Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine whether allergic rhinitis is associated with periodontal disease in a representative sample of elderly Korean people that was adjusted for socio-demographic factors, oral and general health behaviors, and systemic health status.

Methods

A total of 10,643 subjects who were between 20 and 59 years of age participated in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and underwent cross-sectional examination. Medical history of allergic rhinitis was collected from participants by questionnaire; additionally, periodontal status was assessed using a Community Periodontal Index score of 3 or 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to adjust for socio-demographic variables, oral health status and behaviors, and general health status and behaviors. All analyses were performed using a complex sampling design.

Results

Allergic rhinitis and periodontitis showed a significant inverse association. After adjusting for all confounders, a trend of decreasing periodontitis risk was observed as allergic rhinitis increased. The adjusted odds ratio of periodontitis was 0.79 (0.66–0.95) for patients with allergic rhinitis.

Conclusion

A significant inverse association between allergic rhinitis and periodontal status was demonstrated in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Periodontal disease is a major bacterial infection that causes periodontal tissue destruction and bone resorption; it may result in tooth loss [1].

Chronic periodontal disease is reported in more than 90% of the American population [2]. In Korea, the prevalence of periodontal disease in adults over 19 years of age is 29.2%; furthermore, 3 out of 10 adults have periodontal disease that requires treatment, and the number of outpatients with periodontal disease continues to increase [3].

The most significant risk factor for periodontal disease is the composition of subgingival bacteria. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is considered to be a pathogen implicated in several forms of aggressive periodontitis, while Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tan-nerella forsythia are considered to be important etiological agents of chronic periodontitis [4]. In addition, age, sex, stress, socioeconomic status, systemic disease, inadequate host immune response, personal oral hygiene and smoking are factors that affect the development of periodontal disease [5].

Studies on the association between periodontal and systemic diseases have been recently reported [6, 7]. The most common systemic illnesses that are associated with periodontal disease include the following: diabetes mellitus, hyperglycemia, atherosclerosis, atheromatous disease, abnormal pregnancy, respiratory disease, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and cardiovascular disease [8]. In addition, studies have suggested that there is an association of between periodontal disease and allergic rhinitis [9].

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common allergic disease in which the nasal mucosa becomes hypersensitive to a variety of causative agents; it results in sinusitis, nasal congestion, otitis media, sleep disorders, and asthma [10]. AR is known to produce periodontal disease by causing chronic facial nasal obstruction and impaired breathing, leading to facial osteoarthritis, dental malocclusion, and dry mouth [11, 12].

On the other hand, the “hygiene hypothesis” suggests that infections in early infancy have preventive effects against the pathogenesis of allergies. Likewise, a low prevalence of periodontal disease has been reported in patients with allergic diseases [13].

Periodontal disease is a complex process in which pathogens interact with the host’s immune response; this process persists within the periodontal pockets and produces an acquired immune response that defends against microorganisms and pathogens [14]. Accordingly, the “hygiene hypothesis” posits that, in arthritic rhinitis and other immune diseases, exposure to various microorganisms activates and strengthens the immune system, thereby decreasing the incidence of periodontal disease. Studies investigating the association between allergic (e.g., rhinitis) and periodontal diseases are underway but are currently inadequate.

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the association between allergic rhinitis and periodontal disease by examining a representative sample of elderly Korean patients who were adjusted for socio-demographic factors, oral and general health behaviors, and systemic health status.

Methods

Study design and subject selection

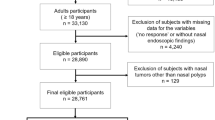

The data were derived from the Sixth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which was conducted by the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCP) from 2013 to 2015. The Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare performed the survey. The sampling protocol for the KNHANES was designed to employ a complex, stratified, multistage, and probability-based sampling design with proportional allocation in Korea. The KNHANES was approved by the institutional review board of the KCDC (2013-07CON-03-4C, 2013-12EXP-03-5C, and 2015–01-02-6C). The target population of the survey included all non-institutionalized civilian Korean individuals who were 1 year of age or older. The survey used stratified multistage probability sampling units that were based on geographic area, gender, and age; these sampling units were based on the households reported in the 2005 National Census Registry. The 2005 census data was used and 200 primary sampling units (PSU) were selected across Korea. The final sample for the KNHANES included 4600 households. In the KNHANES, physical and oral examinations, as well as blood sampling, were performed at mobile examination centers where trained staff members took all clinical measurements. The KNHANES included highly structured health-related questionnaires. Each participant signed an informed consent form during the survey. Previous publications of the KNHANES have described the sampling methods and survey contents in detail [15]. Out of the 22,948 participants of the KNHANES, only individuals who were between 20 and 59 years of age and had complete datasets were included in our analysis; consequently, we analyzed a total of 10,643 participants (4469 males and 6179 females) (Table 1). The following two exclusion criteria utilized: (1) participants who did not complete an oral examination and (2) subjects with one or more missing answers in their questionnaire.

Assessment of periodontitis

Trained dentists performed the oral health examination. The clinical examinations were performed with the subject seated in a dental chair while dentists utilized a light, mouth mirror, and World Health Organization (WHO) periodontal probe. The WHO community periodontal index (CPI) was used to assess the extent of periodontitis. According to the WHO guidelines, a CPI probe with a 0.5-mm ball tip was utilized with a probing force of approximately 20 g. Periodontitis was defined as a CPI greater than or equal to “code 3,” which indicates that at least one site had a pocket depth (PD) > 3.5 mm (“code 4” indicates a pocket > 5.5 mm). The index tooth numbers were 11, 16, 17, 26, 27, 31, 36, 37, 46 and 47 according to the Federation Dentaire Internationale (FDI) system. A sextant was examined only if two or more teeth were present that were not scheduled for extraction. If no index teeth were present in a sextant that was examined, all remaining teeth were probed and the highest score was recorded as the score for that sextant. The CPI was scored form 0 to 4 as follows: 0 (normal), 1 (gingivitis with bleeding on probing), 2 (presence of calculus), 3 (PD ≥ 3.5 mm) and 4 (PD ≥ 5.5 mm). The interexaminer reliability (mean of kappa value) was 0.84.

Assessment of allergic rhinitis

AR was defined according to patients’ self-reported answers to the question, “Has your doctor ever diagnosed you with AR?” Only patients who had received at least one AR diagnosis from a certified otolaryngologist were considered.

Assessment of potential confounders

We analyzed socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, household income, and education, as well as oral (e.g., tooth brushing frequency, prior history of periodontitis, dental visit within the past year, and the use of floss, interproximal brush, and mouthwash) and general health behaviors (e.g., smoking status and systemic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, asthma and atopic dermatitis). Socio-demographic, oral and general health behaviors were assessed by using the questionnaires in an interview format. General health-related factors were assessed using questionnaires, clinical examination and laboratory procedures. Monthly house hold income was categorized into quartiles and adjusted for the number of family members. Educational level was classified into the following four groups: primary school or less, middle school, high school and college. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, asthma and atopic dermatitis by were diagnosed by a physician. Obesity was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire survey. Dentists carefully assessed each patient’s periodontal status utilizing the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) to quantify the extent of periodontitis. The selected index tooth numbers were 11, 16, 17, 26, 27, 31, 36, 37, 46 and 47. The CPITN Index was scored from 0 to 4 as follows: 0 (normal), 1 (gingivitis with bleeding on probing), 2 (presence of calculus), 3 (pocket depth ≥ 3.5 mm) and 4 (pocket depth ≥ 5.5 mm). Periodontal status was grouped into the following two categories: absence (CPI of 1 to 2) and presence (CPI of 3 to 4) of periodontitis. The frequency of tooth brushing was divided into the following four groups: never, once daily, twice daily and more than three times daily. The use of floss, interproximal brush and mouthwash, as well as dental visits during the past year, were grouped into binomial yes or no categories.

Statistical analysis

The complex sampling design of the survey was utilized to obtain the variances and individual weight of each analyzed factor. To investigate the characteristics of AR and periodontitis patients, a chi-squared test of complex sample analysis with weight application was performed to estimate the weighted proportions (95% confidence interval [CI]) of the total sample population. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were sequentially applied to assess the association between AR and other variables after adjusting for age, sex, household income, education, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, asthma, atopic dermatitis, tooth brushing frequency, dental visit during the past year, and the use of floss, interproximal brush, and mouthwash.

A multiple logistic regression analysis of complex samples was carried out to evaluate the weight-adjusted association between AR and periodontitis. Model 1 represents a crude association. Model 2 is adjusted for sociodemographic factors. Model 3 is adjusted for all the variables in Model 2, including oral health status and behaviors. Model 4 is adjusted for all the variables in Model 3, including general health status and behaviors.

To enable the complex survey design involving stratified, random and cluster sampling, the SPSS Complex Samples Procedures were used for all statistical analyses (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21, IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

The characteristics of the study participants were categorized by AR. Of the 10,643 participants that were included in the analyses, 1640 (15.4%) had AR (Table 1). In our analysis, chi-squared tests were used to investigate the univariate association between confounding variables and AR. AR was more prevalent among younger participants, females, participants with higher education, and non-smokers. Among individuals with AR, asthma, atopic dermatitis, hypertension, obesity and periodontitis were observed to be more prevalent. Participants with AR were also observed to have greater tooth-brushing frequency and an increased use of both floss and interproximal brushes.

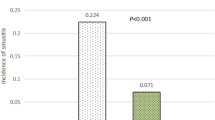

Association between periodontitis and potential confounding variables

The characteristics of the study subjects were categorized by periodontal status after controlling for all possible confounders (Table 2). The demographic characteristics of the participants were noteworthy for a higher percentage of males with periodontitis (30.5%) compared to females (18.7%); the odds ratio (OR) was 1.44 (95% CI: 1.27–1.63) for males with periodontitis. Periodontitis was present in 26.5% of the non-AR group and 15.8% of the AR group; the crude OR was 1.53 (95% CI: 1.28–1.82) for participants with both AR and periodontitis.

Association between AR and periodontitis

The associations between periodontitis and AR was analyzed using multivariable logistic regression models. These analyses revealed that the AR was inversely associated with the risk for periodontitis throughout the adjustment processes utilized in Models 1, 2, 3, and 4 (Table 3). After adjusting for socio-demographic factors, oral and general health behaviors, and general health factors, the inverse associations between AR and periodontitis remained significant.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that AR is inversely associated with periodontitis among Korean adults (aged 20–59 years) and that this association remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, household income, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, asthma, atopic dermatitis, periodontitis, tooth brushing frequency, dental visits during the past year, and the use of floss, interproximal brush, and mouthwash. These results were based on a national Korean population sample consisting of 10,643 participants and supported evidence from previous studies showing an inverse association between allergic disease and periodontitis [13]. To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence showing that AR is inversely associated with the prevalence of periodontitis in middle-aged adults.

We found that AR was more prevalent in women compared to men, which is similar to the results of another study conducted in the US [16]. Our results also showed that participants with lower age had a higher prevalence of AR; accordingly, Skoner reported that AR symptoms develop before the age of 20 years in approximately 80% of cases [17]. In addition, participants who had allergic diseases, such as asthma and atopic dermatitis, showed a higher prevalence of AR. Once a patient has become sensitized to allergens, subsequent exposures appears to trigger a cascade of events that result in AR symptoms [17].

There were a few studies on allergic disease and periodontitis in the literature. Friedrich et al. [13] conducted a study in a large Germany population sample to investigate whether allergic diseases such as hayfever, house dust mite allergy, and asthma were associated with periodontal disease; their study found that an inverse association between periodontitis and respiratory allergies. The present study, also showed an inverse association between periodontitis and allergic rhinitis as well as other allergic disease such as asthma and atopic dermatitis.

Several biological mechanisms have been suggested to explain how periodontopathic bacteria influence allergic rhinitis. Periodontal disease represents early infection, which may elicit an immune response, and the primitive conditions for the onset of periodontal disease may emerge in childhood [17]. Strachan [18] posited the “hygiene hypothesis,” which provides a potential explanation for the T-helper type 1 (Th1)/T-helper type 2 (Th2) paradigm [19, 20]. Allergic disease is Th2-mediated and characterized by the release of IgE; however, bacterial and viral infections are more likely to be Th1-mediated. Th2-derived cytokines inhibit the development of Th1 cells and vice versa. The infection-induced Th1-specific cytokine inhibits the development of allergen-specific Th2 cells. Several studies also supported the hygiene hypothesis [21, 22], suggesting that bacterial colonization elicit a systemic reaction that prevents the onset of allergic diseases.

Little is known about possible relationship between rhinitis and periodontitis. One study by Hung et al. has reported that rhinitis is associated with periodontitis, which is a finding that is different from the current study [9]. It should be noted that Hung et al. did not fully adjust for systemic factors. And another study by Choi et al. has also reported that asthma diagnosis is associated with tooth loss, however, this study focused on asthma not on allergic rhinitis [23].

There are four major strengths of our study. First, the KNHANES data utilized for this study was a large national survey that is representative of the Korean population. Seconds, professional examiners documented the general health examination and laboratory analyses. Third, trained dentists performed periodontal examinations and assessed oral health status. These results provide the first evidence linking periodontitis and AR among middle-aged adults. Finally, confounding factors showed a statistically significant independent association with periodontitis in our data, thus corroborating the reliability of our data.

This study has some limitations. Because the KNHANES is a cross-sectional survey, it is not possible to identify a causal relationship between AR and periodontitis; however, the biological plausibility of this association may indicate this relationship. Furthermore, the periodontal status was assessed using the CPI; therefore, the prevalence of periodontitis may have been overestimated or underestimated because the CPI’s use of representative teeth may include pseudo pockets [24]. Additionally, the method for defining AR was self-questionnaire, which runs the risk of recall bias, even if the question involves a physician’s diagnosis. Case control and cohort studies are needed to investigate the relationship between periodontal disease and AR.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results of our study are reliable enough to test the hypothesis that AR is inversely associated with periodontitis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found an inverse association between AR. Further case control and cohort studies are needed to confirm the hypothesis and mechanism of this inverse association between AR and periodontitis.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Allergic rhinitis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPI:

-

Community periodontal index

- CPITN:

-

Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs

- FDI:

-

Federation Dentaire Internationale

- KCDCP:

-

Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- KNHANES:

-

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PD:

-

Pocket depth

- PSU:

-

Primary sampling units

- Th1:

-

T-helper type 1

- Th2:

-

T-helper type 2

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Loesche WJ, Grossman NS. Periodontal disease as a specific, albeit chronic, infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:727–52.

Burt B. Position paper: epidemiology of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1406–19.

Choi YK, Do SR, Park DY. Change in number of outpatients with periodontal diseases during recent 20 years based on patient survey. J Kor Acad Oral Health. 2011;35:331–9.

Haffajee AD, Teles RP, Socransky SS. Association of Eubacterium nodatum and Treponema denticola with human periodontitis lesions. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:269–82.

Sweeting LA, Davis K, Cobb CM. Periodontal treatment protocol (PTP) for the general dental practice. J Dent Hyg. 2008;82:S16–26.

Tavares M, Lindefjeld Calabi KA, San Martin L. Systemic diseases and oral health. Dent Clin N Am. 2014;58:797–814.

Southerland JH, Gill DG, Gangula PR, Halpern LR, Cardona CY, Mouton CP. Dental management in patients with hypertension: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016;8:111–20.

Genco RJ, Williams RC. Periodontal disease and overall health: a Clinician’s guide. 2nd ed. Colgate-Palmolive Company: Pennsylvania; 2014.

Hung SH, Tsai MC, Lin HC, Chung SD. Allergic rhinitis is associated with periodontitis: a population-based study. J Periodontol. 2016;87:749–55.

Wu WF, Wan KS, Wang SJ, Yang W, Liu WL. Prevalence, severity, and time trends of allergic conditions in 6-to-7-year-old schoolchildren in Taipei. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:556–62.

Balyeat RM, Bowen R. Facial and dental deformities due to perennial nasal allergy in childhood. Int J Orthodont Dent Child. 1934;20:445–60.

Ebersole JL, Nagarajan R, Akers D, Miller CS. Targeted salivary biomarkers for discrimination of periodontal health and disease(s). Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015; https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2015.00062.

Friedrich N, Volzke H, Schwahnw C, Kramerz A, Junger M, Schaferz T, et al. Inverse association between periodontitis and respiratory allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:495–502.

Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: summary of developments clinical implication and future directions. Periodontol. 2000;14:216–48.

Korea Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Standardization for oral health survey in KNHANES (2014). Cheongwon-gun: Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. (Korean)

Nathan RA, Meltzer EO, Selner JC, Storms W. Prevalence of allergic rhinitis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:808–14.

Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2–8.

Bimstein E, Sapir S, Houri-Haddad Y, Dibart S, Van Dyke TE, Shapira L. The relation ship between porphyromonas gingivalis infection and local and systemic factors in children. J periodontal. 2004;75:1371–6.

Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1986;299:1259–60.

Romagnani S. Human TH1 and TH2 subsets: regulation of differentiation and role in protection and immunopathology. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;98:279–85.

Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH 1 and TH 2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;7:145–73.

Strachan DP. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the “hygiene hypothesis”. Thorax. 2000;55:S2–10.

Choi H, Bae KH, Lee JW. Association between age at asthma diagnosis and tooth loss. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;6:1–7.

Kingman A, Albandar JM. Methodological aspects of epidemiological studies of periodontal diseases. Periodontal. 2000;29:11–30.

Acknowledgements

This study was suppoprted by research fund from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017R1C1B5017185).

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study are owned KCDCP and were used under a confidentiality agreement to allow access to individual level data for the current study. Researchers can request the data from KCDCP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YKC designed the study, interpreted the data and revised the draft; EJK analyzed the data, wrote the draft, and English proof. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The data for the research was obtained from an existing database containing details of Korean National Nutritional and Health Survey from 2012 to 2015. The sixth KNHANES was a cross-sectional survey conducted by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCP) from 2012 to 2015. The KNHANES was approved by the KCDC Institutional Review Board (2013-07CON-03-4C, 2013-12EXP-03-5C, and 2015–01-02-6C).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, EJ., Choi, YK. Allergic rhinitis and periodontitis among Korean adults: results from a nationwide population-based study (2013–2015). BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 18, 12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12901-018-0062-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12901-018-0062-3