Abstract

Background

Higher physical activity levels are associated with lower breast cancer-specific mortality. In addition, the metabolic syndrome is associated with higher breast cancer-specific mortality. Whether the physical activity association with breast cancer mortality is modified by number of metabolic syndrome components (cardiometabolic risk factors) in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer remains unknown.

Methods

Cardiovascular risk factors included high waist circumference, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Breast cancers were verified by medical record review. Mortality finding were enhanced by serial National Death Index queries. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate associations between baseline physical activity and subsequent breast cancer-specific and overall mortality following breast cancer diagnosis in Women’s Health Initiative participants. These associations were examined after stratifying by cardiometabolic risk factor group.

Results

Among 161,308 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) participants, 8543 breast cancers occurred after 9.5 years (median) follow-up in women, additionally with information on cardiometabolic risk factors and physical activity at entry. In multi-variable analyses, as measured from cancer diagnosis, higher physical activity levels were associated with lower all-cause mortality risk (hazard ratio [HR] 0.86, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78–0.95, trend P < 0.001) but not with breast cancer-specific mortality (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.04, trend P = 0.09). The physical activity and all-cause mortality association was not significantly modified by cardiometabolic risk factor number.

Conclusions

Among women with early-stage breast cancer, although higher antecedent physical activity was associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality, the association did not differ by cardiometabolic risk factor number.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metabolic syndrome is a clustering of metabolic dysfunctions that includes at least three of the following: high waist circumference, triglycerides, blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose; and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Among other associated morbidities, the metabolic syndrome has been associated with higher risk of breast cancer-specific mortality [1, 2].

Higher physical activity levels, compared to lower levels, measured prior to breast cancer diagnosis have been associated with statistically significantly lower all-cause mortality among women diagnosed with breast cancer [3, 4]. Higher physical activity levels have been shown to influence the metabolic syndrome in women with breast cancer [5] and in other settings [6] where exercise programs significantly reduced metabolic syndrome components. However, it is unknown whether presence of the metabolic syndrome modifies the favorable physical activity influence on breast cancer. Therefore, we examined the association between physical activity and all-cause mortality after breast cancer and breast cancer-specific mortality to determine whether associations were modified by the number of metabolic syndrome components. We hypothesized that women with breast cancer having more metabolic syndrome components would be more likely to benefit from higher pre-diagnosis physical activity levels in terms of breast cancer mortality.

Methods

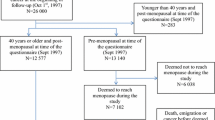

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) recruited 161,308 post-menopausal women aged 50–79 with anticipated 3-year survival from 40 US clinical centers between 1993 through 1998. Details of the WHI have been reported [7]. All protocols were approved by institutional review boards and participants gave written informed consent. Eligible for the current analyses were participants with incident, invasive, non-metastatic breast cancer (n = 10,124), additionaly with baseline measurement of cardiometabolic risk factors (n = 8543).

Participant characteristics were collected using questionnaires at entry regarding breast cancer risk factors, demographics, physical activity, medical history, and social economic status. Blood pressure was measured using standardized procedures by certified personnel with two determinations taken 30 s apart and averaged. Waist circumference, weight, and height were measured by trained personnel using a standardized approach with body mass index (BMI) computed as weight (kg)/[height (m)]2.

Physical activity was assessed by questionnaire. Participants were asked about walking outside the home by duration and by speed categories; metabolic equivalent task (MET) values were assigned for walking (average, 3 METs; fast, 4 METs; and very fast 4.5 METs). For recreational physical activity, participants were asked how often and for how long they exercised at various intensity levels. Vigorous-intensity activities included aerobics, jogging, tennis, and swimming laps while moderate-intensity activities included biking, exercise machine use, calisthenics, easy swimming, and dancing. The information on walking and recreational physical activity was used to generate a hours/week (h/wk) variable which was combined with MET values for each activity.to generate the final MET-h/wk variable, as previously described [8].

A convenience construct was used to assess metabolic syndrome components, referred to here as “cardiometabolic risk factors” which were determined at entry and included: (1) measured high waist circumference, (2) measured high blood pressure, (3) history of high cholesterol, and (4) history of diabetes, as previously described [4]. Information on triglyceride levels was not available. High blood pressure was defined as systolic ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg, or a normal blood pressure and use of anti-hypertensive medications identified during in-clinic medication inventory. High waist circumference was defined as ≥ 88 cm [8]. High cholesterol was determined using the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had high cholesterol requiring medication?” or cholesterol-lowering medication use identified during in-clinic medication inventory. Diabetes was determined using the question “Did a doctor ever say that you had sugar diabetes or high blood sugar when you were not pregnant?” or by use of diabetes-related medication use identified during in-clinic medication inventory. This diabetes definition has been validated and is consistent with medication inventories [9].

In the WHI clinical trials, participants were followed for clinical outcomes every 6 months during the 8.5-year (median) intervention period, then annually. WHI observational study participants were followed annually throughout. Breast cancers were initially confirmed with medical record review at the clinical centers by trained physician adjudicators with final confirmation and coding at the clinical coordinating center. Reports of death and cause of death were verified by medical records or death certificate review at the clinical coordinating center [10]. Mortality findings were enhanced by serial National Death Index queries resulting in survival information which was 98% complete [11]. Breast cancer therapy was directed by participant’s own physicians. Current study outcomes of interest included all-cause mortality and breast cancer-specific mortality, both measured from breast cancer diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Cardiometabolic risk groups were categorized into 0, 1–2, and 3–4 components as incorporated in previous analyses [12]. Associations of physical activity with all-cause mortality after breast cancer and breast-cancer specific mortality were assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models and trend tests for the ordinal variable. Mortality outcomes were measured from breast cancer diagnosis. Multivariable models were adjusted for confounders found significant (adjusts for age group, race/ethnicity alcohol intake, smoking status, BMI kg/m2, # of metabolic risk factors, hormone receptor status, grade, HER2/NEU number of examined lymph nodes, number of positive lymph nodes, tumor size, and stage) in univariate analyses. Effect modification with cardiometabolic risk factors was assessed by adding the cross-product term of physical activity and cardiometabolic risk groups to the multivariable model.

Results

At entry, women with three or four cardiometabolic risk factors, compared to those with no risk factors, were older, have higher BMI, were more likely to be Black, report fair/poor health, to have diabetes, higher blood pressure and report less physical activity (Table 1).

Higher physical activity levels at entry were inversely associated with high waist circumference, history of diabetes, high blood pressure, and higher cardiometabolic composite scores (all P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Physical activity levels and cardiometabolic risk factors were determined at study entry. Incident breast cancers were diagnosed 9.5 years (median) from entry and were subsequently additionally followed for 9.5 years (median) after breast cancer diagnosis. In the multivariable models (Table 2), higher physical activity levels were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality following a breast cancer diagnosis (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.95, trend P < 0.001) but were not associated with lower breast cancer-specific mortality (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.04, trend P = 0.09). After stratifying by cardiometabolic risk factor groups, the association between higher physical activity at entry and lower all-cause mortality following breast cancer diagnosis was found only in participants with 1–2 metabolic risk factors. There was no statistically significant interaction between cardiometabolic risk factor group and associations of physical activity and breast cancer outcomes.

Discussion

In prior WHI reports, both higher physical activity levels [13] and fewer cardiometabolic risk factors [4] were associated with lower all-cause mortality following a breast cancer diagnosis in postmenopausal women. While in the current analyses, with longer follow-up, higher physical activity levels continued to be significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality following a breast cancer diagnosis, no significant interaction was seen between physical activity, number of cardiometabolic risk factors and breast cancer mortality. Thus, our study hypothesis was not supported.

To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between physical activity, cardiometabolic risk factors, and mortality among women with breast cancer. Current study findings support the established inverse association between physical activity and all-cause mortality among breast cancer survivors [3] as current study participants with breast cancer with higher physical activity levels had lower all-cause mortality. However, current study findings did not demonstrate that cardiometabolic risk factors modified this association.

In contrast, cardiometabolic risk factors modified the effect of a dietary intervention on breast cancer outcomes, as evaluated in the WHI randomized Dietary Modification (DM) trial. In the WHI DM trial, all 48,835 participants were free of prior breast cancer at entry and were randomly assigned to a low-fat dietary-pattern (40%) or a usual diet comparison group (60%). Changes associated with the dietary intervention included reduced fat intake; increased fruit, vegetable, and grain consumption, and weight reduction [15]. While the trial was ongoing, the dietary intervention was also shown to reduce metabolic syndrome components when determined 3 years after entry [14]. After long term, 19.6-year (median) follow-up, compared to women in the comparison group, women in the low-fat dietary intervention group had a statistically significant 21% reduction in death from breast cancer measured from study entry (132 [0.037% annualized risk] v 251 [0.047%] deaths, respectively; HR 0.79 95% CI 0.64–0.97, P = 0.02) [15]. In a secondary analysis, women with 3–4 cardiometabolic risk factors, compared to women with no cardiometabolic risk factors, had a significantly higher risk of death from breast cancer, however, those with 3–4 cardiometabolic risk factors randomized to the dietary intervention had a statistically significant 69% reduction in this risk (HR 0.31 95% CI 0.14–0.69, interaction P = 0.01, compared to women with 0 or 1–2 risk factors) [12]. Thus, in a randomized clinical trial setting, women having more metabolic syndrome components were more likely to benefit, in terms of reduction in breast cancer mortality, from a lifestyle intervention, randomization to a low-fat dietary pattern.

There is a study which could assess relationships among physical activity, cardiometabolic risk factors, and breast cancer outcome. The ongoing Women's Health Initiative Strong and Healthy (WHISH) pragmatic physical activity intervention trial has completed randomization of 49,331 postmenopausal women testing whether a physical activity intervention reduces major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [16]. A secondary analysis of associations among physical activity, metabolic syndrome components and breast cancer mortality would be well-powered to provide definitive assessment.

Current study strengths include the large sample size, prospective study design, use of a previously developed physical activity assessment tool, long follow-up and centralized, adjudicated breast cancer incidence and mortality outcomes. The study has limitations. First, the observational design precludes causal inferences. Second, reliance on questionnaire data for diabetes and cholesterol and reliance on baseline cardiometabolic risk factors and recreational physical activity assessment are limitations as well. Regarding the interval between cardiometabolic risk factor assessment, in a prior analysis in a WHI subgroup, metabolic syndrome status measured earlier in time (more years prior to breast cancer diagnosis) was more predictive of breast cancer risk compared to determinations made closer to breast cancer diagnosis [17, 18].

Conclusions

In summary, the association of higher physical activity level with lower mortality risk in postmenopausal women with breast cancer did not differ significantly across cardiometabolic risk factor groups. Future studies could consider examining changes in cardiometabolic risk factors and physical activity patterns over time among women with breast cancer.

Availability of data and materials

The following data will be made available beginning 1 July 2022: the identified participant data and data dictionary (information about data sharing for the Women’s Health Initiative can be found at: www.WHI.orgy/researchers/data/Documents/WHI%20Data%20Sharing%20Statement.pdf. For these analyses, data will be publicly available two years after publication of this article. The following supporting documents are available: statistical/analytical and informed consent form (www.whi.org/researchers/studydoc/SitePages/Protocol%20and%20Consents.aspx).

References

Calip GS, Malone KE, Gralow JR, Stergachis A, Hubbard RA, Boudreau DM. Metabolic syndrome and outcomes following early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148(2):363–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3157-6.

Dibaba DT, Ogunsina K, Braithwaite D, Akinyemiju T. Metabolic syndrome and risk of breast cancer mortality by menopause, obesity, and subtype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174(1):209–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-5056-8.

Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Association between physical activity and mortality among breast cancer and colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1293–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu012.

Simon MS, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Hastert TA, Manson JE, Cespedes Feliciano EM, Neuhouser ML, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors and survival after breast cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer. 2018;124(8):1798–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31230.

Dieli-Conwright CM, Wong L, Waliany S, Bernstein L, Salehian B, Mortimer JE. An observational study to examine changes in metabolic syndrome components in patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2646–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30104.

Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1212914.

Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, Lund B, Hall D, Davis S, et al. Implementation of the Women’s Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S5-17.

Lemieux S, Prud’homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP. A single threshold value of waist girth identifies normal-weight and overweight subjects with excess visceral adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(5):685–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/64.5.685.

Jackson JM, DeFor TA, Crain AL, Kerby TJ, Strayer LS, Lewis CE, et al. Validity of diabetes self-reports in the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2014;21(8):861–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0000000000000189.

Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, Kooperberg C, Stanford J, Nevitt M, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S122–8.

Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and equifax nationwide death search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(11):1016–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191.

Pan K, Aragaki AK, Neuhouser ML, Simon MS, Luo J, Caan B, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and breast cancer mortality by metabolic syndrome components: a secondary analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-021-01379-w.

Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Manson JE, Thomson CA, Sternfeld B, Stefanick ML, et al. Physical activity and survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4(4):522–9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-10-0295.

Neuhouser ML, Howard B, Lu J, Tinker LF, Van Horn L, Caan B, et al. A low-fat dietary pattern and risk of metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative. Metab Clin Exp. 2012;61(11):1572–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2012.04.007.

Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Anderson GL, Pan K, Neuhouser ML, Manson JE, et al. Dietary modification and breast cancer mortality: long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1419–28. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.19.00435.

Stefanick ML, King AC, Mackey S, Tinker LF, Hlatky MA, LaMonte MJ, et al. Women’s Health Initiative strong and healthy pragmatic physical activity intervention trial for cardiovascular disease prevention: design and baseline characteristics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(4):725–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa325.

Kabat GC, Kim M, Chlebowski RT, Khandekar J, Ko MG, McTiernan A, et al. A longitudinal study of the metabolic syndrome and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(7):2046–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-09-0235.

Kabat GC, Kim M, Caan BJ, Chlebowski RT, Gunter MJ, Ho GY, et al. Repeated measures of serum glucose and insulin in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(11):2704–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24609.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following investigators in the WHI Program: Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Dale Burwen, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller. Clinical Coordinating Center: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg. Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH)Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA) Rowan T. Chlebowski; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker. For a list of all the investigators who have contributed to WHI science, please visit: http://www.whi.org/publications/WHI_investigators_longlist.pdf.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32 and 44221) for project support, and grant R25CA203650 from the Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer Training Workshop for collaborative support (CDC, MI, RC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept—CDC, RC, JM, RN; Data analysis—RN; manuscript writing and final review—all authors; CMD, RAN, MSS, MI, MLN, KWR, TEC, JEM, RN, AS, ML, LQ, CAT, CHK, KP, RTC, and JM; all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the WHI study at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Rowan Chlebowski is a consultant for Novartis, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Merck, Immunomedics, and Puma and received honorarium from Novartis and AstraZeneca. None of the other authors report any conflict of interest related to this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dieli-Conwright, C.M., Nelson, R.A., Simon, M.S. et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors, physical activity, and postmenopausal breast cancer mortality: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. BMC Women's Health 22, 32 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01614-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01614-3