Abstract

Purpose

Almost 200,000 tongue cancers were diagnosed worldwide in 2020. The aim of this study was to describe occupational risk variation in this malignancy.

Methods

The data are based on the Nordic Occupational Cancer (NOCCA) study containing 14.9 million people from the Nordic countries with 9020 tongue cancers diagnosed during 1961–2005. The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of tongue cancer in each occupational category was calculated using national incidence rates as the reference.

Results

Among men, the incidence was statistically significantly elevated in waiters (SIR 4.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.13-–5.92), beverage workers (SIR 3.42, 95% CI 2.02-5.40), cooks and stewards (SIR 2.55, 95% CI 1.82-3.48), seamen (SIR 1.66, 95% CI 1.36-2.00), journalists (SIR 1.85, 95% CI 1.18-2.75), artistic workers (SIR 2.05, 95% CI 1.54-2.66), hairdressers (SIR 2.17, 95% CI 1.39-3.22), and economically inactive persons (SIR 1.57, 95% CI 1.42-1.73). Among women, the SIR was statistically significantly elevated only in waitresses (SIR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05-1.81). Statistically significant SIRs ≤ 0.63 were observed in male farmers, gardeners, forestry workers and teachers, and in female launderers.

Conclusions

These findings may be related to consumption of alcohol and tobacco, but the effect of carcinogenic exposure from work cannot be excluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A total of 378,000 new oral cancer cases (including the lip) were diagnosed worldwide in 2020, 264 000 among men and 114 000 among women [1]. Almost 50% of all oral cancer cases are located in the tongue, and more than 90% of them are squamous cell carcinomas [2, 3]. The 5-year relative survival of the tongue cancer patients diagnosed 2011–2020 in Finland was 64% in men and 75% in women [4]. The main risk factors for oral tongue cancer are smoking and alcohol consumption. Mucosal changes, such as erythroplakia and lichen planus may also increase the risk [5, 6].

The incidence of oral tongue cancer is on the rise among people < 45 years old worldwide, but the reason for the increase is unknown [7]. In the USA, the incidence of tongue cancer increased from 1973 to 2012 among people younger than 50 years, especially among women, although these birth cohorts did not smoke or use alcohol more than previous generations [8]. In the Nordic countries the incidence of tongue cancer has been rising among both sexes during the last decades [9]. Researchers have been trying to identify other risk factors, such as low consumption of fruit and vegetables [10], stress, oral hygiene, and family history [11].

The aim of this study, based on the data of the Nordic Occupational Cancer (NOCCA) project, was to determine the occupational risk variation in tongue cancer [12].

Materials and methods

The NOCCA cohort includes 14.9 million persons, born in 1896–1960, who participated in any computerized population census in 1960–1990 in the Nordic countries at the age of 30–64 years (2.0 million persons in Denmark, 3.4 million persons in Finland, 0.1 million persons in Iceland, 2.6 million persons in Norway, and 6.8 million persons in Sweden). All Nordic residents are given a personal identity code, and this was used to link data from the registries used in the study. Information on tongue cancer diagnoses (ICD-10 codes C01, C02) was based on the national cancer registries [12]. The follow-up started when the person entered the cohort and ended at emigration, death, or country-specific common closing date (end of year 2003 in Denmark and Norway, 2004 in Iceland, and 2005 in Finland and Sweden). Persons were classified based on the occupation recorded in the first census in which the person participated. The original occupational codes used in national census files were converted to 53 occupational categories and a category of economically inactive persons.

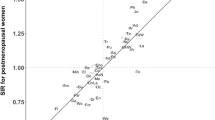

The relative level of tongue cancer incidence for an occupational category is described by the standardized incidence ratio (SIR), with the tongue cancer incidence rates for the entire national study populations used as reference rates. The analysis was stratified by country, sex, 5-year age groups, and 5-year calendar periods. For this study, the stratum-specific results were combined with broader categories of age (30–49, 50–69, 70+).

Results

Altogether 9020 new tongue cancer cases were diagnosed during the follow-up period (Table 1). Among men, statistically significantly elevated SIRs > 1.50 were found in waiters, beverage workers, cooks and stewards, seamen, journalists, artistic workers, hairdressers, and the economically inactive (Table 2). SIR was > 1.50 also among male dentists, but this finding was not statistically significant. Statistical significantly decreased SIRs < 0.67 were found among male farmers, gardeners, forestry workers, and teachers.

In women, the only statistically significant SIR (1.39, 95% CI 1.05–1.81) was observed among waitresses. Non-significant SIRs > 1.50 were found among dentists, printers, and artistic workers (Table 2). Low incidence with statistical significance was observed only among launderers (SIR 0.51, 95% CI 0.25–0.93).

Among male waiters, elevated SIRs were found in every age group, but the SIR decreased with age (Table 3). Among seamen, the excess decreased towards the older age groups, while the opposite was true for cooks and stewards, and dentists. Female printers had an elevated SIR (2.4, 95% CI 1.1–4.5) in the group 70 + years; this was the only statistically significant age-specific SIR among women.

Discussion

In this Nordic registry-based study, we compared the risk of tongue cancer in different occupations. In men, statistically significantly elevated SIRs were found among artistic workers, journalists, seamen, cooks and stewards, beverage workers, waiters, hairdressers, and the economically inactive. In women, only waitresses had a significant association with tongue cancer.

In waiters, the SIR was elevated in both sexes in every age group. Waiters may, more often than the population on average, have an irregular lifestyle, and they may need to work during the night. This can lead to unhealthy lifestyle choices, like unhealthy eating habits, excessive alcohol intake and smoking. Waiters use alcohol more than workers in other occupations. Among Swedish restaurant workers alcohol use was almost seven-fold in 2008–2009 [13], and among Norwegian waiters there were heavy drinkers almost three-fold in 1995 [14] compared to the average population. Waiters in the Nordic countries also smoke more than the average population [15, 16]. Waiters in pubs, bars and nightclubs have been heavily exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in the past [17, 18].

Male cooks and stewards had an elevated SIR, mainly in older ages. Cooks and stewards are exposed to cooking oil fumes during working hours. The cooks need to taste the food regularly, which leads to prolonged acid-attack and continuous mechanical irritation, and may further lead to caries and sharp spots that increase the risk of tongue cancer [19, 20]. It is possible that the elevated SIR seen among cooks and stewards aged 70 + years results from the cumulative exposure to prolonged acid attack and continuous mechanical irritation during the cooking career.

Incidence of tongue cancer was increased similarly in both sexes among dentists. The SIR for both sexes combined was 1.64 (95% CI 1.03–2.48). Among male dentists there was no excess of tongue cancer before the age of 70 years, but a highly elevated SIR in ages 70 + years, whereas among female dentists the SIR did not change with age. This finding suggests that – assuming that occupational ones are the same in both genders – there are non-occupational risk factors among male dentists which increase their risk of tongue cancer in higher ages. Hairdressers are regularly exposed to many chemical products, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified the exposure mixture in the hairdressing occupation as probably carcinogenic to humans based on elevated the risk cancers of the bladder and lung among hairdressers observed in previous studies [21]. In the present study, male hairdressers had an elevated at least two-fold SIR for tongue cancer in all age categories, but the SIR among female hairdressers decreased towards older age categories. The different findings between male and female hairdressers suggest that there may be other risk factors explaining the elevated SIRs.

In other occupational groups where the SIR was significantly elevated, we can only speculate the reasons. E.g., poor oral health [22, 23] or unhealthy diet, containing less fruit and vegetables [24], which are risk factors for oral cancer, could play a role in the etiology of tongue cancer, too, but we do not have occupation-specific information of such factors.

Strengths of this study include the large number of cancer cases during the follow-up and an accurate registration of tongue cancer diagnoses and occupational codes. However, because we do not have access to individual-level data on tongue cancer risk behavior factors, such as smoking or excessive alcohol consumption, we cannot estimate the role of these factors, factors likely to explain most of the excess risk in some occupational categories. Another limitation of this study is that only information on current occupation was recorded in the first available census instead of life-time occupational history. It has, however, been shown that occupational stability in Nordic countries is so high that the dilution of SIRs because of changes in occupation is relatively small [12].

Cancer located in the base of tongue has been registered as tongue cancer in the NOCCA database, and not as oropharyngeal cancer as it is classified nowadays. The fraction of cancers of the base of tongue in our data forms 10–20% of all cases. Like oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in general, base of tongue cancer is associated with human papillary virus 16 (HPV16) positivity [25,26,27], while cancer of the mobile tongue is not [28].

In conclusion, it seems that some work environments may include carcinogens that increase the risk of tongue cancer. On the other hand, there is variation between occupations in factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and unhealthy diet [24], which may also contribute to occupational variation in tongue cancer risk.

Data availability

The data shown in this article are based on the Nordic Occupational Cancer (NOCCA) project. According to the data permissions, data at an individual level had to be deleted after statistical analyses were done and results checked but can be reconstructed by repeating the same registry linkages with permissions of the original data sources. All tabulated data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, and partly (tabular data by country, sex, and occupation) also from the NOCCA website (https://astra.cancer.fi/NOCCA/).

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics, GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. 2021;71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Pires FR, Ramos AB, Oliveira JB, de Oliveira JB, Serra Tavares A, da Luz PS, dos Santos TC. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features from 346 cases from a single oral pathology service during an 8-year period. J Appl Oral Sci. 2013;21:460–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-775720130317.

Li R, Koch WM, Fakhry C, Gourin CG. Distinct epidemiologic characteristics of oral tongue cancer patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:792–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813477992.

Finnish Cancer Registry. Key statistics (Tongue, ICD-10: C02) https://syoparekisteri.fi/assets/themes/ssy3/factsheets/syopien-tietolaatikot/3en_Tongue.html, Accessed March 2024.

Ganesh D, Sreenivasan P, Öhman J, Wallström M, Braz-Silva PH, Giglio D, Kjeller G, Hasseus B. Potentially malignant oral disorders, and cancer transformation. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:3223–9. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12587.

Halonen P, Jakobsson M, Heikinheimo O, Riska A, Gissler M, Pukkala E. Cancer risk of Lichen planus: a cohort study of 13,100 women in Finland. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:18–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31025.

Ng JH, Iyer NG, Tan M-H, Edgren G. Changing epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: a global study. Head Neck. 2017;39:297–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24589.

Tota JE, Anderson WF, Coffey C, Califano J, Cozen W, Ferris RL, St John M, Cohen EEW, Chaturvedi AK. Rising incidence of oral tongue cancer among white men and women in the United States, 1973–2012. Oral Oncol. 2017;67:146–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.02.019.

Annertz K, Anderson H, Palmer K, Wennerberg J. The increase in incidence of cancer of the tongue in the nordic countries continues into the twenty-first century. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:552–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2011.649146.

Pavia M, Pileggi C, Nobile CGA, Italo F. Association between fruit and vegetable consumption and oral cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1126–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1126.

Dholam KP, Houksey GC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx in patients aged 18–45 years: a case-control study to evaluate the risk factors with emphasis on stress, diet, oral hygiene, and family history. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:244–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.197725.

Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Lynge E, Gunnarsdottir HK, Sparen P, Tryggvadottir L, Weiderpass E, Kjaerheim K. Occupation, and cancer – follow-up of 15 million people in five nordic countries. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:646–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860902913546.

Norström T, Sundin E, Müller D, Leifman H. Hazardous drinking among restaurant workers. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:591–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812456634.

Kjaerheim K, Mykletun R, Aasland OG, Haldorsen T, Andersen A. Heavy drinking in the restaurant business: the role of social modelling and structural factors of the workplace. Soc Study Addict. 1995;90:1487–95. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901114877.x.

Statistics Norway. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. http://www.ssb.no/en/helse/statistikker/royk/aar/. Accessed January 2023.

Statistics Sweden. Use of alcohol and tobacco pdf 2007. www.scb.se. Accessed January 2023.

Reijula JP, Reijula KE. The impact of Finnish tobacco legislation on restaurant workers’ exposure to tobacco smoke at work. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(7):724–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810379168.

Reijula J, Kjaerheim K, Lynge E, Martinsen J.E, Reijula K, Sparen P, Tryggvadottir L, Weiderpass E, Pukkala E. Cancer incidence among waiters: 45 years of follow-up in five nordic countries. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494814565130.

Singhvi HR, Malik A, Chaturvedi P. The role of chronic mucosal trauma in oral cancer: a review of literature. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5851.203510.

Bektas-Kayhan K, Karagoz G, Kesimli MC, Karadeniz AN, Meral R, Altun M, Unur M. Carcinoma of the tongue: a case-control study on etiologic factors and dental trauma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(5):2225–9. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.5.2225.

IARC monographs on the evaluation for carcinogenic risks. To humans - some aromatic amines, organic dyes, and related exposures. France: Lyon; 2010. pp. 499–658.

Homann N, Tillonen J, Rintamäki H, Salaspuro M, Lindqvist C, Meurman JH. Poor dental status increases acetaldehyde production from ethanol in saliva: a possible link to increased oral cancer risk among heavy drinkers. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(2):153–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00076-2.

Behnoud F, Torabian S, Zargaran M. Relationship between oral poor hygiene and broken teeth with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(3):159–62.

Helakorpi S, Paavola M, Prättälä R, Uutela A. Health behavior and health among Finnish adult population, Spring 2008. National Institute for Health and Welfare 2009, 1-185, http://www.thl.fi/avtk.

Sgaramella N, Coates PJ, Strindlund K, Loljung L, Colella G, Laurell G, et al. Expression of p16 in squamous cell carcinoma of the mobile tongue is independent of HPV infection despite presence of the HPV-receptor syndecan-1. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.207.

Dahlgren L, Dahlstrand H, Lindquist D, Högmo A, Björnestål L, Lindholm J, et al. Human papillomavirus is more common in base of tongue than in mobile tongue cancer and is a faorable prognostic factor in base of tongue cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1015–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20490.

Jouhi L, Halme E, Irjala H, Saarilahti K, Koivunen P, Pukkila M, Hagström J, Haglund C, Lindholm P, Hirvikoski P, Vaittinen S, Ellonen A, Tikanto J, Blomster H, Laranne J, Grenman R, Mäkitie A, Atula T. Epidemiological and treatment-related factors contribute to improved outcome of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Finland. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(4):541–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1400688.

Søland TM, Bjerkli I-H, Georgsen JB, Schreurs O, Jebsen P, Laurvik H, Sapkota D. High-risk human papilloma virus was not detected in a Norwegian cohort of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the mobile tongue. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2021;7(1):70–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.342.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet, and Selma and Maja-Lisa Selander`s Fund for Research in Odontology.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet, and Selma and Maja-Lisa Selander`s Fund for Research in Odontology.

Open Access funding provided by University of Helsinki (including Helsinki University Central Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P., T.S., and E.P. designed the study. J.I.M., E.L., E.P., L.T., K.K. and P.S. collected the data. J.P., R.N., A.A-S., A.M., T.S. and E.P wrote the main manuscript text and J.P. and E.P prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethnical approval and consent to participate

The data inspection boards and – where required – ethical committees in each of the Nordic countries approved the NOCCA study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclaimer Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Peltonen, J., Nikkilä, R., Al-Samadi, A. et al. Occupation and tongue cancer in Nordic countries. BMC Oral Health 24, 506 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04172-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04172-2