Abstract

Purpose

Many patients living beyond cancer experience significant unmet needs, although few of these patients are currently reviewed by specialist palliative care teams (SPCTs). The aim of this narrative review was to explore the current and potential role of SPCTs in this cohort of patients.

Methods

A search strategy was developed for Medline, and adapted for Embase, CINAHL, and PsycInfo. Additionally, websites of leading oncology, cancer survivorship, and specialist palliative care organisations were examined. The focus of the search was on individuals living beyond cancer rather than other groups of cancer survivors.

Results

111 articles were retrieved from the search for full text review, and 101 other sources of information were identified after hand searching the reference lists of the full text articles, and the aforesaid websites. The themes of the review encompass the definition of palliative care/specialist palliative care, current models of specialist palliative care, core activities of SPCTs, relevant expertise of SPCTs, and potential barriers to change in relation to extending their support and expertise to individuals living beyond cancer. The review identified a paucity of evidence to support the role of SPCTs in the management of patients living beyond cancer.

Conclusions

Individuals living beyond cancer have many unmet needs, and specific services are required to manage these problems. Currently, there is limited evidence to support the role of specialist palliative care teams in the management of this cohort of people, and several potential barriers to greater involvement, including limited resources, and lack of relevant expertise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“Cancer survivor” is a ubiquitous term, which has various connotations amongst healthcare professionals, patients with cancer, family carers, and the general population [1]. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the USA states that “an individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis through the balance of life. There are many types of survivors, including those living with cancer and those free of cancer” [2]. The NCI definition is widely quoted, and has been adopted to a greater or lesser extent by many other national and international organisations. However, the colloquial (general population) meaning of a survivor is “one remaining alive after some disaster in which others perish”, i.e. a cancer survivor is an individual that has been “cured” of cancer [3]. This disparity in meaning is highlighted by studies investigating the acceptability of the term cancer survivor amongst different cohorts of patients with cancer [4].

The NCI acknowledges this disparity, and notes that “years ago, some suggested that the definition should only include people who were cancer-free for a minimum amount of time after their diagnosis”, and goes on to say that “this term (cancer survivor) is meant to capture a population of those with a history of cancer rather than to provide a label that may or may not resonate with individuals” [2]. The NCI definition of cancer survivor is supported by a three phase model of cancer survivorship (Fig. 1), which specifically includes patients with “end stage cancer”, but surprisingly not individuals that have been cured of cancer [2]. In response to concerns about nomenclature, the terms “living with cancer”, “living through cancer”, and “living beyond cancer” (either alone or together, e.g. “living with and beyond cancer”) have been introduced [5]: living beyond cancer “refers to post-treatment and long-term survivorship” (i.e. individuals that have been potentially cured of cancer) [6].

National Cancer Institute phases of cancer survivorship [2]

Many cancer survivors experience significant unmet needs, which encompass the continuum of physical, psychological, spiritual, and social domains (Table 1) [7], and which relate to the cancer (directly or indirectly), the cancer treatment, and/or the presence of a chronic (potentially life-limiting) disease [8]. Indeed, these unmet needs are the primary driver for the ongoing discussions around greater involvement of specialist palliative care teams (SPCTs) in the management of individuals living beyond cancer, and similarly underserved groups of cancer survivors, e.g. cancer patients with stable disease on maintenance anticancer treatment. Importantly, there is significant heterogeneity amongst individuals in the same phase, and especially between individuals in different phases, in terms of the problems experienced, and the most suitable options for management [9]. Hence, healthcare services for cancer survivors need to be tailored to the different phases / subgroups of patients (and then personalised to the individual patient).

The aim of this narrative review article is to explore the potential for greater involvement of SPCTs in supporting individuals living beyond cancer as already defined [6], rather than other cohorts of “cancer survivors”: the objectives are to define palliative care (and specialist palliative care), to outline current models of specialist palliative care, to outline the core activities of SPCTs, to determine the relevant expertise of SPCTs, and to highlight the potential barriers to change.

Methodology

A literature search was initially undertaken in May 2023, and subsequently updated in January 2024. The search included four electronic databases (Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo), the internet (i.e. websites of leading oncology, cancer survivorship, and specialist palliative care organisations), and hand searching of specialist palliative care textbooks. A broad search strategy was developed for Medline (Appendix 1), and adapted as needed for the other electronic databases: the electronic databases were searched from their inception to the present. Basically, we were seeking articles relating to the role / potential role of specialist palliative care teams in the management of cancer survivors (and specifically individuals living beyond cancer). All types of articles were considered, including editorials / commentaries, review articles, and particularly original research (including conference abstracts). Articles relating to children were not reviewed. Non-English articles were not reviewed, unless there was an English abstract (which was reviewed).

EndNote 20™ bibliographic software (Clarivate Analytics LLP, USA) was used to store the retrieved articles, whilst Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia) was used to screen these retrieved articles. The two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts for full text articles to review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The two authors also independently reviewed the full text articles, and extracted the relevant information using a review-specific template: this information was predetermined, and was collated using a PICOS framework (i.e. Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design). The reference lists of all retrieved full text articles were reviewed for further potential articles or sources of information.

Results

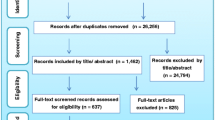

The searches of the literature identified 5458 articles, which included 191 duplicate articles that were removed, and 5156 “irrelevant” articles that were excluded (on the basis of their titles and abstracts). Thus, 111 articles from the search underwent full text evaluation. Another 101 articles / sources of information were identified (and underwent full text evaluation) following searching the internet, hand searching of specialist palliative care textbooks, and hand searching of the reference lists of the included full text articles. Figure 2 gives an overview of the search of the literature.

Ten articles had a specific focus on palliative care and cancer survivorship [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]: five were commentaries [9, 10, 13, 15, 16], twowere literature reviews [11, 18], one was an editorial [14], one was a letter to the editor [12], and one involved original research (i.e. postal survey) [17]. Of note, six of these articles were published in oncology journals (three in oncology nursing journals) [10, 11, 13,14,15, 18], two in generic journals [9, 16], and only two in palliative care journals [12, 17].

A further eight articles concerned chronic pain in cancer survivors, and the actual / potential role of SPCTs in managing this cohort of patients [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Six of the remaining references were either generic cancer survivorship articles (that mentioned palliative care) [27,28,29,30,31], and four were generic palliative care articles (that mentioned cancer survivors / survivorship) [32,33,34,35]. Again, few of these articles were published in mainstream palliative care journals.

Literature review

Definition of “palliative care”

A number of definitions have been proposed for palliative care [36], although the most widely quoted ones are the older World Health Organization (WHO) definitions [37, 38], and the newer International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) definition (which evolved from the later WHO definition) [39]. The IAHPC define palliative care as “the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and their caregivers” [39]. The definition is supported by a series of additional characteristics, which include “is applicable throughout the course of an illness, according to the patient’s needs”, and “is provided in conjunction with disease-modifying therapies whenever needed” [39].

Definition of “specialist palliative care”

The European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) define three “levels” of palliative care: a) palliative care approach – “ applies to those with limited experience and knowledge in dealing with palliative care but can apply the basic principles of good palliative care”; b) generalist palliative care – “applies to those who are frequently involved with palliative care and have some specialist palliative care knowledge”; and c) specialist palliative care – “team members must be highly qualified and should have their main focus of work in palliative care” [40].

It is important to note that most palliative care is currently provided by generalists (e.g. general practitioners, oncology clinicians), rather than palliative care specialists due to resource constraints, and that this scenario is unlikely to change due to ongoing / increasing workforce challenges (i.e. recruitment, retention / natural turnover) [41], changes in population demographics (i.e. higher population, more aged population) [42], and improvements in oncology treatments / outcomes (resulting more patients living through cancer, and more patients living beyond cancer).

Current models of specialist palliative care

The “traditional” model of specialist palliative care focussed on patients with advanced cancer, and involved both symptom control and end-of-life care (Fig. 3) [32]. The “current” model of specialist palliative care reiterates the relevance of end-of-life care, but also highlights the importance of symptom control in other groups of patients with cancer (from the point of diagnosis) [32]. Moreover, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend that “patients with advanced cancer, whether inpatient or outpatient, should receive dedicated palliativecare services early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment” [43]. The latter is often referred to as “early” palliative care, and is endorsed by other national and international oncology organisations [44].

The current model of specialist palliative care is from the Lancet Oncology Commission on Integration of Oncology and Palliative Care [32]. As can be seen, the model does not address the issue of individuals living beyond cancer, and the Commission suggests that cancer survivorship (meaning living beyond cancer) falls under the remit of supportive care rather than palliative care. The latter is backed up by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC), who define supportive care as “the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment. This includes management of physical and psychological symptoms and side effects across the continuum of the cancer journey from diagnosis through treatment to post-treatment care. Supportive care aims to improve the quality of rehabilitation, secondary cancer prevention, survivorship, and end-of-life care” [45].

Supportive care has been used by some as a substitute for palliative care, with a major driver for this change being the widely held opinion that palliative care is synonymous with end-of-life care. However, although palliative care is an integral component of supportive care (as previously defined), supportive care is much more than palliative care, and requires input from a range of specialist teams and services [33]. Importantly, most SPCTs often have limited knowledge / experience of managing the active toxicities of anticancer treatments, and especially the newer immunotherapies and targeted treatments [34]. Furthermore, most SPCTs have even more limited knowledge / experience of managing the chronic toxicities of anticancer treatments, which has major implications for their involvement in the care of individuals living beyond cancer (see below).

Significantly, according to the NCI definition [2], all patients with a history of cancer are cancer survivors, including those with advanced / progressive disease, and even those in the final (terminal) stage of their illness. Thus, SPCTs already manage significant number of “cancer survivors”, although as previously indicated there is usually a clear demarcation between those subgroups that are routinely reviewed by these services, and those subgroups that are rarely (if ever) reviewed by these services (Table 2). Currently, SPCTs are seldom involved in the management of individuals living beyond cancer.

Core activities of specialist palliative care teams

SPCTs are extremely heterogenous in terms of their membership, services provided, and populations served [34]. Nevertheless, most SPCTs provide the core functions outlined in Box 1, although this range of services is usually restricted to patients with advanced cancer. As discussed, some SPCTs also provide early palliative care, some provide supportive care, and a smaller number also provide services for individuals living beyond cancer (generally symptom control).

Relevant expertise of specialist palliative care teams

The influential Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies report outlined four “essential components of survivorship care” [27]: 1) prevention of recurrent and new cancers, and of other late effects; 2) surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence, or second cancers; assessment of medical and psychosocial late effects; 3) intervention for consequences of cancer and its treatment, for example: medical problems such as lymphedema and sexual dysfunction; symptoms, including pain and fatigue; psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers; and concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability; and 4) coordination between specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met.

At first glance, there seem to be many synergies between the core activities of SPCTs, the essential components of survivorship care [27], and the well described unmet physical and psychosocial needs of individuals living beyond cancer (Table 1) [7, 46]. Unsurprisingly, there is some (limited) data to suggest support for the involvement of SPCTs in “long term cancer survivors” from oncologists, general practitioners, and oncology patients themselves [28]. Moreover, a number of oncology-related organisations have recommended involvement of SPCTs in the management of cancer survivors (and specifically the treatment of pain and related problems) [29, 30, 31]. However, there is less obvious support from palliative care-related organisations [47]. The reasons for the apparent reticence are discussed in the following section.

Many of the focused (palliative care and cancer survivorship) articles supported a palliative care approach to the management of individuals living beyond cancer, which is unsurprising since a palliative care approach is essentially a holistic approach (and is the basis for “good” healthcare irrespective of the cohort of patients) [9, 16]. However, some of the focused articles supported actual involvement of SPCTs, and this ranged from targeted interventions in specific cohorts (especially symptom control) [9, 11], to provision of more wide-ranging activities in those with unmet needs (e.g. advance care planning, coordination of care) [10, 13].

In terms of pain, SPCTs are adept in the treatment of acute / chronic cancer-related pain, and to a lesser extent acute cancer treatment-related pain. However, they are generally inexperienced in the treatment of chronic cancer treatment-related pain, which is a major problem in individuals living beyond cancer [48]. Moreover, the treatment of chronic cancer-treatment-related pain is fundamentally different to the treatment of acute / chronic cancer-related pain (especially in individuals with a limited prognosis) [31]. Thus, the neurophysiology is different, the efficacy of analgesics is often different (usually decreased), the risk / benefit of analgesics is often different (usually increased), and the focus of care is on improving patient function [19, 49]. Additionally, non-pharmacological interventions (e.g. physical exercise, psychological interventions) have a major role in the management of chronic pain, and these interventions are invariably provided by multidisciplinary chronic pain teams rather than SPCTs.

The same is equally true for the treatment of other physical symptoms, and to a lesser extent psychological symptoms. For instance, many of the chronic gastrointestinal problems caused by anticancer treatments require specialist investigations, and/or specialist interventions (which are outside the scope of practice of SPCTs) [50]: an example would be rectal bleeding from radiation-induced telangiectasia following pelvic radiotherapy. Similarly, SPCTs are not trained to deal with fear of cancer progression [9], which is a common problem amongst cancer survivors. Moreover, SPCTs do not tend to have experience in other “essential components of survivorship care” such as cancer surveillance, and cancer prevention [27], or the certain other unmet needs in this cohort of patients (e.g. financial toxicity, issues relating to employment) (Table 1) [7].

Importantly, there is currently a paucity of evidence to support the role of SPCTs in the management of patients living beyond cancer [18].

Potential barriers to change

There are a number of barriers to greater specialist palliative care involvement in individuals living beyond cancer (and similarly underserved groups of cancer survivors):

-

Limited resources

The National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care (NCHPC) in the USA contend that SPCTs do not have the capacity to see individuals living beyond cancer (“long-term cancer survivors”) as well as their usual cohorts of patients [47]. Moreover, this situation is likely to worsen due to changes in expected population demographics (resulting in greater numbers of patients, and smaller numbers of healthcare workers) [41]. However, the NCHPC suggest that SPCTs may be able to support dedicated cancer survivorship services in terms of education about the principles of palliative care, development of treatment algorithms, and potentially sharing relevant resources [47].

Importantly, any increase in service provision from SPCTs will require dedicated funding [13], and this will necessitate either provision of additional funding, or reallocation of current funding (which may have negative impacts on existing services). Moreover, this funding would need to be ongoing, and so necessarily supported by changes to healthcare policy / priorities at regional and national levels [18].

-

Lack of relevant expertise

As discussed, many of the problems encountered by individuals living beyond cancer are fundamentally different from those encountered in patients with advanced cancer (Table 1), and so SPCTs will need additional education / training if they are to provide the most suitable options for individuals living beyond cancer [35]. Indeed, extrapolating practice from patients with advanced cancer to individuals living beyond cancer is likely to lead to utilisation of ineffective interventions, and potentially to development of significant complications.

-

Nomenclature (“palliative care”)

The view that palliative care is synonymous with end-of-life care is commonplace amongst healthcare professionals, patients (including cancer survivors) [17], family carers, and the general population [13]. Indeed, such views have resulted in a reluctance from some oncology professionals (and other healthcare professionals) to refer patients with non-advanced cancer to SPCTs [51]. Thus, consideration will need to be given to improving understanding about palliative care, and/or rebranding of relevant services (e.g. “supportive and palliative care team”).

-

Lack of professional willingness

Many SPCTs have opted for a variety of reasons to solely manage patients with advanced cancer (and other life-limiting diseases), and have not engaged in developments such as early palliative care, and/or supportive care for cancer patients [34]. It is likely that the same would be true about providing services for individuals living beyond cancer.

Strengths / limitations

This review is unique in terms of its focus, and its strength relates to the methods utilised, whilst its weakness (limitations) relates to the current paucity of evidence regarding the involvement of specialist palliative care teams in the management of individuals living beyond cancer, i.e. small number of studies, limited quality of studies. Indeed, this paucity of evidence lends itself to performing a narrative review, rather than other types of review (e.g. scoping, systematic).

Conclusion

Individuals living beyond cancer have many unmet needs, and specific services are required to manage these problems. Moreover, a whole system, multidisciplinary, and inter-specialty approach is needed given the scale and breadth of these problems. Specialist palliative care teams could have a role to play, but this would require targeted education / training, and especially research to ensure that this input was effective and well tolerated (and did not disadvantage the usual cohort of palliative care patients).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Marzorati C, Riva S, Pravettoni G (2017) Who is a cancer survivor? A systematic review of published definitions. J Cancer Educ 32:228–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-0997-2

National Cancer Institute. Division of cancer control and population sciences. Office of cancer survivorship website: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/definitions. Accessed 30 Oct 2023

Oxford English Dictionary website: https://www.oed.com/. Accessed 30 Oct 2023

Cheung SY, Delfabbro P (2016) Are you a cancer survivor? A review on cancer identity. J Cancer Surviv 10:759–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0521-z

National coalition for cancer survivorship website:https://canceradvocacy.org/defining-cancer-survivorship/. Accessed 30 Oct 202

MD Anderson Cancer Center (2012) Survivorship. Living with, through and beyond cancer. MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX

Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez ED, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C, Sharma DK (2015) Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer 121:623–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28951

Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA (2008) Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 112(11 Suppl):2577–2592. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23448

Dy SM, Isenberg SR, Al Hamayel NA (2017) Palliative care for cancer survivors. Med Clin North Am 101:1181–1196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.06.009

Griffith KA, McGuire DB, Russo M (2010) Meeting survivors’ unmet needs: an integrated framework for survivor and palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 26:231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2010.08.004

Economou D (2014) Palliative care needs of cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 30:262–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2014.08.008

Rousseau PC (2014) Cancer survivorship and palliative care? J Palliat Med 17:984. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0159

Agar M, Luckett T, Phillips J (2015) Role of palliative care in survivorship. Cancer Forum 39:90–94

Kennedy Sheldon L (2017) The intersection of palliative care and survivorship. Clin J Oncol Nurs 21:11. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.cjon.11

Geerse OP, Lakin JR, Berendsen AJ, Alfano CM, Nekhlyudov L (2018) Cancer survivorship and palliative care: shared progress, challenges, and opportunities. Cancer 124:4435–4441. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31723

MacDonald C, Theurer JA, Doyle PC (2021) “Cured” but not “healed”: the application of principles of palliative care to cancer survivorship. Soc Sci Med 275:113802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113802

Stal J, Nelson MB, Mobley EM, Ochoa CY, Milam JE, Freyer DR, Miller KA (2022) Palliative care among adult cancer survivors: knowledge, attitudes, and correlates. Palliat Support Care 20:342–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1478951521000961

Morgan B, Kapadia V, Crawford L, Martin S, McCollom J (2023) Bridging the gap: Palliative care integration into survivorship care. Curr Probl Cancer 47:101019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2023.101019

Jennings C, Cassel B, Fletcher D, Wang A, Archer KJ, Skoro N, Yanni L, Del Fabbro E (2014) Response to pain management among patients with active cancer, no evidence of disease, or chronic nonmalignant pain in an outpatient palliative care clinic. J Palliat Med 17:990–994. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0593

Chwistek M, Ewerth N (2016) Opioids and chronic pain in cancer survivors: evolving practice for palliative care clinics. J Palliat Med 19:254. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0471

Zanartu C, Emond L, Wojtaszczyk A (2016) Survivor pain: experience at an oncology palliative care clinic. J Clin Oncol 34(26 Suppl):260. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.34.26_suppl.260

Goodlev ER, Discala S, Darnall BD, Hanson M, Petok A, Silverman M (2019) Managing cancer pain, monitoring for cancer recurrence, and mitigating risk of opioid use disorders: a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to cancer survivorship. J Palliat Med 22:1308–1317. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0171

Merlin JS, Patel K, Thompson N, Kapo J, Keefe F, Liebschutz J, Paice J, Somers T, Starrels J, Childers J, Schenker Y, Ritchie CS (2019) Managing chronic pain in cancer survivors prescribed long-term opioid therapy: a national survey of ambulatory palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 57:20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.493

Janah A, Bouhnik AD, Touzani R, Bendiane MK, Peretti-Watel P (2020) Underprescription of step III opioids in French cancer survivors with chronic pain: a call for integrated early palliative care in oncology. J Pain Symptom Manage 59:836–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.10.027

Check DK, Jones KF, Fish LJ, Dinan MA, Dunbar TK, Farley S, Ma J, Merlin JS, O’Regan A, Oeffinger KC (2023) Clinician perspectives on managing chronic pain after curative-intent cancer treatment. JCO Oncol Pract 19:e484–e491. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.22.00410

Jones KF, Wood Magee L, Fu MR, Bernacki R, Bulls H, Merlin J, McTernan M (2023) The contribution of cancer-specific psychosocial factors to the pain experience in cancer survivors. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 25:E85–E93. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000965

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Provencio M, Romero N, Tabernero J et al (2022) Future care for long-term cancer survivors: towards a new model. Clin Transl Oncol 24:350–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-021-02696-5

Cancer Control Joint Action (2017) European guide on quality improvement in comprehensive cancer control. National Institute of Public Health, Ljublijana and Scientific Institute of Public Health, Brussels

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2023) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Survivorship Version 1.2023. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Plymouth Meeting, PA. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/ Accessed 24 Mar 2023

Goyal N, Day A, Epstein J, Goodman J, Graboyes E, Jalisi S, Kiess AP, Ku JA, Miller MC, Panwar A, Patel VA, Sacco A, Sandulache V, Williams AM, Deschler D, Farwell DG, Nathan CA, Fakhry C, Agrawal N (2021) Head and neck cancer survivorship consensus statement from the American Head and Neck Society. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 7:70–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.702

Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, Campbell T, Cheville A, Citron M, Constine LS, Cooper A, Glare P, Keefe F, Koyyalagunta L, Levy M, Miaskowski C, Otis-Green S, Sloan P, Bruera E (2016) Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 34:3325–3345. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.68.5206

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M et al (2018) Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 19:e588–e653. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30415-7

Scotte F, Taylor A, Davies A (2023) Supportive care: the “keystone” of modern oncology practice. Cancers 15:3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153860

Gouldthorpe C, Power J, Taylor A, Davies A (2023) Specialist palliative care for patients with cancer: more than end-of-life care. Cancers 15:3551. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15143551

Power J, Gouldthorpe C, Davies A (2022) Palliative care in the era of novel oncological interventions: needs some “tweaking.” Support Care Cancer 30:5569–5570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07079-2

Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, Parsons HA, Kwon JH, Torres-Vigil I, Kim SH, Dev R, Hutchins R, Liem C, Kang DH, Bruera E (2013) Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 21:659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y

World Health Organization (1990) Cancer pain relief and palliative care. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2022) National Cancer Control Programmes. Policies and Managerial Guidelines, 2nd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F et al (2020) Redefining Palliative Care - a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:754–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027

Payne S, Harding A, Williams T, Ling J, Ostgathe C (2022) Revised recommendations on the standards and norms for palliative care in Europe from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC): a Delphi study. Palliat Med 36:680–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221074547

Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, Wolf SP, Shanafelt TD, Myers ER (2017) Future of the palliative care workforce: preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med 130:113–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046

Mills J, Ven S (2019) Future-proofing the palliative care workforce: why wait for the future? Prog Palliat Care 27:203–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699260.2019.1661214

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract 13:119–121. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2016.017897

Cherny NI, Catane R, Kosmidis P, ESMO Taskforce on Supportive and Palliative Care (2003) ESMO takes a stand on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 14:1335–1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdg379

Multinational association of supportive care in cancer website:https://mascc.org/. Accessed 30 Oct 2023

Firkins J, Hansen L, Driessnack M, Dieckmann N (2020) Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 14:504–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00869-9

National consensus project for quality palliative Care (2018) Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th edn. National coalition for hospice and palliative care, Richmond, VA

Snijders RAH, Brom L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ (2023) Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer 2022: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers 15:591. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030591

Brown M, Farquhar-Smith P (2017) Pain in cancer survivors; filling in the gaps. Br J Anaesth 119:723–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex202

Andreyev HJ, Davidson SE, Gillespie C, Allum WH, Swarbrick E, British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Colo-Proctology of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons; Faculty of Clinical Oncology Section of the Royal College of Radiologists (2012) Practice guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut 61:179–192. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300563

Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, Del Fabbro E, Swint K, Li Z, Poulter V, Bruera E (2009) Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 115:2013–2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24206

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium None of the authors received funding to produce this guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM and AD jointly conceived the project, reviewed the literature, and wrote the article (and agreed the final version).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Medline search strategy

-

1.

Cancer survivors MESH term

-

2.

Cancer survivorship key word

-

3.

Cancer survivor key word

-

4.

Living with cancer key word

-

5.

Living beyond cancer key word

-

6.

1 or 2–5

-

7.

Survivors MESH term

-

8.

Survivorship MESH term

-

9.

Survivor key word

-

10.

7 or 8–9

-

11.

Neoplasms MESH term

-

12.

Cancer key word

-

13.

11 or 12

-

14.

10 and 13

-

15.

6 or 14

-

16.

Palliative care MESH term

-

17.

Terminal care MESH term

-

18.

End of life care key word

-

19.

Hospice care MESH term

-

20.

16 or 17–19

-

21.

15 and 20

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, A., Davies, A. The role of specialist palliative care in individuals “living beyond cancer”: a narrative review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 32, 414 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08598-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08598-w