specific cancer treatment regimens. The clinical oncology faculty of the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) jointly published the “Undergraduate non-surgical oncology curriculum” in September 2020 [41] in accordance with the latest General Medical Council “Outcomes for graduates 2018”. UK medical schools often have their own curriculum with intended learning outcomes for oncology and these should be continually scrutinised and revised to meet the requirements set out by the RCR and RCP curriculum. Some of the salient outcomes that deserve more emphasis include:

-

“Undertake a focused oncological history focusing on common and ‘red flag’ symptoms”

-

“Undertake a focused oncological examination e.g. assessment for metastatic spinal cord compression”

-

“Describe appropriate urgent referral pathways for patients with a suspected cancer”

-

“Demonstrate communication skills e.g. principles of breaking bad news and shared decision-making with a patient”

-

“Demonstrate a holistic clinical assessment of patients with cancer including the local and systemic sequelae of common cancer presentations”.

Many of these are also echoed by the students’ responses in our surveys.

Strengths

Scarce data is available on medical students’ perspectives on current undergraduate oncology teaching with data almost non-existent for the UK [28, 42,43,44,45,46,47]. To our knowledge, this is the first national cross-sectional survey of UK medical students’ views in oncology. The strengths of this study include its prospective protocol approval, the national representability of findings to several medical schools, and the variety of questionnaire components capturing different angles.

Limitations

National findings

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and lack of questionnaire validation. A sample size of >1000 national responders would have increased robustness of results. Representativeness of findings was limited by only having responses from 22 UK medical schools. Lack of response from certain institutions may be explained by small cohort sizes in these medical schools and ‘survey fatigue’. A large proportion of student responders were in pre-clinical years and will inevitably have been less confident in communicating with cancer patients. These students may not be aware of clinical oncology teaching if this was scheduled to take place in clinical years, hence providing an inaccurate underestimation of the amount of dedicated oncology teaching they receive. Although we captured some data regarding students’ satisfaction with pre-clinical oncology teaching (Table 3), our questionnaires primarily focused on clinical teaching. Pre-clinical oncology teaching is vastly inconsistent between medical schools and is challenging to assess as it is often integrated within pathology, histology and organ systems’ teaching.

Conference findings

With regards to the effectiveness of the conference as an educational tool, the overall increase in students’ self-reported knowledge, exposure, and confidence was not validated by an objective method of assessment. The apparent changes could have been influenced by response acquiescence or acceptance bias which led students to provide a higher estimate of their knowledge in the post-conference questionnaire. Resurveying students after a longer period of time (e.g. 12 months) may eliminate these short-lived artifacts. We could also examine if delegates carried on this confidence into their foundation training posts and compare their average scores with those of foundation doctors who had not attended the event. Lastly, we cannot discount the inherent selection bias as students who chose to attend the conference already had interest towards oncology and an innate inclination towards this specialty. This must be considered when interpreting our findings, especially when conference results are compared or generalised to the national cohort.

Conclusion

In summary, findings herein demonstrate deficiencies in medical students’ knowledge, exposure, and confidence in skills especially in regard to building their CV towards a career in oncology; understanding clinical trial research; communicating about death with patients; identifying skin cancers; and understanding the role of interventional radiology in cancer treatment. Students estimate receiving less than the recommended 2–3 weeks of oncology teaching [14]. Although the undergraduate oncology conference has demonstrated effectiveness as an educational tool, it is still necessary to revisit and strive to improve undergraduate oncology curricula. Developing a high quality uniformly structured, systematic undergraduate oncology curriculum should become a national and international priority; equally, proposed teaching guidelines should be revised and adhered to. Students’ attitudes should be considered when formulating curricula as they provide valuable insight into future doctors’ needs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets/ questionnaires used and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmad AS, Ormiston-Smith N, Sasieni PD. Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. Br J Cancer. 2015 Mar 3;112(5):943–7.

Roddie IC. The Edinburgh declaration. Lancet Lond Engl. 1988;2(8616):908.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australasian Association of Cancer Registries. Cancer in Australia 2000. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare : Australasian Association of Cancer Registries; 2003.

Barton MB, Bell P, Sabesan S, Koczwara B. What should doctors know about cancer? Undergraduate medical education from a societal perspective. Lancet Oncol. 2006 Jul;7(7):596–601.

Ravaud A, Hoerni B, Bécouarn Y, Lagarde P, Soubeyran P, Bonichon F. A survey in general practice about undergraduate cancer education: results from Gironde (France). J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 1991;6(3):153–7.

Cave J, Woolf K, Dacre J, Potts HWW, Jones A. Medical student teaching in the UK: how well are newly qualified doctors prepared for their role caring for patients with cancer in hospital? Br J Cancer. 2007 Aug 20;97(4):472–8.

Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists : challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007 Mar;3(2):79–86.

The Royal College of Radiologists. Clinical oncology UK workforce census 2017 report. London: The Royal College of Radiologists; 2018.

Mattes MD, Patel KR, Burt LM, Hirsch AE. A Nationwide medical student assessment of oncology education. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2016;31(4):679–86.

Payne S, Burke D, Mansi J, Jones A, Norton A, Joffe J, et al. Discordance between cancer prevalence and training: a need for an increase in oncology education. Clin Med. 2013 Feb;13(1):50–6.

Tam VC, Berry S, Hsu T, North S, Neville A, Chan K, et al. Oncology education in Canadian undergraduate and postgraduate medical programs: a survey of educators and learners. Curr Oncol Tor Ont. 2014;21(1):e75–88.

McRae RJ. Oncology education in medical schools: towards an approach that reflects Australia’s health care needs. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2016;31(4):621–5.

Tattersall MH, Langlands AO, Simpson JS, Forbes JF. Undergraduate education about cancer: a survey in Australian medical schools. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24(3):467–71.

Peckham M. A curriculum in oncology for medical students in Europe. Acta Oncol. 1989;28(1):141–7.

Agarwal A, Koottappillil B, Shah B, Ahuja D, Hirsch AE. Medical student--reported outcomes of a radiation oncologist--led preclinical course in oncology: a five-year analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015 Jul 15;92(4):735–9.

Mayes J, Davies S, Harris A, Wray E, Dark GG. Impact of a 2-week oncology placement on medical students’ perception of Cancer. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2018;33(1):174–9.

Granek L, Lazarev I, Birenstock-Cohen S, Geffen DB, Riesenberg K, Ariad S. Early exposure to a clinical oncology course during the preclinical second year of medical school. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2015;90(4):454–7.

Brincker H. Scandinavia. J Cancer Educ. 1988;3(2):97–101.

Gaffan J, Dacre J, Jones A. Educating undergraduate medical students about oncology: a literature review. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr 20;24(12):1932–9.

Pavlidis N, Vermorken JB, Costa A. Oncology for medical students: a new ESO educational avenue. Ann Oncol. 2005 May 1;16(5):840–1.

Pavlidis N, Vermorken JB, Stahel R, Bernier J, Cervantes A, Audisio R, et al. Oncology for medical students:: A European School of Oncology contribution to undergraduate cancer education. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(5):419–26.

Pavlidis N, Gatzemeier W, Popescu R, Stahel R, Pinedo H, Cavalli F, et al. The masterclass of the european school of oncology: the “key educational event” of the school. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl. 2010;46(12):2159–65.

Pavlidis N, Vermorken JB, Stahel R, Bernier J, Cervantes A, Pentheroudakis G, et al. Undergraduate training in oncology: an ESO continuing challenge for medical students. Surg Oncol. 2012 Mar;21(1):15–21.

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010 Dec 4;376(9756):1923–58.

DeNunzio NJ, Hirsch AE. The need for a standard, systematic oncology curriculum for U.S. medical schools. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86(8):921.

Kwan JYY, Nyhof-Young J, Catton P, Giuliani ME. Mapping the Future: Towards Oncology Curriculum Reform in Undergraduate Medical Education at a Canadian Medical School. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(3):669–77.

Dennis KEB, Duncan G. Radiation oncology in undergraduate medical education: a literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Mar 1;76(3):649–55.

George M, Mandaliya H, Prawira A. A survey of medical oncology training in Australian medical schools: pilot study. JMIR Med Educ. 2017;3(2):e23.

Neeley BC, Golden DW, Brower JV, Braunstein SE, Hirsch AE, Mattes MD. Student perspectives on oncology curricula at United States medical schools. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2019;34(1):56–8.

Oskvarek J, Braunstein S, Farnan J, Ferguson MK, Hahn O, Henderson T, et al. Medical student knowledge of oncology and related disciplines: a targeted needs assessment. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2016;31(3):529–32.

Bandyopadhyay A, Das A, Ghosh A, Giri R, Biswas N. Oncology knowledge gap among freshly passed interns in a government medical College of Eastern India. South Asian J Cancer. 2013 Jan 4;2(2):62.

Undergraduate Education in Cancer in the European Region. Report on a UICC/WHO Meeting (Geneva, Switzerland, April 6–8, 1981). Geneva: World Health Organization, Distribution and Sales Service; 1981.

International Union Against Cancer (UICC). Cancer Education for Undergraduate Medical Students: Curricula from around the world. In: Robinson E, Sherman CD, Love RR, editors. Undergraduate Education Around the World by E Robinson. Geneva: UICC; 1994. p. 1–9.

Compton MT, Frank E, Elon L, Carrera J. Changes in U.S. medical students’ specialty interests over the course of medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Jul;23(7):1095–100.

Indyk D, Deen D, Fornari A, Santos MT, Lu W-H, Rucker L. The influence of longitudinal mentoring on medical student selection of primary care residencies. BMC Med Educ. 2011 Jun 2;11(1):27.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010 May 1;29(5):799–805.

DeNunzio NJ, Joseph L, Handal R, Agarwal A, Ahuja D, Hirsch AE. Devising the optimal preclinical oncology curriculum for undergraduate medical students in the United States. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):228–36.

Sideris M, Papalois A, Theodoraki K, Dimitropoulos I, Johnson EO, Georgopoulou E-M, et al. Promoting undergraduate surgical education: current evidence and students’ views on ESMSC international wet lab course. J Investig Surg Off J Acad Surg Res. 2017;30(2):71–7.

Sideris M, Nicolaides M, Theodoulou I, Emin EI, Hanrahan JG, Dedeilia A, et al. Student views on a novel holistic surgical education curriculum (iG4): a multi-national survey in a changing landscape. Vivo Athens Greece. 2020;34(3):1063–9.

Theodoulou I, Sideris M, Lawal K, Nicolaides M, Dedeilia A, Emin EI, et al. Retrospective qualitative study evaluating the application of IG4 curriculum: an adaptable concept for holistic surgical education. BMJ Open. 2020 Feb 9;10(2):e033181.

Undergraduate non-surgical oncology curriculum 2020 | The Royal College of Radiologists [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.rcr.ac.uk/clinical-oncology/careers-and-recruitment/undergraduate-oncology/undergraduate-non-surgical-oncology

Biswal BM, Zakaria A, Baba AA, Ja’afar R. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and exposure to oncology and palliative care in undergraduate medical students. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(1):78–83.

Barton MB, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Crossing S, Jamrozik K, Jalaludin B, et al. Cancer knowledge and skills of interns in Australia and New Zealand in 2001: comparison with 1990, and between course types. Med J Aust. 2003 Mar 17;178(6):285–9.

Soliman AS, Raouf AA, Chamberlain RM. Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and barriers to cancer control and screening among primary care physicians in Egypt: the need for postgraduate medical education. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 1997;12(2):100–7.

Bernard LJ, Carter RA. Surgical oncology education in US and Canadian medical schools. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 1988;3(4):239–42.

Zapka JG, Luckmann R, Sulsky SI, Goins KV, Bigelow C, Mazor K, et al. Cancer control knowledge, attitudes, and perceived skills among medical students. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2000;15(2):73–8.

Estévez RA, de Estévez OT, Cazap EL, Gonzales Montaner LJ, Martinez M, Pinasco H, et al. Undergraduate teaching of oncology in Argentina. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 1988;3(2):111–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.R. has contributed in the conception and design of the work, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. A.W. has contributed in data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. S.H. has contributed in data collection, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. N.S./ B.S. have contributed in the design of the work and final approval of the version to be published. M.N. has contributed in the conception and design of the work and final approval of the version to be published. M.S./ A.P. have contributed in the conception and design of the work, data interpretation, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by Queen Mary Ethics of Research Committee the license reference number is QMREC2348, MS et al. and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was ethically obtained from all participants in the study prior to their participation (Appendix 1, 2, 3).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Appendix 1. National survey.

Additional file 2.

Appendix 2. Pre-conference questionnaire.

Additional file 3.

Appendix 3. Post-conference questionnaire.

Additional file 4.

Appendix 4. Ethical approval.

Additional file 5.

Supplementary Tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rallis, K.S., Wozniak, A.M., Hui, S. et al. Inspiring the future generation of oncologists: a UK-wide study of medical students’ views towards oncology. BMC Med Educ 21, 82 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02506-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02506-0