Abstract

Background

To identify the: extent to which medical students in China experience burnout; factors contributing to this; potential solutions to reduce and prevent burnout in this group; and the extent to which the experiences of Chinese students reflect the international literature.

Methods

Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Key words, synonyms and subject headings were used to search five electronic databases in addition to manual searching of relevant journals. Titles and abstracts of publications between 1st January 1989-31st July 2016 were screened by two reviewers and checked by a third. Full text articles were screened against the eligibility criteria. Data on design, methods and key findings were extracted and synthesised.

Results

Thirty-three studies were eligible and included in the review. Greater levels of burnout were generally identified in males, more senior medical students, and those who already experienced poorer psychological functioning. Few studies explored social or contextual factors influencing burnout, but those that did suggest that factors such as the degree of social support or the living environment surrounding a student may be a determinant of burnout.

Conclusions

Greater understanding of the social and contextual determinants of burnout amongst medical students in China is essential towards identifying solutions to reduce and prevent burnout in this group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Burnout amongst health professionals is characterised by “various degrees of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a low sense of personal accomplishment” [1]. Although the detrimental consequences of burnout on clinician well-being and patient care are widely documented, burnout continues to be endemic in the health system [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Symptoms of burnout are prevalent from the outset of medical training, with multi-institutional studies indicating that at least 50% of medical students may meet burnout criteria at some point during their studies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Burnout in medical school has potential to negatively impact on students’ academic development and overall well-being, with burnout identified as a significant independent predictor of suicide ideation and dropping out of medical school [11]. A number of potential solutions and strategies to prevent and reduce burnout amongst medical students are evidenced in literature, but these largely report data solely from students in English-speaking countries.

Strategies at individual, and structural or organisational strategies have all reported clinically meaningful reductions in burnout amongst doctors [19]. Such strategies include the: promotion of healthier lifestyle choices and social activities in medical training; provision of psychosocial support; web-based interventions; guidance to support positive attribution styles during the teaching process; and elective courses for learning relaxation techniques [20,21,22,23,24]. In the workplace, contextual factors such as working hours, social support and relationships with co-workers have been increasingly recognised as key determinants of burnout and therefore targets for intervention [25]. Yet a recent systematic review highlighted that knowledge regarding the interventions that are most effective for specific populations of medical students is lacking [19].

China has the largest number of medical practitioners in the world, and these practitioners service the world’s biggest population of 1,400,000,000, yet studies that report the experiences of medical students in China are under-represented in the English language literature [26]. As such, there is a dearth of knowledge about the contextual factors that influence burnout in Chinese medical students. It is important to explore this area in order to understand not only the scale of the problem of burnout in Chinese medical students but also to develop possible evidenced-based solutions.

To address this gap, a systematic review of studies of burnout amongst medical students in China in both mainstream and Chinese language research databases, was undertaken. The review had four aims. These were to identify: 1) the extent to which medical students in China are experiencing burnout; 2) the demographic, social and psychological factors contributing to this, 3) potential solutions to reduce and prevent burnout in China and; 4) the extent to which experiences in China reflect the international literature.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement is an evidence-based approach for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The PRISMA statement was used to guide the reporting of this systematic review [27].

A range of text words, synonyms and subject headings were developed for the three major concepts in this review of 1) burnout, 2) the associated constructs of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment, and 3) medical education settings in China. These phrases were combined with AND and used to undertake a systematic search of five electronic databases from January 1989 to July 2016. The date range was selected to identify sufficient relevant literature within a relatively recent timeframe given the changing context of medical education. Databases searched were: MEDLINE, China Academic Journals Full-text Database, Chinese Scientific Journals Database,Wanfang Data Resource System. Hand searching of relevant journals (e.g. Chinese Journal of Medical Education Research and Chna Higher Medical Education) and reference lists of the included papers ensured that relevant published material was captured. Results were merged using reference-management software (Endnote) and duplicates removed.

Several limitations were applied. Only studies with the following.

characteristics were included: available in English or Chinese languages that reported original primary data published from January 1989–July 2016; subjects were medical students of Chinese origin studying in China; any study design (including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research); any study which validated or purpose-developed assessment of burnout or its constructs of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation or personal accomplishment. In studies that included other professions in the sample, only data relating to medical students were extracted for the present review.

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the above criteria. Literature assessing hypothetical vignettes or scenarios rather than actual experience was excluded, in addition to studies that focused on general well-being or psychological well-being but not specifically burnout. Articles that focus on medical teachers, trainees, residents, nurses and nurse students were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts (WC; CB). Copies of full articles were obtained for those that were potentially relevant. Inclusion criteria were then independently applied to the articles by the two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third reviewer. The following data were extracted: author(s), publication year, sample, setting, design, primary focus and main findings.

Data synthesis

Findings were analysed using a narrative synthesis in stages based on the study objectives [28]. A narrative approach was utilised to synthesize the findings as given the heterogeneity of the outcome measures used, whilst many studies used variants of the same measure, these were not consistently used in every study and therefore a narrative synthesis was appropriate on this occasion. A quantitative approach was not considered appropriate as the measures were not directly comparable [28]. Initial descriptions of the eligible studies and results were tabulated (presented in Table 1). Patterns in the data were explored to identify consistent findings in relation to the study objectives. Interrogation of the findings explored relationships between study characteristics and their findings; the findings of different studies; and the influence of the use of different outcome measures, methods and settings on the resulting data.

Data appraisal

All the papers were evaluated using medical education research study quality instrument (MERSQI) [29]. The possible score of MERSQI range 5–18, including study design (1–2), sampling (1–3), type of data (1–3), validity of evaluation instruments’ scores (0–3), data analysis (1–3), outcome (1–3). Two reviewers individually assessed all publications; disagreements were resolved through discussion. Due to the limited number of eligible publications, we did not exclude studies based on the quality assessment; quality assessment data was used simply to portray the strength of the available evidence.

Results

Search results

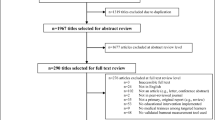

Using the search strategy described above, 380 references were retrieved, including 6 articles from MEDLINE, 157 articles from the China Academic Journals Full-text Database, 99 articles from the Chinese Science Citation Database and 118 articles from Wanfang Data Resource System. Thirty-three studies were included (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

The main characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 1. The range of sample size was between 77 and 1402. There was a total of 14,774 participants across all of the studies. The year of the studies included were from 2008 to 2015. Among 33 studies, seven studies divided participants into two or three groups to compare; 10 studies recruited students from more than two institutions. There were 25 studies analysing the present situation, seven studies were retrospective control studies and only one prospective cohort study (see Table 1). There was no randomized controlled experiment study design among the articles. Seven were non-randomized two group studies while one was a single group pre and post-test design. The remainder were single group cross-sectional or single group post-test only.

Study quality

Among the the 33 included studies, the MERSQI score range was 8–13. The mean total MERSQI score was 11.3. Response rate of all the studies were over 75%. Data analysis of all the articles included were appropriate for study design and type of data. However, the outcome of the articles are mostly satisfaction, attitudes, perceptions, opinions and general facts according to MERSQI. Only two articles developed knowledge or skills as outcome based on the study [30, 31].

Review findings

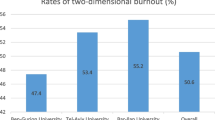

Included studies reported high levels of burnout amongst medical students in China, with over 40% of students in most studies identified as having more than moderate levels of burnout [32,33,34,35,36,37].Among the 33 studies included, only five studies solely targeted graduate medical students, with three further studies that targeted graduate medical students in addition to interns and undergraduate medical students [33, 38,39,40,41,42,43]. The remaining 25 studies targeted undergraduate medical students.

- i.

Demographic factors

Gender, age and whether the student was from an urban or rural setting were all identified as significant predictors in some studies, but findings were not consistent across the included studies. A total of eight studies reported gender as a significant predictor of burnout or its at least one of its constructs, with males experiencing a greater degree of suffering than females [33, 35, 37, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47]. Of the studies identified, two found that scores for emotional exhaustion in males were significantly higher than in females [41, 42]. Another four studies found that males’ scores for depersonalization were also significantly higher than in females [35, 44, 45, 47]. In contrast, Yang et al. (2011), reported significantly lower scores on personal accomplishment in males than in females and two further studies found no significant difference in the total burnout score between males and females [30, 44, 48].

Overall burnout scores among different grades of medical students varied significantly in six studies [30, 36, 45, 46, 48, 49]. All identified that more senior students suffered greater burnout, with third and fourth year students reporting significantly higher scores than first and second year students [30, 36, 45, 46, 48]. Only one study did not report any significant differences between overall burnout scores between different grades of students [47]. Related to this, four studies reported a positive correlation between burnout and the students’ sense of continuing commitment to the medical profession or study pressure experienced [31, 40, 50, 51]. A significant negative correlation between students motivation to accomplish and burnout was reported in two further studies, although a third found no such association [52,53,54].

The extent of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization among medical students significantly increased with age in one study [55]. Whilst a second study identified that the level of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation significantly increased with age, no significant difference in the overall burnout score was identified between different age groups [39].

A statistically significant difference was identified in one study in the overall burnout scores of medical students from different areas (village, town and city); students who came from a village had higher learning burnout scores than students who came from a city or township [30]. An additional study reported that whilst there was no significant difference in overall burnout scores of medical students from rural or urban settings, medical students from rural areas had a significantly lower score than those from cities in the dimension of personal accomplishment [41]. Another two studies reported no significant difference in overall burnout scores or any dimension of burnout between those in different areas. [33, 45]

- ii.

Social factors

A total of three studies explored the association between social support and burnout using the Social Support Rate Scale (SSRS) [35, 39, 42]. Two of these studies found that the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions of burnout among medical students were significantly negatively correlated with social subjective support and the utilisation level of social support [39, 42]. The third study found that all the three dimensions of burnout were significantly negatively correlated with social subjective support such as family, friends and organisation [35]. Social support and self-efficacy were identified as negatively associated with burnout in two further studies [47, 56]. One of these explored social support in terms of the interpersonal relationships and learning atmosphere in dormitories in which medical students lived [47]. The results showed that interpersonal relationships and learning atmosphere were negatively correlated with dimensions of burnout (exhaustion and depersonalisation), which meant that the better interpersonal relationships within the dormitories was able to reduce the burnout rate.

- iii.

Psychological factors

Of the studies identified, three reported associations between burnout and other psychological constructs, indicating that those experiencing poorer mental health overall were also more likely to suffer burnout [30, 32, 57]. Zhang et al. (2011) reported a significant positive correlation between the dimensions of exhaustion and depersonalization and a student’s general psychological condition (using the SCL-90 symptoms self-evaluation scale) [57]. There was a significant negative correlation between the burnout dimension of personal achievement and a student’s psychological condition. Zhu et al. (2012) found that increased emotional exhaustion and a low sense of personal achievement were significantly positively associated with a student’s psychological condition (SCL-90 symptoms self-evaluation scale) [32]. In the third study, overall burnout and each of its constructs were independently positively associated with higher stress scores (r = 0.184~0.349) [30]. Overall burnout scores were negatively correlated with coping styles that focused on problem solving and asking for help(r = −0.383~ − 0.255) but positively correlated with coping styles that included self-blame, fantasy, retreat and rationalisation (r = 0.234~0.421) [30].

Discussion

Of the 33 included studies on burnout published in Chinese, most focused on demographic factors. More specifically, being male, experiencing poorer psychological functioning and being a more senior medical student were found to correlate with increased burnout. While the demographic factors were well substaintiated substantiated, our review shows a lack of research into other contributing factors. This is despite growing evidence to highlight the valuable role of contextual factors in interventions to reduce burnout [19].

The few studies in this review that explored contextual or social factors indicate these are important in the Chinese context. Findings that show both lack of social support (as a contributing factor to burnout) and a supportive environment in living quarters (as a mediating factor), affect rates of burnout flag the potential importance of context in both prevention and remediation strategies [35, 38, 39, 42]. Additional evidence regarding the contextual and social factors that promote or protect medical students from burnout is critical in order to develop contextually relevant and effective prevention strategies for this group.

Few studies targeted graduate students (those who already have their degree, also referred to as postgraduate). Greater exploration of the unique factors affecting graduate medical students are necessary due to the different curriculum, the substantial proportion of medical students in this group and their learning environment [39, 41]. The average age of enrollment for graduate medical students is generally higher then undergraduate students - this population may therefore encounter different contextual and social factors and pressures that influence their experience of burnout. Warranting further study of this specific group.

Implications

Three implications emerge from our review. The literature reviewed demonstrates that burnout is a challenge for medical students in China, but there is a lack of studies into factors beyond demographic variables that might predict increased burnout. This in turn means that the scope for evidence-based intervention development is limited. Secondly, even though demographic studies dominate, comparatively little is known about burnout in graduate medical students who have a markedly different demographic profile from their undergraduate counterparts [58]. Lastly, as research into interventions to prevent burnout is limited in China, there may be value assessing international interventions identified as effective within Chinese settings [19].

Limitations

Limitations apply to this study both in terms of the included studies and the review methods used. Non-published and non-empirical work were not included and as such may have led to the omission of relevant perspectives [59]. Bibliographic databases vary in their levels of specificity and sensitivity, impacting the number of articles returned and those that are considered relevant to the search terms [60]. Several databases in addition to manual searching were used to broaden coverage but relevant material may have been omitted. With the limitation number of the included articles, all the articles scored by MERSQI ranging from eight to13 were accepted to maximize the information. However, it might affect the quality of the conclusion.

Conclusions

The review findings highlight recognition of the problem of burnout amongst medical students in China, and that medical students are at risk of burnout. The evidence available is currently limited which is a barrier to developing effective, context-specific interventions. Additional studies that explore the contextual and social factors affecting burnout rates, the experiences of burnout in graduate students and that test existing interventions identified as effective in other settings in a Chinese context are needed.

Abbreviations

- CY:

-

Cynicism

- EX:

-

Exhaustion

- LRS:

-

Lian rong survey

- MBI:

-

Maslach burnout inventory

- MBI-GS:

-

MBI – general survey

- MBI-HSS:

-

MBI – human services survey

- MBI-SS:

-

MBI – student survey

- MERSQI:

-

Medical education research study quality instrument

- PE:

-

Professional efficacy

- PSMS:

-

Postgraduate student mentor scheme

- SCI:

-

Science citation index CY

- SCL-90:

-

Symptom checklist-90

- SPRF:

-

Survey with the possible related factors

References

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 1996.

Baigent M, Abi-Abdallah C, Achal R. RANZCP abstracts: prevalence of depression, anxiety and burnout in graduate entry medical students and its relationship to the academic year. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(S1):102.

Chang E, Eddins-Folensbee F, Coverdale J. Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):177–82.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005a;80(12):1613–22.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huschka MM, et al. A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006a;81(11):1435–42.

Dyrbye LN. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334.

Galán F, Ríos-Santos JV, Polo J, Rios-Carrasco B, Bullón P. Burnout, depression and suicidal ideation in dental students. Medicina oral Patología oral Y. Cirugia Bucal. 2014;19(3):E206–11.

Prinz P, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U, De Zwaan M. Burnout, depression and depersonalisation – psychological factors and coping strategies in dental and medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29(1):Doc10.

Youssef FF. Medical student stress, burnout and depression in Trinidad and Tobago. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):69–75.

Young L, Denize S. Competing interests: the challenge to collaboration in the public sector. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2008;28(1/2):46–58.

IsHak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10(4):242–5.

Almeida GD, Souza HR, Almeida PC, Almeida BD, Almeida GH. The prevalence of burnout syndrome in medical students. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo). 2016;43(1):6–10.

Chigerwe M, Boudreaux KA, Ilkiw JE. Assessment of burnout in veterinary medical students using the Maslach burnout inventory-educational survey: a survey during two semesters. BMC Medical Education. 2014;14(1):255.

Costa EF, Santos SA, Santos AT, Melo EV, Andrade TM. Burnout syndrome and associated factors among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Clinics. 2012;67(6):573–9.

Galán F, Sanmartín A, Polo J, Giner L. Burnout risk in medical students in Spain using the Maslach burnout inventory-student survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(4):453–9.

Mintz M, Youcha S, Twombly J, Krason M. Burnout among third year medical students [abstract: 28th annual meeting New Orleans, LA may 11–14, 2005]. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(S1):149.

Paro HB, Silveira PS, Perotta B, et al. Empathy among medical students: is there a relation with quality of life and burnout? PLoS One. 2014;9(4):E94133.

Santen SA, Holt DB, Kemp JD, Hemphill RR. Burnout in medical students: examining the prevalence and associated factors. South Med J. 2010;103(8):758–63.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–81.

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier CA. Conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53.

Cecil J, McHale C, Hart J, Laidlaw A. Behaviour and burnout in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:25209.

Haddad N. Western regional meeting abstracts: web-based visualization and problem solving as interventions for medical student burnout. J Investig Med. 2009;57(1):197–8.

Ling L, Qin S, Shen L. An investigation about learning burnout in medical college students and its influencing factors. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2014;1(1):117–20.

Wild K, Scholz M, Ropohl A, Bräuer L, Paulsen F, Burger PH. Strategies against burnout and anxiety in medical education – implementation and evaluation of a new course on relaxation techniques (Relacs) for medical students. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):E114967.

Maslach C, Leiter M. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:498–512.

WHO, 2016. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/database/en/. [retrieved 28 March 2017].

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Int Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme; 2006. p. Version 1.

Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, et al. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIMs medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903–7.

Yang DL. The study on group intervention in learning burnout of medical students. [master’s dissertation] Shanxi Medical University 2011. [Chinese].

Yang YX. Study on medical students’ professional commitment and its relationship with learning burnout and time management disposition. [master’s dissertation] Wan Nan Medical School 2013. [Chinese].

Zhu HC, Tan S, Li QQ, Jiang CY, Wang LJ, Sun S. Study on job burnout and mental health of seven-year-program clinical students in intern. Chinese Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases. 2012;64-65(Chinese):20.

Zhu Y, Bao C, Zhang ZH. Study on medical students’ learning burnout and learning achievements and their relationship. Chinese Journal of Medical Education 2012; 32(4): 536–538. [Chinese].

Causes LFY. Countermeasures of medical students’ burnout in clinical practice. China higher. Med Educ. 2012;06:93–4.

Xu P. A study on medical students’ learning burnout and its influential factors. [master’s dissertation] Nan Jing Medical School 2009. [Chinese].

Liao Y, Liu JY, HF W, et al. Initial study on higher vocational medical students’ learning burnout. Congqin. Medicine. 2011;09:924–6.

Di JH, Yang HX, Song AQ, Guo LY, Liu X, Zhang Y. Study on learning burnout of medical college students and its influential factors. China J Health Psychol. 2014;08:1255–7.

Jiang YM, Wang XP, Zheng Q, Wang WZ. Job burnout psychology of medical interns. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science) 2008; (S1): 17–20. [Chinese].

Chen X. Study on job burnout status and influencing factors among clinic postgraduates. [master’s dissertation] Central South University 2012. [Chinese].

Shen LJ, Fan GK, You JH. Medical postgraduates’ learning burnout and professional commitments. China J Health Psychol. 2012;07:1092–4.

Zheng XM, Li WY. An analysis on relevant factors of medical postgraduates’ learning burnout. J Xinjiang Med University. 2015;781-783(Chinese):06.

Li W. Relationship of social support with job burnout in 120 medical postgraduates. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2009; 7: 521–522, 527. [Chinese].

Jin WR, Wang XP, Chen MS, Ma JM, Jiang YM. Job burnout and SCL-90 in the medical interns. Chinese J Med Educ 2010; 30(2): 238-241. [Chinese].

Chen HY, Yuan S, Wang JX. Study on learning burnout and its relevant factors in medical university students. J Xinxiang Med Coll 2011; 06: 708-710. [Chinese].

Xiao J, Wang F, Ge H, Li FY, Lian YL. Relation between academic burnout and emotional intelligence among medical students. Chinese J Sch Health 2013; 12: 1442-1444, 1447. [Chinese].

Wang FF, Jiang HY. Investigation and analysis of current situation of medical students’ learning burnout. Jian Nan Wenxue. 2011;8:281.

Zhang L, Chen H. The correlation between the atmosphere of the dormitory and burnout in medical school. J Changchun Educ Inst 2013; 15: 91-92. [Chinese].

Li L, Shen Q, Shen LF. Study on the medical college students’ learning burnout and its influence factors. Chinese J Nurs Educ 2013; 05: 199-201. [Chinese].

Hu T, Zhou YH, Chen YW, et al. The study on burnout status among medical students in Xin Jiang Province. Zhong Guo Xiao Wai Jiao Yu Za Zhi (Chinese Journal of Off Campus Education 2014; 517 (S3): 522.

Wu HS, Lian R, Zhuang YJ. A study on the professional commitment and learning burnout of undergraduates in medical university. Journal of Chengdu University of TCM (Educational Science Edition). 2012;04:6–7.

Wei LQ, Ni JD, Lai ZF, Chen BQ. The status of stress, professionalism and burnout among medical students in Guang Dong Province. New West. 2014;10:65–6.

Fan YY, Wang ZG. Relationship between burnout and job choice among medical students. China Higher Med Educ. 2015;01(59):103.

Song RJ, Song XH, Yao AH, Li J. Relationship among, intrinsic motivation、psychological capital and academic burnout of medical students. Course Educ Res. 2013;22:242–3.

Song H, Xu W. The relationship between achievement motivation and burnout among medical students. China higher. Med Educ. 2015;05:33–4.

Li H, Liu BR, Liu XM, Dai XY. Initial investigation about occupational lassitude condition of clinical interns and nursing students. China higher. Med Educ. 2011;07:62–4.

Sun HM, Zhang LP, Wen ZD. Relationship between learning burnout and social support in medical students: mediating effect of academic self-efficacy. Educ Chinese Med. 2013;03:55–7. 63

Zhang YZ, Hu ZG, Yang MH. Study on job burnout and mental health of clinical interns. Occupation and Health 2011; 01: 1-4. [Chinese].

Mo,JY, Kong XM, Wang CM, MacIntyre R, Travaglia J, Balasooriya C. Comparative study on the medical education training model in China and Australia. Chinese J Med Educ Res 2015; 14(1): 1–6. [Chinese].

Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Publication bias in the social sciences: unlocking the file drawer. Science. 2014;345(6203):1502–5.

Watson RJD, Richardson PH. Identifying randomized controlled trials of cognitive therapy for depression: comparing the efficiency of Embase, Medline and PsycINFO bibliographic databases. Br J Med Psychol. 1999;72(4):535–42.

Fu, W. J. (2012). Comparative study on learning burnout among medical students and non medical students. Education Teaching Forum, (20), 32-33. [Chinese].

Li, Y.B (2015A). An investigaion on the affect on work and study by mental health status of postgraduate medical students studying in one tertiary hospital. Continuing Medical Education, 29(1):43-44. [Chinese].

Li, Y. B. (2015B). A hospital specializing in graduate mental health clinical investigation and research on learning burnout[master’s dissertation] XinJiang Medical University. [Chinese].

Li, Y.Z., Wu M. L. Research on Conditions of Medical Undergraduates’ Learning Burnout and the Influence factor in University of Medicine College, Journal of Chendu University of TCM (Educational Science Edition). 2014;16(3):65–69. [Chinese].

Acknowledgements

None to note.

Funding

This project was funded by Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine Science and Technology Fund Project (14XJ10061). The additional funding source of the following is to be noted as follows: 2015 SMC Outstanding Young Teachers of ShanghaiJiaotong University.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WC was responsible for leading the search process and synthesis process and for drafting the initial manuscript; RH and CB made substantial revisions to the manuscript and supported WC in its development including the search process; RM and JT were responsible for conceptualising the study, providing oversight of the review process, and drafting the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable to this review of published works.

Consent for publication

Not applicable to this review of published works.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chunming, W.M., Harrison, R., MacIntyre, R. et al. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review of experiences in Chinese medical schools. BMC Med Educ 17, 217 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1064-3