Abstract

Background

Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma (EES) is a rare malignant tumor primarily found in children and young adults. Localized disease can present with nonspecific symptoms such as local mass, regional pain, and increased skin temperature. More severe cases may present with systemic symptoms such as malaise, weakness, fever, anemia, and weight loss. Among these lesions, retroperitoneal sarcomas are relatively uncommon and difficult to diagnose. Since they are usually asymptomatic until large enough to compress or invade the surrounding tissues, most are already advanced at first detection. Traditionally, the treatment of choice is complete surgical resection, sometimes combined with postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy. We report a case of EES with left renal artery invasion in the left retroperitoneal cavity successfully treated with transarterial embolization and surgery.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old woman with a negative family history of cancer presented at our Urology Department with a large left retroperitoneal tumor found by magnetic resonance imaging during the health exam. Physical examination showed a soft abdomen and no palpable mass or tenderness. Imaging studies showed that the tumor covered the entire left renal pedicle, but the left kidney, left adrenal gland, and pancreas appeared tumor free. Since the tumor tightly covered the entire renal pedicle, tumor excision with radical nephrectomy was advised. The patient underwent transarterial embolization of the left renal artery with 10 mg of Gelfoam pieces daily before surgical excision. Tumor excision and left radical nephrectomy were uneventful the day after embolization. Post-operatively, the patient recovered well and was discharged on day 10. The final histopathological analysis showed a round blue cell tumor consistent with an Ewing sarcoma, and the surgical margins were tumor free.

Conclusions

Retroperitoneal malignancies are rare but usually severe conditions. Our case report showed that retroperitoneal EES with renal artery invasion could be treated safely with transarterial embolization and surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ewing’s sarcoma (ES) is a rare malignant tumor composed of small round cells, which Ewing first described in 1921 [1]. ESs have been reported throughout the human body. They can be classified as ES of the bone, extraskeletal ES (EES), malignant small cell tumors of the chest wall (Askin tumor), and soft tissue-based primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET) [2, 3]. EESs most often occur in soft tissues in the paravertebral region, chest, extremities, and retroperitoneal [4]. Most cases involve children, adolescents, and young adults, with > 90% of cases having disease onset between the ages of four and 25 [5]. Local masses, localized regional pain with variable intensity, increased skin temperature, and restricted limb movement due to nerve invasion are common [6]. Systemic symptoms such as malaise, weakness, fever, anemia, and weight loss may occur in metastasis disease [4]. Unfortunately, these symptoms are nonspecific and cannot distinguish EES from other tumors. Traditionally, treatment of choice is complete surgical resection, sometimes combined with postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy [7, 8]. Even after complete therapy, patients with EES have poor prognoses and high metastasis or recurrence risks [9].

Retroperitoneal sarcoma is relatively uncommon, accounting for < 15% of all soft tissue sarcomas [10]. They are usually asymptomatic until large enough to compress or invade the surrounding tissues. Since patients often come to medical attention with an incidentally observed mass lesion found during a health exam or image studies for other reasons, most tumors are already advanced at first detection [11]. Patients with high-grade, rapidly expanding tumors may present with fevers and leukocytosis. Laboratory examinations are usually uninformative in diagnosing these tumors [12]. Radiographic imaging is a key component of evaluating patients with retroperitoneal tumors. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is often the preferred tool for detecting the primary retroperitoneal lesion [13]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium is an alternative for patients with allergies to iodinated contrast agents. It is superior for delineating the tumor’s extension into the surrounding tissues [14]. Due to their nonspecific clinical characteristics, retroperitoneal EESs often have delayed diagnosis and treatment. Here, we report a case of EES with left renal artery invasion in the left retroperitoneal cavity successfully treated with transarterial embolization and surgery.

Case presentation

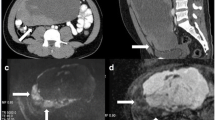

A 57-year-old woman with a negative family history of cancer presented at our Urology Department with a large left retroperitoneal tumor found by MRI during the health exam (Fig. 1). Physical examination showed a soft abdomen and no palpable mass or tenderness. An abdominal CT scan showed an 8.3 × 8.5 × 6.8 cm heterogeneous tumor in the left para-aortic region with a mass effect on the left kidney (Fig. 2A). Imaging studies showed the tumor covered the entire left renal pedicle, but the left kidney, left adrenal gland, and pancreas appeared free of tumor. The tentative diagnosis was retroperitoneal sarcoma or liposarcoma. Therefore, surgical excision was indicated.

The patient consented to an exploratory laparotomy with tumor resection and left radical nephrectomy. Since the tumor tightly covered the entire renal pedicle (Fig. 2B-C), tumor excision with radical nephrectomy was advised. Consider renal artery control and ligation prior to ligation of the renal veins may not be feasible in this special case. Besides, significant collateral feeding vessels to this perivascular tumor might hamper the pedicle control and very likely increase risk of intraoperative bleeding. To reduce the bleeding risk and possible intra-operative complications, the patient received a single transarterial embolization of the left renal artery with 10 mg of Gelfoam pieces daily before surgical excision (Fig. 3). The operation began with a midline incision, and exploration revealed a larger retroperitoneal mass invading the left renal pedicle that was tightly adhered and could not be separated. No direct aortic invasion was noted after careful tumor and aorta dissection. Since the left renal artery had been embolized, proper pedicle control was easily achieved with suture ligation. The entire tumor could be easily removed with adequate control of its blood supply. There was some adhesion between the tumor and the psoas muscle, which was negative for malignancy. Hemostasis was maintained, and the abdomen and skin were closed in the usual manner.

Post-operatively, the patient recovered well and was discharged on day 10. The final histopathological analysis showed a round blue cell tumor consistent with ES/PNET (Fig. 4). Fortunately, the surgical margins were tumor free, so the resection was considered complete. Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy were to be performed later by an oncologist.

The postoperative follow-up showed that the patient recovered well. The most recent clinic follow-up so far was 6 months after the operation, and the imaging studies showed no tumor recurrence. During this period, the patient has received complete radiation therapy (44 Gy/22fx, tumor bed and left kidney region) and is receiving chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide). No serious adverse effects other than mild leukopenia. The patient is still under follow-up and treatment in our hospital.

Discussion and conclusions

Most retroperitoneal tumors are malignant and account for one-third of soft tissue sarcomas. They usually present as large masses at primary diagnosis. Patients will be asymptomatic until the mass is large enough to compress or invade contagious structures. Patients may have nonspecific abdominal symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, distention, nausea, and vomiting [15, 16]. The family of ES and related tumors is characterized by small round blue cell tumors associated with a nonrandom t(11:22)(q24:q12) chromosome rearrangement [4, 17]. ESs and PNETs are well-known tumors in this family. They are malignant small blue round cell tumors with variable degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation [18]. Since the most common site of ES is the bone, most pediatric patients have so-called skeletal ESs, while ESS is very rare. Unlike children, more than 50% of ESs in adults are ESS, which can develop in the trunk, intraabdominal tissues, retroperitoneum, and viscera [18,19,20]. These tumors often present with rapid growth and widespread metastasis, leading to poor prognoses [21].

Imaging studies are essential for diagnosing such retroperitoneal lesions. MRI is the preferred tool for delineating the tumor’s extent and relationship with adjacent tissues or blood supplies [16]. However, while imaging studies are necessary, they cannot make a definite diagnosis due to other equivalent tumors having the same imaging characteristics [18]. Tissue confirmation of such tumors is always required. Specific stains are helpful for diagnosis, including those for the CD99 molecule (Xg blood group), micrometastases, vimentin, nonspecific esterase, S100 calcium-binding proteins, desmin, and cytokeratins [20,21,22,23]. Multimodal treatment consisting of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and high-dose radiotherapy (if indicated) has been recommended [24]. Prognostic factors are similar for ESS and ES, such as the presence or absence of metastasis, tumor size, extent of necrosis, and response to chemotherapy [25]. The quality of the primary excision is also important for local and distant recurrence, and wider resection margins are required [26]. Furthermore, combining surgery with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy is recommended based on the location, respectability, and tumor stage [27]. The patients should undergo radiotherapy when negative surgical margins cannot be achieved [8]. In patients with distant metastasis, chemotherapy remains an option after primary tumor excision, providing better progression-free survival [28]. In some reports, targeted therapy and immunotherapy also play a role in ES treatment [29, 30]. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of ESS presenting with renal artery invasion but a normal kidney. In our case, the patient had nonmetastatic disease. She received a tumor resection with negative surgical margins after renal artery embolization. She underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy to avoid local and distant metastasis. Continuous follow-up is necessary for treatment outcome evaluations.

In conclusion, retroperitoneal malignancies are rare but usually severe conditions. Their clinical symptoms are usually nonspecific. Imaging studies are required for primary diagnosis, but a definite diagnosis still depends on histopathology. EES is one of the differential diagnoses of retroperitoneal malignancy, characterized by small blue round cells. Multimodality treatment comprising surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy is recommended for better outcomes. Our case report shows that retroperitoneal EESs with renal artery invasion can be treated safely with transarterial embolization and surgery.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ES:

-

Ewing’s sarcoma

- EES:

-

Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma

- PNET:

-

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Ewing J. The Classic: Diffuse endothelioma of bone. Proceedings of the New York Pathological Society. 1921;12:17. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:25–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000229311.36007.c7.

Murphey MD, Senchak LT, Mambalam PK, Logie CI, Klassen-Fischer MK, Kransdorf MJ. From the radiologic pathology archives: ewing sarcoma family of tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):803–31. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.333135005.

Arpaci E, Yetisyigit T, Seker M, Uncu D, Uyeturk U, Oksuzoglu B, Demirci U, Coskun U, Kucukoner M, Isıkdogan A, Inanc M, Alkis N, Ozkan M. Prognostic factors and clinical outcome of patients with Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors in adults: multicentric study of the Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-013-0469-z.

Iwamoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(2):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyl142.

Muralidhar D, Vasugi GA, Sundaram S. Incidence and demographic Profile of Ewings Sarcoma: experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18339. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18339. Published 2021 Sep 28.

Riggi N, Suvà ML, Stamenkovic I. Ewing’s Sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):154–64. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2028910.

Grünewald TGP, Cidre-Aranaz F, Surdez D et al. Ewing sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):5. Published 2018 Jul 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0003-x.

Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, et al. Ewing Sarcoma: current management and future approaches through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(27):3036–46. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5256.

Xie CF, Liu MZ, Xi M. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma: a report of 18 cases and literature review. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(4):420–4. https://doi.org/10.5732/cjc.009.10402.

Raut CP, Pisters PW. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: combined-modality treatment approaches. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94(1):81–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20543.

Stoeckle E, Coindre JM, Bonvalot S, et al. Prognostic factors in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a multivariate analysis of a series of 165 patients of the French Cancer Center Federation Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2001;92(2):359–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2<359::aid-cncr1331>3.0.co;2-y.

Storm FK, Mahvi DM. Diagnosis and management of retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 1991;214(1):2–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199107000-00002.

Messiou C, Moskovic E, Vanel D, et al. Primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: imaging appearances, pitfalls and diagnostic algorithm. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(7):1191–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.10.032.

Panicek DM, Gatsonis C, Rosenthal DI, et al. CT and MR imaging in the local staging of primary malignant musculoskeletal neoplasms: report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1997;202(1):237–46. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.202.1.8988217.

Harimaya K, Oda Y, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Chuman H, Iwamoto Y. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor and extraskeletal ewing sarcoma arising primarily around the spinal column: report of four cases and a review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(19):E408–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000085099.47800.DF.

Wright A, Desai M, Bolan CW, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma from Head to Toe. Multimodality Imaging Review Radiographics. 2022;42(4):1145–60. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.210226.

Burchill SA. Ewing’s sarcoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications of molecular abnormalities. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(2):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.56.2.96.

Ulusan S, Koc Z, Canpolat ET, Colakoglu T. Radiological findings of primary retroperitoneal ewing sarcoma. Acta Radiol. 2007;48(7):814–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841850701408244.

Ozaki Y, Miura Y, Koganemaru S et al. Ewing sarcoma of the liver with multilocular cystic mass formation: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:16. Published 2015 Jan 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1017-3.

Nedham FN, Nagaraj V, Darwish A, Al-Abbasi TA. Retroperitoneal blue cell round tumor (ewing sarcoma in a 35 years old male)- case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107045.

Javalgi AP, Karigoudar MH, Palur K. Blue Cell Tumour at Unusual Site: Retropritoneal Ewings Sarcoma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(4):ED19–ED20. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/18302.7618.

Akhtar M, Ali MA, Sabbah R, Bakry M, Nash JE. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of round cell malignant tumors of childhood. A combined light and electron microscopic approach. Cancer. 1985;55(8):1805–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19850415)55:8<1805::aid-cncr2820550828>3.0.co;2-6.

Layfield LJ, Glasgow B, Ostrzega N, Reynolds CP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology and the diagnosis of neoplasms in the pediatric age group. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7(5):451–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.2840070504.

Tural D, Molinas Mandel N, Dervisoglu S, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors in adults: prognostic factors and clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(5):420–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hys027.

Lee WS, Kim YH, Chee HK, et al. Multimodal treatment of primary extraskeletal ewing’s sarcoma of the chest wall: report of 2 cases. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41(2):108–12. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2009.41.2.108.

Casali PG, Bielack S, Abecassis N, et al. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv79–iv95. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy310.

Castex MP, Rubie H, Stevens MC, et al. Extraosseous localized ewing tumors: improved outcome with anthracyclines–the french society of pediatric oncology and international society of pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(10):1176–82. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0559.

Galyfos G, Karantzikos GA, Kavouras N, Sianou A, Palogos K, Filis K. Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma: diagnosis, prognosis and Optimal Management. Indian J Surg. 2016;78(1):49–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-015-1399-0.

Italiano A, Mir O, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced ewing sarcoma or osteosarcoma (CABONE): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):446–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30825-3.

Morales E, Olson M, Iglesias F, Dahiya S, Luetkens T, Atanackovic D. Role of immunotherapy in ewing sarcoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000653. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-000653.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (TCMF-JCT-112-11) and Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (TCRD-TPE-112-12 and TCRD-TPE-110-12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, YC Tsai; methodology, SY Wu and YC Tsai; investigation, SY Wu, CK Hsu and CT Yue; writing—original draft, SY Wu and CK Hsu; writing—review and editing, YC Tsai. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The photographs are completely unidentified and personal details are not mentioned in the text. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Patient consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, SY., Hsu, CK., Yue, CT. et al. Large retroperitoneal extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma with renal pedicle invasion: a case report. BMC Urol 23, 95 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-023-01272-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-023-01272-z