Abstract

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine use among Americans is prevalent. Originating in India, Ayurvedic medicine use in the United States has grown 57% since 2002. CAM accounts for a significant proportion of drug induced liver injury in India and China, but there have been only three reports of drug induced liver injury from Ayurvedic medications in the U.S. We report three cases of suspected Ayurvedic medication associated liver injury seen at a Southern California community hospital and review literature of Ayurvedic medication induced liver injury.

Case presentations

Three patients presented with acute hepatocellular injury and jaundice after taking Ayurvedic supplements for 90–120 days. First patient took Giloy Kwath consisting solely of Tinospora cordifolia. Second patient took Manjishthadi Kwatham and Aragwadhi Kwatham, which contained 52 and 10 individual plant extracts, respectively. Third patient took Kanchnar Guggulu, containing 10 individual plant extracts. Aminotransferase activities decreased 50% in < 30 days and all 3 patients made a full recovery. Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scores were 7–8, indicating probable causality. These products all contained ingredients in other Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicines with previously reported associations with drug induced liver injury.

Conclusions

These patients highlight the risk of drug induced liver injury from Ayurvedic medications and the complexity of determining causality. There is a need for a platform like LiverTox.gov to catalog Ayurvedic ingredients causing liver damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Originating in India thousands of years ago, Ayurveda is among the oldest healing systems in existence, with a focus on harmonious living and self-sustainability [1, 2]. Diseases are viewed in the context of their effects on an individual’s dosha or mind-body type with respect to energies of the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and ether [3]. Though illness prevention is promoted through lifestyle modifications, medicinal herbs are an integral part of Ayurveda [4]. Ayurveda is prominent in India, with the government recognizing and funding the practice, development, and research of Ayurvedic Medicine (AM) [5]. The Ayurvedic sector in India had an estimated market value of three billion USD in 2016 and its market value is expected to continue growing [6].

Though limited data exists quantifying the money spent on AM in the United States, recent trends suggest rising popularity [7]. Currently, the most popular Ayurvedic supplement in the United States is Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera), with sales in 2018 totaling over 7 million dollars, an increase of 165.9% from the year prior, according to a market report published by the American Botanical Council [8]. More broadly, the National Center for Health Statistics survey on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in 2015 showed that 241,000 American adults used AM, a nearly 57% increase from 2002 [9]. A survey of South Asian Americans in Northern California estimated that about 59% had used or were currently using AM but only 18% mentioned this to their healthcare providers [10]. Given these indicators of rising popularity, awareness of AM and its potential dangers is increasingly important for physicians in the United States.

CAMs make up a larger percentage of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) in Asia where CAM is more prevalent [11, 12]. One study of cirrhotic patients in India reported that of 1666 patients with cirrhosis, 35.7% had acute-on-chronic liver failure secondary to CAM-related DILI on presentation [11]. Like AM, in China, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is officially state-supported and institutionalized [13]. A survey of cancer patients of a large urban hospital in China revealed that more than 80% of patients were using TCM in conjunction with Western medicine [14]. In a series of 1985 cases of DILI in China, TCM was implicated in 28% of cases and an additional 28% of cases where TCM was taken in conjunction with Western medication [15]. In contrast, herbal and dietary supplements accounted for only 15.5% of liver injury among cases recorded by the Drug Induced Liver Injury Network in the U.S. [16]. There have been only three cases where specific Ayurvedic medications have been linked to liver damage in the U. S [17, 18] and seven in Europe [18,19,20,21,22]. Other case reports outside of India have come from Canada [23], South America [24], and Israel [25].

Within a 3 month-span, three cases of suspected AM-induced liver injury were seen at a Southern California community hospital. Using the updated Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM), we report these three patients and review the current literature of AM-associated DILI [26]. There are many plant species that are indigenous to India and China due to the proximities of these two countries. To highlight the common ingredients of AM and TCM, the herbal/plant ingredients of the AM supplements taken by these three patients were also cross-referenced with components of TCM that have been reported to be associated with liver injury. This report highlights the substantial challenges in assessing causality in cases of herbal product-induced liver injury.

Case presentation

Patient 1 is a 68-year-old South Asian female with a history of hypothyroidism, dyslipidemia and borderline diabetes mellitus who began taking an Ayurvedic supplement, Giloy Kwath, to improve her overall health. Her baseline blood work revealed mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 35 U/L and was otherwise normal. Four months later, routine follow-up blood work revealed acute hepatocellular injury: alkaline phosphatase (AP) 113 U/L, total protein (TP) 6.6 mg, albumin (alb) 4.1 g/dL, total bilirubin (t bili) 1.0 mg/dL, ALT 1016 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 844 U/L, and international normalizing ratio (INR) 1.0. Viral hepatitis A, B, C and E serologies were negative. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was weakly positive but anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA) and anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody (LKM) were negative. Her physical exam was normal. She was asymptomatic until 1 week later when she became jaundiced. At this time, she immediately stopped the supplement. Within 1 month of stopping, her liver tests became normal and remain normal 1 year later (Fig. 1a).

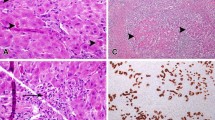

Patient 2 is a 38-year-old South Asian female with a history of hypothyroidism who began taking Manjishthadi Kwatham and Aragwadhi Kwatham for a skin rash. For the preceding 4 years prior to taking AM, her liver tests were normal. Four months after starting AM, she was initially evaluated for jaundice, fatigue, anorexia, and right upper quadrant discomfort. Her physical exam was significant for marked scleral icterus. Abdominal exam was unremarkable, without hepatomegaly. Blood work on admission revealed AP 175 U/L, TP 7.5 mg, alb 3.7 g/dL, t bili 10.7 mg/dL, ALT 760 U/L, AST 1020 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 923 U/L, INR 1.3, and IgG immunoglobulin 1238 mg/dL. Abdominal ultrasound revealed normal liver echogenicity with a smooth contour. MRI/MRCP confirmed a normal biliary tree. Her gallbladder wall was thickened, measuring 13 mm. Viral hepatitis A, B, C and E serologies were negative. Epstein-Barr IgM antibody was negative. Autoimmune serologies including ANA, SMA, and LKM were negative. Liver biopsy showed severely active pan-lobular hepatitis with bridging necrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. There was no definitive fibrosis (Fig. 2). She was treated with prednisone empirically for 6 weeks. Her liver tests normalized 6 weeks after presentation and have remained persistently normal 16 months after discontinuation of corticosteroids (Fig. 1b).

Histopathology showing Severely active panlobular hepatitis with panacinar necrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates: a. Low power (2x Magnification) The portal tracts are expanded at low power with diffuse inflammatory infiltration. b. Collapse of hepatocyte lobules illustrate the presence of panacinar necrosis. Note the remnants of the portal tracts marked by the presence of biliary ductules. (Magnification 10x). c. Remnant hepatic lobule showing infiltration by predominantly lymphocytes. Apoptotic hepatocytes were conspicuous (arrow). (Magnification 40x). d. Numerous plasma cells (arrows) are present in portal tracts showing interface activity. (Magnification 40x)

Patient 3 is a 46-year-old Hispanic female who is obese with menometrorrhagia who began taking Kanchnar Guggulu for her menses. Baseline liver tests taken 4 months prior to taking Kanchnar Guggulu were normal. Three months later, she became jaundiced with pruritus and a maculopapular rash. Her abdomen was non-tender and without hepatosplenomegaly. The remainder of her physical exam was unremarkable. Her laboratory studies revealed AP 140 U/L, TP 6.4 mg, alb 4.1 g/dL, t bili 15.0 mg/dL, ALT 1382 U/L, AST 878 U/L, and INR 1.1. Viral hepatitis A, B, C and E serologies were negative. ANA was weakly positive but SMA and LKM were negative. Ultrasound showed a normal size liver with normal echogenicity. There were no gallstones or biliary dilatation. The supplement was discontinued and after 8 weeks her liver tests returned to normal. They remain normal 6 months later (Fig. 1c).

Summary of the clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1 and the compilation of RUCAM for the Ayurvedic supplements are shown in Table 2.

All three patients took Ayurvedic medications in quantities as recommended, which contained plant ingredients that have been previously associated with liver injury in a large cases series [27] and case reports of AM-associated liver injury [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, 28] (Table 3). Patient 1 took Giloy Kwath that contained a single ingredient, Tinospora cordifolia, that was a component in eight preparations of Ayurvedic medications associated with liver injury reported in a large single center case series [27]. Patient 2 took 2 ayurvedic preparations; Manjishthadi Kwatham and Aragwadhadi Kwatham that contained 52 and 10 individual plant extracts, respectively (Table 3). Twenty-three extracts found in Manjishthadi Kwatham were associated with liver injury in prior literature, including Psoralea cordyfolia which was reported in two cases where this herb was the lone ingredient in the supplements taken by the patients [20, 21]. In addition to Tinospora cordifolia, which was also present in Giloy Kwath taken by Patient 1 and Manjishthadi Kwatham also taken by Patient 2, there were 8 other plant extracts in Aragwadhadi Kwatham associated with liver injury reported in prior literature, detailed in Table 3. Patient 3 took Kanchnar Guggulu, one of the 3 supplements taken by a patient with DILI reported by Dalal et al. [29]. Nine ingredients were found in other preparations associated with DILI described in other case reports or reviews: Cinnamomum tamala [17, 27], Cinnamomum zeylanicum [27], Elettaria cardamomum [17, 27], Emblica officinalis [27], Piper longum [23, 27], Piper nigrum [27], Terminalia belerica [17, 23, 27], Terminalia chebula [22], Zingiber officinale [19, 27].

The individual ingredients of these AM supplements were cross-referenced with components of TCMs that have been reported to be associated with liver injury (Table 4). Although Tinospora cordifolia (contained in Gilroy Kvath taken by patient 1 and in Manjishthadi Kwatham taken by patient 2) was not reported among TCM, a closely related plant species, Tinospora crispa, is contained in Bo Ye Qing Niu Dan which has been associated with liver injury [31, 32]. Azadirachta indica contained in Manjishthadi Kwatham is found in Ku Lian Zi as well as Cinnamomum tamala (Indian bay leaf) that is contained in Sairei To, which has been reported to cause DILI in TCM supplements [31–33].

An acute hepatocellular injury pattern was seen in all three patients. Two patients were jaundiced but none developed clinical signs of liver failure. Complete recovery was seen in all three cases. The patients underwent an exhaustive evaluation including viral and autoimmune serologies and imaging to rule out biliary tract or infiltrative diseases that was negative. None of the patients were re-exposed to the supplements and RUCAM scores indicated probable causality for DILI in the three patients, as detailed in Table 2.

Discussion and conclusions

Use of ayurvedic medicine in the U.S. is more popular and extends beyond Indo-Americans as evidenced by one of the 3 patients in this cases series who is Hispanic [9]. Despite the widespread use of AM, there is a relative paucity of publications on AM-associated liver injury. With 94 patients, Philips et al. compiled the largest list of Ayurveda and herbal medicine associated with severe liver injury from a single center from southern India. Five patients including one patient who underwent liver transplantation died [27]. Other clinical literature on the subject comprises case reports, case series, and broader reviews on herb-induced liver injury [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, 28, 31,32,33,34]. Initial patient complaints from herbal hepatotoxicity have ranged from asymptomatic liver function test abnormalities to acute liver failure requiring transplant and/or resulting in death [27, 34]. Our report of three patients with probable AM-induced liver injury highlights the pervasive challenges of evaluating causality in herbal-medication induced liver injury. One patient took the supplement Giloy Kwath (water extraction (decoction) of herb(s)), which contained only Tinospora cordifolia. This herb was also present in an AM, Manjishthadi Kwatham, taken by another patient in this report. Tinospora cordifolia was an ingredient found in eight different formulations of AMs associated with severe liver injury [27]. For a supplement with a single herb ingredient and a uniform pattern of liver injury across multiple occurrences, such as the recent case series involving Withania somnifera (also known as Ashwagandha) [18], assignment of causality can be determined with greater certainty. There are other case reports of AM-associated liver injury involving a single agent; Bakuchi Powder/Babchi Seeds/Bakuchiol which consist of Psoralea corylifolia [21], Bristly Luffa consisting of Luffa echinate [35], and Cantella asiatica [22, 24]. However, this kind of clear association is relatively uncommon.

As in two of the patients in this series, other case reports of AM-associated liver injury involve patients taking multiple preparations that may contain numerous ingredients [20, 23, 29]. For example, one of our patients took two preparations that contained 52 and 10 individual ingredients, respectively. The large number of components is not unusual for Ayurvedic preparations. On analysis of the compendium by Philips et al. [27], 8 of the listed 27 Ayurvedic medications reported to be associated with liver injury had detailed ingredient lists available online. The mean and median number of individual herbs in these medications was 19.8 and 9, respectively, ranging from 1 to 71 ingredients per supplement (see Supplement 1). Notably, this search for ingredients may be limited by conducting it retrospectively, as ingredient listings may have since changed since their usage in the review. There were 33 total components in the products taken by patient 2 that were listed as ingredients in the preparations associated with previous cases of AM-induced liver injury; 11 such ingredients were found in the AM products taken by patient 3. While this may indicate overlap in a component or components responsible for hepatic damage, it may also simply demonstrate the ubiquity of certain ingredients in Ayurvedic medications, which adds to the challenge of attributing causality.

Another inherent challenge in evaluating toxicity related to AM and other herbal supplements is the lack of accurate data regarding quantities and dosing. For most cases, the prevailing theory of the mechanism of herbal induced liver injury is idiosyncratic and therefore, dosing is not a parameter that considered in evaluating causation [26].

To tabulate a comprehensive list of Ayurvedic compounds associated with liver injury, we performed a literature search for all articles in English discussing Ayurveda and liver injury, damage, or hepatotoxicity in humans. Articles were excluded if they detailed hepatoprotective effects. The literature review for AM-associated herbal supplement induced liver injury in humans yielded 50 results with the following distribution according to PubMed archiving: 10 case reports/series, 9 reviews of AM, 2 clinical studies, and 29 journal articles. After eliminating off-topic matches, 12 were deemed to be directly relevant for the purpose of this summary. Articles excluded were among the following categories: discussions of uses of an herb or supplement unrelated to liver injury, pharmacologic properties of a substance unrelated to liver injury, heavy metal contamination in AM, cancer unrelated to AM hepatotoxicity, and liver physiology unrelated to hepatic injury. After analyzing the compounds listed and cross referencing their constituent ingredients from available sources online (shown in Supplement 1), a number of substances were found to be common ingredients in Ayurvedic medications causing liver injury: Phyllanthus emblica with 12 unique occurrences, Withania somnifera with 11, Zingiber officinale with 11, and numerous others (see Supplement 2). Importantly, these compounds were not all specifically implicated in their respective studies but rather recurrently present in substances taken by patients with DILI after examination of each’s components through an online search.

With this information in mind, it is important to note the inherent limitations of this type of correlational summation. For instance, Zingiber officinale, though linked to 11 Ayurvedic medications [19, 27, 29] and TCM [31,32,33] associated with live injury, is ginger, a widely used household spice. While the ingredient could be hepatotoxic, its prevalence may also be explained by the fact that it is a common additive in Ayurvedic supplements. Similarly, Piper nigrum or black pepper, has 5 occurrences in medications causing liver injury, and several other compounds (see Supplement 2). This said, other commonly used products have been linked to acute liver injury, a notable example being green tea extract [36]. Until larger and more focused research is conducted, this list in Supplement 2 clearly limited in practicality by its correlational nature and should serve only as a starting ground for more focused future investigations and efforts to tabulate offending herbs or substances. Moreover, as previously mentioned, certain compounds’ ingredients were retrospectively retrieved and may not accurately reflect the exact product taken at the time of each initial case.

Like Ayurveda, TCM, which includes the use of herbs, has evolved over thousands of years. Comparatively, more research exists on Chinese herbal medications and liver injury; however, Ayurvedic and Chinese herbal medications share many ingredients. In a compilation of 57 traditional Chinese medications associated with liver injury, 18 contained similar compounds in Ayurvedic medications associated with liver injury, shown in Table 4. Moreover, an additional 5 species of the same genus as those found in the Ayurvedic medications were identified. Teschke and others have created extensive compilations of TCM herbs associated with hepatoxicity [31,32,33,34]. Assigning causality to TCM is fraught with the same challenges as AM-associated liver injury. We discovered several compounds associated with liver injury in TCM contained in the AM products taken by our three patients: Psoralea corylifolia, Zingiber officinale, Piper nigrum, Cinnamomum verum, Cinnamomum tamala, Azadirachta indica, Eclipta prostrata, Cyperus rotundus, and Gentiana kurroo [31,32,33]. Again, as noted above, these simply represent shared associations with liver injury in AM and TCM, which may indicate hepatotoxicity, the popularity of certain herbs in traditional medicinal preparations, or both. A 2019 review by Byeon et al. of all documented herb-induced liver injury contained substances found Psoralea corylifolia, which was an ingredient of Manjishthadi Kwatham taken by patient 2 in this report, to be the second most common overall precipitant from the review, with 41 occurrences [37].

The spectrum of the histological findings on liver biopsy are just as diverse and varied as the ingredients of AM that are suspected to be causative for DILI. The most common finding present on liver biopsy has been a non-specific chronic hepatitis, present in 85% of cases reported by Philips et al. [27]. However, more severe findings have been reported and include sub-massive hepatic necrosis, pan-acinar necrosis, bridging necrosis, granulomatous hepatitis, steatohepatitis, and cholestatic hepatitis [17, 19, 21, 24, 27]. Features ranging from active cholangitis, biliary proliferation, and non-specific injury typical of DILI have also been reported [21, 25, 29]. Fibrosis was present in 77% of patients in one study [27], indicating a chronic injury in the vast majority of patients, which may be attributable to long term usage of AM. The variety of histological appearances of AM related DILI presents additional challenges in routine clinical diagnosis of this etiology and further complicates attribution of the injury to one specific ingredient in AM or TCM supplements.

As AM and TCM gain wider use in the West, there is a need to develop a central registry to document herbal supplements and their constituent ingredients that have been reported to cause liver injury similar to Livertox.nih.gov, a registry of medications associated with DILI. Complicating the matter is that supplements in the United States are unregulated. The chemical composition of herbal supplements is not verified and therefore analysis is additionally challenging.

In conclusion, our case series represents three of the few documented cases of AM-induced liver injury in the United States. As Ayurvedic supplement use becomes more popular in the U.S. and globally, recognition of AM induced liver injury will become crucial. However, the complexity of supplements taken by patients make causality difficult to discern. Investigating specific ingredients in Ayurvedic medications and other herbal supplements associated with liver injury would help evaluate current correlational relationships [11]. This effort would depend on a reliable catalog of constituent ingredients, in a platform similar to that of LiverTox.gov. This would facilitate quicker recognition of offending agents when diagnosing patients with herb-induced liver injury and safer consumption of Ayurvedic as well as other complementary and alternative medicine preparations by patients.

Availability of data and materials

All clinical data are available by contacting Dr. Tse-Ling Fong.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Ayurvedic medication

- USD:

-

U.S. dollars

- CAM:

-

Complementary and alternative medicine

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine

- DILI:

-

Drug-induced liver injury

- RUCAM:

-

Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- TP:

-

Total protein

- alb:

-

Albumin

- t bili:

-

Total bilirubin

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase INR international normalising ratio

- ANA:

-

Anti-nuclear antibody

- SMA:

-

Anti-smooth muscle antibody

- LKM:

-

Anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MRI/MRCP:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography

References

Mukherjee PK, Harwansh RK, Bahadur S, et al. Development of Ayurveda - tradition to trend. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;197:10–24.

Gokani T. Ayurveda--the science of healing. Headache. 2014;54(6):1103–6.

Chopra AS. Ayurveda. In: Selin H, editor. Medicine across cultures: history and practice of medicine in non-western cultures: Kluwer Academic; 2003. p. 75–83.

Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1–23.

Jaiswal YS, Williams LL. A glimpse of Ayurveda - the forgotten history and principles of Indian traditional medicine. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016;7(1):50–3.

Mukherjee A. Ayurveda industry, market size, strength and way forward. Confederation of Indian Industry. 2018:5–7.

Chaudhary A, Singh N. Contribution of world health organization in the global acceptance of Ayurveda. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2011;2(4):179–86.

Smith T, Gillespie M, Eckl V, Knepper J, Reynolds CM. Herbal supplement sales in US increase by 9.4% in 2018. HerbalGram. American Botanical Council. 2019;123:62–73.

Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ. Expenditures on complementary health approaches: United States, 2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2016;95:1–11.

Satow YE, Kumar PD, Burke A, Inciardi JF. Exploring the prevalence of Ayurveda use among Asian Indians. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(10):1249–53.

Philips CA, Augustine P, Rajesh S. Y PK, Madhu D. complementary and alternative medicine-related drug-induced liver injury in Asia. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7(3):263–74.

Lin X, Gu Y, Zhou Q, Mao G, Zou B, Zhao J. Combined toxicity of heavy metal mixtures in liver cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2016;36(9):1163–72.

Xu J, Yang Y. Traditional Chinese medicine in the Chinese health care system. Health Policy. 2009;90(2–3):133–9.

McQuade JL, Meng Z, Chen Z, et al. Utilization of and attitudes towards traditional Chinese medicine therapies in a Chinese Cancer hospital: a survey of patients and physicians. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:504507.

Zhu Y, Niu M, Chen J, et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: comparison between Chinese herbal medicine and Western medicine-induced liver injury of 1985 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(8):1476–82.

Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. drug-induced liver injury network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399–408.

Philips CA, Paramaguru R, Augustine P. Severe alcoholic hepatitis in a Teetotaler. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(8):1260–1.

Björnsson HK, Björnsson ES, Avula B, et al. Ashwagandha-induced liver injury: a case series from Iceland and the US drug-induced liver injury network. Liver Int. 2020;40(4):825–9.

Douros A, Bronder E, Andersohn F, et al. Herb-induced liver injury in the Berlin case-control surveillance study. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(1):114.

Teschke R, Bahre R. Severe hepatotoxicity by Indian Ayurvedic herbal products: a structured causality assessment. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8(3):258–66.

Smith DA, MacDonald S. A rare case of acute hepatitis induced by use of Babchi seeds as an Ayurvedic remedy for vitiligo. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013200958.

Dantuluri S, North-Lewis P, Karthik SV. Gotu Kola induced hepatotoxicity in a child - need for caution with alternative remedies. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(6):500.

Tremlett H, Fu P, Yoshida E, Hashimoto S. Symptomatic liver injury (hepatotoxicity) associated with administration of complementary and alternative products (Ayurveda-AP-mag capsules(®)) in a beta-interferon-treated multiple sclerosis patient. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(7):e78–9.

Jorge OA, Jorge AD. Hepatotoxicity associated with the ingestion of Centella asiatica. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97(2):115–24.

Shiyovich A, Sztarkier I, Nesher L. Toxic hepatitis induced by Gymnema sylvestre, a natural remedy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340(6):514–7.

Danan G, Teschke R. RUCAM in drug and herb induced liver injury: the update. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;17(1):14.

Philips CA, Paramaguru R, Joy AK, Antony KL, Augustine P. Clinical outcomes, histopathological patterns, and chemical analysis of Ayurveda and herbal medicine associated with severe liver injury-a single-center experience from southern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37(1):9–17.

Teschke R, Wolff A, Frenzel C, et al. Herbal hepatotoxicity: a tabular compilation of reported cases. Liver Int. 2012;32(10):1543–56.

Dalal KK, Holdbrook T, Peikin SR. Ayurvedic drug induced liver injury. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(31):1205–9.

Gunturu KS, Nagarajan P, McPhedran P, Goodman TR, Hodsdon ME, Strout MP. Ayurvedic herbal medicine and lead poisoning. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:51.

Teschke R, Zhang L, Long H, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine and herbal hepatotoxicity: a tabular compilation of reported cases. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14(1):7–19.

Teschke R, Wolff A, Frenzel C, Schulze J. Review article: herbal hepatotoxicity--an update on traditional Chinese medicine preparations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(1):32–50.

Chow HC, So TH, Choi HCW, Lam KO. Literature review of traditional Chinese medicine herbs-induced liver injury from an oncological perspective with RUCAM. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419869479.

Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(1):3–17.

Giri S, Lokesh CR, Sahu S, Gupta N. Luffa echinata: healer plant or potential killer. J Postgrad Med. 2014;60(1):72–4.

Oketch-Rabah HA, Roe AL, Rider CV, et al. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) comprehensive review of the hepatotoxicity of green tea extracts. Toxicol Rep. 2020;7:386–402.

Byeon JH, Kil JH, Ahn YC, Son CG. Systematic review of published data on herb induced liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;233:190–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Christopher M. Karousatos: Analysis of data, writing and approval of final version of manuscript. Justin K. Lee: Collection and analysis of data, approval of final version of manuscript. David R. Braxton: Analysis of data, writing and approval of final version of manuscript. Tse-Ling Fong: Study concept, collection and analysis of data, writing and approval of final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was waived by Institutional Review Board of Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian.

Patients gave written consent for publication of their clinical presentations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karousatos, C.M., Lee, J.K., Braxton, D.R. et al. Case series and review of Ayurvedic medication induced liver injury. BMC Complement Med Ther 21, 91 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03251-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03251-z